Working Conditions and Health in MENA Region During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Keeping an Eye on The Gap.

Received: 01-Oct-2022 / Manuscript No. omha-22-76884 / Editor assigned: 04-Oct-2022 / PreQC No. omha-22-76884 / Reviewed: 18-Oct-2022 / QC No. omha-22-76884 / Revised: 22-Oct-2022 / Manuscript No. omha-22-76884 / Published Date: 28-Oct-2022 DOI: 10.4172/2329-6879.1000431

Abstract

Background: The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the workplace, both in terms of the number of cases among the working population and the massive modifications necessary to cope.

Objectives: The purpose of this study is to assess the influence of COVID-19 on wage earners' working conditions and health in the Middle East and South Africa (MENA) region.

Methods: Cross-sectional study was conducted between the mid of November and the end of December 2021 among the wage- earning population. Sample included n = 7555 participants obtained through an online survey.

Results: Work post attendance was clearly lower during the epidemic. 42.4%, 49.2% expressed concern about possible job loss, 53.2% expressed concern about finding a new job if they lost their current job, 56.7% expressed concern about salary reduction, 69.1% expressed concern about becoming infected at work, and 77.2% expressed concern about being a virus transmitter. A total of 33.5% of individuals who went to work on a regular basis did so with symptoms consistent with COVID-19, and 37.1% did so without proper protection measures. A total of 19.8% of workers felt their health had deteriorated, 64.9% reported having serious difficulty sleeping in the previous month, and 64.2% were at risk of poor mental health. The consumption of sleeping drugs, opioids, and painkillers increased significantly in comparison to the pre-pandemic period.

Conclusion: At the height of the pandemic, the findings presented here provide a very disturbing picture of the standard of working conditions and the health of employees living in the MENA region. When compared to available comparisons, we typically see unhealthy working circumstances and significant decline in health markers.

Keywords

COVID-19; Working conditions; Occupational health; Inequalities; MENA region; Psychology

Abbreviations

WHO-World Health Organization,

PHEIC-Public Health Emergency of International Concern

WFH-Work from Home

Introduction

On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the COVID-19 outbreak was a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) [1]. In the following weeks, the virus spread rapidly around the world, compelling governments in afflicted nations to enact lockdown measures aimed at reducing transmission rates and preventing hospital emergency rooms from becoming overcrowded [2]. Consequently, a large proportion of the working population was confronted immediately with major changes in daily life. People who commuted to work and maintained active social lives outside of their homes were forced to work from home (WFH), many employees were furloughed or laid off as various businesses and industries closed, and health care workers in emergency rooms, supermarket staff, and other essential employees faced a dramatic increase in workload and job strain [3, 4].

In terms of the COVID-19 crisis's public health impact, various studies indicate that working conditions have deteriorated and that employees are more likely to suffer from mental health disorders such as stress, depression, and anxiety [5, 6]. In particular, women, young adults, people with chronic diseases, and those who have lost their jobs as a result of the crisis seem to be the most affected [7, 8]. However, the crisis's implications and social responses to the virus's problems are not completely negative. Additionally, the new circumstance provides an opportunity for good changes in our professional and personal lives that were previously unthinkable prior to the COVID-19 catastrophe.

Regarding the literature related to this topic, certain participants reported feeling knowledgeable and well prepared for the changing work environment and WFH. Additionally, participants reported various benefits of working from home, including perceived control over the workday, increased efficiency, and the ability to save time formerly spent travelling. In comparison, some of the stated downsides of WFH were social isolation, diminished perceived value of labor, and a lack of critical work equipment. No certain participants reported familiarity with and readiness for their new work environment and WFH. Additionally, participants reported a range of benefits connected with telecommuting, including increased perceived control over the workday, increased efficiency, and the possibility of reclaiming time formerly spent travelling. No certain participants reported familiarity with and readiness for their new work environment and WFH. From there, this paper presents the main results of the survey “The effect of COVID-19 on working conditions, health, and practice of workers in the MENA region”. Their purpose was to raise awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic's influence on the working conditions and health of MENA region wage earners.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study population consists of all wage earners residing in the MENA region who had a job, including people who were subsequently fired, affected by a temporary lay-off procedure, or who completed their work under restricted conditions.

Design, Data Collection and Sample Size

Observational cross-sectional study. The data come from an online survey conducted between 1 November and 15 December 2021. Sample size calculation was conducted using Epi Info software. The population size was obtained from the World Bank, the confidence interval was set to 95%, and the expected frequency was set to 50%. To cover a variety of people from both the educated and the illiterate, we conducted the study through two methods: 1) an online survey using Google forms and then distributed it through different social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn. 2) on-ground data collection. Participants aged 18 years or higher were included in the study and had to give consent to use the data for research purposes without revealing identity. Eleven out of 15 countries achieved the targeted sample size. The rest were excluded for not reaching the calculated sample size. Another response was excluded for unreliable or incomplete data. The final sample consists of n = 7555 participants.

Variables

Our survey was mainly based on a Spanish survey that was conducted during the period 29 November and 28 December 2021 (between six and ten weeks after the state of alert was declared in Spain). In this survey, various questions were prepared ad hoc for this investigation; others were obtained from the third psychosocial risks survey carried out in Spain (ERP-2016), from the survey on alcohol and other drugs in Spain (EDADES) of the National Drug Plan [9], from the SF-36 [10] and items corresponding to the short version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (CoPsoQ) [11] adapted and validated in Spain (COPSOQ-Istas21). The variables in our version were recorded corresponding to different blocks: a) sociodemographic, b) mental health status and drug consumption, c) organizational measures and working conditions, and d) sick leave and sickness presentism. The survey questions used in this paper are shown in [Table 1]. The questionnaire was developed in English. Therefore, we translated into Arabic, where two bilinguals initially performed forward translation, and then another bilingual performed a backwards translation; the translated versions were compared and checked until a final draft was agreed on.

| Topic | Question | Responses | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| General health | How do you consider your current state of health, compared to what you had before the state of alert was declared? | Better/Not altered/Worse | Ad hoc |

| Sleep problems | During the lockdown, how often have you slept badly and restlessly? | A few times/Always/Many times/Never/Sometimes | COPSOQ3 |

| At risk of poor mental health | Q1: During the lockdown, weeks, how often have you been very nervous? | Always/Most of the time/A good bit of the time/Some of the time/A little of the time/Never | SF-36 |

| Q2: During the lockdown, how often have you felt calm and peaceful? | |||

| Q3: During the lockdown, how often have you been happy? | |||

| Q4: During the lockdown, how often have you felt sad or unhappy | |||

| Q5: During the past 4 weeks, how often have you felt so depressed that nothing could cheer you up? | |||

| Tranquilizers | During lockdown, had you used sedatives, sleeping pills? | No/Yes, I do not usually consume them but in this period I have/Yes, I was taking before and now I take the same dose/Yes, I was taking before but now I have increased the dose or I have changed to a stronger one | EDADES |

| Painkillers (opioids) |

During lockdown, had you used painkiller "opioids"? | ||

| Organizational measures and COVID sick leave | Since the state of alert was declared, in what situations have you been? and Today, what is your situation? | Combination of teleworking and going to work/Contract suspension/COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with negative test/COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with positive test/COVID-19 sick leave with negative test/COVID-19 sick leave with positive test/Fired/Mainly going to work to the workpost/Mainly teleworking/Not renewed/Suspension and reduction/Working time reduction | Ad hoc |

| Salary covering basic needs |

How often did your current salary cover the daily basic needs of your home? | Always/Many times/Never/Only once/Sometimes | ERP16 |

| Job loss insecurity | Did you worry about becoming unemployed? | To a very large extent/To a large extent/Somewhat/To a small extent/To a very small extent | COPSOQ3 |

| Labor market insecurity |

Did you worry about it being difficult for you to find another job if you became unemployed? | ||

| Wage insecurity | Did you worry about a decrease in your salary? | ||

| Worrying about COVID19 infection at work | Did you worry about the possibility of becoming infected with COVID-19 at work? | To a very large extent/To a large extent/Somewhat/To a small extent/To a very small extent | Ad hoc |

| Worrying about spreading COVID19 |

Did you worry about the possibility of infecting someone with COVID-19? | ||

| Working without protection against COVID19 | Since the state of alert was declared, did you have had to work without adequate protection measures to avoid contagion by COVID 19? | Always/Often/Sometimes/Seldom/Never | Ad hoc |

| Working with COVID-19 symptoms | Since the state of alert was declared, had you gone to work with symptoms (fever, cough, shortness of breath or general malaise)? | No, never/Yes, few days/Yes, some days/Yes, most days/Yes, always | Ad hoc |

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R Software version 3.5.2. Qualitative data were reported as frequencies and percentages, and quantitative data were reported as the means and standard deviations. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the predictors of the risk of poor mental health. The P value was considered significant if P <0.05.

