Commentary Open Access

The Promise of Intersectional Stigma to Understand the Complexities of Adolescent Pregnancy and Motherhood

Brittany D Chambers* and Jennifer Toller Erausquin

Department of Public Health Education, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, School of Health and Human Sciences, Greensboro, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Brittany D Chambers

Department of Public Health Education

University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Greensboro, NC, School of Health and Human Sciences

437 Coleman Building, PO BOX 26169

Greensboro, NC 27402-6169, USA

Tel: 3363345287

Fax: 3362561158

E-mail: bdchambe@uncg.edu

Received Date: September 04, 2015 Accepted Date: October 02, 2015 Published Date: October 09, 2015

Citation: Chambers BD and Erausquin JT (2015) The Promise of Intersectional Stigma to Understand the Complexities of Adolescent Pregnancy and Motherhood. J Child Adolesc Behav 3:249. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000249

Copyright: © 2015 Chambers BD, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior

Abstract

For decades, adolescent pregnancy prevention strategies focused on proximal determinants. These strategies resulted in impressive declines in US adolescent pregnancy and birth rates, reaching historic lows in 2014. However, disparities in adolescent birth rates by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status persist. Further, not only are adolescents of color and those who live in underserved communities more likely to become pregnant, they are also more likely than their white and more affluent peers to experience negative health and social consequences of pregnancy and parenthood. More distal or “upstream” factors, such as social stigma, may cause these persistent disparities. This paper aims to build upon a nascent framework, intersectional stigma, and show how it may shape efforts to address the needs of adolescent mothers. Stigma is defined as a deeply discrediting attribute that marginalizes groups of people as “other.” Intersectional stigma posits that individuals may experience stigma resulting from the dynamic interaction of multiple marginalized social identities. Adolescent pregnancy and motherhood often cross multiple oppressed identities (e.g., minority race/ethnicity, single motherhood, low socioeconomic status), resulting in intersectional stigma. This stigma is experienced at school, in healthcare and social services, through media, and in public. As a result, adolescent mothers describe experiencing shame, guilt, and unhealthy coping strategies including avoiding the locations and institutions involved in their experience of stigma. Doing so can lead to repeat births and delinquent behaviors. The intersectional stigma framework provides a guide to the development of interventions to reduce stigma and improve outcomes for pregnant and parenting adolescents.

Keywords

Stigma; Intersectionality; Adolescent pregnancy; Adolescent motherhood; Teen discrimination

Introduction

Adolescent birth rates have substantially declined in the United States (US), particularly in the past two decades, and are now at historic lows [1]. Nevertheless, a disproportionate burden of adolescent births persist among youth of color and who are from disadvantaged communities [1].

However, disparities in adolescent birth rates by race/ethnicity and community socioeconomic status persist. Further, not only are adolescents of color and those who live in underserved communities more likely to become pregnant during their teen years, but they are also are more likely than their white and more affluent peers to experience negative health and social consequences of pregnancy and parenthood [2].

The transition to adolescent motherhood is associated with higher risk of many negative health outcomes, in comparison to women who delay pregnancy until adulthood. For example, adolescent mothers are more likely to drop out of high school, head single-parent households, and live in continuous poverty, in comparison to adolescents who delay pregnancy until adulthood [1]. This is particularly problematic since 10% of births in the US are to adolescent mothers, and 1 in 5 of births to adolescent mothers are repeat births [3]. Adolescent mothers who have repeat births during adolescence are at higher risks for experiencing these adverse effects [4].

Research suggests the transition to motherhood alone is not the cause of adverse effects for adolescent mothers; rather, adolescent pregnancy and motherhood perpetuate social injustices experienced by people of color and youth from disadvantaged communities [5]. The racial/ethnic, class, and gender-based disparities in health and social outcomes associated with the transition to motherhood for young mothers are the result of distal, or “upstream,” factors, such as social stigma.

Adolescent pregnancy and motherhood is a complex phenomenon intersecting multiple oppressed or marginalized identities (e.g., minority race/ethnicity, single motherhood, low socioeconomic status), which may result in an intersectional stigma. The aim of this paper is to apply and build upon a nascent framework, intersectional stigma, to guide the development of secondary prevention programs to address the needs of adolescent mothers as they transition to and navigate within motherhood.

Trends in adolescent birth rates

There has been a consistent decline in adolescent birth rates in the US for the past several decades [1]. For example, in 2013 only 26.4 per 1,000 adolescent females aged 15-19 gave birth, representing a 10% decline in adolescent birth rates from 2012 [1]. Similarly, there has been a decline in adolescent birth rates for all racial and ethnical groups; nevertheless, birth rates for African American and Latino females aged 15-19 are more than two times those of White adolescent females [1].

Although reasons for declines are not concrete, more adolescents appear to be delaying the initiation of sexual intercourse, and sexually active adolescents using more effective forms of birth control in comparison to previous years [1].

Stigma and intersectionality

Intersectional stigma draws from three principal constructs and theories: stigma, intersectionality, and critical race theory

Stigma

The concept of stigma is most commonly credited to Goffman [6], who defined the concept of stigma as an “attribute that is deeply discrediting,” and that marginalizes groups of people, such as adolescent mothers, “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one”. Stigma involves an interaction between a stereotype and attribute (e.g., adolescent mothers are promiscuous), resulting in a social identity, separating groups of people with undesirable characteristics from those with desirable ones [6].

As a result of this interaction, people with desirable characteristics construct a stigma-theory, or a social understanding to make sense of differences between groups of people. The stigma-theory classifies those with undesirable characteristics as dangerous to society. This can result in animosity towards groups of people with undesirable characteristics, and ultimately leading to consequences ranging from social exclusion to bodily harm [6].

Goffman et al. [6] describes three circumstances in which stigma occurs: against people who have physical abnormalities, who pose characteristics deviating from the social norm, and a “tribal stigma” of religion, race, and nation. Many definitions have developed since Goffman et al. [6] [see for example, [7-9], causing scholars in the field to have somewhat varying conceptualizations, definitions, and measurements of stigma

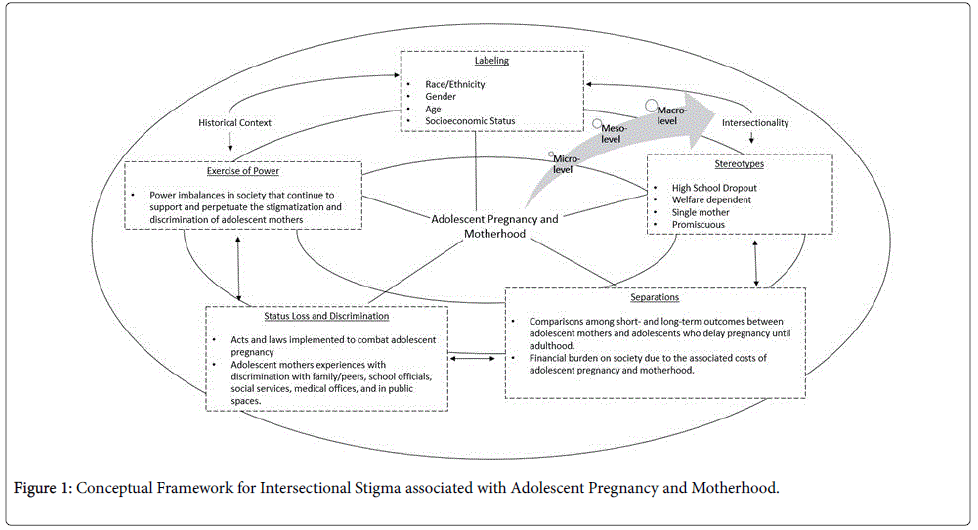

From a public health perspective, Link and Phelan [10] have conceptualized stigma as a dynamic social process governed by political power, social status, and wealth constructing “ideal” social identities, and leading to structural differences in society. In their view, there are five co-occurring stigma processes: labeling, stereotypes, separations, status loss and discrimination (individual and structural), and the exercise of power.

