Utility of a Novel Model of Genomic Deletion of 6-Phosphofructo-2- Kinase/Fructose-2,6-Bisphosphatase (PFKFB3) in Developing Effective Anti-Cancer Strategies

Received: 15-Oct-2024 / Manuscript No. AOT-24-150116 / Editor assigned: 17-Oct-2024 / PreQC No. AOT-24-150116 (PQ) / Reviewed: 30-Oct-2024 / QC No. AOT-24-150116 / Revised: 06-Nov-2024 / Manuscript No. AOT-24-150116 (R) / Published Date: 13-Nov-2024 DOI: 10.4172/aot-1000295

Abstract

A metabolic shift to a high rate of glycolysis is frequently observed in tumors and provides critical biosynthetic intermediates and energy for their rapid growth. The 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatases (PFKFB1-4) have been recognized as important regulators of glycolysis due to their production of fructose-2,6- bisphosphate (F26BP) which activates a rate-limiting, key glycolytic enzyme, 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase enzyme (PFK-1). Due to its high kinase activity and resultant contribution to the concentration of F26BP, the PFKFB3 isoform has been extensively interrogated and determined to play a prominent role in tumor glycolysis and growth, thereby validating it as a viable target for the development of novel inhibitors. To fully understand the function of PFKFB3 and effects of decreasing its expression, the generation and examination of a model of effective genomic PFKFB3 deletion has been a critical development. Studies conducted with this recently developed inducible model of pantissue homozygous PFKFB3 genomic deletion have demonstrated the importance of the PFKFB3 enzyme in tumor growth. Additionally, the studies detailing the examination of this model have also served to validate the on-target effects of recently developed novel antagonists of PFKFB3 and indicate important avenues for developing new strategies for the effective treatment of cancer.

Keywords: Glycolysis; Mouse model; Genomic deletion; PFKFB; PFKFB3; Cancer; Cancer therapeutics

Introduction

Metabolic reprogramming with a resultant increase in reliance on glycolysis are widely recognized as key hallmarks of cancer [1]. The examination of the glycolytic pathway and its regulation are therefore critical for understanding their contribution to cancer growth. The bi- functional PFKFB family of enzymes (PFKFB1-4) plays an important role in glycolytic regulation due to their production of a potent activator of glycolysis termed F26BP [2,3]. Of these enzymes, PFKFB3 has been extensively examined and found to be a valid target against which therapeutics are currently being examined [4,5]. The recent development of an inducible model of PFKFB3 genomic deletion has allowed the detailed examination of the role of PFKFB3 in vivo and effects of its deletion on cancer growth [6]. The goal of this paper is to highlight the importance of this model and these data in validating effects of small molecule inhibitors of the PFKFB3 enzyme and for the future development of novel anti-tumor therapeutic strategies.

Materials and Methods

Glycolysis and regulation by the PFKFB family of enzymes

Glucose metabolism plays a critical role in supporting tumor growth and expansion due to its ability to supply biosynthetic precursors and energy essential for their rapid proliferation [7]. A high rate of glycolytic metabolism is found in multiple tumor types and, additionally, has been widely demonstrated even in the presence of oxygen (i.e. aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect) [7].

Due to the recognition of the crucial role played by glycolysis in supporting the growth and progression of many cancers, effectors whereby the glycolytic pathway is regulated are under significant scrutiny. Of these effectors, the PFKFB enzymes have been demonstrated to play an important regulatory role in glycolysis due to their production of F26BP. F26BP is the most potent activator of the PFK-1 enzyme which performs a critical, rate-limiting function in the glycolytic pathway by catalyzing the first committed step, the conversion of fructose-6- phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate [2,3]. The 4 PFKFBs have differing kinase:bisphosphatase (K:B) ratios and, as a result, varying contributions to the intracellular concentration of F26BP. Of these enzymes, PFKFB3 has the highest kinase activity (with a K:B ratio of ~740:1) and therefore is considered to contribute significantly to F26BP production and the regulation of the rate of glycolysis [8,9].

