Research Article Open Access

The Psychological Survival of a Refugee in South Africa The Impact of War and the ongoing Challenge to Survive as a Refugee in South Africa on Mental Health and Resilience

Sumaiya Mohamed*, Dominique Dix-Peek, Ashleigh Kater

The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, South Africa

- Corresponding Author:

- Sumaiya Mohamed

The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, South Africa

E-mail: smohamed@csvr.org.za

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

The issue of migration of refuges and asylum seekers is one which is an internationally relevant phenomenon. South Africa is home to a large portion of Africa’s refugees, who have been exposed to torture and war trauma. In addition to trauma in their country of origin, refugees face daily contextual stressors which reflect society’s perceptions of refugees as well as the social, economic and political milieu of South Africa. These daily contextual stressors exacerbate the psychological effects of their past trauma. The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation is a non-governmental organization that provides psychological services to torture survivors, with the aim of promoting psychosocial rehabilitation and mental wellbeing. Using information gathered on the CSVR’s centralised M&E system as well as through clinical reflections on a case study, this paper explores the complexity of providing psychosocial services to survivors of torture in contexts of continuous traumatic stress and daily stressors. The implications for therapy in such situations are explored as well as the necessity for the clinician to possess a role outside of the traditional therapeutic space and the ways in which to build on and promote resilience. Conclusions drawn indicate that an empowerment approach has the best utility in fostering resilience in refugees. In addition to this, clinicians are required to partake in various roles such as therapist, case manager and advocate for their clients. Furthermore, the contextual reality of clients is of utmost importance in conceptualising their mental wellbeing as well as therapeutic goals.

Keywords

War, refugee, mental health, resilience, South Africa

Background

South Africa is home to a vast number of refugees and asylum seekers who have not only been exposed to torture and war trauma, but who also experience continual daily contextual stressors which have a profound impact on their mental health and their resilience. This has become increasingly relevant in the global trend of migration and the necessity for psychosocial rehabilitation.

The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) is a multi-disciplinary organisation that uses its expertise in violence prevention and healing to assist people who have experienced severe violence and trauma. Starting in 1989, the CSVR offered free counselling services to victims of Apartheid violence. With the new democratic dispensation in 1994, the CSVR changed its focus to offer counselling services to victims of violence and crime, however with the increase in refugees and asylum seekers that came to South Africa from the early 2000s, the CSVR saw an increase in people from other parts of Africa who had experienced war, violence and torture in their countries of origin and come to South Africa for refuge.

Given the complexity of providing therapeutic interventions to survivors of war and trauma, while taking into account the context of continuous traumas and daily stressors, this article aims to focus on the mental wellbeing of refugees and asylum seekers residing in South Africa and, more specifically, the factors that contribute to both mental deterioration and resilience.

Introduction

Mental health refers to our emotional, psychological and social wellbeing which influences cognition, thought and behaviour. Furthermore, mental health is linked to the individual’s stress management and decision making. An individual’s mental health is developed over the individual’s lifespan and is shaped by the various experiences which they are exposed to. Good mental health may be viewed as a sense of wellbeing, confidence and self-esteem. It may reflect an individual that is able to use their abilities to reach their potential; cope with stresses of life; work productively; make meaningful contributions to their family and community; and form positive relationships. Holding that in mind, mental illness also referred to as mental disorder, impairment or psychiatric disability then implies a deterioration or inability to achieve the above, impacting on daily functioning in a negative manner. (U.S Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). There are a number of areas that may impact a person’s mental health or mental illness, some of which are mentioned in this article.

Psychological Effects of Torture

The physical sequelae of torture are well-documented and this is largely due to the visibility of physical injuries. Despite this, there are also numerous psychological effects of torture which may often be masked but also have a profound impact on the individual. The most common focus of literature in understanding the impact of torture centres around the development of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Higson- Smith, 2013; Jaranson & Quiroga, 2011), which is characterised by symptoms which fall into four clusters, namely: intrusive symptoms, avoidance symptoms, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Within the domain of Anxiety Disorders, Panic Disorder is also common, and is often associated with safety and security concerns. Panic attacks are characterised by periods of intense fear and is manifested in physical symptoms such as heart palpitations, shortness of breath, nausea, sweating, fear of death, depersonalisation and derealisation (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This is often comorbid with Agoraphobia (Higson-Smith, Mulder & Masitha, 2006). Other common disorders which are prevalent in this population include Acute Stress Disorder, Psychosis and Somatisation Disorders. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for victims of torture to develop personality disorders such as Borderline Personality Disorder and Dependent Personality Disorder, however it is unclear whether these are developed as a result of the torture or whether these personality traits developed in childhood are exacerbated by the experience of torture (Higson-Smith, Mulder & Masitha, 2006). This is largely dependent on the theory of personality adopted and the underlying assumptions of the nature of personality.

In addition to the development of these mental health disorders, other impacts on the psyche are noted and the impact on the overall mental health of these individuals is just as profound. Research done by Rasmussen, Rosenfeld, Reeves and Keller (2007) highlight that individuals who have experienced war trauma display symptoms of psychological debilitation such as confusion, memory impairment, poor concentration, poor judgement, disorientation and lack of energy. Kenny (2016) further argues that this psychological debilitation impacts on the individual’s ability to engage with their environments and relate to others. Patel (2003) also highlights the development of dependency, as individuals experience feelings of disempowerment, low self-esteem, feelings of inadequacy and confinement.

Torture evokes a deep sense of loss in victims, both in terms of internal and external loss. Moreover, Higson-Smith et al (2006), state that the experience of torture, as well as being separated from family creates a sense of loss within individuals and may lead to a type of internal displacement. Hensel-Dittman, Schauer, Ruf, Catani, Odenwald, Elbert and Neuner (2011) note that this sense of loss and displacement may be linked to their sense of identity, as they are psychologically altered in the process, sometimes to unrecognisable lengths. Hensel-Dittman et al. (2011) further highlights that the impacts of torture on identity can be noted in four domains. Firstly, the torture experience can cause the individual to act in a manner that is inconsistent with their core beliefs and values which results in discontinuity of the identity. This may induce feelings of guilt and shame The second way in which torture induces issues of loss is due to the fact that, it diminishes the victims’ ability to create trusting relationships and form attachments by causing the individual to perceive people differently (Hensel-Dittman et al. 2011). Furthermore, the torture experience damages the individual’s world view which includes beliefs regarding social order, justice and security. Ullman and Brothers (1988) also state that unconscious meanings may be deduced from the experience, in which torture may shatter the narcissistic fantasies of omnipotence that an individual maintained prior to the trauma, leading to a fragmentation of the self which can be manifested in dissociative symptoms Finally, the identity is also impacted by a change in behaviour such that pre-trauma and post-trauma behavioural patterns lack continuity and, consequently, the individual’s self-perceptions are altered (Ebert & Dyck, 2004).

Moreover, it is not uncommon for refugees to experience crises of existential meaning. Existential dilemmas are often one of the most enduring psychological reactions to torture and trauma. This is a result of the exposure to violence or dying, as well as their own near-death experiences. The purpose of existence itself is challenged by the existence of torture. Refugees often ruminate of the fleeting nature of life as well as their own existential purpose (Turner & Gorst-Unsworth, 1990). It is also not uncommon for survivor guilt to be present. This can arise due to witnessing many others who were detained at the same time being killed and thus raising questions about why the individual survived when their friends, family or fellow detainees did not survive. This further induces existential conflicts; forcing the individual to question the existence of a just world in the face of the cruelty they experienced (Turner & Gorst-Unsworth, 1990).

