Predictors of Intention to Quit Cigarette Smoking among Jordanian Adults

Received: 31-Aug-2011 / Accepted Date: 20-Oct-2011 / Published Date: 25-Oct-2011 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000103

Abstract

Objective: Having an intention to quit smoking is associated with quitting and is a step toward the required behavioral change. This study examines the predictors of an intention to quit and predictors of previous quitting attempt in a sample of adult Jordanian smokers (n=260).

Methods: A cross-sectional study in a convenient sample of willing adults in Amman, Jordan (n=600). The survey included socio-demographic characteristics, history of tobacco smoking, environmental and behavioral determinants of smoking like peer influence, and perceived harm. Individuals who smoked a cigarette during the previous month were considered smokers and included in further analysis (n=260). Three multivariate logistic regression models were constructed to determine predictors of intention to quit in the next year, next 30-days, and predictors of a previous quitting attempt.

Results: We found a high level of interest in quitting with the majority of the sample having had a previous quitting attempt (60%), more than half of the population considering quitting in the next year (57%), and 42% considering quitting in the next 30 days. Predictors found to be significant in this study, include heaviness of smoking, media antismoking message exposure, medical education, previous quit attempts, and smoker’s mental health.

Conclusion: Findings document a high level of interest in quitting underscoring the urgent need to develop interventions that foster this desire and ensure success. Predictors found to be significant in this study should be considered in designing an effective intervention in this Middle Eastern country.

Keywords: Smoking; Cigarette; Intention; Quitting; Jordan

158420Introduction

Tobacco use causes approximately 443,000 premature deaths annually in the United States (US) [1] and 5.4 million worldwide [2] with annual economic losses to the US society estimated at $193 billion with $96 billion in direct medical costs [1]. It remains the leading preventable cause of premature death worldwide [2,3], and is expected to remain as such in both developed and developing countries in 2020 [4].

Tobacco use in the Middle East is reported to be the highest worldwide [5] with smoking rates usually ranging from 40-60% for cigarettes and reaching rates of 77% for men and 35% in women, in some Arab countries. These rates continue to rise [6]. Consequently, smoking habits have been cited as one of the major reasons for a 181% expected increase in cancer mortality by the year 2020, compared to a 26% increase in developed countries [7].

Jordan is a small Middle Eastern country with a population of 5,800,000 where smoking is relatively common [8]. A survey by the ministry of health found a 27-29% smoking rate in the Jordanian population with an increase between 2007-2009, and 13% cigarette smoking rate among youth aged 13-15 [8], while some reports show 48% of men and 10% of women to be cigarette smokers [9]. Studies among university students in Jordan documented smoking rates ranging from 16% to 33% [6,10,11]. These numbers underscore the importance of developing effective interventions specifically tailored to this population that can help smokers quit as tobacco related diseases including heart disease, stroke, cancers and respiratory diseases, can be reduced by quitting smoking especially with absence of illness at the time of quitting [12].

According to Theory of Reasoned Action/planned behavior (TRA), behavior is influenced by the intention to perform the behavior which is influenced by the subjective norms, attitudes, as well as self efficacy or confidence of the ability to successfully perform the behavior [13]. Changes in addictive behavior involve progression through several stages as described by stage-based models of behavior change [14]. Starting at no desire to quit, progression is made towards forming an intention to stop. The intention is followed by preparing for the behavior change, then implementing the behavior change and finally maintaining it [14,15]. An intention to quit is an important preliminary step for the behavioral change [15-17]. Even though having an intention to quit is not the sole predictor of a smoking cessation, intention is highly associated with attempting to quit [15,18,19] and with smoking cessation [15,18-20]. To date, information regarding quitting intentions among the adult Jordanian population is lacking. Our objectives are to examine the predictors of intention to quit among a convenience sample of adult smokers in Jordan and predictors of a previous quitting attempt. This knowledge is critical in identifying subpopulations more likely to quit and in developing effective interventions beneficial in helping smokers break the habit.

Methods

Participants and study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted in a convenience sample of willing adults, 18 years or older, in Amman, Jordan from July, 2009 through July, 2010.

Survey procedures and measures

The survey was approved by the institutional review board and adapted from a previously used self-report survey [21,22].

Survey distribution sites included a physician clinic, 2 academic institutions, 3 shopping centers, and a marketing company. These sites were used to include adult participants of different ages, socioeconomic statuses, and professions. Adults entering the sites were asked if they were willing to participate in an anonymous survey regarding smoking habits and attitudes that would require 15-20 minutes to complete. If they agreed, they were given a survey and asked to place it in a sealed drop box available at each of these sites when finished.

Survey questions covered socio-demographic characteristic, diagnoses of diseases linked to smoking, symptoms affected by smoking like shortness of breath, mental health, past use of different tobacco forms and other addictive substances like alcohol, perceived harm, family and friends’ tobacco use, previous quitting attempts and feelings when trying to quit, as well as addiction level questions for nicotine dependence [23]. Participants who smoked one or more cigarettes during the past 30 days where considered current smokers. This definition has been used in previous studies [24-26] and was based on a survey question (How many cigarettes did you smoke in the last 30 days?).

Two outcome variables were identified: Intention to quit in the next month vs. not, based on the question: (Are you seriously thinking of quitting smoking in the next month?) and intention to quit in the next year vs. not, based on the question: (Are you seriously thinking of quitting smoking in the next year?). These 2 variables were identified to determine if there are any differences of the predictors between an immediate intention to quit and a longer term intention. In addition, an outcome variable of having a previous quitting attempt vs. not was constructed as previous quit attempts have been associated subsequent quit attempts [18,27] and successful quitting may require multiple attempts [15]. This was based on the question (Have you ever tried to quit cigarette smoking?).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and chi-square analyses were used to determine the frequencies and associations of sample characteristics with the outcomes previously defined. Univariate analyses of participant characteristics were carried out with the three outcome variables, and results were presented as unadjusted Odds Ratios (OR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). Three multivariate logistic regression models were carried out to determine predictors of intention to quit with two outcomes, and predictors of quitting attempts after assessing co-linearity between the independent variables. Variable with a probability of 0.2 or less (p<0.2) in the univariate analyses were included and backward elimination was used to arrive at the final models. Gender and age were kept in all multivariate models. Results were presented as adjusted ORs with 95% CIs. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS statistical package version 9.2.

Results

Sample characteristics

The response rate was approximately 60% with 600 respondents completing the survey. As the survey required 15-20 minutes to complete, the main reason for nonparticipation was lack of time. Current smokers, defined as smoking within the last 30 days, comprised 43.3% of the sample (n=260) and were included in further analysis. Of those, the majority of participants were male (76.3%) and 55% were older than 25 years old. Mean age ± SD was approximately 28.7 ± 7.9 years old. Approximately 42% of the smokers were considering quitting within the next month, and 57% in the next year. Previous quitting attempts were carried out by 60% of the sample. Table 1 summarizes the results of participant characteristics and chi-square analysis with the three outcome variables.

| Thinking to quit in the next year (56.76%) |

Thinking to quit in the next 30 days (42.45%) |

Had quit cigarette smoking before (60.35%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N (%) | % | p-value | % | p-value | % | p-value |

