Viewpoints of Public Health on the Homecare Difference

Received: 03-Sep-2022 / Manuscript No. jhcpn-22-74284 / Editor assigned: 05-Sep-2022 / PreQC No. jhcpn-22-74284 / Reviewed: 19-Sep-2022 / QC No. jhcpn-22-74284 / Revised: 21-Sep-2022 / Manuscript No. jhcpn-22-74284 / Accepted Date: 27-Sep-2022 / Published Date: 28-Sep-2022 QI No. / jhcpn-22-74284

Abstract

A vital source of care for those with disabilities and chronic illnesses is provided by caregivers. They improve health outcomes among care recipients while incurring unfavourable health repercussions themselves.

Keywords

Population health; Surveillance; Caregiving; Ageing; Disability; Evidence-based interventions are all related to public health

Introduction

However, there is a significant demand for extra caretakers. As a result, providing care is a public health issue. Public health aims to equitably improve the health of populations. This chapter uses the Healthy Brain Initiative: State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia, [1-8] the 2018-2023 Road Map as an example of a public health approach to assisting caregivers of persons with dementia. It outlines 25 ideas for public health action to support caregivers within the framework of fundamental public health services. The Road Map might act as a model for more comprehensively assisting carers. Public health systems must work together to gather data and fairly implement evidence-based policies and programmes that assist those who provide care in their communities in order to address the predicted family care gap.

Case Presentation

The family care gap is the predicted discrepancy between the number of people who will require care or assistance due to chronic diseases or disabilities and the number of family members and friends in the community who are able to give that care, as explained in this chapter. Later parts of this book offer a variety of potential remedies for the family care gap. In this chapter, we [9-11] describe solutions to close the looming family care gap as well as the public health viewpoint on providing care. Following that, we make reference to a lot of the distinct strategies that are covered in other chapters because they are crucial parts of an all-encompassing public health strategy. This chapter examines the connection between caregiving and public health issues and provides a framework for approaching caregiving from this angle. We explore pertinent ageing and disability-related aspects of public health research and practise and how these influence public health initiatives to enhance the health of caregivers and care users. The Healthy Brain Initiative: State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia, the 2018-2023 Road Map, and the Healthy Brain Initiative: The Road Map for Indian Country are examples of how to use a systematic public health approach to [12-14] support caregivers. Next, we offer potential solutions to the family care gap. Finally, utilising the strategies recommended in the Healthy Brain Initiative Road Map series, we provide examples of people and organisations that have actually taken action to enhance the wellbeing and quality of life of carers.

Section I: Caregiving as a public health issue

The public health perspective

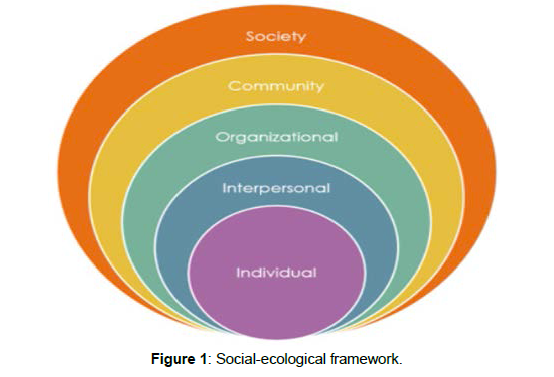

Public health is a broad and diverse profession that focuses on ensuring that all population members benefit from improvements in health and that these improvements are made in an equitable manner (CDC Foundation, n.d.; Institute of Medicine (US), 1988, 2002). Public health initiatives are more particularly aimed at eradicating health disparities, which are potentially avoidable systemic variations in health between groups of people based on a variety of sociodemographic traits or the degree of influence they have within their communities. Leaders in public health not only take into account groups that are more susceptible to health disparities, such as those with low socioeconomic status (SES), women, Hispanics, African Americans, and American Indians and Alaska Natives, but they also employ best practises to try to close the gap between those disparities. The social-ecological framework, which depicts the various levels of influence on health (Figure 1) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is often the foundation for public health initiatives. This paradigm emphasises the interconnection of elements that affect people's health on an individual, interpersonal, organisational, communal, and societal level. The socialecological framework has the implication that efforts focused solely on altering individual behaviours are unlikely to be successful in enhancing population health because these behaviours are only one of a wide range of variables that affect health (such as SES, race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation). Healthcare is sometimes provided by public health, which also supplements treatment received in facilities like hospitals and rehabilitation centres. For instance, many municipal health departments provide dietary assistance and immunizations, and some, such as federally designated health facilities, also offer more complete prenatal and preventive or primary care (Institute of Medicine (US), Institute of Medicine (US). In addition to fighting disease and preventing harm, public health entails ensuring safe settings, access to care and programmes, and the provision of clean air, food, and water. Classifications of public health are frequently wrongly restricted to particular illnesses or health hazards. A public health issue is any circumstance, exposure, occurrence, or experience that has a detrimental effect on the health or quality of life of a population. For older individuals and those with disabilities, carers are a crucial source of community-based care, as this chapter has explained. They provide assistance with a variety of duties, such as grocery shopping, bill paying, getting dressed and bathed, managing medications, and getting around the neighbourhood. Typically, caregivers assist the care recipient's social and medical requirements (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , carers can avoid or delay institutionalisation as well as enhance the health and quality of life of the people they provide care for. Studies have indicated that having an informal (i.e., unpaid) caregiver can help care recipients manage their chronic illnesses better and experience less depressive symptoms, both of which are crucial goals for public health initiatives.