In addition to the psychological impact of war trauma and torture, commonly resulting in MDD and PTSD, evidence highlights that a relationship between a high allostatic load related to PTSD, is in turn related to physical impacts. Physical impacts noted by Pacella, Hruska and Delahanty (2015) include chronic musculoskeletal pain, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, obesity and cardiovascular disease. Moreover, McFarlane (2010) states that there is a clear association between chronic conditions and developing somatic symptoms to PTSD. Thus, there is potential for a pervasive disruption in an individual’s psychophysiology following exposure to trauma. Furthermore, when the body is constantly in a state of stress, an overload in the allostatic load has the capacity to disrupt an individual’s mental health (McFarlane, 2010).

The Role of Daily Stressors in Mental Deterioration

In addition to the above mentioned psychological impacts of torture and war trauma, refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa face additional contextual challenges which have the potential of adversely impacting on their mental wellbeing. Miller and Rasmussen (2010) explain that daily stressors represent proximal or immediate stressors, whereas, war trauma becomes a distal experience. Arguing that immediate stressors or daily stressors become psychologically salient for an individual and its continuous nature can lead to the erosion of coping resources (Kubaik, 2005), rendering individuals vulnerable to physical and psychological illness (Sapolsky, 2004). Christopher (2004) highlights that research on the psychophysiology of stress suggests that the human stress response is evolutionary geared to cope with exposure to acute, life threatening events. However, chronic stress exposure finds the stress response system maintaining an active status, leading to prolonged exposure to epinephrine, norepinephrine and glucocorticoids and ultimately increase risk of development of physical and psychological illness. This denotes the impact that daily stressors may have on exacerbating the psychological effects of torture.

Contextually, South Africa does not have refugee camps but a predominantly urban based refugee population. This means that basic services are not delivered to refugees as in a camp-based situation. It is assumed that refugees will get these needs met similarly to South African citizens (Palmary, 2006). This assumption is based on various legal acts that have been put in place to support refugees and asylum seekers and uphold their rights in South Africa. These Acts include: the Immigration Act and Refugees Act which serves to protect the rights of non-nationals as enshrined in the South African Constitution and Bill of Rights. These Acts articulate refugee and asylum seekers rights to administrative justice, legal protection, non-discrimination, access to social services, employment, education, and basic medical services (Onuoha, 2006). However, it has been argued that this legislation does not reflect the practical reality and, as such, these contextual stressors are still a reality. Several additional stressors are highlighted below. Research done by Onuoha (2006), Bandiera, Higson-Smith, Bantjies and Polatin (2010) and Langa (2013) highlight common contextual stressors that have been found to impact refugees and asylum seekers wellbeing in South Africa.

Xenophobia

Procter, Ilson and Ayto (1978) highlight that the word ‘xenophobia’ refers to a ‘strong dislike, hatred or fear of foreigners and strangers, that can be manifested in negative stereotypes, attitudes or perceptions, and may lead to intolerance, violence, human rights abuses or even death towards foreigners in extreme cases (Onuoha, 2006). Discrimination in the form of Xenophobia is an on-going problem in South Africa, with major xenophobic attacks taking place in 2008 and 2015, posing serious threats to refugee protection (Onuoha, 2006). It has been stated that the 2008 attacks marked the first time since the end of the Apartheid era that South African troops were deployed to stop violence in the streets (McKnight, 2008). Bandeira et al (2010) highlights that the estimated total number of refugees and asylum seekers displaced due to this attack ranged between 80,000 and 2,00,000.

On a ground level xenophobic attitudes are played out in aggressive and passive aggressive manners, both within communities and by officials. Xenophobia at a community level includes xenophobic sentiment, and xenophobic violence towards non-nationals, as well as burning and looting of shops and property. At a state level, xenophobia plays out in unequal service delivery or repressive police practices (Palmary, 2006). A study conducted by the University of the Witwatersrand (Tebogo, 2005) found that refugees found police unreliable and untrustworthy. Police have been accused of harassment, corruption and unlawful arrest toward foreign nationals (Tebogo, 2005). Thus, xenophobic attitudes by police impact on individuals seeking assistance, as they may fear further victimization (Sinclaire, 1999). Refugees and asylum seekers are also denied medical care and medication (Langa, 2013). Xenophobia affects refugees and asylum seekers rights in South Africa, impacting on their ability to access services in private and public spaces, as well as their ability to integrate into host communities and achieve a sense of belonging. Furthermore, the impact of xenophobia on the mental health of these individuals is concerning, as they are vulnerable to discrimination and abuse as a result of their circumstances and inability to pursue their rights (Onuoha, 2006).

Refugees and asylum seekers are further isolated and made vulnerable by the language barrier, which has implications on a daily basis in terms of communicating with service providers in the medical, legal and social settings to get needs met, as well as implications in connecting with locals and integrating into local communities. Onuoha (2006) argues that language plays a crucial part in building understanding, social cohesion and cultural values. This, compounded with the differential access to servicers, gives refugees and asylum seekers a sense of losing their status within society, making them feel unwanted in the country they originally thought they would find refuge in (McKnight, 2008).

Documentation

The Department of Home Affairs (DHA), is the government department responsible for the implementation of refugee policies, issuing of appropriate permits and documentation to refugees and asylum seekers to protect their rights and legalise their stay in South Africa, in line with the South African Refugee Act 130 of 1998 (Onuoha, 2006). Drawing from research done by Onuoha (2006), interviews conducted with some refugees and asylum seekers on their experiences in obtaining appropriate documentation, highlights several issues. Delays in documents being processed and received. According to the UNHCR 2015 Global trends report, South Africa has the highest number of pending claims for asylum seeker status, whereby individuals have to wait several years before they are informed if they will receive refugee status or not. 1, 096, 100 people in 2015 were awaiting decisions on their asylum seeker status, the highest number globally (UNHCR, 2015). Delays also mean that undocumented refugees and asylum seekers, live in continuous fear of being discovered by local authorities, arrested and deported (Birman et al. 2005).

Onuoha (2006) also states that in the process of documentation renewal, participants have to face long queues (where they may or may not be seen on that day) or travel to another province where the document was originally given, despite having settled in another province. Travel for documents has resulted in refugees and asylum seekers at times losing their employment, as they are absent from work for two to three days. Those who are travelling to another province and who have no money for accommodation sleep outside the DHA office or at a train or bus station, making them vulnerable to further victimisation. Security issues are faced, as people often sleep outside the DHA office to be in the queue first (Onuoha, 2006). It has also been highlighted that corruption exists amongst DHA officials, where bribes are paid for documents to be processed quicker. Reports by refugee and asylum seekers of sexual assault by DHA officials have also been noted (Onuoha, 2006).

Medical and Social Needs

Clients express difficulties in getting their medical and social needs met. Medical needs include accessing public health care services predominantly and social needs include housing, education and employment (Langa, 2013). Bandeira et al (2010) acknowledges that health and mental needs are a high priority for victims of war or armed conflict, especially those that have endured torture. Research by Higson-Smith et al (2006), which explored exiled torture survivors needs and experiences of health services in Johannesburg, South Africa, found that an inability to access health care was linked to discrimination, abuse by health personnel, being badly treated or being turned away and not receiving health services. It has further been argued that not having access to health care means impacts the physical wellbeing of torture survivors. This further impacts on client’s ability to recover and cope psychologically (Bandeira, Higson-Smith, Bantjies, & Polatin, 2010). Baird, Williams, Hearn and Amris (2016) indicate that the torture experience not only causes disability and pain, it also impacts on an individual’s psychological resources, including their psychological wellbeing and their ability to function. This compounds the overall personal and social functioning of the torture survivor.

