Research Article Open Access

Predictors of HPV Vaccine in College Men

Purvi Mehta* and Manoj SharmaHealth Promotion & Education, University of Cincinnati, Teachers College 527 C, Cincinnati, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Purvi Mehta

Graduate Research and Teaching Assistant

Health Promotion & Education

University of Cincinnati

Teachers College 527 C, PO Box 210068

Cincinnati, OH45221-0068, USA

Tel: (513) 556- 3878

Fax: (513) 556-3898

E-mail: mehtapi@mail.uc.edu

Received date: November 07, 2011; Accepted date: December 08, 2011; Published date: December 10, 2011

Citation: Mehta P, Sharma M (2011) Predictors of HPV Vaccine in College Men. J Community Med Health Edu 1:111. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000111

Copyright: © 2011 Mehta P, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Objective: Humanpapilloma virus (HPV) is a common sexually transmitted infection (STI), leading to cervical and anal cancers. Annually, 6.2 million people are newly diagnosed with HPV and 20 million are currently diagnosed. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 51.1% of men carry multiple strains of HPV. Recently, HPV vaccine was approved for use in boys and young men to help reduce the number of HPV cases. The purpose of this study was to use health belief model (HBM) to predict acceptance of HPV vaccine in college men between the ages of 18-24 years.

Design: Cross sectional design.

Method: Perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action and self-efficacy from the health belief model were assessed in determining whether men would take the vaccine. A panel of six experts helped in establishing the face and content validity of the instrument. Internal consistency, test retest reliability, and construct validity were tested and found to be acceptable. Multiple regression modeling was done to ascertain relationships between HBM predictors and acceptability of the vaccine in men.

Results: Self-efficacy, cues to action, and perceived susceptibility were significant predictors for taking the HPV vaccine (adjusted R 2 = 0.480).

Conclusion: HBM is a robust model to predict HPV vaccine acceptability in college men. Health education interventions can be designed based on HBM to enhance acceptability of HPV vaccine in college men. Recommendations for future research are discussed.

Keywords

HPV; College men; HPV vaccine; Vaccine acceptability

Introduction

Humanpapilloma virus (HPV) is a common sexually transmitted disease/infection (STD/STI). The virus attacks the skin and mucous membranes of humans and spreads from human to human through sexual contact. There are hundreds of different strains, but only forty are known to cause disease through mainly sexual contact. Of these forty, there are four strains in particular that are of prime interest: HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] [1] approximately 50% of men and women that are sexually active will have contracted an HPV infection in their lifetime. Annually, 6.2 million people are newly diagnosed with HPV and 20 million currently are diagnosed in the United States. Data indicates that gay and bisexual men are more likely to be diagnosed with HPV. These groups along with those that have HIV/AIDS were found to be 17 times more likely to develop anal cancer. The latter group tends to obtain severe cases of genital warts than other men.

It was also found that 51.1% of men tended to carry multiple strains of HPV [1]. Approximately 73% of men have been infected with HPV [2]. These infections have led to approximately 93% of anal cancers, 63% oropharyngeal cancers, and 36% of penile cancers. With regard to gay and bisexual men, prevalence of HPV is 60% in men without HIV, and close to 90% in those with HIV. Rates of anal cancer were also found to be higher in men having sex with men. Taking the HPV vaccine, serves as a preventative measure, especially when administered prior to sexual debut. Unfortunately, limited knowledge of HPV associated health issues for men was found by Reiter et al. [2].

Currently, Gardasil is an approved vaccine that helps guard against 90% of genital warts in males [3]. Gardasil is given in three shots over the course of six months. Males between the ages of nine and 26 are approved to take the vaccination. It has been noted that men who have not had sex and young men who have sex with men benefit the most from the vaccine. Men who have had sex with a female do not benefit has much, as the likelihood of an HPV infection is higher.

