Why do we Leave it so Late? Response to Environmental Threat and the Rules of Place

Received: 09-Aug-2013 / Accepted Date: 17-Oct-2013 / Published Date: 24-Oct-2013 DOI: 10.4172/2157-7617.1000169

Abstract

It is generally accepted that human behaviour needs to change if the depredations of climate change are to be reduced. Yet despite overwhelming evidence for this need there has been remarkably little modification of what people do. This paper introduces the environmental science community to the general area of environmental psychology. It argues that there is a need to look beyond scientific facts about the environment if human environmental activity is to change. This essay looks for roots of our present understanding of human interactions with the environment in the early Romantic Movement rather than scientific discoveries. Behaviour in disasters and emergencies is also considered to explain the fundamental psychosocial reasons why human activity will not change until there are incontrovertible experiences that demonstrate that the social rules that shape how we interact with our surroundings (‘rules of place’) must be changed. The argument draws on a literature not usually considered by those concerned with climate change to indicate why it is that people carry on with their quotidian actions until it is clear they can no longer be sustained.This reflects a common human tendency to leave it too late to act in the face of growing threats. Implications of this perspective are discussed.

Keywords: Climate change; Emergencies; Place rules; Human actions

5555Introduction

Why, given what is known about global warming, given all the environmental changes that are so obviously going on, why are people not reacting to them much more effectively and quickly? As Sunstein [1] points out the US has responded more effectively to the threat of terrorism than to climate change. The reason Sunstein gives, as do others [2], is that human cognitive processes are limited in appreciating the real significance of climate change and that; in essence, more information is needed to convince people of the necessity of modifying their activities.

The present essay reviews a range of studies that reveal the processes that shape how people interact with their surroundings. It draws on the results of these studies to argue that the emphasis on cognitive processes, as valuable as that is, fails to take account of the social-psychological processes that hold back human actions in the face of change. It is argued that an understanding of how people make sense of and use their surroundings indicates crucial limits to what people are prepared to change in regard to their use of their environment. In particular studies of behaviour in life-threatening situations [3,4] demonstrate how wedded people are to their daily activities. It will be shown that actions in place are not some superficial aspect of a person but are integral to individuals’ self-concept. The person we think we are is shaped by the patterns of place use we participate in [5].

Much of the research exploring the meanings and use of places was initially carried out in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Although there has been a continuing development of those earlier explorations [6,7]. However, the significance of these studies has been somewhat masked by the development of biological and physical considerations of environmental change. Currently, the growing concerns with the lack of response to environmental threats are bringing these issues back into consideration [5].

These patterns of place use and meaning can be understood as an aspect of what have been called ‘rules of place’ [8]. It is these set of expectations and social norms that both a) enable people to make effective use of their surroundings and also b) shape how those surroundings are used. But these place rules are so embedded in how people act that it is extremely difficult to change them. The argument is that reactions to threatening circumstances are left so late because of the psychological discomfort that is caused by changing the way we interact with our surroundings [9].

The argument here is that the processes that introduce inertia into reactions to environmental change, and limit variations in behaviour so that it is not modified to reduce environmental threats are fundamentally social psychological processes. These are the same processes that have led to many emergencies in the past getting out of control to become disasters, despite clear early warnings of imminent danger [3]. These ways of relating to each other, and the habits of where we do what, underpin the slowness to respond to the demands of climate change.

Social Psychological Processes

Discussions about human dealings with the environment rarely focus on the psychological issues behind personal decisions and actions. It is unusual for the actual understandings, actions and experiences of individuals in dealing with their physical surroundings to be part of the environmental debate. Broad swath topics in the realm of economics, such as carbon trading, political events, wide ranging policy considerations and debates about new technologies dominate discussions. Clearly these explore important issues, but it is unusual for the decisions and actions of individuals going about their daily lives to be considered directly. People are dealt with as pawns to be manipulated by economic and political forces, not as sentient agents interacting consciously with their environment. It is further assumed that broad political changes, such as more effective and reliable public transport will inevitably and automatically lead to changes in what people do. Yet these policy debates leave out careful consideration of how people actually act on their world and the social and psychological processes that sustain those actions.

