Research Article Open Access

Reducing Under-Five Mortality in India - A Review of Major Encumbrances and Suggestions for Progress

Niyi Awofeso1*and Anu Rammohan21School of Population Health, University of Western Australia, Australia

2School of Business, Discipline of Economics, University of Western Australia, Australia

- Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Niyi Awofeso

Professor, School of Population Health

University of Western Australia, M431

35 Stirling Highway, Crawley

WA 6009, Australia

Tel: +61864881282

Fax: +61864881188

E-mail: niyi.awofeso@uwa. edu.au

Received Date: December 05, 2011; Accepted Date: January 05, 2012; Published Date: January 07, 2012

Citation: Awofeso N, Rammohan A (2012) Reducing Under-Five Mortality in India – A Review of Major Encumbrances and Suggestions for Progress. J Community Med Health Edu 2:116. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000116

Copyright: © 2012 Awofeso N, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

About 128 million of India’s 1.2 billion populations are aged less than 5 years. India’s under-five mortality rate fell from 2.2 million (123/1000 live births) in 1990 to 1.726 million (63/1000 live birth) in 2010. Based on current trends, India is unlikely to meet the 67% reduction in under-five mortality rate by 2015, compared with 1990 baseline (i.e. less than 41/1000 live births), as stipulated in Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4, Target 4A. This article examines six major factors encumbering efforts to reduce India’s under-five mortality: poorly delivered antenatal and obstetric care; inadequacy of well-resourced birthing resources; weak immunisation programs, particularly for measles and pneumonia, inadequate prevention and treatment of pneumococcal infections, and; chronic childhood undernutrition. Initiatives to address these obstacles are suggested. The authors posit that a well-resourced and efficiently managed continuum of care approach operated within a strong Indian health system, extending from Pre-pregnancy, Pregnancy, Birth, Postnatal, and Childhood is more likely to accelerate progress towards sustainable reductions in India’s under- five mortality compared with the status quo. Particular emphasis should be focussed on improving child care during the neonatal period, given the rising proportion of under-five deaths as percentage of total deaths prior to age 5 years.

Keywords

India; Under-five mortality; Antenatal care; Birthing Services; Immunisation; Pneumonia; Nutrition

Introduction

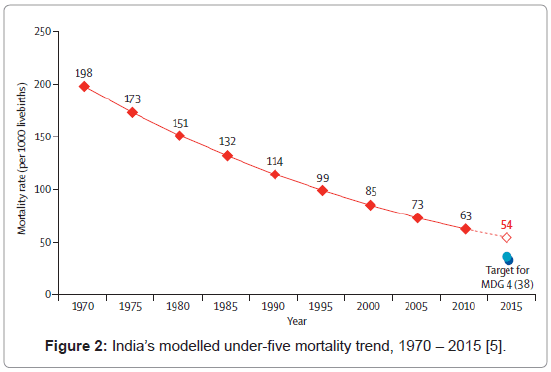

Under-5 mortality is the probability of dying between birth and fifth birthday. It is technically not a rate (i.e. the number of deaths divided by the number of population at risk during a certain period of time) but a probability of death derived from a life table and expressed as rate per 1,000 live births. Under-five mortality trends constitute a leading indicator of the level of child health and overall development in countries. It reliably reflects the impacts of complex health determinants such as high-risk fertility behaviour, poverty, gender equality, human resources for health, health infrastructure and service delivery effectiveness. Countries like China and Malaysia, which have addressed most of these determinants, have witnessed positive trends in child mortality [1-3]. In contrast, India’s under-five mortality rate is modeled to be 54/1000 live births by 2015 – 75% higher the global target of 32/1000 live births (Figure 1) [4]. Currently, one in every 15 children in India dies before reaching the age of five years – 1.726 million deaths annually. The average annual rate of reduction in underfive mortality in India between 1990 and 2006 has been 2.6%. If India is to reach the MDG Goal of 38 by 2015, the average annual rate of reduction in the next nine years has to be about 7.6 per cent (Figure 2) [5].