In a recent review, 74%-78% acceptability of the vaccine among college males was found [4]. Several studies within the review found a relationship between vaccine acceptability and males that believed sexual partners, parents or physicians would encourage taking the vaccine, having a firm belief in the general importance of the vaccine, knowledge and awareness of HPV, perception of being at high risk, and belief in vaccinations. Very limited literature exists on the role of health belief model constructs with men but some is available with regards to women [5]. Adult women and adolescents indicated high likelihood of HPV exposure and cervical cancer, which was associated to higher acceptability of the vaccine [6]. Perceived severity was only found with regards to cervical cancer, but no relationship with acceptability of the vaccine. No significant values were found for perceived effectiveness. Due to limited literature, correlates of vaccine acceptability among a high risk group need to be examined for future preventative purposes.

A few studies utilizing a quantitative approach have explored correlates of HPV vaccination in men. Acceptability among a national sample of gay and bisexual men was high [7]. In particular, 73% were aware of the vaccine, 74% willing to take it. Recommendations from the doctor, five or more sexual partners, perceived greater severity of HPV-related diseases, and perceived higher levels of effectiveness were motivators in acceptance of the vaccine.

Gerend and Barley found a moderate level of interest in taking the vaccine, regardless of the group (self-protection versus self-protection and partner protection about HPV and the vaccine) they were assigned to [8]. Factors related to taking the vaccine were: sexual activity, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived costs, selfefficacy, and perceived norms. These correlates are analogous to those identified in women; thus suggesting predictors of vaccine acceptability tend to be similar regardless of gender.

Ferris, Waller, Miller, Patel, Price, Jackson, and Wilson also examined HPV vaccine acceptability by giving participants a one page HPV and HPV vaccine information sheet, followed by a 29 item questionnaire [9]. Unlike the previous study, this one focused on demographic, sexual and vaccine-related variables. Results showed higher education, Hispanic ethnicity, wearing a seat belt most of the time, regular tobacco use, sexual inactivity, more than 10 sexual partners, importance of getting oral sex, familiarity with HPV, and extreme importance of receiving the vaccine. This study indicated men with high-risk health behaviors, higher education, and awareness of HPV were more likely to take the vaccine.

Hernandez, Wilkens, Shvetsov, Goodman, Ning, and Kaopua surveyed college men between the ages of 18 and 79 on awareness, attitudes and intentions to vaccinate [10]. Results indicated side effects, efficacy, safety, and costs as main predictors in vaccination. Cost issues were of major concern for men 18-26 years old, but were still more likely to get vaccinated than other age groups. Of the 18-26 year olds, men having sex with men had a higher intention of vaccination versus heterosexual men. Costs and sexual history are crucial determinants in intentions towards vaccination.

Based on available literature, the health belief model was utilized as the theoretical backdrop for this study [11,12]. Perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action and self-efficacy in getting vaccinated for the HPV vaccine were tested. Perceived susceptibility is the belief the person may acquire HPV, perceived severity is that HPV is a serious disease with negative consequences; perceived benefits are the belief in the advantages of suggested prevention methods namely HPV vaccine. Perceived barriers are things such as costs and side effects that would prevent them from taking the vaccine. Cues to action are factors that will motivate individuals to take the vaccine and self-efficacy is the confidence that a person has in her or her ability to take the HPV vaccine.

Limited literature exists on the role of these constructs with men but some is available with regards to women [5]. Adult women and adolescents indicated high likelihood of HPV exposure and cervical cancer, which was associated to higher acceptability of the vaccine [6]. Perceived severity was only found with regards to cervical cancer, but no relationship with acceptability of the vaccine. No significant values were found for perceived effectiveness. A few studies have been conducted with parents and physicians regarding HPV vaccination with girls, and a few regarding women’s awareness and acceptability. Results indicated increasing awareness of HPV, informing costs and benefits associated with the vaccine, and perceived susceptibility. Based on this information, it is crucial to obtain a further understanding of knowledge, awareness, and Health Belief Model based predictors related to HPV and its vaccination in men. The purpose of the study was to determine predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability among college men based on health belief model.

