Research Article Open Access

Predictors of Self-Reported Adherence to Naltrexone Medication in an Outpatient Treatment for Problem Drinking

Salla Vuoristo-Myllys1,2*, Esti Laaksonen3, Jari Lahti1, Jari Lipsanen1, Hannu Alho2-4 and Hely Kalska11Institute of Behavioural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland

2National Institute for Health and Welfare, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services, Helsinki, Finland

3Department of General Practice, University of Turku, Finland

4Research Unit of Substance Abuse Medicine, University of Helsinki, Finland

- *Corresponding Author:

- Vuoristo-Myllys Salla

Institute of Behavioural Sciences

Siltavuorenpenger 1A, P.O. Box 9

00014 University of Helsinki, Finland

Tel: +358 9 1912 9483

Fax: +358 9 1912 9251

E-mail: salla.vuoristo-myllys@helsinki.fi

Received date: August 24, 2013; Accepted date: September 18, 2013; Published date: September 28, 2013

Citation: Vuoristo-Mylys S, Laaksonen E, Lahti J, Lipsanen J, Alho H, Kalska, H. et al. (2013) Predictors of Self-Reported Adherence to Naltrexone Medication in an Outpatient Treatment for Problem Drinking. J Addict Res Ther 4:159. doi:10.4172/2155-6105.1000159

Copyright: © 2013 Vuoristo-Myllys S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy

Abstract

Objective: The opioid antagonist naltrexone has been proven as an efficacious treatment for alcoholism. However, in clinical trials the reported medication adherence has often been poor, being one of the key problems associated with naltrexone treatment. There are very few studies on predictors of nonadherence, although this information would help clinicians to identify their non-compliant patients. This study investigated predictors of medication adherence in an outpatient treatment programme consisting of naltrexone and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Patients were instructed to take one tablet on each day they perceived as a risk of drinking alcohol (as-needed dosing), preferably 1 to 2 hours before anticipated time of drinking. Participants were patients (n=299) who attended a treatment programme in an outpatient clinic.

Method: Predictors of medication adherence (defined as using medication in ≥ 80% of situations of drinking) during the first five months of the treatment programme were investigated with logistic regression analyses.

Results: Average naltrexone adherence in this study was 78%. Poor adherence with naltrexone was associated with unemploymentand high craving for alcohol at treatment entry.

Conclusions: Adherence to naltrexone was generally high compared to many naltrexone studies using daily medication. Patients with high craving for alcohol may have lower adherence to naltrexone or other opioid antagonists and need practical and therapeutic strategies for improving adherence.

Keywords

Naltrexone; Adherence; opioid antagonists; Compliance

Introduction

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses [1,2] have found that opioid antagonist naltrexone is an efficacious treatment for alcohol dependence but with relatively small effect sizes. Naltrexone is believed to reduce drinking by diminishing the rewarding neurobiological effect of alcohol. In practice, naltrexone has been found to reduce patients’ craving for alcohol (defined as a strong desire to drink,[3]) [4,5] to reduce the “high” of drinking [6], and to result in less simulation and less positive reinforcing effects of alcohol use [5].

It has been suggested by Sinclair [7] that the effect of naltrexone is highly dependent on the manner in which it is used. Although most of the randomized and controlled trials on naltrexone have included daily treatment with naltrexone, an alternative approach is to use naltrexone only in situations where the patient anticipates a high risk of starting to drink alcohol. A targeted approach to the use of naltrexone has been explored in a few trials. A study by Heinälä et al. [8] showed that targeted medication-taken only when cravings occur during a 20-week period following on from a 12-week daily naltrexone treatment regimen combined with coping skills therapy was effective in maintaining the reduction in heavy drinking. Subsequent trials by Kranzler et al. [9,10] have found that targeted administration of naltrexone in addition to coping skills therapy reduces drinking more than placebo. Heinälä et al. [8] suggest that using naltrexone in a targeted manner is an effective, less expensive and perhaps safer solution for continued treatment of alcohol dependence.

Despite the fact that most of the published trials have shown the benefit of naltrexone over placebo, in some trials this advantage has not been found [11,12]. Variations in patients’ medication adherence have been proposed as an explanation for these inconsistent findings. Clinical trials that have controlled for patients’ compliance with medication regimens have shown that the effect of naltrexone is associated with medication adherence [13-15]. Similarly, a recent systematic review by Swift et al. [16] concluded that the modest effect sizes for naltrexone reported in systematic reviews and meta-analyses may at least be partly attributable to variability in naltrexone adherence rates. In trials with daily use of naltrexone reported medication adherence rates have ranged from 40% to 88% [17-19]. In studies exploring the targeted use of naltrexone, the reported adherence rates generally have been more consistent, around 86-87 % [9,10,20]. However, studies based on retrospective analyses of prescription claims databases by Kranzler et al. [21] and Hermos et al. [22] have reported that only 14-22% of patients who had an initial prescription for naltrexone persisted in picking up the prescription after 6 months.

A few factors that might affect adherence with naltrexone have been reported in the literature. Although naltrexone in generally well-tolerated, it may cause unpleasant side-effects for some patients, such as nausea and vomiting [23]. Unpleasant side-effects have been reported as one reason for non-compliance [15,24]. Other predictors of poor adherence have included lack of belief about the utility of naltrexone in managing alcohol use [24], lower urge to drink alcohol in response to alcohol stimuli in the laboratory [25] and younger age [13].

Medication non-adherence is a considerable barrier to the effective treatment of any disease, but it is of particular concern among alcoholdependent patient populations [26]. Alcohol-dependent patients who use any alcoholism medications have fewer detoxification admissions, alcoholism-related inpatient care and alcoholism-related emergency department visits in the 6 months following medication initiation in comparison to patients who have not received alcoholism medication [27]. Therefore, in addition to promoting the use of pharmacotherapy as an adjunct to psychosocial treatment in substance abuse clinics and general practices, it is important to understand the factors that may lead to non-adherence.

In natural treatment settings, medication adherence is likely to be much lower than in clinical trials in which medication use is usually monitored intensively and where the participants usually receive their study medication at no cost. In a study by Killeen et al. [28] that monitored the use of naltrexone (daily dose) in a community-based programme, the reported naltrexone adherence during the 12-week treatment was 51 %. In order to broaden this field of research, the aim of this study was to examine patients’ treatment adherence (percentage of drinking occurrences in which the patient used naltrexone) in an outpatient treatment environment for problem drinking that involved targeted use of naltrexone and cognitive behavioural therapy. As predictors of patient non-adherence, we analysed demographic information, alcohol consumption levels, drinking pattern, severity of alcohol dependence symptoms, severity of alcohol craving and comorbidity of psychiatric and/or medical disorders.

Methods

Participants

The participants were patients (n=419) who contacted a Finnish outpatient clinic between November 1998 and June 2001. Those (n=98) who decided not to enroll on the treatment programme after the first initial interview were excluded from the study. The clinic provided cognitive behavioural therapy combined with naltrexone for treating problem drinking. 10 patients were excluded from the sample for having provided incomplete data. The patients (n=12) whose liver enzyme values were more than four times the normal range were excluded, since it was not recommended that they start the medication until their liver enzyme markers had been reduced. The final study sample consisted of 299 patients. All participants gave written informed consent. Ethical permission for the study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa.

The basic treatment programme comprised the use of naltrexone and eight semi-structured cognitive-behavioural therapy sessions that were conducted according to a treatment manual based on principles of cognitive behavioural therapy. The projected length of treatment was 18-20 weeks. The aim of therapy was identification and management of high-risk situations for drinking and also reducing alcohol use to nonhazardous levels. At treatment entry, patients had an initial diagnostic interview and information about the treatment programme, including psycho-education about the neurobiological effect of naltrexone. Laboratory tests were undertaken and the patients were asked to sign a treatment contract. 50 mg naltrexone was then prescribed by a physician with the instruction to use it approximately 60 minutes before drinking in situations where the patient anticipated alcohol use. Most patients had the aim of becoming moderate drinkers rather than becoming completely abstinent.