The PFKFB3 enzyme in cancer

As a result of its high kinase activity and consequent F26BP production and its potentially critical function in the regulation of glycolysis, the PFKFB3 enzyme has been extensively interrogated in cancer. PFKFB3 was first identified as an isoform of 6-phosphofructo- 2-kinase found to be induced by proinflammatory stimuli and constitutively expressed in several human cancer cell lines [8]. Since its initial description, high PFKFB3 (mRNA and protein) expression has been reported in numerous solid and hematogenous tumor types [10]. PFKFB3 expression is also strongly activated or promoted by a number of stimulatory molecules and factors including hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), estradiol and synthetic progestins which play key roles in tumor development and therefore underscore the importance of PFKFB3’s role in the glucose metabolism of tumors and their rapid proliferation and growth [6]. An additional and more recently elucidated mechanism whereby PFKFB3 expression and activity are increased is through the loss of the Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog (PTEN) tumor suppressor which results in a decrease in the degradation of PFKFB3 by Anaphase Promoting Complex/cdc20 homolog 1 (APC/Cdh1) [11]. Interestingly, in tandem with the role of F26BP derived from PFKFB3 in the regulation of glycolysis at the PFK-1 enzyme, F26BP has also been ascribed a function in cell proliferation through the activation of the cyclin-dependent kinases [12]. To further evaluate the importance of PFKFB3 in tumor glycolysis and proliferation, studies have examined the effects of decreasing its expression in oncogene-driven cancer cells and tumor growth and have determined that decreasing PFKFB3 expression decreased glycolysis and cell proliferation [13,14]. These preliminary data have validated PFKFB3 as a potentially important target in cancer and led to the development of small molecule antagonists of PFKFB3 that are under preclinical and clinical evaluation [4,5].

Results and Discussion

Examination of an inducible model of Pfkfb3 deletion

Based on the ongoing interrogation of PFKFB3 inhibitors as promising potential cancer therapeutics, studies that serve to verify the on-target effects of these agents and address concerns regarding their safety with systemic administration have significant clinical import. To that end, the development and interrogation of a pan-tissue model of homozygous PFKFB3 deletion are critical as this model would serve to fully define the global effects of PFKFB3 expression and also delineate consequences of inhibiting its expression and activity in vivo. In previous studies, our laboratory created a constitutive model of homozygous PFKFB3 deletion [15]. This model demonstrated that PFKFB3-driven glycolysis is required for embryonic and organ development however, as a result of the critical requirement for PFKFB3 in embryogenesis, our experiments failed to generate homozygous knockouts thus precluding an examination of the effects of PFKFB3 deletion in adult tissues and organs. The recent development and description of a novel, inducible model of homozygous pan-tissue PFKFB3 deletion has, for the first time, permitted an accurate assessment of these effects [6].

The first studies conducted with this novel inducible model of PFKFB3 deletion (tamoxifen, TAM-inducible Cre-bearing Pfkfb3fl/fl or Cre/Pfkfb3fl/fl mice) examined the efficacy of recombination and found resultant widespread effective PFKFB3 genomic deletion in all evaluated organs indicated by decreased PFKFB3 protein expression and F26BP. Importantly, we determined that homozygous genomic deletion of PFKFB3 did not have deleterious effects on the histology or function of vital organs examined which may in part be the result of the known co-expression of several PFKFB isoforms in the majority of organs contributing to their F26BP production [6]. PFKFB3 deletion also did not affect body mass or life span or cause any signs of distress which carry great significance for the successful development of PFKFB3 antagonists for clinical application [6].

Effects of PFKFB3 genomic deletion on tumor growth

Based on the known reliance of tumor proliferation and growth on glycolytic metabolism, the studies that were used to validate this genomic deletion model were targeted at determining the effect of decreased PFKFB3 expression on the growth of oncogene-driven spontaneous tumor models selected for their relevance and similarity to human cancers. The first tumor model evaluated was a HER2- driven spontaneous mammary adenocarcinoma model (Erbb2 mice) [16] where we elected to examine the effect of PFKFB3 deletion on established tumors with the goal of simulating a possible scenario wherein therapeutic intervention with an PFKFB3 antagonist may be considered in a patient with cancer. Our experiments found that genomic deletion of PFKFB3 and the subsequently decreased PFKFB3 expression led to a significant reduction in tumor glucose uptake measured by 18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose uptake by Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan, and to a decrease in intra-tumoral F26BP concentrations and tumor growth suggesting the potential utility of an inhibitor of glycolysis as an anti-neoplastic agent. Our studies also examined a second model of cancer with high clinical relevance, a lung tumor model closely resembling human lung cancer with spontaneous and gradual development of adenomas and adenocarcinomas due to activation of a latent K-ras oncogene (K-rasLA1 mice) [17]. We found that PFKFB3 genomic deletion decreased both tumor initiation and growth in this model. Taken together, the efficacy of PFKFB3 deletion and resultant decrease in PFKFB3 expression and activity provided confirmation of the on-target effects of PFKFB3-selective inhibitors and, more importantly, provided promising preliminary evidence of the potential efficacy of PFKFB3 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for cancer. Since these studies also established the effectiveness of recombination and genomic deletion in our model, they have now paved the way for further examination of the effects of PFKFB3 deletion in other relevant cancer models and in the evaluation of the effects of its deletion on the tumor microenvironment which will widen the scope of application of PFKFB3 inhibitors and enhance our understanding of the effects of these agents.

Although our examination of the effects of homozygous PFKFB3 deletion on tumor growth found that it substantially decreased growth in both models, we observed greater growth inhibition in the Erbb2 model than the K-rasLA1 lung cancer model and, similarly, greater effects on cell cycle progression and proliferation in the Erbb2 model relative to the K-rasLA1 model. We speculate that the differences in responses of the model systems were likely related to differences in their timing of induction of PFKFB3 genomic deletion. In the HER2-driven mammary tumor model, we induced PFKFB3 deletion after palpable tumors were noted, to mimic the situation wherein a PFKFB3 antagonist might be administered to a patient. Additionally, since the mammary tumors in this model demonstrate aggressive growth after initial appearance, the control tumors rapidly reached endpoint so the experimental time period following induction of PFKFB3 deletion was relatively short (~3 weeks). In contrast, tumor growth in the K-rasLA1 lung cancer model is more gradual with early surface nodules and tumors noted at 10-17 weeks that reach larger and clinically significant volumes by approximately 32 weeks [18]. Additionally, since an important objective of assessing this model of gradual tumor growth was to determine effects of PFKFB3 deletion on tumor initiation, deletion was induced at 6 weeks of age (prior to the noted onset of early nodules) and mice were followed for an additional 26-28 weeks until signs of distress were noted in control animals. We hypothesized that the prolonged period of decreased PFKFB3 expression in this model might have led to the utilization of alternate pathways to support growth. Based on the previously demonstrated co-expression of other PFKFB isoforms along with PFKFB3 in lung and several other cancer types, we speculated that another PFKFB enzyme might have compensated for the loss of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis to support cell cycle progression and tumor growth in this model.

New studies and indications for novel anti-cancer therapeutic strategies

Studies from our laboratory and several others have consistently found evidence of high expression of the PFKFB4 enzyme in addition to its frequent co-expression with PFKFB3 in many tumor types [5,19]. Our studies also have found in vitro evidence of increased PFKFB4 expression when PFKFB3 expression was decreased [19]. PFKFB4 additionally has a high kinase activity (with a K:B ratio of ~4.3:1, in contrast to PFKFB2 with a K:B ratio of ~1.8:1 and to PFKFB1 with a K:B ratio ~1:1 [19,20]) and therefore contributes significantly to intracellular F26BP concentrations.

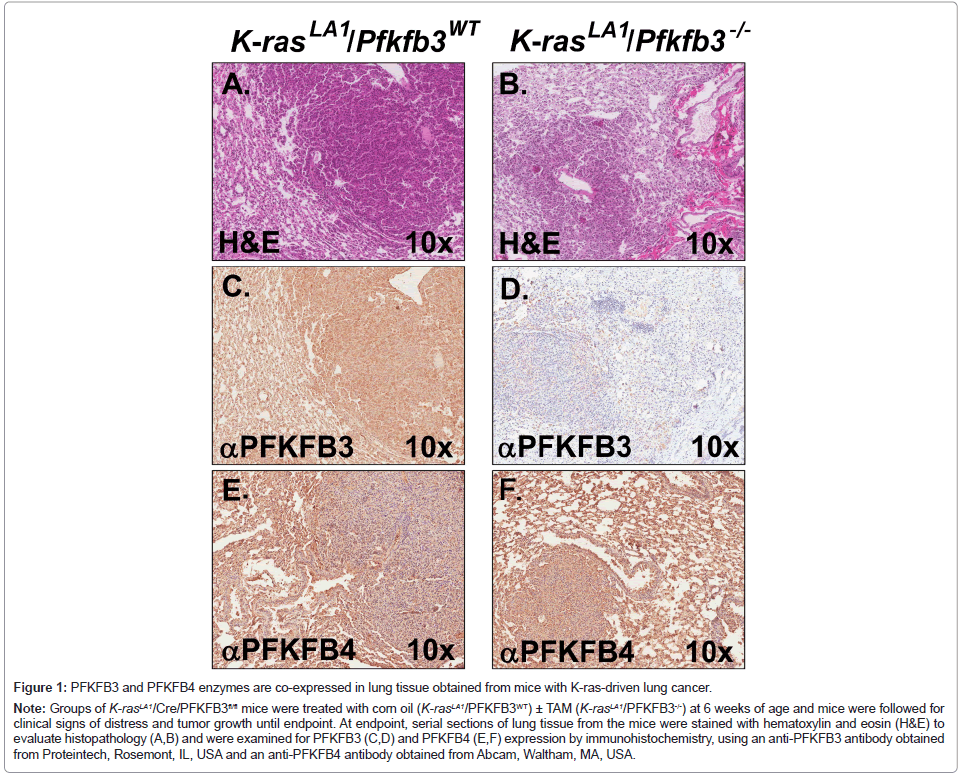

We hypothesized that PFKFB4-derived F26BP might support the growth of lung tumors in the slow-growing K-rasLA1 model. In new studies, we examined serial lung sections from tumor-bearing control (PFKFB3 WT) and PFKFB3-deleted (PFKFB3-/-) K-rasLA1 mice by immunohistochemistry for PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 (Figure 1). We found that PFKFB4 was strongly expressed in control mice (with WT PFKFB3 expression) as expected, but also was highly expressed in PFKFB3- deleted mice where PFKFB3 expression was significantly decreased (Figure 1). We therefore speculate that PFKFB4-driven F26BP likely compensates for the loss of PFKFB3 and is able to support glycolysis, cell cycle progression and tumor growth in this model.

Figure 1: PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 enzymes are co-expressed in lung tissue obtained from mice with K-ras-driven lung cancer.

Note: Groups of K-rasLA1/Cre/PFKFB3fl/fl mice were treated with corn oil (K-rasLA1/PFKFB3WT) ± TAM (K-rasLA1/PFKFB3-/-) at 6 weeks of age and mice were followed for clinical signs of distress and tumor growth until endpoint. At endpoint, serial sections of lung tissue from the mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to evaluate histopathology (A,B) and were examined for PFKFB3 (C,D) and PFKFB4 (E,F) expression by immunohistochemistry, using an anti-PFKFB3 antibody obtained from Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA and an anti-PFKFB4 antibody obtained from Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA.

The possible compensation by PFKFB4 for PFKFB3 deletion is of immediate and significant clinical relevance to the currently ongoing development of small molecule PFKFB3 inhibitors since the anti-tumor efficacy of these agents may be diminished due to the activity of the PFKFB4 enzyme. Taken further, these data suggest that simultaneous inhibition of the PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 enzymes may prove to be a highly effective therapeutic strategy against lung cancer and multiple other tumor types where co-expression of these enzymes is observed. We are currently interrogating effects of simultaneous genomic deletion of both enzymes in vivo and of co-targeting both enzymes with novel inhibitors on tumor growth [5,21].

Ultimately, although our discussion has focused on the role of PFKFB3 and other PFKFB family members, we fully acknowledge that the observed effects of PFKFB3 deletion on tumor growth may additionally be due to changes in multiple glycolytic enzymes or in other tumor growth pathways affected by deletion and the resultant decreased expression/activity of PFKFB3. Studies to evaluate these are currently underway and, if other pathways are determined to be involved, we anticipate that our model will enable the assessment of further potentially impactful combination strategies to ultimately improve outcomes in cancer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a novel and effective model of genomic deletion of a key regulator of glycolysis. Our studies have validated the efficacy of this model in vivo in decreasing oncogenedriven tumor growth. Most importantly, these studies have provided evidence of the efficacy of PFKFB3 inhibition as a therapy against cancer and data that provide potential future directions for the development of therapeutic strategies in combination with PFKFB3 inhibitors.

Authors' Contributions

The study was conceptualized by S.T.; Experiments were conducted by L.L. and S.T.; Original draft preparation by S.T.; Review and editing were conducted by L.L and S.T.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 144: 646-674.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marshall MJ, Goldberg DM, Neal FE, Millar DR (1978) Enzymes of glucose metabolism in carcinoma of the cervix and endometrium of the human uterus. Br J Cancer 37:990-1001.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weber G (1977) Enzymology of cancer cells: (Second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 296:541-551.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clem BF, O'Neal J, Tapolsky G, Clem AL, Imbert-Fernandez Y, et al. (2013) Targeting 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFKFB3) as a therapeutic strategy against cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 12:1461-1470.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kotowski K, Rosik J, Machaj F, Supplitt S, Wiczew D, et al. (2021) Role of PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 in cancer: Genetic basis, impact on disease development/progression, and potential as therapeutic targets. Cancers 13:909.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Imbert-Fernandez Y, Chang SM, Lanceta L, Sanders NM, Chesney J, et al. (2024) Genomic deletion of PFKFB3 decreases in vivo tumorigenesis. Cancers 16:2330.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB (2008) The biology of cancer: Metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab 7:11-20.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chesney J, Mitchell R, Benigni F, Bacher M, Spiegel L, et al. (1999) An inducible gene product for 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase with an AU-rich instability element: Role in tumor cell glycolysis and the Warburg effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:3047-3052.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okar DA, Lange AJ (1999) Fructose‐2, 6‐bisphosphate and control of carbohydrate metabolism in eukaryotes. Biofactors 10:1-4.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shi L, Pan H, Liu Z, Xie J, Han W (2017) Roles of PFKFB3 in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2:1-10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Cao I, Song MS, Hobbs RM, Laurent G, Giorgi C, et al. (2012) Systemic elevation of PTEN induces a tumor-suppressive metabolic state. Cell 149:49-62.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yalcin A, Clem BF, Simmons A, Lane A, Nelson K, et al. (2009) Nuclear targeting of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFKFB3) increases proliferation via cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem 284:24223-24232.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Telang S, Yalcin AB, Clem AL, Bucala R, Lane AN, et al. (2006) Ras transformation requires metabolic control by 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase. Oncogene 25:7225-7234.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Calvo MN, Bartrons R, Castano E, Perales JC, Navarro-Sabate A, et al. (2006) PFKFB3 gene silencing decreases glycolysis, induces cell-cycle delay and inhibits anchorage-independent growth in HeLa cells. FEBS Lett 580:3308-3314.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chesney J, Telang S, Yalcin A, Clem A, Wallis N, et al. (2005) Targeted disruption of inducible 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase results in embryonic lethality. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 331:139-146.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muller WJ, Sinn E, Pattengale PK, Wallace R, Leder P (1988) Single-step induction of mammary adenocarcinoma in transgenic mice bearing the activated c-neu oncogene. Cell 54:105-115.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson L, Mercer K, Greenbaum D, Bronson RT, Crowley D, et al. (2001) Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature 410:1111-1116.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Lu X, Huang L, Wang W, Jiang G, et al. (2014) Different thresholds of ZEB1 are required for Ras-mediated tumour initiation and metastasis. Nat Commun 5:5660.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chesney J, Clark J, Klarer AC, Imbert-Fernandez Y, Lane AN, et al. (2014) Fructose-2, 6-bisphosphate synthesis by 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2, 6-Bisphosphatase 4 (PFKFB4) is required for the glycolytic response to hypoxia and tumor growth. Oncotarget 5:6670.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sakata J, Abe Y, Uyeda K (1991) Molecular cloning of the DNA and expression and characterization of rat testes fructose-6-phosphate, 2-kinase: Fructose-2, 6-bisphosphatase. J Biol Chem 266:15764-15770.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chesney J, Clark J, Lanceta L, Trent JO, Telang S (2015) Targeting the sugar metabolism of tumors with a first-in-class 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFKFB4) inhibitor. Oncotarget 6:18001.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Lanceta L, Telang S (2024) Utility of a Novel Model of Genomic Deletion of 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6-Bisphosphatase (PFKFB3) in Developing Effective Anti-Cancer Strategies. J Oncol Res Treat. 9:295. DOI: 10.4172/aot-1000295

Copyright: © 2024 Lanceta L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits restricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 436

- [From(publication date): 0-0 - Apr 18, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 264

- PDF downloads: 172