Research Article Open Access

Referral of Patients with Suspected Hereditary Breast-Ovarian Cancer or Lynch Syndrome for Genetic Services: A Systematic Review

Yen Y Tan1,2,3* Leonie L Noon1,5 Julie M McGaughran1,4 Andreas Obermair1,2 Amanda B Spurdle3

1School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Australia

2Queensland Centre for Gynaecological Cancer Research, Australia

3Genetics and Computational Biology Division, Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Australia

4Genetic Health Queensland, Australia

5Department of Medicine, Familial Cancer Service, Westmead Hospital, Australia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Yen Y Tan

Rm 727, Level 7 Block 6

Royal Brisbane & Women’s Hospital

Herston, QLD 4029, Australia

Tel: (07) 3346 5192

E-mail: y.tan@uq.edu.au

Received date: November 14, 2013; Accepted date: December 18, 2013; Published date: December 20, 2013

Citation: Tan YY, Noon LL, McGaughran JM, Spurdle AB, Obermair A (2013) Referral of Patients with Suspected Hereditary Breast-Ovarian Cancer or Lynch Syndrome for Genetic Services: A Systematic Review. J Community Med Health Educ 3:255. doi: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000255

Copyright: © 2013 Tan YY, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Background: Referral of individuals with suspected hereditary breast-ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome for genetic services is very important as it allows effective surveillance and prevention strategies for these individuals and their family members. However, evidence to date indicates poor recognition of both hereditary cancer syndromes, and inappropriate or under referral of patients with suspected hereditary cancer syndromes for genetic services. In this review, we summarize the most common physician-related factors important for referral of these patients for genetic services. Methods: A systematic search was conducted in both PubMed and Embase for studies published from the earliest date possible until May 1, 2013. The search terms included MeSH and Emtree headings, and free-text words: “health knowledge, attitudes, practice”, “attitude of health personnel”, “clinical competence”, “family history”, “referral and consultation”, “health care availability”, “availability of health care”, “health care access”, “accessibility of health care”, “genetic services”, “genetic counseling”, “genetic testing”, “genetic predisposition to cancer”, “hereditary neoplastic syndromes”, “familial cancer”, “hereditary cancer”, “Lynch syndrome”, “hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome”, and “physicians”. Three reviewers abstracted data and assessed quality independently, with disagreement resolved by consensus. Results: The search revealed 202 discrete citations. One hundred and twelve articles were retrieved and 41 relevant citations were assessed. Of the 41 relevant studies, 18 assessed family history documentation, 29 assessed physicians’ knowledge, 19 assessed awareness of genetic services, 29 assessed physicians’ referral patterns, and only three investigated physicians’ ability to distinguish between low- and high-risk patients. Physicians demonstrated insufficient knowledge about hereditary cancer syndromes, particularly Lynch syndrome. Family history documentation was inadequate and lacked details for proper risk assessment, and physicians were more likely to refer patients directly to a genetic service when they were aware of such services. Conclusions: This review highlights the need to improve referral of high-risk individuals and their family members for genetic services.

Keywords

Breast ovarian cancer; Genetic services; Family history; Hereditary cancer; Health care Delivery; Knowledge, Attitudes and referral practices

Introduction

Hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome and Lynch syndrome (also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, HNPCC) are the most common autosomal dominantly inherited cancer syndromes. The syndromes are accountable for about 5-10% of all cancers, and are characterized by early onset and multiple cancers in the family [1]. While individuals carrying germline mutations in the breast cancer genes (BRCA1 or BRCA2) have a 40 to 87% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer and up to 40% lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer,1 individuals with mismatch repair gene mutations have increased lifetime risk of up to 70% for developing colorectal or endometrial cancers [2]. Depending on the type of gene affected, mutation carriers also have increased risks of other cancers such as pancreas, prostate, melanoma, stomach, small intestine, ureter and kidney [1].

Detailed clinical data such as age, family history and clinicopathologic characteristics are important for identifying individuals at greatly increased risk of developing cancer due to cancer gene mutation. These individuals and their family members can then be offered accurate cancer risk assessment, genetic counseling and/ or genetic testing, and appropriate cancer screening and prevention options. Regular colonoscopy and risk-reducing hyserecttomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy have been proven to be effective for the prevention of colorectal, endometrial and ovarian cancer [3-6], as are tamoxifen and risk-reducing mastectomy for the prevention of breast cancer [7]. However, evidence to date indicates poor recognition of hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and Lynch syndrome [8,9], and inappropriate or under referral of patients for genetic services (i.e. genetic counseling and/or testing) [9-13].

In recent years, two reviews assessed physicians’ barriers to the delivery of genetic services [14,15], and the most consistent findings were a general lack of basic knowledge about genetics and lack of confidence among physicians to provide genetic services. Collection and documentation of family history among physicians were also reported to be suboptimal, as is interpretation of family history information [16]. Other reported barriers include but are not limited to lack of genetic skills, lack of awareness of genetic services among physicians, and logistical and financial barriers for patients [15]. No reviews to date have investigated how physicians’ documentation of family history, their knowledge about hereditary cancer syndromes, and their awareness of genetic services would influence referral of individuals, specifically individuals with suspected hereditary breastovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome, for genetic services. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to summarize findings regarding the referral patterns of patients with suspected hereditary breast-ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome for genetic services, and the following key questions: (i) Is family history of cancer documented adequately during patient consultation? (ii) Do physicians have sufficient knowledge to identify individuals with suspected hereditary breast-ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome? (iii) Do physicians know how or where to access genetic services? For the purpose of this paper, referral for genetic services is defined as referral of patients from non-genetic healthcare providers (e.g. general practitioners and non-genetic specialists) to genetic specialists (e.g. genetic counselors, medical geneticists, genetic nurses).

Methods

A systematic search was conducted in both PubMed and Embase for studies published from the earliest date possible until May 1, 2013. Searches were conducted independently by two reviewers (YT and LN) and a professional librarian using the following MeSH terms, Emtree headings, and free-text words: “health knowledge, attitudes, practice”, “attitude of health personnel”, “clinical competence”, “family history”, “referral and consultation”, “health care availability”, “availability of health care”, “health care access”, “accessibility of health care”, “genetic services”, “genetic counseling”, “genetic testing”, “genetic predisposition to cancer”, “hereditary neoplastic syndromes”, “familial cancer”, “hereditary cancer”, “Lynch syndrome”, “hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome”, and “physicians”.

Study selection

Studies were considered eligible if they: (i) were a chart review, observational, cohort, cross-sectional, mixed-method or qualitative studies which were peer-reviewed and published in the English language, (ii) investigated physicians’ ability to identify hereditary breast-ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome via direct (e.g. measures of knowledge) or indirect (e.g. confidence, satisfaction or comfort level) methods, (iii) assessed physicians’ documentation of family history of cancer during patient consultation, (iv) assessed physicians’ awareness of access to clinical genetic services, and (v) recorded referral of patients for cancer genetic services.

Studies were excluded if they (i) were conference abstracts, intervention study, review articles, essay, supplementary, commentary, or editorial pieces, and (ii) investigated views of patients or nonphysician practitioners.

Data extraction, synthesis and validation

Data extraction and quality assessment were undertaken by one reviewer and checked independently by a second reviewer. Studies were reviewed initially on the basis of title and abstracts, and then all fulltext manuscripts that appeared relevant were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Additional studies were identified by a citation search of all eligible papers, and of relevant published reviews.

Each selected study was mapped to the research questions and the following information was extracted: last author’s name, year of publication and country in which the study was performed, study design, participants’ characteristics, response rates and our outcome measures of interest. Our outcome measures include (i) physicians’ ability to identify hereditary breast-ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome, (ii) physicians’ documentation of family history of cancer during patient consultation, (iii) accessibility to clinical genetics services, and (iv) the referral patterns for cancer genetic services.

