Research Article Open Access

Violence in Hip-Hop Journalism: A Content Analysis of the Source, A Leading Hip-Hop Magazine

Oredein T*School of Public Health, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Piscataway, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- Oredein T

School of Public Health

University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

Piscataway, USA

E-mail: oredeity@umdnj.edu

Received Date: June 20, 2013; Accepted Date: July 17, 2013; Published Date: July 19, 2013

Citation: Oredein T (2013) Violence in Hip-Hop Journalism: A Content Analysis of the Source, A Leading Hip-Hop Magazine. J Community Med Health Educ 3:223. doi: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000223

Copyright: © 2013 Oredein T. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Objectives: This study seeks to determine the prevalence of violence in a popular hip-hop entertainment magazine, a previously overlooked medium. Methods: We performed a content analysis on a random sample of 48 issues of The Source Magazine and coded magazine covers, and feature articles about celebrities and accompanying photographs for the presence of violent content.

Results: 35% of covers contained at least one violent category in text or graphics. Nearly 80% of feature articles contained at least one violent category in the text and approximately 30% of feature articles were accompanied by at least one violent graphic.

Conclusion: Findings suggest that The Source Magazine and possibly other hip-hop entertainment venues are a potential source of mediated modeling for violent behaviors.

Keywords

Hip-hop; Entertainment journalism; Violence; Behavior modeling; Mediated modeling

Introduction

Since the mid-1980s hip-hop has been criticized for its heavy violent content and credited with encouraging violence. Although often justified as a reflection of urban life, the prevalence and portrayal of violence in hip hop and the potential ramifications have become a focus of research [1]. Several studies found that hip-hop has consistently had a higher prevalence of violent portrayals [2-4] and greater effects on violence and aggression than other music genres, such that youth exposed to rap music were more likely to consider violence as an acceptable means to resolve social conflicts, and were more likely and to practice violent behaviors in real life [5-13].

The Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) posits mechanisms to explain how exposure to violence in hip-hop can shape violent attitudes, and behaviors. According to SCT, individuals learn vicariously by observing others perform behaviors and receive resulting rewards or punishments, which makes the observer more or less likely to perform the modeled behaviors [14]. This observational learning occurs whether the modeling is witnessed in person or through the media. Viewers are more likely to pay attention to models they consider to be similar to themselves, attractive, wealthy, and/or powerful [15-20]. Hip-hop artists are often of similar age, racial and/or socioeconomic backgrounds as their fans, and many hail from the same neighborhoods, increasing the likelihood of attraction and identification with such celebrities and their lifestyles for youth across various racial and sociocultural background combinations [21].

Adolescents often express the desire to be like celebrities in the media [22] and such wishful identification often leads young audiences to make changes in their appearance, attitudes, values, and activities accordingly [23,24] in order to emulate them. According to SCT, hiphop provides plenty of opportunities for such mediated modeling via lyrics, videos, film and even print [25-28] but so far studies surrounding the hip-hop culture only focused on lyrical content [29,30] and music videos [2,31] while print venues, such as monthly hip-hop magazines have not been assessed. Hip-hop magazines are also popular media that have the potential to impact and influence their audience. As a journalistic venue, the magazines discuss the professional and personal lives of celebrities, and where relevant reference violence in their bodies of work, as well as any real-life violent infractions. This additional exposure may contribute to reinforcing violence as a norm especially as young audiences are more likely to be interested in celebrity affairs and look to celebrities to learn how to act and how to achieve prestige [32].

Therefore, we explored the prevalence of violence appearing in The Source: The Magazine of Hip-hop Music, Culture and Politics, a popular hip-hop magazine in order to answer the following research questions:

1) What are the frequencies, and categories of violence occurring in The Source Magazine’s covers?

2) What are the frequencies, and categories of violence occurring in feature articles in The Source Magazine?

3) What are the frequencies, and categories of violence occurring in photographs that accompany feature articles in The Source Magazine?