In her analysis of intervention process notes at the CSVR, Bandeira (2013b) found that daily stressors in terms of accommodation and economic stressors played an important role in the psychological wellbeing of clients. Shelter and accommodation are of extreme concern to torture survivors living in South Africa (Higson-Smith, Mulder, & Masitha, 2006; Higson-Smith & Bro, 2010). In their report on the health needs faced by torture exiles in Johannesburg, Higson-Smith et al (2006) found that the most pressing need for many clients was shelter and accommodation. More than two thirds of torture clients were living in vulnerable circumstances, including living alone, with strangers, or in a shelter. At the CSVR, we find a number of clients also live on the streets or in churches. This impact’s on client’s safety. It further impacts on their emotional and psychological wellbeing (Bandeira, Higson-Smith, Bantjies, & Polatin, 2010). The Centre for Victims of Torture (2005) states that medical and social needs are not being met due to lack of resources in South Africa and the growing number of refugees and asylum seekers that enter the country yearly. As well as, noting that their eligibility for such services is limited, based on their documentation.

In addition, seeking employment to improve living conditions is a challenge for refugees and asylum seekers. Documentation can significantly impact on whether or not a refugee or asylum seeker will be employed. Furthermore, securing employment is difficult, as first preference is given to nationals. Moreover, xenophobic sentiments make this harder. High levels of unemployment amongst refugees and asylum seekers places them in a low socioeconomic status, in which many refugee and asylum seekers find themselves in poor living conditions (Bandeira, Higson-Smith, Bantjies, & Polatin, 2010). Clients have reported instances where two to three families would share a room. Loss in employment and corresponding income has been found to impact on the clients ability to cope with their past trauma and current stressors (Bandeira, Higson-Smith, Bantjies, & Polatin, 2010). In addition, the extended impact this has on the family structure and family breakdown is also acknowledged amongst our client group. As previous breadwinners are unable to provide for themselves or their family (Bandeira, Higson-Smith, Bantjies, & Polatin, 2010).

Thus, the daily contextual stressors highlighted above, that are faced by refugees and asylum seekers are hypothesised as impacting on their mental wellbeing. Coupled with this, the psychological impacts of their previous experiences of war trauma and torture are noted as contributing to this complex understanding of their mental health presentation that is engaged with therapeutically at the CSVR Trauma Clinic.

Resilience

Despite the traumatic experiences and daily stressors, it is noteworthy that refugees often develop resilience and adaptive coping styles. Bonanno (2004) states that resilient individuals continue to function in areas of their lives and continue to show capacity for positive effect. Further, stating that there are multiple and sometimes unexpected pathways to resilience (Bonanno, 2004). Several factors have been noted to promote resilience (Bonanno, 2004).

Personality traits of hardiness buffers exposure to extreme stress. Hardiness is characterised by being committed to finding meaningful purpose in life, belief that one has influence over their surroundings and the outcome of events (sense of agency and increase internal locus of control), and the belief that one can learn and grow from positive and negative experiences (Florain, Mikulincer & Taubman, 1995). Self enhancement, which refers to seeing oneself in a positive light can be adaptive and promote wellbeing (Bonanno, 2004). A study done among Bosnian civilians living in Sarajevo in the immediate aftermath of the Balkan civil war (Bonanno, Field, Kovacevic & Kaltman, 2002), found that self-enhancers showed better mental adjustment to their circumstances.

Repressive coping, where individuals tend to avoid unpleasant thoughts, emotions and memories (Weinberger, 1990). Positive emotion and laughter. Research, noted by Fredrickson & Levenson (1998) highlights that, positive emotion can help reduce levels of distress following aversive events by quieting or undoing negative emotion. Furthermore, social connections and gatherings are also encouraged, as they create the spaces for positive emotion and laughter to occur.

It has also been noted that the presence of a firm belief system, rooted in either faith or politics, aids refugees in managing their past and current stressors (Brune et al. 2002). The role of cultural and religious practices amongst this group of people and its usage in understanding and tolerating the circumstances in which they live is remarkable, and contributes to the resilience we see in our clients, as they find ways to endure what is unbearable (Mahmud, 2005). Resilience is also fostered through the capacity to make meaning of their situation (Schweitzer, Greenslade & Kagee, 2007). This can also be fostered through therapeutic work if it does not readily exist for the client. Another factor which promotes resilience is the support of family and the larger community (Schweitzer, Greenslade & Kagee, 2007). This sense of community is established through a shared cultural identity and acknowledgement of similar traumatic experiences. Through this, refugees can gain a sense of support from extended socials support system and this may foster resilience in dealing with the past trauma as well as the daily stressors that they face. Connectedness with others can re-humanise people who may have been dehumanized by their experiences, often experienced by those that have undergone torture (Mamud, 2005).

Therapeutic Work With Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Due to the fact that many of the refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa have been exposed to torture and war trauma, it is important to consider this in working therapeutically towards healing. Research that is done on the therapeutic work with victims of torture has highlighted two primary approaches, which locate healing in a different sphere of the individual’s life. Trauma-focussed work focuses on exposure to and works with the traumatic event, as well as clinical treatment, as a way to relieve the individual’s psychological symptoms. Conversely, psychosocial approaches focus primarily on the stress resulting from social and material conditions that are caused or exacerbated by the armed conflict or torture experienced by the individual (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010).

Furthermore, Judith Herman’s book titled, ‘Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence- from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror’ (1997), describes processes involved in working with trauma which are relevant to torture survivors and their recovery still today. Herman (1997) states that establishing safety, addressing primary needs and creating trust and stabilisation is the first phase and key to any successful intervention with survivors of torture (Figure 1). It is preferred or recommended that therapy take place in a setting of physical and emotional safety and that barriers to effective therapy should be addressed (Van der Veer, 1992) (Figure 1).

It is also imperative that clinicians consider the various needs of clients and consider the theoretical conceptualisation of the needs in order to best formulate their interventions. It may be particularly helpful to consider Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in order to conceptualise which issues can be dealt with in therapy. The balance between ensuring psychological needs while understanding the survival needs of our clients is well illustrated in the quote below:

“The many urgent needs of torture survivors in exile confront mental health providers with direct confirmation of Maslow’s hierarchy. Psychological concerns must often take a backseat to more primary survival needs such as food, clothing, housing, physical safety, income and location of missing family members (The Centre for Victims of Torture, 2005’').

Maslow’s (1943) theory of human motivation, stipulates that the most basic need is the need to survive and the essentials that make survival possible are food, water and shelter. When these survival needs are not met, it compromises the need for safety and security to be met, which increases fear and anxiety. Ultimately, the impact of survival needs not being met impacts on one’s ability to engage and make meaningful social connections with others. Especially when the other is unfamiliar to you or maybe prejudice against you.

The Importance of the Therapeutic Relationship

As torture is perpetrated by people and affects the individual’s perception of the self and the world, the therapeutic relationship is one of the key elements that can provide an emotionally corrective experience for clients (Figure 1). This is highlighted in the quotation below:

“…Good trauma therapists come from every discipline, work in all settings, use a variety of approaches and techniques, and have a wide range of credentials and experience….the dual formulation of validation and empowerment seems to be fundamental to post traumatic therapy…the four most important things a therapist has to offer a survivor are as follows: respect, information, connection and hope’ (The Centre for Victims of Torture, 2005”).

A positive working alliance and therapeutic relationship has been acknowledged as an important contributor to the outcome of counselling (Kanninen, Salo & Punamaki, 2000). This notion is true of the general therapeutic encounter but it is of increasing importance when it comes to therapeutic intervention with victims of torture and trauma. The establishment and maintenance of this working alliance is dependent on interpersonal characteristics of the client such as attachment pattern and the ability to form social relationships (Kanninen, Salo & Punamaki, 2000).

Another element that speaks to building the therapeutic relationship is acknowledgement of what the client sees as a priority and responding to that priority. Respecting their ability to decide if they want to work on their trauma or contextual stressors. Demonstrating an understanding of the context and the challenges within that context helps clients feel understood, less alienated and most importantly these contextual issues that impact on their mental health is represented/ reflected in their treatment plan (The Centre for Victims of Torture, 2005).

Empowerment

Empowerment is seen as a fundamental principle to the mental wellbeing of our clients; especially clients who have been tortured, where disempowerment is a psychological impact of torture (Curling, 2005).

“For torture survivors, who may attribute enormous power to authorities, it is important to clarify the provider role, i.e., limits of power and what the provider offers. It is critical to explain who the provider is and how they can help in terms directly linked to the survivors situation and/or needs” (The Centre for Victims of Torture, 2005).

The Centre for Victims of Torture (2005) state that providing clients with information about services that we provide, limitations to what we provide and can offer in relation to their contextual needs and circumstances and allowing clients to make an informed decision about their healing pathway is seen as vital to the process of re-empowering clients and re-establishing their connection to their internal locus of control (LOC). Lack of information could lead to a sense of loss of personal power. Giving them back that power through providing client tailored information, explanation and choice is important (The Centre for Victims of Torture, 2005). The Centre for Victims of Torture (2005) highlights that healing has many paths and is subjective. It may mean symptom reduction, emotional processing of the trauma, service accessibility, psychological report on the psychological effects of the torture for the purposes of political asylum application, connectedness to others, or spiritual health.

Methodology

The article is a descriptive study, drawing on baseline data as part of a more comprehensive monitoring and evaluation process at the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, as well as through clinical reflections on therapy with a torture survivor in order to explore the complexity of providing psychosocial services to survivors of torture in contexts of continuous traumatic stress and daily stressors.

The data included in this article comprise of demographic information based on the screening and baseline information. Additionally, measures of psychiatric conditions and functioning include Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Self-Perception of Functioning, as measured in the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ); anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; three questions regarding locus of control, five questions adjusted from the International Classification of Functioning and Disability (ICF) including how the survivor fees that s/he is able to cope with family connections, external stressors, psychological difficulties, situations that made him/her angry and pain. The measures also include six questions based on the DeJong Versveld Connection to Others Scale, and lastly focuses on areas of pain. Through this, it is felt that a reasonable picture of the client’s psychological wellbeing may be measured over time.

Descriptive statistics are used to analyse the data in order to give a picture of the client sample at the CSVR.

Sample

A total number of 321 survivors accessing psychological assistance at the CSVR are included in the sample. Table 1 indicates the demographic information for the sample. The clients were closely divided along gender lines with 156 women (49%) and 165 men (51%). The average age is 34.34, with a minimum of 18 and maximum of 80 (SD = 8.79). Clients have an average of 2.3 children, with a maximum of 12 (SD = 2.26). Almost half of clients (49%) came from the Horn of Africa, while just over one third (35%) came from the Great Lakes region.

| Frequency | Percent | ||

| Gender (n=321) | Male | 165 | 51 |

| Female | 156 | 49 | |

| Nationality (n=321) | Ugandan | 7 | 2 |

| Rwandan | 9 | 3 | |

| Zimbabwean | 12 | 4 | |

| Eritrean | 14 | 4 | |

| Burundi | 25 | 8 | |

| Ethiopian | 67 | 21 | |

| Somali | 77 | 24 | |

| Congolese (DRC) | 97 | 30 | |

| Others* | 13 | 4 | |

| Marital status (n=313) | Currently married | 142 | 45 |

| Separated /Divorced | 31 | 10 | |

| Never married | 109 | 35 | |

| Widowed | 31 | 10 | |

| Currently living with (n=276) | Living alone | 33 | 12 |

| Living in a shelter | 16 | 6 | |

| Living with family/children | 102 | 37 | |

| Living with friends | 54 | 20 | |

| Living with spouse/partner | 36 | 13 | |

| Living with strangers | 35 | 13 | |

| Feel safe (n=280) | No | 216 | 77 |

| Yes | 64 | 23 | |

| Legal status in SA (n=314) | Asylum seeker | 130 | 41 |

| Citizen | 21 | 7 | |

| Temporary/Permanent resident | 3 | 1 | |

| Refugee | 142 | 45 | |

| Undocumented | 18 | 6 | |

| Pre-trauma employment (n=320) | Minor | 17 | 5 |

| Student | 37 | 12 | |

| Unskilled labour | 110 | 34 | |

| Semi-skilled labour | 42 | 13 | |

| Skilled labour | 41 | 13 | |

| Highly skilled/professional | 29 | 9 | |

| Unemployed | 44 | 14 | |

| Current employment (n=312) | Minor | 1 | 0 |

| Student | 5 | 2 | |

| Unskilled labour | 49 | 16 | |

| Semi-skilled labour | 13 | 4 | |

| Skilled labour | 10 | 3 | |

| Highly skilled/professional | 7 | 2 | |

| Unemployed | 227 | 73 | |

| Education (n=277) | No schooling | 28 | 10 |

| Some primary | 28 | 10 | |

| Completed primary | 23 | 8 | |

| Some secondary | 62 | 22 | |

| Completed secondary | 55 | 20 | |

| Tertiary | 68 | 25 | |

| Post-graduate | 13 | 5 | |

| Time since trauma (n=290) | Less than 2 weeks | 3 | 1 |

| 3 weeks - 1 month | 17 | 6 | |

| 2-6 months | 41 | 14 | |

| 7 months - 1 year | 45 | 16 | |

| 2-5 years | 86 | 30 | |

| 6-10 years | 64 | 22 | |

| 10+ years | 34 | 12 |

Table 1. Demographic information of sample

Almost half of the clients (45%) were married at the time of screening, while 35% had never been married. 41% of clients were living with strangers, in a shelter or alone. Additionally 77% of clients indicated feeling unsafe in their current living circumstances. 86% of clients were either refugees or asylum seekers, while 6% were undocumented (Table 2).

| Number | Percent of total traumas | Percent of number of clients who experienced trauma | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Torture/CIDT | 243 | 18 | 76 |

| Witness to trauma | 186 | 14 | 58 |

| Assault | 181 | 14 | 56 |

| Xenophobia | 111 | 8 | 35 |

| Bereavement/traumatic bereavement | 107 | 8 | 33 |

| War | 103 | 8 | 32 |

| Armed robbery | 102 | 8 | 32 |

| Rape/attempted rape/sodomy/sexual assault | 94 | 7 | 29 |

| Hostage/kidnapping/abduction | 59 | 4 | 18 |

| Mugging | 47 | 4 | 15 |

| Relationship/domestic violence | 29 | 2 | 9 |

| Hijacking | 25 | 2 | 8 |

| Car /motor vehicle accident | 17 | 1 | 5 |

| Other* | 35 | 2 | 11 |

| Number of types of traumas | 1339 | 100% |

Table 2. Traumas experienced by clients

50% of clients had a secondary education or higher. Prior to the trauma experience, 35% of clients were employed in semi-skilled, skilled or highly skilled/ professional employment, and 14% were unemployed. In contrast, after the traumatic event, 8% were employed in semi-skilled, skilled or highly skilled employment and 73% were unemployed (Table 2).

The majority of clients (52%) had experienced their trauma between two and ten years since coming to the CSVR trauma clinic, while 12% had experienced the trauma more than ten years previously (Table 2).

Almost two thirds (65%) of clients experienced pain at screening, with an average of 1.78 different areas of pain per client (SD = 1.98). Of those, an average of 0.60 was due to the torture / trauma experience. The maximum number of areas of pain was nine. The most reported areas of pain were the head and neck (121 clients), the back (86 clients), the lower extremity (76 clients) and the abdomen (71 clients) (Table 2).

Ethics

Ethical considerations were followed in this study in multiple forms. Firstly, all research go through an internal ethics process to ensure that no harm is met on clients. Secondly, all research ensures that there is anonymity and confidentiality for clients, whereby all clients are given a client code at screening, and all research uses client codes, rather than names or other identifying information. No identifying information of clients is used in research and M&E procedures, and if there is specific identifying information used,

Clients are given a consent form at baseline and are asked for consent both verbally and in writing, with the aspects of the consent form explained to clients prior to signing. Specific consent for the case study used in this research was ensured with the client.

All data is kept in a secure centralised monitoring and evaluation database. Hard copies of all open cases are kept in secure filing cabinets in clinicians locked offices, and hard copies of closed cases are kept in a locked storage room on the premises.

Results

Psychiatric Consideration

The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) provides three scores: A total trauma score, a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) score and a total trauma score. The Harvard Programme in Refugee Truama, which developed the HTQ suggests a conservative cut-off of 2.5 for clinical levels of PTSD, while no specific cut-off is suggested for self-perception of functioning and total trauma.

The average PTSD score for the sample is 2.76 (SD = 0.63) with 222 (69%) being checklist positive for PTSD. Clients indicated an average self-perception of functioning score of 2.60 (SD = 0.63) and a total trauma score of 2.67 (SD = 0.59).

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) provides a score for anxiety and depression, with a score of between 0 and 7 indicating normal levels of anxiety and depression, 8 to 10 indicating borderline levels of anxiety and depression, and 11 and above indicating clinical levels of anxiety and depression. There is a maximum score of 21 for both anxiety and depression using the HADS.

For our sample, clients indicated an average of 12.13 for anxiety (SD = 5.43) and an average of 11.48 for depression (SD = 5.25). The results for anxiety are represented in Table 3.

| Normal | Borderline | Clinical | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety (%) | 20 | 17 | 63 | 100 |

| Depression (%) | 21 | 18 | 61 | 100 |

Table 3. Results for anxiety and depression

Functioning and Social Indicators

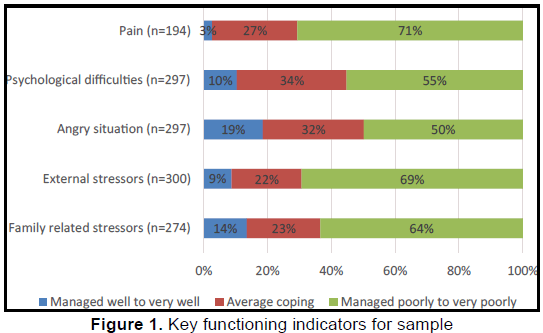

Questions were adapted from the International Classification of Functioning and Disability. The focus of these questions was the client’s ability to cope with their family connections, external stressors, situations of anger, their psychological difficulties and their pain.

Three questions regarding locus of control (LoC) are asked. The questions ask whether the client feels that what happens in their lives are mostly caused by powerful people, whether they feel that it is wise to plan ahead since things may be out of their control, and whether they work hard for things they want. While these have not been found to be reliable or valid, they are a useful source of information regarding client’s feelings of their own locus of control.

Largely clients feel an overwhelming lack of locus of control, however, the majority of clients (81%) indicate that they work hard for things they want (Table 4).

| Agree (%) | Disagree (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life determined by powerful people (n=307) | 76 | 24 | 100 |

| Plan too far ahead (n=295) | 69 | 31 | 100 |

| Work for things I want (n=305) | 81 | 19 | 100 |

Table 4. Locus of control indicators for sample

Six questions regarding connection to others are asked based on the DeJong Versveld Connection to Others Scale. While this scale has not been tested for reliability and validity in our context, however it was felt that this scale would be useful to understand the social, emotional and total isolation of clients.

Clients indicated feeling both emotionally and socially lonely. Out of a maximum of 3, they scored an average of 2.56 (SD = 0.72) for emotional loneliness, and 2.6 for social loneliness (SD = 0.77). Out of a maximum of 6, clients scored an average of 5.16 in terms of their total loneliness score (SD = 1.18).

Case Study

Based on information taken from refugees and asylum seekers seen at the CSVR trauma clinic, many have left their countries of origin as a result of war, political oppression and human rights abuses which are rooted in the continent’s colonial history, independence wars, the presence of dictatorships and both ethnic and civil conflicts (Higson-Smith, Mulder, & Masitha, 2006; Bandeira, Higson-Smith, Bantjies, & Polatin, 2010). As a result of the unrest occurring in their countries of origin and the atrocities associated with war times, several of these individuals have experienced various forms of torture and trauma and fled to South Africa to seek refuge and a better life. South Africa in the African continent, being perceived as the ‘Europe of Africa’, where a better life can be found. However, for many the reality is different and many refugees and asylum seekers face a number of contextual stressors which have a profound impact on their mental health wellbeing. Which furthermore, presents a complex mental health presentation.

The following case of study of E* reflects the experiences of clients seen at the CSVR trauma clinic:

Case Study: E*

E* is a political activist. She comes from a family of political activists. She reports times in her childhood, when her father was arrested because of his political activity. As he was the only breadwinner in the family this meant that at times they would go hungry. During her adolescent years, she had to live with a family friend, as her family could not take care of her. She moved around a lot, from family member to family member, because of this. Once E* completed her education, she began working and was witness to many things happening in her country which made her question the political system of her country. She then realised her father’s position on these matters and she too became a member of the political opposition party.

E* was arrested for her membership and involvement in the political activities of the opposition party shortly after joining the party. She was imprisoned with no legal procedures or formal charges for a period of 6 months. During this time, E* experienced torture by prison authorities, which included physical and mental torture, sexual abuse and other forms of cruel inhuman degrading treatment. She managed to escape with the assistance of a family friend. She went into hiding, but after a month, decided to leave the country, as she was not safe. The authorities continued to search for her, threatening her family members and arrested her father and brother on numerous occasions. E* does not know if they are still in prison or dead.

E* decided to travel to South Africa, as she had information that many refugees have fled to South Africa, as a place for refuge. E* along with a group of people travelled via bus and sometimes walked long distances in their travels. In total, it took E* two months to reach South Africa. E* states that the journey getting here was very difficult.

On arrival in South Africa, E* did not know anyone and had no money, as she had used it all in her travel to South Africa. She was able to connect with other people of her nationality whom shared the same political background and garnered support from them. They provided her with transport and directed her to a Refugee Receptions Office (RRO). At the time E* could not speak English, she was not provided with an interpreter to assist her to fill out forms. She had to improvise and asked for some money to get help from a person also in the queue, who was not a professional interpreter but spoke more English then E*. E* was given an asylum seeker permit, which had to be extended on several occasions. E* has been in South Africa for 12 years and is still identified as an asylum seeker.

Amongst the group of people she travelled with, she met a man, whom she befriended and he stated that he knew South Africa and would assist her in navigating her way when they got to South Africa. The two formed a relationship, which for E* was based on getting her basic needs met, as the man had financial resources and was able to provide E* with shelter and food. The two had established a restaurant business in a remote location in South Africa. E* was unaware of where the finances came from to provide the start-up for the business, she was just happy that she was able to have a life in South Africa, following her experience in her home country. The relationship, although providing financial benefits, was not stable, as E*s partner was involved in criminal activities, which E* later discovered and this led to complications in their relationship.

Two years from E*s arrival in South Africa and setting up home, E* was a victim of sexual (rape) and domestic violence, which was perpetrated by her then partner. Her first child is a result of this horrific rape experience. She reported the case to the police and left the relationship.

She moved from place to place in South Africa, seeking employment to support herself and her child. Getting work was hard because of her asylum seeker permit and as she had a child, who would take care of her child whilst she was at work? She was able, with help from friends she made along the way, to start a small business. However, that success was short lived, as the perpetrator found her again. E* was raped again by this man, in front of her young child.

That same year, she was scheduled for a refugee appeal hearing. She had an interview with the officer, who made it clear that in order for him to give her refugee status, E* would have to give him money. E* told him that she does not have money. He then stated that if she slept with him, he would give her refugee status tomorrow. E* refused. Following this, E*s application for refugee status was rejected and has been rejected on all other attempts. E* is still identified as an asylum seeker in South Africa.

By the time E* came to the CSVR Trauma clinic for counseling, she and her son were residing at a shelter for abused women. She had been placed there by police authorities following another rape experience by her ex- partner. At the time E* was ill and unemployed. She stated that she had tried to access medical assistance from the local hospital but was told at the hospital that asylum permit holders do not get treatment at the hospital unless they pay the full price. E* was very concerned, as well, about her current situation, as she could only stay at the shelter for six months before having to find alternative accommodation. Given the lack of improvement with her safety and financial situation, she was highly concerned.

E* presented with severe symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) with strong features of depression-related symptoms. Some of the symptoms that she presented with included: sleeping difficulties; hyper-arousal; poor concentration; intrusive thoughts and memories; and feelings of sadness and helplessness. These symptoms were noted as negatively affecting E*s functioning. She lived in fear, that she will be attacked again by the perpetrator, with this fear being paralyzing to the client, as she was fearful about going out in public or working. E* wanted counseling to help her understand and manage her trauma reactions and cope with her multiple rape experiences that continued to impact on how she interacted with others, especially men.

When E* began her counselling process with the therapist it was not easy to build rapport with her. She initially insisted her interpreter be present, even though she understood English. The therapist worked with this and respected her choice, understanding it as her needing the interpreter in the room for safety. The interpreter was the known in the relationship while the therapist was the unknown. One day, her interpreter was running late, the therapist started the session with E*s permission and they were able to communicate well. It was the first time the therapist felt connected to E* in the therapy space and thereafter E* continued without an interpreter. She felt safe with the therapist now.

In other spaces, moving from shelter to shelter, the same levels of distrust were initially shown to new people. The therapist worked with her to establish relationships or ‘acquaintances’ as she preferred to call it, as ‘relationship’ indicated that E* would have to share personal parts of herself with another, which she was not willing to do, as she did not trust them. The purpose of establishing ‘acquaintances’ was that it would assist in her addressing her safety concerns. For example, being placed in the shelter for abused women, she divulged that her perpetrator was still looking for her to other residents. One day when he came to the shelter, parked outside, he asked for her and a women who knew her told him she did not know the women he asked of, and informed the client to be careful. With time the client was able to build relationships with others, decrease her isolation but the distrust remained. Albeit it stopped limiting her functioning or ability to get her needs met.

As the therapy process continued, E* brought more and more of her experiences of flashbacks and nightmares into the space. We began processing these experiences and had entered the realm of gradual exposure therapy. At that time, E* had resources in place to support her, as she was very content at the shelter, she felt safe there as there were police stationed on the premises. E* had made friends with other women at the shelter and starting reconnecting with members of her own nationality and integrating into that sub-community. She had also started going to church again and established a network of support in that forum. During this period, E* was able to reflect on her feelings of intense anger, betrayal and regret.

Reflecting on her life before she was imprisoned and tortured. E* describes herself as a tomboy. She states that she was the only girl amongst 3 brothers and the apple of her father’s eye. She stated that she was stubborn and hard headed, but knew her father admired her because of those qualities. She was strong. She reported on instances where men would try to take advantage of her and she would physically defend herself. She was able to match them physically, despite being petite in size.

It has been 12 years since she was imprisoned for her political activities, tortured and raped during her imprisonment and then raped and abused again in South Africa. Sitting in the therapy room E* seems a different person from the one she describes. She struggles to deal with her own feelings of disempowerment that her experiences have left her with. Exploring this in counselling would often lead to E* dissociating from the space. And when she did engage with it, the feelings of disempowerment were so overwhelming that it would take weeks for E* to come out of a depressive mood state.

In the counselling process, E* also questioned her purpose/role to the political cause of her countrymen and her own purpose/role to her family. She reflected on the possibility that she could have been financially established by now and be able to provide for her aging parents. She questioned why she was being punished for standing up for what she believes in and what was right.

The therapeutic space worked on providing E* with containment and symptom management skills. A month and a half into therapy, E* missed a session for the first time. She came to the office a week later. E* stated that she had been very ill, she had ulcers, was on medication for high blood pressure and had not been coping. Exploring this in the session. E* stated that her perpetrator had come back; he was living in an area close to her. She saw him at the church. He did not see her, but he had been asking about her. She was afraid that he would find her again, as he had many times before. The people from the church felt that she should meet with him, as he is the father of her son. She was very upset by this. She felt they betrayed her and do not understand what she had been through.

She was also being evicted from the shelter, as her staying period had lapsed. At this point and to date, the therapeutic work with E* has become more supportive in nature, taking on a predominantly psychosocial approach, as she navigates her contextual stressors. E*s latest diagnosis by a psychiatrist was Major Depressive Disorder. Compounded with her experience of continuous daily stressors, it has become hard for E* and the therapist to manage her diagnosis and keep her stable, as E*s context needs to change to improve the prognosis, but the context change is highly unlikely.

Discussion

Drawing from the above literature and reflections of clients seen at the CSVR Trauma Clinic, it is acknowledged that mental wellbeing can be placed at risk by various biological, psychological and social factors. Taking into account the case of E* and other similar cases seen at the CSVR Trauma Clinic, a history of trauma in the family and community is noteworthy. Clinical observation and empirical evidence has shown that the effects of trauma and torture are not limited to the victims, but also have a profound effect on their significant others (Ancharoff, Munroe & Fisher, 1998 as cited in Dekel & Goldblatt, 2008). Furthermore, as we review the countries of origin that our clients come from and the long history of violence and unrest, it is evident multiple generations have been victims of violence.

The aftermath of the trauma or torture presents further challenges for the individual, as they face stressful social and material conditions, which is often characterised by poverty, malnutrition and displacement into overcrowded and impoverished refugee camps (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010). The individual experiences the loss of social support as a result of lost family members due to death or separation. Those who are not placed in refugee camps, face a dangerous and risky journey, as they migrate-often illegally-across various parts of Africa to make their way to South Africa. Hence, the individual undergoes a number of traumas caused by war or armed conflict in their home country that surpasses the experience of a single traumatic event, as a number of traumas have taken place before they reach South Africa, as noted in the case of E*.

The mental health status of these individuals on arrival in South Africa can be seen to reflect a state of confusion and disorientation, impacting on the individual’s ability to connect with others, specifically in the case of refugees and asylum seekers, impacting on their ability to present their refugee claim in a cohesive manner (Kenny, 2016). This results in many individuals being denied refugee status, and the accompanying rights, and they then have to contend with an asylum seeker permit for a lengthy period of time which further places them in a state of vulnerability as their documentation limits their ability to fully integrate into South African society and holds them constantly on the periphery of society. Furthermore, Onuoha (2006) explains that discrimination and lack of awareness of what a refugee and asylum seeker permit holder is entitled to makes access to medical, legal and social services harder. This is illustrated in E*s difficulty in finding employment due to the limiting nature of her documentation, as well as her struggle in accessing public health care services.

The psychological salience of daily contextual stressors is emphasised by Kubaik (2005) as contributing to the erosion of clients coping resources. This was especially noted in the case of E*, who presented with personality traits of hardiness in the beginning of the counselling process, which served as a buffer to the contextual stressors she had en-counted. However, with the accumulation of contextual stressors and pervasive nature of these stressors, as well as the overloading of the allostatic load, E*s coping resources were being eroded. E, as well as other clients seen at the CSVR Trauma Clinic often suffers from physical ailments such as high blood pressure, ulcers and chronic headaches. This highlights the existence of a relationship between chronic stress and its impact on the immune system that manifests in illness (Salleh, 2008).

Furthermore, Miller and Rasmussen (2010) argue that daily stressors are stressful when they are out of our control. This is exactly the case for many refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa where the daily contextual stressors are very much out of their control, fuelling the feeling of disempowerment and confirming the perception that power lies in the outside of the individual. As such, an external locus of control is evident, bringing about a decrease sense of agency to bring about change. This phenomenon was evident in the case of E* as she perceived UNHCR as being an authority figure with endless the power and herself as having no power to create change. Assessments done with torture survivors have noted a high external LOC, as clients feel lost and rely on authority figures to provide some form of stability.

Taking into account the impact of daily contextual stressors on the mental wellbeing of refugees and asylum seekers seen at the CSVR Trauma Clinic and the residual impact of war trauma and torture on their mental wellbeing, the CSVR Trauma Clinic has taken a more psychosocial approach in working therapeutically with refugees and asylum seekers to build resilience and facilitate healing by targeting the aforementioned issues of disempowerment, stress and coping, and symptom management. It is acknowledged that victims of war trauma, who have fled their country, have a range of needs. It is not uncommon for more urgent or distressing problems to be fore-grounded in counselling, such as the provision of basic needs or work with daily stressors (Higson-Smith, Mulder, & Masitha, 2006). Thus, the therapeutic work, aimed at the torture or trauma experience is often only tackled in later stages of counselling or not all. At the CSVR Trauma Clinic, we find ourselves, in most cases, stuck in phase one and at the same time juggling with what Herman (1997) identified as the two other phases that are important to any successful intervention with survivors of torture: treatment involving psychotherapy and medication; and re-integration.

Trauma reactions that are awoken by contextual experiences need to be dealt with, however there is not a space to engage with this due to the client’s lack of physical or emotional safety and stability, therefore more pressing needs need to be addressed, such as shelter, food etc. Containing the client and mobilising resources becomes precedent for the client over emotionally processing the flashback that was triggered. With contextual challenges, especially threat of further violence, it is acknowledged that for some clients only limited gains are possible. These limited gains can still be viewed as a form of progress which is beneficial in its own manner (Turner, 2000).

Providing a sense of safety, primarily emotional safety, within the counselling space is of paramount importance as clients emotional and physical safety status fluctuates. The glue that holds this therapeutic encounter with the client has been identified as the therapeutic relationship. Providing a safe space for our clients is a priority at the CSVR Trauma clinic. We cannot guarantee physical safety outside of our offices, but within them clients have reported that they feel safe, they feel heard and acknowledged. Fostering this has been the therapeutic relationship and the building of that relationship from the moment the client is contacted for an appointment. Furthermore, due to the several human rights violations and the repeated victimisation experiences by refugees in South Africa, it stands to reason that they develop issues around trusting people. This is where the therapeutic relationship becomes important. Therapists must work tirelessly in establishing a strong therapeutic relationship in which the client feels safe enough to engage genuinely.

Moreover, the contextual stressors are experienced as overpowering by the client and therapist; however it is necessary in conceptualising the client’s mental health presentation. In addition, it is beneficial to engage with contextual needs through a psychosocial case management lens in attempts to get basic needs such as shelter and food for refugees and asylum seekers. The ways in which this can be done include building referral connections or working partnerships with other organisations who work with refugees and asylum seekers needs, specifically, and as well as other organisations. Currently, there are a small group of organisations in South Africa that address some of the major contextual daily stressors highlighted in this paper.

It is also beneficial to engage in holistic case management initiatives, whereby, mental health, social and legal needs representatives for clients discuss cases and mobilise resources to assist. However, the limited resources of social assistance organisations also have an impact on the therapeutic work done.

It has also been noted that refugees and asylum seekers are a specialised type of population and they are often misunderstood and mistreated by service providers that are not accustomed to the sensitive nature of this population group. Service providers often mirror the larger society’s attitude of intolerance towards foreigners. This may further impact therapeutic healing and exacerbate the client’s feelings of isolation. This necessitates multi-level intervention from community-level awareness rising to policy changes at local, regional, national and international level. Thus, clinicians working in this field find themselves expanding on their traditional roles to be inclusive of engaging with more case management initiatives, advocacy and accompaniment (The Centre for Victims of Torture, 2005). The multiple roles may in some ways be contrary to traditional psychological practice. Clinicians may fear that clients would become dependent on them to be their advocates in getting their basic needs met, dependent on the therapeutic space as a surrogate family supplement, and the perception of external LOC holding all the power and them not having any sense of agency would continue. Thus, it is important to acknowledge that our engagement at a psychosocial level has implications for the therapeutic work, as well as the client’s ability to access services independently.

In attempts to address the contextual challenges faced by clients and challenges it creates in the therapeutic intervention, the CSVR trauma clinic utilises cognitive behavioural theory with an over-arching empowerment approach (Bandeira, 2013a) This approach speaks to the contextual challenges that refugees and asylum seekers face in South Africa and ways of addressing these challenges in a therapeutic manner, with the aim of increasing internal LOC, building self-esteem and sense of agency; developing problem solving and coping skills; and dealing with difficulties from service providers and nationals; and looking at effective ways of getting needs met; and symptom management.

This approach aligns well with the goal of enhancing resilience in clients, as resilience is enhanced by an internal LOC, comprehensive social support, optimism and the use of problem-solving strategies (Ayalon, 2005). Other factors that enhance resilience is meaning making of traumatic experiences, stability and the ability to build on their own strengths (Ayalon, 2005). Thus, through the therapeutic work with individuals the focus has been building resilience to daily contextual stressors and helping clients find ways of sustaining that resilience. As noted in the case of E, her levels of resilience fluctuated dependent on her experience of contextual stressors and she found the therapeutic space and therapeutic relationship as her container to manage these.

The above reflects key issues mental health practitioners working with torture survivors that face daily contextual stressors need to consider in their therapeutic interaction, as the mental health presentation of these individuals are complex and often fluctuate between dealing with past trauma impacts and exposure to daily contextual stressors (Figure 1).

