Case Report Open Access

The Traumatic Etiology Hypothesis of Traumatic Bone Cyst: Overview and Report of a Case

Ahmed S Salem*, Ehab Abdelfadil, Samah I Mourad and Fouad Al-Belasy

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

- *Corresponding Author:

- Ahmed S Salem

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Faculty of Dentistry, Mansoura University

Mansoura, Egypt

Tel: 01002242457

Phone/Fax: +2-050-226-0173

E-mail: ahmedsobhysalem@yahoo.com

Received Date: March 23, 2013; Accepted Date: April 24, 2013; Published Date: April 27, 2013

Citation: Salem AS, Abdelfadil E, Mourad SI, Al-Belasy F (2013) The Traumatic Etiology Hypothesis of Traumatic Bone Cyst: Overview and Report of a Case. J Oral Hyg Health 1:101. doi: 10.4172/2332-0702.1000101

Copyright: © 2013 Salem AS et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Oral Hygiene & Health

Abstract

The Traumatic Bone Cyst (TBC) is an uncommon intraosseous non-neoplastic lesion of the jaws that almost affects patients in the second decade of life. The literature is replete with a multitude of names that refer to this lesion; underscoring ignorance of its etiopathogenesis. We present an overview of TBC and report a case that further corroborates one of its proposed etiologic hypotheses. The patient was a young male whose mandible was the jaw affected. The lesion was asymptomatic and discovered on routine radiographic examination. At operation, the bony cavity was seen almost empty and the scant material available for histological examination showed features consistent with the definitive diagnosis of the lesion.

Keywords

Traumatic bone cyst; Etiopathogenesis

Introduction

The traumatic bone cyst (TBC), first described many decades ago, has been denominated with a plethora of names including: simple bone cyst, solitary bone cyst, hemorrhagic bone cyst, extravasation cyst, idiopathic bone cyst, and primary bone cyst. However, the term TBC is more widely used in the literature [1].

The TBC is an intraosseous non-neoplastic lesion of the jaws that almost affects patients in the second decade of life with controversial sex predilection [2,3]. The majority of TBCs occurring in the maxillofacial region are located in the mandible mainly in the body or symphysis area with only a few cases reported in the condyle [2]. Maxillary lesions tend to be uncommon, although the reasons for this are unclear [4]. The lesion is generally asymptomatic in the majority of cases and is often accidentally discovered on routine radiological examination [1,3]. However, some patients present with pain, swelling, tooth sensitivity, and less commonly with fistula, root resorption, paresthesia, delayed eruption of permanent teeth, buccal and lingual bony expansion, and pathological fracture of the mandible [3,5].

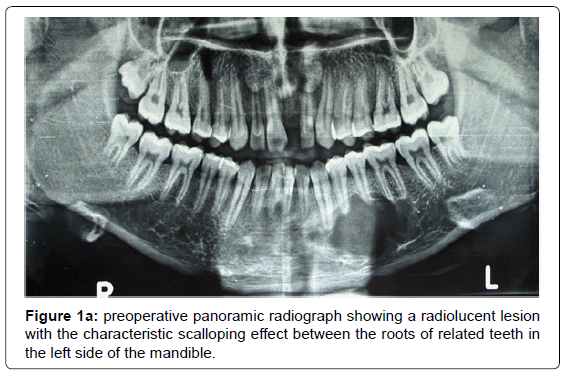

Radiographically, TBC usually appears as an isolated unilocular radiolucent area with an irregular well defined or poorly defined outline with or without sclerotic margin [5]. Characteristic for the TBC is the “scalloping effect” when extending between the roots of the teeth [5,6]. TBC, in most cases, is within the medullary bone and expansion of the cortical bone is rarely present [1]. Multilocular lesions are too seldom to find [5], albeit multilocularity with septum-like images may appear in some cases-thus evoking other possible lesions [6].

Surgery is the management of choice [7]. It serves as both a diagnostic maneuver and a definitive therapy [3]. The surgical operation consists of complete exploration of the area with curettage of the bony defect in order to stimulate bleeding into the cavity [8]. This is followed by the formation and organization of a blood clot, and healing by the formation of new bone [3,9]. Recurrence of TBC is assumed to be extremely rare [8,10]. However, a distinct proportion of recurrences may occur, which may be larger than the original lesions [10].

Definitive histological diagnosis is often difficult to achieve since material for histological examination may be scant or nonexistent [10]. However, most of the histological findings reveal fibrous connective tissue and normal bone with no evidence of an epithelial lining. The lesion may also exhibit areas of vascularity, fibrin, erythrocytes, cholesterol clefts, and occasional giant cells adjacent to the bone surface [6,8].

The etiopathogenesis of TBC is still unknown. Cohen [11] proposed that the cyst develops because of a lack of collateral lymphatic drainage of venous sinusoids. This apparent blockage then results in the entrapment of interstitial fluid causing resorption of the bony trabeculae and cyst development. Mirra et al. [12] proposed that TBCs are synovial cysts, developing as a result of a developmental anomaly whereby synovial tissue is incorporated intraosseously. Other hypotheses proposed for the evolution of TBC include; bone tumor degeneration, altered calcium metabolism, low-grade infection, local alteration in bone growth, increased osteolysis, intramedullary bleeding, local ischemia or a combination of such factors [2,13]. Alternatively, Kuhmichel and Bouloux [4] proposed that TBCs appear to be developmental in nature. However, among the myriad of these proposed hypotheses, there are only 3 that predominate: a degenerative tumoral process, an abnormality of osseous growth, and a particular factor triggering hemorrhagic trauma [6]. The purpose of this report is to further document a case that corroborates the hypothesis of traumatic etiology in the evolution of TBC.

Case Report

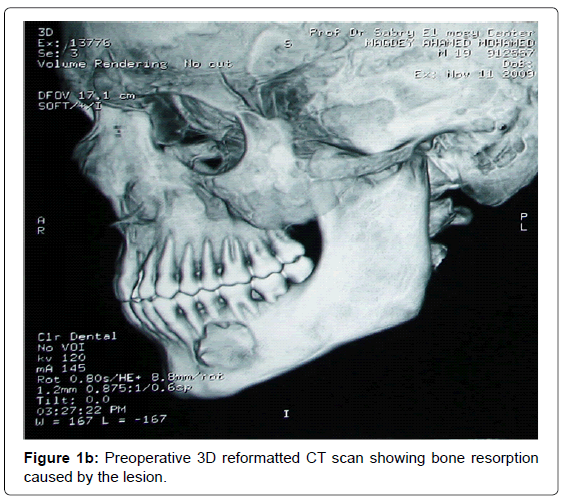

A 16-year-old male presented to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Faculty of Dentistry, Mansoura University, asking for replacement of his missing maxillary left central incisor with a dental implant. The medical history of the patient was noncontributory. The dental history, however, revealed a previous visit to a dentist who took out the patient’s maxillary left central incisor after a fall where his face was struck to the ground. This accident was almost 3 years before presentation. Additionally, the patient recalled an incident with no definition of time that his lower jaw was hit by a hard object thrown at him by his mentor during his apprenticeship in fixing tires. Upon screening with a panoramic radiograph, a large scalloped radiolucent lesion was detected extending from the lateral incisor to the first molar of the left mandibular body (Figures 1a and b). The patient had no symptoms in relation to the accidentally found lesion, and there was no extraoral evidence of the presence of the lesion. However, careful intraoral examination revealed slight cortical expansion of the affected area with no soft tissue changes. Periodontium was healthy with no evidence of gingivitis, and all the involved teeth were vital with no caries or mobility. Aspiration of the lesion yielded a small amount of brownish-red sanguineous fluid. A tentative diagnosis of TBC was made and the patient scheduled for surgical exploration and excisional biopsy of the lesion under local anesthesia.

During surgery, the cavity was seen almost empty and devoid of any lining but careful curettage of the lesion yielded a small amount of tissue that was sent for histopathological examination. Microscopic examination revealed numerous cholesterol clefts with intervening inflammatory cells, occasional giant cells, and osteoid tissue. These features were consistent with a TBC.

Discussion

The multitude of the names applied to the TBC attests to the lack of understanding of the true etiology and pathogenesis [3]. Trauma has been said to be the most accepted hypothesis proposed for the evolution of TBC [6]. Trauma may be defined many ways but is conventionally understood to refer to an injury to living tissue caused by a force or mechanism extrinsic to the body [14]. Scholars generally refer to both accidental and intentional trauma, the former usually including most fractures and the latter usually including examples of surgical intervention [14]. In some instances, however, accidental trauma may not be sufficient to fracture a healthy bone [6]. Both trauma insufficient to fracture a healthy bone and iatrogenic trauma induced by either tooth extraction [15] or orthodontic treatment [1] have been implicated as inciting factors in TBC formation. Thoma [16] stated that a previous definite injury of the affected part of the jaw is contained in the history of most cases and noted that this injury may have occurred several years before the discovery of the lesion. Figures for the history of trauma vary widely from 17% to 70% [3]. In Howe’s series [13], over one-half of the patients had a definite history of trauma and the severity of trauma was noted as a striking feature in most of the cases.

The explanation underlying the hypothesis of trauma is that TBC arises from a focus of intramedullary hemorrhage that causes a hematoma after trauma insufficient to fracture a healthy bone [3,6]. This hematoma subsequently liquefies and fails to organize and be replaced with tissue [17]. Liquefaction then induces continued transudation of fluid into the cyst with increasing internal pressure. This build-up of internal pressure causes venous stasis that leads to an area of bone marrow necrosis and osteoclastic resorption attributable to decreased tissue pH [13,16]. However, the process by which osteoclasts differentiate remains unknown [6]. A predisposing idiosyncratic factor in the pathogenesis of TBC was also suggested, such as a peculiarity of the vessel wall or an abnormal coagulation of the blood [16]. At large, the osteolytic pathogenesis might be due to an alteration of the vascular system causing a post-hemorrhagic ischemia, responsible for aseptic bone necrosis as well as an intracystic transudate whose enzymatic factors contribute to the bone resorption [6].

As long as the etiopathogenesis of a lesion is not clearly understood, proposed hypotheses will be subject to challenge, and the traumatic etiology hypothesis of TBC evolution is not an exception. Major opposition to this hypothesis is the absence of a clear history of trauma in many cases [9]. In addition, the incidence of trauma in patients with TBC is no greater than in the general population [8] and no difference in the prevalence of TBC exists between males and females, despite a higher incidence of trauma in males [4]. However, predisposing idiosyncratic factors as well as bone marrow spaces are not the same in the general population and those inflicted with TBCs. Sex predilection is controversial with some reports suggesting no differences in terms of gender [13], more common in males [8], and more frequent in females [7]. The argument that males are more subject to trauma than females cannot be taken for granted because the male-to-female ratio was found to be in direct relation to the nature of societies [18]. In Australia, Queensland, when comparing injuries sustained as a result of motorcycle injuries per motorcycle license, females outnumbered males, 1.5:1 [19]. From another perspective, failure to communicate data about lesions with questionable pathogenesis especially in published papers [2] may contribute negatively in the search for corroboration.

The predominance of TBCs in the mandibles of young patients may stand in support of the hypothesis of traumatic etiology. However, reaching any final conclusion cannot be met without answering questions regarding mode, intensity, frequency, and pathogenesis [3]. Therefore, clear, complete and detailed reporting of cases is the only way to collect materials for analysis of these problems [3]. Our patient was a young male whose mandible was the jaw affected. The lesion, extending from the lateral incisor to the first molar of the left mandibular body, was asymptomatic and discovered on routine radiographic examination as a unilocular radiolucent lesion with the characteristic scalloping feature. Upon probing the patient’s history, he recalled 2 incidents of past trauma to the jaws. At operation, the lesion was seen empty with no evidence of cyst fluid or evidence of synovial or epithelial lining. The scant material available for histological examination showed numerous cholesterol clefts with intervening inflammatory cells, occasional giant cells, and osteoid tissue. Therefore, these findings challenged the collateral lymphatic drainage blockage theory and the synovial tissue entrapment theory proposed for the etiopathogenesis of TBC. The hypothetical degeneration of a tumoral process or abnormality of osseous growth was difficult to verify because of the accidental discovery of the lesion. However, the clinical, radiographic, surgical, and histopathological findings of the case as well as the history of previous trauma to the jaw were consistent with the literature that fit the traumatic-hemorrhagic theory. Therefore, we believe that this current case further documents the posttraumatic evolution of TBC and corroborates one of the theories of its etiopathogenesis; traumatism.

References

- Motta AFJ, Torres SR, Coutinho ACA (2007) Traumatic bone cyst-report of a case diagnosed after orthodontic treatment. Rev Odonto Cienc, Porto Alegre 22: 377-381.

- Tanaka H, Westesson PL, Emmings FG, Marashi AH (1996) Simple bone cyst of the mandibular condyle: report a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 54: 1454-1458.

- Xanthinaki AA, Choupis KI, Tosios K, Pagkalos VA, Papanikolaou SI (2006) Traumatic bone cyst of the mandible of possible iatrogenic origin: a case report and brief review of the literature. Head Face Med 2: 40.

- Kuhmichel A, Bouloux GF (2010) Multifocal traumatic bone cysts: case report and current thoughts on etiology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 68: 208-212.

- Copete MA, Kawamata A, Langlais RP (1998) Solitary bone cyst of the jaws: radiographic review of 44 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 85: 221-225.

- Harnet JC, Lombardi T, Klewansky P, Rieger J, Tempe MH, et al. (2008) Solitary bone cyst of the jaws: a review of the etiopathogenic hypotheses. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 66: 2345-2348.

- Cortell-Ballester I, Figueiredo R, Berini-Aytés L, Gay-Escoda C (2009) Traumatic bone cyst: a retrospective study of 21 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 14: E239-E243.

- Kaugars GE, Cale AE (1987) Traumatic bone cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 63: 318-324.

- Tong AC, Ng IO, Yan BS (2003) Variations in clinical presentations of the simple bone cyst: report of cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 61: 1487-1491.

- MacDonald-Jankowski DS (1995) Traumatic bone cysts in the jaws of a Hong Kong Chinese population. Clin Radiol 50: 787-791.

- COHEN J (1960) Simple bone cysts. Studies of cyst fluid in six cases with a theory of pathogenesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 42-42A: 609-616.

- Mirra JM, Bernard GW, Bullough PG, Johnston W, Mink G (1978) Cementum-like bone production in solitary bone cysts. (so-called "cementoma" of long bones). Report of three cases. Electron microscopic observations supporting a synovial origin to the simple bone cyst. Clin Orthop Relat Res 135: 295-307.

- Howe GL (1965) 'Haemorrhagic cysts' of the mandible. I. Br J Oral Surg 3: 55-76.

- Lovell NC (1997) Trauma analysis in paleopathology. Yearbook of Physic Anthrop 40: 139-170.

- Pogrel MA (1987) A solitary bone cyst possibly caused by removal of an impacted third molar. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 45: 721-723.

- Thoma KH (1955) A symposium on bone cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 8: 899-901.

- Magliocca KR, Edwards SP, Helman JI (2007) Traumatic bone cyst of the condylar region: report of 2 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 65: 1247-1250.

- Al Ahmed HE, Jaber MA, Abu Fanas SH, Karas M (2004) The pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: a review of 230 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 98: 166-170.

- Wood EB, Freer TJ (2001) Incidence and aetiology of facial injuries resulting from motor vehicle accidents in Queensland for a three-year period. Aust Dent J 46: 284-288.

Relevant Topics

- Advanced Bleeding Gums

- Advanced Receeding Gums

- Bleeding Gums

- Children’s Oral Health

- Coronal Fracture

- Dental Anestheia and Sedation

- Dental Plaque

- Dental Radiology

- Dentistry and Diabetes

- Fluoride Treatments

- Gum Cancer

- Gum Infection

- Occlusal Splint

- Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology

- Oral Hygiene

- Oral Hygiene Blogs

- Oral Hygiene Case Reports

- Oral Hygiene Practice

- Oral Leukoplakia

- Oral Microbiome

- Oral Rehydration

- Oral Surgery Special Issue

- Orthodontistry

- Periodontal Disease Management

- Periodontistry

- Root Canal Treatment

- Tele-Dentistry

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 20586

- [From(publication date):

July-2013 - Nov 21, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 15899

- PDF downloads : 4687