The Strategies and Mechanisms for effective promotion of minority rights to minimize conflict in Zimbabwe

Received: 26-Jul-2021 / Accepted Date: 24-Aug-2021 / Published Date: 31-Aug-2021 DOI: 10.4172/2169-0170.1000283

Abstract

This paper argues that for effective respect, protection and promotion of minority rights to take place in modern day society, it must be supported by strong institutions and well-crafted pieces of legislation. The purpose of this research paper is to examine the strategies and mechanisms to protect, respect and promote minority rights by taking a careful and surgical analysis of the role of the government of Zimbabwe in promoting minority rights in the country. The paper argues that for effective protection and promotion of minority rights to occur, it must include those most affected in society and it must have platforms for sharing and collaboration. The paper starts with definitions of key concepts such as human rights, minority, minority rights and minority groups. The central argument of this research is that there is dire need to effectively protect and promote minority rights in Zimbabwe. In addition, there can be more effective strategies and mechanisms to protect and promote minority rights in Zimbabwe. The major findings were that Zimbabwe made a whole mark achievement in crafting the 2013 constitution which succinctly addresses the rights of minorities in tandem with international law and best practice compared to the Lancaster house constitution which was totally silent on minority rights. Furthermore, some of the rights provided for in the 2013 constitution are just aspirational as they only exist at policy level but are not implemented on the ground. The policy implications deriving from this research are that there is dire need to create strong institutions and implementation strategies for minority groups so that they seek redress in the event of an infringement. Furthermore, minority oppression and assimilations were entrenched by discriminatory and weak policies and pieces of legislation which made minority groups fail to fully enjoy their rights. The paper further seeks to analyze the effects of the different legislative mechanisms on respecting, promoting and protecting minority rights in Zimbabwe to achieve socio-economic development. The duty bearer, the right holder and the core interests of these pieces of legislation in effectively promoting minority rights will be subjected to detailed scrutiny. Recommendations for improvement will also be proffered on more effective strategies to respect, protect and promote minority rights.

Keywords

Minority; Minority Rights; Human Rights; Minority Groups

Introduction

Minority rights need to be protected, promoted and respected by governments and society at large. The non-recognition of minority groups in society may lead to their assimilation and resultantly extinction and hence the dire need to protect them so that they remain in existence and enjoy their rights to the fullest.

There is no single definition of minority where all scholars agree. Though that is the case, it is crucial to start by tracing the historical development of the concept. It dates back to ancient times when new states were created after World War 1 and World War 11. This saw a mixture of religious, racial and linguistic groups and minorities were found in some of these countries. In view of above, it is not easy to give a comprehensive definition of the concept of minority. To explicitly illustrate this challenge, Mihandoost and Babajanian argued that “Although it is academically difficult to present a really precise definition of minority…in fact ‘minority’ is used in a more limited sense today. In the present, it is commonly applied to a special group of society that has been distinguished from the superior group living in the country.” This is clear evidence of the struggle of having a wholly acceptable definition of minority [1]. This observation corroborates well with the findings of the United Nations which examines that “There is no internationally agreed definition as to which groups constitute minorities. The difficulty in arriving at a widely acceptable definition lies in the variety of situations in which minorities live.” One can wherefore contend that the definition of minority can be contextualized depending on the situational analysis conducted [2].

Appiagyei-Atua defines minority as “A group numerically inferior to the rest of the population of a State, in a non-dominant position, whose members being nationals of the Statepossess ethnic, religious or linguistic characteristics differing from those of the rest of the population and show, if only implicitly, a sense of solidarity, directed towards preserving their culture, traditions, religion or language” [3]. It is crucial to observe that a common trend is that minorities are in a non-dominant position. This paper defines minority simply as the small group of people in a country that is easily identifiable and is unique in terms of its religion, race, gender or culture that does not participate in the country’s governance systems.

To that end, (p.16) asserts that “A minority is a group of country’s subjects that constitute a small proportion of population and do not participate in the country’s government and ethnic, religious, or lingual properties different from the majority of the society…” Minority rights advocate for the full participation of minority groups in the governance system of their countries.

