Review Article Open Access

Underground Markets in the USA

Arthur Horton*Lewis University, One University Parkway Drive Romeovile, IL, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- Arthur Horton

Lewis University, One University Parkway

Drive Romeovile, IL, USA

Tel: 8158365314

E-mail: ahorton756@aol.com

Received date: April 03, 2015; Accepted date: May 29, 2015; Published date: June 05, 2015

Citation: Horton A (2015) Underground Markets in the USA. J Addict Res Ther 6:227. doi:10.4172/2155-6105.1000227

Copyright: © 2015 Horton A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy

Introduction

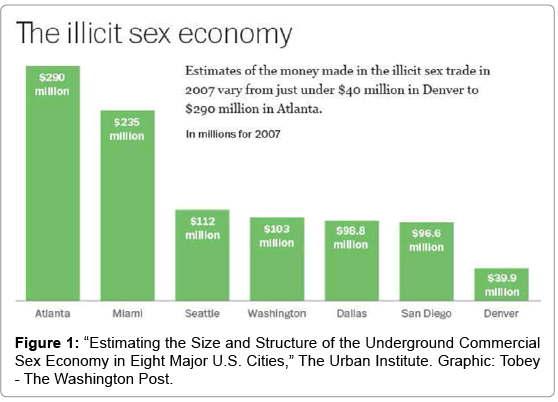

In major American cities like Seattle, Miami, and Atlanta, the local underground sex economy can rake in upward of $100 million a year. But the business leaders running these lucrative local industries are often obscured from view, publicly represented only by crude cultural stereotypes. So who are they? “I’m not a pimp,” one 27-year-old man imprisoned for pimping and pandering-related offenses told researchers at the Urban Institute when they interviewed him for a new sweeping report on the criminalized portion of the American sex economy. “I don’t believe in the word pimp. Pimp is like the tooth fairy, from the old ‘70s movies with big hats and big ol’ chains. That’s not me” (Figure 1).

The Urban Institute’s report draws on interviews with dozens of child pornographers, sex workers, pimps, traffickers, and local law enforcement officials in a bid to outline the inner workings of the business in eight American cities. The role of pimps, in particular, has been under investigated by social scientists. The Urban Institute begins to correct that oversight by speaking with 73 incarcerated pimps and traffickers, many of whom seemed eager to challenge cultural assumptions about pimping, starting with the word itself. Most of the Urban Institute’s subjects preferred to identify as business managers, businessmen, or madams.

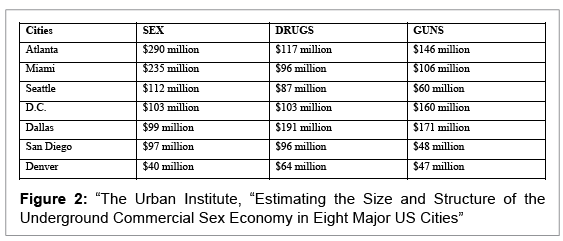

How the annual size of illicit markets for sex in seven major cities in 2007 compared with those for drugs and guns, according to estimates in a study commissioned by the Justice Department (Figure 2).

My perspective

Legalize, regulate and tax adult prostitution. Give those who may only temporarily resort to this type of dangerous behavior the ability to change their lives and move on without permanent criminal records that shackle them to this behavior and prevent them for seeking better employment. Provide vendors and patrons with sound health care information and safety guidelines. Use tax revenue to give these people services they need to change their position in life.

Focus on investigating and convicting those who exploit and/or abuse immigrants, children, women, drug addicts, TGLB persons; and focus on sex traffickers and violent sex offenders. The sex trades seem to mirror the drug trades in the US. Things in general have moved up steady in the past several years, it seems only natural for the two of them to move hand in hand. I’d like to know what the text books are saying ever since the US, under the administration of Ronald Mc Reagan declared war on drugs back in the 60’s. It is eating away at us like a cancer, Reagan once said, and he may have been correct. The harm reduction model is committed to reducing drug-related harm among individuals and communities. It initiates and promotes local, regional, and national harm-reduction education, interventions, and community efforts. It fosters alternative models to conventional health and human services and drug treatment. It challenges traditional client/ provider relationships. It provides resources, educational materials, and support to health professionals and drug users in their communities to address drug-related harm. It believes in every individual’s right to health and well-being, and believes they are competent to protect and help themselves, their loved ones, and their communities.

What is harm reduction: Harm reduction is a set of practical strategies that reduce negative consequences of drug use, incorporating strategies from safer use, to managed use, to abstinence. Harm reduction strategies meet drug users where they’re at, addressing conditions of use along with the use itself.

Because harm reduction demands that interventions and policies designed to serve drug users reflect specific individual and community needs, there is no universal definition of or formula for implementing harm reduction. However, the following principles seem central to harm reduction practice.

• Accepts, for better and for worse that licit and illicit drug use is part of our world and chooses to work to minimize its harmful effects rather than simply ignore or condemn them.

• Understands drug use as a complex, multi-faceted phenomenon that encompasses a continuum of behaviors from severe abuse to total abstinence, and acknowledges that some ways of using drugs are clearly safer than others. Establishes quality of individual and community life and well-being -- not necessarily cessation of all drug use -- as the criteria for successful interventions and policies.

• Calls for the non-judgmental, non-coercive provision of services and resources to people who use drugs and the communities in which they live in order to assist them in reducing attendant harm.

• Ensures that drug users and those with a history of drug use routinely have a real voice in the creation of programs and policies designed to serve them.

• Affirms drugs users themselves as the primary agents of reducing the harms of their drug use, and seeks to empower users to share information and support each other in strategies which meet their actual conditions of use.

• Recognizes that the realities of poverty, class, racism, social isolation, past trauma, sex-based discrimination and other social inequalities affect both people’s vulnerability to and capacity for effectively dealing with drug-related harm.

• Does not attempt to minimize or ignore the real and tragic harm and danger associated with licit and illicit drug use.

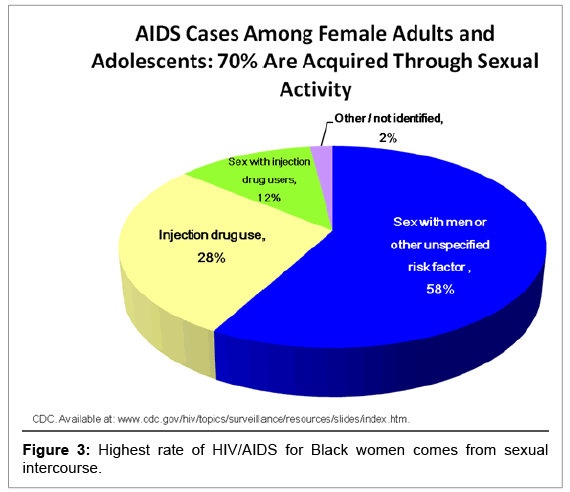

Apparently, African American females particularly adolescents are being infected through unprotected sexual intercourse, drug use, and interpersonal violence. In the United States, approximately 1.3 million women are physically assaulted by an intimate partner compared to 835,000 men [1]. According to the 2005 U.S. National Violence against Women Survey, 64 percent of women who reported being raped, physically assaulted, or stalked by a current or former husband, cohabiting partner, boyfriend, or date victimized since age 18. In addition, one in six women has experienced an attempted or completed rape—defined as a forced or threatened vaginal, oral or anal penetration—in her lifetime; and many are raped at an early age [1]. Of the 18 percent of all women surveyed who said they had been the victim of a completed or attempted rape at some time in their lives, 22 percent were younger than age 12 when they were first raped, and 32 percent were ages 12 to 17 years [1]. The highest rate of HIV/AIDS for Black women comes from sexual intercourse, followed by drug use. Figure 3 gives some of the details. Substance abuse and alcohol abuses are risk factor for non-adherence to ARV treatment. Because a relatively large proportion of black females who carry the disease live in poverty, there is minimal health care, either as prevention measure or maintenance of health with the virus. They are not educated enough on the issues of sex or AIDS, so many are ignorant to the AIDS virus, along with other sexually transmitted diseases (STD), consequently many times they go undiagnosed. Poverty, discrimination, and possibly the non-adherence of black women to ARV treatment also play an important role in the death rates (Figure 3).

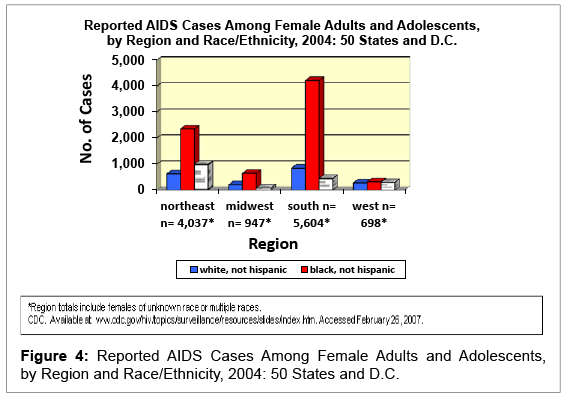

The profession of social work and other behavioral health experts can take the lead in the arena of primary prevention and health promotion. Safe sex or no sex is a matter of individual choice but appropriate education as to the consequences of such choices transcends choice. The profession can help advance access to healthcare, useful instructions from healthcare providers to individuals, families, communities and the overall satisfaction with the healthcare system (Figure 4).

Now as to effective treatment both Mark Sanders and Fred Dyer have join the chorus of those of those calling for evidence–based treatment. The National Institute on Drug abuse 1999 conducted an extensive review of the treatment outcome research literature in the area of adolescent substance abuse as noted by Randall and colleagues [2]. These principles have important implications for conceptualizing the nature of effective services for substance abusing adolescents.

• No single treatment is appropriate for all individuals.

• Treatment needs to be readily available

• Effective treatment attends to the multiple needs of the individual.

• An individual’s treatment and service plan must be assessed continually.

• Remaining in treatment for an adequate period of time is critical for treatment effectiveness.

• Counseling and other behavioral therapies are critical components of an effective treatment for addiction.

• Medications are an important element of treatment for adolescent, especially when combined with counseling and other behavioral therapies.

• Addicted or drug using adolescents with co-existing mental disorders should have both disorders treated in an integrated fashion.

• Medical detoxification is only the first stage of addiction treatment and by itself does little to change the long –term drug use.

• Treatment does not need to be voluntary to be effective.

• Possible drug use during treatment must be monitored continuously.

How can this concept of harm reduction be applied to adolescents? The majority of adolescents are not going to require the kind of harm reduction strategies mentioned above.

However, a harm reduction approach is congruent with what we know about adolescent development and decision-making. Adolescence is a time of experimentation and risk-taking. Adolescents also tend to reject authority and strive for autonomy in their decisionmaking. Young people engage in behaviors that have potentially negative outcomes.

In one study [3], more than two-thirds of high school students in Ontario reported having used alcohol at least once over the previous year, and one-third reported cannabis use over the previous year. Alcohol ingestion presents the potential for intoxication and overdosing (particularly when binge drinking occurs). Alcohol disinhibits an individual, which may promote aggressive behavior and fighting, or which may be associated with unwanted sexual advances or experiences. Between 8% and 10% of teens reported that using drugs or alcohol was the reason that they had intercourse for the first time [4].

Unprotected sexual activity is associated with a higher incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and can lead to unintended pregnancy. In fact, the highest rates of STIs in Canada are in the 15- to 24-year age group, with girls 15 to 19 years of age having the highest rates for chlamydia and gonorrhea. The 2002 Canadian Youth, Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS [5]. Study reported that while the age at initiation of intercourse is decreasing gradually over time, the median age for first intercourse has not changed in over a decade and remains around 17 years of age. Almost 30% of boys and girls in grade 9 reported having had oral sex.

Overall, long-term trends have shown some changes in these behaviors over time; however, it is highly unlikely that any interventions will eliminate these behaviors from adolescence. It is conceivable, however, that enhanced strategies will be developed, with the aim of slowing down some of the trends seen over the past decade. This would include trends of decreasing age at first use of substances such as cannabis and earlier ages of onset of sexual activity.

There are several possible approaches to substance use and other risky behaviors:

• Discourage the behavior (i.e., recommend that the teen stop the behavior completely);

• Encourage the teen to reduce the behavior; and

• Provide the teen with information aimed at reducing the harmful consequences of the behavior when it occurs.

Some Studies Council of Ministers of Education, Canada Canadian Youth, Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS from the substance use literature have identified that the perceived risk of harm is inversely related to the level of use. The provision of education about the potential risks and ways of reducing them may impact on these behaviors. It is important to acknowledge that programs aimed at the primary prevention of a particular behavior need to differ in focus from those aimed at secondary prevention in grows ups of adolescents in which the behavior is already established. This requires careful consideration of the intended target population and the context in which the approach is used [6].

Primary prevention of risky behavior is a reasonable focus for the young adolescent or preteen. This may be achieved by discouraging the behavior (using sexual behavior as an example – by encouraging the delay of initiation of sexual activity). For an adolescent who is already engaging in potentially risky sexual behavior, he or she can be encouraged to reduce the behavior, and can also be provided with information and education about condom use, additional contraception, and discussion about the pros and cons of sexual activity. For a streetinvolved young woman who is engaging in prostitution, providing free condoms, as well as regular access to STI testing and emergency contraception (in addition to other biopsychosocial care), may be the most appropriate intervention at the time. This would, however, not preclude the discussion of the option of reduction or elimination of the risky behavior [7].

There is a growing literature supporting the efficacy of harm reduction strategies in both the prevention and intervention of behavior with potential health risks. Marlatt and Witkiewitz [5] published a comprehensive review of harm reduction approaches to alcohol use, and summarized the relevant literature on health promotion prevention and treatment. They discussed the data on a program that was widely implemented in the United States, a program known as Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE), which focused on zero tolerance (the ‘just say no’ concept). Several studies have demonstrated that this program was non efficacious in reducing substance use. Two examples of programs that have been successfully implemented and evaluated based on a harm reduction philosophy are the Alcohol Misuse Prevention Study (AMPS) in the United States, and the School Health and Alcohol Harm Reduction Project (SHAHRP) in Australia [8].

The AMPS program is a curriculum aimed at grade 5 and grade 6 students, and includes information about the harms of alcohol abuse and how to deal with social pressures to misuse alcohol. In a randomized, controlled study, participants in the AMPS program had significantly fewer alcohol problems than controls. The program has also demonstrated reductions in the normative increases in alcohol use and misuse in early to late adolescence. Public Health Agency of Canada Canadian sexually transmitted infections surveillance report 2004.

The SHAHRP program has similar components to the AMPS program, and consists of active learning incorporating skills training and alcohol education. Evaluation of this program has demonstrated significant reductions in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms in those students participating in the program compared with controls). 2004.

An approach complementary to harm reduction model

A group of women sit around a table in an upstairs room of a church on Milwaukee’s north side.

Some have mugs of coffee in front of them. Others have pastries or other snacks nearby.

Today’s topic: anger. The women take turns speaking, and whoever is holding a plush frog has the floor.

The words tumble out as the women express their frustrations: from the everyday concerns — their kids aren’t listening to them, or they’re trying to move to a safer

Neighborhood - to deeper trauma, like abusive relationships, abandonment and sexual assault.

For many of the women, it’s the first time anyone has asked about their lives and their feelings.

“Anger is an emotion that is real,” said Donna Hietpas, who leads the group. “It’s never going away.”

The women are at the Sisters Program because they were arrested for prostitution and given a choice: a ticket and a fine, or a minimum of six months of participating at Sisters.

The program, housed in Reformation Lutheran Church, 2201 N. 35th St., is a collaborative effort among the Benedict Center — an interfaith, nonprofit agency that focuses on criminal justice reforms and is celebrating its 40th anniversary on Thursday — the Milwaukee County district attorney’s office and the Milwaukee Police Department District 3. A grant from the Healthier Wisconsin Partnership Project provides funding.

“I think it’s an innovative solution to what has, frankly, been an old problem and one in which traditional methods of arrest and incarceration is really just a rotating door,” said Jeanne Geraci, the Benedict Center’s executive director.

“It’s frustrating for the police and the residents, and frankly it was not helping the women get to any better place,” she said.

Sisters started small, offering just one day of programming per week in 2011. After receiving a grant with a new partner, the Medical College of Wisconsin, Sisters expanded last year. [9]

The expansion allowed for the hiring of two part-time outreach workers, themselves graduates of Benedict Center programming, who visit Lisbon and North avenues to engage women involved in street sex work. They try to build trusting relationships and offer the women bagged lunches, hygiene products and referrals to Sisters and other resources.

Researchers from the Medical College are analyzing data about the women and the program, trying to measure progress and build a best-practices model. Already, officials in Cook County Illinois have expressed interest in creating a similar program.

The Benedict Center previously worked with the district attorney’s office on deferred prosecutions for state-level charges related to prostitution, but the options were few for women who received municipal tickets. The tickets could add up, leading to warrants and arrest records that made landlords hesitant to rent to them.

Prostitution has long been a problem in District 3, in the northcentral part of the city, particularly along Lisbon Ave., said Assistant District Attorney Chris Ladwig, who joined the district’s community prosecution unit in 2010.

“When I first got here, we did a big sweep and arrested a lot of females and over a period of time what we saw was, this doesn’t seem to work very well, just arresting and prosecuting without really any kind of good interventions,” Ladwig said. “But we did have success with women we were putting into the Benedict Center program with deferred prosecution.” [10,11]

Now, officers write the tickets, but instead of issuing them, officers can take the women directly to the Benedict Center. If the women complete a six-month program, their tickets are never issued.

The officers also look for signs of human trafficking among women on the streets, police Capt. Jason Smith said.

“Human trafficking is a hidden crime,” he said. “It resides in other markers. We have to teach people to look and ask the next question.”

A teen girl who is repeatedly reported missing, for example, should trigger officers to look more deeply at the case because studies have shown many children who are victims of trafficking had been previously reported missing.

And a 45-year-old woman working independently on the street could have similarities with someone who was and incarceration are really just a rotating door,” said Jeanne Geraci, the Benedict Center’s executive director.

“It’s frustrating for the police and the residents, and frankly it was not helping the women get to any better place,” she said.

Drug use and its effects are huge challenges. They require the coordinated efforts of treatment specialists, law enforcement agents, public health professionals, corrections experts, and drug users, themselves. Harm reduction suggests that drug treatment is usually more effective than arrest and imprisonment. It also says that the best approach to drug use problems involves public health providers working with drug users rather than imposing legal punishment. Exceptions would be where drug use results in criminal activity that harms others, such as theft, violence, and driving under the influence of drug. Many communities combine harm reduction and law enforcement approaches to drug use. Unfortunately, many debates about drug policy put public health arguments on one side against morality and law enforcement on the other [12-14].

Is harm reduction legal: Some aspects of harm reduction are legal. Drug users can get information on methadone, on using drugs more safely, or referrals to drug treatment programs. In some states, people can purchase syringes without a prescription or obtain medications to reverse a drug overdose. People can get information on reducing the risk of HIV infection through sexual activity and can get condoms. Some countries (not the US) have set up safe injection sites for drug users. At these sites, clean syringes and medical care are available.

Many other aspects of harm reduction require changes in laws or in law enforcement procedures. For example, syringe exchange programs operate under specific exemptions to existing laws or local “emergency” legislation. Programs to permit the purchase of new syringes without a prescription, or to distribute medications to prevent overdose, also require changes in laws. These legal changes may require cooperation from local law enforcement officials.

Before concluding the paper, I would like to make a brief comment. Because it falls outside the scope of this paper the issue of adolescent relapse has not been addressed however one must be aware of such an outcome. Recovering adolescents are at risk of relapse because they are in a stage of growth, which involves many physical and emotional changes. Chemical dependence delays normal adolescent development. This makes it difficult for recovering adolescents to function in ways that fit their age. This can cause them to be very uncomfortable, sometimes to the point of being dysfunctional in the way they think, feel, and behave. Sometimes relapsing adolescents return to using alcohol and drugs to medicate this discomfort [14-16].

In conclusion, I do believe that many of these teens are presenting with many varied problems but the wrong questions are being asked. Concentrated efforts should occur in educating providers both professional and lay to ask teens better questions which will elicit more authentic answers. I do not think this is only true to substance abuse but for mental health issues as well. As a country, financial support needs to be amplified to those organization’s individuals that treat our youth. We have to target the next generation of upcoming adults, so as to reduce prison, jail and hospital stays as well as needless/preventable social costs, thus increasing their opportunities for fruitful, intimate relationships.

References

- CDC (2006) Extent, nature and consequences of rape victimization: Findings from the National violence against women survey Washington DC: U.S .Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

- file:///C:/Users/punit-p/Downloads/IntensiveinterventioninGreenwichforfamilieswithc.pdf

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Drug use among Ontario students, 1977–2007: OSDUHS highlights.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2528824/#b10-pch13053

- Council of Ministers of Education, Canada Canadian Youth, Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS Study: Factors influencing knowledge, attitudes and behaviours.

- Masterman PW, Kelly AB (2003) Reaching adolescents who drink harmfully: Fitting intervention to developmental reality.J Subst Abuse Treat24: 347-55

- Public Health Agency of Canada Canadian sexually transmitted infections surveillance report( 2004

- McBride N, Farringdon F, Midford R, Meuleners L, Phillips M(2004) Harm minimization in school drug education: Final results of the School Health and Alcohol Harm Reduction Project (SHAHRP)Add iction 99:278–91.

- CDC (Center for Disease Control) (2004) HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 16:1-46

- http://www.blackwomenshealth.org/site/News2?page=NewsArticle&id=6594

- http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/resources/factsheets/women.htm

- Meredith Dank, Bilal Khan, P. Mitchell Downey, Cybele Kotonias, Debbie Mayer, et al. (2014)Estimating the Size and Structure of the Underground Commercial Sex Economy in Eight Major US Cities, Urban Institute, New York

- Sullivan Gail (2014) Study sheds light on dark sex trafficking industry, Washington Post.

- Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K (2002) Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: Health promotion, prevention, and treatment.Addict Behav27:867–86

- Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, Marlatt GA, Sturge J, et al. (2007) Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use.Lancet 369:1391–401

Relevant Topics

- Addiction Recovery

- Alcohol Addiction Treatment

- Alcohol Rehabilitation

- Amphetamine Addiction

- Amphetamine-Related Disorders

- Cocaine Addiction

- Cocaine-Related Disorders

- Computer Addiction Research

- Drug Addiction Treatment

- Drug Rehabilitation

- Facts About Alcoholism

- Food Addiction Research

- Heroin Addiction Treatment

- Holistic Addiction Treatment

- Hospital-Addiction Syndrome

- Morphine Addiction

- Munchausen Syndrome

- Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

- Nutritional Suitability

- Opioid-Related Disorders

- Relapse prevention

- Substance-Related Disorders

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14312

- [From(publication date):

June-2015 - Jul 13, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9749

- PDF downloads : 4563