Methods

We chose The Source Magazine because it is the longest-running and most popular hip-hop publication and has a large minority and urban youth readership [33]. It is available in The New York Public Library system. Since large portions of issues were not available for 1988 through 1990 the study excludes the first three years of the publication. The sampling frame was all issues between 1991 and 2006. We randomly selected three issues per year using the web-based Research Randomizer random number generator and photocopied each magazine’s cover, table of contents, and relevant articles along with their related photographs. The final sample was 48 magazines.

We coded each magazine’s cover because covers are generally designed to attract readers. Covers were coded for celebrity subject, occupation, and any violent graphics or text. We also coded celebritybased “Feature Articles” because they have been a part of the magazine’s formatting across the span of the publication, and it is the only element consistently appearing in every issue. Furthermore, The Source Magazine’s feature articles mostly consist of interviews with highprofile celebrities. The interviews provide an opportunity for modeling behaviors as it is a forum for celebrities, who often have role model status, to discuss their bodies of work in addition to their real lives. We identified “Feature Articles” by the listings under the heading “Feature Articles” in The Source’s “Table of Contents”. A Feature Article was eligible to be coded if its subject was a specific celebrity or group entity. Montage articles featuring several unrelated artists or groups (i.e. “The 100 Greatest R&B Singers of All Time”), articles solely about fashion, and articles about violence within the hip-hop, minority, and/or urban communities, were not coded. However, coders recorded if the latter category was present. We recorded relevant articles for subject persona, occupation and violent reputation. All relevant articles were coded at the sentence level for violent content and anti-violent statements within the text. Pictures accompanying the articles were also coded for violent graphics. The text was also reviewed for illustrative quotes. Relevant examples of violent categories were recorded during the coding process for inclusion in the manuscript.

Coding

The coding scheme was developed deductively based on the research questions and information from prior research [34] and inductively based on initial reviews of The Source Magazine’s feature articles. Violence was defined as aggressive physical or verbal actions occurring in real life or art projects (i.e. lyrics, videos, movies). We coded each article for violence according to the following violent categories: feuding/verbal violence; physical assault; murder/attempted murder; weapons ownership or use; sexual assault; gang activity; robbery; vandalism; being the recipient of violence or some other violence (e.g. self-inflicted violence). Each mention of general violence in music (i.e. “gangsta rap”, “hardcore lyrics”), violent reputations (i.e. terms “thug”, “gangsta”, “G”, “O.G.”, “live nigga”, and “street soldier” or other terms indicating a tough persona), violent neighborhoods, and violent metaphors were coded as well. Coding was not mutually exclusive. We also coded the article’s layout to capture whether it included enlarged, prominently placed excerpts from the article containing violent text.

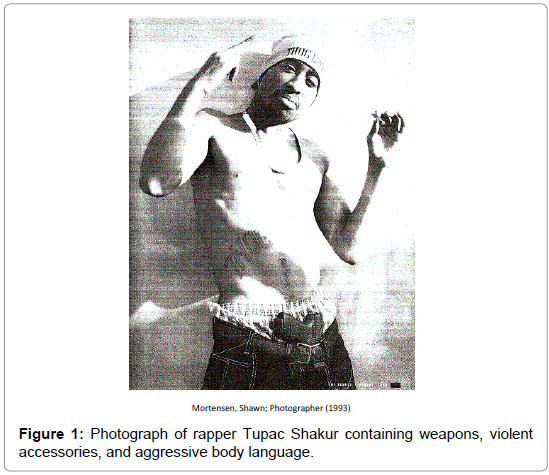

We coded each unique photograph within each Feature Article for weapons; violent accessories (i.e. clothing, tattoos or jewelry with violent graphics (e.g. picture of guns); aggressive body language or posturing (i.e. scowling, fighting stances, hand gestures); and/or other violence (e.g. spattered blood, bullet holes). Each violent image in a photograph was coded. Coding was not mutually exclusive.

A second coder, a public health doctoral student at the time of the study, independently coded a sub-set of 20 randomly selected magazine articles. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was calculated to determine the percent agreement beyond chance. The average agreement was 0.791 across text variables some of which had moderate agreement and others of which had near perfect agreement [35] (range: 62.5-100), and .982 across photograph variables (range: 87.5-100).