| Demographics and health condition | |||||||

| Gender Female Male |

60(23.72%) 193(76.28%) |

63.41% 56.57% |

0.4244 | 42.50% 42.77% |

0.9752 | 55.81% 62.57% |

0.4142 |

| Age, (years) ≦25 >25 |

117(45.00%) 143(55.00%) |

56.18% 57.14% |

0.8871 | 42.53% 42.40% |

0.9851 | 63.54% 58.02% |

0.4004 |

| Occupation/major Medical field Non medical field |

63 (28.64 %) 157(71.36%) |

68.42% 53.38% |

0.0544 | 53.70% 35.11% |

0.0192* | 74.55% 53.24% |

0.0065* |

| Dyspepsia Sometimes or frequently Rarely |

78 (30.35 %) 179 (69.65 %) |

70.77 % 50.97 % |

0.0068* | 53.33 % 37.75 % |

0.0386* | 69.84% 56.52% |

0.0670 |

| What they felt during last week | |||||||

| Bothered by something Not at all Yes |

88 (35.20 %) 162 (64.80 %) |

46.25 % 63.70 % |

0.0124* | 42.11 % 42.31 % |

0.9774 | 49.37% 66.19% |

0.0148* |

| Felt like something good was going to happen Not at all Yes |

95 (39.42 %) 146 (60.58 %) |

48.75 % 62.02 % |

0.0598 | 36.84% 45.53 % |

0.2280 | 51.25% 67.42% |

0.0191* |

| Felt down and unhappy Not at all Yes |

72 (28.69 %) 179 (71.31 %) |

41.79 % 64.19 % |

0.0021 * | 36.51 % 45.45 % |

0.2317 | 46.97% 66.23% |

0.0074* |

| Felt lonely, like having no friends Not at all Yes |

155 (60.31 %) 102 (39.69 %) |

50.72 % 67.07 % |

0.0179* | 34.11 % 55.56 % |

0.0022* | 53.57% 71.76% |

0.0068* |

| Felt tired Not at all Yes |

49(19.29%) 205(80.71%) |

40.43% 61.05% |

0.0115* | 26.67% 46.95% |

0.0148* | 43.48% 64.61% |

0.0090* |

| Medias message about smoking | |||||||

| TV/radio/movies/internet….. Saw messages against smoking Haven’t seen an against one |

203 (78.08 %) 57 (21.92 %) |

62.21 % 38.00 % |

0.0024* | 45.83 % 29.55 % |

0.0517 | 61.02% 58.00% |

0.7002 |

| Tobacco and substances use experience | |||||||

| Cigarettes quitting experiences Never quit before Quit before |

90 (39.65 %) 137 (60.35 %) |

30.95 % 72.87 % |

<0.0001* | 20.25 % 53.23 % |

<0.0001* | N/A | |

| Tried quitting for at least 24 hours in the past month Tried before Never |

106 (46.49 %) 122 (53.51 %) |

74.75 % 41.88 % |

<0.0001* | 55.91 % 32.74 % |

0.0008* | N/A | |

| Cut down the number of cigarettes in the past month Cut down/try to cut down Did not try to cut down |

162 (69.23 %) 72 (30.77 %) |

63.23 % 40.91 % |

0.0022* | 49.01 % 26.67 % |

0.0031* | N/A | |

| Addiction level | |||||||

| Cigarette consumption Heavy smoker (>10/day) Light smoker (≦10/day) |

139 (53.46 %) 121 (46.54 %) |

49.22 % 67.02 % |

0.0082* | 33.06 % 55.68 % |

0.0010* | 56.25% 65.66% |

0.1508 |

| Is it hard to keep from smoking where you are not allowed to? Yes No |

114 (51.12 %) 109 (48.88 %) |

48.60 % 65.69 % |

0.0126* | 32.35 % 54.64 % |

0.0015* | 51.35% 71.00% |

0.0035* |

| How soon do you smoke 1st cigarette after wake up? Before noon In the afternoon/evening |

170(77.27%) 50(22.73%) |

57.41% 63.04% |

0.4933 | 38.61% 57.14% |

0.0308* | 62.11% 60.42% |

0.8321 |

| Which cigarette would you most hate to give up? First cigarette in the morning Any other cigarette after that |

111(51.87%) 103(48.13%) |

57.41% 62.37% |

0.4749 | 39.81% 46.74% |

0.3290 | 59.62% 64.29% |

0.4946 |

| Still smoke even seriously sick? Yes No |

58(25.55%) 169(74.45%) |

50.94% 57.23% |

0.4248 | 29.17% 45.45% |

0.0456* | 55.56% 62.50% |

0.3662 |

| Smoke more during the first 2 hours of the day than the rest? Yes No |

59(27.44%) 156(72.56%) |

67.86% 53.06% |

0.0569 | 47.27% 39.57% |

0.3267 | 63.16% 59.46% |

0.6275 |

*total numbers do not add up to 260 because of missing value

Table 1: Characteristics of participants of a sample of adult cigarette smokers in Jordan.

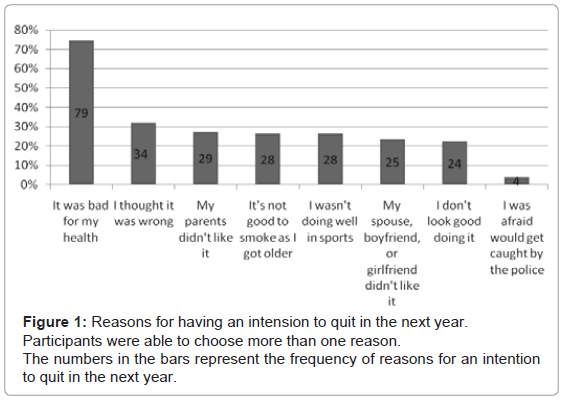

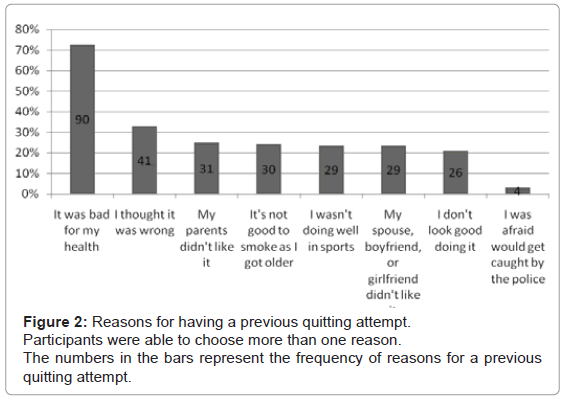

Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the different reasons cited for wanting to quit and for a previous quitting attempt, respectively. The most common reason, cited by more than two thirds of the population, was the belief that smoking was bad for one’s health.

Logistic regression analyses: predictors and correlates of cigarette smoking

Table 2 summarizes the results of univariate logistic regression and multivariate logistic regression with the intention to quit among two outcome variables (unadjusted rates and adjusted rates) outcomes.

| Thinking to quit in the next year | Thinking to quit in the next 30 days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

| Demographics and health condition | ||||

| Gender Female Male |

Reference 0.75 (0.37 –1.52) |

Reference 1.35 (0.52 –3.56) |

Reference 1.01 (0.50 –2.03) |

Reference 2.11 (0.87 –5.12) |

| Age, (years) ≦25 >25 |

Reference 1.04 (0.61 –1.79) |

Reference 1.37 (0.70 –2.66) |

Reference 1.00 (0.57 –1.73) |

Reference 1.46 (0.76 –2.79) |

| Dyspepsia Sometimes or frequently Rarely |

Reference 0.43(0.23 –0.80)* |

Reference 0.53 (0.29–0.97) |

||

| What they felt during last week | ||||

| Bothered by something Not at all Yes |

Reference 2.04 (1.16–3.58)* |

Reference 1.01 (0.57 –1.79) |

||

| Felt like something good was going to happen Not at all Yes |

Reference 1.72 (0.98 –3.02) |

Reference 1.43 (0.80 –2.57) |

||

| Felt down and unhappy Not at all Yes |

Reference 2.50 (1.38–4.51)* |

Reference 2.74 (1.35–5.56)* |

Reference 1.45 (0.79 –2.67) |

|

| Felt lonely, like having no friends Not at all Yes |

Reference 1.98 (1.12 –3.50)* |

Reference 2.42 (1.37 –4.27)* |

Reference 2.37 (1.22 –4.62)* |

|

| Medias message about smoking | ||||

| TV/radio/movies/internet….. Saw messages against smoking Haven’t seen an against one |

Reference 0.37 (0.20–0.71)* |

Reference 0.29 (0.13–0.64)* |

Reference 0.50 (0.24 –1.01) |

|

| Tobacco and substances use experience | ||||

| Cigarettes quitting experiences Never quit before Quit before |

Reference 5.99(3.28 –10.96)* |

Reference 5.67 (2.92–11.03)* |

Reference 4.48 (2.33 –8.60)* |

Reference 3.29 (1.65 –6.55)* |

| Tried quitting for at least 24 hours in the past month Tried before Never |

Reference 0.24 (0.14-0.44)* |

Reference 0.38 (0.22 -0.68)* |

||

| Cut down the number of cigarettes in the past month Cut down/try to cut down Did not try to cut down |

Reference 0.40 (0.22-0.73)* |

Reference 0.38 (0.20 –0.73)* |

||

| Addicted level | ||||

| Cigarette consumption Heavy smoker (>10/day) Light smoker (≦10/day) |

Reference 2.10 (1.21 –3.64)* |

Reference 2.43 (1.13–5.19)* |

Reference 2.54 (1.45 –4.47)* |

Reference 4.05 (1.92 –8.55)* |

| Is it hard to keep from smoking where you are not allowed to? Yes No |

Reference 2.03 (1.16-3.54)* |

Reference 2.52 (1.42 –4.48)* |

||

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval

*p≤0.05

Table 2: Univariate and multivariate logistic regression results of intention to quit at one year and one month among adult cigarette smokers in Jordan.

In the adjusted models, participants who had a previous quitting attempt were more likely to want to quit in both of the models: One year model (OR=5.67, 95% CI=2.92-11.03); and 30-day model (OR=3.29, 95% CI=1.65-6.55). Those who smoked less than 10 cigarettes per day were more likely to want to quit in both of the models compared to those who smoked 10 cigarettes or more per day: One year model (OR=2.43, 95% CI=1.13- 5.19); and 30-day model, (OR=4.05, 95% CI=1.92-8.55). Participants who had not seen an advertisement against smoking were less likely to want to quit in the next year compared to those who have seen a message against smoking (OR=0.29, 95% CI=0.13-0.64). Participants who felt lonely were more likely to have a desire to quit in the next 30 days (OR=2.37, 95% CI=1.22-4.62), and participants who felt down and unhappy were also more likely to have an intention to want to quit in the next year (OR =2.74, 95% CI=1.35- 5.56). A number of variables were significant in the unadjusted models, but were no longer associated after adjusting for confounders in the multivariate models. These included suffering from dyspepsia, some variables describing feelings in past week, and having difficulty smoking in areas where it is not allowed.

Table 3 shows the results of the unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analysis with the final outcome of having a previous quitting attempt or not. Participants in the nonmedical field were less likely to have had a quitting attempt compared to those in medical fields (OR=0.37, 95% CI= 0.17-0.81). Participants who felt bothered in the past week (OR=2.26, 95% CI=1.11-4.60) or felt unhappy (OR=2.60, 95% CI=1.27-5.36) were more likely to have a previous quitting attempt than those who did not. Although those who found it difficult to refrain from smoking in areas where smoking was not allowed were less likely to quit in the unadjusted model, this was not significant in the adjusted model.

| Had tried quitting cigarette smoking before | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

||

| Demographics and health condition | |||

| Gender Female Male |

Reference 1.32 (0.68- 2.60) |

Reference 1.54 (0.69- 3.44) |

|

| Age, (years) ≦25 >25 |

Reference 0.79 (0.46- 1.36) |

Reference 1.13 (0.57- 2.24) |

|

| Occupation/major Medical field Non medical field |

Reference 0.39 (0.20 –0.78)* |

Reference 0.37 (0.17–0.81)* |

|

| What they felt during last week | |||

| Bothered by something Not at all Yes |

Reference 2.01 (1.14–3.53)* |

Reference 2.26 (1.11–4.60)* |

|

| Felt like something good was going to happen | |||

| Not at all Yes |

Reference 1.97 (1.11 –3.48)* |

||

| Felt down and unhappy Not at all Yes |

Reference 2.22 (1.23–3.99)* |

Reference 2.60 (1.27–5.36)* |

|

| Felt lonely, like having no friends | |||

| Not at all Yes |

Reference 2.20 (1.24 –3.92)* |

||

| Felt tired Not at all Yes |

Reference 2.37 (1.23–4.59)* |

||

| Addicted level | |||

| Is it hard to keep from smoking where you are not allowed to? | |||

| Yes No |

Reference 2.32 (1.31 –4.10)* |

||

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval

* p≤0.05

Table 3: Univariate and multivariate logistic regression of a quitting attempt among adult cigarette smokers in Jordan.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine intention to quit and having a quitting attempt among a sample of adults in Jordan. We found that the majority of the sample smokers have attempted to quit before (60%), more than half of the population was considering quitting in the next year (57%), and 42% were considering quitting in the next month. As there are many challenges to quitting, there is a great need to develop interventions that can foster this desire and ensure success. A previous study in Jordan among 393 healthcare workers who are smokers reported that 53% expressed a desire to quit and 60.6% had a quitting attempt [28]. These rates are consistent with our study. Two survey-based studies in Syria, a neighboring country in the Middle East, showed slightly higher rates for interest in quitting, 74% [29] and 75% [26], for cigarette smokers. Previous quitting attempts was reported in 58% of the sample in one of the studies [29], consistent with this study’s finding, but slightly higher in the other (78%).

Participants cited many reasons for wanting to quit or for a previous quit attempt. The most common, cited by more than two thirds of the population, was the belief that smoking was harmful to health. This result indicates that an education based intervention could be beneficial in helping smokers form the intention to quit, which is an initial step in quitting. As cessation services and medications are scarce in Jordan, efforts should be made to train physicians and other health professionals in educating the patients to the harms of smoking or referring them to trained professionals. Other reasons cited include not doing well in sports, and influence from a parent, spouse, or girlfriend/ boyfriend, thinking it was wrong or harmful for health as the person got older.

The effects of gender on smoking cessation have been inconsistent in the literature [15,27,30,31]. We did not find gender to be associated with the intention to quit or with having a previous quitting attempt even though literature reports greater pressure on women to quit [27], and a social discouragement of females to smoke cigarettes in Jordan [28] as well as in neighboring countries such as Lebanon [32] and Syria [33].

We did not find age to be associated with an intention to quit or with a quitting attempt, even though the belief that smoking was harmful as one got older was one of the reasons cited for the desire to quit and for quitting attempts in approximately a quarter of the population. A study examining smoking habits among university students in Jordan, revealed that two thirds of 186 student smokers expressed a desire to quit [6], which is higher than the rates found in this study that includes all adults of university age or older. Previous studies have been inconsistent with regard to association between age and intention to quit [15,19,26,34]

A previous quitting attempt was a predictor of willingness to quit in the multivariate models consistent with previous literature [15,18,35]. We examined a number of variables indicating addiction level and nicotine dependence [23] including cigarette consumption, time to first cigarette after waking up (before noon or after), cigarette one would most hate to give up (morning vs. other), how hard it is to refrain from smoking when not allowed, smoking when sick, and smoking more in the first 2 hours vs. rest of the day. The only variable associated with intention to quit in the adjusted models was heavy cigarette consumption (more than 10 per day) which was associated with a lower intention to quit. Finding difficulty to avoid smoking in nonsmoking areas was initially significantly associated with intention to quit and with a quitting attempt in the unadjusted model but was no longer associated in the multivariate model after adjusting for confounders. Fagan et al. [12] found an association between heavy smoking and a quitting attempt with daily cigarette smokers but not among nondaily smokers. The study also reported an association with time to first cigarette (within 30 minutes vs. not) in the daily smokers. We did not observe a significant difference in that variable. In this population of Jordanian adults, it seems that heavy smokers are less likely to want to quit indicating a higher addiction level. As nicotine dependence has been reported to significantly decrease quit attempts and smoking cessation [12,15,18,19]. Smokers with a high dependence level can be treated with interventions that can decrease the cigarette use level prior to quitting to give a better chance for a successful quit attempt later [15].

Participants who felt down or were bothered by something in the previous week were more likely to have had a previous quitting attempt, and those who were feeling down were also more likely to have an intention to quit in the next year in the adjusted model. Furthermore, those who felt like they had no friends were more likely to desire quitting in the next month. In this cross-sectional study we cannot establish if the feelings are what cause desire to quit or if the desire to quit is part of what is causing these feeling, but any intervention that will promote a successful cessation will have to take into consideration the psychological aspect.

The study findings also suggest that media messages against smoking might be effective in promoting an intention to quit, which is described as a prerequisite to quitting [15-17], as those who were exposed to such a message were more likely to have the intention to quit in the coming year. Media messages have been proven effective in reducing smoking rates in the US [36]. However, media’s message exposure was not a predictor of having an intention to quit in the coming month, which suggests that the message helped form a longer term intention rather than an immediate plan to change the behavior.

Participants in the medical field were more likely to have had a quitting attempt compared to those with professions outside the medical field, even though a previous study in Jordan [28] among 393 smokers employed in healthcare found similar rates of quitting attempts to that found in this study. This result also supports the usefulness of an education based intervention since professionals in the medical field are more educated with regards to potential harms of tobacco use. This education can in turn translate into an increased desire to quit.

Other variables in the survey that were explored as predictors but were not found to be significant include suffering from irritable bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease, heart diseases, or shortness of breath, family and friends cigarettes use, education level, graduating from public or private high school, and use of other addictive substances like alcohol and drugs (Data not shown).

Several limitations to this study can be described. The study was based on a convenience sample, thus we were unable to characterize non-participants. Causality cannot be inferred based on the crosssectional design. The generalizability of the results is limited to similar subpopulations in the Middle East and may not be applicable to other populations in different geographical areas or cultures. We did not control for employment or income which may affect the ability of a smoker to afford cigarettes and thus the intention to quit [12]. Economic status has been reported to affect the intention to quit in Syria [26]. We did, however, explore the type of high school that the participants graduated from (private or public) which is somewhat indicative of a socioeconomic status in Jordan.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this is the first study to our knowledge that examines predictors of intention to quit and perceptions of previous quitting attempts among a population of adults in Jordan. We found a high level of interest in quitting with the majority of the sample having had a quitting attempt (60%), and more than half of the population considering quitting in the next year (57%), underscoring the urgent need to develop interventions that can help these individuals quit. Predictors found to be significant in this study, including heaviness of smoking, media antismoking message exposure, medical education, previous quit attempts, and smoker’s mental health, should be considered in designing an effective intervention in this Middle Eastern country with high smoking rates.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Golda Hallett, Program Coordinator at the University of Houston College of Pharmacy, Department of Clinical Sciences and Administration, for undertaking the preliminary editing of this manuscript.

References

- CDC (2008) Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 2000-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 57: 1226-1228.

- Leung CM, Leung AK, Hon KL, Kong AY (2009) Fighting tobacco smoking--a difficult but not impossible battle. Int J Environ Res Public Health 6: 69-83.

- WHO, World Health Organization (2009) WHO Report on the Global tobacco epidemic, 2009

- Tan L, Tang Q, Hao W (2009) Nicotine dependence and smoking cessation. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 34: 1049-1057.

- Al-Omari H, Scheibmeir M (2009) Arab Americans' acculturation and tobacco smoking. J Transcult Nurs 20: 227-233.

- Haddad LG, Malak MZ (2002) Smoking habits and attitudes towards smoking among university students in Jordan. Int J Nurs Stud 39: 793-802.

- Rastogi T, Hildesheim A, Sinha R (2004) Opportunities for cancer epidemiology in developing countries. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 909-917.

- Dar-Odeh NS, Bakri FG, Al-Omiri MK, Al-Mashni HM, Eimar HA, et al. (2010) Narghile (water pipe) smoking among university students in Jordan: prevalence, pattern and beliefs. Harm Reduct J 7: 10.

- Azab M, Khabour OF, Alkaraki AK, Eissenberg T, Alzoubi KH, et al. (2010) Water pipe tobacco smoking among university students in Jordan. Nicotine Tob Res 12: 606-612.

- Kofahi MM, Haddad LG (2005). Perceptions of lung cancer and smoking among college students in Jordan. J Transcult Nurs 16: 245-254.

- Naddaf A (2007) The social factors implicated in cigarette smoking in a Jordanian community. Pak J Biol Sci 10: 741-744.

- Fagan P, Augustson E, Backinger CL, O'Connell ME, Vollinger RE, et al. (2007) Quit attempts and intention to quit cigarette smoking among young adults in the United States. Am J Public Health 97: 1412-1420.

- Redding CA, Rossi JS, Rossi SR, Prochaska JO, Velicer WF (2000) Health Behavior Models. The International Electronic Journal of Health Education 3: 180-193.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC (1992) In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol 47: 1102-1114.

- Feng G, Jiang Y, Li Q, Yong HH, Elton-Marshall T, et al. (2010) Individual-level factors associated with intentions to quit smoking among adult smokers in six cities of China: findings from the ITC China Survey. Tob Control 19: 6-11.