The results were tabulated and crosschecked for discrepancies. Differences in opinion between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages of data and key findings are described within the table of evidence. Given the lack of study homogeneity, subjects, statistical methods, research questions and outcomes, a metaanalysis to generate a pooled estimate was not performed.

Results

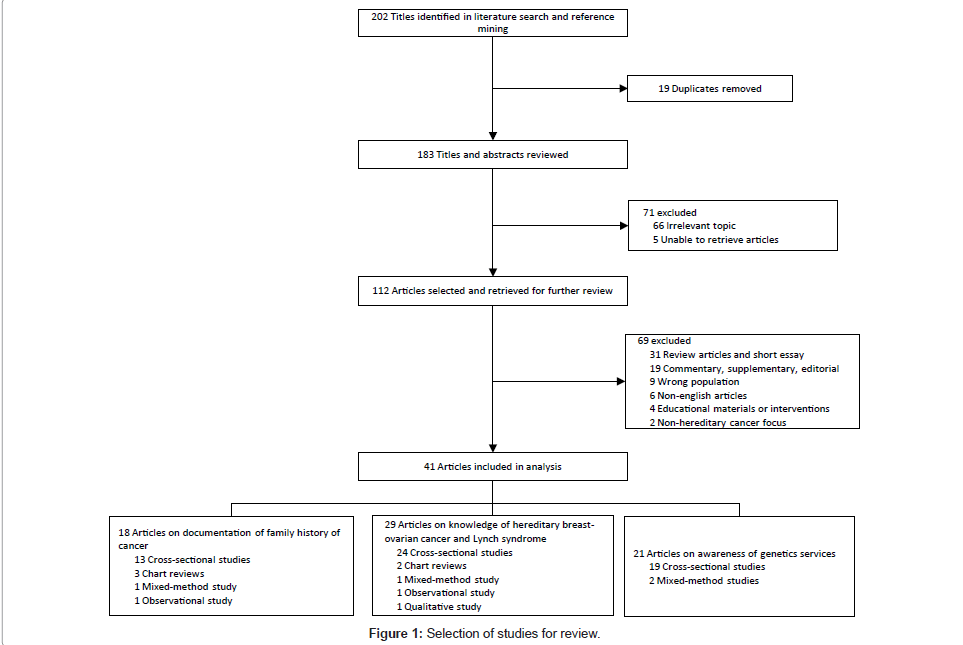

Figure 1 shows the process of study selection. Initial searching and reference mining yielded 202 discrete citations. Nineteen duplicate citations were removed. Following the first screening, 71 citations were excluded and 112 potentially relevant citations were retrieved for further review. Using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 70 publications were excluded. Initial disagreement over the selection of six publications occurred. Following discussions, two publications were included, with the remaining four publications referred to a third reviewer for arbitration. In total, 41 publications were selected for the review. Of the 41 relevant publications, 18 assessed family history documentation, 29 assessed physicians’ knowledge, 19 assessed awareness of genetic services, and 29 assessed physicians’ referral patterns. Only three studies assessed physicians’ ability to distinguish between low- and high-risk patients.

Study characteristics

The main characteristics of the study populations and outcome measures are detailed in Table 1. The majority of the studies included were cross-sectional (n=34), followed by chart reviews (n=3), mixedmethod (n=2), qualitative (n=1) and observational (n=1). Of the 34 cross-sectional studies, 24 studies originated from North America, 8 studies originated from Europe, 1 study from Turkey and 1 study from New Zealand. Other non-cross-sectional studies originated either from North America (n=6) or the UK (n=1). Of all the studies selected, 10 studies investigated hereditary breast-ovarian cancer, 7 studies investigated Lynch syndrome, 7 studies investigated both hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and hereditary colorectal cancer, and the remaining 17 investigated hereditary cancers in general. Overall, there were 29 studies examined physicians’ referral patterns.

| Author | Country | Study type | Study population, n | Response rate, n (%) | Selected findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Documentation of family history information | Knowledge to identify HBOC or Lynch syndrome | Awareness of genetic services | Referral patterns | |||||

| Cox et al. [37] | USA | Cross- sectional | 2506 primary care physicians, naturopaths, obstetric gynecologists, gastroenterologists, oncologists, colorectal and general surgeons | 1242 (57) | Not assessed. | Indirectly assessed – knowledge was measured as confidence level. | Not assessed. | The most common reason for ordering/recommending BRCA or MMR testing was that the patient met practice guidelines, and in response to patients’ requests. Primary care physicians and obstetric gynecologists would order or recommend a patient with cancer to a genetic specialist for BRCA testing more frequently than MMR testing. |

| Prochniak et al. [38] | USA | Cross-sectional | Gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons, total not specified | 298 (~4% gastroenterologists and 6.5% surgeons in the USA) | Not assessed. | >90% could identify high risk colorectal cancer patients, but 70% was unable to stratify patients into high, moderate and low-risk categories. | Not assessed. | 83% referred patients for cancer genetic counseling; 80% ordered genetic testing for Lynch syndrome. No difference in referral rates or ordering of testing between specialties. Surgeons were more likely than gastroenterologists to refer high-risk patients to clinical medical geneticists or genetic counselors with expertise in cancer genetics (p=0.0007). |

| Bellcross et al. [39] | USA | Cross-sectional | 3115 family physicians, internists, pediatricians, and obstetric gynecologists | 1500 (48) | Not assessed. | 19% could identify low-risk and high risk patients correctly. | Indirectly assessed – 87% were aware of BRCA testing. | 25% ordered BRCA1/2 testing for at least one patient in the past year. Young female obstetric gynecologists who saw ≥ 100 patients and have been in practice ≤ 10 (p<0.001) years were most likely to be aware of testing. |

| Claybrook et al. [30] | USA | Cross-sectional | 151 oncologists | 60 (40) | Not assessed – although family history of colorectal cancer was cited to be a determining factor for referral. | Not assessed. | 83% were aware of a centre that offered genetic services for colorectal cancer. | 58% referred patients for genetic services in the past. 74% had referred due to patients’ requests for genetic services. |

| Vig et al. [17] | USA | Cross-sectional | 24,066 family physicians, internist and obstetric gynecologists | 860 (4) | 81% assessed history of cancers by initial intake form; 55% recorded family history of first-degree relatives only, and 33% recorded a full three-generation pedigree for risk assessment. | Not assessed. | Not assessed – although 76% referred when access to genetic counselor is within 10 miles. | 54% referred patients to genetic specialists, of which 53% referred due to patients’ requests. Obstetric gynecologists, female gender, and access to a genetic counselor were significant independent predictors for referral to genetic specialists. Use of family history or risk assessment tools was associated with increased referral (p<0.0005). |

| Kelly et al. [34] | USA | Cross-sectional | 440 rural primary care physicians | 176 (40) | Indirectly assessed – 76% used some form of family history collection, but 92% did not use a three-generation pedigree. Use of three-generation pedigree was associated with confidence (OR 3.25, 95%CI 1.38-7.67). | 70% could identify BRCA1/2-relevant scenario; 49% could identify Lynch-relevant scenario. | 66% reported access to medical geneticists was somewhat or extremely difficult. | For each unit improvement in access and knowledge, physicians had 1.69 (95%CI 1.17-2.43, p=.005) and 1.41 (95%CI 1.17-1.71, p<.001) times higher odds of using genetic testing. Higher knowledge and confidence were associated with higher odds of correctly identifying both hereditary cancer syndromes. Recent graduates were 1.37 (95%CI1.15-1.64) times more likely to accurately identify BRCA1/2 scenario. Lack of genetic testing does not appear to be due to differences in family history collection or ability to identify a hereditary cancer syndrome. |