Therefore, stigma is a broach concept encompassing the process of social constructions of differences between groups of people based upon physical attributes, and the negative effects this process can have on groups of people on the individual and structural levels [10,11]. On the other hand, discrimination only accounts for the negative treatment of a group of people through direct interactions and institutional laws and practices to continuously disadvantage a group of people [10]. Many scholars have argued this process of stigma is a fundamental cause for health disparities seen in the US [11].

These evolving definitions of stigma indicate it is a complex phenomenon beyond the individual, and different forms of stigma may exist at the different levels of human social ecology [11,12]. There are multiple forms or manifestations of stigma: internalized stigma (i.e., the acceptance of negative attributes of one’s own social identities), enacted stigma (i.e., experienced discrimination from a person based upon one’s social identities), symbolic stigma (i.e., community norms towards discrimination of groups of people based upon their social identities) and structural stigma (i.e., establishment of discriminating laws and enforcement towards groups of people based upon their social identities) [12]. The different manifestations of stigma are important to consider when examining adolescent pregnancy and motherhood, since they suggest multiple ways in which stigma may shape attitudes, experiences, and behaviors.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality was introduced by Black feminist scholar Crenshaw [13] to capture the multidimensionality of systems of oppression being inflicted upon African American women. Crenshaw [13] argued African American women are centered in society based upon a dynamic intersection among their race, gender, and class.

This dynamic intersection is created and perpetuated by an interaction between micro-level categories (such as race, gender, and class) and macro-level structures (such as racism and sexism), recognizing historical systems of privilege and oppression in the American society. Crenshaw [13,14] has used an intersectional framework to explore structural discrimination experienced by African American women seeking justice through the judicial system and obtaining supportive services after experiencing a battery or rape.

Although there has been dialogue on the benefits of intersectionality in public health research, there is a dearth of basic research articles applying this theoretical framework to understand health issues [15]. Furthermore, Bowleg [15] calls for a broader conceptualization of intersectionality in public health to include a “matrix of domination,” recognizing all people who are oppressed in a privileged society, such as White women from disadvantaged communities and Black heterosexual men.

Intersectional stigma

Intersectional stigma is a nascent theoretical framework that draws from both intersectionality (i.e., dynamic intersection among social identities) and stigma (i.e., process of othering a group of people in society) [16]. Intersectional stigma can be used to understand the complexity of the manifestation (i.e., macro-level structures) and lived experiences (i.e., micro-level factors) of discrimination towards groups of people who have multiple oppressive social identities [16].

Intersectional stigma has been used primarily in HIV research to understand women’s experiences with being HIV-positive while also having other oppressive social identities [16-18]. For example, Berger [16] has used intersectional stigma to explore resilience and advocacy efforts among HIV-positive American women.

Applying an intersectional stigma framework to adolescent pregnancy and motherhood: An intersectional stigma framework may be an important tool to examine the experiences of adolescent mothers as they transition to and navigate within adolescent motherhood, and to make sense of the determinants of persistent health and social disparities experienced by adolescent mothers. Intersectional stigma has the potential to inform the development and implementation of more comprehensive, evidence-based secondary prevention programs for pregnant and parenting adolescents. The processes of intersectional stigma as experienced by and perpetuated on pregnant and parenting adolescent mothers will be discussed (Figure 1).

