Editorial Open Access

Some Comments on Orthopaedic Implant Infection: Biomaterials Issues

Murrr LE*Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- Murrr LE

Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering

The University of Texas at El Paso

El Paso, TX 79968 USA

E-mail: lemurr@utep.edu

Received date: June 20, 2013; Accepted date: June 21, 2013; Published date: June 23, 2013

Citation: Murrr LE (2013) Some Comments on Orthopaedic Implant Infection: Biomaterials Issues. J Biotechnol Biomater 3:e119. doi:10.4172/2155-952X.1000e119

Copyright: © 2013 Murrr LE. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Biotechnology & Biomaterials

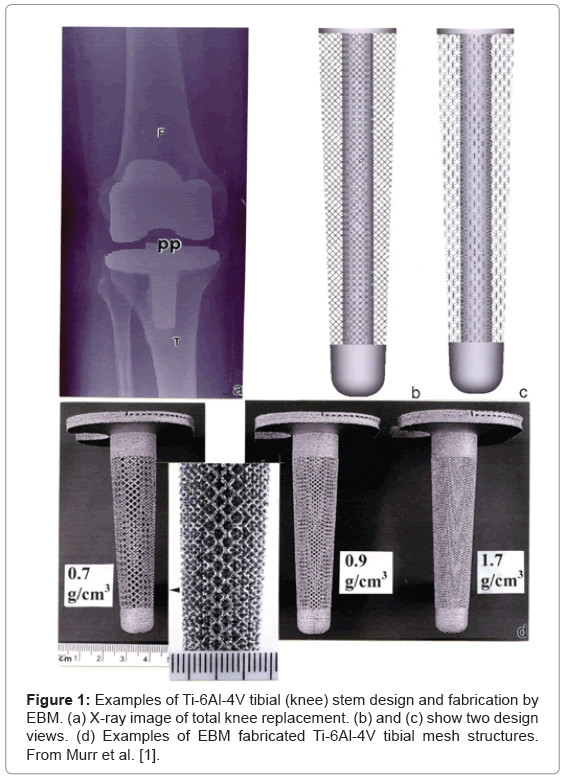

Recently we described the fabrication of so-called functional Tialloy biomedical implants by electron beam melting [1]. There were several issues which were particularly highlighted, including the prospects for fabricating patient-specific, open-cellular implants or orthopaedic appliances with closely matched stiffness to avoid any significant bone stress shielding, as well as the inducement of bone cell ingrowth to create a more stable appliance without cement. The issue of infection was also briefly addressed with the proposal that such opencellular structures might accommodate nano silver particles to serve as a long-term antibiotic within the implant; similar to the incorporation of antibiotics within implant cement compositions.

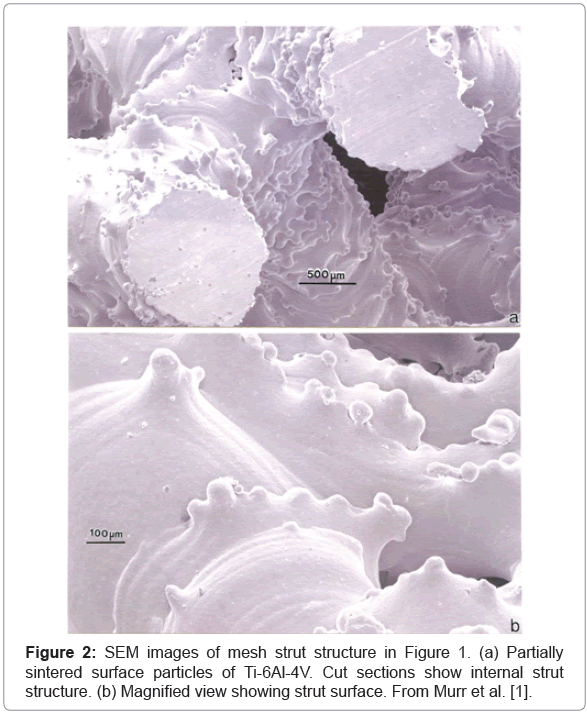

As illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 representing Figures 19 and 21 respectively from the original publication [1], the ability to control the implant density and corresponding porosity will not only allow control of the stiffness, but also the optimum open-cellular dimensions to accommodate bone cell in growth. As shown in Figure 2, the strut surface structure exhibiting some roughness-related, partial alloy melting or sintering, may also optimize the bone cell attachment. However, in contradiction to this cellular attachment optimization, Wu et al. [2] have shown, in support of related studies, that surface roughness also encourages the growth of infectious staphylococci as well as osteoblasts. According to supporting case studies of commercial orthopedic implant infections, roughly 64 percent were Staphylococcus species [2-5]. In contrast, the majority of infectious organisms found as the cause of dental implant bacteremias are Streptococcus, although other pathogens have been observed.

