Women’s Critical Mobilization, Critical Assessment of their Democracies and the Treatment of Gender Inequality in their Democracies

Received: 29-Jan-2018 / Accepted Date: 27-Jun-2018 / Published Date: 03-Jul-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2169-0170.1000241

Abstract

A large body of case study research shows that democratic transitions improve gender equality when a higher level of women participate in the movements that support the transition, and they believe that the protection of women’s rights is absolutely essential to the development of democracy in their countries. Building on this case study research, this article evaluates the relationships between female critical mobilization, female critical assessment and democracies’ treatment of gender inequality with data from a large, diverse set of democracies. The results support a chain of relationships that run from female critical mobilization, to female critical assessment, to female critical expectations to democratic treatment of gender inequality and suggest that future research should focus on women’s understanding of their rights as democratic rights, the importance women attribute to democratic institutions as mechanisms for improving gender inequality, the extent to which women support global and local activism on behalf of women’s rights as part of a larger democratization frame and the effectiveness with which women use democratic institutions to improve gender inequality within their nations.

Keywords: Gender inequality; Gender equality; Women’s rights; Democracy

Introduction

A large body of case-study research shows that democratic transitions improve gender equality when a higher level of women participate in the movements that support the transition, and they believe that the protection of women’s rights is absolutely essential to the development of democracy in their countries [1-4]. When women participate in social movements they garner the skills and motivation to become active claimants for political change. When women see women’s rights as fundamental to the achievement of democracy, they are more likely to link gender inequality to a democratic deficit during the transition phase. Women with this elite-challenging experience and this understanding of democracy become critical of a lack of ‘democraticness’ in their countries, expect more and demand more. This increases the responsiveness of governing elites and leads to lower levels of gender inequality in their new democracies. Thus, the case study literature supports a chain of relationships that run from female critical mobilization, to female critical assessment, to female critical expectations to democratic treatment of gender inequality.

While there is support for this chain of relationships in the case study literature, without larger, systematic, cross-national comparisons, it is unclear whether these findings generalize across a more diverse set of democracies [3]. A clear problem is that many of the case studies focus on the benefits of women’s development of critical democratic expectations at the time of democratic transition, and questions remain in the literature as to whether this continues to have influence as power shifts from critical social movements to ‘normalized political channels’ in the post-transition phase [4,5].

Yet, the broader democratization literature suggests that the development of women’s critical expectations should influence gender inequality in countries at all stages of democratization. General theories of democracy that explain the variation in democratic effectiveness from developing to established democracies emphasize the perpetual importance of citizens’ critical social mobilization and understanding of democracy relative to the inequalities they witness and experience in their day to day lives [6-8]. According to this view, how citizens understand democracy and whether they engage in elite-challenging behavior not only fosters transitions to democracy, but is essential to increases in democratic effectiveness in post-transition phases [8].

We argue that the importance that women give to women’s rights in their understanding of democratic justice and their engagement in critical social mobilization operates as a natural microcosm under this perspective, helping us understand the more specific variation in the treatment of gender inequality across the spectrum of the world’s democracies. Under this perspective, women’s understanding of democracy and their engagement in elite-challenging behavior fuels the development of critical female citizens who critically assess the democraticness of their countries relative to their countries’ supply of women’s rights, this generates expectations of what democracy should achieve as concerns gender equality, which fuels demand. The strength of this female demand is crucial to democracies’ continual treatment of gender inequality in both transition and post-transition phases.

To test these assumptions this article evaluates the following questions with data from a large, diverse set of democracies:

1) In democracies where women see women’s rights as absolutely essential to democratic achievements and elite-challenging action is high among women, are women more critical of the ‘democraticness’ of their countries relative to their countries’ supply of women’s rights?

2) Is gender inequality lower in democracies where the level of women who are critical of their democracies is higher?

As one can see from these questions, this study has data to look at the relationships between three out of four links in the chain: female critical mobilization, female critical assessment and democracies’ treatment of gender inequality. Due to data limitations, we cannot measure and evaluate a role for female democratic expectations but presume that this is a key mechanism that runs from critical assessment to the actual treatment of gender inequality in democracies. Before turning to this analysis, however, we first build hypotheses based on the literature and introduce other factors likely to impact democracies’ treatment of gender inequality.

Literature Review

It is no secret that one of the areas where democracies tend to be most ineffective is in the adoption and enforcement of rights for women. Reflecting on the wave of liberal democratization that swept the globe from the late 80s through the 90s, Bystydzienki and Sekhon [1] remark:

The recent wave of liberal democratization generally has not served women well. In many parts of the world where democratization is said to be taking place, women, who comprise at least half of the population, have benefitted less from the changes than men have.

Several case studies tell us how the gendered outcomes of democratization vary across nations [1-4]. For instance, analysis of Ghana and Nigeria shows that democratic transition failed to foster gender-equitable outcomes similar to South Africa [2,3]. Indeed, according to Hassim [9], “[in South Africa] the transition to democracy… did not lead to the marginalization of women but rather to the insertion of gender equality concerns into the heart of democratic debates.”

Related findings also separate cases in Latin America [10,11]. For instance, studies show that feminist changes occurred in Argentina and Chile whereas the Salvadoran state remained highly masculine with democratic transition [2,3,12].

When we add the eastern European experience, where studies find that democratization did little to improve gender equality [4,13,14], the picture becomes significantly varied.

An important explanation of this variation centers on the role of women in these processes [1-4]. The strength of women’s understanding of their democratic entitlements and their activism is emphasized. If democratization is to improve a country’s gender equality, then widespread belief, particularly among women, that women’s rights are an essential characteristic of democracy is a necessary first step. In addition, women’s participation in grassroots mobilization is equally crucial for garnering skills and developing a critical democratic mentality. Combined, women’s elite-challenging behavior and this understanding of democracy develop critical female citizens who are sensitive to what democracy ought to deliver to women. This legitimates women’s criticism and political action in response to conditions of gender inequality at the time of transition [1].

However, several scholars note that the issue of women’s inequality is often neglected in the post-transition stage, as power shifts away from oppositional social movements to the more ‘normalized’ democratic channels [4,5]. As an explanation of the post-transition neglect, they isolate the following problem with the conceptualization of democracy’s core elements. The idea that women’s rights are an essential characteristic of democracy is rarely central to the larger conception of democracy that, post-transition, guides the subsequent development of institutions and policies [4,15-19]. Instead, it is more typical for the adoption and support of a minimal, electoral understanding of democracy to be emphasized as institutions and policies develop. This understanding of democracy reduces the essential characteristics of democracy to periodic, competitive elections, and explicit reference to gender is rarely included in these electoral definitions [16,17].