| Domanska et al. [40] | Sweden | Cross-sectional | 103 gynecologists, oncologists and surgeons | 102 (99) | Not assessed. | 30% could identify the risk to inherit a Lynch-syndrome predisposing mutation. 45% could identify risk correctly for colorectal cancer, 18% for endometrial cancer, 43% for ovarian cancer, 39% for gastric cancer and 54% for urothelial cancer. | Not assessed. | Not assessed. |

| White et al. [9] | USA | Cross-sectional | 1035 family physicians | 284 (27) | Indirectly assessed – most family physicians regarded the patient’s sister’s age at diagnosis as an important factor in their referral decision. | Indirectly assessed – a hypothetical low-risk breast cancer patient presented to family physicians for assessment, and most regarded her risk of having a genetic mutation as relatively low. | Not assessed. | 92% would refer the patient for genetic services, and 50% would refer for genetic counseling. 13% would refer for genetic testing as patient requested. |

| Carroll et al. [41] | Canada | Cross-sectional | 3,990 family physicians, oncologists, gynecologists, gastroenterologists, general surgeons | 1427 (49) | Indirectly assessed – confidence in assessing risk of hereditary breast and colorectal cancers were associated with use of genetic services. | Indirectly assessed – confidence in referral criteria for both hereditary breast and colorectal cancer. | 91% of all physicians were aware of genetic testing for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer but only 60% for colorectal cancer. 75% of physicians know where to refer patients for genetic services. Awareness of genetic testing for colorectal cancer was lower compared to genetic testing for breast-ovarian cancer and significantly different among physician groups, with surgical oncologists and gastroenterologists reporting greatest awareness (p<0.001). Female were more likely than male to report awareness of the hereditary breast-ovarian cancer service (OR 2.9, 95%CI 1.9-4.6). | Oncologists referred the most. Physicians who could identify risk of hereditary breast and hereditary colorectal cancer were more likely to refer (OR 2.1 95%CI 1.6-2.7 and OR 1.5 95%CI 1.2-1.9, respectively). Physicians were also more likely to refer when they are: aware of the availability of genetic services for hereditary breast cancer (OR 4.8, 95%CI 3.2-7.3) or for hereditary colorectal cancer services (OR 1.9, 95%CI 1.5-2.4), knowledge of where to refer patients (OR 11.9, 95%CI 8.8-16.2), more confident in knowledge of referral criteria for hereditary breast cancer (OR 4.1 (95%CI 3.1-5.4) and hereditary colorectal cancer (OR 2.7 (95%CI 2.0-3.6), and higher confidence in obtaining family history (OR 1.5 95%CI 1.2-1.9). |

| Brandt et al. [18] | USA | Cross-sectional | 243 primary care physicians, gynecologists, oncologists, surgeons | 82 (34) | 95% inquired about first-degree relatives, 77% asked about second-degree relatives, 66% asked about cancer history on both the maternal and paternal sides of the family. | Indirectly assessed – knowledge was measured by comfort score. PCP was significantly less comfortable with identifying patients for referral and with discussing genetics than specialists. | 59% were aware of hospital’s cancer genetics program, with specialists being more aware than PCPs (p<0.0001) | 73% referred patients based on patient request; 54% did not refer due to patient disinterest. Patient referral was based on family history of cancer (96%), patient cancer history (83%), and patient request(73%). |

| Tomatir et al. [32] | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 100 primary care physicians | 60 (60) | Indirectly assessed – 21% were able to develop a family tree by learning the genetic history of individuals. | 29% knew about autosomal dominant disorders. | 27% were aware of local genetic centers; 7% were knowledgeable about genetic consultation and testing. | Not assessed. |

| Wideroff et al.[42] | USA | Cross-sectional | 2079 primary care physicians, obstetrics gynecologists, gastroenterologists, oncologists, urologists and general surgeons | 1251 (71) | Not assessed. | 38% could identify autosomal dominant inheritance for BRCA1/2 mutations, 34% could also identify that BRCA1/2 mutations occur in <10% of breast cancer patients. Only 13% could identify HNPCC gene penetrance as ≥50%. | 61% were aware of BRCA testing – highest among gynecologists and lowest among gastroenterologists; 23% were aware of HNPCC genetic testing – highest among gastroenterologists and lowest among general practitioners. | 41% who were unsure of paternal inheritance of BRCA1/2 vs. 45% who could identify the paternal inheritance of BRCA1/2 mutations would refer the patient elsewhere for testing or risk assessment; 46% who were not sure of the risk of HNPCC referred patients elsewhere for testing or risk assessment vs. 15% who could identify the risk of HNPCC. Oncologists, obstetric gynecologists and general surgeons were more knowledgeable about breast/ovarian cancer genetics and cancer risk assessment than primary care physicians; as were gastroenterologists to the HNPCC questions. |

| McCann et al.[43] | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 1079 general practitioners | 541 (50) | Not assessed – although 87% agreed on their role in taking a family history. | 60% could identify an individual with increased risk for colorectal cancer, and 87% for breast cancer. | Not assessed. | Low referrals, but obstetric gynecologists had referred patients to clinical genetics the most. Given the high-risk colorectal cancer patient, 70% would refer the patient to a surgical clinic vs. 59% to a genetics clinic. Given the high-risk breast cancer patient, 85% would refer the patient to a genetics clinic vs. 68% to a mammography clinic. Female physicians were also more likely to refer high-risk breast cancer patient to a genetics clinic than male physicians (p<0.001). |

| Acheson et al.[36] | USA | Cross-sectional | 498 family physicians | 190 (38) | Not assessed. | Indirectly assessed – ≥79% claimed to have addressed genetic aspects of familial breast-ovarian, colon/endometrial or other cancers. | 24% said that genetic consultation is very difficult to obtain or unavailable; 31% of rural and suburban practitioners said face-to-face genetic consultation was very difficult or unavailable. | The most common referrals to a geneticist were for genetic assessment of a family history of breast-ovarian cancer (13%) and family history of colon cancer (5%). Physician factors such as gender, year of graduation and practice setting were not associated with the frequency of addressing genetic aspects of any groups of conditions. |

| Morgan et al.[44] | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | 586 general practitioners | 328 (56) | Not assessed. | Indirectly assessed – 32% were not sure the type of test for breast cancer. | 29% were not sure about access to genetic services. Distance, waiting time, and ability to contact genetic services were considered barriers by urban and rural physicians. 60% could identify the type of test for breast cancer. | 40% had referred a breast cancer patient or ordered a genetic test in the last year. |

| Wideroff et al.[20] | USA | Cross-sectional | 1763 primary care physicians, obstetric gynecologists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, urologists, and general surgeons | 1251 (71) | 37% very frequently ask patients about cancer in second-degree relatives, and 38% for the age of relatives' cancer diagnosis. | Not assessed. | 12% were unsure of availability of local testing and counseling services. | Use of genetic testing is lower when physicians are unsure of availability of local genetic services (OR 0.39, 95%CI 0.23-0.66). Use of genetic testing is highest when patients requested for it (OR 5.52, 95%CI 3.97-7.67). 27% referred patients elsewhere for genetic testing compared to 8% who ordered testing directly. |

| Welkenhuysen et al. [45] | Belgium | Cross-sectional | 356 general practitioners | 215 (60) | Not assessed. | >80% could identify high-risk patients and maternal inheritance pattern of breast cancer. Only 40% were able to identify the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of breast cancer. | 55% were aware of the availability of genetic testing for breast cancer. | Not assessed. |