Statistical analysis

We used the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS®) version 14.0 for all analysis. We ran Chi-square analyses and used a standard alpha level of p < 0.05 to determine statistical significance.

Results

Cover analysis

Each of the 48 covers in the sample featured a celebrity. More than a third of covers contained at least one instance of violence in the form of weaponry (6.3%, n=3), violent accessories (12.5%, n=6), aggressive body language (14.6%, n=7) or other violence (22.9%, n=11), mainly violent language in headlines highlighting features within the issue (Table 1).

| (%) | (N) | |

| Magazines Coded | - | 48 |

| Any Violence in Magazine | 100.0 | 48 |

| Covers Coded | 100.0 | 48 |

| Cover Graphic of Celebrity | 100.0 | 48 |

| Any Cover Violence | 35.4 | 17 |

| Articles Coded | 100.0 | 218 |

| Articles with Any Violence | 79.4 | 173 |

| Articles with only 1 depiction of violence | 5.0 | 11 |

| Articles with 5+ depictions of violence | 48.2 | 105 |

| Pictures | 100.0 | 959 |

| Pictures with Any Violence | 28.4 | 62 |

Table 1: Magazine analysis.

Feature article analysis

We coded 218 feature articles. An average of 4.29 (s.d.=1.48) feature articles per magazine met the coding criteria. Articles averaged 4.5 pages (s.d.=2.10) in length. The majority of featured subjects were primarily rappers (85.3, n=186).

Almost 80% of articles contained at least one instance of violence in the text, and almost half had five or more. The most prevalent category was having violent reputations, appearing in 45% of articles.

“[Slim] was a gangsta... By all means necessary [36].”

Weapons appeared in approximately 40% of articles and the majority of these (81.6%) mentioned firearms.

“...Free was released from Tehachapi State Prison after serving nine months for possession of a SKS assault rifle and kidnapping... [37]”

“Spice pulls his Glock from his jeans, lays it on the table and slides comfortably into the nearest chair [38].”

General mentions of violent media (i.e. music, videos and films) appeared in about 40% of articles.

“Fat Joe won’t be going soft anytime soon, as you’ll see by the majority of straight-up hardcore songs on the album. Even Puff Daddy’s contribution, the CD’s title track, sounds like the dark, pianoand- strings driven soundtrack to an urban crime tale [39].”

Feuding appeared in 36.7% of articles.

“... [Nas] went on a one-man rampage against New York radio station Hot 97 for not allowing him to bring gallows onstage to symbolize the lynching of his then nemesis, Jay-Z [40].”

“Major rappers like Beanie Sigel and Jadakiss and Nas, Prodigy and Jay are now going at each other with fervor [41].”

Recipients of violence appeared in 34% of articles. The majority of recipients (61.3%) were murder victims, followed by non-fatal shootings (37.3%).

“...an unknown assailant fired a 9mm pistol multiple times into the black vehicle’s rear window. The young man in the Dodges’ backseat attempted to retaliate but was shot nine times in the process [42].”

Roughly 30% of articles made mentioned living in violent neighborhoods.

“Raised on the rugged streets of Chicago’s famously gang and pimp saturated West Side... [43].”

Almost 15% of articles use a violent metaphor, most of which (71.4%) were posed by the article’s author.

“As Mike the driver artfully negotiates this boat of a stretch limo through evening mid-Manhattan traffic, Knight and Kenner strategize a little, but mostly they sit in silence like two hit men on their way to do what they gotta do [44] ”

“...and his eyelids drop like two guillotines falling in slow motion... [45]”

Fifteen percent of articles mention other violence such as animal cruelty or suicide. Eleven percent boldly featured a violent text excerpt within the article’s layout.

Expressions of anti-violence were present in 35% of articles, and included sentiments or actions taken to reduce violence.

