Pattern and Significance of Ocular Injuries Associated with Orbito- Zygomatic Fractures

Abstract

Introduction: The face, orbit, and eyes have a relatively

prominent position in the human body making

this area more susceptible to trauma. A variety

of ophthalmic injuries associated with mid-facial

fractures has been reported in the literature [1]. Motor-

vehicle accidents, as sault, falling down injuries,

occupational, and sport accidents are generally considered

as common etiologies of maxillofacial fractures

[2].

Zygomatic fractures are the most common facial

fractures second only to nasal fractures and these

fractures are also the most commonly occurring fractures

of the orbit [3]. There is a recognized association

between orbitozygomatic fractures and ocular

injuries. The reported incidence of ocular injuries in

patients with orbital fractures varies widely, ranging

from 2.7% to 90% [1,4]. Al-Qurainy et al. developed

criteria for appropriate referral to an ophthalmologist.

The authors proposed the acronym “BAD ACT,”

to represent Blowout, Acuity, Diplopia, Amnesia, and

Comminuted Trauma, as a method for easy recall.

However, the system is not commonly used in clinical

practice [5]. The severity of an injury is related to

the site of the fracture and direction of the incoming

force. The outcome may range from mild injury

such as sub-conjunctival hemorrhage (SCH) to severe

damage like globe rupture or permanent visual loss

[1,4].

Early diagnosis of potentially serious ophthalmic injuries

is paramount not only in minimizing long-term

complications of midfacial fractures but also from

a medico-legal standpoint. The management of the

ophthalmic injuries must be considered as the first

priority. Repairing the fractures before treatment of

ophthalmic injuries may further compromise visual

outcomes, leading to visual loss [5].

Patients and Methods: This is a retrospective study

of patients presenting with orbitozygomatic bone

fractures admitted to Maxillofacial Surgery Department

at King Fahad Hospital in Almadinah Almunawara,

Saudi Arabia from 2012 to 2017. Patients with

isolated zygomatic arch fractures or concomitant

midfacial fractures were excluded from the study.

Fractures were diagnosed clinically. The extent of the

bony injury was confirmed with computerized tomographic

scans (CT). Patient demographics, date of

injury, date of presentation to the hospital, fracture

etiology, brain injuries status and clinical ocular signs

were recorded.

All patients were examined by the ophthalmologist

preoperatively, and if needed were also followed up

postoperatively. On the basis of clinical examination

and pre-treatment, radiograph/CT scan result, the

study population was divided into 3 subgroups based

on the extent of the bony injury.

