Prevalence of Needle-stick and Sharps Injuries among Healthcare Workers, Najran, Saudi Arabia

Received: 13-Jul-2012 / Accepted Date: 25-Aug-2012 / Published Date: 27-Aug-2012 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000117

Abstract

Introduction: An investigation estimates that needle-stick and sharps injuries affect about 3.5 million individuals on the global level. In healthcare workers nurses and physicians appear especially at risk.

Objectives: To examine the epidemiology of occupational sharps injuries in Health care workers.

Material and methods: It is retrospective cross-sectional study was carried out among the Health Care Workers of Maternity and Children’s Hospital, KSA from 1st January to 30th June 2012 with participation of 750 HCWs by Convenient sampling technique. Data entry and analysis was done on EPINetTM.

Results: A total of 32 cases of sharps injuries occurred during the six months period. Nurses accounted 46.9%, constituting the largest group of the Health Care Workers. Most frequently site of occurrence was operating/recovery room 34.4%. 64.5% of injuries occurred “during use of device.” In 90.6% of cases injuring item was contaminated. 59.4% injuries occurred while wearing single pair of gloves, only 21.9% with double pair of gloves. Most common site of injury was the right hand.

Conclusion: There can be serious consequences of needle stick injuries in hospitals as large proportion of injuries involves used needles and sharps if health care workers do not take appropriate measures of protection.

Keywords: Prevalence; Needle-stick injuries; Occupational exposure; Communicable diseases; Health education; Hospitals infection control; Medical waste disposal; Saudi Arabia

159202Introduction

Needle-stick and Sharp Injuries (NSIs) are accidental skin penetrating wounds caused by sharp instruments in a medical setting. They are defined as an accidental skin penetrating wound caused by hollow-bore needles such as hypodermic needles, blood-collection needles, Intra-venous (IV) catheter stylets, and needles used to connect parts of IV delivery system, scalpels and broken glass. Healthcare Workers (HCWs) face a high risk of an occupational exposure to blood, which can lead to the transmission of pathogens causing an infection and resulting in hazardous consequences for their health. Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) are of utmost concern because they can cause significant morbidity or death. The common high risk situation of such an occupational exposure is percutaneous injury which is a high risk injury.

The frequency of such events has been estimated to be about 800,000 cases in the United State of America alone (EPInet™1999 report) [1]. Another investigation estimates the rates of injuries on a global level to affect about 3.5 million individuals [2]. Among healthcare workers nurses and physicians appear especially at risk; [3] and an investigation among American surgeons indicates that almost every surgeon experienced at least one such injury during their training [4]. Causes of sharps injury include various factors like type and design of needle, recapping activity, handling/transferring specimens, collision between HCWs or sharps, during clean-up, manipulating needles in patient line related work, passing/handling devices or failure to dispose of the needle in puncture proof containers [5].

An American study shows inadvertent puncture during use, disassembly, or disposal of needles or sharp devices (called collectively, “sharps”) which creates risk beyond a simple puncture. Thus incidence of sharps injury remains unacceptably high. Policy, practice, training and new engineered devices, sharps disposal containers needed to prevent sharps injuries, and also prophylaxis after percutaneous injury [6]. Because of the environment in which HCWs work, many HCWs from physicians, surgeons, and nurses to housekeeping personnel, laboratory technicians and waste handlers are at an increased risk of accidental needle stick and sharps injuries [5]. Data from the EPINet™ system suggest that at an average hospital, workers incur approximately 30 needle-stick injuries per 100 beds per year [7]. Standard precautions are advocated for reducing the number of injuries caused by needles and sharp medical devices (“sharps injuries”), and also the effectiveness of gloves in preventing such injuries has not been established. The factors associated with gloving practices and identified associations between gloving practices and sharps-injury risk. Gloves reduced injury risk in case-crossover analyses (Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR), 0.33 {95% CI, 0.22-0.50}). In scrubbed individuals, involvement in an orthopedic procedure was associated with double gloving at injury (OR, 13.7 {95% CI, 4.55-41.3}); this gloving practice was associated with decreased injury risk (IRR, 0.20 {95% CI, 0.10-0.42}). Although the use of gloves reduces the risk of sharps injuries in health care, use among healthcare workers is inconsistent and may be influenced by risk perception and healthcare culture. Glove use should be emphasized as a key element of multimodal sharps-injury reduction programs [8]. In 2007, Association of Preoperative Registered Nurses (AORN’s) recommended Practices Task Force revised the “Recommended practices on prevention of transmissible infections in the preoperative practice setting” to recommend that health care practitioners should double-glove during invasive procedures. Previously, AORN had suggested that wearing two pairs of gloves might be indicated for some procedures. Research on the protective effects of double gloving provides compelling evidence that surgical personnel should double-glove during all surgical procedures [9]. There can be serious consequences of needle stick injuries in third world public hospitals as large proportion of injuries involves non-sterile used needles and health care workers do not take appropriate measures of protection [10]. A Mongolian study concludes that promotion of adequate working conditions, elimination of excessive injection use, and adherence to universal precautions will be important for the future control of potential infections with bloodborne pathogens due to occupational exposures to sharps [11].