Discussion

Caregiving is seen as a public health concern for a number of reasons, including the beneficial effects that caregivers may have on the health and quality of life of the people they provide care for. The effects of caregiving on one's physical and emotional health are a matter of public health concern. Although they assist in improving their care receivers' health, many caregivers often struggle with their own health issues. Despite the fact that providing care can have numerous advantages, such as a sense of purpose and a stronger bond between the caregiver and the care receiver, research has also shown that the work of a caregiver can be stressful and cause physical, mental, and financial strain. Anxiety and depression are linked to caregiver load, which is brought on by the challenging activities of providing personal care, such as dressing and bathing, or the experience of helping someone with behavioural issues or cognitive impairment. Additionally, when the health of the care receiver deteriorates over time, the demands and responsibilities of the caregiver role may grow, and as a result, the stress on the caregiver's health may increase (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). The social determinants of health, or those aspects of health that are related to where individuals live, work, and play, can have an impact on caregivers in ways that less directly affect their health but are nonetheless relevant (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.-b; World Health Organization, n.d.). Many caregivers cut back on their work hours, switch careers, or give up their professions entirely in order to care for their care receiver. This affects carers' present and future financial well-being as well as their ability to maintain social relationships and engage in society. The cost of providing care can be high, and caregivers may have to pay out of pocket for the care recipient's meals, medical supplies, and other expenses, which would be detrimental to their own financial situation. Because people stay in the community longer rather than entering institutions or obtaining paid home care, much of which would be covered by Medicaid or other programmes, caregivers contribute to annual cost savings of millions of dollars. Some persons who provide care for others become more sedentary, which increases their risk of obesity and linked illnesses like cardiovascular disease. Since over 20% of adults in the US provide care (AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, maintaining the health of caregivers for the sake of caregivers themselves is a public health concern. Additionally, caregivers are at an increased risk of adverse health outcomes as a result of their work their position as caregivers. Caregiving is a public health concern for all of the following reasons: it affects the population's health, including the health of caregivers and care recipients; the effects may not be equally felt by all members of the population; and there are effective prevention strategies that could be used to lessen these adverse effects. According to the Institute of Medicine (US), in 1988, the goal of public health is to "fulfil society's interest in ensuring conditions in which people can be healthy." What can the public health sector do to support those who are providing care and those who are receiving it? Public health has a role in monitoring the number of carers and recording their experiences as well as their health status since, in the first place, public health specialists work to assess the health of populations. In the context of caregiving, this could include educating caregivers about health risks they may be facing, providing them with information about successful programmes to reduce stress or their financial burden, and equipping them with skills to support the care recipient. Second, public health involves informing, educating, and empowering people about health issues (e.g., medical tasks or behaviour management).

Results

Prevention is the main emphasis of public health initiatives to enhance population health. Primary, secondary, and tertiary degrees of prevention are all available.

Conclusion

Primary prevention refers to preventing a disease from occurring, which is what most people think of when they hear the word "prevention." Vaccinating against communicable diseases, keeping lead and other dangerous toxins out of drinking water, and encouraging behaviour modification to reduce the risk of contracting diseases are some examples of primary prevention (e.g., increasing physical activity or quitting smoking).

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to The Regional Center for Mycology and Biotechnology, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Staniforth R., Such E (2019) Public health practitioners' perspectives of migrant health in an English region. Public health 175: 79-86.

- Holroyd TA, Oloko OK, Salmon DA, Omer SB, Limaye RJ, et al. (2020) Communicating recommendations in public health emergencies: The role of public health authorities. Health security 18: 21-28.

- Doherty R, Madigan S, Warrington G, Ellis J (2019) Sleep and nutrition interactions: implications for athletes. Nutrients 11:822.

- Jagannath A, Taylor L, Wakaf Z, Vasudevan SR, Foster RG, et al. (2017) The genetics of circadian rhythms, sleep and health. Hum Mol Genet 26:128-138.

- Somberg J (2009) Health Care Reform. Am J Ther 16: 281-282.

- Wahner-Roedler DL, Knuth P, Juchems RH (1997) The German health-care system. Mayo Clin Proc72: 1061-1068.

- Nally MC (2009) Healing health care.J Clin Invest119: 1-10.

- Weinstein JN (2016) An “industrial revolution” in health care: the data tell us the time has come.Spine41: 1-2.

- Marshall EC (1989) Assurance of quality vision care in alternative health care delivery systems. J Am Optom Assoc 60: 827-831.

- Sohn M (2012) Public health law and ethics. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 24:850-850.

- Adithyan GS, Sundararaman T (2021) Good public health logistics for resilient health systems during the pandemic: Lessons from Tamil Nadu. Indian J Med Ethics: 1-10.

- Colin C (2004) Public health in Quebec at the dawn of the 21st century. Sante Publique 16: 185-195.

- Leeder SR (2004) Ethics and public health. Internal medicine journal 34: 435-439.

- Gitau-Mburu D (2008) Should public health be exempt from ethical regulations? Intricacies of research versus activity. East African Journal of Public Health 5:160-162.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Guiro L (2022) Viewpoints of Public Health on the Homecare Difference. J Health Care Prev, 5: 174.

Copyright: © 2022 Guiro L. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 1625

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Apr 02, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1295

- PDF downloads: 330