Procedure and measures

The data on the patients’ characteristics and background information were obtained from the initial structured screening interview with a physician. A structured clinical interview was used to assess the total number (range 1-9) of DSM-IV [29] alcohol dependence symptoms for each patient. The patients were interviewed in order to obtain their medical and psychiatric history including the use of any medications. The Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS [30] ) was used to measure craving for alcohol in addition to a 10 cm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) measuring the intensity of craving and the patients were instructed to complete them during the first or second session. In addition to calculating the total score for the OCDS, the three factors ascertained by Roberts et al. [31] were calculated. The subscales are interpreted as “resistance/control impairment,” “obsession,” and “interference” and they have been found to distinguish between subjects who remained abstinent, exhibited “slip” drinking, or relapsed to heavy drinking during the 12 weeks of active treatment [31]. In VAS, patients were asked to imagine themselves in a situation where they typically drank alcohol and evaluate how strong their desire to consume alcohol was at that moment on a scale ranging from “no desire” to “if alcohol were available, I could not resist the urge to drink”. Patients’ depression was evaluated with a short version of the Beck Depression Inventory, BDI [32].

On treatment entry, a daily drinking and naltrexone use diary was introduced and the patients were taught to calculate their alcohol consumption in standard units (12 g of alcohol) for the preceding month. On the basis of that information, an average amount of weekly consumption of alcohol was calculated. First, the patients were categorised into regular drinkers (consuming alcohol weekly) and episodic heavy drinkers (those whose primary problem was occasional, not weekly heavy drinking). Second, regular drinkers were categorised using the inclusion criteria of the studies by Hemandez-Avila et al. [20] and Kranzler et al. [10] into high-risk drinkers (weekly alcohol consumption of ≥ 24 standard units for men and ≥ 18 standard units for women) and low-risk drinkers (weekly consumption of <24 standard units for men and <18 for women). Episodic heavy drinkers were not categorised according to their weekly consumption since typically they were unable to describe the amounts of alcohol consumption during their heavy drinking episodes typically lasting for several days. The patients were instructed to keep a record of their daily intake of alcohol and report their use of naltrexone in drinking diaries during the course of the treatment. Drinking diaries were monitored during every session by the clinician. If the patient had forgotten to keep the diary, it was filled retrospectively. Compliance measurement that is based on daily diaries have been shown to provide information similar to data obtained using electronic medication-use monitoring [33] and is a typical way to gather data in real-world treatment settings.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the IBS SPSS Statistics 18.0 for windows software. First, drinking diaries for the first 20 weeks of the treatment were analysed and adherence to using naltrexone before situations of drinking was calculated as a percentage of number of times a patient took naltrexone prior to drinking divided by the number of measured drinking time points in a diary. Patients were categorised into two groups: those who had good adherence (≥ 80%) to naltrexone in drinking situations and those who had poor adherence (<80%). A patient’s compliance with reporting naltrexone use in the drinking diary during the treatment was calculated as a percentage of number of weeks with full drinking diary data divided by the number of weeks the patient stayed in the treatment during the first 20 weeks of the treatment programme. The patients were then categorised into two groups: those who had high compliance (≥ 80%) in keeping a drinking diary and those who had low compliance (<80%) and the groups were compared with all other variables using χ2-tests and t-tests. The data were then examined to detect any systematic patterns in missing values and missing cases. Variables with more than 10% of missing data (education, DSM IV- and BDI-values, alcohol consumption risk group and medical/psychiatric diseases) were examined by comparing them with the medication adherence groups for missing and nonmissing cases to detect any systematic patterns. This was done using χ2-tests. Missing cases were not replaced. Patients with high and low commitment to keeping the drinking diary were compared with the medication adherence groups by using the χ2-test.

Logistic regression analyses were used to determine the unadjusted relationships between sociodemographic (age, gender, marital status, employment and education), clinical (primary drinking pattern, pretreatment alcohol consumption level and comorbid disorders) and alcohol-related or psychiatric variables (DSM IV -alcohol dependence symptoms, alcohol craving measured by the OCDS and the VAS and depression measured by the BDI) at the treatment entry and medication adherence status. The analyses were also performed adjusting all of the models for sociodemographic variables. Finally, DSM IV - alcohol dependence symptoms, the OCDS, and the BDI were examined simultaneously by including them in a multivariate analysis adjusted for sociodemographic variables. All of the above analyses were also performed with linear regression models using log-transformed continuous medication adherence as a dependent variable.