Materials and Methods

Design

The study utilized a cross-sectional study design. The HPV vaccine acceptability was the dependent variable and constructs of health belief model (HBM), namely, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action and self-efficacy in getting vaccinated for the HPV vaccine were the independent variables. The chief advantage of the cross sectional design is that it is relatively inexpensive and provides a snap shot of the reality. The chief disadvantage of this design is that it cannot establish causality as the temporal sequence is not studied in this design.

Instrumentation

A valid and reliable five point Likert scale survey based on the health belief model (HBM) was developed by the researcher. Face and content validity were established by a panel of six experts (two HBM experts, two target population experts, and two HPV vaccine experts) in two rounds. Internal consistency of subscales was established by Cronbach’s alpha; values between 0.70 and 0.90 were obtained. These are depicted in Table 1. Reliability of the survey was determined through a test-retest procedure. Test retest reliability coefficients were computed in a sample of 30 participants; r values between 0.60-0.80 were obtained. These are depicted in Table 2.

| Constructs | Alpha levels |

|---|---|

| Perceived Susceptibility | 0.900 |

| Perceived Severity | 0.753 |

| Perceived Benefits | 0.585 |

| Perceived Barriers | 0.920 |

| Cues to Action | 0.706 |

| Self Efficacy | 0.761 |

| Knowledge | 0.705 |

Table 1: Internal Consistency Reliability Coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) for Perceived Susceptibility, Perceived Severity, Perceived Benefits, Perceived Barriers, Cues to Action, Self Efficacy and Knowledge (n =222)

| Construct | r | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Susceptibility | 0.819 | 0.003 |

| Perceived Severity | 0.603 | 0.006 |

| Perceived Barriers | 0.853 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Benefits | 0.652 | 0.050 |

| Cues to Action | 0.571 | 0.009 |

| Self Efficacy | 0.647 | 0.002 |

| Knowledge | 0.624 | 0.003 |

Table 2: Test-retest Reliability Coefficients for Perceived Susceptibility, Perceived Severity, Perceived Benefits, Perceived Barriers, Cues to Action, Self Efficacy and Knowledge (n=30)

The first two questions assessed if participants had heard of HPV and the HPV vaccine. Responses were true, false, and do not know. Knowledge was measured in the next six questions with answer options of true or false. Items such as: HPV is a common virus that can be passed on through sexual contact and HPV can cause health problems, such as genital warts were asked. Perceived susceptibility was measured in the next three questions on a five point Likert scale, with the total possible score range from zero (all strongly disagree) to 12 (all strongly agree). Due to my sexual behaviors I am at higher risks for HPV infections or cancers, and I have had more than 1 sexual partner, placing me at risk for getting an HPV infection, were examples of items asked for this construct. The next three questions asked about perceived severity with items such as: HPV can cause health problems such as genital warts, HPV can cause serious diseases. A total possible range of scores were zero (all strongly disagree) to 12 (all strongly agree). Perceived barriers were addressed in the following three questions with items such as: I cannot afford the HPV vaccine ($375), and I do not have access to getting the 3 shot series of the HPV vaccine. A total possible range of scores between zero (strongly disagree) to 12 (strongly agree). Cues to action were measured by five questions with items such as: I have been advised by friends about the benefits of taking the vaccine, my friends have gotten the vaccine, and I plan on getting it as well, and I would like to take the HPV vaccine to take better care of my sexual health. A total possible range of scores between zero (all strongly disagree) to 20 (all strongly agree). Perceived benefits were the following questions. A total possible range of scores between zero (all strongly disagree) to 12 (all strongly agree). Self-efficacy was measured in the following three items with items such as: I am confident I can take the HPV vaccine, or I am confident I can complete all 3 doses of the HPV vaccine. A total possible range of scores between zero (all strongly disagree) to 12 (all strongly agree). This was then followed by a question asking whether participants would take the vaccine or not, with a possible score rage of 0 (strongly disagree) to four (strongly agree). Demographic questions were asked regarding age, sexual orientation, year in school, marital status, and participation in sexual intercourse. No information regarding HPV and its vaccination were stated on the survey. Participants were asked to answer questions to their best ability.