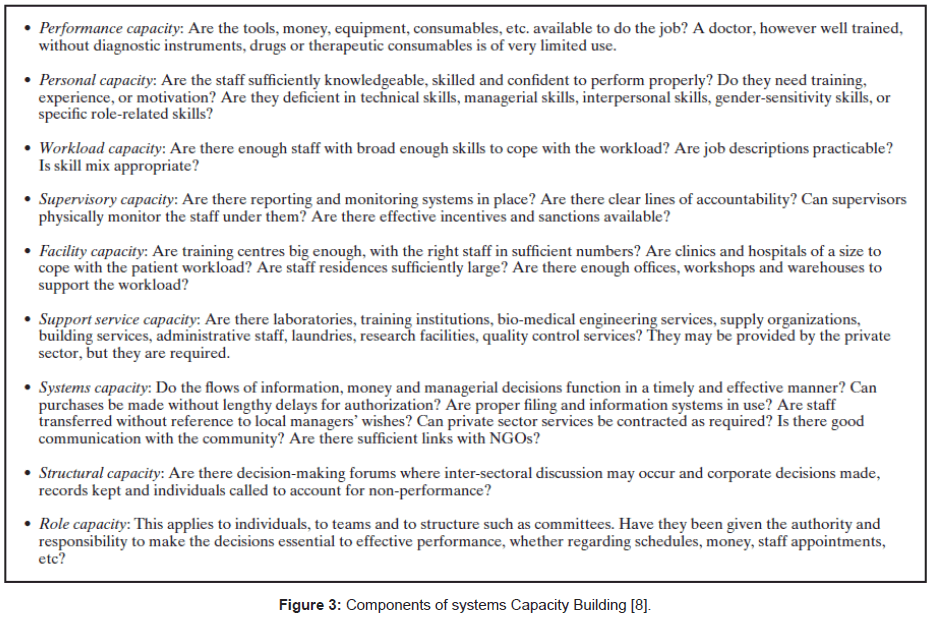

India’s rapid progress in relation to economic growth sharply contrasts with the slow pace in almost all areas of the health sector and in relation to social determinants of health such as absolute poverty rates, which fell modestly from 32% in 2004 to 32% in 2010 despite 9% annual economic growth in all but one year during this period. A major primary determinant of poor health progress in India is its health system functioning. In a 2004 study, Gupta et al. [6] found that although India’s health system has the administrative capacity to deliver its core public health functions, it was found to be deficient in health regulation and enforcement; health leadership capacity, and cultivating strong partnerships between all levels of government health departments, as well as with private health sector and civil society organisations. In its 2000 report, the World Health Organization ranked India 112 out of 190 nations in relation to health system performance [7]. Improving the functioning of India’s health system functioning is vital not just for reducing under-five mortality, but also for addressing other health priorities. Capacity building for improving India’s health system need to go beyond training health workers and include eight other components of systems capacity building (Figure 3) [8].

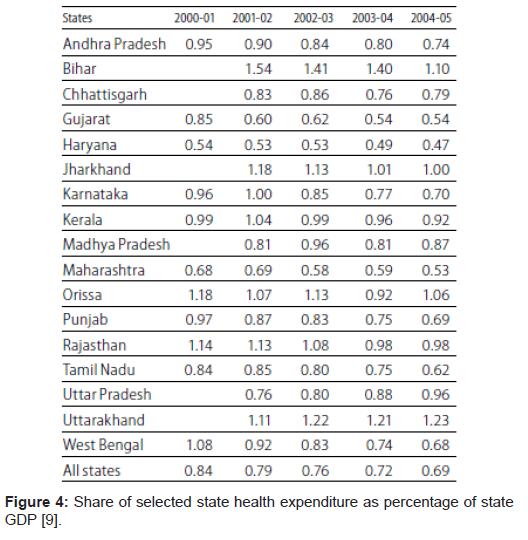

Funding and efficient management are two priorities in efforts to improve India’s health system. For example, Indian national government’s health expenditure as percentage of Gross Domestic Product declined from 1.12% in 2000 to 0.97% in 2005, but increased modestly to 1.05% of GDP in 2007. The health expenditure trends in India’s States are not much different from national trends (Figure 4). Indian state governments spent, on average 1% of their expenditure on health in 2004/2005, compared with 25% spent on health by Western Australia [9,10].

India’s under-five mortality trends vary in relation to gender, wealth quintile, residence and mothers’ education. Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2006 report, the under-five mortality for females in 2004 was 89/1000 live births, compared with 81/1000 live births for males. Under-five mortality was 141/1000 live births for the lowest wealth quintile, and 46/1000 live births for the highest wealth quintile. Under-five mortality was 111/1000 live births for rural-based infants and children, compared with 65/1000 live births for urbanbased children. Under-five mortality was 125/1000 live births for children of women with no formal education, compared with 51/1000 live births for children of women with post-secondary education [11]. The distribution of causes of death among Indian children aged underfive years was modeled in 2003 as; Diarrhea: 26.1%, Pneumonia: 27.7%; Malaria: 8%, Neonatal and other causes: 43.7% [12]. It is noteworthy that, in India, about 1 million under-five deaths – 30% of all neonatal deaths globally – occur during the neonatal period [5].