Results

The survey was carried out on 7555 participants, 99.9% of whom were complete responders. The participants' sociodemographic characteristics are represented as counts (%) in [Table 2].

| Demographics (N = 7567) | Count (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18-35 years | 5436 (72.4) |

| 36-50 years | 1685 (22.4) | |

| More than 50 years | 391 (5.2) | |

| Gender | Female | 4478 (59.9) |

| Male | 2999 (40.1) | |

| Country | Algeria | 716 (9.5) |

| Egypt | 726 (9.6) | |

| Iraq | 715 (9.4) | |

| Jordan | 558 (7.4) | |

| Kuwait | 3 (0.0) | |

| Lebanon | 5 (0.1) | |

| Libya | 752 (9.9) | |

| Morocco | 1 (0.0) | |

| Palestine | 607 (8.0) | |

| Qatar | 3 (0.0) | |

| Saudi Arabia | 569 (7.5) | |

| Sudan | 749 (9.9) | |

| Syria | 646 (8.5) | |

| Tunisia | 715 (9.4) | |

| Yemen | 802 (10.6) | |

| Marital status | divorced | 228 (3.0) |

| married | 3396 (44.9) | |

| single | 3870 (51.1) | |

| widower | 73 (1.0) | |

| Educational level | college student | 3737 (49.4) |

| High school/Diploma | 1091 (14.4) | |

| Post graduate | 2521 (33.3) | |

| Presecondary | 218 (2.9) | |

| Location | Camps | 135 (1.8) |

| Rural | 1455 (19.2) | |

| Urban | 5977 (79.0) | |

| Migrant status | Citizen | 4192 (55.4) |

| Migrant | 249 (3.3) | |

| Resident | 3126 (41.3) | |

| Chronic disease history | I do not have | 6372 (84.2) |

| Diabetes | 352 (4.7) | |

| Anemia | 27 (0.4) | |

| Cardiovascular | 319 (4.2) | |

| Hypertension | 461 (6.1) | |

| Kidney disease | 97 (1.3) | |

| Liver disease | 45 (0. 6 ) | |

| Respiratory disease | 135 (1.8) | |

| Others | 229 (3.0) | |

| Work in the medical field. | No | 4136 (54.7) |

| Yes | 3424 (45.3) | |

| Current living situation. | I live alone | 594 (7.8) |

| I live in a shared household | 889 (11.7) | |

| I live with my family | 6084 (80.4) | |

| Persons need the care | 5 or more | 1278 (16.9) |

| Less than 5 | 4170 (55.1) | |

| Nobody | 2119 (28.0) | |

| Job condition | I work for my own account | 2080 (29.0) |

| Part -time employee, a short -term contract employee | 1687 (23.5) | |

| Permanent Employee | 3407 (47.5) | |

| The workplace before the pandemic | Fieldwork | 1627 (21.5) |

| House | 1714 (22.7) | |

| House/Fieldwork | 4 (0.1) | |

| Office | 4192 (55.4) | |

| Office/Fieldwork | 21 (0.3) | |

| Office/House | 3 (0.0) | |

| Office/House/Fieldwork | 6 (0.1) | |

| The workplace during the pandemic | Fieldwork | 1360 (18.0) |

| House | 2868 (37.9) | |

| House/Fieldwork | 5 (0.1) | |

| Office | 3310 (43.7) | |

| Office/Fieldwork | 4 (0.1) | |

| Office/House | 11 (0.1) | |

| Office/House/Fieldwork | 9 (0.1) | |

| The economic situation. | Above average income | 1100 (14.5) |

| Above low income | 1143 (15.1) | |

| Average income | 3793 (50.1) | |

| High income | 288 (3.8) | |

| Low income | 1243 (16.4) |

Regarding Mental Health Status and Drug Consumption during the Pandemic

Table 3 showed that only 19.8% of the study participants reported that their health status had worsened during the pandemic, and 46.4% of them were not altered. Approximately 7.7%, 23.5% & 33.7% were always, many times & sometimes had slept badly and restlessly. Additionally, 64.2% of participants were at risk of poor mental health during the pandemic. Approximately 7.5% did not usually consume sedatives and sleeping pills, but in that period, they had, 3.7% were taking before and kept the same dose during the pandemic, and only 2.4% increased the dose or changed to a stronger dose. Additionally, 4.7% did not usually consume opioids, but in that period, they had, 3.4% were taking opioids before and kept the same dose during the pandemic, and only 1.7% of participants increased the dose of the painkiller or changed to a stronger one.

| Mental health & drug consumption | Count (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| How do you consider your current state of health, compared to what you had before the state of alert was declared? | Better | 1059 (33.8) |

| Not altered | 1456 (46.4) | |

| Worse | 620 (19.8) | |

| During the lockdown, how often have you slept badly and restlessly? | A few times | 1596 (21.1) |

| Always | 579 (7.7) | |

| Many times, | 1780 (23.5) | |

| Never | 1064 (14.1) | |

| Sometimes | 2548 (33.7) | |

| During the lockdown, weeks, how often have you been very nervous? | A good bit of the time | 841 (11.1) |

| A little of the time | 1424 (18.8) | |

| Always | 557 (7.4) | |

| Most of the time | 1633 (21.6) | |

| Never | 882 (11.7) | |

| Some of the time | 2230 (29.5) | |

| During the lockdown, how often have you felt calm and peaceful? | A good bit of the time | 1283 (17.0) |

| A little of the time | 1657 (21.9) | |

| Always | 549 (7.3) | |

| Most of the time | 1435 (19.0) | |

| Never | 352 (4.7) | |

| Some of the time | 2291 (30.3) | |

| During the lockdown, how often have you been happy? | A good bit of the time | 1368 (18.1) |

| A little of the time | 1766 (23.3) | |

| Always | 359 (4.7) | |

| Most of the time | 1147 (15.2) | |

| Never | 666 (8.8) | |

| Some of the time | 2261 (29.9) | |

| During the lockdown, how often have you felt sad or unhappy | A good bit of the time | 1020 (13.5) |

| A little of the time | 1688 (22.3) | |

| Always | 535 (7.1) | |

| Most of the time | 1607 (21.2) | |

| Never | 476 (6.3) | |

| Some of the time | 2241 (29.6) | |

| During the past 4 weeks, how often have you felt so depressed that nothing could cheer you up? | A good bit of the time | 862 (11.4) |

| A little of the time | 1740 (23.0) | |

| Always | 619 (8.2) | |

| Most of the time | 1367 (18.1) | |

| Never | 1232 (16.3) | |

| Some of the time | 1747 (23.1) | |

| Risk of poor mental health | At risk | 4856 (64.2) |

| Not at risk | 2711 (35.8) | |

| During lockdown, had you used sedatives, sleeping pills? | No | 6539 (86.4) |

| Yes, I do not usually consume them but in this period I have | 565 (7.5) | |

| Yes, I was taking before and now I take the same dose | 278 (3.7) | |

| Yes, I was taking before but now I have increased the dose or I have changed to a stronger one | 185 (2.4) | |

| During lockdown, had you used painkiller "opioids"? | No | 6825 (90.2) |

| Yes, I do not usually consume them but in this period I have | 355 (4.7) | |

| Yes, I was taking before and now I take the same dose | 260 (3.4) | |

| Yes, I was taking before but now I have increased the dose or I have changed to a stronger one | 127 (1.7) |

Regarding Organizational Measures, Working Conditions and COVID-19 Sick Leave during the Pandemic

Table 4 showed that 42.8% of participants mainly went to work to the work post during the pandemic, while 21.6% mainly worked remotely by teleworking, 15% had combined teleworking and going to work, 24.9% had reduced their working time, 4.9% had a contract suspension, 2.9% had suspension & reduction, 3.9% had been fired and 6.5% had not renewed their contract. 13.0%, 15.5 and 38.9% had always, many times and sometimes sufficient salary covering their basic needs, respectively. A total of 15.2%, 15.5% and 18.5% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, job loss insecurity, respectively. While 15.3%, 17.5% and 20.4% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, labor market insecurity, respectively. Additionally, 16.0%, 19.1% and 21.6% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, wage insecurity, respectively. Meanwhile, 10.0%, 24.3% and 34.8% were somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent worrying about the possibility of becoming infected with COVID-19 at work, respectively. Approximately 7.5%, 24.5% and 45.2% were somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent worrying about spreading COVID-19, respectively.

| Organizational & working conditions | Count (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Since the state of alert was declared, in what situations have you been? and Today, what is your situation? | Combination of teleworking and going to work | 1137 (15) |

| Contract suspension | 369 (4.9) | |

| COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with negative test | 85 (1.1) | |

| COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with positive test | 294 (3.9) | |

| COVID-19 sick leave with negative test | 202 (2.7) | |

| COVID-19 sick leave with positive test | 864 (11.4) | |

| Fired | 298 (3.9) | |

| Mainly going to work to the work post | 3240 (42.8) | |

| Mainly teleworking | 1638 (21.6) | |

| Not renewed | 491 (6.5) | |

| Suspension and reduction | 216 (2.9) | |

| Working time reduction | 1881 (24.9) | |

| How often did your current salary cover the daily basic needs of your home? | Always | 981 (13.0) |

| Many times | 1175 (15.5) | |

| Never | 1973 (26.1) | |

| Only once | 497 (6.6) | |

| Sometimes | 2940 (38.9) | |

| Did you worry about becoming unemployed? | Somewhat | 1153 (15.2) |

| To a large extent | 1173 (15.5) | |

| To a small extent | 1742 (23.0) | |

| To a very large extent | 1397 (18.5) | |

| To a very small extent | 2101 (27.8) | |

| Did you worry about it being difficult for you to find another job if you became unemployed? | Somewhat | 1160 (15.3) |

| To a large extent | 1327 (17.5) | |

| To a small extent | 1667 (22.0) | |

| To a very large extent | 1546 (20.4) | |

| To a very small extent | 1862 (24.6) | |

| Did you worry about a decrease in your salary? | Somewhat | 1212 (16.0) |

| To a large extent | 1444 (19.1) | |

| To a small extent | 1706 (22.5) | |

| To a very large extent | 1637 (21.6) | |

| To a very small extent | 1567 (20.7) | |

| Did you worry about the possibility of becoming infected with COVID-19 at work? | Somewhat | 760 (10.0) |

| To a large extent | 1840 (24.3) | |

| To a small extent | 1734 (22.9) | |

| To a very large extent | 2633 (34.8) | |

| To a very small extent | 600 (7.9) | |

| Did you worry about the possibility of infecting someone with COVID-19? | Somewhat | 566 (7.5) |

| To a large extent | 1854 (24.5) | |

| To a small extent | 1337 (17.7) | |

| To a very large extent | 3417 (45.2) | |

| To a very small extent | 393 (5.2) | |

| Since the state of alert was declared, did you have had to work without adequate protection measures to avoid contagion by COVID 19? | Always | 429 (13.2) |

| Never | 1149 (35.5) | |

| Often | 623 (19.2) | |

| Seldom | 1002 (30.9) | |

| Sometimes | 37 (1.1) | |

| Since the state of alert was declared, had you gone to work with symptoms (fever, cough, shortness of breath or general malaise)? | No, never | 1140 (35.2) |

| Yes, always | 105 (3.2) | |

| Yes, few days | 896 (27.7) | |

| Yes, most days | 278 (8.6) | |

| Yes, some days | 821 (25.3) |

Regarding COVID-19 sick leave, approximately 1.1% of participants had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a negative test, 3.9% had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a positive test, 2.7% had COVID-19 sick leave with a negative test and 11.4% had COVID-19 sick leave with a positive test. Among those who were mainly going to their work to the work post, approximately 13.2%, 19.2% & 1.1% were always, often & sometimes had to work without adequate protection measures to avoid contagion by COVID-19, respectively, and approximately 3.2%, 8.6% & 25.3% had always, most days, & some days gone to work with symptoms (fever, cough, shortness of breath or general malaise), respectively.

Regarding Health-Related Inequalities and Working Conditions by Salary and by Working in the Medical Field

Table 5 showed that among those participants who had a sufficient salary covering their basic needs, 37.2% and 20.4% had better changes and worse changes in general health, respectively, during the pandemic than during the pandemic, while approximately 5.9%, 21.3%, and 31.9% had always, many times and sometimes sleep problems, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, 49.6% of them were at risk of poor mental health. A total of 5.1%, 4.1% and 2.7% of them were new consumers for tranquilizers and consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, 3.1%, 3.8% and 2.4% of them were new consumers for opioids, consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively, during the pandemic. Among those who were included in the medical field, 32.9% and 21.9% had better changes and worse changes in general health, respectively, during the pandemic than before the pandemic, and approximately 7.4%, 23.7 and 33.2% had always, many times and sometimes sleep problems, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, 63.1% of them were at risk of poor mental health. A total of 6.7%, 3.9% and 2.2% of them were new consumers for tranquilizers and consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, 4.4%, 3.5% and 1.5% of them were new consumers for opioids, consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively, during the pandemic.

| Health & drugs consumption | Salary covering basic needs | P value | Working in medical field | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient N = 5410 |

Sufficient N = 2156 |

No N = 4136 |

Yes N = 3424 |

||||

| Better changes in general health | 694 (32.2) | 365 (37.2) | 0.005 | 542 (34.7) | 517 (32.9) | 0.01 | |

| Worse changes in general health | 420 (19.5) | 200 (20.4) | 275 (17.6) | 345 (21.9) | |||

| Sleep problems | Always | 452 (8.4) | 127 (5.9) | <0.001 | 327 (7.9) | 252 (7.4) | 0.632 |

| Many times | 1320 (24.4) | 459 (21.3) | 969 (23.4) | 810 (23.7) | |||

| Sometimes | 1861 (34.4) | 687 (31.9) | 1410 (34.1) | 1136 (33.2) | |||

| At risk of poor mental health | 3785 (70.0) | 1070 (49.6) | <0.001 | 2688 (65.0) | 2162 (63.1) | 0.1 | |

| Tranquilizers | New consumer | 453 (8.4) | 111 (5.1) | <0.001 | 334 (8.1) | 231 (6.7) | 0.095 |

| The same dose | 190 (3.5) | 88 (4.1) | 146 (3.5) | 132 (3.9) | |||

| Increased dose | 127 (2.3) | 58 (2.7) | 108 (2.6) | 77 (2.2) | |||

| Painkillers (opioids) | New consumer | 289 (5.3) | 66 (3.1) | <0.001 | 203 (4.9) | 152 (4.4) | 0.556 |

| The same dose | 178 (3.3) | 82 (3.8) | 139 (3.4) | 121 (3.5) | |||

| Increased dose | 76 (1.4) | 51 (2.4) | 75 (1.8) | 52 (1.5) | |||

Table 6 showed that among those participants who had a sufficient salary covering their basic needs, 48.8% mainly went to their work to the work post, 22.5% changed to mainly teleworking, 18.2% had combined teleworking and going to work, 22.1% had reduced their working time, 2.7% had their contracts suspended, 1.3% had suspension & reduction, 1.9% had been fired and 3.4% had not renewed their contract. Additionally, 10.7%, 12.9% and 10.7% of them had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent, job loss insecurity, respectively, during the pandemic. In addition, 11.2%, 13.8% and 13.7% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, labor market insecurity, respectively. Additionally, 15.5%, 15.0% and 12.2% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, wage insecurity, respectively. Additionally, approximately 9.7%, 26.6% and 32.1% were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worrying about COVID-19 infection at work, respectively. 6.6%, 26.2% and 45.2% were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worrying about spreading COVID-19, respectively. Among those who were going to work to the work post and had a sufficient salary covering their basic needs, approximately 11.2%, 16.3% and 2.1% had always, often and sometimes gone to their work without protection against COVID-19, respectively, and approximately 1.8%, 4.5% and 24.6% had always, most days and some days gone to their work with COVID-19 symptoms, respectively. Regarding COVID-19 sick leave among those who had a sufficient salary covering their basic needs, 1.3% of them had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a negative test, 5.6% had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a positive test, 3.7% had COVID-19 sick leave with a negative test and 17.9% had COVID-19 sick leave with a positive test.

| Organizational & working conditions | Salary covering basic needs | Working in medical field | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient n= 5410 | Sufficient n= 2156 |

No N = 4136 |

Yes N = 3424 |

||

| Combination of teleworking and going to work | 745 (13.8) | 392 (18.2) | 709 (17.1) | 428 (12.5) | |

| Contract suspension | 310 (5.7) | 59 (2.7) | 237 (5.7) | 132 (3.9) | |

| COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with negative test | 57 (1.1) | 28 (1.3) | 44 (1.1) | 37 (1.1) | |

| COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with positive test | 174 (3.2) | 120 (5.6) | 145 (3.5) | 149 (4.4) | |

| COVID-19 sick leave with negative test | 123 (2.3) | 79 (3.7) | 127 (3.1) | 75 (2.2) | |

| COVID-19 sick leave with positive test | 479 (8.9) | 385 (17.9) | 421 (10.2) | 443 (12.9) | |

| Fired | 256 (4.7) | 42 (1.9) | 212 (5.1) | 86 (2.5) | |

| Mainly going to work to the work post | 2187 (40.4) | 1053 (48.8) | 1485 (35.9) | 1751 (51.1) | |

| Mainly teleworking | 1153 (21.3) | 485 (22.5) | 1069 (25.8) | 569 (16.6) | |

| Not renewed | 417 (7.7) | 74 (3.4) | 318 (7.7) | 170 (5.0) | |

| Suspension and reduction | 189 (3.5) | 27 (1.3) | 159 (3.8) | 57 (1.7) | |

| Working time reduction | 1404 (26.0) | 477 (22.1) | 1170 (28.3) | 711 (20.8) | |

| Job loss insecurity | Somewhat | 923 (17.1) | 230 (10.7) | 585 (14.1) | 567 (16.6) |

| To a large extent | 894 (16.5) | 279 (12.9) | 709 (17.1) | 464 (13.6) | |

| To a very large extent | 1166 (21.6) | 231 (10.7) | 918 (22.2) | 475 (13.9) | |

| Labor market Insecurity |

Somewhat | 919 (17.0) | 241 (11.2) | 603 (14.6) | 556 (16.2) |

| To a large extent | 1029 (19.0) | 298 (13.8) | 771 (18.7) | 554 (16.2) | |

| To a very large extent | 1252 (23.1) | 294 (13.7) | 994 (24.1) | 548 (16.0) | |

| Wage insecurity | Somewhat | 878 (16.2) | 334 (15.5) | 637 (15.4) | 574 (16.8) |

| To a large extent | 1120 (20.7) | 324 (15.0) | 871 (21.1) | 571 (16.7) | |

| To a very large extent | 1374 (25.4) | 263 (12.2) | 1027 (24.8) | 606 (17.7) | |

| Worrying about COVID19 infection at work | Somewhat | 551 (10.2) | 209 (9.7) | 432 (10.4) | 328 (9.6) |

| To a large extent | 1266 (23.4) | 574 (26.6) | 985 (23.8) | 852 (24.9) | |

| To a very large extent | 1941 (35.9) | 691 (32.1) | 1309 (31.6) | 1324 (38.7) | |

| Worrying about spreading COVID19 |

Somewhat | 424 (7.8) | 142 (6.6) | 360 (8.7) | 206 (6.0) |

| To a large extent | 1289 (23.8) | 565 (26.2) | 967 (23.4) | 881 (25.7) | |

| To a very large extent | 2441 (45.1) | 975 (45.2) | 1651 (39.9) | 1765 (51.5) | |

| Working without protection against COVID19 | Always | 311 (14.2) | 118 (11.2) | 235 (15.8) | 194 (11.1) |

| Often | 451 (20.6) | 172 (16.3) | 309 (20.8) | 310 (17.7) | |

| Sometimes | 15 (0.7) | 22 (2.1) | 5 (0.3) | 32 (1.8) | |

| Working with COVID-19 symptoms | Yes, always | 86 (3.9) | 19 (1.8) | 31 (2.1) | 74 (4.2) |

| Yes, most days | 231 (10.6) | 47 (4.5) | 137 (9.2) | 141 (8.1) | |

| Yes, some days | 562 (25.7) | 259 (24.6) | 369 (24.8) | 448 (25.6) | |

Among those who were included in the medical field, 51.1% mainly went to their work to the work post, 16.6% changed to mainly teleworking, 12.5% had combined teleworking and going to work, 20.8% had reduced their working time, 3.9% had their contracts suspended, 1.7% had suspension & reduction, 2.5% had been fired and 5.0% had not renewed their contract. Additionally, 16.6%, 13.6% and 13.9% of them had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent, job loss insecurity, respectively, during the pandemic. In addition, 16.2%, 16.2% and 16.0% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, labor market insecurity, respectively. Additionally, 16.8%, 16.7% and 17.7% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, wage insecurity, respectively. Additionally, approximately 9.6%, 24.9% and 38.7% were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worrying about COVID-19 infection at work, respectively. 6.0%, 25.7% and 51.5% were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worrying about spreading COVID-19, respectively. Among those who were going to work to the work post and were included in the medical field, approximately 11.1%, 17.7% and 1.8% had always, often and sometimes gone to their work without protection against COVID-19, respectively, and approximately 4.2%, 8.1% and 25.6% had always, most days and some days gone to their work with COVID-19 symptoms, respectively. Regarding COVID-19 sick leave among those who were included in the medical field, 1.1% of them had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a negative test, 4.4% had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a positive test, 2.2% had COVID-19 sick leave with a negative test and 12.9% had COVID-19 sick leave with a positive test.

Regarding Health-Related Inequalities and Working Conditions by Age & Gender

Table 7 showed that approximately 34.0% of participants aged 18-35 years, 33.6% of participants aged 36-50 years and 32.5% of participants over 50 years had better changes in general health during the pandemic compared to the prepandemic period, while approximately 18.4% of participants aged 18-35 years, 23.6% of participants aged 36-50 years and 21.9% of participants over 50 years had worse changes in general health during the pandemic compared to the prepandemic period. Additionally, among participants in the 18-35 years age group, 8.5%, 23.9% and 33.6% had always, many times and sometimes sleep problems, respectively; for those aged 36-50 years, 6.2%, 21.4% and 34.7% had always, many times and sometimes sleep problems, respectively; and 3.1%, 25.1% and 32.5% of those over 50 years had always, many times and sometimes sleep problems, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, approximately 65.8% of those aged 18-35 years, 61.6% of those aged 36-50 years and 53.2% of those over 50 years were at risk of poor mental health during the pandemic. Approximately 7.2%, 3.6% and 2.4% of those aged 18-35 years were new consumers of tranquilizers who consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, 8.4%, 3.5% and 1.8% of those aged 36-50 years were new consumers for tranquilizers, who consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively. In addition, 6.6%, 5.6% and 5.1% of those over 50 years were new consumers for tranquilizers, who consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively. Regarding opioid consumption, 4.3%, 3.3% and 1.5% of those aged 18-35 years were new consumers for opioids, consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, approximately 5.7%, 3.1% and 1.8% of those aged 36-50 years were new consumers who consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively. Approximately 5.6%, 6.4% and 2.6% of those over 50 years were new consumers who consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively.

| Health & drugs consumption | Age | P value | Gender | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-35 years N =5436 |

36-50 years N =1685 |

More than 50 years N =391 |

Female N = 4478 |

Male N =2999 |

||||

| Better changes in general health | 742 (34.0) | 257 (33.6) | 55 (32.5) | 0.03 | 661 (35.0) | 379 (31.3) | <0.001 | |

| Worse changes in general health | 402 (18.4) | 180 (23.6) | 37 (21.9) | 406 (21.5) | 211 (17.4) | |||

| Sleep problems | Always | 462 (8.5) | 105 (6.2) | 12 (3.1) | <0.001 | 375 (8.4) | 193 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Many times | 1299 (23.9) | 361 (21.4) | 98 (25.1) | 1183 (26.4) | 575 (19.2) | |||

| Sometimes | 1827 (33.6) | 584 (34.7) | 127 (32.5) | 1472 (32.9) | 1046 (34.9) | |||

| At risk of poor mental health | 3577 (65.8) | 1038 (61.6) | 208 (53.2) | <0.001 | 2996 (66.9) | 1799 (60.0) | <0.001 | |

| Tranquilizers | New consumer | 391 (7.2) | 142 (8.4) | 26 (6.6) | 0.001 | 356 (7.9) | 200 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| The same dose | 196 (3.6) | 59 (3.5) | 22 (5.6) | 132 (2.9) | 136 (4.5) | |||

| Increased dose | 130 (2.4) | 30 (1.8) | 20 (5.1) | 89 (2.0) | 89 (3.0) | |||

| Painkillers (opioids) | New consumer | 232 (4.3) | 96 (5.7) | 22 (5.6) | 0.001 | 206 (4.6) | 137 (4.6) | 0.645 |

| The same dose | 177 (3.3) | 53 (3.1) | 25 (6.4) | 149 (3.3) | 110 (3.7) | |||

| Increased dose | 81 (1.5) | 31 (1.8) | 10 (2.6) | 70 (1.6) | 56 (1.9) | |||

Additionally, 31.3% of males and 35.0% of females had better changes in general health during the pandemic than before the pandemic, while approximately 17.4% of males and 21.5% of females had worse changes in general health during the pandemic than before the pandemic. Additionally, 6.4%, 19.2% and 34.9% of males had always; many times and sometimes sleep problems, respectively, during the pandemic, while approximately 8.4%, 26.4% and 32.9% of females had always, many times and sometimes sleep problems, respectively. Additionally, approximately 60.0% of males and 66.9% of females were at risk of poor mental health during the pandemic. Additionally, 6.7%, 4.5% and 3.0% of males were new consumers for tranquilizers, consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively, during the pandemic, while 7.9%, 2.9% and 2.0% of females were new consumers for tranquilizers, consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively. Additionally, regarding opioid consumption, 4.6%, 3.7% and 1.9% of males were new consumers for opioids, consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively, during the pandemic, while 4.6%, 3.3% and 1.6% of females were new consumers, consumed the same dose and increased the dose, respectively.

Table 8 showed that among those aged 18-35 years, 39.5% were mainly going to their work to the work post, 21.7% changed to mainly teleworking, 13.1% had combined teleworking and going to work, 23.1% had reduced their working time, 5.7% had their contracts suspended, 3.3% had suspension and reduction, 4.8% had been fired and 7.5% had not renewed their contract. Additionally, 15.4%, 16.9% and 21.6% of them had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent, job loss insecurity, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, 15.1%, 18.8% and 22.9% of them had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent labor market insecurity, respectively. In addition, 16.2%, 19.8% and 23.0% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, wage insecurity, respectively. Additionally, 9.7%, 24.3% and 35.2% of them were somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent worrying about COVID-19 infection at work, respectively. In addition, 6.6%, 24.2% and 47.0% were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worrying about spreading COVID-19, respectively. Additionally, among those who were going to their work to the work post in this age group, approximately 12.2%, 20.0% and 1.2% had always, often and sometimes gone to their work without protection against COVID-19, respectively, and approximately 3.7%, 9.6% and 25.8% of them had always, most days and some days gone to their work with COVID-19 symptoms, respectively. Regarding COVID-19 sick leave among this age group, approximately 1.3% had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a negative test, 3.7% had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a positive test, 2.5% had COVID-19 sick leave with a negative test and 9.3% had COVID-19 sick leave with a positive test.

| Organizational & working conditions | Age | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-35 years N =5436 |

36-50 years N =1685 |

More than 50 years N =391 |

Female N = 4478 |

Male N =2999 |

|||

| Combination of teleworking and going to work | 714 (13.1) | 345 (20.5) | 74 (18.9) | 667 (14.9) | 451 (15.0) | ||

| Contract suspension | 308 (5.7) | 46 (2.7) | 14 (3.6) | 201 (4.5) | 161 (5.4) | ||

| COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with negative test | 73 (1.3) | 10 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 61 (1.4) | 24 (0.8) | ||

| COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with positive test | 200 (3.7) | 70 (4.2) | 24 (6.1) | 166 (3.7) | 123 (4.1) | ||

| COVID-19 sick leave with negative test | 133 (2.5) | 53 (3.1) | 14 (3.6) | 137 (3.1) | 63 (2.1) | ||

| COVID-19 sick leave with positive test | 505 (9.3) | 281 (16.7) | 71 (18.2) | 526 (11.8) | 321 (10.7) | ||

| Fired | 261 (4.8) | 15 (0.9) | 10 (2.6) | 151 (3.4) | 146 (4.9) | ||

| Mainly going to work to the work post | 2146 (39.5) | 908 (53.9) | 176 (45.0) | 1822 (40.7) | 1368 (45.6) | ||

| Mainly teleworking | 1177 (21.7) | 362 (21.5) | 84 (21.5) | 1132 (25.3) | 482 (16.1) | ||

| Not renewed | 408 (7.5) | 58 (3.4) | 23 (5.9) | 274 (6.1) | 208 (6.9) | ||

| Suspension and reduction | 177 (3.3) | 25 (1.5) | 14 (3.6) | 107 (2.4) | 103 (3.4) | ||

| Working time reduction | 1256 (23.1) | 480 (28.5) | 129 (33.0) | 979 (21.9) | 862 (28.7) | ||

| Job loss insecurity | Somewhat | 836 (15.4) | 258 (15.3) | 54 (13.8) | 690 (15.4) | 455 (15.2) | |

| To a large extent | 918 (16.9) | 193 (11.5) | 58 (14.8) | 633 (14.1) | 527 (17.6) | ||

| To a very large extent | 1174 (21.6) | 172 (10.2) | 39 (10.0) | 783 (17.5) | 582 (19.4) | ||

| Labor market Insecurity |

Somewhat | 822 (15.1) | 281 (16.7) | 51 (13.0) | 690 (15.4) | 456 (15.2) | |

| To a large extent | 1022 (18.8) | 228 (13.5) | 67 (17.1) | 725 (16.2) | 578 (19.3) | ||

| To a very large extent | 1245 (22.9) | 244 (14.5) | 51 (13.0) | 874 (19.5) | 647 (21.6) | ||

| Wage insecurity | Somewhat | 881 (16.2) | 273 (16.2) | 49 (12.5) | 770 (17.2) | 427 (14.2) | |

| To a large extent | 1076 (19.8) | 269 (16.0) | 86 (22.0) | 801 (17.9) | 623 (20.8) | ||

| To a very large extent | 1252 (23.0) | 309 (18.3) | 66 (16.9) | 901 (20.1) | 706 (23.5) | ||

| Worrying about COVID19 infection at work | Somewhat | 526 (9.7) | 182 (10.8) | 40 (10.2) | 411 (9.2) | 335 (11.2) | |

| To a large extent | 1320 (24.3) | 415 (24.6) | 98 (25.1) | 1071 (23.9) | 755 (25.2) | ||

| To a very large extent | 1916 (35.2) | 580 (34.4) | 127 (32.5) | 1763 (39.4) | 834 (27.8) | ||

| Worrying about spreading COVID19 |

Somewhat | 357 (6.6) | 165 (9.8) | 33 (8.4) | 308 (6.9) | 245 (8.2) | |

| To a large extent | 1318 (24.2) | 397 (23.6) | 121 (30.9) | 1130 (25.2) | 706 (23.5) | ||

| To a very large extent | 2556 (47.0) | 706 (41.9) | 137 (35.0) | 2202 (49.2) | 1182 (39.4) | ||

| Working without protection against COVID19 | Always | 262 (12.2) | 138 (15.2) | 26 (14.8) | 222 (12.2) | 205 (15.0) | |

| Often | 429 (20.0) | 160 (17.6) | 33 (18.8) | 321 (17.6) | 286 (20.9) | ||

| Sometimes | 25 (1.2) | 11 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) | 22 (1.2) | 15 (1.1) | ||

| Working with COVID-19 symptoms | Yes, always | 80 (3.7) | 24 (2.6) | 1 (0.6) | 82 (4.5) | 23 (1.7) | |

| Yes, most days | 206 (9.6) | 61 (6.7) | 9 (5.1) | 156 (8.6) | 120 (8.8) | ||

| Yes, some days | 554 (25.8) | 212 (23.3) | 51 (29.0) | 450 (24.7) | 361 (26.4) | ||

Among the age group from 36-50 years, 53.9% were mainly going to their work to the work post, 21.5% changed to mainly teleworking, 20.5% had combined teleworking and going to work, 28.5% had reduced their working time, 2.7% had their contracts suspended, 1.5% had suspension and reduction, 0.9% had been fired and 3.4% had not renewed their contract. Additionally, 15.3%, 11.5% and 10.2% of them had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent, job loss insecurity, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, 16.7%, 13.5% and 14.5% of them had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent, labor market insecurity, respectively. In addition, 16.2%, 16.0% and 18.3% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, wage insecurity, respectively. Additionally, 10.8%, 24.6% and 34.4% of them were somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent worrying about COVID-19 infection at work, respectively. In addition, 9.8%, 23.6% and 41.9% were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worrying about spreading COVID-19, respectively. Additionally, among those who were going to their work to the work post in this age group, approximately 15.2%, 17.6% and 1.2% had always, often and sometimes gone to their work without protection against COVID-19, respectively, and approximately 2.6%, 6.7% and 23.3% of them had always, most days and some days gone to their work with COVID-19 symptoms, respectively. Regarding COVID-19 sick leave among this age group, approximately 0.6% had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a negative test, 4.2% had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a positive test, 3.1% had COVID-19 sick leave with a negative test and 16.7% had COVID-19 sick leave with a positive test.

Among those over 50 years, 45.0% were mainly going to their work to the work post, 21.5% changed to mainly teleworking, 18.9% had combined teleworking and going to work, 33.0% had reduced their working time, 3.6% had their contracts suspended, 3.6% had suspension and reduction, 2.6% had been fired and 5.9% had not renewed their contract. Additionally, 13.8%, 14.8% and 10.0% of them had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent, job loss insecurity, respectively, during the pandemic. Additionally, 13.0%, 17.1% and 13.0% of them had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent, labor market insecurity, respectively. In addition, 12.5%, 22.0% and 16.9% had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, wage insecurity, respectively. Additionally, 10.2%, 25.1% and 32.5% of them were somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent worrying about COVID-19 infection at work, respectively. In addition, 8.4%, 30.9% and 35.0% were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worrying about spreading COVID-19, respectively. Additionally, among those who were going to their work to the work post in this age group, approximately 14.8%, 18.8% and 0.6% had always, often and sometimes gone to their work without protection against COVID-19, respectively, and approximately 0.6%, 5.1% and 29.0% of them had always, most days and some days gone to their work with COVID-19 symptoms, respectively. Regarding COVID-19 sick leave among this age group, approximately 0.5% had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a negative test, 6.1% had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a positive test, 3.6% had COVID-19 sick leave with a negative test and 18.2% had COVID-19 sick leave with a positive test.

Additionally, approximately 45.6% of males and 40.7% of females were mainly going to their work to the work post, 16.1% of males and 25.3% of females changed to mainly teleworking, 15.0% of males and 14.9% of females had combined teleworking and going to work, 28.7% of males and 21.9% of females had reduced their working time, 5.4% of males and 4.5% of females had their contracts suspended, 3.4% of males and 2.4% of females had suspension and reduction, and 4.9% of males and 3.4% of females had been fired and 6.9% of males and 6.1% of females had not renewed their contract. Approximately 15.2%, 17.6%, and 19.4% of males had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent, job loss insecurity, respectively, during the pandemic, while 15.4%, 14.1% and 17.5% of females had somewhat, to a large extent & to a very large extent, job loss insecurity, respectively. Additionally, approximately 15.2%, 19.3% and 21.6% of males had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, labor market insecurity, respectively, while 15.4%, 16.2% and 19.5% of females had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, labor market insecurity, respectively. Additionally, approximately 14.2%, 20.8% and 23.5% of males had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, wage insecurity, respectively, while 17.2%, 17.9% and 20.1% of females had somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent, wage insecurity, respectively. A total of 11.2%, 25.2% and 27.8% of males were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worried about COVID-19 infection at work, respectively, while 9.2%, 23.9% and 39.4% of females were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worried about COVID-19 infection at work, respectively. In addition, 8.2%, 23.5% and 39.4% of males were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worried about spreading COVID-19, respectively, while 6.9%, 25.2% and 49.2% of females were somewhat, to a large extent and to a very large extent worried about spreading COVID-19, respectively. Additionally, among males who were going to their work to the work post, 15.0%, 20.9% and 1.1% of them had always, often and sometimes gone to their work without protection against COVID-19, respectively, and approximately 1.7%, 8.8% and 26.4% of them had always, most days and some days gone to their work with COVID-19 symptoms, respectively. Among females who were going to their work to the work post, 12.2%, 17.6% and 1.2% of them had always, often and sometimes gone to their work without protection against COVID-19, respectively, and approximately 4.5%, 8.6% and 24.7% of them had always, most days and some days gone to their work with COVID-19 symptoms, respectively. Regarding COVID-19 sick leave, approximately 0.8% of males and 1.4% of females had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a negative test, 4.1% of males and 3.7% of females had COVID-19 sick leave for contact with a person with a positive test, 2.1% of males and 3.1% of females had COVID-19 sick leave with a negative test, and 10.7% of males and 11.8% of females had COVID-19 sick leave with a positive test.

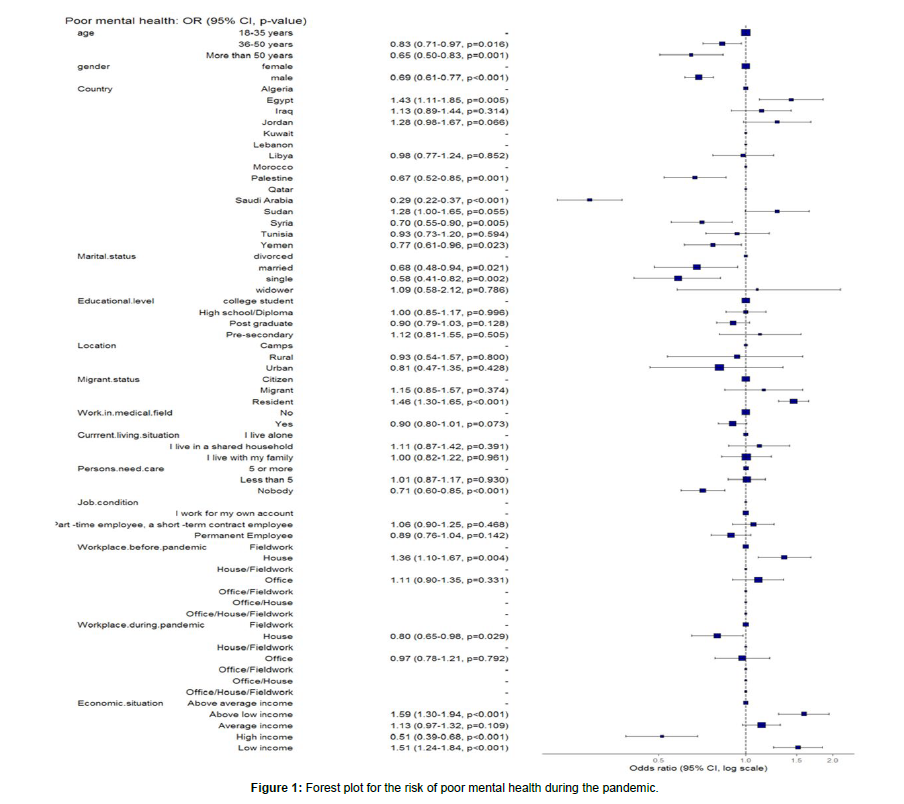

Sociodemographic predictors for poor mental health during the pandemic

The logistic regression models in [Table 9 & Figure 1] showed that the unadjusted odds of poor mental health decreased significantly among participants aged 36-50 years and participants over 50 years by approximately 17% and 41%, respectively, while after adjustment, they decreased significantly by approximately 17% and 35%, respectively, compared to younger participants aged 18-35 years. Crude (OR=0.83, 95% CI: (0.74-0.93), p=0.002), (OR=0.59, 95% CI: (0.48-0.73), p<0.001) & adjusted (OR=0.83, 95% CI: (0.71-0.97), p=0.016), (OR=0.65, 95% CI: (0.50-0.83), p=0.001), respectively. The unadjusted and adjusted odds of poor mental health also decreased significantly among males by approximately 26% and 31%, respectively, compared to females. Crude (OR= 0.74, 95% CI: (0.67-0.82), p<0.001) & adjusted (OR=0.69, 95% CI: (0.61-0.77), p<0.001), respectively.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | The risk of poor mental health (Estimated at a cut-off point = 56) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | ||

| Age | 18-35 years | - | - |

| 36-50 years | 0.83 (0.74-0.93, p=0.002) | 0.83 (0.71-0.97, p=0.016) | |

| More than 50 years | 0.59 (0.48-0.73, p<0.001) | 0.65 (0.50-0.83, p=0.001) | |

| Gender | Female | - | - |

| Male | 0.74 (0.67-0.82, p<0.001) | 0.69 (0.61-0.77, p<0.001) | |

| Country | Algeria | - | - |

| Egypt | 1.21 (0.97-1.52, p=0.096) | 1.43 (1.11-1.85, p=0.005) | |

| Iraq | 0.99 (0.79-1.24, p=0.940) | 1.13 (0.89-1.44, p=0.314) | |

| Jordan | 1.11 (0.87-1.41, p=0.392) | 1.28 (0.98-1.67, p=0.066) | |

| Kuwait | 0.24 (0.01-2.47, p=0.238) | - | |

| Lebanon | 0.31 (0.04-1.90, p=0.206) | - | |

| Libya | 0.97 (0.78-1.20, p=0.765) | 0.98 (0.77-1.24, p=0.852) | |

| Morocco | 0.00 (NA-454884.75, p=0.925) | - | |

| Palestine | 0.70 (0.56-0.88, p=0.002) | 0.67 (0.52-0.85, p=0.001) | |

| Qatar | 0.94 (0.09-20.30, p=0.960) | - | |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.29 (0.23-0.36, p<0.001) | 0.29 (0.22-0.37, p<0.001) | |

| Sudan | 1.30 (1.04-1.63, p=0.023) | 1.28 (1.00-1.65, p=0.055) | |

| Syria | 0.60 (0.48-0.74, p<0.001) | 0.70 (0.55-0.90, p=0.005) | |

| Tunisia | 1.00 (0.80-1.25, p=0.986) | 0.93 (0.73-1.20, p=0.594) | |

| Yemen | 0.71 (0.57-0.87, p=(0.001) | 0.77 (0.61-0.96, p=0.023) | |

| Marital status | Divorced | - | - |

| Married | 0.60 (0.44-0.81, p=0.001) | 0.68 (0.48-0.94, p=0.021) | |

| Single | 0.66 (0.48-0.88, p=0.006) | 0.58 (0.41-0.82, p=0.002) | |

| Widower | 0.95 (0.53-1.74, p=0.856) | 1.09 (0.58-2.12, p=0.786) | |

| Educational level | College student | - | - |

| High school/Diploma | 1.07 (0.93-1.24, p=0.330) | 1.00 (0.85-1.17, p=0.996) | |

| Post graduate | 0.86 (0.77-0.95, p=0.004) | 0.90 (0.79-1.03, p=0.128) | |

| Presecondary | 1.00 (0.75-1.34, p=0.999) | 1.12 (0.81-1.55, p=0.505) | |

| Location | Camps | - | - |

| Rural | 0.94 (0.63-1.37, p=0.741) | 0.93 (0.54-1.57, p=0.800) | |

| Urban | 0.74 (0.51-1.07, p=0.119) | 0.81 (0.47-1.35, p=0.428) | |

| Migrant status | Citizen | - | - |

| Migrant | 0.99 (0.76-1.29, p=0.957) | 1.15 (0.85-1.57, p=0.374) | |

| Resident | 1.31 (1.19-1.45, p<0.001) | 1.46 (1.30-1.65, p<0.001) | |

| Work in the medical field | No | - | - |

| Yes | 0.92 (0.84-1.01, p=0.095) | 0.90 (0.80-1.01, p=0.073) | |

| Current living situation. | I live alone | - | - |

| I live in a shared household | 1.41 (1.13-1.75, p=0.002) | 1.11 (0.87-1.42, p=0.391) | |

| I live with my family | 1.21 (1.02-1.44, p=0.028) | 1.00 (0.82-1.22, p=0.961) | |

| Persons need the care | 5 or more | - | - |

| Less than 5 | 1.17 (1.03-1.34, p=0.016) | 1.01 (0.87-1.17, p=0.930) | |

| Nobody | 0.92 (0.80-1.06, p=0.272) | 0.71 (0.60-0.85, p<0.001) | |

| Job condition | I work for my own account | - | - |

| Part -time employee, a short -term contract employee | 1.23 (1.07-1.41, p=0.003) | 1.06 (0.90-1.25, p=0.468) | |

| Permanent Employee | 0.79 (0.70-0.88, p<0.001) | 0.89 (0.76-1.04, p=0.142) | |

| Workplace before the pandemic | Fieldwork | - | - |

| House | 1.24 (1.07-1.43, p=0.004) | 1.36 (1.10-1.67, p=0.004) | |

| House/Fieldwork | 0.19 (0.01-1.49, p=0.150) | - | |

| Office | 0.95 (0.85-1.07, p=0.428) | 1.11 (0.90-1.35, p=0.331) | |

| Office/Fieldwork | 0.92 (0.39-2.35, p=0.862) | - | |

| Office/House | 0.28 (0.01-2.98, p=0.305) | - | |

| Office/House/Fieldwork | 2.84 (0.46-54.57, p=0.340) | - | |

| Workplace during the pandemic | Fieldwork | - | - |

| House | 0.96 (0.84-1.10, p=0.571) | 0.80 (0.65-0.98, p=0.029) | |

| House/Fieldwork | 426406.70 (0.00-NA, p=0.957) | - | |

| Office | 0.98 (0.86-1.12, p=0.809) | 0.97 (0.78-1.21, p=0.792) | |

| Office/Fieldwork | 426406.70 (0.00-NA, p=0.961) | - | |

| Office/House | 0.96 (0.29-3.67, p=0.945) | - | |

| Office/House/Fieldwork | 1.09 (0.29-5.20, p=0.899) | - | |

| The economic situation. | Above average income | - | - |

| Above low income | 1.96 (1.65-2.34, p<0.001) | 1.59 (1.30-1.94, p<0.001) | |

| Average income | 1.32 (1.15-1.51, p<0.001) | 1.13 (0.97-1.32, p=0.109) | |

| High income | 0.55 (0.43-0.72, p<0.001) | 0.51 (0.39-0.68, p<0.001) | |

| Low income | 1.92 (1.62-2.28, p<0.001) | 1.51 (1.24-1.84, p<0.001) | |

The adjusted odds of poor mental health increased significantly among Egyptian participants by approximately 43% compared to Algerians (OR=1.43, 95% CI: (1.11-1.85), p=0.005). Meanwhile, the unadjusted odds decreased significantly among Palestinians, Saudi Arabians, Syrians & Yemenis by approximately 30%, 71%, 40% & 29%, respectively, and after adjustment decreased significantly by approximately 33%, 71%, 30% & 23%, respectively, compared to Algerians. Crude (OR= 0.70, 95% CI: (0.56-0.88), p=0.002), (OR=0.29, 95% CI: (0.23-0.36), p<0.001), (OR=0.60, 95% CI: (0.48-0.74), p<0.001) & (OR=0.71, 95% CI: (0.57-0.87), p=0.001), respectively. Adjusted (OR= 0.67, 95% CI: (0.52-0.85), p=0.001), (OR=0.29, 95% CI: (0.22-0.37), p<0.001), (OR=0.70, 95% CI: (0.55-0.90), p=0.005) & (OR=0.77, 95% CI: (0.61-0.96), p=0.023), respectively. However, among Sudanese, the unadjusted odds increased significantly by approximately 30%, while after adjustment, they increased but nonsignificant by approximately 28% compared to Algerians. (OR=1.30, 95% CI: (1.04-1.63), p=0.023) & (OR=1.28, 95% CI: (1.00-1.65), p=0.055), respectively.

The in-adjusted odds of poor mental health also decreased among married and single participants by approximately 40% and 34%, respectively, while after adjustment, they also decreased significantly by approximately 32% and 42%, respectively, compared to divorced participants. Crude (OR=0.60, 95% CI: (0.44-0.81), p=0.001) & (OR=0.66, 95% CI: (0.48-0.88), p=0.006), respectively. Adjusted (OR=0.68, 95% CI: (0.48-0.94), p=0.021) & (OR=0.58, 95% CI: (0.41- 0.82), p=0.002), respectively.

The unadjusted odds of poor mental health decreased significantly among postgraduates by approximately 14%, while after adjustment, the odds also decreased but nonsignificantly by approximately 10% compared to college students. (OR=0.86, 95% CI: (0.77-0.95), p=0.004) & (OR=0.90, 95% CI: (0.79-1.03), p=0.128), respectively. The unadjusted and adjusted odds of poor mental health increased significantly among resident participants by approximately 31% and 46%, respectively, compared to citizens. (OR=1.31, 95% CI: (1.19-1.45), p<0.001) & (OR=1.46, 95% CI: (1.30-1.65), p<0.001), respectively. Additionally, the unadjusted odds increased significantly among participants living in a shared household and participants living with their family by approximately 41% and 21%, respectively, compared to participants living alone. (OR=1.41, 95% CI: (1.13-1.75), p=0.002) & (OR=1.21, 95% CI: (1.02-1.44), p=0.028), respectively.

The unadjusted odds of poor mental health increased significantly by approximately 17% among participants taking care of less than 5 persons compared to participants taking care of 5 persons or more (OR= 1.17, 95% CI: (1.03-1.34), p=0.016). The adjusted odds decreased significantly among participants who did not take care of anybody by approximately 29% compared to participants taking care of 5 persons or more (OR=0.71, 95% CI: (0.60-0.85), p<0.001).

The unadjusted odds of poor mental health increased significantly among part-time employees by approximately 23% while decreasing significantly among permanent employees by approximately 21% compared to participants working independently. (OR=1.23, 95% CI: (1.07-1.41), p=0.003) & (OR=0.79, 95% CI: (0.70-0.88), p<0.001), respectively. Additionally, both the unadjusted and adjusted odds increased significantly among participants mainly working in the house before the pandemic by approximately 24% and 36%, respectively, compared to participants working in the fieldwork before the pandemic (OR=1.24, 95% CI: (1.07-1.43), p=0.004) and (OR=1.36, 95% CI: (1.10- 1.67), p=0.004), respectively). However, only the adjusted odds of poor mental health decreased significantly among the participants working at home during the pandemic by approximately 20% compared to participants working at the fieldwork during the pandemic (OR=0.80, 95% CI: (0.65-0.98), p=0.029).

Regarding the economic situation, the unadjusted odds of poor mental health increased significantly among participants with low income and above low income by approximately 92% and 96%, respectively, and after adjustment, the odds increased significantly by approximately 51% and 59%, respectively, compared to participants with above average income. Crude (OR=1.92, 95% CI: (1.62-2.28), p<0.001) & (OR=1.96, 95% CI: (1.65-2.34), p<0.001), respectively. Adjusted (OR=1.51, 95% CI: (1.24-1.84), p<0.001) & (OR=1.59, 95% CI: (1.30-1.94), p<0.001), respectively. Additionally, only the unadjusted odds increased significantly among participants with average income by approximately 32% compared to participants with above average income (OR= 1.32, 95% CI: (1.15-1.51), p<0.001). Among participants with high income, the unadjusted and adjusted odds of poor mental health decreased significantly by approximately 45% and 49%, respectively, compared to participants with above average income (OR=0.55, 95% CI: (0.43-0.72), p<0.001) and (OR=0.51, 95% CI: (0.39- 0.68), p<0.001), respectively.

Discussion

The COVID-19 epidemic has afflicted millions of individuals throughout the world, with many of them suffering tragic effects [12]. The pandemic's progress has been substantially impacted by societal inequities in the incidence of chronic illnesses and social determinants of health (including employment) [13]. The world of work has been severely impacted, not only because of the large number of cases among the working population but also because of effects resulting from government policies and measures to combat the pandemic (e.g., "lockdown," forced teleworking...), as well as effects resulting from labor management practices, which have resulted in a deterioration of working conditions, albeit unevenly[14]. As a result, the COVID-19 pandemic poses a significant threat to occupational health. Many vocations need close contact or physical proximity with other people, posing a higher risk of exposure and infection, while others allow one to work from home, significantly lowering the risk of infection.

For instance, this was the first study to examine the impact of COVID-19 on working conditions in the MENA region. The present study aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on working conditions for employees. The first objective of the study was to assess the perceived impact and self-reported changes related to COVID-19.

The majority of studies to date have mostly focused on the negative consequences of the COVID-19 problem. [7, 8, 15-17], In line with our data, it was found that only 19.8% of the study participants reported that their health status had worsened during the pandemic. Approximately 64.9% had slept badly and restlessly, and they were suffering from depression and nervousness with a risk of poor mental health with increased consumption of opioids, pain killers and sleeping pills. In line with our data, employees whose contract had been reduced or terminated due to the lockdown measures are particularly vulnerable to developing mental health problems [16, 18]. The health of workers has deteriorated significantly: more than one-third of the salaried population claims that their general health status has deteriorated during the pandemic; the use of tranquillizers and opioid analgesics has more than doubled compared to the pre pandemic situation, and a significant percentage of those who were already users have increased their dose. On the other hand, the ERP-2016 estimated that the percentage of subjects who reported frequently or frequently increased their dose. [19] and those who were at risk of poor mental health 23.7% [20]. This implies that the number of workers with extremely regular sleep disorders has nearly tripled since 2016, and the number of workers at risk of poor mental health has nearly doubled. Multiple factors contribute to the deterioration of mental health in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among work-related causes will surely be the increase in exposure to high strain [19], employment instability and money stress are both sources of uncertainty [21], fear of becoming infected, etc., as well as the increase in social isolation and loneliness [22]. In any event, it is clear that if this situation persists, the consequences for workers' health might be severe. Although the degree of harmfulness for the collection of variables investigated is typically high, there are significant inequalities: manual laborers, women, young individuals, and those with lower earnings are unquestionably worse off.

Young people, who already have the highest levels of precariousness and the associated job insecurity and job destruction, are likely to be the pandemic's principal occupational victims, since they risk having their whole working lives impacted by the current scenario, becoming "the lockdown generation." [23].

Salary is also revealed as a prominent axis of inequality, since it is highly related to most of the items analyzed, such as going to work with symptoms corresponding to COVID-19, implying that remaining at home is not an option for many individuals due to financial constraints. Furthermore, additional studies have revealed the susceptibility of other occupational categories, such as migrant workers, many of whom are engaged in low-skilled jobs and live in substandard housing [24].

There were some limitations in our study because only individuals who could access the internet could participate in online surveys, there is a chance that selection bias was introduced. As a result, the findings should not be generalized too widely. Also, the multicultural context, the disparity in policies, and the compliance with public health initiatives that varied between participating countries may also have an effect on the variables under investigation (psychological distress, fear, and ways of coping). To reduce the possibility of confounding effects, we modified the variable "country" throughout the multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

The findings given here paint a very alarming picture of the quality of working conditions and the health of employees living in the MENA region, at the height of the pandemic. In general, we observe harmful working conditions and health indicators with very important deterioration compared to available references. In general, we see unfavorable working conditions and health indicators that have dramatically deteriorated in comparison to available references. The situation is also worse in some groups, even though it appears to be poor overall. Inequalities in working conditions and health that are based on class, gender, or age may have been made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic as a result. It would be very concerning if both the working conditions and the health of the workers continued to be significantly worse than before the pandemic, so in the future, once the pandemic has been defeated, the worsening of these conditions should be reversed and the extent to which it returns to the previous situation should be evaluated.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

KE, researched literature, questionnaire design, and websurvey design, coordinate and monitor the data collection process with collaborators, wrote the first draft of the manuscript; NKE, questionnaire design, and web-survey design, supervised the data collection process, checked writing; RS, data interpretation, organizing and data arrangement, coded data, involved in statistical analysis, designed figures, checked writing; PH, manuscript editing; NH, supervised all steps, checked writing, and approved methodology; HAA, MAAR, ME, DNA, EAM, MSS, DJA, MJ, EAZ, AMN, MA, YAAA, MAA, KE, MSAA, SHKAA, AMS, WA, DAA, KHA, HYA, JH, OE, NAH, AK, DHHD, IB, IMGA, GMGA, HTA, AK, HMJA, OA, AK, MA, MTEE, MMA, AF, AD, AM, AB, SMA, ZYA, HSH, MAM, FAA, MAA, collected the data. ZM, AG, OA, AK, MA, MAN, YAAA get ethical approval. KE, DAAD, AK, HMJA translate the Spanish questionnaire. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable

Acknowledgement

Not applicable

References

- Organization WH (2020) COVID 19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). Global research and innovation forum: towards a research roadmap.

- Chakraborty C (2020) SARS-CoV-2 causing pneumonia-associated respiratory disorder COVID-19: diagnostic and proposed therapeutic options. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 24: 4016-4026.

- Kniffin KM (2021) COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am Psychol 76: 63-77.

- Koh DHP (2020) Occupational health responses to COVID-19: What lessons can we learn from SARS?

- Brooks SK (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The lancet 395: 912-920.

- Fofana NK (2020) Fear and agony of the pandemic leading to stress and mental illness: An emerging crisis in the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Psychiatry Res 291:113-230.

- Rodríguez-Rey RH, Garrido-Hernansaiz S, Collado S (2020) Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Frontiers in psychology 1540.

- Ahrendt D (2020) Living, working and COVID-19.

- EDADES I, EDADES 2017-2018: Encuesta sobre alcohol y otras drogas en España (EDADES), 1995-2017. Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas. Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones. Secretaría de Estado de Servicios Sociales. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Madrid, 2018.

- Vilagut G (2005) El Cuestionario de Salud SF-36 español: una década de experiencia y nuevos desarrollos. Gaceta sanitaria 19: 135-150.

- Burr H (2019) The third version of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Safety and health at work 10: 482-503.

- Yuki KM, Fujiogi S, Koutsogiannaki (2020) COVID-19 pathophysiology: A review. Clin Immunol 215:108-427.

- Bick A (2020) Work from home after the COVID-19 Outbreak. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Research Department.

- Capano G (2020) Policy design and state capacity in the COVID-19 emergency in Italy: if you are not prepared for the (un) expected, you can be only what you already are. Policy and Society 39: 326-344.

- Wang C (2020) Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health17:17-29.

- Qiu J (2020) A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr 33(2): 100-213.

- Sibley CG (2020) Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am Psychol 75: 618- 630.

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria N (2020) Psychological symptoms during the two stages of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak: an investigation in a sample of citizens in Northern Spain. Front Psychol 11: 21-16.

- Salas-Nicas S (2020) Job insecurity, economic hardship, and sleep problems in a national sample of salaried workers in Spain. Sleep Health 6: 262-269.

- Salas-Nicás S (2018) Cognitive and affective insecurity related to remaining employed and working conditions: their associations with mental and general health. J Occup Environ Med 60: 589- 594.

- Pelletier KR (2009) A review and analysis of the clinical and cost-effectiveness studies of comprehensive health promotion and disease management programs at the worksite: Update VII 2004-2008. Journal of

- Holmes EA (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry 7: 547-560.

- Organization IL (2020) ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Updated estimates and analysis. Int Labour Organ

- Koh D (2020) Migrant workers and COVID-19. Occup environ med 77(9): 634-636.

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

J Occup Health 62:121-128.

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

J Occup Environ Med 51:822- 837.

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Citation: Henry J, et al. (2022) Working Conditions and Health in MENA Region during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Keeping an Eye on the Gap. Occup Med Health 10: 431. DOI: 10.4172/2329-6879.1000431

Copyright: © 2022 Henry J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1735

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Dec 04, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1537

- PDF downloads: 198