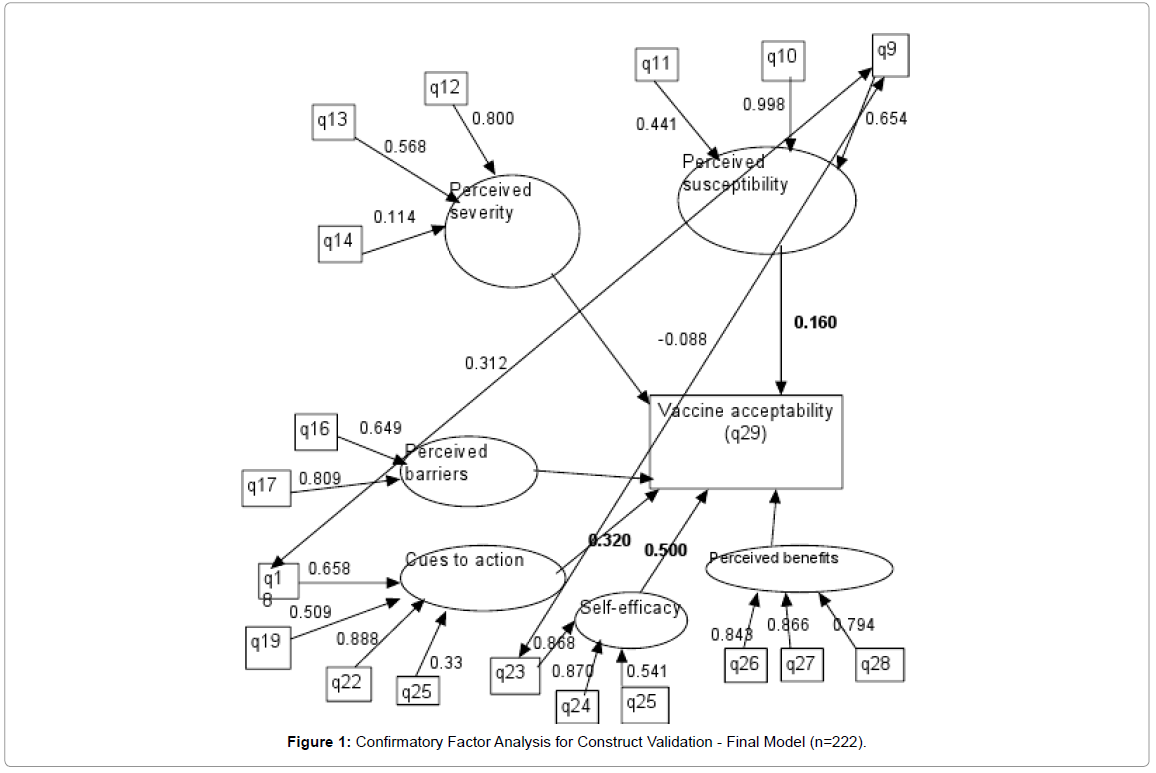

Confirmatory factor analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted after 222 samples were collected to establish construct validity of the subscales. The dependent variable (whether they would take the vaccine or not) was coded as a categorical variable; no =0, maybe = 1, yes= 2. Missing variable issues were taken care of by coding for them in the model with “missing is.” Perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action and self-efficacy were coded f1-f6, respectively. The output was standardized and a modification index at a 3.84 level was also obtained to help refine the model.