Labeling involves creating categories used to classify groups of people in society by their social identities, and can change overtime as societal norms shift [8]. Stereotypes are the association of negative attributes to the labeling of groups of people, marginalizing certain social identities as “other” in society [8]. Labeling of adolescent motherhood has changed dramatically over. Prior to the 1970s adolescent motherhood was not labeled as a health issue [3,19]. However, due to a rapid decline in marriages and adoptions among pregnant adolescents, views of adolescent pregnancy and parenting changed to a “problem” [3,19]. Simultaneously, the social construction of motherhood emerged in the 1960s as white, middle-classed, and married women, marginalizing groups of people such as women of color, low-income, adolescent and single mothers, creating a dichotomy between “good” and “bad” mothers [20]. Adolescent pregnancy and motherhood often intersects among these marginalized groups, thereby labeling adolescent mothers as “bad” mothers [21]. For example, the majority of adolescent births are to youth of color and those who reside in underserved communities, representing an intersecting of oppressive social identities. This idealization of adolescent pregnancy and motherhood has transpired to newspaper and public policy headlines over the years labeling adolescent mothers as deviant, promiscuous, and immature/irresponsible youth. This process of labeling can led to the stereotypes classifying adolescent mothers as “other” in society.

Separations are an effect of the relationship between labels and stereotypes, creating dichotomies between groups of people, the “us” verses “them” paradigm [8].

Separations between adolescent mothers and adolescents who delayed motherhood emerged with increases in access to birth control and single mothers [22]. In response, the National School-Age Mother and Child Health Act argued: “(1) pregnancy among adolescents is a serious and growing problem; (2) such pregnancies are the leading cause of school dropout, familial disruption and increasing dependency on welfare and other community resources” [23]. Although this act was not passed, it was the first discussion in the politic sphere labeling adolescent pregnancy as a problem. As a result, there was an increase in empirical and review articles agreeing with adolescent motherhood is associated with dropping out of high school, heading single parent households, relying on government assistance and living in continuous poverty [24-26]. However, in reflecting over the past 20 years on research and programs aimed at understanding the consequences of adolescent pregnancy and prevention efforts, Kirby [27] revealed early studies addressing the consequences of adolescent pregnancy reported inaccurate results. Current research indicates that in controlling for background characteristics, negative consequences associated with adolescent pregnancy and motherhood are substantially reduced or eliminated including educational attainment, welfare dependency and poverty [27]. Yet, these stereotypes continue to inform policy-related prevention strategies to address adolescent pregnancy and motherhood, creating and maintaining separations between adolescent mothers and adolescents who delay pregnancy until adulthood.

Status Loss and Discrimination are effects of stigma. A person’s status in society can decrease due to them possessing negative attributes [8]. There are two forms of discrimination, structural discrimination (i.e., institutional practices used to continuously disadvantage groups of people) and individual discrimination (i.e., direct interaction between two people where one person discriminating against another person) [8]. There is an interaction between structural and individual discrimination, where both must exist in society in order for stigma to be developed and perpetuated in society.

Forms of structural discrimination can be seen through the establishment of many acts and laws pertaining to people of color, adolescents, and mothers. Although the majority of these acts were implemented to address inequalities, these laws can negatively impact the lives of adolescent mothers, including socially constructing adolescent motherhood as a “problem” and limiting funding for services tailored towards adolescent mothers [28]. For example, historically people of color and pregnant women were segregated and/or isolated from US educational systems. People of color were allowed to attend “White only” public schools beginning in 1954 through Brown vs. the Board of Education and pregnant adolescents in 1978 through the Pregnancy Discrimination Act [28,29]. Despite these important policies, adolescent mothers reported experiencing enacted stigma in medical offices and clinics, social services, at school, and in public spaces [30-35]. In fact, there are still schools for adolescent mothers’ schools exclusively across the US. Enacted stigmas experienced by adolescent mothers can be due to their race/ethnicity, status as an adolescent mother, or the intersection of the two. Enacted stigmas in institutions and public spaces have been reported across studies with different samples of adolescent mothers, indicating there may be a form of structural discrimination occurring within these institutions.