This article examines six core challenges to be addressed, apart from revitalising India’s health system, if the MDG under-five mortality target is to be achieved - poorly delivered antenatal and obstetric care; inadequacy of birthing resources; weak immunisation programs, particularly for measles, pneumococcal infections, and; chronic childhood undernutrition. Current status and strategies for improvement are discussed. Health systems’ strengthening is most efficiently addressed through the system’s capacity building framework discussed above. A promising partnership for health systems strengthening is the Model Districts Project – a joint initiative between the Earth Institute of Columbia University and India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The project’s strategy targets interventions and additional public health spending at the intersection of six building blocks of health system strengthening (i.e. financing, governance, supply chain management, health human resources, infrastructure and data management) and five areas along the continuum of care for mothers and children (i.e. antenatal care, safe delivery, immediate postnatal care, early childhood development and nutrition, and routine and sick child care) [13].

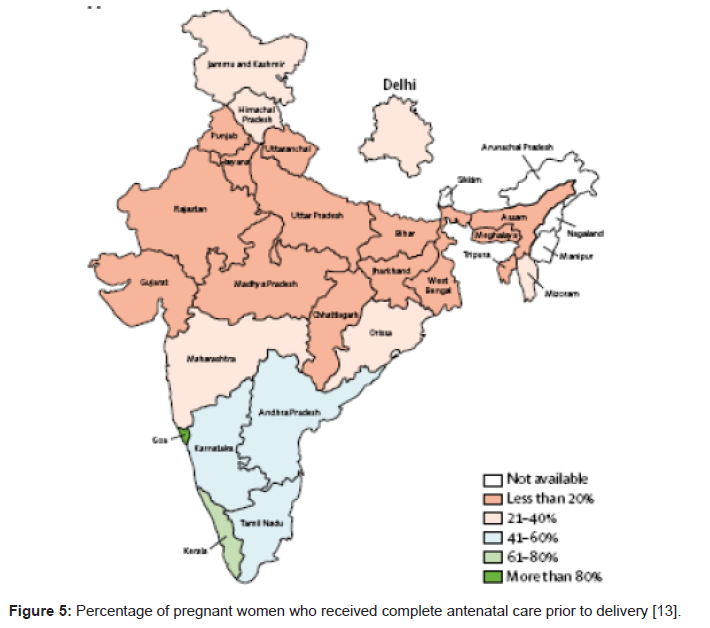

Improving India’s Antenatal and Obstetric Care Standards

Using indicators such as antenatal visits to qualified health professionals and well equipped health facilities, Puducherry, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Lakshadweep are classified as states with above 95% antenatal coverage. In contrast, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhard. Have less than 45% antenatal coverage [14]. The national rate of women who received complete antenatal care by skilled health professionals was 19%, with Goa and Kerala bucking the national trend with over 80% of pregnant women receiving complete antenatal care (Figure 5) [13].