The initial model obtained was not a good fit due to a chi-square value of (df=40, p=.000) 135, RMSEA = 0.106, and a CFI=0.631. Regression results deemed F1, F4, and F5 to be significant predictors of vaccine acceptability. The significant predictors were: perceived susceptibility, cues to action, and self-efficacy. Correlations between factors were significant but remained in the low to moderate (-.023 to 0.24); f1 with f4, f5; f2 with f3, f4; f3 with f5, f6; f4 with f5; f5 with f6, were the respective correlations. Proportion of variance accounted for were moderate to high (42%-80%) except for a few indicators with low levels (1%-32%). Modification indices gave suggestions for improvement in the model. Based on these suggestions, q15 and q20 were eliminated from the survey. In addition q19 was correlated with q18 and q23.

Results from the model adjustments gave us a good fit model, with a chi-square value of (df=37, p=.087) 49.17, CFI=0.952, and a RMSEA=.039. These are all good indicators of good fit model. Parameter estimates for loadings slightly increased compared to the initial model. Loadings (standardized) on each factor vary from moderate to high: range of 0.114 to 0.99. Modifications to the initial model raised the factor loadings. An ideal loading varies from 0.6 to 0.9, indicating a few weak indicators are present: q11, q14, q25. This may pose a problem with questions being similar in nature. Correlations with factors were significant at an alpha level of .05 for the following: f1 with f4, f5; f2 with f3, f4; f3 with f5, f6; f4 with f5; f5 with f6. These correlations were similar to those found in the initial model. Regression results remained the same as the initial model. Proportion of variance (R2) values increased from the initial model, with a majority of variance ranging from 42%-99% (Figure 1).

Participants

Participants were males, 18 years or older, attending a large size Midwestern University. Both undergraduate and graduate students who met the eligibility requirements were recruited. A confidence interval of 95%, p =0.05, a minimum of 200 participants had to be recruited Recruitment from general education classes, gathered a total of 222 participants. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. No incentives were given for participation. It is important to note that the research was conducted after the release of the vaccine.

Procedures

Approval from the IRB of the University was obtained prior to the study. Administration of the survey was conducted at the end of class time. Clipboards and pens were provided for completion of the survey. Participants were asked to complete the survey to their best ability. Anonymity and confidentiality of responses were assured to them. Once surveys were completed, participants slid the surveys into a manila envelope. Survey administration was conducted over a period of one month to obtain the predetermined sample size.

Data analysis

All data were analyzed in PASW (Predictive Analytics SoftWare), formerly SPSS, Version 18. Descriptive statistics, along with stepwise multiple regression was conducted to determine what factors affect vaccine acceptability. The apriori criteria of probability of F to enter the predictor in the model was chosen as less than and equal to 0.05 and for removing the predictor as greater than and equal to 0.10. Health belief model construct variables served as independent variables and whether participants would take the vaccine was the dependent variable. This allowed us to account for significant proportion of variance between the chosen constructs within the health belief model and taking the vaccine. Alpha levels were set to 0.5 to determine significance.

Results

Descriptive statistics indicated a majority of the participants were single, sexually active, Caucasian males between the ages of 18 and 54, attending their sophomore year of college. Table 3 summarizes some key demographic characteristics of the study population. With regard to sexuality, 93.2% reported to be heterosexual, 2.3% were homosexual, and 1.4% were bisexual. When asked whether they would take the vaccine, 43.2% were neutral, 6.3% strongly agreed, 20.7% agreed, 15.8% disagreed, and 13.5 % strongly disagreed.

| Variable | n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 222 | 18 | 54 | 20.28 | 3.42 |

| Year in College | 222 | 1 | 5 | 2.25 | 1.09 |

Table 3:Summary of the Demographic Characteristics of the Sample of College Men

Percentage of college men who had heard of HPV was 81.1% while 3.6% were unsure of what it was. After missing variables were deleted, there were 217 responses for the construct related questions. With regard to the HPV vaccine, 52.7% were aware of its existence while 11.7% were unsure. Observed range of scores for perceived susceptibility was zero to 11, cues to action was zero to 13, self-efficacy was zero to 12, perceived barriers was zero to eight, and perceived benefits was two to 12. Average scores for perceived benefits were 7.05 units +/- 2.22, cues to action were 5.22 units +/- 3.47, self-efficacy for taking the vaccine were 5.96 units +/- 2.63, perceived severity were 8.70 units +/- 2.11, perceived barriers were 6.00 units +/- 2.15, perceived susceptibility were 3.62 units +/- 2.82. Of the 222 male participants, 82.9% were sexually active. Summary of the constructs of health belief model are presented in Table 4.