The introduction of safety devices is one of the main starting points for avoidance of needle-stick injuries, and acceptance among healthcare workers is high. Further targets for preventive measures, such as training in safe working routines, are necessary for improvement of safe work conditions [12]. Engineered devices can significantly reduce the incidence of such injuries even cost analyses indicate that use of these devices will be cost-effective in the long term. But introduction of such devices should accompanied with the necessary education and training, as part of a comprehensive sharps injury prevention and control program [13]. A British study states that less number of NSIs occurs when using safety syringes and to avoid NSIs, education plays a vital role particularly with effective implementation of the change to safety syringes with appropriate training [14]. Healthcare organizations can improve staff safety by investing wisely in educational programs regarding approaches to minimize NSIs risks.

In Saudi Arabia EPINet™ Needle Stick and Sharp-Object Injury Report have been compiled using the data from 21 facilities from January 1st to March 31st, 2012. According to this report, nurses are the primary injured staff, totaling 66.4%, as compared to 7.8% of which are physicians. The primary locations where these injuries occur are in the patient room (48.9%), the Emergency Department (13.6%) and the Operating/Recovery Room (11.5%). 89.3% of the sharp items involved in the injuries are contaminated. Most of the injuries occur during injections (17.9%), drawing of venous blood samples (17.2%), and suturing (14.8%). 41.9% of the time the injuries occur during the use of the sharp items, while 18.6% are injured after use, but before disposal. The principal devices causing the injuries are disposable syringes (57.1%), 64.4% of the time they are not “safety devices”. Injuries primarily occur to the hands of the staff. 68.3% of sharps penetrated when the staff wore a single pair of gloves, 26.9% wore no gloves at all, and 4.8% wore a double pair of gloves, which may have reduced the overall penetration of the sharps [15].

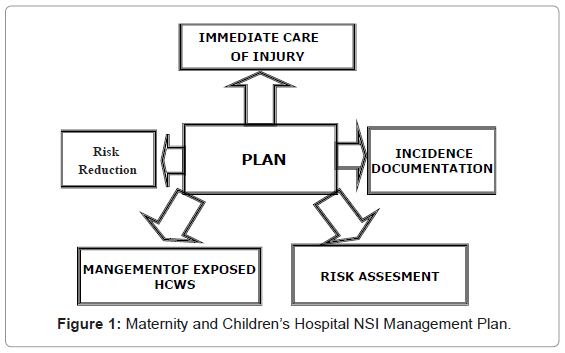

In our hospital we had a training program to reduce the number of Needle-stick injuries and to increase the awareness of our staff, through comprehensive lecture on standard precaution which includes of hand hygiene, proper disposal of sharps, proper use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), use of double gloves in operating rooms, no recapping and if inevitable use of one hand scope method and staff immunization. According to our NSIs management plan every staff should be aware about their immunization status (Figure 1).

Objectives

To examine the epidemiology of occupational sharps injuries of HCWs.

Ethical Consideration

Study was approved by ICC Ethical Board of Maternity and Children’s Hospital (MCH) Najran, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study was carried out among the HCWs (both males and females) of Maternity and Children’s Hospital, a 200 bedded hospital of Najran Saudi Arabia. The study duration was six months i.e., from 1st January to 30th June 2012 involving 750 HCWs by convenient sampling technique? The study group consisted of HCWs including doctors (consultants, specialists and residents), nurses, allied health care staff, medical waste disposal personals and cleaners.

Case definition of NSI in the present study included injuries caused by sharps such as hypodermic needles, blood collection needles, intravenous cannulas, suture needles, winged needle intravenous sets, needles used to connect parts of the intravenous delivery systems and scalpels.

The HCWs were requested to report sharps injury incidents to the Infection Control Nurse when the incidents occurred. Those who were involved in the incidents were required to personally complete an EPINet™ form which is translated in Arabic or with help of in-charge nurse especially in case of cleaners due to their low education level. Data was uploaded on EPINet™ website and finally analysis is done by EPINet™.

Written consent had been obtained from the health care workers who were involved in the study. To counter under reporting aspect of National Sheep Identification System (NSIs) Ministry of Health KSA issued a circular that any staff that becomes positive to HBV, HVC or HIV as a result of NSI his/her contract shall not be terminated.

Results

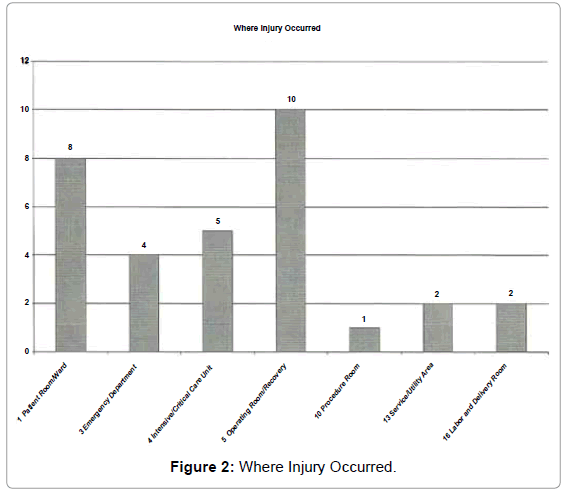

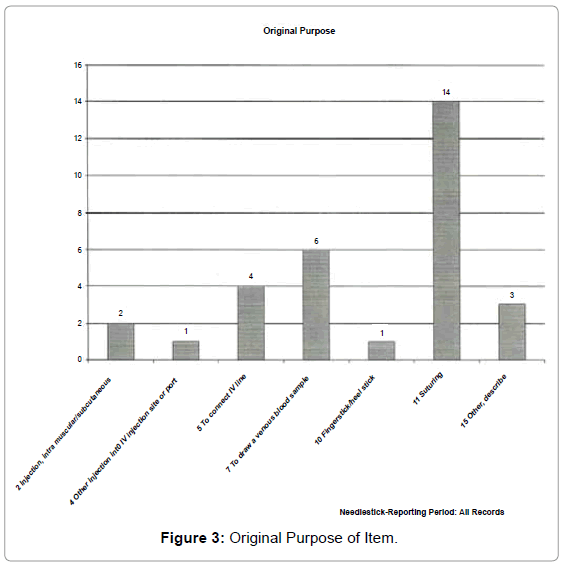

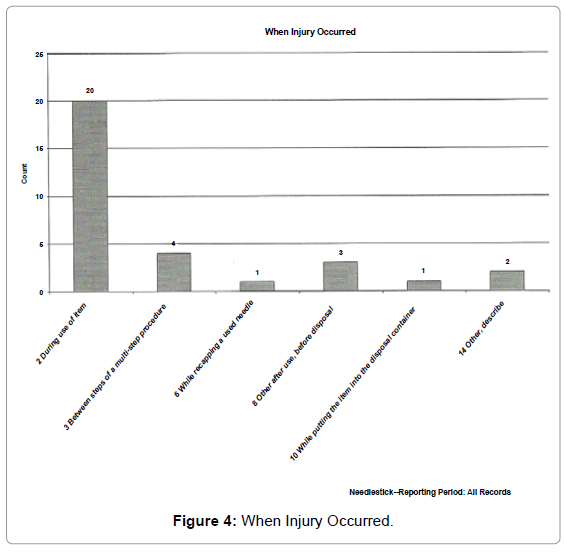

A total of 32 cases of sharps injuries occurred during the six months period. Registered nurses accounted for 15 cases 46.9%, constituting the largest group of the HCWs. The incidents occurred most frequently in the operating/recovery room which were 11 cases 34.4% (Figure 2). Twenty cases (64.5%) of the injuries occurred by needles during use of device (Figure 3 and 4) (Table 1). In twenty nine cases 90.6% injuring item was contaminated. Disposable syringe account for 11 cases 35.5% and next was suture needle which accounts for 9 cases 29%. 19 injuries (59.4%) occur while wearing single pair of gloves only 7 (21.9%) with double pair of gloves (Table 2). Most common site of NSI was right hand. Source patients were identified in 27 cases (84.4%). 96.9% of NSI causing items has no safety design (Table 3). Superficial injury with little or no bleeding occurred in 15 (46.9%) cases, moderate skin puncture with some bleeding also occurred in 15(46.9%) cases and only 2 (6.3%) cases had severe deep stick/cut with profuse bleeding.

| VARIABLES | NUMBER | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|---|

| JOB CATEGORY | ||

| Doctor (Specialist/Consultant) | 3 | 9.4% |

| Doctor (Resident) | 7 | 21.9% |

| Nurse | 15 | 46.9% |

| Surgery attendant | 4 | 12.5% |

| Technologist (Non lab) | 1 | 3.1% |

| Laundry Worker | 2 | 6.3% |

| WHERE INJURY OCCURED | ||

| Patient Room/Ward | 8 | 25.0% |

| Emergency Department | 4 | 12.5% |

| Intensive/critical Care Unit | 5 | 15.6% |

| Operating Room/Recovery | 10 | 31.3% |

| Procedure Room | 1 | 3.1% |

| Service/Utility Area | 2 | 6.3% |

| Labor and Delivery Room | 2 | 6.3% |

| WHEN INJURY OCCURED | ||

| During use of item | 20 | 64.5% |

| Between steps of a multi-step procedure | 4 | 12.9% |

| While recapping a used needle | 1 | 3.2% |

| Other after use, before disposal | 3 | 9.7% |

| While putting the item into the disposal container | 1 | 3.2% |

| Other, describe | 2 | 6.5% |

Table 1: NSIs numbers and percentages respondent categories (n=32).

| VARIABLE | NUMBER | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|---|

| WAS THE SHARP ITEM CONTAMINATED | ||

| Contaminated | 29 | 90.6% |

| Uncontaminated | 1 | 3.1% |

| Unknown | 2 | 6.3% |

| TYPE OF DEVICE CAUSING INJURY | ||

| Syringe, disposable | 11 | 35.55 |

| Syringe, blood gas | 1 | 3.2% |

| Syringe, other type | 1 | 3.2% |

| IV catheter | 3 | 9.7% |

| Needle/holder vacuum tube blood collection | 1 | 3.2% |

| Needle, unattached hypodermic | 2 | 6.5% |

| Needle, describe | 1 | 3.2% |

| Suture Needle | 9 | 29.0% |

| Scalpel, reusable | 1 | 3.2% |

| Scalpel, disposable | 1 | 3.2% |

| SHARP ITEM PENETRATED | ||

| Single pair of gloves | 19 | 59.4% |

| Double pair of gloves | 7 | 21.9% |

| No gloves | 6 | 18.8% |

Table 2: NSIs numbers and percentages respondent categories (n=32).

| VARIABLE | NUMBER | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|---|

| SOURCE PATIENT IDENTIFIABLE | ||

| Yes | 27 | 84.4% |

| No | 2 | 6.3% |

| Unknown | 3 | 9.4% |

| "SAFETY DESIGN" NEEDLE / SHARP | ||

| No | 31 | 96.9% |

| Unknown | 1 | 3.1% |

| LOCATION OF INJURY | ||

| Foot | 2 | 6.3% |

| Hand, left | 13 | 40.6% |

| Hand, right | 17 | 53.1% |

Table 3: NSIs numbers and percentages respondent categories (n=32).

Discussion

When we compared our study with other reports [16-26] there was no apparent difference in the characteristics of the NSIs. The circumstances of the injuries varied with the kinds of instruments. Due to the differences between studies, it is not possible to quantitatively synthesize their results; nonetheless, some common themes emerge, such as - needle-stick injuries are common; needle-stick injuries are often under-reported and when levels of reporting have been examined, it is common for only a small proportion to be reported; and knowledge about needle-stick injuries and possible infection from blood-borne pathogens is often low and risks under-estimated. But these facts may provide useful information for planning measures to reduce sharps injuries. In our study nurses accounted for 46.9% of cases, constituting the largest group of HCWs probably due to work load, this was also endorsed by a Swiss study mentioning NSIs were more frequent among nurses (49.2%) and doctors performing invasive procedures (36.9%) [14]. Association of Preoperative Registered Nurses (AORN’s) Recommended Practices Task Force revised the “Recommended practices on prevention of transmissible infections in the preoperative practice setting” to recommend that health care practitioners doubleglove during invasive procedures in 2007. Previously, AORN had suggested that wearing two pairs of gloves might be indicated for some procedures. Research on the protective effects of double gloving provides compelling evidence that surgical personnel should doubleglove during all surgical procedures [10] An American study showed the frequency of seeing blood on the hand after surgery was greater with single gloving than with double gloving [27]. A Pakistani study also mentions almost 90% who received NSI were not wearing gloves or taking any other protective measures at the time of injury [21]. In our study most injuries 59.4% occur while wearing single pair of gloves only 21.9% with double pair of gloves thus our study validates these studies and also the AORN’s recommendations. In our study 96.9% items causing NSIs have no safety design. An Australian study concluded introduction of self-retracting safety syringes and elimination of butterfly needles should reduce the current hollow-bore NSI by more than 70% and almost halve the total incidence of NSI [28]. A German study mentions that the rate of such injuries depends on the medical discipline. Implementation of safety devices will lead to an improvement in medical staff’s health and safety [29]. A French study also showed that passive (fully automatic) devices were associated with the lowest NSI incidence rate. Among active devices, those with a semiautomatic safety feature were significantly more effective than those with a manually activated toppling shield, which in turn were significantly more effective than those with a manually activated sliding shield [30] (P<0.001). Saudi Arabian EPINet™ report 2012 which included our hospital also showed 64.4% of the time injuring item was not safety devices but in our hospital 96.9% injuries occurred by non safety design item [7] so we can conclude that if the safety devices are provided injury rate would have been less, thus our study endorses the essentiality of safety devices.

Conclusions

Needle-stick injuries are an important and continuing cause of exposure to serious and fatal diseases among health care workers. Greater collaborative efforts by all stakeholders are needed to prevent needle-stick injuries and the tragic consequences.

Such efforts are best accomplished through a comprehensive program that addresses institutional, behavioral, and device-related factors that contribute to the occurrence of needle-stick injuries in health care workers. Critical to this effort is the elimination of needle bearing devices where safe and effective alternatives are available and the development, evaluation, and use of needle devices with safety features.

Limitations

This study has several potential limitations, primarily because it was a retrospective review of surveillance data and the number of cases was relatively small. Reporting bias may have resulted in health care workers preferentially reported exposure that they believed was more likely to result in HBV, HBC and HIV.

Acknowledgements

Our heartiest acknowledgment to Hospital Director MCH Najran KSA and Director General of Infection Control Najran Region KSA.

References

- Chalupa S, Markkanen PK, Galligan CJ, Quinn MM (2008) Needlestick and Sharps Injury Prevention: Are We Reaching Our Goals? AAACN Viewpoint.

- Prüss-Ustün A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y (2005) Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med 48: 482-490.

- Exposure prevention information network data reports. University of Virginia: International Health Care Worker Safety Center. EPINet (1999)

- Makary MA, Al-Attar A, Holzmueller CG, Sexton JB, Syin D, et al. (2007) Needle-stick injuries among surgeons in training. N Engl J Med 356: 2693-2639.

- Wilburn SQ (2004) Needle sticks and sharps injury prevention. Online J Issues Nurs 30: 5.

- Zanni GR, Wick JY (2007) Preventing needle-stick injuries. Consult Pharm 22: 400-402.

- EpinetTM (1999) Exposure prevention information network data reports. University of Virginia, International Health Care Worker Safety Center.

- Kinlin LM, Mittleman MA, Harris AD, Rubin MA, Fisman DN (2010) Use of gloves and reduction of risk of injury caused by needles or sharp medical devices in healthcare workers: results from a case-crossover study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 31: 908-917.

- Thomas-Copeland J (2009) Do surgical personnel really need to double-glove. AORN J 89: 322-328.

- Aslam M, Taj T, Ali A, Mirza W, Ali H, et al. (2010) Needle-stick injuries among health care workers of public sector tertiary care hospitals of Karachi. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 20: 150-153.

- Kakizaki M, Ikeda N, Ali M, Enkhtuya B, Tsolmon M, et al. (2011) Needle-stick and sharps injuries among health care workers at public tertiary hospitals in an urban community in Mongolia. BMC Res Notes 4: 184.

- Wicker S, Ludwig AM, Gottschalk R, Rabenau HF (2008) Needle-stick injuries among health care workers: occupational hazard or avoidable hazard? Wien Klin Wochenschr 120: 486-492.

- Tan L, Hawk JC 3rd, Sterling ML (2001) Report of the Council on Scientific Affairs: preventing needle-stick injuries in health care settings. Arch Intern Med 161: 929-936.

- Gaballah K, Warbuton D, Sihmbly K, Renton T (2012) Needle-stick injuries among dental students: risk factors and recommendations for prevention. Libyan J Med.

- Alysia Giani (2012) EPINetâ„¢ Report: Needle Stick Injury Incidents Are High. SAFE: 6

- Memish ZA, Almuneef M, Dillon J (2002) Epidemiology of needle-stick and sharps injuries in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Am J Infect Control 30: 234-241.

- Newsom DH, Kiwanuka JP (2002) Needle-stick injuries in an Ugandan teaching Hospital. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 96: 517-522.

- Shiao J, Guo L, McLaws ML (2002) Estimation of the risk of blood pathogens to health care workers after a needle stick injury in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control 30: 15-20.

- Abu-Gad HA, Al-Turki KA (2001) Some epidemiological aspects of needle stick injuries among the hospital health care workers: Eastern province. Saudi Arabia. Eur J Epidemiol 17: 401-407.

- Karstaedt AS, Pantanowitz L (2001) Occupational exposure of interns to blood in an area of high HIV seroprevalence. S Afr Med J 91: 57-61.

- Puro V, DeCarli G, Petrosillo N, Ippolito G (2001) Risk of exposure to blood borne infection for Italian Health Care Workers, by job category and work area. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 22: 206-210.

- Alzahrani AJ, Vallely PJ, Klapper PE (2000) Needlestick injuries and hepatitis B virus vaccination in health care workers. Commun Dis Public Health 2000; 3: 217-218.

- Varma M, Mehta G (2000) Needle sticks injuries among medical students. J Indian Med Assoc 98: 436-438.

- Ippolito G, Puro V, Petrosillo N, De Carli G (1999) Surveillance of occupational exposure to blood borne pathogens in health care workers: The Italian national experience. Euro Surveill 4: 33-36.

- Resnic F, Noerdlinger MA (1995) Occupational exposure among medical students and house staff at a New York City medical center. Arch Intern Med 155: 75-80.

- Kermode M, Jolley D, Langkham B, Thomas M, Crofts N (2005) Occupational exposure to blood and risk of blood borne virus infection among health care workers in rural North Indian settings. Am J Infect Control 33: 34-41.

- Korniewicz D, El-Masri M (2012) Exploring the benefits of double gloving during surgery. AORN J 95: 328-336.

- Whitby RM, McLaws ML (2002) Hollow-bore needle stick injuries in a tertiary teaching hospital: epidemiology, education and engineering. Med J Aust 177: 418-422.

- Wicker S, Jung J, Allwinn R, Gottschalk R, Rabenau HF (2008) Prevalence and prevention of needle-stick injuries among health care workers in a German university hospital. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 81: 347-354.

- Tosini W, Ciotti C, Goyer F, Lolom I, L'Hériteau F, et al. (2010) Needle-stick injury rates according to different types of safety-engineered devices: results of a French multicenter study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 31: 402-407.

Citation: Citation: Hashmi A, Al Reesh SA, Indah L (2012) Prevalence of Needle-stick and Sharps Injuries among Healthcare Workers, Najran, Saudi Arabia. Epidemiol 2:117. DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000117

Copyright: © 2012 Hashmi A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 20033

- [From(publication date): 10-2012 - Apr 03, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 14988

- PDF downloads: 5045