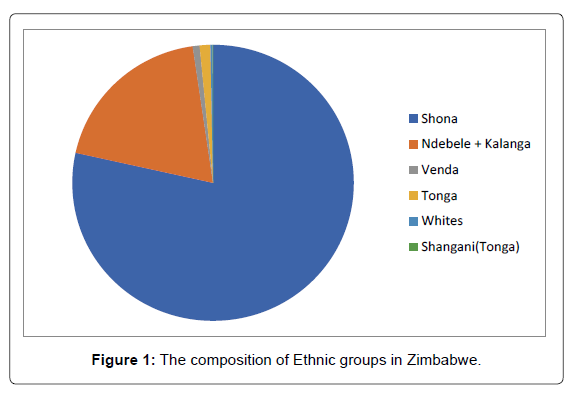

According to (p. 16), minority group “is a term referring to a category of people differentiated from the social majority that is those who have the majority of positions of social power in a society”. This paper defines minority groups as a small proportion of the population that is unique from the majority in terms of race, religion, language or gender. In this paper, minority groups in Zimbabwe will be taken to include; the Ndebele, the Kalanga, Tonga, Shangaan, Venda, whites, women, the elderly, children and Persons with disabilities (PWDs). The Shona will be taken to be the majority as they constitute 75% of the total population. World Population Review (2019), as shown on Figure 1 in the paper.

There is quite a plethora of definitions of human rights that have been used in the modern World. The United Nations defined human rights as “Those rights which are inherent in our state of nature and without which we cannot live as human beings”. This shows that human rights are quite crucial for human beings. According to (p. 34) “Human rights constitute those rights which one has precisely because of being human.” It is quite significant to observe that the element of human dignity is common in most definitions of human rights. This paper defines human rights as the inalienable and dignity rights of all members of human beings.

In this paper, minority rights can simply be defined as the normal individual rights suitable for minorities and minority groups. To that end, (p. 16) posit that “Minority rights are the normal individual rights as applied to members of racial, ethnic, class, religious, linguistic or sexual in minorities, and also the collective rights accorded to minority groups.” Minority rights are also basic and important as other rights. This paper is divided into three sections.

➢ The first part of the paper deals with minority rights in international law.

➢ The second part looks at the role of states in promoting and protecting minority rights and

➢ The third part gives a detailed analysis of the strategies and mechanisms to promote and protect minority rights in Zimbabwe.

Methodology

A mixed method approach was used in which both quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analysed. Information was obtained from textbooks, journal articles, and newspapers and published manuscripts. Text analysis was adopted to get meaning from the data obtained. The major objective was to obtain accurate information on the situation on the ground on the integration of peace, human rights and development. Mixing qualitative and quantitative methodologies in this research maybe important. However, qualitative data has been observed to universalize assumptions about the measurement of violence, war and other variables. It may also promote conclusions to be made without necessarily getting into the field (armchair empiricism).

Results and Discussion

Minority rights and International law

Recognition and existence: Minority groups need recognition that they do exist by both governments and the majority groups. There is dire need to protect their physical existence for the realization of social justice. There is need for society to exercise tolerance to diversity in order to promote the survival of minorities [4]. This in accordance with international law and statutes. There is a danger that if minority groups are not recognized, they may become extinct. To that end, the (p. 14) noted that “Promoting and protecting their identity prevents assimilation and the loss of their culture, religions and languages.” Recognition of minority groups therefore becomes a cornerstone for their survival and enjoyment of their rights. Furthermore, the right to physical existence of minorities has to be protected. It has been observed that minority groups are the most affected in times of warfare for example massacre. In view of the foregoing, Annan cited in the United Nations noted that “We must protect especially the rights of minorities, since they are genocide’s most frequent targets.” It is quite significant to safeguard the lives of minorities in times of war and peace. This is also contained in international treaties as enunciated in the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities (UNDM, 1992) which noted that states “Shall protect the existence…of minorities within their respective territories.” One can observe that it is the duty of states to protect minorities in their own territories so that they enjoy their full rights and be prevented from assimilation and ultimately extinction. Lennox pointed out that “Human rights standards require states to not merely tolerate diversity, but to cultivate diversity and respect for minorities.” States therefore have to actively promote and respect the rights of minorities. The right holders are the minority groups who have the right to be protected under international law. It could be argued that the UNDM is inclusive to a greater extent as it advocates for the respect and promotion of minority rights within states. It is crucial to observe that this is the dejure, but may not be the defacto in most countries. There is a wide gap in most countries especially in Africa between what exists at law and what is in practice. To that end, (p. 17) examines that “Therefore, international society lacks an obligatory, comprehensive, legal, minority-specific document.” Wherefore, it is quite clear that there is no legal instrument that forces states to protect the rights of minorities. There is however, need for states to promote the promotion, fulfillment and respect for minority rights.

Non-discrimination and equality: The right to non-discrimination of minorities is contained in the International Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). The treaty is inclusive to a greater extent as it protects individuals against all forms of discrimination. This is the basis of the promotion of minority rights as international law and statutes. The 2007 Durban Declaration further strengthens this when it affirms that “The ethics, cultural, linguistic and religious identity of minorities, where they exist, must be protected and that persons belonging to minorities should be treated equally and enjoy their human rights and fundamental freedoms without discrimination of any kind.” It is therefore quite crucial to note that minorities have a claim to the right to non-discrimination. In that vein, minorities are the right holders who have a right to non-discrimination in this treaty. The states are the duty bearers who have a duty to ensure that minorities are protected. The core interest of the treaty is the minority groups who have to be protected against discrimination.

Participation and inclusivity: Minority groups have a right to active involvement and participation in all aspects of life for them to benefit from a country’s development prospects. Participation is well articulated by most civil rights movements for example Global women’s rights who advocate for the fulfilment and realization of individual rights despite membership to a minority or majority group. It could be argued that participation in all public affairs of the state and in political, social, cultural and economic affairs helps to promote social inclusion and preserves the identity of minorities. This is in tandem with international law and conventions on promoting and protecting minority rights. The International Covenant on Economic, social and cultural rights (CESRC) provides that citizens have to fully participate in the economic, social and cultural life in their specific countries. There is need for states to craft inclusive policies that cater for all groups in society. Policies of exclusion may lead to loss of citizenship by minority groups leading to stateless persons. This would be a violation of international law and statutes which protect minorities against statelessness. The 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, article 9 clearly states that “a contracting state may not deprive any person or group of persons of their nationality on racial, ethnic, religious or political grounds.” The core interest of the convention is to protect minority groups from losing their citizenship on the grounds of being in the minority. The discrimination prevents minorities from enjoying their full rights to citizenship as provided for in international law. Minority groups are the right holders in this convention who have a claim to protection from the state. The state therefore is the duty bearer with a mandate to ensure that minority rights are protected in line with international law and conventions.

Government’s Role

The constitution and equality

Background: Zimbabwe had been using the Lancaster house constitution since her independence from colonial rule. The constitution had 19 constitutional amendments which is clear sign that it had become a necessity to craft a new constitution. Therefore, the Lancaster house constitution was no longer in abreast with modern legal trends.

For the purposes of this discussion, no much attention will be paid to the whites as a minority group since they enjoyed a lot of privileges before and after independence such as preferential access to resources for example prime and large tracts of land, minerals and a system of governance which was favorable to their needs. Therefore, efforts to respect, protect and promote minority rights could not be directed towards an already privileged group. In the analysis of the Zimbabwean context minority groups will be taken to include the Venda, the Ndebele, Tsonga, Shangaan and other groups except the Shona who make up 75% of the total population and hence are the majority. It could therefore be argued that efforts to respect, promote and protect minority rights by the Zimbabwe government should be justifiably directed to these ethnic groups shown on the diagram below, in addition to the elderly, women, Children and Persons with Disabilities (PWDs). Figure 1 below clearly illustrates this distribution.

The government of Zimbabwe has implemented a number of mechanisms and strategies to promote and protect minority rights. By adopting the principle of constitutional supremacy in the 2013 constitution, the government made it clear that protection and promotion of minority rights is paramount. Constitutional supremacy means that the constitution supersedes all customs and practices that violated the rights of minorities [5]. It could be argued that the Lancaster house constitution was silent on the rights of women and hence indirectly promoted their marginalization. In view of the foregoing, (p. 72) examines that “The 2013 constitution clearly espouses values and principles of gender equality, as opposed to the Lancaster house constitution that allowed discrimination.” One can therefore posit that the 2013 constitution aims to promote principles of equality and non-discrimination. The government of Zimbabwe, as the duty bearer deliberately adopted a constitution that targeted women to promote equality. The government of Zimbabwe went further to align the constitution with a domestic law by crafting the Domestic Violence Act (5.18). This was a significant step towards promoting gender equality and Zimbabwe has been hailed for that move. In that vein, (p. 72) in reference to the Act, posit that “Zimbabwe was then one of six Southern African countries to have such specific legislation on domestic violence.” It is crucial to observe that historically, women in Zimbabwe in particular and in Africa and the World in general, have been marginalized and hence socially disadvantaged. The enactment of such pieces of legislation in a greater way have helped to reduce the wide gap between men and women. This is in tandem with international law and practice aimed to promote and protect minority rights. Notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex. The core interest of these pieces of legislation is the protection of women. The state is the duty bearer which is obligated to ensure the protection and promotion of the rights of women. The right holders are the women who have a claim to demand their rights to protection, promotion and fulfilment. The government of Zimbabwe appointed the Gender commission as an implementing organ to promote and protect the rights of women in Zimbabwe. The commission collects data through research, provides feedback to government and provides recommendations. It therefore acts as a monitoring mechanism to check on the progress of government on the promotion of gender equality. The Zimbabwe government therefore has put in place mechanisms and strategies to protect and promote the rights of minorities.

However, it is prudent to note that such pieces of legislation only exist at policy level and hence there is a gap between what is at law and what is in practice. This is due to lack of awareness of the abovementioned pieces of legislation by the majority of the right holders especially women in remote parts of the country. Perception is also another crucial factor as women and society would be more worried about first generation of rights such as availability of food than second generation of rights. Questions on the effective mechanisms and strategies to create awareness and change of perception therefore become pertinent. Furthermore, even where perception levels are quite high, the full enjoyment of the said rights may be hampered by cultural practices. In the event of domestic violence for example, some cases have been withdrawn because the man as the breadwinner could not be incarcerated as they may be serious consequences for the family. The wife is ‘forced’ to withdraw as close family members may team up against her for it is taboo to send your husband to jail and risk total collapse of the marriage union because of common assault.

The constitution and women participation

The government of Zimbabwe crafted the 2013 constitution which made significant strides in promoting and protecting the rights of minorities for example women as earlier on alluded to in the paper. The constitution advocates for gender balance in all institutions and agencies of government [6]. The constitution of Zimbabwe (2013). It is crucial to point out that section 3(g) of the said constitution articulates that “Gender equality is one of the values of Zimbabwe.” This is quite a remarkable development as it as a step further than the Lancaster house

constitution which totally ignored the issue of women. The promotion and protection of women was further enunciated in section 56 (1) of the 2013 constitution which provides that “All people are equal before the law and have the right to equal protection and benefit of the law [7].” The constitution is quite clear as a mechanism to promote equality between men and women by eliminating all forms of discrimination against women. This resonates well with the provisions of international law and statutes. The Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) is an international piece of legislation which provides for the achievement of women’s equality with men. The core interest of the convention is to safeguard women against exclusionary and discriminatory policies. To further strengthen its efforts, the government of Zimbabwe has developed the concept of affirmative action whereby the entry points of female students in certain programs at University level for example law, which were seen as male dominated, are lower than those of males. The strategy is aimed at redressing an imbalance in those professions which were dominated by men. In addition, the government of Zimbabwe has implemented the quota system in political posts, where some seats are reserved for female candidates to be in the legislature. The idea again is to reduce male domination and for these female members of parliament to influence policy and hence promote the enactment of pieces of legislation that help to achieve equality between men and women.

It is important to observe that section 17 (1) (a) of the 2013 constitution provides that the “state must promote full gender balance in society.” This is a milestone in the domestication of international law for the promotion of gender equality which was absent in the Lancaster house constitution. Added to that, is an enforcement mechanism in section 85 which provides a chance for one to seek compensation or redress if one feels a basic right was infringed. One can therefore posit that there is the availability of a redress mechanism which is provided for in the constitution and hence the mechanisms and strategies for promoting and protecting minority rights are clearly spelt out in the 2013 constitution.

However, it is crucial to note that this is what exists at law and may not be what exists in practice. It could be argued that the constitution is clear at policy level and its provisions have not benefited the majority of the right holders. This is due to the fact that very few minority groups are aware of the constitutional provisions of the document. This is evidenced by the prevalence of violations along gender in practice and other forms of abuses related to sex orientation which have not been brought for redress or compensation. This could be attributed to issues of awareness as earlier on alluded to in the paper or it could have something to do with impunity where some members of society are ‘untouchables’ due to their political affiliation or positions in society. In addition, the quota system has raised some contestations as it seems to violate the basic tenets and principles of democracy which advocate for perfect competition in the electoral field. This therefore renders the implementation mechanisms and strategies weak and resultantly ineffective.

The constitution and Persons with Disabilities

People with disabilities are minorities whose rights need to be protected, promoted and respected. It is crucial at this stage to note that the 1979 constitution only recognised physical disability by simply mentioning that it must not be discriminated against. According to (p. 87), the author observed that “The 1979 constitution scantly mentioned disability under section 23(2).” Though it condemned discrimination, it only recognized physical disability to the exclusion of all other forms of disability. Persons with disability (PWDs) have been observed to be marginalized the World over. To that end, Moyo (p.87) examines that “In every region of the World, persons with disabilities often live on the margins of society deprived of the most basic human rights and fundamental freedoms.” This is clear evidence that Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) face discrimination and hence there is need to protect, promote and respect their rights. This is in tandem with the Convention on the Right of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), article 1 whose major provision “Is to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all PWDs and to promote respect for their inherent dignity.” The core interest of the convention therefore is to promote the plight of PWDs so that they enjoy their rights as minorities. The right holders are the Persons with Disabilities who have a claim to have their rights respected, promoted and protected. The state is the duty bearer with an obligation to ensure that the rights of minorities are protected and promoted. In line with international law, the Zimbabwe government passed the 2013 constitution which recognizes the rights of PWDs at different levels. This is quite a remarkable development for a country that previously did not protect the rights of PWDs. Section 120(1)(d) of the 2013 constitution of Zimbabwe provides for the appointment of two elected senators nominated by PWDs to champion their cause.

In Zimbabwe women with disabilities have been observed to suffer from exclusionary policies and hence their rights need to be protected, promoted and respected. In that regard, Moyo argued that “Poverty, misery, illiteracy, joblessness and racial exclusion are some of the common plights that women with disabilities face in Zimbabwe [8].” It could be argued that disabled women suffer discrimination as women and discrimination as disabled persons as well. The crafting of the 2013 constitution of Zimbabwe has been regarded as a huge development in that it expanded disability rights in the country.

However, it is crucial to observe that this only exists at policy level and is not what happens on the ground. One can safely observe that the constitution provides for the promotion, protection and fulfilment of disability rights but the implementation strategies and mechanisms are weak. In addition, the institutions which are there to enforce the promotion of these rights do not have the requisite knowledge and skills to effectively complete this task. The police for example, do not have adequately trained personnel to identify invisible disability and can only identify visible disability. There is therefore a knowledge and skills gap which hampers the full enjoyment of rights of Persons with disabilities. Minority rights and languages

The Lancaster house constitution only recognised Shona, English and Ndebele as the official languages in Zimbabwe. This means that for the past 36 years after independence, minority groups such as the Venda, Tsonga, Shangaan and others have been deprived of their right to language. Their languages were not included in the school curriculum and students from these groups were thus forced to learn other languages. This was a gross violation of their basic human right to learn in their own language and therefore this needed redress. It was after the 2013 constitution and the introduction of the new curriculum that we saw the introduction of the teaching of other minority languages in schools such as Venda, Chewa, Tonga and others. Section 6(1) of the 2013 constitution noted that “The following languages namely Chewa, Chibarwe, English, Kalanga, Koisan, Nambya, Ndau, Ndebele, Shangani, Shona, Sign language, Sotho, Tsonga, Tswana, Venda and Xhosa, are the officially recognized languages of Zimbabwe.” The non-recognition of minority languages was a violation of the rights to speak or learn in their own language which has been violated since independence. One can therefore conclude that these minority groups have never fully enjoyed independence up until the crafting of the 2013 constitution. Interestingly, a closer look of those official languages reveals that Kore kore and Budya languages are not mentioned. It can be subsumed that they are under Shona, which may not be the case and if so, they run the risk of being assimilated and hence becoming extinct due to non-recognition.

Section 63 (a) of the 2013 constitution provides that “Every person has the right to use the language of their choice.” The government of Zimbabwe made an important decision to cater for minority languages and include them in the curriculum. It is now mandatory that students learn two official languages and this has seen some languages being introduced in areas that previously did not speak such languages. Teachers have been trained at colleges and universities to teach some of the minority languages that were introduced at primary school level. This can be regarded as an important development towards the protection, promotion and fulfilment of minority rights.

However, though this is quite a noble policy, it remains to be seen if the superiority attached to English at the expense of local languages will cease to exist. That remains a great challenge given that the so-called elite schools emphasize the use of English and shun local languages. In addition, all subjects except Shona are examined in English at national examinations. At Advanced level, even Shona as a subject is examined in English. It is quite significant to point out that there is a serious change of mind set and a policy shift required for the full enjoyment of the of use minority languages. It could be argued therefore that though the government made significant efforts to promote minority languages by enacting a well-meaning constitution, there are no institutions to enforce this which hampers the success of mechanisms and strategies to promote and protect minority rights.

The constitution and child rights

The raising of children properly in tandem with modern trends and international dictates has raised mixed reactions in most societies. Though cultural aspects need to be taken into consideration, generally there has been a shift from the historical perspective which viewed children as objects of parental care. Appiagyei-Atua (2012). The United Nations Convention on the rights of the Child (CRC) is an international treaty which is all-inclusive on these rights. The treaty defines children in article 1 as “every human being below the age of eighteen years, unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.” This definition is quite significant to make sure schools and communities protect children and hence prevent abuse. Children also get inspiration to speak against abuse and infringement of their rights. The core interest of the convention is the child whose safety must be protected and promoted by putting the interest of the child first before everything else. The child is therefore the right holder who has a claim to that right. The state is the duty bearer with a mandate to ensure that the rights of the child are respected, promoted and protected. A regional law was drawn from the international law known as the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC) adopted in 1990 as a regional treaty. It is crucial to argue that Africa as a continent made an important decision to craft a charter in line with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). The charter provides for the respect of the status of children. It is of great importance at this point to posit that the Lancaster house conference safeguarded oppressive customary laws that violated children’s rights. In contrast, the 2013 constitution of Zimbabwe promoted the contribution, protection and independence of children. In tandem with international law and best practice, the Zimbabwe government enacted the Children’s Protection and Adoption Act (CPAA) which provides for the protection of children. The act prohibits the exposure of children to hazardous and harmful conditions. Furthermore, the 2013 constitution of Zimbabwe protects children from child marriages. Section 19 (1) of the 2013 constitution of Zimbabwe provides that “The state must adopt policies and measures to ensure that in matters relating to children, the best interests of the children concerned are paramount.” It is quite notable to observe that at policy level, the government of Zimbabwe has clearly laid out pieces of legislation to protect and promote the rights of children. This is a commendable effort which has made the 2013 constitution a hailed document.

It is crucial to observe that contestations have arisen on the concept of child labour as defined by these pieces of legislation. In accordance with international law, a child is not supposed to be exposed to exploitative labour practices. Legally, that would include the work that children do in the fields for no payment at their homes and any other work like the work and earn type of work. The work and earn is a popular concept in most African states in general and in Zimbabwe in particular. Children have been able to go to school by paying fees through the work and earn concept. Such students managed to complete their education which would not have been possible without engaging in ‘child labour’ because of the humble backgrounds they come from. The big question is, would this be regarded as child labour? Certainly not, in the perspective of the writer. It could be argued that earn and learn has greatly helped to improve the living standards of most children in Africa. There is therefore need to understand the cultural context in which these practices are done so as to be able to make a sound judgement on whether it is child labour or not.

However, the success of the Children’s Protection and Adoption Act (CPAA) has been seriously dented by high staff turnover among court officials and police officers with skills related to children. Furthermore, the marriage act section 22 allows girls to be married at the age of 16 years [9]. This has resulted in rampant abuse of girls resulting in forced marriages. In view of the foregoing, it is quite clear that there is need for realignment of these laws with the constitution. It could therefore be argued that efforts to protect and promote child rights have been dampened by weak law. Consequently, such loopholes have greatly hampered the success of mechanisms to protect and promote minority rights in Zimbabwe. It has been proffered that minorities just enjoy two rights in international law that is, the right to live and the right to identity. There is therefore still a long way to go to promote and protect minority rights.

The constitution and rights of the elderly

The elderly in society are part of minority groups that need protection from states. This resonates well with international law and best practice. The International Rights of Older persons and the International human rights status of elderly persons are international conventions aimed to prohibit age-based discrimination and promote the right to social security of the old aged people. The right holders to these conventions are the elderly who have a claim to social security and protection against discrimination. The core interest is the old aged people who have to be protected to enjoy social security. States are the duty bearers who have a mandate to ensure that old aged citizens enjoy their rights to protection and social security fully. At policy level these are quite crucial and noble pieces of legislation. In line with these international conventions, a regional piece of legislation was adopted known as the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s rights on the rights of older persons in Africa. In addition, the Kigali Declaration on Human rights in 2003, paragraph 20 “Calls upon states parties to develop a protocol on the protection of the rights of the elderly and persons with disabilities [10].” These regional and international laws are clearly laid down and their importance cannot be downplayed. They are quite significant pieces of legislation which help to make states accountable for their actions in protecting the elderly.

The Zimbabwe government enacted the 2013 constitution to respect, promote and protect minority rights. Article 21(1) of the 2013 constitution provides that “The state and all its institutions and agencies of government at every level must take reasonable measures, including legislative measures, to secure respect, support and protection for elderly persons and to enable them to participate in the life of their communities.” This is quite a remarkable piece of legislation aimed at protecting and promoting the rights of the elderly.

However, this is what exists at policy level and there is a wide gap between what is on paper and what happens on the ground. The elderly in Zimbabwe are not enjoying their rights to the fullest as their pension savings have been completely eroded and their monthly payments cannot sustain them. They therefore do not enjoy any social security under such difficult circumstances. In addition, there are weak enforcement mechanisms to force states to meet their obligations. The state has thus completely failed to meet its mandate to ensure elderly persons participate in the life of their communities.

Conclusion

This paper has tried to sketch out the most relevant dimensions of minority rights and non-discrimination for minority rights protection and promotion in Zimbabwe. The paper also tried to analyse the extent to which the mechanisms and strategies to promote and protect minority rights in Zimbabwe can be enhanced and improved for efficacy and realignment with domestic and international protocols and best practice. I would like to argue that in the light of all the evidence presented above, there are quite a number of strategies and mechanisms implemented by the Zimbabwe government to promote and protect minority rights. Though this effort can be hailed, there is need to develop institutions and effective platforms for sharing and collaboration to make them more effective and bear fruit. There is also need to involve the minority groups to be active participants in the conversation to improve the promotion and protection of their rights. It is therefore quite evident that there is need to promote, protect and fulfil the rights of minorities for the realization of social justice and continuity of these minority groups.

Acknowledgement

I am extremely grateful to the College of Business, Peace, Leadership and Governance at Africa University which supported this research, in particular I thank Pamela Machakanja, Solomon Mungure, James Tsabora and members of the college who provided useful guidance. I also thank members in my Ph.D. class who provided encouragement.

References

- Mihandoost F (2016) The Rights of Minorities in International Law. J Law Politics Semnan, Iran 9: 15-19.

- United Nations (2010) Minority Rights: International Standards and Guidance for Implementation. Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner New York UN: 2-54.

- Appiagyei-Atua K (2012) Minority rights, democracy and development: The African experience. Afr Hum Rights Law J Ghana 12: 69-89.

- Lennox C (2018) Human Rights, Minority Rights, Non-Discrimination and Pluralism: A Mapping study of Intersections for Practitioners. GCP London UK: 1-44.

- Moyo A (Eds) (2019) Selected Aspects Of The 2013 Zimbabwean Constitution And The Declaration Of Rights. RWI Sverige Sweden Europe: 1-295.

- https://zimlii.org/zw/legislation/act/2013/amendment-no-20-constitution-zimbabwe

- Lusky L (1942) Minority Rights And The Public Intrerest. Yale Law J United States 52:1-41.

- Pramod M (2001) Human Rights Global Issues. Kalpaz Publications Delhi India:1- 480.

Citation: Chitengu BM (2021) The Strategies and Mechanisms for Effective Promotion of Minority Rights to Minimize Conflict in Zimbabwe. J Civil Legal Sci 10: 283. DOI: 10.4172/2169-0170.1000283

Copyright: © 2021 Chitengu BM. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3843

- [From(publication date): 0-2021 - Apr 29, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3105

- PDF downloads: 738