“He employed many from the city of Compton at Ruthless Records and was quick to contribute some of his big bank to anti-gang efforts... [46]” (Table 2).

| Violence Category | Total Articles (%) | Total Articles (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 100.0 | 218 |

| Any Violence | 79.4 | 173 |

| Violent Categories | ||

| Violent Reputation | 45.0 | 98 |

| Violent Media | 40.8 | 89 |

| Weapon | 39.9 | 87 |

| Feud/Conflict | 36.7 | 80 |

| Recipient of Violence | 34.4 | 75 |

| Violent Neighborhood | 29.4 | 64 |

| Fighting/Assault | 23.9 | 52 |

| Murder | 21.1 | 46 |

| Gang Activity | 16.5 | 36 |

| Violent Metaphor | 14.7 | 32 |

| Robbery | 9.6 | 21 |

| Vandalism | 4.6 | 10 |

| Sexual Assault | 3.2 | 7 |

| Other Violence | 14.7 | 32 |

| Anti Violence | 34.9 | 76 |

Table 2: Prevalence of articles that contain violence according to violent categories.

Photograph analysis

Collectively we coded 959 photographs, 62 of which had at least one violent graphic. Almost 30% of articles contained at least one photograph featuring violent graphics. Aggressive body language was the most common category occurring in about 84% (n=52) of violent photographs (Figure 1 and Table 3).

| Photo Category | Total Articles(%) | Total Articles(Frequency) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Articles | 100.0 | 218 |

| Articles with any Violent Graphics | 28.4 | 62 |

| Violent/Aggressive Body Language | 23.9 | 52 |

| Weapons | 4.1 | 9 |

| Violent Accessories | 3.2 | 7 |

| Other Violent Graphics | 4.6 | 10 |

Table 3: Prevalence of articles that contain at least one violent photograph.

Discussion

Several components of hip-hop culture have been analyzed for violence and subsequently linked with aggressive and violent behaviors, however this is the first time that a hip-hop magazine has been reviewed for its violent content, and considered for potential implications. With 84.5% of articles containing violence within the text and/or photographs. The Source Magazine is a potential source of mediated modeling for violent behaviors. Of the articles containing violence, 95% had more than one violent depiction, and 73.3% had five or more depictions. As magazine covers and content are designed to attract readers, the celebrities featured in and on The Source Magazine were most likely chosen to cater to and meet the demand of the magazine’s audience. It is possible that celebrities with violent, controversial or otherwise colorful lives and careers are deemed to be more marketable with respect to magazine sales, and such celebrities are therefore featured more often and more prominently. Nonetheless, the high prevalence is still of particular concern as repeated exposure to violence in the media not only can normalize violence [47] but it may contribute to desensitization [48], resulting in reduced tendencies to intervene in violent scenarios [49], help others in distress [50], and have sympathy for victims of violence [51,52]. It also may make it easier for others to commit violence without having to experience the negative emotions and psychological reactions [25-28].

With respect to violent categories, having a violent “thug” reputation was the most prevalent and perhaps it is indicative of the importance paid to the phenomenon of the violent identity and reputation that is so pervasive in hip-hop culture [29,53]. Weapons were the second most prevalent category and firearms specifically were mentioned in one-third of articles, which exceeds the 27% of music videos featuring guns [2], and their 18.7% prevalence in primetime television shows [54]. Feuding was the third most common category represented in 37% of articles. One issue (December 2001) designated itself “The Beef Issue” and interviewed four subjects that were involved in high profile feuds at the time. In pictures, aggressive body language was the most popular, again perhaps related to the importance of violent identity and reputation.

The Source magazine was chosen because it is the longest running hip-hop magazine with a large youth readership. Even with the increase in electronic media, The Source had an estimated readership of 1.5 million in 2008, and has a large minority and youth following [33]. However, since this study only included one magazine, it is impossible to discern if the violence is excessive for hip-hop, music, pop culture or entertainment magazines in general. The sample was also limited to three issues per year. Some issues may have contained inflated mentions of violence due to articles covering the high-profile, violent deaths of popular rappers. Due to our interest in examining modeling, only selected feature articles about celebrities were coded. However, in all probability this resulted in an underestimation of violence appearing in The Source Magazine as other articles, columns, photographs, and advertisements, many with celebrity foci, were not included in the analysis. Also, most issues were photocopied in black and white, making it difficult to assess some graphic concepts such as identifying certain tattoos, which likely resulted in an underestimation of violent graphics. Lastly, this study did not analyze the way violence was framed with respect to positive or negative portrayals, which may also influence the way violence is interpreted.