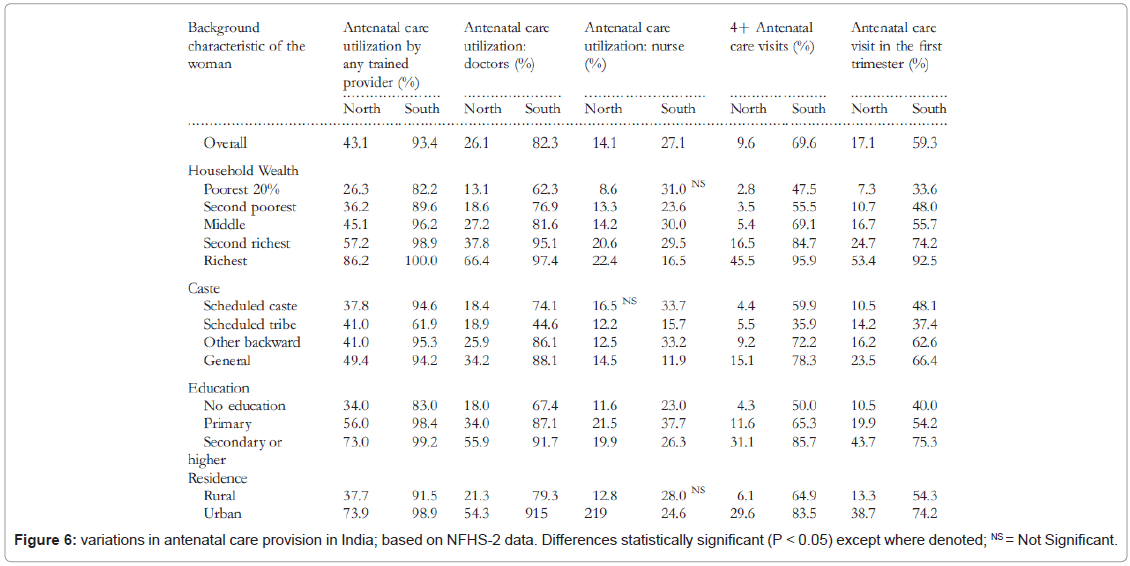

The content and quality of antenatal care and the availability of effective referral and essential obstetric care are important for antenatal care to be effective. Major differentials in antenatal care utilization within India, based on the results of India’s National Family Health Survey-2, are shown in Figure 6 [15].

Addressing antenatal care services implies first improving the quality of antenatal services available. Many antenatal services in India have been closed in recent years due to low patronage. Quality improvements of antenatal services should be comprehensive, ranging from culturally acceptable clinic architecture to competent staffs who attend clinics regularly. In a recent study of antenatal utilization in impoverished rural and tribal areas of a South Indian district, regular attendance by health care workers at clinics, and improved quality of health services were found to be associated with higher rates of antenatal services utilization, particularly in tribal areas [16].

Improving Birthing Resources

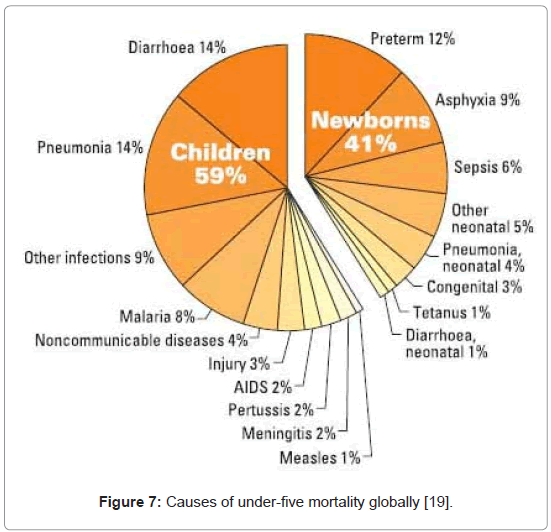

Well-resourced birthing facilities play a critical role in reducing perinatal, neonatal and maternal mortality, which are major contributors to India’s high under-five mortality. In 2009, the World Health Organization developed a Handbook of Emergency Obstetric Care to improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes [17]. As most deliveries in India take place outside of well-resourced and equipped birthing facilities, the neonatal mortality rate is likely to remain high until institutional births become the norm. In China, the promotion of institutional deliveries in urban areas have helped to reduce neonatal mortality, while it remains high in most rural areas where such facilities are inadequate [18]. Due to proportional increase in neonatal deaths as child deaths fell globally over the past two decades, neonatal deaths currently constitute 41% of all under-five mortality - of the 8.2 million under-five child deaths per year, about 3.3 million occur during the neonatal period. About 75% of all neonatal deaths occur in the first week of life, and 99% of all deaths occur in developing nations. Almost 58% of all under-five deaths in India currently occur during the neonatal period. Up to two thirds of newborn deaths can be prevented if known, effective birthing and other health measures are provided at birth and during the first week of life (Figure 7) [19].

Data from China’s National Maternal and Child Mortality Surveillance System suggest the apparent positive effect of China’s strategy to promote facility-based deliveries on reductions in neonatal mortality rate between 1996 and 2008 [20]. In India currently, only 47% of births are attended by skilled health professionals, compared with 99% in neighbouring Sri Lanka [13,21]. Effective care can reduce almost 70% of neonatal deaths: the package of essential care includes antenatal care for the mother, obstetric care and birth attendant’s ability to resuscitate newborns at birth. Most of the infection-related deaths could be avoided by treating maternal infections during pregnancy, ensuring a clean birth, care of the umbilical cord and immediate, exclusive breast-feeding. For infections, antibiotics are life-saving and need to be available locally. Low birth weight babies need to maintain body temperature through skin-to-skin contact with the mother. Several of the above interventions would also help save the lives of mothers and prevent stillbirths. These facilities generally need to be provided in well-equipped delivery centres. Given that most births are uneventful, non-clinic/hospital based deliveries should only be encouraged if referral facilities have been put in place to transport mothers and babies who experience complications. Given the extent of undernutrition in India, there is a high need for neonatologists and neonatal intensive care nurses to deliver parenteral nutrition and other intensive care for at-risk neonates.