According to Waylen [4] and others1 this minimal definition illegitimates “wider definitions of democracy couched in terms of the real distribution of power in society” (332). The ‘electoral minimalism’ does not go far enough to support the achievement of gender parity through women’s political, economic and social rights as essential to democracy. As politics normalize in the post-transition phase, this produces a belief system of ‘democratic’ demands and supports prone to gender neutrality and neglect of the issue of women’s inequality [17]. The emphasis on democracy’s universal and equal treatment depoliticizes remaining gender-based inequalities post-transition and diminishes the strength of women’s critical mobilization over remaining gender inequalities [18].

These problems with electoral reductionism are a key reason scholars increasingly pay attention to women’s activism and advocacy through extra-electoral modes of pressure such as participation in informal political efforts and organizations [20-23]. Research suggests that non-formal engagement may be easier for women and correspond more strongly to their own definitions of (good) citizenship engagement [24,25]. A large body of research on the non-formal arena shows particular interest in the strength of societies’ women’s movements. According to Banaszak [26], “Social movements are usually defined as a mixture of informal networks and organizations that make “claims” for fundamental changes in the political, economic or social system, and are “outside” conventional politics, and utilize unconventional or protest tactics.” Beckwith [27] specifies that women’s movements are “self-consciously distinguished by women’s gendered identity claims that serve as the basis for activism and mobilization”.

Thus, in various post-transition stages, it is plausible that all democracies profit from women’s active embrace of gender equality as essential to democracy and extra-electoral modes of participation. These are likely key sources for the development a critical assessment of democracy relative to its supply of gender equality and, in turn, critical democratic expectations under which female citizens are more likely to demand that democracies do more for female empowerment. Therefore, while analysis in the literature has largely focused on democratic transitions, even in established democracies, women’s understanding of their rights, their level of critical social mobilization and their resulting level of criticism of the ‘democraticness’ of their countries should also influence their countries’ level of gender inequality.

More general theories of democratization, indeed, suggest that female citizens’ criticism of their democracies should continue to matter as an influence of the gendered outcomes of democracies at all levels of democratization. For instance, research shows that the number of “critical citizens” is rising in developed democracies producing citizens that are increasingly critical of authority and hold elites to higher democratic standards [28,29]. Furthermore, even in advanced societies, one cornerstone of the supply of good democratic governance for women is women’s effectiveness in demanding that public authorities “explain and justify their efforts (or failures) to advance women’s rights” [30]. The expectations women develop based on their critical assessment of their democracies’ supply of women’s rights plays a crucial role in their achievement of that level of accountability.

Moreover, in the most advanced, postindustrial democracies, where democracy has achieved the highest levels of gender equality, there is evidence of a fundamental shift in values occurring among younger generations that includes increasing support for gender equality as an important political issue [20,31]. This support is even more pronounced among younger women [20]. Indeed, Alexander and Coffé [20] find that it is in countries in their global sample with the longest gender egalitarian cultural legacy, where young women appear to be pulling away from young men the most in terms of their confidence in the women’s movement and level of support for women’s role in politics.

There is also generational evidence of a fundamental shift in the style of political behavior [32]. The use of more autonomous forms of political influence including elite challenging acts is increasing [33,34]. Some argue that this has fostered the most critically mobilized citizenry powerholders have ever faced in democracies [35,36], and evidence shows that the level of citizens’ critical orientations improves the monitoring and enforcement of rights in their countries [8,37], including women’s rights [38]2. Therefore, when we focus on gender inequality and women’s rights in particular, it follows that the posited chain running from women’s critical mobilization to women’s critical assessment to women’s critical expectations is potentially a powerful interlinkage as concerns the supply of gender equality even in the most advanced democracies.

Thus, while the evaluation and evidence has focused on democratic transitions, there are good reasons to expect this development to have a positive impact on the treatment of gender inequality at all stages of democratization. This calls for more systematic analysis across a larger, more diverse set of democracies. From this discussion, we derive hypotheses that we subject to cross-national, multivariate analysis.

One set of hypotheses posit a link between the level of women’s critical mobilization, both in terms of orientation and behavior, and their level of critical assessment of their democracies’ treatment of gender inequality. This is specified in H1 as a relationship we would expect to observe across countries. To compliment the country-level, we also bring in a micro-foundational perspective on this front. Here, we posit H1M, which specifies this as a relationship we would also expect to observe at the individual-level among women.

H1: The higher the percentage of women who give the highest importance to women’s rights as an essential characteristic of democracy and engage in elite-challenging behavior, the higher the level of women’s critical democratic assessment (higher percentage of women who underrate the ‘democraticness’ of their democracies relative to the supply of women’s rights in their democracies) per country.

Microfoundation hypothesis, H1M: Women who give highest importance to women’s rights and engage in elite-challenging behavior are more likely to hold critical democratic expectations and this relationship is stronger in countries where women’s critical democratic expectations are more widespread.

The final hypothesis posits a link between the level of women’s critical democratic assessment across democracies and the level of gender inequality across democracies.

H2: The higher the level of women’s critical democratic assessment, the lower the level of gender inequality in their democracies.

Before turning to the analysis of these hypotheses, the following section introduces a strong rival hypothesis to H1 and H2 and five key controls in the analysis of both hypotheses: countries’ level of development, religion, democracy, state capacity and the global political linkage.

A rival influence: women’s conventional political engagement

It is also plausible to expect that the higher the percentage of engaged voters who are women the stronger the level of women’s critical democratic expectations and/or the lower the level of gender inequality in their countries. This would follow a more conventional democratic model of how groups influence government in their democracies. As a challenge to H1 and H1M, it could be that women’s engagement with the conventional channels of democratic influence more strongly increases the level of their critical democratic expectations when compared to their understanding of their democratic entitlements and their level of elite challenging behavior. As a challenge to H2, it could be that women’s engagement with the conventional channels of democratic influence more strongly decreases their democracies’ level of gender inequality when compared to the level of women’s critical democratic expectations in their countries. Thus, we look at the percentage of women who are both highly interested in politics and vote to account for these rival hypotheses.

Controls: human development, religious tradition, level of democracy, state capacity and global political linkage

Human development: A large body of evidence shows that the growth in human development through societal modernization is a strong explanation of the global, cross-national variation in countries’ level of gender inequality [31]. According to Inglehart and Norris [31], as societies modernize, improvements in countries’ level of education, the professionalization of the workforce, living conditions, scientific innovation, and the mass media breakdown traditional authority structures in religion and the family that perpetuate women’s public exclusion. Thus, in less developed democracies, with agrarian and industrial economies, the lower levels of human development create a cultural barrier to the development of gender egalitarian orientations and the practice of gender equality.