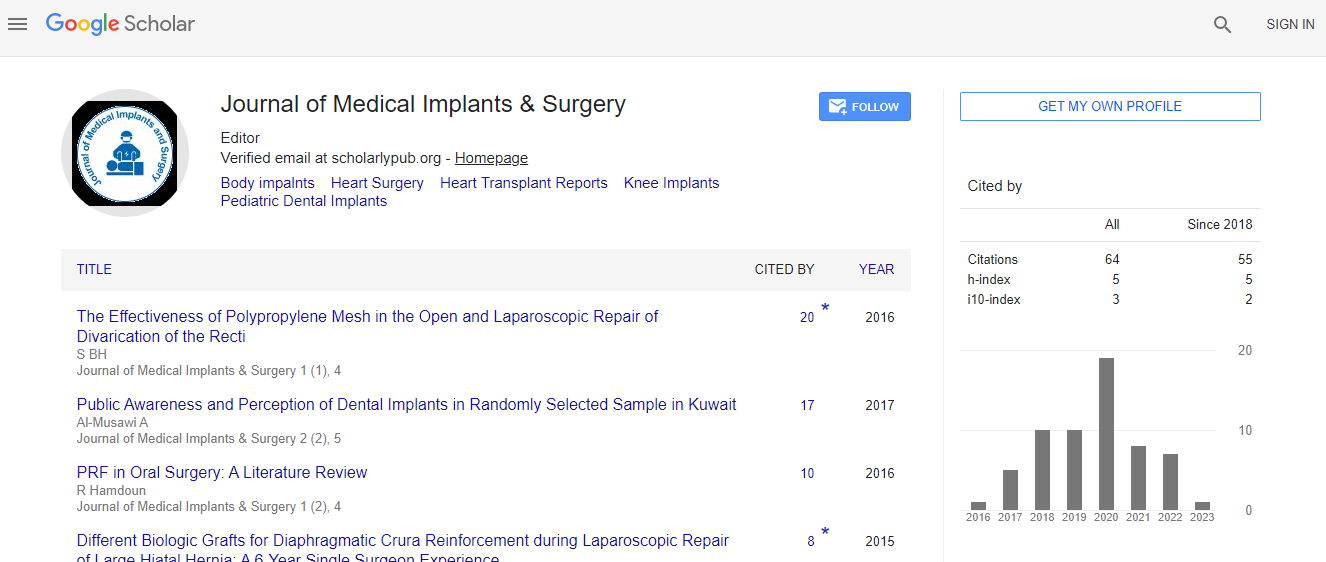

Results: The study population included 156 patients

(142 male and 14 female). There was a peak in incidence

for adult compared to female accounting for

91% of the fractures as shown in Table 1.

Road traffic accident was the most commonly documented

mechanism of injury, accounting for 79.5%

(n=124) of the fractures, followed by fall down injuries

(18%, n=11.5), explosion (0.6%, n=1), assault

(4.5%, n=7), and gunshot (0.6%, n=1). This is summarized

in Table 2.

Variables Frequency Percentage (%)

Road traffic accident 129 82.7

Explosion 1 0.6

Assault 7 4.5

Fall down 18 11.5

Gun shot 1 0.6

Total 156 100

Table 2: Details about road traffic accidents.

Group-1 (“simple” fractures) accounted for 67.3%

(n=105) of the patients, Group-2 (“comminuted”

fractures) accounted for 23.7% (n=37), and Group-3

(“orbital blowout”) for 9% (n=14). All orbitozygomatic

fractures were unilateral.

There were 2 ocular findings in Group-1 (1.9%). Complete

visual loss occurred in one patient. The other

patient had mild diplopia. There were 15 ocular findings

(n=37, 40.5%) in Group-2.

Resolution occurred in 10 patients. Three patients

had permanent visual loss. One has mild exophthalmos

and one patient presented with oculomotor

nerve neuropathy. There were 7 ocular findings

(n=14, 46.6%) in Group-3.

Resolution occurred in 6 patients. One had persistent

non disabling diplopia at the extremes of visual field.

The data is represented in both Table 3 and 4.

Variables Sample size (n) Percentage (%)

Zygomatico-maxillary complex fracture 3 7

23.7

Isolated orbital floor fracture 14 9

Simple non comunuted zygomatico-maxillary fracture

105 67.3

Total 156 100

Table 3: Subgroups of zygomatic fractures frequency.

Category of ocular injury Type of zygomatic fracture

Total

Zygomatico-maxillary complex fracture Isolated

orbital floor fracture Simple noncomunuted zygomatico-

maxillary fracture

Blindness 3 0 1 4

Free 22 8 103 133

Occulomotor injury 5 0 0 5

Rupture globe 1 0 0 1

Enophthalmos 5 0 0 5

Diplopia 0 6 1 7

Exfliated globe 1 0 0 1

Total 37 14 105 156

Table 4: Frequency of ocular injury associated with

zygomatic fracture.

Discussion

Analysis of the data from this retrospective study allows

examination of demographic patterns, etiology

of injuries, and highlights the ocular morbidity associated

with orbitozygomatic trauma. There were no

patients in the study population presenting with bilateral

orbitozygomatic fractures.

Pan facial and midfacial/nasoethmoid fractures were

excluded in order to examine ocular morbidity specifically

related to orbitozygomatic fractures. Similar

to other studies addressing maxillofacial trauma,

there was a peak in incidence for orbitozygomatic

fractures in adult males compared to children as

shown in Table 1 [7]. Road traffic accident was the

most commonly documented mechanism of injury in

this study, accounting for 82.7% of patients, followed

by fall down (11.5%), and assault (4.5%). This corresponds

with other urban trauma studies [8].

The etiology of injury varies geographically: in Western

countries with large urban populations, alcohol

related assault remains the primary etiologic factor

in maxillofacial trauma. However, motor vehicle accidents

predominate in many developing countries, in

the absence of seat belt legislation and where alcohol-

related assault is uncommon [9].