Improving the Quality of Immunisation Programs

As at 2008, India accounted for 7.63 million (33%) of the 22.7 million infants and young children who missed receiving a first dose of measles vaccine through routine immunization services globally. It is estimated that 92,000 children die annually from measles and its complications in India annually. Measles immunisation coverage is one of the MDG targets. Coverage for the first dose of measles vaccination in all countries is expected to exceed that required for herd immunity, i.e. at least 94% coverage. India’s 2009 MDG progress report shows the following measles immunisation coverage trends [22] Table 1.

| Year | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCV coverage in target population (%) | 1 | 56 | 72 | 55 | 64 | 70 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 |

Table 1: Vaccine coverage for measles vaccination for children aged 1 year in India [22].

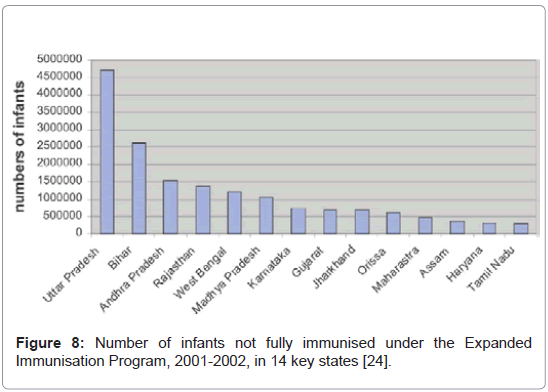

Similar trends are observable for other vaccine preventable diseases. In West Bengal, for example, a recently published study showed that only 54% of children in were covered for immunisation, ranging from 23% in Murshidabad to 72% in Hugli. Low rates of coverage were found among the vulnerable groups of poor minorities, especially in rural areas. No evidence of gender differences was found. Rising paternal and maternal educational levels were independently associated with likelihood of receiving the first dose of measles vaccine [23]. In 2008, only 32% of 1-year old children in Arunachal Pradesh received the first dose of measles vaccine, compared with 95.5% of Tamil Nadu 1-year olds. Nationally, measles coverage is broadly reflective of the adequacy of immunisation services as well as basic maternal and child health services (Figure 8) [24].

Addressing low immunisation coverage requires improvements in workforce quality, quantity and distribution, a more efficient health system, greater community communication about the benefits of vaccination, and improved vaccination surveillance especially among poor rural-based communities [25].

Prevention and Treatment of Pneumococcal Infections

Globally, pneumonia is responsible for 18% of under-five mortality. About 22% of all pneumococcal deaths in the under-five population occur during the neonatal period. More than 98% of deaths attributable to pneumococcal disease occur in developing countries. In 2005, the WHO estimated that pneumococcal disease caused approximately 1.6 million deaths, between 700,000 and 1 million of which were children under five years of age [26].

Seven pneumococcal serotypes - 1, 5, 6A, 6B, 14, 19F, 23F - were the most common globally; and based on year 2000 incidence and mortality estimates these seven serotypes accounted for 3,00,000 deaths in Africa and 2,00,000 deaths in Asia. Serotypes included in both the 10 and 13-valent PCVs accounted for 10 million cases and 6, 00,000 deaths worldwide. The serotypes included in existing PCV formulations account for 49%–88% of deaths in Africa and Asia where PD morbidity and mortality are the highest, but few children have access to these life-saving vaccines [27] in India, latest estimates indicate that about 1,42,000 children die of pneumococcal disease and haemophilus influenza B disease annually [28]. Since 2000, prevention of pneumococcal disease in young children has been possible by vaccination using multivalent glycoconjugate vaccines. The currently licensed 7 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV 7) contains 2 μg of capsular polysaccharides of serotypes 4, 9V, 14, 19F and 23F; 2 μg of oligosaccharide from 18C; and 4 μg of polysaccharide of serotype 6B in a 0.5 mL dose. The clinical efficacy of this vaccine was first demonstrated in a large-scale field study in the United States, where efficacy against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes of 97.4% (95% CI 82.7- 99.9) among children who received at least three doses (per-protocol analysis) was observed [29]. To date, pneumococcal vaccination is yet to be introduced in India, due to controversy over the efficacy of currently available vaccines [30]. No reliable data is available on pneumococcal treatment in India. However, Vaccination is perhaps the most efficient and cost effective method of reducing morbidity and mortality from treatable infectious diseases. The WHO Initiative for Vaccine Research remarked, “With the exception of water sanitation, no other modality – not even antibiotics – has had such a major effect on mortality reduction and population growth” [30]. Improved health systems infrastructure will make it feasible to treat children with established lung infection effectively.

Addressing Chronic Childhood Undernutrition

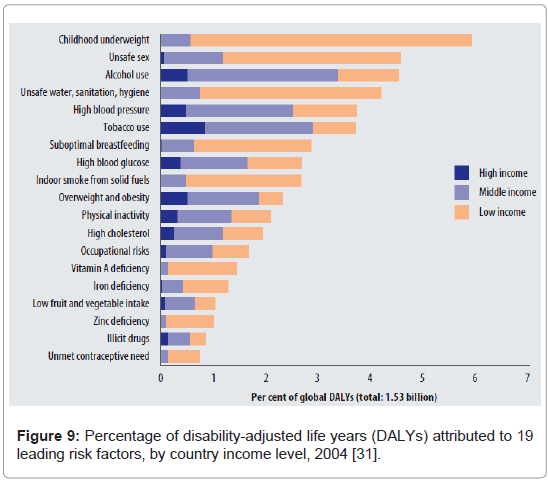

Childhood underweight is associated with the highest level of all Disability Adjusted Life Years, according to a2009 WHO Global health risks report (Figure 9) [31].

A WHO study showed that overall, 52.5% of all deaths in young children were attributable to undernutrition, varying from 44.8% for deaths because of measles to 60.7% for deaths because of diarrhoea. These findings underscore the need to make the improvement of the nutritional status of children a priority. In addition to reducing growth faltering, investments in child nutrition programs would support and complement disease-specific prevention and control programs in developing countries. In round numbers, this means that 10, 00,000 pneumonia deaths, 8, 00,000 diarrhoea deaths, 5, 00,000 malaria deaths, and 2,50,000 measles deaths could be prevented by eradication of child undernutrition [32].

Programmatic management of nutrition programs have been suboptimal. For example, India’s integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) program is one of the world’s largest and unique programmes for early childhood development. The core objectives of the ICDS program are to improve the nutritional and health status of children in the age-group 0-6 years, particularly through supplementary feeding for undernourished children. Despite substantial economic growth averaging 5% per annum over the past two decades, rates of childhood under-nutrition in India have fallen only modestly during the same period. Data from India’s Demographic and Family Surveys (NFHS) indicate that in 1992, 52% of Indian children aged 0 – 3 years were moderately or severely undernourished, compared with 47% in 1998/99 and 46% in 2005/2006. In addition, the 2005/2006 NFHS found an increase in wasting among children, and higher anaemia rates among both adults and children compared with the 1998/99 survey. Despite its lofty objectives, the infrastructure for ICDS clinics is sub-optimal to facilitate achievement of its objectives. Although total budgetary allocation for the ICDS scheme increased from Rs. 529300.00 Lakh in 2007/2008 to Rs. 670500.00 Lakh in 2009/2010, this budget translates to less than 2 rupees per enrolled child and mother per day, and there is very little to show for such funding increases in the area of infrastructure. For instance, report of unannounced visits by the Karnataka State Commission for Protection of Child Rights to ICDS centres in 13 districts between July 2009 and July 2010 revealed cramped ICDS centres with no toilets for children, stale bread passed on as ‘hot meals’, drab walls without any charts as characteristic findings [33].

Discussion and Conclusion

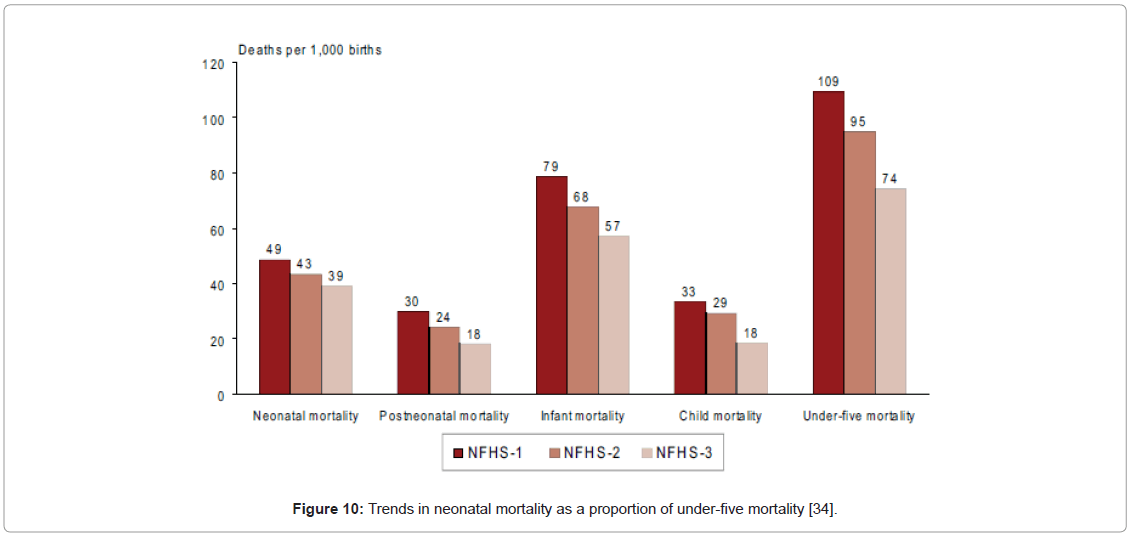

It is noteworthy that India’s under-five mortality is declining, but not at the rate expected to lead to a two-thirds reduction in 2015, compared with 1990 figures. As a result of interventions such as immunisation and improving nutrition, child mortality has declined at a faster rate than neonatal mortality, leading to a rise in the proportion of under-five deaths which occur during the neonatal period. Based on results of the three nationally representative National Family Health Surveys (NFHS), the proportion of deaths during the neonatal period in NFHS-1 and NFHS-2 were both 45%, but the proportion increased sharply to 52%, despite under-five mortality falling from 109/1000 live births in NFHS-1 to 95/1000 live births in NFHS-2 and 74/1000 live births in NFHS-3 (Figure 10) [34].

India’s progress with reducing under-five mortality is unsatisfactory, and it is very unlikely that the two-thirds reduction in under-five mortality rate in 2015 relative to 1990 baseline will be achieved. About 57% of all under-five deaths in India currently occur during the neonatal period, compared with 41% globally. Thus, initiatives to improve perinatal and neonatal care, including quality emergency obstetric care, deserve high priority. Regions and groups with high mortality levels show quite different cause-of-death patterns to the national average, leading to different intervention priorities. Low-cost mortality surveillance systems are feasible, even in poor, rural states, and among tribal populations [35]. As a first step to addressing the encumbrances to the achievement of this MDG goal, revitalization of India’s health system is important. Specifically, evidence-based strategies need to be adopted to address six core determinants of under- five mortality discussed above. In addition, initiatives to addresses social determinants of health which impact on under-five mortality, such as poverty alleviation measures, gender equality programs and improved female education need to be stepped up.

A poverty alleviation measure specifically linked to improved maternal and child health is India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) conditional cash payment scheme. Established in 2001, the JSY scheme is a conditional cash transfer to increase births in adequately resourced health centres. It is focussed on pregnant women in 10 states: Uttar Pradesh, Kashmir, Orissa, Jharkhand, Bihar, Uttaranchal, Assam, Rajasthan, Jammu, and Madhya Pradesh. These states have low rates of hospital/health centre deliveries. The JSY had a significant effect on completion of antenatal care and in-facility births. This scheme was associated with a reduction of 3.7% (95% CI: 2.2 – 5.2) perinatal deaths per 1000 pregnancies and 2.3% (95% CI: 0.97-3.7) neonatal deaths [36].

References

- Fotso J, Ezeh AC, Essendi H (2009) Maternal health in resource-poor urban settings: how does women’s autonomy influence the utilization of obstetric care services? Reprod Health 6: 9.

- Rutherford ME, Mulholland K, Hill PC (2010) How access to health care relates to under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health15: 508-519.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (2006) Joint Review of Maternal and Child Survival Strategies in China. Beijing: 50-53.

- Lawn JE, Kerber K, Enweron-Laryea CE, Cousens S (2010) 3.6 million neonatal deaths-what Is progressing and what Is not? Semin Perinatol 34: 371-386.

- Paul VK, Sachdev HS, Mavalankar D, Ramachandran P, SankarMJ, Bhandari N, et al. (2011) Reproductive health, and child health and nutrition in India: meeting the challenge. Lancet 377: 332-349.

- Das Gupta M, Rani M (2004) India’s Public Health System: How Well Does It Function at the National Level? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3447.

- World Health Organization (2000) World Health Report 2000: Health systems: improving performance. Geneva: WHO: 152-153.

- Potter C, Brough R (2004) Systemic capacity building: a hierarchy of needs. Health Policy Plan 19: 336-345.

- Berman P, Ahuja B (2008) Government health spending in India. Economic & Political Weekly, June 28.

- Govennment of Western Australia (2004) State budget 2004-5 overview. Perth, Western Australia.

- World Health Organization (2006) Mortality Country Fact Sheet, 2006 – India. Geneva, WHO, 2006.

- Morris SS, Black RE, Tomaskovic L (2003) Predicting the distribution of underfive deaths by cause in countries without adequate vital registration systems. Int J Epidemiol 32: 1041-1051.

- Bajpai N, Towle M, Vynathaya J (2011) Model districts as roadmap for public health scale up in India. Mumbai: Columbia Global Centres, South Asia.

- IndicusAnalyticus (2011) Indian Development Landscape – Health. New Delhi, India.

- Rani M, Bonu S, Harvey S (2008) Differentials in the quality of antenatal care in India. Int J Qual Health Care 20: 62-71.

- Varma GR, Kusuma YS, Babu BV (2011) Antenatal care service utilization in tribal and rural areas in a South Indian district: an evaluation through mixed methods approach. J Egypt Public Health Assoc 86: 11-15.

- World Health Organization (2009) Monitoring Emergency Obstetric Care - a handbook. Geneva: WHO,

- Yi B, Wu L, Liu H, Fang W, Hu Y, et al. (2011) Rural-urban differences of neonatal mortality in a poorly developed province of China. BMC Public Health 11: 477.

- Partnership for maternal, neonatal and child health (2011) MDG 4. Geneva: WHO.

- Bassani D, Roth DE (2011) China’s progress in neonatal mortality. Lancet 378: 1446-1447.

- Adegoke AA, Hofman JJ, Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N (2011) Monitoring and evaluation of skilled birth attendance: a proposed new framework. Midwifery 27: 350-359.

- Government of India (2009) Millennium Development Goals Country Report, 2009. New Delhi: India.

- Som S, Pal M, Chakrabarty S, Bharati P (2010) Socioeconomic impact on child immunisation in the districts of West Bengal, India. Singapore Med J 51: 406- 412.

- World Health Organization (2004) India Universal Immunisation Programme Review.

- Patel AR, Nowalk MP (2010) Expanding immunization coverage in rural India: a review of evidence for the role of community health workers. Vaccine 28: 604-613.

- Report from the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Pneumococcal Disease Prevention in the Developing World (2008) Improving global health by preventing pneumococcal disease. London: UK.

- Johnson HL, Deloria-Knoll M, Levine OS, Stoszek SK, Freimanis Hance L, et al. (2010) Systematic evaluation of serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease among children under five: the Pneumococcal Global Serotype Project. PLoS Med 7.

- World Health Organization (2011) Estimated Hib and pneumococcal deaths for children under 5 years of age. Geneva: World health Organization.

- Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, Lewis E, Ray P, et al. (2000) Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Northern California Kaiser Permanent Vaccine Study Center Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J 19: 187-195.

- Mathew JL (2008) Universal pneumococcal vaccination for India. Indian Paediatr 45: 160-161.

- World Health Organization (2009) Global Health Risks, 2009. Geneva: WHO.

- Caulfield LE, Onis M, Blössner M, Black RE (2004) Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles. Am J Clin Nutr 80: 193–198.

- Awofeso N, Rammohan A (2011) Three Decades of the Integrated Child Development Services Program in India: Progress and Problems. Health Management – different approaches and solutions, Chapter 13. Croatia: In- Tech Publishers: 243-258.

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International (2007) national family Health Survey 2005-6, Volume I, Mumbai: IIPS.

- Houweling TA, Tripathy P, Nair N, Costello A, Prost A (2010) Cause-of-death data to support MDG 4 progress. Lancet 376: 770-771.

- Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, et al. (2010) India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet 375: 2009-2023.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 18854

- [From(publication date):

January-2012 - Apr 07, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 14109

- PDF downloads : 4745