The key to understanding human interactions with the physical surroundings is to recognise one fundamental aspect of the evolutionary process that is too often ignored. Curiously it was Count Kropotkin (1842-1921), one of the leading thinkers amongst 19th century Anarchists, who emphasised that in order for species to survive and to mate, they have actually got to be together. Therefore, there is always a need within any evolutionary context for animals to interact effectively. There is always a social process in any animal group. For human beings this is mediated by language and self-conscious cognition. It is fundamental to human survival that humans have some understanding of each other and can work together in ways that are more productive than destructive. This requires a shared set of conceptualisations, especially in the use of their surroundings.

A further point that can be drawn from an understanding of the evolutionary imperative is that evolution unfolds, and organisms survive in their environment, because of local, small scale transactions. There may be global changes that create local conditions, but it is their impact at the level of individuals going about their daily activities that produces their effects. If a micro-climate manages to avoid the global pattern then actions and organisms in that location will not be effected. It is necessary to consider what it is that maintains activity in any given setting in order to understand why people leave it so late to deal with environmental threats.

The Origins of the Environmental Movement

A further understanding of how local processes, relating to interactions between individuals, is the key to environmental change can be gleaned from a consideration of the roots of present day concerns with the use and abuse of the environment. It is not usually appreciated, as Cronon [2] indicates, that the environmental movement and concerns with global changes can be traced to roots in the early Romantic Movement and the Romantic poets. This predates Darwin’s Origin of Species by almost 100 years. It is an intriguing aside to note that it is often poets, novelists and playwrights who identify crucial issues and draw attention to them before scientists eventually turn them into something more mundane and technical, often losing some of the emotional power of the poet’s insight. This may be one of the messages for those who seek to have climate change taken more seriously, perhaps what is in the debate is more drama and poetry that deals with localised, individual experiences and fewer facts and figures?

Looking back to what is often regarded as the origins of concerns with the environment there are some remarkable parallels to present day discussions. Oliver Goldsmith’s (1730-1774) poem The Deserted Village, published in 1770 is regarded by many as the starting point for the development of a Romantic attachment to the natural, rural landscape and a notional Golden Age in which humanity all lived in a pleasant, Arcadian environment. The essence of the poem is captured in the stanza

Sweet, smiling village! Loveliest of the lawn

Thy sports are fled, and all thy charms withdrawn:

Amidst thy bowers the tyrant’s hand is seen,

And desolation saddens all thy green;

He is bemoaning the fact that this idyllic village, Auburn, in which he grew up is now empty. The people have left the countryside to go into the nasty town. The trend, started most clearly with the British industrial revolution, is today mirrored across the globe, with peasant, village life fading as cities develop rapidly with vast numbers of individuals coming in from the countryside. And who is causing the problem? The tyrants, the rich multi-nationals; the organisations that are making it more attractive to go into the town.

Although the Deserted Village is apparently about the loss of a rural idyll and the degradation caused by urbanisation it is more fundamentally an exploration of the breakdown of the relationship between people and their physical environment. It is an early recognition that countryside is not just a resource to be exploited but an integrated part of who we are and how we live.

In many senses the poem heralds a new humility in which the domination of nature by humanity is no longer the unchallenged norm. It is a budding flower of the Romanticism, given such impetus by Wordsworth and Coleridge, in which people are seen as part of nature rather than its inevitable masters. The Romantic vision that perfection resides in the everyday, rather than in some aspirational ideal, puts human beings on a par with nature rather than being above it. It is then a small step to recognise that we are all an integral part of the natural world, so that what we do to nature influences who we are.

Such lack of arrogance also leads to the implication that if people are all part of the natural order then there is no fundamental difference between one person and another. There should be no surprise therefore that the Lakeland poets were so enamoured of the French Revolution, which was rooted so clearly in equality. Nor should the route from Goldsmith’s Deserted Village to broad political movements be unexpected.

It is not often appreciated that the philosophy behind both Romanticism and the destruction of the Ancient Regime cleared the ground for the theory of evolution. Once it was acceptable to think of humanity as part of nature and all human beings as equal, eventually someone would have seen the implication that it meant people and animals had similar origins. The further ecological implications took longer to emerge, but the idea that we owe our survival as a species to how we interact with our environment has some of its origins in concerns for the consequences of leaving villages for the depredations of the town.