Therefore, it is highly likely that as countries develop, women’s critical democratic expectations also improve, and it could be the increase in objective conditions associated with development rather than this improvement in attitudes that matters for countries’ level of gender inequality. It is therefore important to control for countries’ level of development to determine whether these attitudes among women, while plausibly linked to human development, are independently influential of democracies’ treatment of gender inequality.

Religious tradition: In addition to human development, a broader literature identifies religion as a primary agent of gender role socialization [39] and a major variable in countries’ treatment of gender inequality [31]. There is evidence of support for traditional and subordinate roles for women in all religions; however, countries with a non-Protestant religious heritage are especially prone to patriarchal beliefs and high levels of gender inequality [31,40]. Thus, this study evaluates countries’ religious heritages as another key control of the relationship between women’s critical democratic expectations and democracies’ level of gender inequality.

Level of democracy: Through the provision of political liberties and civil rights, democracy supports higher levels of political criticism and political participation [41]. The support for human autonomy and tolerance of social diversity nurtured through the institutionalization of these rights and liberties creates a political climate that is less conducive to gender inequality.

In this case, much like the variation in human development, it is highly likely that as countries’ levels of democracy improve, women’s critical democratic expectations also improve, and it could be these increases in democracy rather than improvements in attitudes matter for countries’ levels of gender inequality. It is therefore important to control for countries’ levels of democracy to determine whether these attitudes among women, while plausibly linked to democratic development, are independently influential of democracies’ treatment of gender inequality.

State capacity: There are many instances where countries’ adoption of formal rights in reaction to various types of gender inequality does not match the level of “everyday” patriarchal, discriminatory practice in those counties. Many note that this is a problem of state capacity. Countries are limited in their capacity to enforce women’s formal rights to the extent that they are recognized and practiced on a day to day basis. Indeed, broader research on democratization, finds that the capacity of states to enforce political and civil rights separates effective from ineffective democracies [42]. Thus, state capacity is an important control variable in the assessment of the relationship tested in H2, the relationship between women’s critical democratic expectations and democracies’ treatment of gender inequality.

Global political linkage: Theories of international influence point out that nations are interconnected through the international arena [43]. This international interconnectedness, particularly that facilitated through political linkages, has strengthened domestic actors’ fight for gender equality in their countries [44,45] and, in some cases, has also been a direct influence of change in countries’ level of gender equality [46-50]. Thus, the extent of countries’ global political connectedness is controlled in the analysis of both hypotheses [51-54].

Data

Hypothesized variables

To evaluate H1 and H1M, which capture the critical mobilization/ critical assessment link, we measure three variables: women’s belief that women’s rights are essential to democracy (critical mobilization orientation), women’s engagement in elite-challenging behavior (critical mobilization behavior) and the extent to which women are critical of the democraticness of their democracies (critical assessment). The fifth wave of the World Values Surveys (WVS) is a primary data source for all three of these variables.

In collaboration with the EVS (European Values Study), the WVS has carried out representative national surveys in 97 societies containing almost 90 percent of the world’s population. The surveys ask questions that tap what people want out of life and what they believe, including several questions on political beliefs and behaviors. Data was collected for the fifth wave in 57 countries from 2005-2008. Since we are interested in countries that have achieved at least a minimal level of democracy, of these 57 countries, we looked only at those countries that were considered partly free according to Freedom House. For the three variables evaluated in H1, data was available for 44 countries classified by Freedom House as partly free or free.

As a measurement of the critical orientation component of the critical mobilization variable, the WVS asks the following question:

“Many things may be desirable, but not all of them are essential characteristics of democracy. Please tell me for each of the following things how essential you think it is as a characteristic of democracy. Use this scale where 1 means “not at all an essential characteristic of democracy” and 10 means it definitely is “an essential characteristic of democracy”. Women have the same rights as men.”

To begin building the measure of critical mobilization, we measure the percentage of women per country that rate women’s rights as most essential, a 10 on the essential characteristic scale. This tells us what percentage of women believes that the unequal treatment of women is fundamentally undemocratic, which the literature identifies as an important pre-condition for developing expectations concerning what democracy ought to deliver when it comes to gender inequality.

To compliment the country-level perspective with a micro-level approach, we create a dummy variable at the individual-level. We rescale the respondent category scores so that, responses ranging between 1 and 9 are scored 0 and responses on 10 are scored 1.

In terms of country percentages, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is 17.8 percent represented by Malaysia and the maximum is 87.5 percent represented by Andorra. The mean is around 60 percent, a percentage that comes close to the percentages observed in Morocco and Turkey.

As a measurement of the critical behavior component of the critical mobilization variable, the WVS asks the following question:

“I’m going to read out some forms of political action that people can take, and I’d like you to tell me, for each one, whether you have done any of these things in the last five years: signing a petition, joining in boycotts, or attending peaceful demonstrations.”

To complete the measure of critical mobilization, we measure the percentage of women per country that indicate that they have participated in one or more of these forms of political action in the last five years. The literature suggests that engagement in these kinds of elite-challenging political actions also contributes to the development of women’s understanding of democracy and higher expectations for democracy’s treatment of gender inequality.

To capture this under the micro foundational perspective, we create a variable per respondent by adding their responses to participating in petitions, boycotts and demonstrations, where participation in one of these is scored 1 and no participation 0. This creates a scale ranging from 0-3 per respondent.

In terms of country percentages on this critical behavior component, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is 2 percent represented by Thailand and the maximum is 50 percent represented by Sweden. The mean is around 20 percent, a percentage represented by Argentina.

Overall, H1 anticipates that combined, as a measure of critical mobilization, the higher the percentages of women who believe women’s rights are absolutely essential to democracy and the higher the percentages who have participated in elite-challenging behavior in a democracy, the higher will be the percentages of women who critically assess the democraticness of their democracies relative to their democracies’ supply of women’s rights. Thus, to create the combined measure at the country-level, both the measure of the percentage of women who see women’s rights as an essential characteristic and the measure of the percentage of women who have engaged in one form of elite challenging behavior were rescaled to run from 0-1. Then the two variables were added.

To create the combined measure at the individual-level to test H1M, we rescaled the elite challenging action variable per respondent by dividing this by the maximum values so that the variable’s new score range runs from 0-1. This was then added with the importance of women’s rights to democracy dummy variable. This gives us a measure of the combined impact of these two variables at the individual-level.

In terms of country percentages on this combined measure, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is 0.10 represented by Malaysia and the maximum is 0.68 represented by Sweden. The mean is around a 0.40, which comes close to Romania’s score.