Conclusion

The experience in therapy with refugees and asylum seekers in this context often takes on a blend of trauma focused and psychosocial interventions. And often, therapist battle with staying on the surface and going in depth into the trauma memories, as the context the client often is in does not allow or support deeper exploration. Therapist are mindful of the allostatic load being flooded with daily stressors and there is concern around the clients ability to hold themselves and their spaces if an in depth exploration of the trauma would take place. In addition, the context the client and therapist find themselves in is unreliable and the therapeutic focus shifts to accommodate the client’s current needs. The client’s mental health and resilience levels are challenged daily and the therapeutic space often serves as a container to symptom manages development and sustainability of levels of resilience.

References

- American Psychiatric Association.(2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5thedn.).Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing

- Ayalon, L. (2005). Challenges associated with the study of resilience to trauma in Holocaust survivors. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 10, 347-358

- Baird, E., Williams, A. C De C., Hearn, L., Amris, K. (2016). Interventions for treating persistent pain in survivors of torture (Protocol).UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd

- Bandeira, M. (2013). Developing an African torture rehabilitation model: A contextually- informed, evidence-based psychosocial model for the rehabilitation of victims of torture. Part 1: Setting the foundation of an African Torture Rehabilitation through research. Johannesburg:Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation

- Bandeira, M., Garcia, M., Kekana, B., Naicker, P., Uwizeye, G., Smith, E., et al. (2013). Developing an African torture model: A contextually-informed, evidence based psychosocial model for the rehabilitation of victims of torture. Part 2: Detailing an African Torture Rehabilitation Model through engagement with the clinical team. Johannesburg: Unpublished report by the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation

- Bandeira, M., Higson-Smith, C., Bantjies, M., &Polatin, P. (2010). The land of milk and honey: a picture of refugee torture survivors presenting for treatment in a South African trauma centre. South Africa: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation

- Birman, D., Ho, J., Pulley, E., Batia, K., Everson, M. L., Ellis, H., et al. (2005). Mental health intervention for refugee children in resettlement: white paper II. National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59, (1), 20-28

- Bonanno, G. A., Field, N. P., Kovacevic, A., &Kaltman, S. (2002). Self-enhancement as a buffer against extreme adversity: Civil war in Bosnia and traumatic loss in the United States. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 184-196

- Brune, M., Haasen, C., Krausz, M., Yagdiran, O., Bustos, E., Eisenman, D., et al. (2002). Belief systems as coping factors for traumatised refugees: a pilot study. European Psychiatry, 17, 451-458

- Christopher, M. (2004). A broader view of trauma: a biopsychosocial –evolutionary view of the role of the traumatic stress response in the emergence of pathology and growth. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 75-98

- Curling, P. (2005).The effectiveness of empowerment workshops with torture survivors.Torture Journal, 15, 9-15

- Dekel, R., &Goldblatt, H. (2008). Is there intergenerational trauma? The case of combat veteran’s children.American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78 (3), 281-289

- Ebert, A., &Dyck, M. (2004). The experience of mental death: The core feature of complex PTSD. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 617-635

- Florain, V., Mikulincer, M., &Taubman, O. (1995). Does hardiness contribute to mental health during a stressful real-life situation? The roles of appraisal and coping.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 687-695

- Fredrickson, B. L., &Levenson, R. W. (1998). Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 12, 191-220

- Hensel-Dittman, D., Schauer, M., Ruf, M., Catani, C., Odenwald, M., Elbert, T., et al. (2011). Treatment of traumatised victims of war and torture: A randomised controlled comparison of narrative exposure therapy and stress inoculation training. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 80, 345-352

- Herman, J. (1997). Trauma and recovery.The aftermath of violence-from domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books

- Higson-Smith, C. (2013). Counselingtorture survivors in contexts of ongoing threat: Narratives from Sub-Saharan Africa. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 164-179

- Higson-Smith, C., & Bro, F. (2010).Tortured exiles on the streets: a research agenda and methodological challenge.Intervention, 14-28

- Higson-Smith, C., Mulder, B., &Masitha, S. (2006). Human dignity has no nationality: A situational analysis of the health needs of exiled torture survivors living in Johannesburg, South Africa. [unpublished research report]. Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation

- Jaranson, J. M., &Quiroga, J. (2011). Evaluating the services of torture rehabilitation programmes: History and recommendations. Torture?: Quarterly Journal on Rehabilitation of Torture Victims and Prevention of Torture, 21(2), 98–140

- Kanninen, K., Salo, J., &Punamaki, R. (2000).Attachment patterns and working alliances in trauma therapy for victims of political violence.Psychotherapy Research, 10, 435-449

- Kenny, M. A. (2016). The importance of psychosocial support in the refugee status determination process

- Kubaik, S. (2005).Trauma and cumulative adversity in women of a disadvantaged social location.American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75, 451-465

- Langa, M. (2013).Exploring experiences of torture and CIDT that occurred in South Africa amongst non-nationals living in Johannesburg. [unpublished research report]. Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation

- Mamud, S. (2005).Responding to continuing traumatic events.The International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work.2005, 54-56

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation.Psychological Review, 50 (4), 370-396

- McFarlane, A. C. (2010). The long-term costs of traumatic stress: intertwined physical and psychological consequences. World Psychiatry Journal, 9(1)

- McKnight, J. (2008). Through the fear: A study of xenophobia in South Africa’s refugee system. Journal of Identity and Migration, 2 (2), 18-42

- Miller, K.E. & Rasmussen, A. (2010). War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 7-16

- Onuoha, E. C. (2006). Human rights and refugee protection in South Africa (1994-2004). Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand

- Palmary, I. (2006). Refugees, safety and xenophobia in South African Cities: The role of local government. [unpublished research report]. Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation

- Patel, N. (2003). Speaking with the silent: addressing issues of disempowerment when working with refugee people. In R, Tribe (Eds), Working with interpreters in mental health. East Essex: Brunner-Routledge

- Procter, P., Ilson, R. F., &Ayto, J. (1978).Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. London: Harlow

- Rasmussen, A., Rosenfeld, B., Reeves, K., & Keller, A.S. (2007). The effects of torture-related injuries on long-term psychological distress in a Punjabi Sikh sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 6(4), 734-740

- Salleh, M. R. (2008). Life event, stress and illness. Malaysian Journal of Medical Science, 4, 9-18

- Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers. New York: Owl Books

- Schweitzer, R., Greenslade, J. &Kagee, A. (2007). Coping and resilience in refugees from the Sudan: A narrative account. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 41 (3), 282-288

- Sinclaire, M. (1999).“I know a place that is softer than this…”-Emerging migrant communities in South Africa.International Migration, 3 (2), 465-481

- Tebogo, S. (2005).Forced migrants and social exclusion in Johannesburg. In L, Loren (ed), Forced Migrants in the New Johannesburg. South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand

- The Centre for Victims of Torture. (2005). Healing the hurt: A guide for developing services for torture survivors. Minneapolis: The Centre for Victims of Torture

- Turner, S. (2000). Psychiatric help for survivors of torture.Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 6, 295-303

- Turner, S. &Gorst-Unsworth, C. (1990). Psychological sequelae: a descriptive model. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 475-480

- Ullman, R. & Brothers, D. (1988). The shattered self: A psychoanalytic study of trauma. London: Analytic Press

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). What is mental health?

- Van der Veer, G. (1992). The experience of refugees in counselling and therapy with refugees: Psychological problems of victims of war, torture and repression. Chichester: Wiley

- Weinberger, D. A. (1990).The construct validity of the repressive coping style. In J. L. Singer (ed.), Repression and dissociation: Implications for personality theory, psychopathology and health. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 13156

- [From(publication date):

December-2016 - Apr 08, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 12449

- PDF downloads : 707