The major problem in orthopedic implant infection is the growth of massive mattes or biofilms of infectious bacteria which can form over the metal surface, especially roughened surface areas. The immune system cannot counter these massive infection systems, and the only recourse in most instances is the removal of the appliance and its sterilization along with the healing of the wound area intense antibiotic regimes. Most infections are hospital acquired and of the various infections which strike roughly 2 million people annually in the U.S., 0.05 percent cause death. Orthopaedic implant infection rates range from 0.3% to 8.3% [6] and occur by entry of pathogens into the wound during surgery, the spread of infection from a local source, hematogenous (blood transport) spread, or the recurrence of sepsis in a previously infected joint. With roughly 400,000 primary hip arthroplasties and nearly 1 million total knee anthroplasties in the U.S. in 2012, the market exceeds $20 B. While this market represents mostly smooth and highly polished implant components, prospects for 3D-printed or electron beam and laser beam melt-fabricated, patient-specific open-cellular appliances will require careful evaluation of the infection issue, especially in light of the continued mutation of pathogens against the most effective antibiotics. Pearson et al. [7] have recently discussed novel strategies for using bacteriophage to attack complex, infectious biofilms on surfaces. The first observations of lytic phages to cure infections date to the late 19th and early 20th centuries [8], and it was only in the 1960’s where prophylaxis and treatment of bacterial infections achieved recovery efficacy in excess of 90%.

It is of interest to note in a recent executive summary on the current state of evidence, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Dental Association (ADA) developed some clinical guidelines regarding infection strategies [6]. In the first related recommendation, the summary concludes:

The practioner might consider discontinuing the practice of routinely prescribing prophylactic antibiotics for the patients with hip and knee prosthetic joint implants undergoing dental procedures…. patient preference should have a substantial influencing role. In the absence of reliable evidence linking poor oral health to prosthetic joint infection, it is the opinion of the work group that patients with prosthetic joint implants or other orthopaedic implants maintain appropriate hygiene. These recommendations were based on the fact that no clear association between the organisms found in implant infections and those involved in bacteremia exist.

It is apparent that some thought most be given to the complex issues involving infection in the manufacture of open-cellular components represented typically in figure 1, since these implants will promote bone cell ingrowth and will be more difficult to remove if an infection necessitates their removal. The placement of these implants must consider extreme levels of sterilization and maintenance of sterile environments during surgery. Furthermore, the patient must be completely free of infection, and measures taken to eliminate bacterial vectoring and attachment to the implant surfaces, since it appears that once they have breached the protective protocols, only radical measures involving the implant removal seem successful.

References

- Murr LE, Gaytan SM, Martinez E, Medina F, Wicker RB (2012) Next generation orthopaedic implants by additive manufacturing using electron beam melting. Int J Biomater 2012: 245727.

- Wu Y, Zitelli JP, TenHuisen KS, Yu X, Libera MR (2011) Differential response of Staphylococci and osteoblasts to varying titanium surface roughness. Biomaterials 32: 951-960.

- Chiu FY, Chen CM (2007) Surgical débridement and parenteral antibiotics in infected revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 461: 130-135.

- Rao N, Crossett LS, Sinha RK, Le Frock JL (2003) Long-term suppression of infection in total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res : 55-60.

- Waldman BJ, Hostin E, Mont MA, Hungerford DS (2000) Infected total knee arthroplasty treated by arthroscopic irrigation and débridement. J Arthroplasty 15: 430-436.

- Rethman MP, Anderson PA, Kevin B, Karen CC, Richard PE, et al. (2011) Prevention of orthopaedic implant infection in patients undergoing dental procedures : Executive summary on the AAOS/ADA clinical practice guidelines.

- Pearson HA, Sahukhal GS, Elasri MO, Urban MW (2013) Phage-bacterium war on polymeric surfaces: can surface-anchored bacteriophages eliminate microbial infections? Biomacromolecules 14: 1257-1261.

- Stone R (2002) Bacteriophage therapy. Stalin's forgotten cure. Science 298: 728-731.

Relevant Topics

- Agricultural biotechnology

- Animal biotechnology

- Applied Biotechnology

- Biocatalysis

- Biofabrication

- Biomaterial implants

- Biomaterial-Based Drug Delivery Systems

- Bioprinting of Tissue Constructs

- Biotechnology applications

- Cardiovascular biomaterials

- CRISPR-Cas9 in Biotechnology

- Nano biotechnology

- Smart Biomaterials

- White/industrial biotechnology

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15285

- [From(publication date):

August-2013 - Nov 30, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10511

- PDF downloads : 4774