As a measurement of H1’s outcome variable, critical assessment, the WVS asks the following question:

“How democratically is this country being governed today? Again using a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means that it is “not at all democratic” and 10 means that it is “completely democratic,” what position would you choose?”

Women’s answers to this question are rescaled 0-1. Then, we look at the women’s rights score given to each country on the same year according to the Cingranelli and Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Dataset.3 This women’s rights score is also rescaled 0-1. We then compute the following variable for each female respondent: the country’s (actual) level of women’s rights (according to CIRI) minus female respondents’ subjective assessment of the democraticness of their country. This is the dependent variable we use in the multilevel models to test H1M. To test H1, we look at the percentage of women per country with a score greater than zero. These women underrate the ‘democraticness’ of their democracies relative to the supply of women’s rights in their democracies. It is plausible to assume that women who underrate relative to their democracies’ supply of rights will continue to challenge elites for more equality. Furthermore, it is important to note that there is not a single democracy in the world that has eradicated gender inequality in the share of economic and political power. Yet, democracy as a theoretical ideal is built on principles of justice that envision equality and fairness for citizens of a democratic system. Large systematic group inequalities such as gender-based inequalities fail to reflect this democratic ideal. Therefore, such criticalness among women is warranted in all democracies.

On the country-level, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is 3.5 percent represented by Ghana and the maximum is 96.3 percent represented by Western Germany. The mean is around 48 percent, which comes close to the United Kingdom’s percentage.

Before discussing H2, one additional country-level variable is relevant to H1M. H1M expects a cross-level interaction between the country-level of critical assessment, described above, and the strength of the relationship between critical mobilization and critical assessment at the individual-level. The idea behind this posited interaction is the following. For a given woman, whether acknowledging that women’s rights are fundamental to the concept of democracy and engaging in elite challenging behavior actually translates into a critical assessment of the democraticness of her country depends on the larger receptivity and legitimacy that such an assessment will garner among her larger community. To put it more generally, whether one’s ideas and/or actions are respected and reciprocated by others in one’s community is fundamentally important to one’s calculus of the value of raising such social criticism; in the most non-responsive of environments, this could leave an individual with nothing but social ostracism. Thus, in a country where women are generally compliant or even enthusiastic (overrate) with their democracies regardless of their democracies’ poor performance in eradicating gender inequality, a critically mobilized woman will lack the receptive female community needed for seeing the benefit of channeling this into critical assessment. In a nutshell, some feeling of (female) social solidarity is fundamentally important to making this step [8].

Assuming H1 and H1M are confirmed, H2 expects a negative country-level relationship between the variable that measures women’s critical assessment of their democracies and the actual level of gender inequality in their democracies. The level of gender inequality is measured across the 44 democracies according to the United Nations’ Development Program’s Gender Inequality Index as of 2011. According to the UNDP’s human development reports website:

The Gender Inequality Index (GII) reflects women’s disadvantage in three dimensions—reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market. The index shows the loss in human development due to inequality between female and male achievements in these dimensions. It ranges from 0, which indicates that women and men fare equally, to 1, which indicates that women fare as poorly as possible in all measured dimensions. The health dimension is measured by two indicators: maternal mortality ratio and the adolescent fertility rate. The empowerment dimension is also measured by two indicators: the share of parliamentary seats held by each sex and by secondary and higher education attainment levels. The labour dimension is measured by women’s participation in the work force. The Gender Inequality Index is designed to reveal the extent to which national achievements in these aspects of human development are eroded by gender inequality.

On this measure, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is a 0.17 represented by the Netherlands and the maximum is a 0.80 represented by Mali. The mean is around a 0.45, which comes close to Moldova and Trinidad and Tobago’s scores.

The rival variables

To measure a rival explanation to H1 and H2, namely, that what matters is the percentage of women who are engaged voters in a democracy both for the level of critical assessment among women and for the level of gender inequality across democracies, we once again draw on the fifth wave of the WVS. we look at two variables. One measures respondents’ level of political interest and the other whether respondents voted in the most recent election. The political interest variable asks respondents, “How interested would you say you are in politics?” Then, respondents have four response categories, ranging from 1 (very interested) to 4 (not at all interested). The vote variable asks respondents whether they voted in the most recent election.

To measure the percentage of women who are engaged voters across the sample of democracies, we take the percentage of women per country who responded that they were very interested in politics and voted in the last election.

According to this measure, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is 1.5 percent represented by the Malaysia and the maximum is 18.6 percent represented by Mali. The mean is around 7.6 percent, which comes close to the United Kingdom’s percentage.

Control variables

We consider five control variables: countries’ level of human development, religious tradition, level of democracy, state capacity and global political linkage. These variables are all measured in the mid- 2000s.

The measure of human development is taken as the United Nation’s Development Program’s Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI is a composite index that combines country-level data on life expectancy, mean years of schooling, expected years of schooling and gross national income per capita into an overall index that scores countries from 0 (no development) to 1.0 (full development).

According to this measure, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is a 0.32 represented by Burkina Faso and the maximum is a 0.96 represented by Norway. The mean is about a 0.79, which comes close to Brazil’s score.

Countries with a non-Protestant religious heritage are especially prone to patriarchal beliefs [31,42]. Thus, religious tradition is measured by the percentage of Protestants per country.

According to this measure, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is 0. Several countries have this value, particularly those that are homogeneously Catholic and Muslim. The maximum is 88 percent represented by Norway. The mean is around 19 percent, which comes close to the South Korea’s percentage.

Countries’ level of democracy is measured with Freedom House’s political rights and civil liberties’ index. The index is rescaled to run from 0 (no political rights or civil liberties) – 1.0 (full provision of political rights and civil liberties).

According to this measure, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is a 0.43 represented by Ethiopia and the maximum is a 1.0 represented by several countries, most of the old, advanced democracies in the sample. The mean is around a 0.86, which comes close to the score of countries at the level of Brazil and Bulgaria.

State capacity is measured according to the World Bank’s “Rule of Law” data. This includes several indicators which measure the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society. These include perceptions of the incidence of crime, the effectiveness and predictability of the judiciary, and the enforceability of contracts. Together, these indicators measure the success of a society in developing an environment in which fair and predictable rules form the basis for economic and social interactions and the extent to which property rights are protected.

According to this measure, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is a -0.79 represented by the Ukraine and the maximum is a 2.0 represented by Norway. The mean is around a 0.49, which comes close to Uruguay’s score.