We suggest that hip-hop music entertainment magazines, and possibly other similar venues, have the potential to impact their young audiences. Violent perpetrators in hip-hop culture are often high-profile subjects with whom their followers identify and who they revere, so future research should explore additional hip-hop media outlets such as websites, and urban radio stations for violence. In addition, there may be additional effects when the featured violence can be perceived as real as opposed to artistic portrayals. Future research should focus on the positive or negative portrayals, prevalence and presentation of real-life violent transgressions, as well as the audience’s perceptions of violence, varying mechanisms for processing violence, and variables that moderate these processes in order to better inform violence prevention interventions.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to Olivia Wackowski, Ph.D. who was instrumental in determining inter-coder reliability.

Human Subjects Statement

There were no human subjects involved, therefore no IRB review or permissions were required.

References

- Chang J (2006) Total chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip-Hop. New York: Basic Books.

- Smith SL, Boyson AR (2002) Violence in music videos: Examining The Prevalence and Context of Physical Aggression. J Commun 52: 61-83.

- DuRant RH, Rich M, Emans SJ, Rome ES, Allred E, et al. (1997) Violence and weapon carrying in music videos. A content analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 151: 443-448.

- Rich M, Woods ER, Goodman E, Emans SJ, DuRant RH (1998) Aggressors or victims: gender and race in music video violence. Pediatrics 101: 669-674.

- Chen MJ, Miller BA, Grube JW, Waiters ED (2006) Music, substance use, and aggression. J Stud Alcohol 67: 373-381.

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Bernhardt JM, Harrington K, Davies SL, et al. (2003) A prospective study of exposure to rap music videos and African American female adolescents' health. Am J Public Health 93: 437-439.

- Johnson JD, Jackson LA, Gatto L (1995) Violent Attitudes and Deferred Academic Aspirations: Deleterious Effects of Exposure to Rap Music. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 16: 27-41.

- Anderson CA, Carnagey NL, Eubanks J (2003) Exposure to violent media: the effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. J Pers Soc Psychol 84: 960-971.

- Rubin AM, West DM, Mitchell W (2001) Differences in Aggression, Attitudes Toward Women, and Distrust as Reflected in Popular Music Preferences. Media Psychology 3: 25–42.

- Hansen CH., Hansen RD (1990) The Influence of Sex and Violence on the Appeal of Rock Music Videos. Comm Res 17: 212-234.

- Miranda D, Claes M (2004) Rap Music Genres and Deviant Behaviors in French-Canadian Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 33: 113-122.

- Tanner J, Asbridge M, Wortley S (2009) Listening to Rap: Cultures of Crime, Cultures of Resistance. Social Forces 88: 693-722.

- Devlin JM, Seidel S (2009) Music Preferences and Their Relationship to Behaviors, Beliefs, and Attitudes toward Aggression

- Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura A (1994) Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In: J Bryant D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale 61-90.

- Bandura A (2001) Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication. Media Psychololgy 3: 265-299.

- Harwood J (1997) Viewing age: Lifespan identity and television viewing choices. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 41: 203-213.

- Harwood J (1999) Age identification, social identity gratifications, and television viewing. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 43: 123-136.

- HICKS DJ (1965) IMITATION AND RETENTION OF FILM-MEDIATED AGGRESSIVE PEER AND ADULT MODELS. J Pers Soc Psychol 34: 97-100.

- Hoffner C, Cantor J (1991) Perceiving and responding to mass media characters. In: J. Bryant D. Zillmann (Eds.), Responding to the screen: Reception and reaction processes. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum 63-101.

- Cohen J (2001) Defining Identification: A Theoretical Look at the Identification of Audience with Media Characters. Mass Communication and Society 4: 45-264.

- Hoffner C, Buchanan M (2005) Young Adults’ Wishful Identification with Television Characters: The Role of Perceived Similarity and Character Attributes. Media Psychology 7: 25-351

- Boon SD, Lomore CD (2005) Admirer-celebrity relationships among young adults: Explaining perceptions of celebrity influence on identity. Human Communication Research 27: 432-465.