| n | % | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 294 | 45.6 (8.9) | |

| Gender | 299 | ||

| Female | 35.50% | ||

| Marital status | 286 | ||

| Not cohabiting | 25.2% | ||

| Education | 229 | ||

| high/higher intermediate | 43.7% | ||

| lower intermediate | 24% | ||

| basic or none | 32.3% | ||

| Employment | 291 | ||

| employed | 74.2% | ||

| unemployed | 14.1% | ||

| retired or other | 11.7% | ||

| Primary drinking pattern | 274 | ||

| regular drinking | 83.9% | ||

| episodic heavy drinking | 16.1% | ||

| Alcohol consumption risk group (regular drinkers) | 224 | ||

| low risk | 14.3% | ||

| high risk | 85.7% | ||

| Problematic drinking in years | 287 | 10.5 (7.6) | |

| DSM IV Alcohol dependence symptoms | 243 | 6.6 (2.0) | |

| DSM IV Alcohol dependence diagnosis | 246 | ||

| yes | 95.9% | ||

| no | 4.1% | ||

| OCDS (Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale) | 270 | 17.5 (5.7) | |

| BDI (Beck Depression Inventory) | 244 | 7.9 (5.7) | |

| Psychiatric and/or medical disorders | 248 | 5.9 (3.1) | |

| yes | 52.4% | ||

| no | 47.6% |

Note: due to missing data n varies between 224-299

M=mean; SD=standard deviation; DSM IV=The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV

Low risk=24 = standard drinks for men and = 18 standard drinks for women

High risk=24 = standard drinks for men and = 18 standard drinks for women.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of patients (n= 299) attending an outpatient treatment.

Results

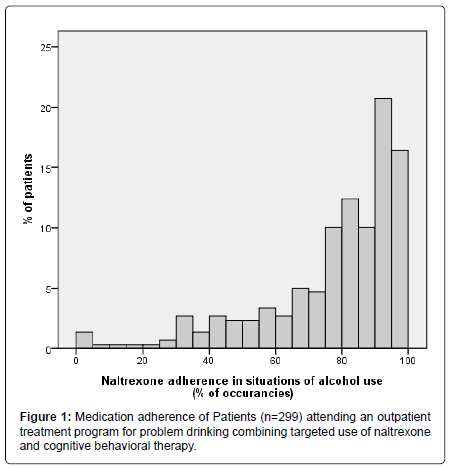

The relevant baseline characteristics of the patient sample are described in Table 1. The final study sample consisted of 299 patients, of whom a total of 159 (53%) patients completed the treatment and 140 patients dropped out (47%) prior to completion of the basic treatment programme (8 sessions). The average medication adherence in situations of alcohol use during the first four months of the treatment was 78% (SD=21). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the medication adherence among patients: 178 patients (59.5%) used naltrexone in 80% or more of the drinking situations and were categorized as having good adherence; 121 patients (40.5%) used naltrexone in less than 80% of the drinking situations and were categorized as having poor adherence. In the drinking diaries, only 8 occurences were observed when a patient used medication without drinking.

There were more missing medication adherence data in patients with comorbid disorders (χ2(1)=6.12, p<0.05). Therefore, an additional category of missing values was added to the variable for the subsequent analyses. For the other variables with more than 10% of missing data, no systematic patterns were observed in relation to medication adherence groups. The mean compliance to keeping a drinking diary during the treatment was 83% (SD=25.6, Mdn= 100) of the time spent in treatment. Those patients who were less committed to keeping a drinking diary were more likely to belong to the group of lower medication adherence (χ2(1)=31.87, p<0.001).

| Variable model | OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | continuous | 1.01 | 0.98-1.04 | 0.45 |

| Gender√?¬† (R=female) | Male | 0.99 | 0.61-1.61 | 0.98 |

| Marital status (R=living alone) | Cohabiting | 1.13 | 0.66-1.94 | 0.67 |

| Employment√?¬† (R=employed) | Unemployed | 0.43 | 0.22-0.86 | 0.02* |

| Retired | 1.28 | 0.59-2.76 | 0.53 | |

| Education (R=basic or none) | Lower intermediate | 0.89 | 0.49-1.64 | 0.72 |

| High or higher intermediate | 2.03 | 0.96-4.30 | 0.06 | |

| Primary drinking pattern (R=episodic drinker) | Regular drinker | 0.68 (0.40a) | 0.34-1.34 (0.14-1.13 a) | 0.26 (0.08a) |

| Regular drinkers’ pretreatment alcohol consumption | ||||

| level (R=low risk) | High risk | 0.58(0.53a) | 0.26-1.30 (0.20-3.02a) | 0.19 (0.20a) |

| Comorbid psychiatric and/or somatic disorders (R=no) | yes | 0.80 (1.00a) | 0.48-1.34 (0.53-1.91a) | 0.39 (0.99a) |

| missing information | 0.44 (0.56a) | 0.22-0.85 (0.25-1.24a) | 0.02* (0.15a) |

Dependent variable was categorized as 1=good adherence with naltrexone and 0=poor adherence)

R=Reference Category; A:Adjusted for Socio-demographic Variables.

Table 2: Predictors of patients√ʬ?¬? (n=299) adherence to naltrexone medication in a treatment for problem drinking: primary drinking pattern, pretreatment alcohol consumption level, comorbid disorders and socio-demographic variables.

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM IV alcohol dependence symptoms | 0.87 (0.86a) | 0.78-0.99 (0.73-1.02a) | 0.04* (0.08a) |

| Craving measured by OCDS | 0.94 (0.92a) | 0.90-0.98 (0.86-0.98a) | <0.01** (<0.01**a) |

| OCDS “resistance/control√?¬† impairment | 0.87 (0.84) | 0.81-0.94 (0.76-0.92) | <0.001*** (<0.001***) |

| OCDS “obsession” | 0.92 (0.90) | 0.85-1.00 (0.80-1.01) | 0.04* (0.06) |

| OCDS “interference” | 0.95 (1.00a) | 0.85-1.05 (0.86-1.16a) | 0.31 (0.98) |

| Craving measured by VAS | 0.86 (0.83a) | 0.79-0.94 (0.74-0.92a) | <0.001*** (<0.01**a) |

| Symptoms of depression measured by BDI | 0.96 (0.96a) | 0.92-1.01 (0.90-1.03a) | 0.08 (0.23a) |

Dependent variable was categorized as 1=good adherence with naltrexone and 0=poor adherence)

A=Adjusted for Socio-Demographic Variables Age, gender, marital status, employment and education.

Table 3: Predictors of patients' (n=299) adherence to naltrexone medication in a treatment for problem drinking:alcohol dependence symptoms, alcohol craving and symptoms of depression at treatment entry.

Table 2 and 3 present adjusted odds ratios for predictors of medication adherence. Being unemployed predicted medication adherence, p=0.02 (adjusted OR 0.43, 95% CI: 0.22-0.86). The unemployed used naltrexone in 74% (SD=3.0, Mdn=79 %,) of the drinking situations compared to 79% (SD=1.4, Mdn=85%) of those who were employed and 79 % (SD=4.3, Mdn = 90%) of those who were retired. Poor adherence was also predicted by higher symptoms of alcohol craving measured by OCDS, p<0.01, (adjusted OR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.90-0.98) and VAS p<0.001 (adjusted OR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.92-1.01) as well as higher number of alcohol dependence symptoms, p=0.04 (adjusted OR 0.87, 95% CI: 0.73-1.02). The mean OCDS score for those who belonged to the group with poor adherence was 18.8 (SD=5.4) compared to 16.8 (SD=5.7) for those who belonged to the group with good adherence. The first VAS for those with poor medication adherence was 6.7 cm (SD=2.7) compared to 5.3 cm (SD=3.25) for those who belonged to the group with good adherence. Adjusting the models for sociodemographic variables did not change the associations between the variables. In the multivariate model assessing the relative contribution of the DSM IV -alcohol dependence symptoms, the OCDS and the BDI on medication adherence, the total score of the OCDS remained statistically significant, p<.05 in the unadjusted model as well as in the model adjusted for sociodemographic variables, whereas the DSM IV -alcohol dependence symptoms and the BDI did not. In the linear regression models, all of the above results remained the same except for the association between the DSM IV-alcohol dependence symptoms (b=0.01, t(242)=1.25, p=0.21) and medication adherence and the association between the BDI and medication adherence (b=0.02, t(242)=1.18, p=0.24), which were not statistically significant or near significant.