| Variable | n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | St. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Susceptibility | 220 | 0 | 11 | 3.62 | 2.82 |

| Perceived Severity | 221 | 1 | 12 | 8.70 | 2.11 |

| Perceived Barriers | 222 | 0 | 8 | 4.04 | 2.02 |

| Perceived Benefits | 222 | 2 | 12 | 7.05 | 2.22 |

| Cues to Action | 222 | 0 | 13 | 3.26 | 2.92 |

| Self-Efficacy | 220 | 0 | 12 | 5.96 | 2.63 |

Table 4: Summary of the Scores of Constructs of the Health Belief Model in a Sample of College Men

Multiple regression results indicated self-efficacy for taking the vaccine (p=0.000), cues to action (p=0.001), and perceived susceptibility (p=0.002) held a significant positive relationship towards vaccine acceptability. The model had an adjusted R2 of 0.480, which indicated that these three predictors accounted for 48% variance regarding whether participants would take the vaccine. The parameter estimates are summarized in Table 5. No significant relationships were seen for perceived benefits, perceived severity, perceived barriers or knowledge.

| Source | Unstd.Coeff. | Std. Error | Std. Coefficients Beta | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (constant) | 0.181 | 0.143 | 1.262 | 0.208 | |

| Self Efficacy | 0.211 | 0.023 | 0.515 | 9.281 | 0.000 |

| Cues to Action | 0.069 | 0.020 | 0.190 | 3.483 | 0.001 |

| Perceived | |||||

| Susceptibility | 0.063 | 0.020 | 0.163 | 3.082 | 0.002 |

Table 5: Parameter Estimates from the Final Regression Model for Self Efficacy, Cues to Action and Perceived Susceptibility Scores (adjusted R2 = 0.436)

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to determine the role of the health belief model in predicting HPV vaccine acceptability among college males. Results of this study found that self-efficacy for taking the vaccine; cues to action, and perceived susceptibility were able to explain significant variance in whether males would take the HPV vaccine. These constructs were also significant predictors in HPV vaccine acceptability in the study conducted by Gerend and Barley [8].

A majority of the males were Caucasian, heterosexual, males about 20 years old. Awareness of the HPV was seen in most participants (81%), while only half were aware of the vaccine. A small percentage was not sure of HPV or the HPV vaccine. This is a significant finding from the perspective of health education. This signifies that more health education efforts need to be designed toward this population in creating awareness about the vaccine. It is worth noting that a large majority of the participants were sexually active but awareness of HPV in men was fairly low. Higher levels of awareness would have altered levels of HPV vaccine acceptability. With regards to the constructs of the Health Belief Model, mean scores were in the middle of possible range. Once again this signifies that health education efforts can enhance these scores in this population which would simultaneously indicate behavior change. Unfortunately, not much can be stated in concrete terms due to the limited literature available on the role of health belief model constructs5. This study lends credence to the applicability of the health belief model as an educational tool in designing interventions.

Agreeing towards taking the vaccine was only seen with 27% of the participants, which is lower than the 74%-78% reported by Liddon, Hood, Wynn, and Markowitz [4]. This may be due to sample size limited to one institution. Gerend and Barley had also found sexual activity to be a predictor in HPV vaccine acceptability [8]. Based on our findings, a majority of the participants were sexually active but higher rates of acceptance were not found. Implementation of an educational intervention on HPV and HPV vaccination can alter these findings.

Our findings suggest that increasing self-efficacy, perceived susceptibility and cues to action will lead college men to take the HPV vaccine course. Based on the results, participants believed they were prone to HPV. Showing the impacts of the disease through the constructs of the health belief model will enable them to take the vaccination. Overall, the health belief model served as a robust model in predicting HPV vaccination behavior among college men. Findings suggest a need for intervention programs focusing on increasing selfefficacy, educating males about HPV, and providing cues to take the vaccine.

Limitations of the Study

Results were based on a self-report survey, which could have included both participant bias and dishonesty. In addition, participants may not have full understood or may have misinterpreted questions that might have misrepresented the responses. This study utilized a cross-sectional design, which supplied us with information for a particular point in time. Answers might have varied if the survey was given at a different time. Also, since this was a cross-sectional study nothing can be said about the time sequence of the associations found in this study. In addition, results from the confirmatory factor analysis indicated a few slightly weak indicators. Had they been rephrased, it might have strengthened the indicator.

Location served as another limitation in the study. The large Midwestern University was the only institution where participants were recruited. Participants from surrounding institutions may have altered or could have confirmed the results of the study. In addition, the large Midwestern University’s location in the Midwest could have affected the results. Regional differences could have added to the obtained results. Finally, the survey used for the study was newly constructed.

Implications for Practice

Based on the results, an intervention focused on increasing awareness and acceptability of HPV and the HPV vaccine need to occur. The Health Belief Model was shown to be a robust model in carrying out an educational program. Emphasizing males’ susceptibility towards HPV, finding motivators in accepting the vaccine, and building their confidence in taking the vaccine are necessary components for the facilitation of HPV vaccines. While self-efficacy, cues to action, and perceived susceptibility were the significant predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability, the remainder constructs of perceived barriers, perceived benefits, and perceived severity, can also be employed in the program. This would enable a higher level of knowledge for participants which would lead to a higher acceptability of the vaccine.

Recommendations for Future Research

A need exists for future studies to determine factors leading towards HPV vaccination in men. Future studies should expand the study to multiple institutions, in order to determine the perceptions of HPV vaccination in men. Studies should also consider looking into men of various races/ethnicities, as their awareness and knowledge of HPV may differ. Homosexual and bisexual men must also be targeted in future studies, as literature has indicated a higher benefit by taking the vaccination. It would also be of value to survey men in high school or junior high school. This would be important, as the vaccination has a better impact when taken before sexual debut.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Genital HPV infection: Fact sheet. CDC website. Accessed August 1, 2011.

- Reiter PL, Brewer NT, Smith JS (2010) Human papillomavirus knowledge and vaccine acceptability among a national sample of heterosexual men. Sex Transm Infect 86: 241-246.

- Gever J (2011) FDA approves vaccine for men and boys. Medpage Today website.

- Liddon N, Hood J, Wynn BA, Markowitz LE (2010) Acceptability of Human Papillomavirus vaccine for males: A review of literature. JA dolesc Health 46: 113-123.

- Brewer NT, Fazekas KI (2007) Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: A theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med 45: 107-114.

- Mays RM, Zimet GD, Winston Y, Kee R, Dickes J, et al. (2000) Human papillomavirus, genital warts, Pap smears, and cervical cancer: knowledge and belief of adolescents and adult women. Health Care Women Int 21: 361-374.

- Reiter PL, Brewer N, McRee A, Gilbert P, Smith JS (2010) Acceptability of HPV vaccine among a national sample of gay and bisexual men. Sex Transm Dis 37: 197-203.

- Gerend MA, Barley J (2009) Human Papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among young adult men. Sexually Transm Dis 36: 58-62.

- Ferris DG, Waller JL, Miller J, et al. (2009) Variables associated with Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptance by men. J Am Board Fam Med 22: 34-42.

- Hernandez BY, Wilkens LR, Thompson PJ, et al. (2010) Acceptability of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccination among adult men. Hum Vaccin 6: 467-475.

- Becker MH (1974) The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monographs 2: 324-473.

- Sharma M, Romas JA (2008) Theoretical foundations of health education and health promotion. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers: 69- 90.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14129

- [From(publication date):

December-2011 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9570

- PDF downloads : 4559