Also fascinating about Goldsmith’s poem are two aspects to it that tell us a lot about our relationship with the environment. One is that Goldsmith never returned to Auburn, spending his life in London. The conditions that he so bemoans were so pervasive and the attractions of the city so seductive that he himself never felt the need or possibility of returning to the village, other than to research his poem. This tells us how difficult it is to change our patterns of activity despite our ideology. Another important insight in the poem is that what Goldsmith sees as so wonderful about Auburn, now lost forever, are all the different places and their associated activities that took place there. For example, the village school, so dominated by its schoolmaster:

And still they gazed, and still the wonder grew,

That one small head could carry all he knew.

Whose many jokes had to be laughed at, funny or not:

Full well they laugh'd with counterfeited glee

At all his jokes, for many a joke had he;

It talks about the vicarage. It talks about the local pub. In other words, what Goldsmith is drawing attention to is not an attractive, picturesque countryside. It is not an area in which you can admire the beauty of nature. It is the opportunity for certain sorts of activities in small groups, with people relating to each other; being part and parcel of a community that is not being broken apart in the way that he sees the city breaking the community apart.

So the Romantic image of nature is of the opportunities it gives us to experience ourselves and interactions with others that have an untrammelled quality. This draws attention to the uses of places and to the ways in which there are benefits from being able to operate within a particular physical context. It is not an exploration of the scenic that looks on the natural environment as an object to enjoy from afar, but as a milieu which helps to define the nature of human existence.

The Emergence of Environmental Psychology

The Romantic tradition eventually found its way into the Social Sciences, most notably in the 1960’s. In the US and the UK there developed systematic studies of people’s experiences of the environment. Initially it was called Architectural Psychology [10] but its earliest origins were based not in reference to buildings but looking at what people actually did day to day. Indeed the first major study just examined what one boy did throughout his day [11]. This was then extended to consider children more broadly within one small town [12].

The Romantic fundamentals to this painstaking examination of what children actually do and experience only becomes apparent when it is appreciated that the whole focus of the studies were on one small town in the mid-West of America. Furthermore, Barker and his colleagues [13] who carried out these studies actually moved to the town they were studying, Oskaloosa, Kansas, in order to do their research there, happily spending their whole lives there. Underlying their exceptionally detailed observations is an obvious delight in what this very small town had to offer. This ideology eventually became clearer in later work which implicitly promulgated the idea of ‘small is beautiful’ [14] long before it became a slogan. They argued that the opportunities for personal development were richer in a small community.

The essence of what Barker and his colleagues called Ecological Psychology [13] was founded on their idea of a ‘behavioural setting’. This was described as a recurring pattern of activity that had a particular time and place. In their study of Oskaloosa, the drug-store was one such setting that they looked at closely. In their studies of schools it may be a grade 10 French lesson, or the school band rehearsal. The important point was that our lives are made up of these settings. Indeed the point was made quite strongly that if you want to predict how a person will act, knowing the setting they are in will be much more useful than knowing anything about their personality.

The Importance of Human Agency

A crucial criticism of Ecological Psychology was that it seemed to assume a remarkably determinist model of human transactions with the surroundings. The agency of the individual was greatly undervalued. This was probably a result of a Barker’s intellectual roots in the behaviourist tradition, following the theories of B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) who claimed that it was the patterns of reward and punishment (‘reinforcements’) that shaped human (and animal) actions. Barker’s studies in the Oskaloosa where originally aimed at finding what patterns of reinforcement children actually experienced.

However, many people argued that human agency plays a significant role in all our dealings with the world. Consequently, in the 1960’s, in what became known as Environmental Psychology, [15] there was a lively debate between a highly determinist view of the influence of the surroundings and the perspective that gave emphasis to what people bring to any setting. This is crucial to explore in the context of environmental policy making. Will how people respond to climate change be modified by adjusting the ‘reinforcements’ they experience, such as the negative reinforcement of punitive prices for petrol, or the positive inducement of bicycle paths? Or do we need to engage more directly with how people think of themselves and the sort of people they think they are and their active choices?

One consequence of human agency, revealed in a variety of studies [15] conducted in settings as various as hospitals, schools, offices and public parks is that the physical environment does not have any direct, immediate impact on human activity, provided the environment is within the bounds of tolerance, for heating, lighting, acoustics and space. There are many examples of very effective activities being carried out under what many would regard as appalling conditions. Similarly there are plenty of ultra-efficient environments that do not seem to have given rise to happy or productive workforces. The effects of the environment are indirect, through processes such as who chooses to be there and what they intend to do when they get there and the various symbolic qualities that support those intentions and activities.