To measure the final control, the countries’ level of global political linkage, we use data from the Dreher Index of Globalization. The Political Globalization Index is measured by the number of embassies and high commissions in a country, the number of international organizations of which the country is a member, the number of UN peace missions the country has participated in, and the number of international treaties that the country has signed since 1945.

According to this measure, across the sample of 44 democracies, the minimum value is a 21.3 represented by Andorra and the maximum is a 97.6 represented by France. The mean is around an 81.9, which comes close to Ukraine’s score.

Results and Discussion

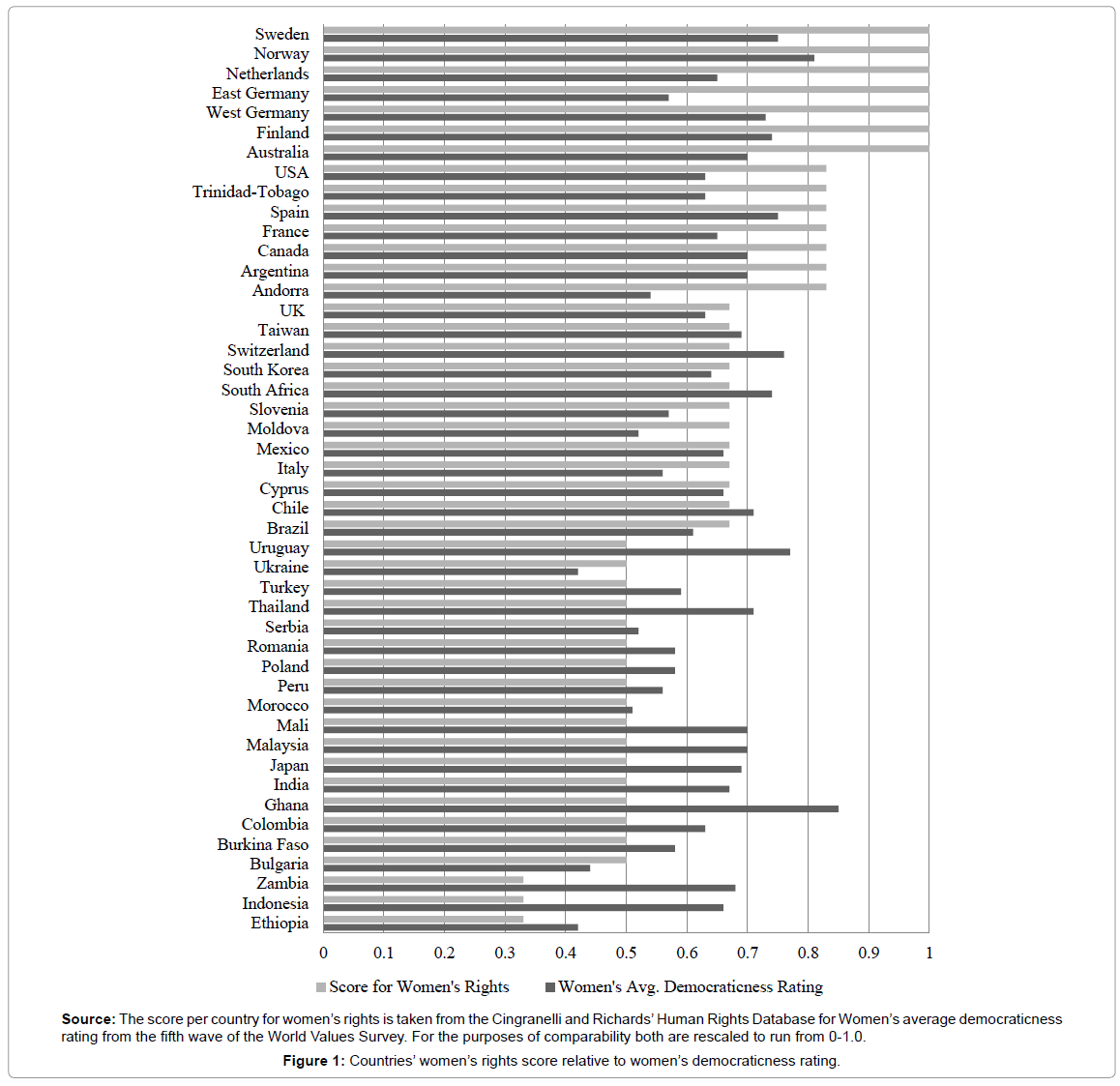

H1 predicts that the percentage of women that critically assess their democracies per country is significantly influenced by the percentage of women who see women’s rights as absolutely essential to their countries’ democratic achievement and the percentage of women who engage in elite challenging behavior. Figure 1 gives us a look into the measurement of women’s critical democratic expectations across the sample of countries analyzed in this paper (Figure 1).

The lighter upper bar per country in Figure 1 tells us how countries score in terms of their actual supply of women’s rights. The darker lower bar per country tells us women’s average rating of the democraticness of their countries. The scales of both of these measures have been standardized to make them comparable. In countries where the upper bar outdistances the lower bar women have critical democratic expectations. How far shows the strength of their critical democratic expectations. A large percentage of advanced Western European and English-speaking democracies have a large gap, suggesting advanced, highly developed democracies have a higher percentage of women with critical democratic expectations (Figure 2).