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, et al. (1991) The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 59: 295-304.

- Prochaska JO, Goldstein MG (1991) Process of smoking cessation. Implications for clinicians. Clin Chest Med 12: 727-735.

- Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q, Yong HH, McNeill A, et al. (2006) Individual-level predictors of cessation behaviours among participants in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 15: 83-94.

- Hyland A, Li Q, Bauer JE, Giovino GA, Steger C, et al. (2004) Predictors of cessation in a cohort of current and former smokers followed over 13 years. Nicotine Tob Res 6 Suppl 3: S363-369.

- Sussman S, Dent CW, Severson H, Burton D, Flay BR (1998) Self-initiated quitting among adolescent smokers. Prev Med 27: 19-28.

- Peters RJ Jr, Kelder SH, Prokhorov A, Amos C, Yacoubian GS Jr, et al. (2005) The relationship between perceived youth exposure to anti-smoking advertisements: how perceptions differ by race. J Drug Educ 35: 47-58.

- Peters RJ, Kelder SH, Prokhorov A, Springer AE, Yacoubian GS, et al. (2006) The relationship between perceived exposure to promotional smoking messages and smoking status among high school students. Am J Addict 15: 387-391.

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO (1991) The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict 86: 1119-1127.

- Warren CW, Jones NR, Eriksen MP, Asma S, Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) collaborative group (2006) Patterns of global tobacco use in young people and implications for future chronic disease burden in adults. Lancet 367: 749-753.

- Mermelstein R, Colby SM, Patten C, Prokhorov A, Brown R, et al. (2002) Methodological issues in measuring treatment outcome in adolescent smoking cessation studies. Nicotine Tob Res 4: 395-403.

- Maziak W, Hammal F, Rastam S, Asfar T, Eissenberg T, et al. (2004) Characteristics of cigarette smoking and quitting among university students in Syria. Prev Med 39: 330-336.

- Haddad LG, Petro-Nustas W (2006) Predictors of intention to quit smoking among Jordanian university students. Can J Public Health 97: 9-13.

- Shishani K, Nawafleh H, Jarrah S, Froelicher ES (2010) Smoking patterns among Jordanian health professionals: A study about the impediments to tobacco control in Jordan. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs [Epub ahead of print].

- Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Rastam S, Asfar T, Mzayek F, et al. (2006) The tobacco epidemic in Syria. Tob Control 15: 24-29.

- Hublet A, Maes L, Csincsak M (2002) Predictors of participation in two different smoking cessation interventions at school. Health Educ Behav 29: 585-595.

- Garrison MM, Christakis DA, Ebel BE, Wiehe SE, Rivara FP (2003) Smoking cessation interventions for adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 25: 363-367.

- Tamim H, Terro A, Kassem H, Ghazi A, Khamis TA, et al. (2003) Tobacco use by university students, Lebanon, 2001. Addiction 98: 933-939.

- Maziak W, Rastam S, Eissenberg T, Asfar T, Hammal F, et al. (2004) Gender and smoking status-based analysis of views regarding waterpipe and cigarette smoking in Aleppo, Syria. Prev Med 38: 479-484.

- Venters MH, Kottke TE, Solberg LI, Brekke ML, Rooney B (1990) Dependency, social factors, and the smoking cessation process: the doctors helping smokers study. Am J Prev Med 6: 185-193.

- Wong DC, Chan SS, Ho SY, Fong DY, Lam TH (2010) Predictors of intention to quit smoking in Hong Kong secondary school children. J Public Health (Oxf) 32: 360-371.

- Ibrahim JK, Glantz SA (2007) The rise and fall of tobacco control media campaigns, 1967 2006. Am J Public Health 97: 1383-1396.

Citation: Abughosh S, Wu IH, Hawari F, Peters RJ, Yang M, et al. (2011) Predictors of Intention to Quit Cigarette Smoking among Jordanian Adult. Epidemiol 1:103. DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000103

Copyright: © 2011 Abughosh S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16456

- [From(publication date): 10-2011 - Nov 19, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 11544

- PDF downloads: 4912