Nonetheless, what a person expects of a place and intends to do there is to a marked degree influenced by what goes on in that location. Therefore the insights of Barker and his colleagues of the power of the behaviour setting cannot be ignored. The standing patterns of behaviour are an integral part of any understanding of the use of places. On the one hand, human conceptualisations of places, together with the related intentions and purposes for being there, and on the other what happens where, are two aspects of the same process.

It was Winston Churchill who summarised this interaction with his characteristic eloquence. During the Second World War, after the Houses of Parliament had been bombed, he led the debate on the rebuilding saying:

"On the night of May 10, 1941, with one of the last bombs of the last serious raid, our House of Commons was destroyed by the violence of the enemy, and we have now to consider whether we should build it up again, and how, and when. We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us. Having dwelt and served for more than forty years in the late Chamber, and having derived very great pleasure and advantage therefrom, I, naturally, should like to see it restored in all essentials to its old form, convenience and dignity."

28 October 1943 to the House of Commons (meeting in the House of Lords).

His central argument, that was accepted when parliament was rebuilt in 1950, was that the old House of Commons should be recreated as it had been, even though there were not enough seats for every Member of Parliament to have a place, as well as a number of other inefficiencies. Churchill argued against any increased efficiency saying that democracy has been threatened in other countries by “giving each member a desk to sit at and a lid to bang”. As he explained, on many occasions the Chamber of the commons would not be very full, so the smallness would maintain intimacy, whereas, at critical times it would overcrowded, with members pouring into the aisles, supporting a "sense of crowd and urgency."

Churchill thus articulated two crucial aspects of the experience of places. One is that often the symbolic qualities, the meanings that are assigned to what is going on, outweigh any simple functional analysis. The second is the ongoing interaction between places and their use:

We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.

There is no simple one-way process from environment to response, or from response to environment. There is always an unfolding dynamic system; transactions between creating an environment for what we want and how we want to use it gives rise to a sequence that leads us to then interact with that place in the way that we expect. This is a powerful and complex dynamic.

It is the power of this dynamic interaction that explains why so often we leave it so late. We find it very difficult to break out of existing habits that are structured and in their turn structure how we make use of our surroundings. They are an integrated part of who we think we are and what we see as our intentions that give meaning to our actions [5]. They all derive from our transactions with places, and the rules that guide them; ‘Rules of Place’ [8]. Simply insisting that people turn down their thermostats, or do not fill their kettles for one cup of tea, or fly less often, is not enough without setting in motion a cycle that changes our whole way of interacting with and within places.

The Psychology of Place

In English the word ‘place’ has a rich and abstract set of meanings that are not easily translated into other languages. It can imply a position in a conceptual hierarchy, ‘knowing your place’, a very small and specific location, such as your place at table, or a much larger town square, or even a city ‘the place of your birth’. It certainly carries meanings beyond a mere physical location that is often lost with translation into other languages. You cannot use the Japanese word for place, 場所 , in the sense of reducing overweening confidence, as in the phrase ‘putting a person in his place’. Although interestingly the Hebrew translation מקום can also take on the meaning of God in the sense of ‘The Omnipresent’, reflecting the symbolic qualities inherent in the idea of a location that is more than just a point in physical space.

In an attempt to grapple with the subtleties of the meaning of ‘place’ a more technical definition was developed [8]. This proposes that places are composed of three interacting components;

• the activities that give meaning to a location,

• the physical form of that setting, and

• the conceptualisations associated with those activities in that context.

This adds a richer human dimension to Barker’s ‘behaviour setting’, recognising that for example, a band rehearsal crammed into a shed is different from the same rehearsal on the stage where it may be eventually performed.

This sense of place is what Goldsmith was reaching for. It is the concept of particular types of natural places - the school, the church, the pub – the places that define the community which have a social psychological, a physical and an active component to them. It is these conceptual, physical and use components which gives places meaning and create the pattern of use that are so difficult to break. How places are used is not casual or arbitrary. It is part of a complex, evolving set of social norms and personal habits that are very difficult to modify, being a major cause of the lethargic response to climate change.

Primary Place Definition

The mechanisms that shape the psychology of place use can be illustrated by considering places that are not actually buildings in any very strong sense. The most elementary example is a standing stone such as that illustrated in (Figure 1) [16].

These stones and their modern equivalents designate a particular location as being significant. The stone indicates that the location has power beyond its mere presence. It has meaning. It has symbolic qualities. Furthermore, within any given culture it will have sets of activities associated with it. Once a location is designated - ‘This is the spot’ - it becomes a ‘place’. For example you may arrange to meet someone there to eat your sandwiches. Or it may be where you bury the remains of your ancestors. Or it may be a crucial threshold between two places.

A place is given significance primarily by designation. This illustrates how readily a psychological load can be applied to any location. The human environment is therefore replete with places of varying forms and degrees of significance. Any modification of the environment interacts with these issues of meaning, whether it is the introduction of a wind farm, solar panels on a roof, or more extensive life style changes that require new forms of transactions with places.

The Influence of Actions

The designation of place significance takes on meaning from the activities that do, can or ought to happen there. For example, if the seats were to be cleared out of a lecture theatre and it was used as a night club it would become a completely different place and it may actually work even more effectively than when it was originally conceived as a lecture theatre. Human interaction helps to define the meaning and give significance to the places.

This has the important consequence that there is no such thing as multiple occupancy places. One example of this is the traditional Japanese house. To the Western eye it is a completely open, neutral interconnecting set of spaces; the doors can be taken off, implying that the space is totally flexible (Figure 2).

However, a study Japanese room use [17] of these apparently flexible spaces found that each space has a distinct use. Some of them are definitely bedrooms, others are family living rooms, others rooms for entertaining visitors. Some may change from being living rooms to bedrooms at particular times of the day, but the point is it is impossible to have any place that is neutral, has no framework, or structure to its use or that can be generally used for any purpose. What happens is that every location takes on a form, a meaning an expected pattern of use.

Criminal Domains

Illustrations of the power of place meanings, and how they are integrated into human actions gain particular strength when considering behaviour outside of acceptable norms; the actions of criminals. Studies of criminals elucidate what is most strongly embedded in the human use of surroundings. This draws on the assumption that it is fruitful not to regard criminals as bizarre, unusual individuals who are monsters or completely off the scale of normal human experience. Rather it is fruitful to recognise that although the reasons for their actions may be difficult to understand and totally unacceptable, what they do, particularly how they go about it represents a natural way of dealing with the world that has its roots in the way most non-criminal individuals operate.

These natural ways of dealing with the world may actually be shown more clearly in criminal activity because the criminal’s task is can be seen as almost primordial. Offenders are seeking to obtain a resource whilst trying to avoid their ‘predators’ – the police and other people who may stop them doing what they want. It is reasonable to assume that they want to obtain their objectives as efficiently as possible, with minimum effort in relation to the goods they want to steal or some other gratification.

The process involved is easier to understand when considering one type of criminal, say a prolific burglar. Such a person needs to have some idea of where the opportunities for crime are and to organise his offending in relation to his understanding of those possibilities. In other words the criminal has to imagine the possibilities for burglary in order to guide his (or sometime her) actions.

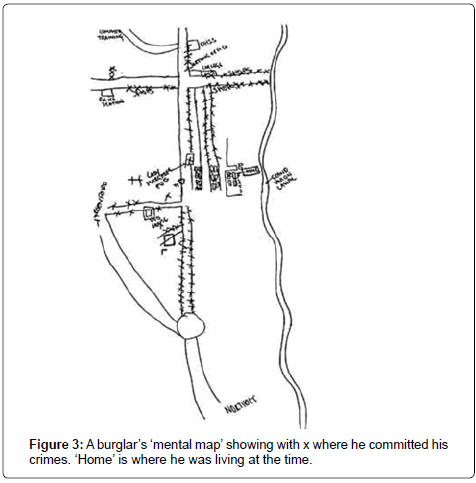

It is therefore interesting to explore burglars’ conceptualisations of places for crime using techniques that environmental psychologists used for examining how people in general make sense of their surroundings. One such approach is to ask people to draw sketch maps of the areas in which they operate. This provides an insight into their internal representation of those places. Drawing from a range of studies [18], Figure 3 shows a sketch map drawn by a prolific burglar in response to the instruction: ‘Please draw a map of the area in which you committed your crimes and indicate where the crimes are and where you were living’. This sketch map can thus be regarded as an indication of the burglar’s mental map of that area (Figure 3).

This map has a lot of interesting components to it that shows us how people give shape to an understanding of places. For instance, the area of his offending activity is demarcated by the police station at the top. He appears willing to commit crimes near the police station but not past it because when returning from a crime is the time an offender is most vulnerable. Another limit of his domain is DHSS where he obtained his unemployment benefit. There is also a roundabout that defines another extreme of his area. To the right of the sketch map, on the far side of the canal from where he is based, is for him ‘no-man’s-land’. His home sits within this demarcated area.

Figure 3 illustrates a pattern that we have found for remarkably more offenders than might be expected [18]. A distinct domain exists that is structured around his home. It might be thought that offenders would deliberately travel far a-field and although quite a high proportion do, it is much more common for them to use the area around their residence as shown in this ‘mental map’. They create their own rules of place that form a milieu in which they are comfortable committing their crimes.

This area, which has some analogies to a territory for action, is delimited further by cognitive processes which distil the experience and reduce it to an even more distinctly bounded place. This can emerges by comparing the sketch map with an actual map of the area. The main road is not in fact parallel to the canal. The cross-roads are not at rightangles. The area across the canal has rather different housing from the area in which he lives as well as some open playing fields, leading to it being of no criminal interest to him. The net effect of all this is to make the area he operates within appear to be much more distinct and much more clearly circumscribed than is actually the case. Instead of an area on a map it has become a place for burglary that provides opportunities for offending action within distinct boundaries.

Leaving It too Late

It has been argued above that any location carries powerful meanings that help to form what goes on there, which in turn strengthens the expectations of how a place is to be used. These meanings are not independent of the person and the view that individual holds of his/her characteristics. As a consequence this cycle of action and expectation is remarkably difficult to break, being influenced by the physical presence of the location itself.

The significance of all this is illustrated in human actions in many emergencies. The existing patterns of behaviour are extremely difficult to break so people continue with them despite growing evidence that it may be extremely dangerous to do so. That is how emergencies become disasters.

One example that illustrated this very graphically was a study I did in the early days of planning the Channel Tunnel train link when consideration was being given to evacuation of the trains in an emergency. Engineers wanted to see how quickly people would evacuate from their cars. To explore this, a simulation was established such that volunteers would drive into a mock-up of the tunnel train and then wait as if they were on a journey. At varying lengths of time from their initial entry into the mock-up a car at the front of the train would give out cosmetic smoke, looking as if it were on fire. The idea was to observe how long it would take people to evacuate once they noticed this apparent emergency. The time to evacuate would then be used for various engineering calculations.

To the surprise of the engineers overseeing the simulation what happened was that the first time it was run the smoke completely filled the mock-up compartment whilst all the volunteers were still sitting in their cars. To car users their car is a distinct place, one in which they generally feel quite safe. On any journey it is only evacuated under extreme conditions, where the interpretation of the rules requires a radical reconsideration. In a compartment filling up with smoke it is much more natural to wind up the windows and wait to see what transpires than to leave the comfort of the car for some unknown location in which the rules of use are quite ambiguous.

There are some general issues here of direct relevance to any policy intended to wean people from their cars. There is a need to create alternative places that people will feel equally comfortable within and that will provide the forms of self-identity that cars offer. This is of course possible as the millions of commuters around the world illustrate, but in the main they are people who have developed a pattern of place use that incorporates commuting. They already think of themselves as ‘commuters’ for their daily journeys. The even more significant example of getting out of general, existing patterns of environmental abuse is also illustrated by people refusing to re-examine their dealings with their milieu despite indications of imminent danger.

An even more graphic example of how the rules of place can give rise to disasters emerged in a major study of football grounds [8]. This study was a response to a number of deaths that had occurred in football ground disasters in England during the previous decade. Although the study was commissioned by the 1986 Popplewell Enquiry into crowd safety and control at sports grounds the results were published quickly in a book. In that book it was predicted that if there were not a radical change in the whole experience and nature of the places that are football grounds then further disasters would occur.

Just as the book was about to be published, the Hillsborough disaster occurred in which 96 people were killed. The analysis of what people expected at football grounds showed the destructive cycle that was developing. There was a growing mood that football was not a place for families or those who wanted to avoid aggression. The facilities were appalling, whether it was the food available, the discomfort of watching the match, or the toilets, further driving away those who wished for entertainment rather than some form of tribal belligerence. The deaths at Bradford City Football Ground and at Hillsborough were a direct consequence of the places where football was played moving away from being places of entertainment and moving towards being places of unruly crowds. Fortunately the idea that the whole football experience needed to be changed, rather than just strengthening barriers between supporters did find its way into the management of football clubs to the extent that the cycle could be reversed. This was achieved in part by changing the symbols of place use. The terraces where people huddled together in macho unity were replaced with seats and the supporters were provided with facilities that recognised they were paying customers and expected to behave appropriately.

Another example of the power of the patterns of expectations of place use emerged in the King’s Cross fire in which 31 people died [3]. The fire occurred on the escalator and people were guided from the underground train platforms below round through the building by police officers who did not have a full understanding of the three dimensional layout of this complex multi-level building. The consequence was that people were guided back up into the main ticket hall into which the smoke, and then flames from the fire were pouring.

From consideration of where the victim’s bodies had been found and interviews with associates and some of the people who had escaped, it was possible to establish the actual routes taken by people who were caught up in the conflagration and died [3].

What emerged was that the paths they had been taking were related directly to the routes that they would normally have been travelling along on days when there were no emergencies. Even in those last minutes, people were still involved in their day-to-day activities, in their own patterns of use of those places that they knew and experienced. Perhaps the saddest illustration of this was the person who died in one of kiosks, staying at his post as the smoke billowed around him.

The First Law of Human Action

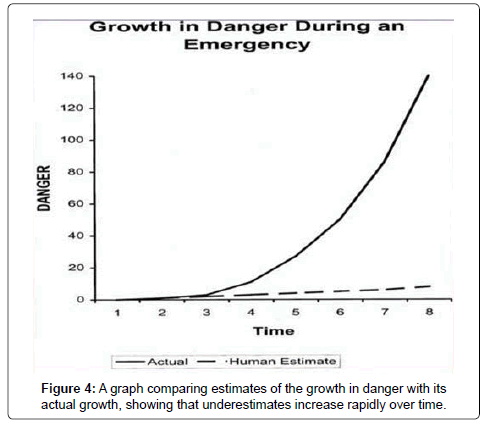

All these examples illustrate what might be thought of as a law of human activity that parallels Newton’s first law of motion. People carry on with their existing behaviour unless some external force leads them to recognise that some new set of rules are now guiding their use of place. This gives rise to regular mis-estimates in the development of danger [19]. This can be illustrated by the graph in Figure 4. There the difference between how people think danger grows and how it typically does grow is represented (Figure 4).

Broadly speaking people think that danger grows in a simple linear fashion when it tends to develop in an exponential or geometric way. In the early stages, therefore, the estimates of growth are reasonably accurate. This lulls people into thinking that they understand what is happening, but their estimates become ever more inaccurate as time moves on until the emergency gets out of control.

The reasons for this inertia are the existing patterns of behaviour and our understanding of what is expected of our interactions with each other and with the places that we know. It takes a major jolt to get us to re-evaluate what we think is happening and to change how we think of ourselves and our activities. We have to recognise that the place we are at has changed so that different rules apply – until that is the case, we are reluctant to change our behaviour.

This behavioural inertia is what happens in small scale disasters where people die in their own homes, major industrial accidents such as Piper Alpha and the Herald of Free Enterprise, and even in large scale international disasters such as Rwanda and Bosnia. There is always an ignoring of early indicators of danger with the consequent delay in recognising that something needs to be done. This continues until the indicators of danger are so overwhelming that decision makers can then accept that the situation has changed to something so different that they can now apply new rules. By then it is often too late and so disaster is inevitable.

It is worth emphasising this central point. Emergencies become disasters because initial warnings are ignored. They are not ignored out of obstinacy or ignorance but because of the psychological processes that underlie habitual patterns of activity that have been described. The examples are all too familiar. Recent railway disasters came about in a climate in which trains were going past signals set at danger. Before the New Orleans floods many people said the levees needed to be developed and strengthened and that more money needed to be put into flood control. It was all highly predictable but the processes in place stopped that happening.

Why Do We Leave It So Late?

The central argument here is worth restating. The delay in responding to environmental threats is analogous to the typical human delays in responding to any danger that requires a different set of rules for how places are made use of. We leave it so late for a number of basic reasons.

• Existing environmental cues are extremely strong and layered with meaning.

• Consequently although early warnings are there they conflict with established interpretations of what we do and where we do it.

• Typically then the emerging indicators of an emergency are not strong or clear enough to allow people to change their expectations and consequent actions.

• Because of these ambiguities we wait for further information; we check things out with people, we explore the possibilities to see whether we should be behaving differently from the way we do normally.