| Sifri et al.[19] | USA | Cross-sectional | 726 primary care physicians | 475 (65) | 90% very frequently recorded first-degree family history; 38% ordered or referred for testing (p=0.21). 56% very frequently recorded second-degree family history; 38% ordered or referred for testing (p=0.45). 65% considered family history to be the best predictor of cancer for asymptomatic patients. | 16% could identify the risk of developing colorectal cancer in patients with MMR gene; 44% were uncertain about colorectal cancer risk for patients with MMR gene. | Not assessed. | 71% referred for cancer susceptibility testing; age and family history was reported the best predictors for cancer risk and referral. Physicians practicing in an integrated health system were more than twice as likely to use cancer susceptibility testing than those who were not affiliated to the system (OR 2.2, 95%CI 1.2-4.0). |

| Pichert et al.[46] | Switzerland | Cross-sectional | 1391 primary care physicians, obstetric gynecologists, and oncologists | 628 (45) | Not assessed. | 23% could identify the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of hereditary breast cancer. 74% could identify hereditary breast cancer by young age at onset. Knowledge of hereditary breast cancer was significantly correlated to younger age and specialty. | Not assessed. | Not assessed. |

| Mehnert et al.[33] | Germany | Cross-sectional | 529 gynecologists | 172 (33) | Indirectly assessed – 39% were confident with constructing a pedigree and 36% were confident with estimating cancer risk by pedigree analysis. | Indirectly assessed – 66% were confident with basic genetic knowledge. | Not assessed. | 34% referred patients for genetic counseling or genetic testing; 85% of which patients were referred to one of the university cancer centers, 14% to a geneticist, and 1% did not specify their referral. |

| Koil et al. [29] | USA | Cross-sectional | 855 primary care physicians, obstetric gynecologists, oncologists and general surgeons | 214 (25) | Not assessed. | Not assessed. | 12% did not know who to refer patients to, irrespective of practice location. | 51% referred patients for an indication of hereditary breast cancer. Female specialists and physicians graduating before 1990 were more likely to have ever referred. Urban- and suburban-practice physicians were twice as likely to have referred patients for genetic services as rural physicians. 87% referred based on family history of cancer. 48% would refer to a genetic counselor, 36% to an oncologist, 34% to a geneticist, and 13% to a surgeon. |

| Friedman et al. [53] | USA | Cross-sectional | 350 primary care physicians, obstetric gynecologists, general surgeons and pediatricians | 59 (17) | Not assessed. | Not assessed – although 59% have discussed breast cancer genetic screening with patients, 41% on ovarian cancer genetic screening, and 40% on colon cancer genetic screening. | 44% wanted to make a referral but no services were available. 64% indicated availability of genetic services as one of the barriers to genetic testing. | 39% referred patients for genetic evaluation for cancer risk. 76% would consider genetic screening for BRCA1/2 and 36% for HNPCC. 88% considered cost of genetic testing a barrier to use of genetic testing. |

| Freedman et al. [54] | USA | Cross-sectional | 1763 primary care physicians, obstetric gynecologists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, urologists, and general surgeons | 1251 (71) | Not assessed. | Not assessed. | 64% indicated that genetic testing was not readily available. 41% indicated genetic consultation was not readily available. | 38% referred patients for genetic testing; those who were unsure of availability of genetic testing facilities and were less likely to recommend genetic testing (OR 0.63, 95%CI 0.40-1.00). Oncologists reported feeling qualified to recommend genetic testing to their patients compared to primary care physicians (OR 6.28, 95%CI 3.77-10.48). |

| Doksum et al.[47] | USA | Cross-sectional | 2250 obstetric gynecologists, oncologists and internists | 803 (40) | Not assessed. | 93% of oncologists, 75% of obstetric gynecologists and 60% of internists could identify the autosomal inheritance pattern of hereditary breast cancer. | Not assessed – although oncologists were 3 times more likely to order BRCA testing for a patient if they have a genetic professional to whom they can refer patients to (OR 2.76, 95%CI 1.15-6.64). | Oncologists were more knowledgeable about cancer genetics and cancer risk assessment than primary care physicians, and had ordered a BRCA test either directly from a laboratory or through a genetic professional for a patient. |

| McCann et al.[48] | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 1079 general practitioners | 541 (50) | Not assessed – although 88% agreed that their role was taking a family history. | Indirectly assessed – male physicians were more dissatisfied with their genetic knowledge in breast and ovarian cancers than female physicians (p=0.001). | Not assessed. | Female general practitioners were more likely than males to feel confident in taking a family history and making referral decisions. |

| Batra et al.[21] | USA | Cross-sectional | 815 gastroenterologists | 258 (35) | 99% obtained a family history from their patient consisting of first-degree relatives (parents, siblings and children); 76% included second-degree relatives (grandparents, aunts and uncles) as part of the family history; 39% obtain a family history that includes first, second and more distant third-degree relatives. | 79% could identify a family history consistent with Lynch syndrome. | 95% were aware of cancer genetic consultation; 52% were aware of genetic testing for familial adenomatous polyposis but only 34% for Lynch syndrome. | 51% would refer to a genetic counselor prior to providing genetic testing, and 38% would send samples to a laboratory. Cost of testing was a concern for physicians when they refer patients. |

| Wilkins-Haug et al.[22] | USA | Cross-sectional | 1248 obstetric gynecologists | 564 (45) | 78% asked for patients’ family histories at initial visits. 24% do not routinely review family history at clinic visits. Physicians use family histories to assess the risk of breast cancer (95%), ovarian cancer (94%), and other cancers (87%). | Not assessed. | 93% were aware of genetic testing for breast cancer; 60% were aware of genetic testing for colon cancer, and 22% were not aware of genetic testing for colon cancer. | Not assessed. |

| Menasha et al.[49] 2000 | USA | Cross-sectional | 363 primary care physicians, oncologists, gastroenterologists, obstetric gynecologists, cardiologists, pulmonary medicine, geriatrics and neurologists | 89 (26) | Not assessed. | Indirectly assessed – 71% rated their knowledge of genetics and genetic testing as "fair" to "poor". | 77% were aware of the availability of genetic testing for breast cancer; 91% were aware of the existence of genetic consultation services; 71% were aware of the services available at major New York medical services. | 98% would refer a patient to a genetic counselor. |

| Escher & Sappino [50] | Switzerland | Cross-sectional | 400 primary care physicians, obstetric gynecologists and oncologists | 259 (65) | Not assessed. | 19% could identify the risk of developing breast cancer for BRCA mutation carriers; 45% could identify the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of breast cancer | Not assessed. | 98% would refer for genetic testing at patient’s request. |

| Acton et al.[23] | USA | Cross-sectional | 1148 primary care physicians, obstetric gynecologists, and internists | 254 (22) | 94% asked new patients about family history of cancer; 71% obtained family history of cancer for four generations, but were less likely to ask about children, aunts, uncles, great-aunts and uncles; 52% updated history annually or when a family member was discovered to have cancer; 46% discussed family history of cancer when the patient was diagnosed with cancer. | Not assessed. | Not assessed. | <20% had referred patients for genetic testing. Obstetric gynecologists referred more patients for cancer genetic testing than the others (p=0.008). |

| Fry et al.[31] | UK | Cross-sectional | 670 general practitioners | 397 (59) | Not assessed. | 53% overestimated the low-risk group as high-risk for breast cancer. 54% underestimated the high-risk group as moderate-risk group for colon cancer. | Not assessed. | 67% would refer high-risk patients to specialist genetic services; 58% for breast screening; 45% for other services. |