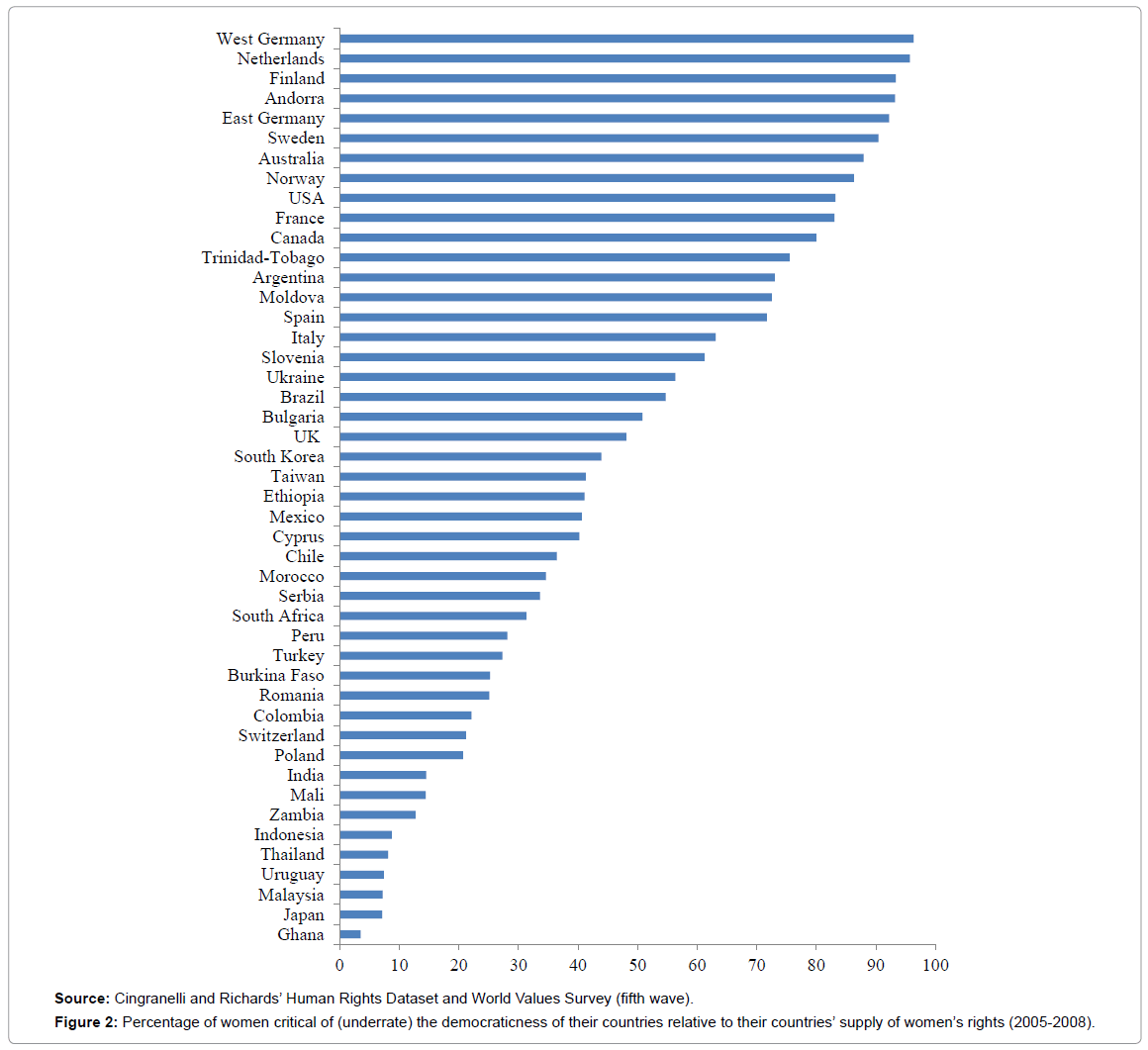

Figure 2 shows us the distribution of countries according to the measurement of women’s critical assessment of democracy used in the following analysis: the percentage of women per country who underrate the democraticness of their democracies relative to the supply of women’s rights. The variation across this sample of democracies is extensive. Again, older, more advanced democracies have the highest percentages and clearly dominate the top half of the distribution.

H1 hypothesizes that the percentage of women who believe that women’s rights are absolutely essential to their countries’ democratic achievement and the percentage of women who participate in elite challenging action are significant predictors of the cross-national variation in the percentage of women that critically assess their democracies. Across the sample of democracies, both variables are significant correlates of critical assessment and, as hypothesized, their combined measure is a stronger correlate than each taken separately. The combined measure correlates with critical assessment at 0.65 (Table 1).

| DV: % of Women with Critical Democratic Expectations (Mid-2000s) | ||

|---|---|---|

| IVs | Unstandardized Betas | Standardized Betas |

| Constant | 0.07 (0.20) | - |

| % Women ECA+% Women Strongly Believe Women’s Rights Essential (Mid-2000s) | 1.27* (2.62) | 0.45 |

| % of Women Highly Interested in Politics and Vote (Mid-2000s) | -0.63 (-0.62) | -0.10 |

| Level of Human Development (Mid-2000s) | 0.73* (2.16) | 0.45 |

| % Protestants (Mid-2000s) | 0.33 (1.70) | 0.28 |

| Level of Democracy (Mid-2000s) | -0.47 (-1.08) | -0.24 |

| Level of Global Political Linkage (Mid-2000s) | -0.00 (-0.90) | -0.13 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.45*** | |

| N | 44 | |

Note: Entries are unstandardized and standardized regression coefficients based on Ordinary Least Squares regression analysis. T-ratios are in parentheses. ***p ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05.

Table 1: Country level predictors of women’s critical democratic expectations.

The relationship holds when the rival variable and the control variables are added as potential predictors under Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis. According to the results of this analysis, just two variables are significant predictors of the percentage of women with critical assessments of democracy: the influence hypothesized in H1, percentage of women who believe women’s rights are essential to democracy combined with the percentage of women who engage in elite challenging behavior, and countries’ level of human development. Both variables are positive. Overall, the model performs moderately well with an adjusted R2 of 0.45. Thus, the results are consistent with H1. This evidence suggests that the higher the percentage of women who give the highest importance to women’s rights as an essential characteristic of democracy and engage in elite-challenging behavior, the higher the level of women’s critical assessment of their democracies per country.

H1M hypothesizes that women who give highest importance to women’s rights and engage in elite-challenging behavior are more likely to critically assess their democracies and that this relationship is stronger in countries where women’s critical assessment is more widespread (Table 2).

| Dependent Variable: Level of Critical Democratic Expectations per Respondent | ||

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -0.35*** (-5.47) | |

| Country-Level Effects | ||

| Percent Critical | 0.59*** (16.08) | |

| Human Development | .16* (2.37) | |

| Political Globalization | -0.02 (-0.49) | |

| Percent Protestants | -0.07* (-2.05) | |

| Democracy | 0.00 (0.03) | |

| Individual-level Effects | ||

| ECA+Women’s Rights Essential | 0.33** (2.93) | |

| University Education | -0.01 (0.79) | |

| Employed | 0.00 (0.66) | |

| Age, Years | -0.00 (-1.12) | |

| Highly Interested Voter | -0.02 (-2.05)* | |

| Cross-Level Interactions | ||

| Percent Critical *ECA_WomRights | 0.20** (3.35) | |

| Human Dev * ECA_WomRights | -0.09 (-0.57) | |

| Pol Glob * ECA_WomRights | -0.05 (-0.37) | |

| Per Protestants * ECA_WomRights | -0.12 (-1.45) | |

| Democracy * ECA_WomRights | -0.39* (-2.10) | |

| N | 23, 196 individuals in 39 countries | |

| Within society variation of DV (level-1) | 1 percent | |

| Between society variation of DV (level-2) | 92 percent | |

| Variation in Effect of ECA_WomRights | 35 percent | |

Note: Entries are unstandardized regression coefficients based on robust standard errors, with T-ratios in parentheses. Individual-level variables are country-mean centered. Country-level variables are global-mean centered. Explained variances calculated from change in random variance component related to ‘null model.’ Significance levels: l p?0.10 *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Analyses conducted with HLM 6.08.