• Human beings have tremendous difficulties in assessing probabilities, so we rely on the existing signals we see directly to assess any risks.

• We therefore each interpret probabilities of danger in different ways depending on our circumstances. The situation we are in may give a different perspective from others, especially experts such as statisticians and engineers and economists.

• A person continues with the current activity of rest or unthinking motion unless acted on by some external or internal force. We have a natural inertia because normally that is essential for survival within a social context; working and relating to each other.

The general response to climate change therefore will be shaped by the same inertia that made, for example, football grounds so dangerous before the deaths of hundreds of supporters, in what were meant to be places of entertainment, produced a radical change in how they were built and manage. These were changes in the meanings and rules of place, facilitated by both the management of those places and their physical form, as well as changes in what behaviour people there expected of each other.

Is there a Way of Reducing Human Inertia?

What processes are implied by this psychological analysis that would encourage people to behave differently in relation to the environment?

1. It is essential to reduce the ambiguity. As long as there is debate about what, if or how climate change may occur people will be reluctant to adopt different behaviours.

2. New socially accepted rules of place use have to emerge. The example of the smoking ban is an excellent illustration of this. For many years I have tried to dissuade people from smoking in my house but with varying degrees of success. But now it is no longer acceptable across a range of settings I do not even have to ask.

3. Sadly, one way of encouraging such changes is by what is sometimes called ‘management by crisis’. The powers that be have the change in behaviour planned, but wait until the situation is so serious that people will then believe that the situation is so different they have to change. Sometimes they may even generate the crisis to get the change they want.

4. What is required is that there is a change in what people expect of each other. This is a fundamentally social process. It is not about shouting at people, or burying them under facts. It is giving people a framework for developing a new way of acting in the world, a new way of thinking about themselves and thinking about their relationships to others.

5. All of this can be stimulated by built forms that speak of energy conservation and symbolise differences in human actions. This is where the contributions of the architectural and environmental imagination will be most powerful.

References

- Sunstein CR (2007) On the Divergent American Reactions to Terrorism and Climate Change. Columbia Law Review 107: 503-557.

- Cronon W (1996) The Trouble with Wilderness: or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature. Environ Hist 1: 7-28.

- Donald I, Canter D (1992) Intentionality and Fatality during the King’s Cross Underground Fire. Eur J Social Psych 22: 203-218.

- Canter D, Comber M, Uzzell D (1989) Football in its Place: An Environmental Psychology of Football Grounds London: Routledge. National Library of Australia, Australia.

- Devine-Wright P (2011) Place attachment and public acceptance of renewable energy: A tidal energy case study. J Environ Psych 31: 336-343.

- Korpela KM (1989) Place-identity as a product of environmental self-regulation. J Environ Psych 9: 241-256.

- Gustafson P (2001) Meanings of Place: Everyday Experience and Theoretical Conceptualizations. J Environ Psych 21: 5-16.

- Canter D (1977) The Psychology of Place. London: Architectural Press, UK.

- Fullilove MT (1996) Psychiatric implications of displacement: Contributions from the psychology of place. Am J Psychiatry 153: 1516-1523.

- Canter D (Ed.) (1970) Architectural Psychology. London: RIBA Publications, UK.

- Barker RG, Wright HF (1955) Midwest and Its Children" New York: Row and Peterson, USA.

- Barker RG (1965) Explorations in Ecological Psychology. Am Psychol 20: 1-14.

- Barker RG, Gump P (1964) Big School Small School: High School Size and Student Behaviour, Stanford University Press, USA.

- Gifford R ( 2007) Environmental Psychology: Principles and Practice Seatle: Optimal Books, USA.

- Canter D (2001) Health and Beauty: Enclosure and Structure in Aesthetics, in Birgit Cold (edn.). Well-being and Health. Farnham: Ashgate. 49-56.

- Canter D, Lee KH (1974) A non-reactive study of room usage in modern Japanese apartments. Psychology and the built environment 48-55. Kent: Architectural Press, Tonbridge, USA.

- Canter D, Youngs D (2009) Investigative Psychology: Offender Profiling and the Analysis of Criminal Action. Chichester: Wiley, USA.

Citation: Canter D (2013) Why do we Leave it so Late? Response to Environmental Threat and the Rules of Place. J Earth Sci Clim Change 5: 169. DOI: 10.4172/2157-7617.1000169

Copyright: ©2013 Canter D. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.