What the Tweets Say: Understanding the Connectivity between Health Development Agencies

Received: 28-Jun-2019 / Accepted Date: 12-Aug-2019 / Published Date: 21-Aug-2019

Abstract

The primary goal of this work was to determine how seven major development, agencies are engaging with users on Twitter. The sample included 11,441 Twitter users that seven development agencies were following in December 2018. We used Social Network Analysis (SNA) to analyze connectivity, interaction, and influence. Out of the 11,441 users followed by donors a fifth of the users are followed by more than one donor indicating that these 2,272 users could have been purposefully selected based on their influence in global health or more broadly development. In addition, major development agencies are following different user accounts. In comparing the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Nations they follow different accounts about 98% of the time. When using Twitter for information it is important for policymakers to consider multiple Twitter feeds for information. A limited online perspective could shape policy discussions-even if it isn’t recognized as the primary source of information by leaving the impression that the reader has a broader understanding of the online content than is true.

Keywords: Twitter communication; International development; Social network analysis

Introduction

Americans are increasingly turning to the internet for information on government and politics. What began as a simple means to stay connected with friends and family has become a powerful source of information. In fact, approximately two-thirds of U.S. adults who use Twitter get news on the platform [1], and this use is not restricted to individuals. Government agencies are engaging with social media as a mechanism to improve the quality of services [2]. While this demonstrates an efficient way to gain –policy knowledge there are inherent flaws to relying on social media as a primary source for information due to the rapid dissemination of misinformation [3], and the ability of inaccurate or false information to spread at a tremendous rate [4]. Misinformation can cascade into more extreme versions over time [5] making it difficult to identify false information from real information. A recent survey shows only about 44% of users say they feel able to tell a false news story from a real one [6]. Therefore, it is important to develop a better understanding of these technologies and their impact on communication [7], as there is currently a lack of information about the uses, benefits, and limitations of such communication [8].

Social media has led news publishers to lose control over distribution of their information [9], so there are several things that should be considered before using policy information discovered on social media sites. First, the author and audience of the information is important to consider because often information is presented in a way that can sway a reader’s opinion on important issues. Of particular concern is astroturfing which creates an impression of widespread support for a policy when in fact little support exists [10]. This is often times achieved when nonprofit advocacy organizations are using social media to persuade people of their point of view [11]. Second, the connectedness between organizations that share information on social media is important. Often the same information is repeated by different organizations, which can lead users to become fixed on one view; thinking that it is the only view since the same message is reinforced numerous times. This is the issue of the “collective opinion”, in which people often times are more inclined to believe something because the majority is already agreeing to it [12]. Third, it is important to consider the target audience of these sources, because there are times when organizations are connected to the same user base, in order to achieve a common goal. Considering the influence of social media and the potential concerns of the reliability of the information; it is important that policymakers carefully consider the influence that social media may have on shaping policy discussionseven if the social media isn’t recognized as the primary source of information in the formation of new policies.

Of particular importance is a better understanding of how Twitter, a web-based micro blogging service that allows registered users to send short update messages to others, is being [13] used for news and not just any news-the news from seven major we major development agencies that share a common goal of improving health for people in low and middle income countries. As the global health community works towards a shared blueprint for development, outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), major development agencies are searching for more effective and efficient ways to deliver development assistance [14]. Interaction through an online social network, such as Twitter, potentially results in the exchange of prevailing ideas about development assistance and therefore shapes a dialogue about global health.

The primary goal of this work was to determine how seven major developments are engaging with users on Twitter. Under the assumption that a small number of major development agencies serve as the center of the Development Assistance for Health (DAH) networks on social media, we investigated the connections to the users they are following. We approached this question through exploratory research leveraging the openness of social media.

Methods

In order to better understand how major development agencies are engaging with users on Twitter, we built a sample of seven major development agencies using data obtained from the Twitter API. The agencies were selected based on their involvement with the management of DAH, the mechanisms to channel DAH to recipients, or their role in shaping polices related to DAH. The network included the United Nations (UN), World Health Organization (WHO), The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, The Global Fund, World Bank Group, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and The Department for International Development (DFID). The sample included 11,441 users that these seven development agencies were following in December 2018.

We used Social Network Analysis (SNA) to graph the relationships that exist between development agencies. Therefore, providing a way of analyzing how the development agencies are connected, how they interact, and who the important influencers are in a network.

Results

Agencies as sources of information

When analyzing agencies as a source of information results indicate that the agencies following the largest number of users are the Global Fund and DFID (following 3,752 and 2,543 respectively) and the agencies following the smallest number are USAID and World Bank (following 680 and 648 respectively). Twitter users are primarily exposed to the users they actively follow. This indicates that that the Twitter feed from Global Fund and DFID is more diverse in terms of content and therefore has the potential to propagate new ideas.

Ties that bind: Does connectedness matter?

In addition to gaining a better understanding of size, we can also learn something about how users group together, or cluster. Put simply, the users these organizations are following are more likely to know each other than two organizations chosen randomly. In the case of the development agency network, it is highly disconnected with a low clustering coefficient. Indicating that information isn ’ t flowing between agencies through their social media feed.

On average about a third to one-half of all users followed by a major development agency also are followed by at least one other development agency. This is highest at the UN and WHO were fortyeight percent of the users the UN follows also are followed by another agency. Conversely, at the World Bank 3% of all users are also followed by at least one other development agency. In fact, out of the 11,441 users followed by donors a fifth of the users are followed by more than one donor indicating that these 2,272 users could have been purposefully selected based on their influence in global health or more broadly development. Therefore, the information from a small group of people may appear in multiple feeds.

Greatest connectedness to other users within the network

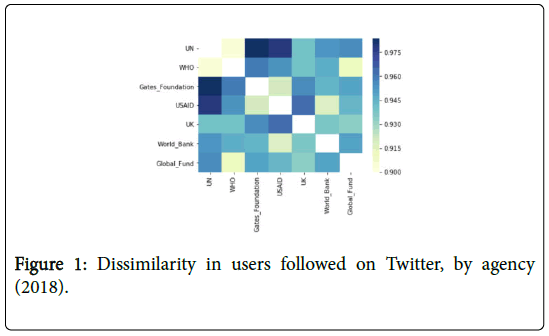

Figure 1 compares the following users for two development agencies to see which users are shared and which users are distinct. The higher the percentage, the higher the differences are in Twitter followers between the two development agencies. As seen in Figure 1, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Nations follow different accounts. The value of .975 means that in comparing the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Nations they follow different accounts about 98% of the time. This indicates that it is unlikely that the content that the United Nations is following is similar to the content the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is following.

Conclusion

Although this descriptive work provided insight into the network of major development agencies there remain several limitations to be discussed. First, due to data limitations we were unable to do an analysis of how the network grows. Furthermore, it was outside of the scope of this work to do a qualitative analysis on tweet content. Finally, the small sample size and descriptive nature of this work limit generalizability of the findings. Despite these known limitations results indicate that shared information in the Twitter network of major development agencies is limited through social media. The analysis indicates that although there is a small number of users that may appear in multiple feeds there is limited connectivity between these development agencies, and the people that these organizations follow on Twitter. When taking into account the information sent out by these organizations, the user connectivity identified becomes extremely relevant in terms of users being exposed to limited policy relevant content if only following one user. When using Twitter for information related to DAH, it is important for policymakers to consider multiple Twitter feeds for information, as not all accounts achieve their desired outcomes [15]. Otherwise the perspective will remain limited leaving the impression that the reader has a broader understanding of the online content than is true. This limited perspective could shape policy discussions-even if it isn’t recognized as the primary source of information.

References

- Shearer E, Gottfried J (2017) News use across social media platforms 2017. Pew Research Center 7: 1.

- Hrdinová J, Helbig N, Peters CS (2010) Designing social media policy for government: Eight essential elements Center for technology in government, university at Albany Albany, New York.

- Del Vicario M, Bessi A, Zollo F, Petroni F, Scala A, et al. (2016) The spreading of misinformation online. PNAS 113: 554-559.

- Figueira A, Oliveira L (2017) The current state of fake news: Challenges and opportunities. Procedia Computer Science 121: 817-825.

- Shin J, Jian L, Driscoll K, Bar F (2018) The diffusion of misinformation on social media: Temporal pattern, message, and source. Comp Human Behav 83: 278-287.

- Robb MB (2017) News and America’s kids: How young people perceive and are impacted by the news. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.

- Chou WS, Hunt YM, Beckjord EB, Moser RP, Hesse BW (2009) Social media use in the united states: Implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res 11: e48.

- Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, Carroll JK, Irwin A, et al. (2013) A new dimension of health care: Systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res 15: e85.

- Bell E (2016) Facebook is eating the world. Columbia Journalism Review 7: 3.

- Conover MD, Ratkiewicz J, Francisco M, Gonçalves B, Menczer F, et al. (2011) Political polarization on twitter. Paper presented at the fifth international AAAI conference on weblogs and social media.

- Auger GA (2013) Fostering democracy through social media: Evaluating diametrically opposed nonprofit advocacy organizations’ use of Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. Pub Relat Rev 39: 369-376.

- Li H, Sakamoto Y (2014) Social impacts in social media: An examination of perceived truthfulness and sharing of information. Comp Human Behav 41: 278-287.

- Honey C, Herring SC (2009) Beyond microblogging: Conversation and collaboration via twitter. Paper presented at the 2009 42nd Hawaii international conference on system sciences 1-10.

- Buse K, Hawkes S (2015) Health in the sustainable development goals: Ready for a paradigm shift?. Globalizat Health 11: 13.

- Korda H, Itani Z (2013) Harnessing social media for health promotion and behavior change. Health Promot Pract 14: 15-23.

Citation: Dolan CB, Shane T, Siebes S (2019) What the Tweets Say: Understanding the Connectivity between Health Development Agencies. J Community Med Health Educ 9:662.

Copyright: © 2019 Dolan CB, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 2310

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Feb 22, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1709

- PDF downloads: 601