Discussion

This study addresses an important and relevant topic in the field of alcohol dependence treatment, namely adherence to medication in the treatment of alcohol dependence, and extends the previous literature concerning naltrexone adherence. Despite the fact that there is strong evidence about the efficacy of using pharmacotherapy in conjunction with psychosocial treatments, medication adherence is low in the alcohol-dependent population [26]. The mean naltrexone adherence rate of 78% observed for the first four months of this treatment is generally very good considering the fact that this study was conducted in a real-world treatment setting. The adherence rate was better than in the study by Killeen et al. [28] who reported an adherence rate of 51%. in a 12-week community treatment programme in which the patients were randomised to receive either 50 mg of naltrexone daily or placebo. In clinical trials of targeted naltrexone the adherence rates have been higher, 86-87 % (10,20), but the treatment length in these trials has been only 8-12 weeks, the subjects have received the medication at no cost and their study medication use has been monitored using more sophisticated, electronic daily medication monitoring methods. In this study, the patients were encouraged to report their naltrexone use in drinking diaries during the treatment and the diaries were returned to the clinician during each therapy session. This is likely to be a more typical way to monitor medication use in standard clinical settings. Moreover, in light of the results by Kranzler et al. [21] and Hermos et al. [22] who reported that only 14-22% of the patients who filled an initial prescription for naltrexone persisted in obtaining the medication for 6 months, these results indicate that patients in our study were very committed to using naltrexone in situations of drinking. However, as we have reported before [34], medication adherence was not related to better treatment outcome in this real-world study, because the patients who were drinking less before and during the treatment, had significantly better adherence than those who were drinking more before and during the course of the treatment.

Possible reasons for the high medication adherence in our study may be that the treatment programme included psycho-education about the neurobiological effects of naltrexone and that the clinic and its staff were all specialised in this treatment model (naltrexone and CBT). Educational approaches have been found to be most effective when combined with behavioural techniques and supportive services [35] and, as Pettinati [26] points out, a clinician’s attitude about the effectiveness of a medication is critical because it may be transferred to the patient. One reason for a good medication adherence rate may be related to using naltrexone in a targeted manner instead of as a daily dose, since prescribed dosage has been proven to be inversely related to compliance [36]. In particular, those patients who are not drinking on a daily basis may find it hard to motivate themselves to use daily medication.

One predictor of medication adherence that emerged in this study was unemployment. Poor adherence has been associated with the cost of the medication [37] and lack of social support [38], which may be more common in patients who are unemployed. Poor adherence was also predicted by intense symptoms of alcohol craving at treatment entry, specifically low control over alcohol use. This finding was somewhat contrary to the finding by Rohsenow et al. [25] who found that naltrexone compliance was greater among those with a higher urge to drink in response to alcohol stimuli in the laboratory. This inconsistency may be explained by the fact that the cue expose used in the Rohsenow et al. study may have worked in itself as an intervention, motivating patients with higher craving for alcohol for using medication. Monti et al. [39] have formulated some factors that may increase motivation to drink: cognitions (such as expectancies about the reinforcing effects of alcohol), negative affect (such as boredom and depression) and physiological states (such as neuronal changes in the mesolimbic dopamine circuitry of the brain). These motivations, particularly a reluctance to give up the pleasure associated with drinking alcohol, may be more pronounced in patients with high craving for alcohol and may lead a patient to choose not to use the medication. However, it should also be noted that different subtypes of patients could have different mechanisms at the basis of their symptoms of craving [40]. Finally, there is evidence that patients with substance dependence have more problems in the executive processes of working memory [41], which may have led some patients with more severe alcohol-related problems simply to forget to take the pill.

One limitation of this study is that it did not take account of intreatment, extraneous, or intrinsic factors that may have influenced the medication adherence. The patients in this study were also generally highly motivated and not resistant to treatment, since most of them were aware of the content of the programme prior to entering the treatment, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Finally, the lack of more sophisticated measures to monitor medication adherence, such as electronic monitoring or the used of bioverification, limits the internal validity of the study. Notwithstanding these limitations, the main strength of this study is that it has high external validity. These results may be generalised to substance abuse clinics and general practices treating patients with alcohol dependence with targeted use of naltrexone, namely these results may help evaluate patients’ adherence to naltrexone in real-life settings.

Considering the fact that the effect of naltrexone is associated with medication adherence [13-15], it is important to monitor patients’ medication use during treatment. If non-adherence with medication is identified as a problem in treatment, “the clinician should address the issue with the patient in order to uncover the rationale behind it in an empathetical and non-judgemental way”, as Pettinati [26] suggests. Patients with non-adherence to naltrexone should be offered alternative medications to reduce their alcohol consumption, such as disulfiram or acamprosate or helped with behavioural interventions and reinforcements enhancing adherence. Osterberg and Blaschke [42] remind us of the possibilities that come with new technology, such as cell phones, personal digital assistants and pillboxes with paging systems, in helping patients to meet the goals of a medication regimen.

In conclusion, these results are of clinical importance when treating patients with alcohol dependence with naltrexone. Patients who have high craving for alcohol need practical and therapeutic strategies to enhance medication adherence in real-life alcohol treatment settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank CEO Jukka Keski-Pukkila, from ContrAl Clinics, Finland for his permission to use the data for the current study and Risto Heikkinen, MA (Stat) for his guidance with the statistical analyses. The appreciation is extended to Panu Keski-Pukkila who helped with gathering the data and to Benita Jakobson and David Sinclair for their help in planning the study.

References

- Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S, Vecchi S, Srisurapanont M, et al. (2010) Opioid Antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 9: CD004332.

- Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N (2005) Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 8: 267-280.

- World Health Organization. (2004) Global status report on alcohol.

- Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham PRN, Waid, LR, Myrick, H, et al. (2005) Naltrexone combined with either cognitive behavioral or motivational enhancement therapy for alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol 25: 349-357.

- Davidson D, Palfai T, Bird C, Swift R (1999) Effects of naltrexone on alcohol self-administration in heavy drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23: 195-203.

- Volpicelli JR, Watson NT, King AC, Sherman CE, O'Brien CP (1995) Effect of naltrexone on alcohol "high" in alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry 152: 613-615.

- Sinclair JD (2001) Evidence about the use of naltrexone and for different ways of using it in the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol Alcohol 36: 2-10.

- Heinälä P, Alho H, Kiianmaa K, Lönnqvist J, Kuoppasalmi K, et al. (2001) Targeted use of naltrexone without prior detoxification in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a factorial double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 21: 287-292.

- Kranzler HR, Armeli S, Tennen H, Blomqvist O, Oncken C, et al. (2003) Targeted naltrexone for early problem drinkers. J Clin Psychopharmacol 23: 294-304.

- Kranzler HR, Tennen H, Armeli S, Chan G, Covault J, et al. (2009) Targeted naltrexone for problem drinkers. J Clin Psychopharmacol 29: 350-357.

- Kranzler HR, Modesto-Lowe V, Van Kirk J (2000) Naltrexone vs. nefazodone for treatment of alcohol dependence. A placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 22: 493-503.

- Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, Kirk GF, Rosenheck RA; Veterans Affairs Naltrexone Cooperative Study 425 Group (2001) Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med 345: 1734-1739.

- Baros AM, Latham PK, Moak DH, Voronin K, Anton RF (2007) What role does measuring medication compliance play in evaluating the efficacy of naltrexone? Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31: 596-603.

- Chick J, Anton R, Checinski K, Croop R, Drummond DC, et al. (2000) A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence or abuse. Alcohol Alcohol 35: 587-593.

- Volpicelli JR, Rhines KC, Rhines JS, Volpicelli LA, Alterman AI, et al. (1997) Naltrexone and alcohol dependence. Role of subject compliance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54: 737-742.

- Swift R, Oslin DW, Alexander M, Forman R (2011) Adherence monitoring in naltrexone pharmacotherapy trials: a systematic review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 72: 1012-1018.

- Bouza C, Angeles M, Muñoz A, Amate JM (2004) Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 99: 811-828.

- Croop RS, Faulkner EB, Labriola DF (1997) The safety profile of naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism. Results from a multicenter usage study. The Naltrexone Usage Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54: 1130-1135.

- Namkoong K, Farren CK, O'Connor PG, O'Malley SS (1999) Measurement of compliance with naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: research and clinical implications. J Clin Psychiatry 60: 449-453.

- Hernandez-Avila CA, Song C, Kuo L, Tennen H, Armeli S, et al. (2006) Targeted versus daily naltrexone: secondary analysis of effects on average daily drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30: 860-865.

- Kranzler HR, Stephenson JJ, Montejano L, Wang S, Gastfriend DR (2008) Persistence with oral naltrexone for alcohol treatment: implications for health-care utilization. Addiction 103: 1801-1808.

- Hermos JA, Young MM, Gagnon DR, Fiore LD (2004) Patterns of dispensed disulfiram and naltrexone for alcoholism treatment in a veteran patient population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28: 1229-1235.

- Streeton C, Whelan G (2001) Naltrexone, a relapse prevention maintenance treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Alcohol Alcohol 36: 544-552.

- Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP, Rabinowitz AR, Wortman SP, Oslin DW, et al. (2006) The status of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: specific effects on heavy drinking. J Clin Psychopharmacol 26: 610-625.

- Rohsenow DJ, Colby SM, Monti PM, Swift RM, Martin RA, et al. (2000) Predictors of compliance with naltrexone among alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24: 1542-1549.

- Pettinati HM (2006a) Improving medication adherence in alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychiatry 67: 23-29.

- Mark TL, Montejano LB, Kranzler HR, Chalk M, Gastfriend DR (2010) Comparison of healthcare utilization among patients treated with alcoholism medications. Am J Manag Care 16: 879-888.

- Killeen TK, Brady KT, Gold PB, Simpson KN, Faldowski RA, et al. (2004) Effectiveness of naltrexone in a community treatment program. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28: 1710-1717.

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (4thedn), Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press.

- Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham PK (1996) The obsessive compulsive drinking scale: A new method of assessing outcome in alcoholism treatment studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53: 225-231.

- Roberts JS, Anton RF, Latham PK, Moak DH (1999) Factor structure and predictive validity of the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23: 1484-1491.

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G (1997) Cognitive therapy for depression: A treatment manual. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Feinn R, Tennen H, Cramer J, Kranzler HR (2003) Measurement and prediction of medication compliance in problem drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27: 1286-1292.

- Vuoristo-Myllys S, Lipsanen J, Lahti J, Kalska H, Alho H (2013) Predictors of outcome in an outpatient treatment for problem drinkers including cognitive behavioral therapy and opioid antagonist naltrexone. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse

- Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, Mechanic D (2002) Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 159: 1653-1664.

- Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C (2001) A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther 23: 1296-1310.

- Balkrishnan R (1998) Predictors of medication adherence in the elderly. Clin Ther 20: 764-771.

- DiMatteo MR (2004) Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 23: 207-218.

- Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Hutchison KE (2000) Toward bridging the gap between biological, psychobiological and psychosocial models of alcohol craving. Addiction 95 Suppl 2: S229-236.

- Addolorato G, Leggio L, Abenavoli L, Gasbarrini G; Alcoholism Treatment Study Group (2005) Neurobiochemical and clinical aspects of craving in alcohol addiction: a review. Addict Behav 30: 1209-1224.

- Bechara A, Martin EM (2004) Impaired decision making related to working memory deficits in individuals with substance addictions. Neuropsychology 18: 152-162.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 353: 487-497.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction Recovery

- Alcohol Addiction Treatment

- Alcohol Rehabilitation

- Amphetamine Addiction

- Amphetamine-Related Disorders

- Cocaine Addiction

- Cocaine-Related Disorders

- Computer Addiction Research

- Drug Addiction Treatment

- Drug Rehabilitation

- Facts About Alcoholism

- Food Addiction Research

- Heroin Addiction Treatment

- Holistic Addiction Treatment

- Hospital-Addiction Syndrome

- Morphine Addiction

- Munchausen Syndrome

- Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

- Nutritional Suitability

- Opioid-Related Disorders

- Relapse prevention

- Substance-Related Disorders

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16270

- [From(publication date):

September-2013 - Apr 06, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11631

- PDF downloads : 4639