The reported incidence of ocular injuries in patients

with orbital fractures varies widely, ranging from

2.7%1 to 90% [2]. The incidence in this study was

14.7%, which is consistent with many other studies.

Lower levels reported where ophthalmologic input is

absent or only sporadic may indicate that some ocular

findings were undetected [3]. On the other hand,

variation in reported incidence between studies may

represent differences in inclusion criteria.

For example, the 90.6% incidence reported by Al-

Qurainy et al. includes subconjunctival hemorrhage

as ocular pathology. This is not counted as a significant

ocular finding in many other studies, including

this study. Furthermore, Al-Qurainy’s study includes

all midfacial/ nasoethmoid fractures that were excluded

in this study [3].

BAD ACT, scoring system proposed by Al-Qurainy et

al. to predict ocular injury risk and therefore allow

appropriate referral, is not widely used in clinical

practice [6,7]. An estimation of the ocular injury risk

associated with specific orbitozygomatic fractures

may be useful for assessment of risk. Based on data

from this study, “simple fractures” have 2% risk of

concomitant ocular finding or injury. However this

complication arises from severe brain injuries associated

with simple orbito-zygomatic bone fracture.

Comminuted fractures have 40.5% risk (over one

third); and blowout fractures a 42.8% risk (over one

thirds of patients). We postulate that the varying

incidence of ocular finding or injury in the fracture

groups (“simple” “comminuted’’, “blow out’’) is related

to the mechanism of injury. The higher velocity

of impact required to generate a comminuted orbitozygomatic

fracture leads to an increased number of

ocular findings and injuries in this group when compared

with the “simple” fracture group.

The mechanism of injury in orbital blowout fractures

has been a source of discussion, but may explain the

increased incidence of ocular findings and injuries in

the “Blow Out” group. There are 2 main theories, as

follows:

Table 5: Illustration of the level of significance of

Group-1, 2 and 3.

We propose that orbitozygomatic fractures be divided

into “simple”/ “noncomminuted” fractures, “comminuted”

fractures, and “blowout” fractures, based

on clinical and conventional radiographic findings. CT

scan should be used to confirm the extent of bony

injury, allowing estimation of ocular injury risk.

Ophthalmology consultation is recommended for

Group-2 and 3 presenting with orbitozygomatic fractures.

Where constraints in available ophthalmology

resources exist, preferential referral for comminuted

and blowout fractures is recommended based on the

high incidence of ocular findings and injuries in these

patient subgroups.

Statistical analysis: This study revealed statistically

significant made by Group-2 and 3 as predictor for

ocular injury as summarized in Table 5.

Analysis of predictors (head injuries and gender) as

a contribution factors to ocular injuries are summarized

in Tables 6 and 7 using linear regression test.

The independent variable as a set accounts for 7%

of variance in ocular injuries. The overall regression

model was significant. F (1.5.11)=6.4, P value less

than 0.05, R square is 0.077. This is illustrated in Table

7.

Table 6: Model Summary.

The role of Pharmacological treatment for orbito-zygomatic

bone fracture

Ice packs and head elevation are recommended for

the Patient with orbital floor fracture for 48 hours

to reduce the swelling [10,11]. Moreover, Patient

should be informed not to blow the nose to prevent

the emphysema for 4 to 6 weeks after the injury.

Patient with limited ocular movements may benefit

from short term use of steroids (0.75-1 mg/kg per

day of prednisone) if not contraindicated. Steroids

treatment helps for peri orbital and extra ocular

muscle edema to subside quickly and helps to decide

whether this limited ocular movement is transient or

if surgery is needed. Nasal decongestant and antibiotics

are advised for one week.

Conclusion: Ocular injuries are a relatively common

complication of orbitozygomatic fractures occurring

in 23 of patients (14.7%) in this study. These injuries

are more frequently seen in patients with comminuted

orbito-zygomatic fractures 15 (44%) followed by

orbital blowout fractures 6 (42.9%). Although simple

zygomatic complex fractures has low incidence (n=2,

1.9%), it associated with major ocular complication

if brain injuries present. Ophthalmology consultation

and ocular examination of at least three components;

visual acuity, ocular movement, and pupil reaction to

light are strongly recommended for Group-2 and 3

presenting with orbito-zygomatic fractures.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi