Research Article

Development and Testing of a Curriculum for Teaching Informed Consent for Spinal Anesthesia to Anesthesiology Residents

Pedro Tanaka1*, Leeanne Park1, Maria Tanaka1, Ankeet D Udani2 and Alex Macario1

1Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, USA

2Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Pedro Tanaka

Department: Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, USA

Tel: 650-724-4066

Fax: 650-724-4066

E-mail: ptanaka@stanford.edu

Received date: August 2, 2016; Accepted date: August 17, 2016; Published date: August 22, 2016

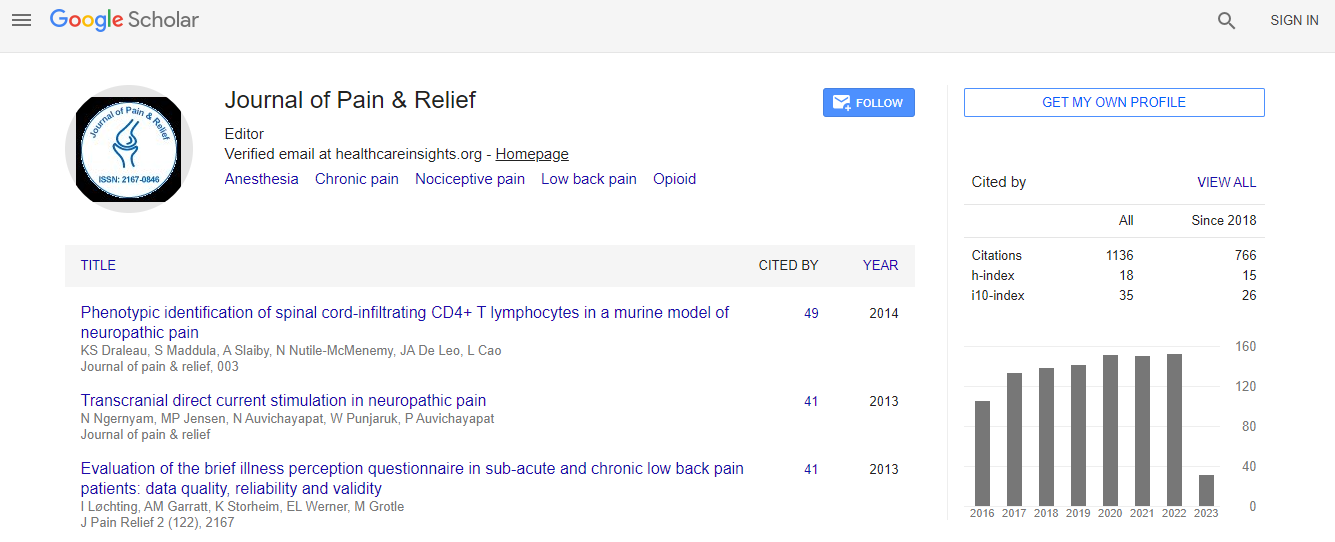

Citation: Tanaka P, Park L, Tanaka M, Udani DA, Macario A (2016) Development and Testing of a Curriculum for Teaching Informed Consent for Spinal Anesthesia to Anesthesiology Residents. J Pain Relief 5:259. doi:10.4172/2167-0846.1000259

Copyright: © 2016 Tanaka P, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: Properly obtaining informed consent for spinal anesthesia is a skill expected of anesthesiology residents. The goals of the study were to 1) use a Delphi method to develop a curriculum for teaching informed consent for spinal anesthesia, and a checklist of required elements; 2) determine which elements of the informed consent process were most frequently missed prior to the curriculum; 3) quantify if this curriculum improved performance of correctly obtaining informed consent from a standardized patient; and 4) measure retention of learning as measured by how residents performed on actual patients. Methods: Performance on obtaining informed consent was tested with an 11-item checklist on a standardized patient before and after completing the curriculum. Resident performance on their next three patients scheduled to have spinal anesthesia was evaluated at the bedside using the same checklist. Results: At baseline before completing the curriculum 18 anesthesia residents (39% female) with a mean 6.29 months (SD 3.59, median 6.5, 25th-75th quartile range 4.25-9.75) of residency completed and 11.39 prior spinals (SD 13.1, median 13.14, 25th-75th quartile range 3-14) successfully performed 47% (SD 20%, median 45%, 25th-75th quartile range 36-41%) of the 11 required elements. The 3 most commonly missed elements were: “Teach back: Ask the patient to repeat key items in discussion” (0% correct), “Connect, Introduce, Communicate, Ask permission, Respond, Exit” (6%), and “Have the patient verbally agree with the consent forms (17%).” 7 residents completed the written materials and video curriculum and significantly increased their performance to successfully complete 90% of the required elements on a standardized patient, and 86% on actual patients 1-5 days later (P<0.01). 11 other residents completed the written materials and video curriculum supplemented with a 1:1 session with a faculty and significantly increased the percentage of properly completed elements to 97% on the standardized patient, and to 88% on actual patients (P<0.01). Conclusions: The curriculum developed increased performance on how well informed consent was obtained by junior anesthesia residents on an 11 item checklist and may be used by training programs to teach and evaluate their residents.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi