Research Article Open Access

The Psychology of the Bullying Phenomenon in Three Jamaican Public Primary Schools: A Need for a Public Health Trust

Angela Hudson-Davis1, Paul Andrew Bourne2*, Charlene Sharpe-Pryce3, Cynthia Francis4, Ikhalfani Solan5, Dadria Lewis3, Olive Watson-Coleman6, Jodi-Ann Blake2, Carmen Donegon7

2Socio-Medical Research Institute, Jamaica

3Northern Caribbean University, Mandeville, Jamaica

4University of Technology, Jamaica

5South Carolina State University, USA

6Southern Connecticut State University, USA

7Cedar Valley Primary and Junior High School, Jamaica

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

Background: The bullying phenomenon, an aspect of aggression, has gained attention in many countries thus making it a very important issue in schools. Many studies have been done on this issue resulting in deeper analysis and review on the matter because the matter covers physical, verbal or psychological acts of aggression that may be intentional, and, which may occur once or repeated over time. Objectives: This study seeks to examine the following research questions: 1) How is bullying manifested in grades 4-6 in primary schools identified for this study?; 2) What are the specific bullying behaviours exhibited by class bullies in grades 4-6?; 3) How does the behavior of bullies affect the conduct of classes?; 4) What are the characteristics of the students who are targeted by in-class bullies?, and 5) What strategies are currently used by the teachers to deal with bullying in class? Materials and Methods: Two hundred students were conveniently identified (n = 200) for the study in the three schools of which 153 participated in the survey (i.e., response rate of 76.5%). The sample comprises of pupils in grades 4, 5 and 6, which 67 pupils in grades 4 and 5, and 66 in the 6th grade. Likewise 50 students ages 9, 10, 11 and 12 years were recruited for participation, with the least respondents being ages 9 years (46%) and the most being 11 years old (94%). Results: The principals and guidance counselor reported that the bullying phenomenon is a daily occurrence at their schools and that on a daily basis they are called upon to address at least 3 cases and a maximum of 10 cases of bullying. All the parents in this study noted that the bullying phenomenon is widespread in primary schools in St. Thomas and that schools are now considered an unsafe environment. Of the 26 surveyed parents in this research, 92.3% indicated that ?schools are no longer fun for children to be anymore because of the bullying phenomenon. Conclusion: Now there is empirical evidence that the bullying phenomenon is creating psychological issues that extend beyond the aggressor to those around him/her. The psychology of the bullying phenomenon is far-reaching more than a social issue and as such clearly the psychology of the matter is crying out for public health efforts and/or intervention in Jamaica.

Keywords

Bullying, psychology of bullying, children in schools

Background

One of the worldwide issues in education is the alarming rate and nature of school violence and aggression. Overtime this has escalated into murders and perpetrators are becoming more belligerent in their behaviours and are finding more ingenious ways to commit their acts. Interests have been raised in this field of research since the first studies relating to school aggression was carried out in the late seventies in Norway by Dr. Dan Olweus, a Swedish researcher (Estivez, Murgui, & Musiti, 2009). The bullying phenomenon, an aspect of aggression, has gained attention in many countries thus making it a very important issue in schools. Many studies have been done on this issue resulting in deeper analysis and review on the matter (Duncan, 2006; WHO, 2010; Donegan, 2012; Mishna, 2012) because the matter covers physical, verbal or psychological acts of aggression that may be intentional, and, which may occur once or repeated over time (Mishna, 2012). Rightly so in the Caribbean, particularly Jamaica, the bullying phenomenon is studied because of alarming rates of violent crimes caused by young people, especially murders certainly if they are in schools.

In the examination of two decades of research on bullying in schools; Smith and Brain (2000) make mention of pioneering places such as Norway, Finland, Ireland, Japan, England, Scotland and Wales. New studies focused on bullying in the 90s have been spearheaded by Germany, Spain, Switzerland, France and North America among other nations. Researchers such as Crick & Dodge (1994); Ross (1996); Alaska & Bruner (1999), and Byrne (1999) have explored various aspects of bullying and its negative effects on children. The intensity of research in this area is not as forthright in the Caribbean and more so in Jamaica, particularly from a public health perspective.

The psychology of the bulling phenomenon and its influence are intrepreted as a public health phenomenon in Jamaica. Young people are influenced by the negative attitudes and behaviors in society. The adult psychology of crime is influence in-class psychology at the primary level and beyond. A cross-sectional probability survey by Powell, Bourne and Waller (2007) found that crime and violence is atop the list of national problems in Jamaica, indicating a culture of social conflict, violence and viciousness in the society, which would have fashioned behaviours of young people. Berk (2010), states that this culture “shapes family interaction and community setting beyond the home” and need to be considered in relation to others. In our context, these behaviours are practiced in the wider home communities and are extended to the schools where children spend most of their waking hours.

Some things seem to be accepted naturally and as the undesirable behaviours surfaced; a blind eye is usually turned to many of the atrocities and an acceptance mode comes into focus. On the other hand, some people do not accept things for what they are and prefer either to ignore it, make the wrong diagnosis or apply inappropriate treatment to undesirable aggressive behaviours; bullying being one of them. Representing the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) at a seminar on homophobic bullying and violence in schools, held at the Mona Visitors’ Lodge at the University of the West Indies on May 17, 2012; Robert Fuderich reiterated that, “Every child has a right to learn in an environment that is free from harassment and violence, whether it is perpetrated by teachers or peers.” He further noted that in instances like these the child’s right, education, health, self-expression and involvement in activities are compromised.

Bullying has been identified as the main cause of school aggression and violence (Olweus, 1999). Although this is identified in so many countries; and even though Jamaican schools are being plagued with violent acts among children and a wide display of aggressive behaviours; bullying is usually not cited as a key factor in public health of this increasing phenomenon, hence this study. In addition to this, it is to raise our level of awareness of this phenomenon, and strategize accordingly in order to find answers and solutions, which will ultimately positively impact in-class psychological behaviours of students. The level of students targeted was selected because of their age range; (nine to twelve years). This a sensitive age where pupils are being prepared for the Grade Four Literacy Test (GFLT) and the Grade Six Achievement Test (GSAT), subsequently they will exit the system to the secondary level.

In the Jamaican context bullying is not taken seriously by the stakeholders in the educational system, especially public health practitioners or policy maker. This may be so because our culture includes name calling and the labeling of others as a ‘sissies’ and informers if they complained that others have hurt them. One must always be seen as strong and maintains a ‘macho’ image (especially if it is a male). The situation also exists where most parents do not communicate with their children and have limited involvement in their school life. According to Tremblay (2000), the lack of parental supervision and violence at home and in communities also help to promote violence in our children who ultimately takes this violence and aggression to schools. The psychology of the bullying phenomenon has its roots in wider society.

When students’ performance is being discussed; one of the major issues is that the children are not performing at the expected level. This may be due to their inattentiveness, too many out of class concerns or a number of other issues that are causing these problems; but no emphasis is placed on the psychology of the bullying phenomenon in school. A number of endangering signs exhibit themselves, so the great concern is when these issues are glossed over or taken lightly and therefore; have far reaching effects. When this is done it alters the classroom climate and there are instances where some children do not attend school as regularly as they should because of fear of being bulled (Schwartz, 2000), hence; they do not achieve as they ought to. This study seeks to examine the following research questions: 1) How is bullying manifested in grades 4-6 in primary schools identified for this study?; 2) What are the specific bullying behaviours exhibited by class bullies in grades 4-6?; 3) How does the behavior of bullies affect the conduct of classes?; 4) What are the characteristics of the students who are targeted by in-class bullies?, and 5) What strategies are currently used by the teachers to deal with bullying in class?

Materials and Methods

Interestingly the crime statistics in Jamaica are featured in the geographical areas as well as socio-demographic characteristics, and in seeking to understanding and address the crime panademic the matter must be examined from an area perspective (Statistics department, Jamaica Constabulary Force, 1970-2014). Over the last decades, statistics from the police show that violent crimes are mostly committed Kingston and Saint Andrew, Saint James, Saint Catherine, Clarendon and Saint Thomas. Of the previously mentioned five parishes in Jamaica, which is a sub-set of the 14 parishes that constitute the island. Saint Thomas is historically known for civil unrest, murders, physical confrontations and revolts which dates back to the time of slavery. The parish of St. Thomas continues to grapple with social deviance including violent crimes and murders, has spread to the school system.

On examining educational literature for the parish of St. Thomas, no study emerges that evaluates the impact of adult crimes in the communities as well as the homes and their influence on social deviances among children including bullyism and its later effect on violence. Over the past decade, St. Thomas has been experiencing an increase in the bullying phenomenon and violent crimes in schools and this goes to the public primary schools. With the Ministry of Education report (MoE, 2009-2013) showing that many of the public primary schools in St. Thomas have been underperforming and that the pupils are below the educational expectations, and within the context of the high degree of major crimes, the researcher chosed to examine the bullying phenomenon in public primary schools in the parish of St. Thomas.

The sample for this study is drawn from 1) public primary schools in the parish of St. Thomas, 2) children ages 9-12 years old, and 3) parents and teachers of public priamry school pupils in St. Thomas including principals and guidance counselors. Convenient sampling is used to select the sample for this study. Schools that were not willing to participate in the study was excluded from the population. Of the public primary schools (or primary schools where pupils range from ages 5+ years to 12 years) in the parish (approximately 7), 3 participated in the study and these are among the under-performing schools based performance of students on the grade 5 Numeracy and Literacy Tests and the GSAT examinations. The Principals and teachers assistance were sought to forward a copy of a structure questionnaire to each students, and a team of trained data collectors were used to collect the data from the parents as well as the students and teachers. Two hundred students were conveniently identified (n=200) for the study in the three schools of which 153 participated in the survey (i.e., response rate of 76.5%). The sample comprises of pupils in grades 4, 5 and 6, which 67 pupils in grades 4 and 5, and 66 in the 6th grade. Likewise 50 students ages 9, 10, 11 and 12 years were recruited for participation, with the least respondents being ages 9 years (46%) and the most being 11 years old (94%) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 77 | 50.3 |

| Female | 76 | 49.7 |

| Age cohort | ||

| 9 years old | 23 | 15.1 |

| 10 years old | 38 | 25.0 |

| 11 years old | 47 | 30.9 |

| 12 years old | 45 | 29.0 |

| Grade cohort | ||

| 4th grade | 47 | 31.1 |

| 5th grade | 49 | 31.8 |

| 6th grade | 57 | 37.1 |

| Family structure cohort | ||

| Single parent | 58 | 37.8 |

| Both parents | 38 | 24.5 |

| Big brother/sister | 5 | 3.03 |

| Extented family members | 40 | 26.4 |

| Other relatives | 12 | 8.0 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic Characteristics of Sampled Respondents, n = 153

A mixed methodology was used for this study – survey research and phenomenology. For the survey research a standardized questionnaire was used that contained 1) demographic characteristics, and 2) Likert scale variables. The Likert scale variables were 5 point items, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree including neutral. For the interview, a tape was used to record the interview questions and responses as well as a note taker. The purpose of the study was outlined to the parents (or guardians), their involvement was sought and willing parents or guardians who wanted their child/ ren to participate in the study were required to sign and return a consent letter.

Analysis of the survey research: The Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, Version 21.0 (SPSS Inc; Chicago, IL, USA) was used for this study. Frequencies and means are computed on the basis of sociodemographic characteristics, and other variables. For Analysis of the qualitative research: A thematic approach was used to analyse the data following the transcription of the data from words to print.

Definition of Terms

For the purpose of this study the following terms are defined.

School violence: is described as any behavior that violates a school’s educational mission or climate and constitutes actions ranging from verbal to daring and critical (Olweus, 1978).

Aggression: is any hostile, violent, confrontational behaviour or attitude that is intended to hurt or irritate others.

School bully: is a person who uses strength or power to harm or intimidate others (over a period of time) especially those who are weaker (Sampson, 2002).

Bullying: is a subtype of aggressive behaviour and involves a situation in which one or more students (the bullies) single out a child (the victim), and engage in behaviours intended to harm the child. This involves persistent perpetration and unequal distribution of power (Olweus, 1994).

A victim: is the child who suffers the atrocities of bullying.

In-class behavior: involves all the attitudes and actions that are displayed by the students in a group or classroom setting.

Performance: is the accomplishment of set tasks against prescribed standards or goals which are often set within a given time frame.

Findings

Research Question One

How is bullying manifested in grades 4-6 in primary schools identified for this study?

There is a general consensus among the students, teachers, guidance counselors, principals and parents that bullying is manifested by students through 1) physical confrontations, 2) provocations, 3) destruction of property, 4) lying, 5) extortion, 6) threats, and 7) disregarding rules and instructions. However, some additional ones brought to the discussion by principals, teachers and guidance counselors were 1) excluding others from activities, 2) stoning, and 3) sending negative text messages and pictures (cyberbullying). All the principals interviewed admitted that the bullying phenomenon, as outlined above, is present in their schools and this was sanctioned by teachers, guidance counselors and parents.

The consensus among the teachers is that bullies are usually loud and aggressive. They are spited by their counterparts if they precede them in carrying out some bullying acts that they they had planned. About half the respondents agreed that most of the bullies perform below average. They are usually inattentive because they are taken up with others. They are the source of most class disturbances. It is rare that they are ignored by their peers. When they are ignored it is done by a group rather than an individual who is more likely to experience the bully’s wrath. They are defiant and do not follow instructions willingly. They are the jokers or class clowns that initiate activities that will cause the class erupt in laughter causing disturbances.

Of the 26 parents interviewed for this research, 26.9% of them indicated that their children are bullies and 24.6% reported that their children have been bullied by another student. The principals and guidance counselor reported that the bullying phenomenon is a daily occurrence at their schools and that on a daily basis they are called upon to address at least 3 cases and a maximum of 10 cases of bullying. Furthermore, one teacher said that students “deal with incidents themselves sometimes. And that in a few instances other children take on the bullies.”

All the parents in this study noted that the bullying phenomenon is widespread in primary schools in St. Thomas and that schools are now considered an unsafe environment. Of the 26 surveyed parents in this research, 92.3% indicated that ‘schools are no longer fun for children to be anymore because of the bullying phenomenon.’

Research Question Two

What are the specific bullying behaviours exhibited by class bullies in grades 4-6?

Table 2 presents the perception of the sampled students on the extent of particular type of behaviours exhibited by bullies in class. Based on the views of the sampled students, bullying is most frequently exhibited by teasing others (66.7% at least agreed) followed by disobeying rules and instruction (65.3% at least agreed), lying (62.5% at least agreed) and extortion (59.7% at least agree).

| Typology | Rating of behaviour | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | D | SD | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Physical confrontation | 20.5 | 34.4 | 23.8 | 21.8 |

| Teasing | 40.0 | 26.7 | 14.0 | 19.2 |

| Destruction of Other property | 37.9 | 21.6 | 19.0 | 21.6 |

| Disrupt Others | 28.9 | 30.3 | 17.8 | 23.0 |

| Lying | 30.9 | 31.6 | 16.4 | 21.0 |

| Extortion | 18.8 | 40.9 | 11.4 | 28.9 |

| Threats | 32.0 | 25.2 | 13.6 | 29.3 |

| Disobeying rules and instruction | 36.0 | 29.3 | 12.7 | 22.0 |

Key: A – agree; SA – strongly agree; D – disagree and SD – strongly disagree

Table 2: Views of Sampled Students on Specific Bullying Behaviours exhibited in Class, n = 153

Table 3 present the perception of teachers on particular behaviours exhibited by bullies in class. The majority of the teachers indicated that the specific behaviours listed below were practiced by bullies in class, with only 66.6% of them believed that extortion occurred in class.

| Typology | Rating of behaviour | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | D | SD | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Physical confrontation | 33.3 | 55.6 | 0 | 11.1 |

| Teasing | 66.7 | 22.2 | 0 | 11.1 |

| Destruction of Other property | 44.4 | 44.4 | 0 | 11.1 |

| Disrupt Others | 33.3 | 55.6 | 0 | 11.1 |

| Lying | 33.3 | 55.6 | 0 | 11.1 |

| Extortion | 33.3 | 33.3 | 11.1 | 22.2 |

| Threats | 66.7 | 22.2 | 0 | 11.1 |

| Disobeying rules and instruction | 44.4 | 44.4 | 0 | 11.1 |

Key: A – agree; SA – strongly agree; D – disagree and SD – strongly disagree

Table 3: Views of sampled Teachers on Specific Bullying Behaviours exhibited in Class, n = 9

The views of teachers and students were substantially different on the typology of behaviours exhibited by bullies in class, with the exception of extortion (Table 4). Sixty-seven percent of the teachers indicated that extortion occurred in class compared to 60% of the students agreeing than extortion is an in-class phenomenon.

| Typology | Rating of behaviour | Agreement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students’ view | Teachers’ views | Students | Teachers | |||

| SA | A | SA | A | |||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Physical confrontation | 20.5 | 34.4 | 33.3 | 55.6 | 54.9 | 88.9 |

| Teasing | 40.0 | 26.7 | 66.7 | 22.2 | 66.7 | 88.9 |

| Destruction of Other property | 37.9 | 21.6 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 59.5 | 88.8 |

| Disrupt Others | 28.9 | 30.3 | 33.3 | 55.6 | 59.2 | 88.9 |

| Lying | 30.9 | 31.6 | 33.3 | 55.6 | 62.5 | 88.9 |

| Extortion | 18.8 | 40.9 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 59.7 | 66.6 |

| Threats | 32.0 | 25.2 | 66.7 | 22.2 | 57.2 | 88.9 |

| Disobeying rules and instruction | 36.0 | 29.3 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 65.3 | 88.8 |

Key: A – agree; SA – strongly agree; D – disagree and SD – strongly disagree

Table 4. Views of sampled Students and Teachers on Specific Bullying Behaviours exhibited in Class

Research Question Three

How does the behavior of bullies affect the conduct of classes?

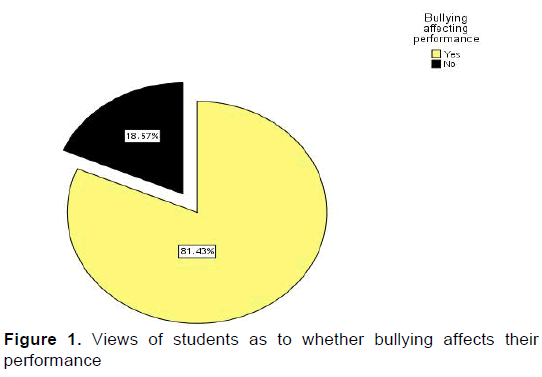

When the sampled students were asked “Does bullying affect your performance and that of your classmates?”, the majority indicated yes (81.4%) (Figure 1).

Table 5 presents the views of the sampled students on the effect of bullying on the class behaviour. Eight-five percentage points of the sampled students at least agreed that bullying increases the likelihood of some students wanting to stay away from the class; 83.1% of the students indicated that bullying behaviour lower general academic performance of students in the class and 52.7% believed that students want to see the in class bullying phenomenon.

| Typology | Rating of behaviour | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | D | SD | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Teacher do not enjoy the class | 24.2 | 25.2 | 22.8 | 27.5 |

| Unable to completed lesson | 24.2 | 31.5 | 19.5 | 24.8 |

| Lowly level of instruction | 37.3 | 26.7 | 11.3 | 24.7 |

| Children love to see the bullying | 34.7 | 18.0 | 25.3 | 22.0 |

| Some student prefer to stay away | 50.3 | 35.1 | 9.3 | 5.3 |

| Lower class performance | 62.2 | 20.9 | 4.7 | 12.2 |

Key: A – agree; SA – strongly agree; D – disagree and SD – strongly disagree

Table 5. Views of sampled Students on the Effect on Bullying Behaviour on Class, n = 153

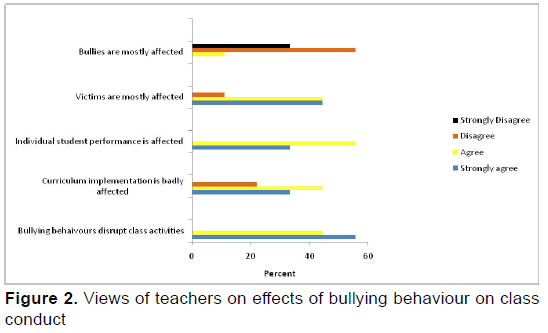

Figure 2 depicts the views of teachers on the effects of bullying behaviour on class conduct.

Fifty-five and six tenths percentages of the sampled teachers indicated that they strongly agreed with the statement that ‘bullying behaviours disrupt class activities’; 55.6% indicated that they disagreed with the statement that ‘bullies are mostly affected’ and 88.8% reported that they at least agreed with the position that ‘The victims are mostly affected’ by bullying behaviour.

In the interviews with the teachers, they indicated that the victims are usually withdrawn and do not volunteer or become involved in class activities. They indicated that the victims exhibit fear of bullies on most occasions and wait on them to endorse whether they can be involved and to what extent. Teachers usually have to intervene at this point to make it mandatory (i.e. Involvement in group work etc.). This also carries in the co-curricular activities. Victims do not readily respond to questions asked. They will participate but will not initiate responses. Sometimes they respond softly and other children have to repeat what they say. Victims are sometimes forced to share their possessions such as learning materials, food and games

Research Question Four

What are the characteristics of the students who are targeted by in-class bullies?

Generally, the characteristics forwarded by both teachers and students on bullying behaviour were equally selected, with the exception that the victims will be unhappy (Table 6). The leading characteristic identified by teachers on the victims of the bullied was withdrawal (88.8%) compared to the victims eventually becoming bullies themselves as reported by students (80.8%).

| Typology | Rating of behaviour | Agreement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students’ view | Teachers’ views | Students | Teachers | |||

| SA | A | SA | A | |||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Withdrawn | 38.7 | 32.0 | 22.2 | 66.6 | 70.7 | 88.8 |

| Refusal to make report | 36.2 | 34.2 | 11.1 | 55.6 | 70.4 | 66.7 |

| Become bullies themselves | 43.7 | 37.1 | 0 | 77.7 | 80.8 | 77.7 |

| Not enthused about school | 29.4 | 46.4 | 11.1 | 44.4 | 75.8 | 55.5 |

Key: A – agree; SA – strongly agree; D – disagree and SD – strongly disagree

Table 6. Views of sampled Students and Teachers on Characteristics of Victims of Bullying Behaviours in Class

Furthermore, the guidance counselors indicated that 9 out 10 times the victims remained victims, suggesting that there are instances when the victims become the bullied which support the findings from teachers and students.

Research Question Five

What strategies are currently used by the teachers to deal with bullying in class?

Among the students, they believed that the measured used by classroom teachers to address the bullying phenomenon include 1) stopping less and addressing behaviour (80.3%); 2) sending the perpetrator to the guidance counselor and/or the principal (90.8%) and, 3) using the appropriate referral system (72.4%) (Table 7).

| Typology | Rating of behaviour | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | D | SD | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Stop lesson and address behaviour | 45.4 | 34.9 | 8.6 | 11.2 |

| Sent to guidance counselor or principal | 57.9 | 32.9 | 3.9 | 5.3 |

| Refer to the system in place | 37.5 | 34.9 | 16.4 | 11.2 |

Key: A – agree; SA – strongly agree; D – disagree and SD – strongly disagree

Table 7. Views of sampled Students on the Measures used by Classroom Teachers to address the Bullying Phenomenon

Table 8 presents the views of teachers on the measured that they employ on seeing bullying behaviour exhibited in class. The mechanisms include 1) teacher internal approach, 2) child sent to guidance counselor and/or principal, 3) system in place to address behaviour and 4) the school has a clear policy on the bullying phenomenon. The majority of the teachers indicated that their schools do not have a clear policy on the bullying phenomenon (55.6%), while most of them choice the other measures – including the bystander role.

| Typology | Rating of behaviour | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | D | SD | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Teacher internal mechanism(s) | 22.2 | 66.7 | 11.1 | 0 |

| Sent to guidance counselor or principal | 11.1 | 55.6 | 22.2 | 11.1 |

| Refer to the system in place | 11.1 | 55.6 | 22.2 | 11.1 |

| School has clear policy on bullying | 11.1 | 33.3 | 44.4 | 11.1 |

Key: A – agree; SA – strongly agree; D – disagree and SD – strongly disagree

Table 8. Views of sampled Teachers on the Measures they use to address the Bullying Phenomenon

In the qualitative interviews with the different stakeholders (i.e. principals, guidance counselors, teachers and parents), they indicated the measures employed upon observing the bullying phenomenon included (1) speak to children, (2) Send back to teacher, (3) refer to Guidance Counsellor (4) Call parents/guardians (5) administer punishment in some cases. Those measures were the consensus of the stakeholders. The principals and guidance counselors indicated that the measures range from 50% effective to 80%, and that one in every 2 parent cooperates with the institution to address bullying behaviour exhibited by their children. On the other hand, teachers reported that sometimes they are victimized by the administration because the institution is supportive to the children who are bullies (ie. they are not suspended etc.). In addition to the aforementioned issue, principals and guidance counselor indicated that there is no clear rules and policy from a school level on the bullying phenomenon and that the Ministry of Education needs to formulate a policy on the matter.

The parents, on the other hand, indicated that about 50% of the cases are managed well by the school while the other 50% did not agree. Their justification is that if it was managed well then parents would not have to be called. They agreed that there needs to be clear cut policies and guidelines that specifically related to bullying so that there will be a clearer understanding of the procedures, consequences etc. The idea of a standard procedure would be preferred by all. This discussion came out of the present happenings at school. The parents feel that fairness is not employed where this is concerned. One punishment is meted out to one child while another with the same offence is treated differently. They feel that the policy would remedy this situation.

The parents, on the other hand, indicated that their children’s schools do not have an effective and clear policy on bullying in schools, which promote a safe school environment. When the parents were asked “There is system in place to at your child’s school to deal with bullying?’, 53.8% indicated no.

Discussion

Jamaica has been experiencing a crime problem since the 1990s. The crime problem in Jamaica has resulted in heightened fear and victimization, so much so that it is the number one leading national problem. A cross-national probability survey which was conducted by Powell, Bourne and Waller (2007) found that 11 out of every 25 Jamaicans indicated that crime and violence was the leading national problem followed by unemployment (15 in every 50 Jamaicans) and education (3 in every 50 Jamaicans). Using secondary national data on inflation, unemployment, exchange rate and murder for Jamaica, Bourne (2011) gross domestic product (GDP) and the exchange rate are strong predictors of violent crimes in Jamaica. It can be extrapolated from the crime statistics and studies on crimes in the Caribbean, particularly Jamaica (Harriott, 2003, 2004; Bourne, 2010, 2011, 2012; Bourne, Pinnock and Blake, 2012; Bourne and Solan, 2012), that there is a culture of crime in the society. This crime pandemic has infiltrated the schools so much so that there many these acts of violence committed by students have been aired more frequently and reported in the media. Like the widespread crime problem in the society, school violence is equally widespread, gruesome and frightening. The extent of acts of violence in school is, therefore, a reflection in the wider society as children learn ‘what they see’ (i.e. socialization). Schools which should be a safe and conducive environment for learn has become unsafe places (Bastian & Taylor, 1991). While many people report and are concerned about 1) rapes, 2) shootings, 3) stabbings and 4) beatings in school little attention is placed on 1) verbal threats, 2) cursing, and 3) namecalling. An extensive and comprehensive review of the literature revealed no study that has evaluated the ‘bullying phenomenon’ in the classroom at the primary level. At the primary level aggressive behaviour, including name calling and the exertion of power, occurs and this act has an influence on the social environment and by extension the educational level of students.

Studies that have examined acts of violence in schools (Bourne, 2007; Bastian & Taylor, 1991; Grumpel and Meadan, 2000; Batsche and Knoff, 1994) have not examined bullying at the primary level, particularly in class which is expanded on by this research. According to Bourne (2007), “Gumpel and Meadan (2000) further classified aggressive behaviors as either acts that are clearly violent as in the case of those inflicting bodily harm or lower level type consisting of those including teasing, bullying or name-calling” (p. 4), suggesting that the social deviance in schools must extend to primary level as bullying is a real phenomenon. The present findings found that bullying in class is a clear phenomenon occurring in primary schools in St. Thomas. Furthermore, students, teachers, guidance counselors, principals and parents in this work indicated that bullying is manifested by students through 1) physical confrontations, 2) provocations, 3) destruction of property, 4) lying, 5) extortion, 6) threats, and 7) disregarding rules and instructions, 8) excluding others from activities, 9) stoning, and 10) sending negative text messages and pictures. The literature did not highlight that the bullying phenomenon included negative text messages and pictures which emerged in this work. The aforementioned issues outlined by the different stakeholders in this research are such that the principals interviewed indicated they must address at least three cases of bullying on daily basis.

Norguera (1995 in Bourne, 2007, p. 5) noted that the occurrences of violence in school are clear indications that the administrators have loss authority in school management. Norguera’s perspective is highly simplistic and does imply that violence is a manifestation of break-down of authority as against social issues among or between people. Social deviance could be an expression of a retaliatory position of people against a social system that is oppressive, untenable and exclusionary. Another issue which is not taken into consideration by Norguera is the socialization process children are social being and if they cultured into a violent milieu there is greater probability that they are likely to exhibit the experience of the wider society. Clearly the widespread violence and criminality in Jamaica and the wider Caribbean is account for the expression of the acts of violence seen in schools including the bullying phenomenon at the primary level. While Norguera may want to ascribe who is response for the acts of violence in schools, it goes beyond the breakdown of authority. Emile Durkheim explains the crime or violence phenomenon in the society, when he contended that “Crime is needed for society to evolve and maintain itself and that there is no society that does not have crime ........” (Durkheim, 1895), suggesting that crime is expression of people.

In Jamaica, Powell, Bourne and Waller (2007) found that crime and violence were the leading national problem and that interpersonal trust was low among Jamaicans. Powell, Bourne and Waller found that 7/100 Jamaicans indicated that they trust other people, 3/25 said the ‘war against crime and delinquency in Jamaica is being won’, 9/50 people have been assaulted and attacked, 16/25 believed that the police can be bribed (Powell, Bourne and Waller, 2007), which speaks to the social dilemma which is occurring in the society and that this is affecting the children. There is no denial that the social deviance at the primary level is an indication of the cultured milieu of violence in the social, the low interpersonal trust and that these cannot be solely placed at the feet of school authority to solve the general social decay in the society. Studies have empirically established that exposure to violence causes one to commit acts of violence (Centerwall, 1992; Ascher, 1994; Widom, 1991), which offers an explanation for the bullying phenomenon at the primary level, particularly among students in St. Thomas, Jamaica.

This study found that bullies are usually loud and aggressive. They are spited by their counterparts if they precede them in carrying out some bullying acts that they wanted to do. About half the respondents agreed that most of the bullies perform below average. They are usually inattentive because they are taken up with others. They are the source of most class disturbances. Like the bullies the victims performed at a lower level, which must offer an explanation for the low performance of children at the primary level. It may be argued that this position is stretching the violence and academic performance too far, but the general violence in the society coupled with social environment at school must substantially interfere with the quality of the education received by all concerns along with the health and well-being of the victims. All the stakeholders in this research agree that the bullying phenomenon is affecting the quality of the academic performance of the bullied and the victims, which must extends to the wider class populace. The reality is, bullying means that lessons are interrupted, the psyche of the class changes from learning to something else, and the lost time places increasing pressure on the teacher to complete the already time driven syllabi.

The relationship between bullying and other acts of violence disrupts the learning process. This is directly related to the lower quality of the educational outcome that cannot be overstretched as the nature and extent of the violence must substantially retards the psyche of the child away from learning if the incidences occur at school. Among studied sample of high school students, Soyibo and Lee (2000) found that 27% of the participants had caused injuries to persons, 59.5% used weapons during violent acts, including the use of hands or feet. Some 59.1% used nasty words, 54.5% used punches and kicks, 26.5% used blunt objects, 18.4% used knives, 9.3% used ice-picks, 8.9% used machetes, 8.5% used scissors, 7.5% used forks, 6.9% used guns, other weapons (bottles and dividers) 6.7% and 5.5%. The findings of Soyibo and Lee are not limited to high schools as Callender (1996), researching schools in Kingston, Jamaica; found that 7 out of every 10 pupils had seen fights in which a weapon was used. Another research on acts of violence in Jamaican schools by Meeks-Gardener (1999) revealed that 84% of children knew the child who took weapons such as a knife to school. Furthermore, Meeks-Gardener found that 8 out of 10 children witnessed in-class confrontations and 40% of them saw teachers been attacked by pupils.

So when parents in this study indicated that ‘schools are no longer fun for children to be anymore because of the bullying phenomenon. The reality is, this translate into lower academic performance among the victims and perpetrators as well as the general class populace. Bourne (2007) many young adults indicated having experienced violence in their lives, which would be the same for young primary school aged children, if this were to be the case in schools, the young child/ren would dread the school experience. The constant psychological scar of witnessing violence in schools, in the form of threats, name calling, physical confrontation and otherwise, is making schools unsafe for pupils and retarding the learning process. The issues of not wanting to attend school by primary school children are embodied in some of the current findings 1) bullying is most frequently exhibited by teasing others (66.7% at least agreed), 2) bullies disobeying rules and instruction (65.3% at least agreed), 3) children lying (62.5% at least agreed) and 4) some students extort other (59.7% at least agree). Instead of school being that conducive place for learning, primary school students must be contemplate on the probability of being bullied by others and this reoccupation translates into 1) fear of school, 2) fear in class, 3) the mind is overly occupied with the likelihood of acts of violence by learning. The intercorrelation between acts of violence and lower academic performance was endorsed by students in this study as 81.4% indicated that bullying affects their academic performance, which is supported by the teachers, guidance counselors, principals and parents. This finding is in keeping with empirical evidence of the literature that violence inverse relate to academic performance (Gumpel & Meadan, 2000; Ascher, 1994; Batche & Knoff, 1994; Soyibo & Lee, 2000).

The number of violent acts and the nature of these acts have directly associated with the low academic performance of students in Jamaican schools. It can be extrapolated from the findings of Powell, Bourne and Waller’s cross-sectional probability survey that there is national dilemma in the educational system as they found that education is the third leading national problem in 2007 (Powell, et al, 2007). Instead of integrating all the factors that account for the dismally low performance of students at the primary and secondary level in the Jamaican educational system, the former Minister of Education (then Minister, Mr. Andrew Holness) classified many schools as ‘failing schools’ (Henry, 2011) and blame principals and teachers for the dismally low performance of students.

Of the three primary schools in St. Thomas, Jamaica, based on the results of the students, one is classified as a ‘failing school’, with the others being marginally beyond average. With the plethora of acts of violence, the extent of the cases and the low of teachinglearning hours owing to interruptions to address bullying among students, principals of schools, particularly the failing ones, are faced with the challenge of how to modernize and transform poor performing students within a cultured crime environment. Apart from the challenges of the general cultured milieu from which the students are from, there are issues such as 1) parental background (including income challenges), 2) a support system, 3) nutritional inadequacies, 4) low IQ of students and 5) deficiencies in social amenities and all these things contribute to the low performance of students; yet former Minister of Education, Mr. Andrew Holness, single out teachers and principals to bear the burden the blame for the educational deficiency among students. Such a position is highly fictitious and irresponsible as the factors influence academic performance extend beyond only teacher and/or the administrators of schools.

This study found that there is low of hours, reduced instructions, inability to complete curriculum, psychological stressors of bullying and that these are inferring with the performance of victims and bullies as well as the general populace who experienced acts of social deviance. In this work, the sampled students indicated measures used by class teachers to the bullying phenenomon include 1) stopping less and addressing behaviour (80.3%); 2) sending the perpetrator to the guidance counselor and/or the principal (90.8%) and, 3) using the appropriate referral system (72.4%). These issues accommodate for some of the reduced performance of students at the primary level and all the stakeholders in this work cited that the bullying phenomenon is retarding the quality of education at the primary level in St. Thomas, Jamaica. With the literature showing that acts of witnessed violence increases probability of perpetrating the same (Bandura, 1977; Bourne, 2007; Hawkins and Catalano, 1992), the bullying phenomenon in schools at the primary level is dramatically reducing the outcome of students as they become preoccupied with violence instead of education and what obtains in the classroom. Bourne (2007) aptly described the effects of violence this way that “Besides causing physical harm, there is the socio-psychological distress associated with violence”(p. 3), and this must account for the lowered performance displayed by students at the primary level as well as otherwise.

On witnessing acts of violence in the classroom, teachers as well as administrators cannot just arbitrarily switch the minds of the children into gear to effectively absorb instructions. There is the delayed effect of the witnessed activities, the severity of the matter and the extent to which other becomes involved that will linger on the mind of the child/ren when the teacher tries to impart the instructions. Instead of solely applying themselves to learning in class, the cultured crime milieu in Jamaica is resulting in the imitation of the acts of violence, which was outlined in Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977). Social Learning Theory posited that people can acquire aggressive behaviours by way of observation and experience, and this suggests that switching from education to acts of violence goes back to the general social milieu (see also, Bourne, 2007). With Osofsky (1991) perspective that “Exposure to violence could have significant effects on children during older development” goes to the crux of the social deviance in the society and at all levels in the educational system in Jamaica. The bullying phenomenon in primary schools in St. Thomas is an expression of the wider social dilemma in the Jamaican society and it also goes to the low performance exhibited by students that the Ministry of Education can labeled some primary-to-secondary level institutions as ‘failing schools’.

Conclusion

The social deviance affecting many primary schools in St. Thomas, which extends to Jamaica as well as secondary school, continues to be a challenge for teachers and administrators of schools to solve, while little assistance comes from the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health. The various stakeholders in the present findings indicated that the Ministry of Education is found wanting as it relates to policies to address bullying in schools, which is equally the case for the Ministry of Health. In fact, in Jamaica the bullying phenomenon is not seen as a public health issue and therefore therei s no thrust by health personnel to treat the matter with any urgency or concern. Now there is empirical evidence that the bullying phenomenon is creating psychological issues that extend beyond the aggressor to those around him/her. The psychology of the bullying phenomenon is far-reaching more than a social issue and as such clearly the psychology of the matter is crying out for public health efforts and/or intervention in Jamaica.

References

- Ascher, C. (1994).Gaining control of violence in the Schools:A view from the field. New York:Teachers College, Erick Clearinghouse on Urban Education and Washington, DC: National Education Association

- Bandura, A. (1977).Social learning theory, Englewood Cliffs.New Jersey:Prentice Hall

- Bastian, L. D., & B. M. Taylor. (1991). School Crime:national crime victimization.Survey Report.Washington, DD:Bureau of Justice Statistics

- Batche, G.M. & H.M. Knoff.(1994). Bullies and their victims:Understanding a pervasive problem in the schools.School Psychology Review, 23, 165-174

- Bourne, P.A., & Solan, I. (2012). Health, violent crimes, murder and inflation: public health phenomena. Journal ofBehavioral Health, 1(1), 59-65

- Bourne, P.A., Pinnock, C., & Blake, D.K. (2012). The Influence of Violent Crimes on Health in Jamaica: A Spurious Correlation and an Alternative Paradigm. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research [serial online], 5-12

- Bourne PA. (2012). Murder and ill-health: A health crime phenomenon. Journal ofBehavioral Health,1(2), 138-146

- Bourne, P.A. (2007). Curbing Deviant Behaviours in Secondary Schools: An Assessment of the Corrective Measures Used. Paper presented at the Caribbean Child Research Conference, UNICIF, which was titled “Promoting Child Rights Through Research”. Jamaica Conference Centre, Kingston, Jamaica, October 23-24, 2007

- Bourne, P.A. (2010). Crime, Tourism and Trust in a Developing Country. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences, 2(2), 69-83

- Bourne, P.A. (2011). Re-Visiting the Crime-and-Poverty Paradigm: An Empirical Assessment with Alternative Perspectives. Current Research Journal of Economic Theory 3(4): 99-117

- Bourne, P.A., Blake, D.K., Sharpe-Pryce, C.,& I. Solan. (2012). Murder and Politics in Jamaica: a historical quantitative analysis, 1970-2009. Asian Journal ofBusiness Management, 4(3), 233-251

- Boxill, I., Lewis, B., Russell, R., Bailey, A., Waller, L., James, C., Martin, P. & Gibbs, L. (2007). Political culture and democracy in Jamaica: 2006. Kingston: The University of the West Indies and Vanderbilt University

- Donegan, R. (2012). Bullying and Cyberbullying: History, Statistics, Law, Prevention and Analysis. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 3(1), 33-42

- Duncan, A. (2006). Bullying in American Schools: A Social-Ecological Perspective on Prevention and Intervention, edited by Dorothy L. Espelage & Susan M. Swearer. Journal of Catholic Education, 10 (2). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ce/vol10/iss2/12

- Francis, A., Elvy., L.,&Kirton, C (2001). Crime in Jamaica: A preliminary analysis. Proceedings of the Second Caribbean Conference on Crime and Criminal Justice, 14-17th February, University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica

- Gray, O. (2003). Badness-honour. In Understanding the crime in Jamaica: New challenges for public policy by Anthony Harriott. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 13-48

- Gumpel, T.P. &Meadan,H. (2000).Childrens perceptions of school – based violence.British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 391-404

- Harriott, A. (2003). Editor’s overview. In Understanding the crime in Jamaica: New challenges for public policy by Anthony Harriott. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press.

- Harriott, A. (2004). Introduction. In: Harriott, A., Brathwaite, F. & Wortley, S., eds. (2004). Crime and criminal justice in the Caribbean. Kingston: Arawak Publication

- Hawkins, J.D., & Catalano,R.R. (1992).Violence in American Schools:A New perspective, (ed).Elliott, D. S., Williams, K. R. & Hamburg, B. A.England:Cambridge University Press

- Henry, M. (2011). Education performance and failing schools. Kingston: The Gleaner. Accessed on May 26, 2013 from http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20110911/focus/focus1.html

- Mishna, F. (2012). Bullying: A Guide to Research, Intervention, and Prevention. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc, pp. 3-16

- Norguera, P.(1995). Reducing and preventing violence:An analysis of causes and an assessment of successful programs.In 1995 Wellness lectures.CA:California Wellness Foundation

- Osofsky, J.P. (1999).The impact of violence on children.Future of children, 9, 33-49

- Powell, L.A.,Bourne, P., &Waller, L. (2007).Probing Jamaica’s Political Culture, volume 1:Main Trends in the July – August 2006 Leadership and Governance Survey. Kingston, Jamaica:Centre for Leadership and Governance, Department of Government, University of the West Indies, Mona

- Robotham, D. (2003). Crime and public policy in Jamaica. In Understanding the crime in Jamaica: New challenges for public policy by Anthony Harriott. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 197-238.

- Simmonds, L.E. (2004). The problem of crime in an urban slave society: Kingston in the early nineteenth century. In Crime and criminal justice in the Caribbean, by Anthony Harriott.Kingston: Arawak Publishers, 8-34

- Soyibo, K. & M.G. Lee. (2000). Domestic and School violence among high school students in Jamaica. West Indian Medical Journal, 49, 232-236

- Stone, C. (1987). Crime and violence: Socio-political implication. In Phillips P, Wedderburn J eds. Crime and violence: Causes and solutions. Kingston: Department of Government, the University of the West Indies

- Stone, C. (1988). Crime and violence: socio political implications. In Crime and Violence: Causes and Solutions edited by P. Phillips and J. Wedderburn. Mona, Jamaica: Department of Government

- Widom, C.S. (1991).The role of placement experience in mediating the criminal consequence of early childhood victimization.American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61, 195-209.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 20241

- [From(publication date):

June-2015 - Apr 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 15298

- PDF downloads : 4943