Table 2: Cross-level predictors of women’s critical democratic expectations.

Table 2 reports the results from multilevel analysis run with HLM 7.0. As the results show, the variable at the individual-level measuring importance attributed to women’s rights combined with level of engagement in elite challenging behavior (critical mobilization) is positive and significant. This is consistent with one of the expectations posited under H1M. In addition, the cross-level interaction with the country-level measure of the percentage of women that underrate the democraticness of their countries relative to the supply of women’s rights (critical assessment) is also positive and significant. Consistent with the second expectation of H1M, this result suggests that the relationship between critical mobilization and critical assessment among individuals is stronger when they are embedded in a country where critical assessment is more widespread among women.

We want to make it clear at this point that while the literature posits a relationship running from the critical mobilization of women to women’s likelihood to critically assess their democracies, in the analysis and results presented here, we are given no evidence for determining causal direction. The opposite direction that, for instance, critical assessment leads to critical mobilization is also plausible. Probably, the most likely interrelationship between these variables is virtuously, mutually reinforcing. Thus, the takeaway here is that female critical mobilization and female critical assessment are linked. In moving forward, we take the variable that is theoretically supported as more causally proximate in links in the chain that potentially impact democracies’ supply of gender equality, critical assessment, and evaluate the relationship between this and a widely used measure of gender inequality under relevant controls.

Taking this step, H2 hypothesizes that the higher the level of women’s critical assessment of their democracies the lower the level of gender inequality in their democracies. Table 3 presents the results of the multivariate analysis. H2 is confirmed. The percentage of women with critical democratic expectations is a significant, negative predictor of countries’ level of gender inequality. Two additional variables are also significantly, negatively related to countries’ level of gender inequality: countries’ level of development and state capacity. With an adjusted R2 of 0.83 the model performs very well (Table 3).

| DV: Gender Inequality Index (Late 2000s) | ||

|---|---|---|

| IVs | Unstandardized Betas | Standardized Betas |

| Constant | 0.96*** (4.62) | - |

| % Women Critical Democrats (Mid-2000s) | -0.13* (-2.09) | -0.21 |

| % of Women Highly Interested in Politics and Vote (Mid-2000s) | 0.05 (0.13) | 0.01 |

| Level of Human Development | -0.51** (-3.09) | -0.42 |

| % Protestants (Mid-2000s) | 0.14 (1.89) | 0.19 |

| Level of Democracy (Mid-2000s) | -0.19 (-1.10) | -0.13 |

| State Capacity (Mid-2000s) | -0.09* (-2.67) | -0.45 |

| Level of Global Political Linkage (Mid-2000s) | 0.00 (1.31) | 0.11 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.83*** | |

| N | 44 | |

Note: Entries are unstandardized and standardized regression coefficients based on Ordinary Least Squares regression analysis. T-ratios are in parentheses. ***p ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05.

Table 3: Country Level Predictors of the Gender Inequality Indexes.

To wrap up the results section, in all the models in which the variables are included, the rival explanations to H1 and H2, the extent to which women are engaged voters in their countries does not impact the outcome variables of interest. This finding speaks to larger assessments in the literature that find formal channels of democratic influence deeply male dominant and path dependent. This dominance and path dependency make it especially difficult for relatively new interests, such as gender equality, to make it onto the political agenda through formal electoral channels. From a short term perspective, these results offer gender equality advocates a strategy as concerns maximizing the impact of female mobilization campaigns. These actors should target civil society and social movement mobilization rather than voting behavior. From a long term perspective, the inability of engaged female electoral engagement to translate into gender equality outcomes is a fundamental problem for democracy and needs more research.

Conclusion

A large body of case-study research tells us that democratic transitions improve gender equality when a higher level of women participate in the critical civil movements that support the transition, and women believe that the protection of women’s rights is absolutely essential to the development of democracy in their countries. This mobilizes a higher level of critical democratic assessment and expectations among women which increases what women demand of their new democracies in the treatment of gender inequality. The larger literature on democratization and citizens’ democratic expectations tells us that this process should generalize to democracies at all stages of the democratization process, including the most advanced democracies. So far, however, this has not been demonstrated through systematic, cross-national analysis.

This study builds on that gap and looks at the relationships between female critical mobilization, female critical assessment and democracies’ treatment of gender inequality with data from a large, diverse set of democracies. Two key findings emerge from the analysis:

1) In democracies where women see women’s rights as absolutely essential to democratic achievements and elite-challenging action is high among women, women are more critical of the ‘democraticness’ of their countries relative to their countries’ supply of women’s rights.

2) Gender inequality is lower in democracies where the level of women who are critical of their democracies is higher.

In this case, the study lends evidence to the links between female critical mobilization, female critical assessment and democracies’ treatment of gender inequality. It also suggests that greater insights into how democracies more effectively treat gender inequality will be achieved through research focused on women’s understanding of their rights as democratic rights, the importance they attribute to democratic institutions as mechanisms for improving gender inequality, the extent to which they support global and local activism on behalf of women’s rights as part of a larger democratization frame and the effectiveness with which they use democratic institutions to improve gender inequality within their nations.

Comparative public opinion research is an obvious empirical strategy for collecting this data. However, existing comparative public opinion projects are severely limited in the questions they ask with respect to these larger research aims. The majority of current global survey projects include just a few gender related batteries and none focus exclusively on women’s understanding and support for democracy and their motivations and strategies for using democratic ideals and institutions to reduce gender inequality.

1Similar points have been made by leading feminist theorists (see for example Pateman [15]; Young [18], Phillips [19]).

2Alexander and Welzel [38] find that increasing general activity in social movements leads to more critical values orientations that, in turn, positively impact both women’s political and socioeconomic rights. The study does not, however, look at the impact of women’s social movement activity in particular.