| Hayflick et al.[24] | USA | Cross-sectional | 4824 primary care physicians, family physicians, obstetric gynecologists, pediatricians, and internists | 1642 (34) | >95% routinely asked about family history of breast cancer; >80% asked about ovarian cancer. When family history of breast or ovarian cancer was identified, 80% of internists and obstetric gynecologists completed a 2- or 3-generation pedigree. | Not assessed. | 25% of internists did not know if genetic consultation was available; 15% of internists knew of no available services and reported no need for additional genetic services. | 3% of internists and 27% of obstetric gynecologists would refer patients for genetic counseling; 20% of both groups to other consultant. The most common reason for referral for genetic services was patient’s interest. Family physicians and obstetric gynecologists usually referred patients for prenatal genetic screening. |

| Friedman et al.[55] | USA | Cross-sectional | 350 primary care physicians, obstetric gynecologists, general surgeons and pediatricians | 101 (30) | Not assessed. | Not assessed – although 29% have discussed breast cancer genetic screening with patients, 19% on ovarian cancer genetic screening, and 16% on colon cancer genetic screening | 30% wanted to make a referral but no services were available. Unavailability of genetic testing (55%) and genetic counseling (46%) were considered barriers to genetic testing. | 19% had referred a patient for genetic services. 64% would consider BRCA1/2 genetic screening for patients and 31% for HNPCC. 69% considered cost of genetic testing a barrier to use of genetic testing. |

| Rowley et al.[51] | USA | Cross-sectional | 124 obstetric gynecologists | 64 (56) | Not assessed. | 61% could identify the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern as features of breast cancer; 79% could identify ovarian cancer as the type of tumor commonly found in families with breast cancer; only 36% recognized multiple primary breast cancers as a feature. | Not assessed. | Not assessed. |

| Singh et al.[8] | USA | Chart review | 499 colorectal cancer patients | Not applicable. | 55% of patients with family history of some type of cancer were recorded; 32% family history was absent; 8% had no available documentation regarding cancer; 5% of patients were uncertain of family history; 56% age of affected first-degree relative undocumented; 71% age of affected second-degree relative undocumented. | Not assessed. | Not assessed. | 7% of patients who met the revised Bethesda guidelines were referred for genetic evaluation |

| Murff et al.[25] | USA | Chart review | 995 patients at high risk for colon and breast cancer | Not applicable | 679 (68%) had some form of family history of cancer recorded. 62% documented the affected individuals. 39% recorded age at diagnosis of first-degree relatives’ vs. 16% of second-degree relatives. 79% recorded age at diagnosis of first-degree relatives with colon cancer, 61% recorded age at diagnosis of first-degree relatives with breast cancer, 60% recorded age at diagnosis of first-degree relatives with ovarian cancer, and only 4% recorded age at diagnosis of first-degree relatives with Lynch-associated cancers. | Indirectly assessed – 2 patients had ≥3 relatives with Lynch-associated cancers were not referred, and only 5 of 6 patients who met criteria for referral for early-onset breast cancer (BRCA1) was not referred for genetic services. | Not assessed. | Only 17% of individuals who meet criteria for early onset breast cancer genetic testing were referred for genetic services. |

| Grover et al.[26] | USA | Chart review | 387 colorectal cancer patients | Not applicable. | 97% documented some sort of family history. 59% documented a comprehensive family history for patients with a first- or second-degree relative with cancer; the accuracy of family history collected decreased with increasing number of cancers per family (p<0.0001). | Indirectly assessed – only 17% (13/75) patients who had personal or family histories that met the Bethesda criteria were referred for genetic assessment. | Not assessed. | Only 17% (13/75) of patients who had personal or family histories that met the Bethesda criteria were referred for genetic assessment. |

| Al-Habsi et al.[27] | UK | Mixed-method | 54 general practitioners | 36 (64) | 39% would initiate discussion if they knew patients had a significant family history of cancer; 53% asked about the diagnosis or type of cancer when consulted by asymptomatic patients, 50% asked about the age of onset of cancer; 44% asked about who was affected; 33% asked about the number of affected relatives. Physicians lack confidence in taking family history details, and did not know the right type of information to collect. | Lack of knowledge in genetics cited as one of the reasons for not taking a proper family history. | 92% did not know, or know very little, about their local genetics centre and the services it provided. | 69% would usually refer patients to a diagnostic clinic; 31% would usually refer patients to a genetics clinic. 89% patients initiated the discussion of family history of cancer which led to a genetic referral. Direct referral to the genetics clinic was made if the patient requested the referral. Referral was also determined by the type of cancer in the family history. |

| Mountcastle-Shah and Holtzman[56] | USA | Mixed-method | 994 primary care physicians, obstetric gynecologists, and pediatricians invited for semi-structured interviews; 752 invited for survey | 222 (22) responded, only 60 were interviewed; 100 (13) for survey | Not assessed. | Not assessed. | 90% were aware of genetic testing for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. | 35% interviewees had either ordered or referred a patient for BRCA testing. Obstetricians were the most likely to refer compared to family physicians. Patient interest |

| Burke et al.[28] | USA | Observational -unannounced standardized patient | 637 family physicians and internists | 86 (14) | 48% collected sufficient family history to assess breast cancer risk from a moderate risk patient; 100% from a strong maternal family history of breast cancer; 45% from a strong paternal family history of breast-ovarian cancer. | 60% could identify moderate risk patients; >70% could identify high risk patients but degree not specified. | Not assessed. | Referral for moderate risk, high risk (maternal), high risk (paternal) to a medical geneticist: 24%, 29%, and 9%, respectively. Referral for moderate risk, high risk (maternal), high risk (paternal) to non-geneticist: 0%, 46%, and 9%, respectively. |

| Carroll et al.[52] | Canada | Qualitative | 40 rural and urban family physicians | 40 (100) | Not assessed – although physicians thought they play an important role in cancer risk assessment. | Physicians indicated lack of knowledge about hereditary cancer and the indications for genetic testing. | Not assessed. | An average of 2 patients were referred to familial cancer clinics in the last year |

Table 1: Table of evidence of reviewed studies

Lack of detail and accuracy in family history of cancer documented by physicians

Eighteen studies covered this topic, including 13 cross-sectional studies [17-24], 3 chart reviews [8,25,26], 1 mixed-method study [27] and 1 observational study [28]. In general, physicians identify family history of cancer as the primary reason for referring a patient for genetic risk assessment. Despite the recognition, family history information tends to be under-collected in clinical practice [18,29,30]. Consistent with previous reviews and studies, only a small proportion of physicians frequently ask patients for the age and type of cancer diagnosed in the affected relative(s) when a family history of cancer is noted [8,18,20,25-28]. Family history information collected was also less accurate when the complexity of family history documentation increases with the number of cancers in the family [26].

Several other studies reported physicians’ lack of skill and confidence in constructing a three-generation pedigree or estimating risk by pedigree analysis [31-33]. Physicians who were confident were three times more likely to collect family history information using a three-generation pedigree for risk assessment [34].

Lack of time was also considered a barrier for comprehensive family history collection [15,23,35]. In an observational study of 138 primary care physicians in the United States, Acheson and colleagues found that physicians spent less than 2.5 minutes on discussing family history with patients, and that discussion took place more often during preventive care consultations rather than visits due to illness [36].

Poor identification of hereditary cancer, particularly Lynch syndrome

Twenty-nine studies investigated the identification of hereditary cancer, including 24 cross-sectional studies [9,18-21,31-34,36-51] 2 chart reviews [25,26], 1 observational study [28], 1 mixed method [27], and 1 qualitative study [52]. Overall, physicians demonstrated insufficient knowledge of hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and Lynch syndrome. Physicians lack knowledge about inheritance [21,32,38,42,45-47,50,51] and were less able to discriminate between low and high-risk patients [9,28,31,38,39]. Their competence in distinguishing hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and Lynch syndrome was dependent upon their specialty [34,42,43,46]. General practitioners and gynecologists were reported to be more competent in identifying hereditary breast-ovarian cancer patients than Lynch syndrome patients [31-34,42,43]. Consistent with the historical understanding that colorectal cancer is the hallmark cancer associated with Lynch syndrome, gastroenterologists were the most competent in identifying individuals with a family history consistent with hereditary colorectal cancer for genetic services compared to other physicians [19,41,42]. Findings from a single study from Sweden further suggest that physicians were unfamiliar with various Lynch-associated cancer risks, with more than half of the physicians underestimating the risk of colorectal and endometrial cancers [40].

Physicians’ knowledge of hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and Lynch syndromes were indirectly assessed by exploring their satisfaction, confidence and comfort level in identifying patients for genetic referral [9,18,33,37,41,48,49]. Physicians with greater knowledge of hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and Lynch syndromes had higher levels of confidence and were therefore more comfortable with identifying patients for referral [34,41].

Low awareness of local genetic providers leads to low access of genetic services

Nineteen cross-sectional studies [18,20-22,24-29,30,32,34,36,39,41,42,44,45,49,53-55] and two mixed-method studies [27,56] were identified for this topic. Several studies have shown that physicians were more likely to refer a patient directly to a clinical genetics service when they were aware of such service [20,24,29,44], and if such service was available at close proximity [17,20,30,41], Unfortunately, our review shows that many physicians did not know or knew very little about the availability of their local genetic centre and the services it provided [18,20,24,27,30,32,41,45,54,55]. Physicians were also less aware of the availability of genetic testing for Lynch syndrome compared to hereditary breast-ovarian cancer or familial adenomatous polyposis [18,21,41,42].

Access to a clinical genetics service, such as obtaining an appointment for consultation with a geneticist was considered to be a challenge by primary care physicians, especially for those practicing in suburban and rural areas [34,36]. The lack of face-to-face genetic consultation and distance (such as travelling by car for more than two hours) to a genetic consultant, were indicated by rural and suburban physicians as challenges for making referrals [34,36,44]. Long waiting time for a genetic consultation was also a concern for urban, suburban and rural physicians in the United States and New Zealand [17,24,29,34,44].

While cost of genetic services was a concern for most North American physicians when referring patients [17,21,24,53-56], the concern was less often reported by physicians practicing outside the United States [44,57]. Although the cost of testing was considered a barrier to some extent by some physicians in Australia, they were more concerned about the lack of reimbursement by health insurance [57].

Referral patterns

Of the 41 studies reviewed, 29 studies examined physicians’ referral patterns. There was a high heterogeneity among studies of the referral factors investigated, but the most prominent factors were specialty, gender and years in practice since graduation. Specialists in general were more adept at referring patients for genetic services [17,41,43,56], as were female practitioners and recent graduates [34,41,48,50]. Other factors reported include physicians’ concern for patient’s family members, and to enhance risk assessment and medical management for patients [18,29]. Physicians with positive attitudes toward genetic services had more confidence in their knowledge about cancer genetics and the referral criteria; those who were more skilled in pedigree analysis and cancer risk assessment were also more likely to identify patients for referral [17,34,41]. Nevertheless, the chart reviews showed poor identification of patients appropriate for genetic referral [8,25,26].

Referral of patients with suspected hereditary breast-ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome was low in general. Physicians were more likely to refer a patient for genetic services when the patient initiated the discussion of family history, and requested for a referral [9,17,18,20,24,27,29,30,37,50]. Additionally, referral of patients for genetic testing varied depending on the type of cancer diagnosed in the family [18,27,43].

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to exclusively focus on referral of patients with suspected hereditary breast-ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome. Overall, our review highlights the need to improve cancer genetics education and family history documentation among health care providers, and increase awareness of genetic services. As most of the studies included in this review were of cross-sectional design and were North American origin, it is likely that the results from this review are more generalizable for clinical practice in North America. The current study also found ‘referral for genetic services’ was infrequently measured as an outcome variable. The lack of measures of association between referral and the potential barriers studied makes it difficult to compare the effects of the barriers on providers’ decisions to refer between studies. In addition, some studies reporting to assess barriers to ‘referral for genetic services’ did not measure the key component genetic counseling, but only focused on genetic testing aspects (‘use of genetic services’).

The current study focused on the hereditary cancer syndromes more commonly encountered in the clinical genetics setting (hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and Lynch syndrome), found physicians lack sufficient knowledge about genetics and lack of confidence in interpreting familial patterns of disease. These findings are similar to a recent broad literature review on the delivery of genetic services for common chronic adult diseases [14,15], but our detailed investigation highlights the scarcity of research investigating referral of women with suspected Lynch syndrome who may be at increased risk for developing endometrial cancer, or colorectal cancer after endometrial cancer [58,59]. Despite the growing recognition that women with mismatch repair gene mutations have equal if not higher risk of developing endometrial cancer than colorectal cancer [59,60], physicians underestimated the risk of Lynch-associated endometrial cancer and other extracolonic cancers [40]. Reduced awareness of Lynchassociated cancers may consequently lead to reduced identification and patient referral. Hence, increased efforts to educate physicians about both Lynch-associated extracolonic cancers, and other hereditary cancer syndromes, may increase physicians’ knowledge and confidence, thereby increasing patient referrals and improving patient outcomes. There is also a paucity of research on the ability of physicians in care of women (e.g. gynecologists) to identify and subsequently refer possible mismatch repair gene mutation carriers for genetic services, as well as studies to compare the genetic counseling provided by non-genetic specialists versus genetic specialists to improve patient outcomes. Further controlled studies are required to provide evidence-base in these areas.

Although family history is a relatively simple clinically relevant tool for targeted screening and interventions for individuals at increased risk of cancer, our review shows that family history documentation is underutilized in clinical practice. Consistent with findings from previous reviews, physicians’ family history documentation was inadequate, and when recorded often lacks details and completeness [61,62]. Since time constraints and lack of genetic knowledge were cited as barriers to collect family history, [27,35,44] a computerized family history system could be implemented in the clinical setting to aid family history collection [63]. Such systems have demonstrated to be effective and convenient in collecting family history information in a clinical setting, and have been recently implemented at two primary care clinics [63]. Where relevant, results from tumor testing in combination with family history should be used to improve identification and referral of patients with suspected hereditary cancer syndromes [64-66]. Future possibilities would be to incorporate built-in decision support software to prompt physicians when a genetic referral is warranted. However, decision tools are complex interventions [67], and development of such tools should take into account possible variation in service type across different jurisdictions, and should consider whether the evidence base identified is relevant to their own setting.

Physicians limited knowledge of genetic services might reflect physicians’ infrequent use of genetic services due to infrequent contact with patients with hereditary cancer syndromes and other inherited conditions [44]. In the hospital setting, multidisciplinary teams consisting of genetic and non-genetic health professionals have been proposed, or are in place, to address the changing landscape of genetic health care [68], although the effectiveness of multidisciplinary team meetings in improving patient outcomes is not yet proven. The roles assigned for each specialist and the various types of liaison planned may forge new relationships and promote discussion between non-genetic and genetic professionals regarding treatment and management options for high-risk patients [68]. Such multidisciplinary team meetings may facilitate and simplify a referral process, and reduce waiting times for patients who are eligible for genetic consultation and/or testing. It may be necessary to have a coordinator with an appropriate genetic background to act as contact point for physicians, and patients, and to manage eligible patients through the various phases of care that may span different centers. However, implementation of multidisciplinary teams in cancer services can be difficult as health services vary across jurisdictions; randomized trials should be considered to investigate the feasibility and effectiveness of such multidisciplinary meetings. Implementation of a multidisciplinary meeting may be even more difficult to establish in rural areas due to lack of health professionals and available specialist cancer or genetic services, and might be a challenge due to time constraints. Although further development of telehealth would assist this [36], there would be challenges coordinating such a system given clinical genetics services in some areas serve an entire state. Moreover, high-risk individuals may seek advice or be identified in the general practice or specialist care setting, which would not be captured by hospital-based multidisciplinary meetings. Clear referral guidelines for both hospital and other clinical settings would thus assist in providing relevant information for triage of patients with suspected hereditary cancer to genetic specialists for genetic consultation and risk-appropriate care [55,69,70].

There are some limitations to this study. While other care models for genetic services that do not involve referral to genetic specialists exist, we did not assess these under the assumption that, as for other specialist services provided to cancer patients, genetic specialists is likely to provide the most optimal and comprehensive care for patients with suspected hereditary cancer. In addition, vast majority of studies included in this review were of cross-sectional design; it would be beneficial to conduct interventional studies to better assess referral based on physician knowledge and skills relating to factors important for referral of patients for cancer genetic services.

Conclusion

This review highlights the need for research into improving referral of high-risk individuals and their family members for genetic services. More educational efforts are needed for hereditary cancers, particularly for Lynch syndrome. Clear referral guidelines and integration of a computerized family history tool with a built-in decision support to prompt physicians when a referral is warranted may improve referral of possible mutation carriers for genetic services. Increased collaboration among general practitioners, specialists and medical genetic specialists may also improve referral and clinical management of at-risk patients, and their family members, who would ultimately benefit from a genetic consultation or testing.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Lars Eriksson, health sciences librarian, for his assistance with the literature search.

References

- Garber JE, Offit K (2005) Hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes. J Clin Oncol 23: 276-292.

- Vasen HF, Blanco I, Aktan-Collan K, Gopie JP, Alonso A, et al. (2013) Revised guidelines for the clinical management of Lynch syndrome (HNPCC): recommendations by a group of European experts. Gut 62: 812-823.

- Järvinen HJ, Aarnio M, Mustonen H, Aktan-Collan K, Aaltonen LA, et al. (2000) Controlled 15-year trial on screening for colorectal cancer in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 118: 829-834.

- Järvinen HJ, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Aktán-Collán K, Peltomäki P, Aaltonen LA, et al. (2009) Ten years after mutation testing for Lynch syndrome: cancer incidence and outcome in mutation-positive and mutation-negative family members. J Clin Oncol 27: 4793-4797.

- Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen LM, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, et al. (2006) Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med 354: 261-269.

- Lu KH, Loose DS, Yates MS, Nogueras-Gonzalez GM, Munsell MF, et al. (2013) Prospective, multi-center randomized intermediate biomarker study of oral contraceptive vs. depo-provera for prevention of endometrial cancer in women with Lynch Syndrome. Cancer Prev Res 0020.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2006) Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 73: 869-874.

- Singh H, Schiesser R, Anand G, Richardson PA, El-Serag HB (2010) Underdiagnosis of Lynch syndrome involves more than family history criteria. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 8: 523-529.

- White DB, Bonham VL, Jenkins J, Stevens N, McBride CM (2008) Too many referrals of low-risk women for BRCA1/2 genetic services by family physicians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17: 2980-2986.

- Sweet KM, Bradley TL, Westman JA (2002) Identification and referral of families at high risk for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 20: 528-537.

- Wong C, Gibbs P, Johns J, Jones I, Faragher I, et al. (2008) Value of database linkage: are patients at risk of familial colorectal cancer being referred for genetic counselling and testing? Intern Med J 38: 328-333.

- Schofield L, Grieu F, Goldblatt J, Amanuel B, Iacopetta B (2012) A state-wide population-based program for detection of lynch syndrome based upon immunohistochemical and molecular testing of colorectal tumours. Fam Cancer 11: 1-6.

- Tan YY, McGaughran J, Ferguson K, Walsh MD, Buchanan DD, et al. (2013) Improving identification of lynch syndrome patients: a comparison of research data with clinical records. Int J Cancer 132: 2876-2883.

- Scheuner MT, Sieverding P, Shekelle PG (2008) Delivery of genomic medicine for common chronic adult diseases: a systematic review. JAMA 299: 1320-1334.

- Suther S, Goodson P (2003) Barriers to the provision of genetic services by primary care physicians: a systematic review of the literature. Genet Med 5: 70-76.

- Qureshi N, Wilson B, Santaguida P, Carroll J, Allanson J, et al. (2007) Collection and use of cancer family history in primary care. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) : 1-84.

- Vig HS, Armstrong J, Egleston BL, Mazar C, Toscano M, et al. (2009) Cancer genetic risk assessment and referral patterns in primary care. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 13: 735-741.

- Brandt R, Ali Z, Sabel A, McHugh T, Gilman P (2008) Cancer genetics evaluation: barriers to and improvements for referral. Genet Test 12: 9-12.

- Sifri R, Myers R, Hyslop T, Turner B, Cocroft J, et al. (2003) Use of cancer susceptibility testing among primary care physicians. Clin Genet 64: 355-360.

- Wideroff L, Freedman AN, Olson L, Klabunde CN, Davis W, et al. (2003) Physician use of genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: results of a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12: 295-303.

- Batra S, Valdimarsdottir H, McGovern M, Itzkowitz S, Brown K (2002) Awareness of genetic testing for colorectal cancer predisposition among specialists in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol 97: 729-733.

- Wilkins-Haug L, Erickson K, Hill L, Power M, Holzman GB, et al. (2000) Obstetrician-gynecologists' opinions and attitudes on the role of genetics in women's health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 9: 873-879.

- Acton RT, Burst NM, Casebeer L, Ferguson SM, Greene P, et al. (2000) Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of Alabama's primary care physicians regarding cancer genetics. Acad Med 75: 850-852.

- Hayflick SJ, Eiff MP, Carpenter L, Steinberger J (1998) Primary care physicians' utilization and perceptions of genetics services. Genet Med 1: 13-21.

- Murff HJ, Byrne D, Syngal S (2004) Cancer risk assessment: quality and impact of the family history interview. Am J Prev Med 27: 239-245.

- Grover S, Stoffel EM, Bussone L, Tschoegl E, Syngal S (2004) Physician assessment of family cancer history and referral for genetic evaluation in colorectal cancer patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2: 813-819.

- Al-Habsi H, Lim JN, Chu CE, Hewison J (2008) Factors influencing the referrals in primary care of asymptomatic patients with a family history of cancer. Genet Med 10: 751-757.

- Burke W, Culver J, Pinsky L, Hall S, Reynolds SE, et al. (2009) Genetic assessment of breast cancer risk in primary care practice. Am J Med Genet A 149A: 349-356.

- Koil CE, Everett JN, Hoechstetter L, Ricer RE, Huelsman KM (2003) Differences in physician referral practices and attitudes regarding hereditary breast cancer by clinical practice location. Genet Med 5: 364-369.

- Claybrook J, Hunter C, Wetherill LF, Vance GH (2010) Referral patterns of Indiana oncologists for colorectal cancer genetic services. J Cancer Educ 25: 92-95.

- Fry A, Campbell H, Gudmunsdottir H, Rush R, Porteous M, et al. (1999) GPs' views on their role in cancer genetics services and current practice. Fam Pract 16: 468-474.

- Tomatir AG, Sorkun HC, Demirhan H, AkdaÄŸ B (2007) Genetics and genetic counseling: practices and opinions of primary care physicians in Turkey. Genet Med 9: 130-135.

- Mehnert A, Bergelt C, Koch U (2003) Knowledge and attitudes of gynecologists regarding genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Patient Educ Couns 49: 183-188.

- Kelly KM, Love MM, Pearce KA, Porter K, Barron MA, et al. (2009) Cancer risk assessment by rural and Appalachian family medicine physicians. J Rural Health 25: 372-377.

- Taylor MR, Edwards JG, Ku L (2006) Lost in transition: challenges in the expanding field of adult genetics. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 142C: 294-303.

- Acheson LS, Stange KC, Zyzanski S (2005) Clinical genetics issues encountered by family physicians. Genet Med 7: 501-508.

- Cox SL, Zlot AI, Silvey K, Elliott D, Horn T, et al. (2012) Patterns of cancer genetic testing: a randomized survey of Oregon clinicians. J Cancer Epidemiol 2012: 294730.

- Prochniak CF, Martin LJ, Miller EM, Knapke SC (2012) Barriers to and motivations for physician referral of patients to cancer genetics clinics. J Genet Couns 21: 305-325.

- Bellcross CA, Kolor K, Goddard KA, Coates RJ, Reyes M, et al. (2011) Awareness and utilization of BRCA1/2 testing among U.S. primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med 40: 61-66.

- Domanska K, Carlsson C, Bendahl PO, Nilbert M (2009) Knowledge about hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer; mutation carriers and physicians at equal levels. BMC Med Genet 10: 30.

- Carroll JC, Cappelli M, Miller F, Wilson BJ, Grunfeld E, et al. (2008) Genetic services for hereditary breast/ovarian and colorectal cancers - physicians' awareness, use and satisfaction. Community Genet 11: 43-51.

- Wideroff L, Vadaparampil ST, Greene MH, Taplin S, Olson L, et al. (2005) Hereditary breast/ovarian and colorectal cancer genetics knowledge in a national sample of US physicians. J Med Genet 42: 749-755.

- McCann S, MacAuley D, Barnett Y (2005) Genetic consultations in primary care: GPs' responses to three scenarios. Scand J Prim Health Care 23: 109-114.

- Morgan S, McLeod D, Kidd A, Langford B (2004) Genetic testing in New Zealand: the role of the general practitioner. N Z Med J 117: U1178.

- Welkenhuysen M, Evers-Kiebooms G. (2003) The reactions of general practitioners, nurses and midwives in Flanders concerning breast cancer risks in a high-risk situation. Community Genet. 6: 206-213.

- Pichert G, Dietrich D, Moosmann P, Zwahlen M, Stahel RA, et al. (2003) Swiss primary care physicians' knowledge, attitudes and perception towards genetic testing for hereditary breast cancer. Fam Cancer 2: 153-158.

- Doksum T, Bernhardt BA, Holtzman NA (2003) Does knowledge about the genetics of breast cancer differ between nongeneticist physicians who do or do not discuss or order BRCA testing? Genet Med 5: 99-105.

- McCann S, Macauley D, Barnett Y. (2002) General Practitioners and Genes Perceived Roles, Confidence and Satisfaction with Knowledge. The European Journal of General Practice. 8: 140-145.

- Menasha JD, Schechter C, Willner J (2000) Genetic testing: a physician's perspective. Mt Sinai J Med 67: 144-151.

- Escher M, Sappino AP (2000) Primary care physicians' knowledge and attitudes towards genetic testing for breast-ovarian cancer predisposition. Ann Oncol 11: 1131-1135.

- Rowley PT, Loader S (1996) Attitudes of obstetrician-gynecologists toward DNA testing for a genetic susceptibility to breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol 88: 611-615.

- Carroll JC, Brown JB, Blaine S, Glendon G, Pugh P, et al. (2003) Genetic susceptibility to cancer. Family physicians' experience. Can Fam Physician 49: 45-52.

- Friedman L, Cooper HP, Webb JA, Weinberg AD, Plon SE (2003) Primary care physicians' attitudes and practices regarding cancer genetics: a comparison of 2001 with 1996 survey results. J Cancer Educ 18: 91-94.

- Freedman AN, Wideroff L, Olson L, Davis W, Klabunde C, et al. (2003) US physicians' attitudes toward genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. Am J Med Genet A 120A: 63-71.

- Friedman LC, Plon SE, Cooper HP, Weinberg AD (1997) Cancer genetics--survey of primary care physicians' attitudes and practices. J Cancer Educ 12: 199-203.

- Mountcastle-Shah E, Holtzman NA (2000) Primary care physicians' perceptions of barriers to genetic testing and their willingness to participate in research. Am J Med Genet 94: 409-416.

- Bathurst L, Huang QR (2006) A qualitative study of GPs' views on modern genetics. Aust Fam Physician 35: 462-464.

- Win AK, Lindor NM, Winship I, Tucker KM, Buchanan DD, et al. (2013) Risks of colorectal and other cancers after endometrial cancer for women with Lynch syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst 105: 274-279.

- Win AK, Young JP, Lindor NM, Tucker KM, Ahnen DJ, et al. (2012) Colorectal and other cancer risks for carriers and noncarriers from families with a DNA mismatch repair gene mutation: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 30: 958-964.

- Pande M, Wei C, Chen J, Amos CI, Lynch PM, et al. (2012) Cancer spectrum in DNA mismatch repair gene mutation carriers: results from a hospital based Lynch syndrome registry. Fam Cancer 11: 441-447.

- Qureshi N, Wilson B, Santaguida P, Little J, Carroll J, et al. (2009) Family history and improving health. Evid Rep Technol Assess 186: 1-135.

- Wilson BJ, Qureshi N, Santaguida P, Little J, Carroll JC, et al. (2009) Systematic review: family history in risk assessment for common diseases. Ann Intern Med 151: 878-885.

- Orlando LA, Hauser ER, Christianson C, Powell KP, Buchanan AH, et al. (2011) Protocol for implementation of family health history collection and decision support into primary care using a computerized family health history system. BMC Health Serv Res 11: 264.

- Moreira L, Balaguer F, Lindor N, de la Chapelle A, Hampel H, et al. (2012) Identification of Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA 308: 1555-1565.

- Perez-C L, Ruiz PC, Guarinos C, Alenda C, Paya A, et al. (2011) Comparison between universal molecular screening for Lynch syndrome and revised Bethesda guidelines in a large population-based cohort of patients with colorectal cancer. Gut. 61: 865-872.

- Kwon JS, Scott JL, Gilks CB, Daniels MS, Sun CC, et al. (2011) Testing women with endometrial cancer to detect Lynch syndrome. J Clin Oncol 29: 2247-2252.

- Emery J (2005) The GRAIDS Trial: the development and evaluation of computer decision support for cancer genetic risk assessment in primary care. Ann Hum Biol 32: 218-227.

- Battista RN, Blancquaert I, Laberge AM, van Schendel N, Leduc N (2012) Genetics in health care: an overview of current and emerging models. Public Health Genomics 15: 34-45.

- Emery J, Watson E, Rose P, Andermann A (1999) A systematic review of the literature exploring the role of primary care in genetic services. Fam Pract 16: 426-445.

- Lucassen A, Watson E, Harcourt J, Rose P, O'Grady J (2001) Guidelines for referral to a regional genetics service: GPs respond by referring more appropriate cases. Fam Pract 18: 135-140.

--

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14836

- [From(publication date):

December-2013 - Oct 01, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10202

- PDF downloads : 4634