- Caughey JL (1986) Social relations with media figures. In: G. Gumpert & R. Cathcart (Eds.), Inter/media: Interpersonal communication in a media world. (3rdedn), Oxford University Press, New York, 219-252.

- Bandura A (1977) Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall

- Bandura A (1978) Social learning theory of aggression. J Commun 28: 12-29.

- BANDURA A, ROSS D, ROSS SA (1961) Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 63: 575-582.

- BANDURA A, ROSS D, ROSS SA (1963) Imitation of film-mediated agressive models. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 66: 3-11.

- Kubrin CE (2005) Gangstas, thugs, and hustlas: Identity and the code of the street in rap music. Social Problems 52: 360-378.

- Adams TM, Fuller DB (2006) The Words Have Changed But The Ideology Remains The Same Misogynistic Lyrics In Rap Music. J Black Stud 36: 38-957.

- Conrad K, Dixon T, Zhang Y (2009) Controversial Rap Themes, Gender Portrayals and Skin Tone Distortion: A Content Analysis of Rap Music Videos. Journal of Broadcasting Electronic Media 53: 34-156.

- De Backer CJS, Nelissen M, Vyncke P, Braeckman J, Mc Andrew FT (2007) Celebrities: From Teachers To. Human Nature 18: 334-354.

- (2009) The Source, Inc. The 2009 Source Media Kit. New York: Source Magazine LLC.

- Mustonen A, Pulkkinen L (1997) Television violence: A development of a coding scheme. Journal of Broadcasting Electronic Media 41: 168-189.

- Banerjee M., Capozzoli, M, McSweeney L, Sinha D (1999) Beyond kappa: A review of interrater agreement measures. Canadian Journal of Statistics 27: 3-23.

- Wade C (2004) Thug’s mansion. The Source 179: 62.

- Frosch D (2001) Paper in my pocket. The Source 138: 186-188.

- Harris C (1993) Sticking to his guns. The Source 51: 54-57.

- Rodriguez C (1998) Definition of a Don. The Source 109: 184-192.

- Barrow JL (2004) Quiet storm. The Source179: 122-128.

- Parker M (2001) Still Matter. The Source 147: 166-171.

- Gotti (2002) A soldier's story. The Source 156: 186-189.

- Ivory S (1996) Family Matters. The Source 84: 124-132.

- Baker S (2004) Worth the Wait. The Source 179: 90-92.

- Alvarez G (1999) Spit Darts. The Source 115: 68-172.

- Williams F (1995) Eazy E: The life the Legacy. The Source 69: 52-62.

- Drabman RS, Thomas MH (1974) Does media violence increase children's toleration of real-life aggression? Dev Psychol 10: 418-421.

- Cline VB, Croft RG, Courrier S (1973) Desensitization of children to television violence. J Pers Soc Psychol 27: 360-365.

- Molitor F, Hirsch KW (1994) Children’s Toleration of Real-Life Aggression After Exposure to Media Violence: A Replication of the Drabman And Thomas Studies. Child Study Journal 24: 91-207.

- Zillmann D, Weaver JB (1999) Effects of Prolonged Exposure to Gratuitous Media Violence on Provoked and Unprovoked Hostile Behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol 29: 145-165.

- Linz DG, Donnerstein E, Penrod S (1988) Effects of long-term exposure to violent and sexually degrading depictions of women. J Pers Soc Psychol 55: 758-768.

- Mullin CR, Linz D (1995) Desensitization and resensitization to violence against women: effects of exposure to sexually violent films on judgments of domestic violence victims. J Pers Soc Psychol 69: 449-459.

- Kubrin C (2006) “I see death around the corner”: Nihilism in rap music. Social Perspect. 48: 433-459.

- Scharrer E Violent (2003) Media Content: A Cross-Media, Longitudinal Analysis, International Communication Association. San Diego, CA, 1-46.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 20804

- [From(publication date):

July-2013 - Dec 06, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 15908

- PDF downloads : 4896