3Cingranelli-Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Data Project [46] includes three measures of women’s rights that are combined into the overall women’s rights score per country: “Women’s Political Rights Index,” “Women’s Economic Rights Index,” and “Women’s Social Rights Index.” The “Political Rights Index” includes information on the right to vote; the right to run for political office; the right hold elected and appointed government positions; the right to join political parties; and the right to petition government officials. CIRI’s “Economic Rights Index” includes information on countries’ adoption and enforcement of equal pay for equal work; free choice of profession or employment without the need to obtain a husband’s or male relative’s consent; equality in hiring and promotion practices; equality in job security (maternity leave, unemployment benefits, etc.); non-discrimination by employers; right to be free from sexual harassment; right to work at night; right to work in occupations classified as dangerous; and right to work in the military or police force. CIRI’s “Social Rights Index” includes information on the right to equal inheritance; right to enter into marriage on the basis of equality with men; the right to travel abroad; the right to obtain a passport; the right to confer citizenship to children or a husband; the right to initiate divorce; the right to own, manage, and retain property brought into marriage; the right to participate in social, cultural and community activities; the right to an education; the freedom to choose a residence/ domicile; freedom from genital mutilation of children and of adults without their consent; and freedom from forced sterilization.

References

- Bystydzienski J, Sekhon J (1999) Democratization and Women’s Grassroots Movements. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Okeke-Ihejirika P, Franceschet S (2002) Democratization and State Feminism: Gender Politics in Africa and Latin America. Development and Change 33: 439-466.

- Viterna J, Fallon K (2008) Democratization, Women’s Movements and Gender-Equitable States: A Framework for Comparison. American Sociological Review 73: 668.

- Waylen G (1994) Women and Democratization: Conceptualizing Gender Relations in Transition Politics. World Politics 46: 327-354.

- Goetz AM, Hassim S (2002) In and against the party: Women’s representation and constituency building in Uganda and South Africa. Gender, justice, development and rights Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp: 306-343.

- Inglehart R, Welzel C (2005) Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge University Press, p: 333.

- Hassim S (2002) A Conspiracy of Women: The Women’s Movement in South Africa’s Transition to Democracy. Social Research 69: 693-732.

- Bouvier V (2009) Crossing the Lines: Women’s Social Mobilization in Latin America. In: Goertz A (ed.) Governing Women, New York: Routledg, pp: 25-44.

- Safa H (1990) Women’s Social Movements in Latin America. Gender and Society 4: 354-369.

- Noonan RK (1995) Women against the state: Political opportunities and collective action frames in Chile's transition to democracy. Sociological Forum 10: 81-111.

- Einhorn B (1993) Cinderella Goes to Market: Citizenship, Gender and Women’s Movements in East Central Europe.London: Verso.

- Fodor E (2009) Women and Political Engagement in East Central Europe. Governing Women: Women's Political Effectiveness in Contexts of Democratization and Governance Reform. London: Routledge, p: 17.

- Pateman C (1988) The Sexual Contract. Stanford University Press, p: 276.

- Paxton P (2000) Women’s Suffrage in the Measurement of Democracy: Problems of Operationalization. Studies in Comparative International Development35: 92-111.

- Paxton P (2009) Gender and Democratization. In: Haerpfer, Bernhagen, Inglehart, Welzel. Democratization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Young I (1990) Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Phillips A (1991) Engendering Democracy.Cambridge University Press, p: 183.

- Alexander AC, Coffé H (2018) Women’s Political Empowerment through Public Opinion

- Bourque S, Grossholtz J (1998) Politics an unnatural practice: Political science looks at female participation. Feminism and politics 23-43.

- Sarvasy W, Siim B (1994) Gender, transitions to democracy, and citizenship. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 1: 249-255.

- Siim B (2000) Gender and citizenship: Politics and agency in France, Britain and Denmark. Cambridge University Press, p: 220.

- Coffé H, Bolzendahl C (2010) Same game, different rules? Gender differences in political participation. Sex roles 62: 318-333.

- Harrison L, Munn J (2007) Gendered (non) participants? What constructions of citizenship tell us about democratic governance in the twenty-first century. Parliamentary Affairs 60: 426-436.

- Banaszak LA (2006) Women’s movements and women in movements: Influencing American democracy from the outside. 79-95.

- Beckwith K (2013) The comparative study of women’s movements. The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics, pp: 385-410.

- Goetz AM (2009) Governing Women: Women’s Political Effectiveness in Contexts of Democratization and Governance Reform. New York: Routledge, p: 318.

- Inglehart R, Norris P (2003) Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World. Cambridge University Press.

- Dalton R (2008) Citizenship Norms and the Expansion of Political Participation. Political Studies56: 76-98.

- Dalton R (2006) The Two Faces of Citizenship. Democracy and Society 3: 21-29.

- Norris P (2002) Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism. Cambridge University Press.

- Klingemann HD, Fuchs D (1999) Citizens and the State. Oxford University Press.

- Nevitte N (1996) The Decline of Deference. Peterborough: Broadview Press

- Inglehart R, Welzel C (2005) Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge University Press, p: 333.

- Alexander AC, Welzel C (2015) Eroding Patriarchy: The Co-Evolution of Women’s Rights and Emancipative Values. International Review of Sociology 25: 144-165.

- Franzmann M (2000) Women and Religion. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Alexander AC, Welzel C (2011) Empowering Women: The Role of Emancipative Beliefs. European Sociological Review27: 364-384.

- Alexander AC, Welzel C (2011) How Robust is Muslim Support for Patriarchal Values? A Cross National, Multilevel Study. International Review of Sociology21: 249-276.

- Berkovitch N (1999) From Motherhood to Citizenship: Women’s Rights and International Organizations. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Keck M, Sikkink K (1998) Activists Beyond Borders. Cornell University Press, New York.

- Paxton P, Hughes M (2007) Women, Politics and Power: A Global Perspective. Los Angeles: Pine Forge Press, p: 520.

- Alexander AC, Bolzendahl C, Jalalzai F (2017) Introduction to Women’s Political Empowerment across the Globe: Strategies, Challenges and Future research. Palgrave.

- Alexander AC, Welzel C (2011) Measuring Effective Democracy: The Human Empowerment Approach.Comparative Politics 43: 271-289.

- Atkeson LR (2003) Not All Cues are Created Equal: The Conditional Impact of Female Candidates on Political Engagement. The Journal of Politics 65: 1040-1061.

- McBride D, Mazur A (2008) Women’s Movements, Feminism, and Feminist Movements. (edn), Cambridge University Press, pp: 219-243.

- Norris P, Krook M (2009) One of Us: Multilevel Models Examining the Impact of Descriptive Representation on Civic Engagement.

- O’Regan V (2000) Gender Matters: Female Policymakers’ Influence in Industrialized Nations.

- Raudenbush S (2004) HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software International, p: 297.

Citation: Alexander AC (2018) Women’s Critical Mobilization, Critical Assessment of their Democracies and the Treatment of Gender Inequality in their Democracies. J Civil Legal Sci 7: 241. DOI: 10.4172/2169-0170.1000241

Copyright: © 2018 Alexander AC. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4761

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Nov 14, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3860

- PDF downloads: 901