Also, the Adolescent Health, Services, and Pregnancy Prevention Act of 1978 launched the national campaign to prevent teen and unplanned pregnancy (NCPTUP), suggesting adolescent pregnancy and motherhood has negative immediate and long-term impacts on adolescents’ lives [23]. According to NCPTUP [34], 372, 000 births occurred to women under the age of 20, spending $9.4 billion tax dollars. This has led to the development of evidence-based adolescent pregnancy prevention efforts nationwide. Although these prevention programs have contributed to the reduction of adolescent pregnancy in the US, few studies explore the harm in which such programs may impose on pregnant and parenting adolescents. For example, Kearney and Levine [36] found the MTV series 16 and Pregnant (now known as Teen Mom), a NCPTUP prevention strategy, resulted in a 5.7% decrease in adolescent pregnancy rates. However, a series of critical essays on 16 and Pregnant reveals the series actually creates and perpetuates stereotypes of adolescent motherhood through the overemphasis on the adverse effects of adolescent pregnancy and motherhood and the portrayal of adolescent mothers as “bad mothers” [35]. For example, 16 and Pregnant portrays the “good mom,” as an adolescent mother who prioritizes her motherly duties and overcomes the stereotypes of the “typical” (e.g., welfare dependency, high school dropout, etc.) adolescent mother [35]. In contrast, a “bad-mom” is characterized as an adolescent mother who neglects her child to participate in traditional adolescent behaviors such as parties, makeup, and hanging out with friends [35].

Exercise of power suggests stigma cannot exist with power imbalances in society making clear distinctions between groups of people according to social identities [8]. This includes discrimination against people who belong to certain social identities but do not necessarily portray negative attributes [8].

Conclusion

Intersectional stigma towards adolescent mothers can have negative consequences for their health and wellbeing. Wiemann, Rickert, Berenson and Volk [37] reported 39.1 % of adolescent mothers’ experienced enacted stigma as a pregnant teen. Predictors of stigma included being white, not married or engaged; and experiencing violence, criticism, and social isolation from family and peers, as well as aspirations to complete college [37]. As a result, adolescent mothers reported experiencing internalized stigma (i.e., shame and guilt), often leading to unhealthy coping strategies such as avoiding the locations and institutions they associated with their experience of stigma [30,33]. This can be problematic because avoiding medical offices and clinics, social services, and school can put adolescent mothers at greater risks for repeat births and delinquent behaviors.

A growing body of research now examines effective strategies to address stigma, with the goal of improving health and well-being for individuals in stigmatized groups. Broadly, stigma-reduction interventions are characterized by (1) their use of empowerment frameworks [which re-direct the power imbalance inherent in the process of stigma] and (2) their focus on multiple levels of society (e.g., individual, interpersonal, community, institutional, policy) to address the process in which stigma is created and perpetuated in society [9]. These characteristics are important from a public health perspective because, unlike intervention strategies directed at the individual level, these strategies avoid victim-blaming and attempt to address fundamental causes of persistent health disparities. Despite these promising developments, the majority of theories used to develop and implement evidence-based programs for pregnant and parenting adolescents are limited to proximal determinants (e.g., birth control, school enrollment, goal setting). Future interventions aiming to be established as evidence-based may find benefit in exploring the impact of intersectional stigma theory on the social processes (e.g., self and friends/family/teacher/health providers’ acceptance of adolescent mothers’ pregnant body and intersecting role as an adolescent and mother) adolescent mothers encounter as they transition to and navigate within adolescent motherhood. In effort to better address social injustices experienced by adolescent mothers and their children, such programs may include components directed at individual adolescents (e.g., advocacy, skills development, knowledge of birth control methods), health care and social service providers (creation of adolescent-friendly services, access to transportation, free birth control services, trainings for health care and social service providers), and communities (e.g., building and supporting community networks, creating safer environments, increase community resources).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tracy Nichols, PhD, of the Department of Public Health Education at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro for her formative feedback and editorial assistance.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2015) About Teen Pregnancy.

- SmithBattle L (2012) Moving policies upstream to mitigate the social determinants of early childbearing. Public Health Nurs 29: 444-454.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2013) Vital signs: Repeat births among teens - United States, 2007-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 62: 249-255.

- Olds DL, Henderson CR Jr, Tatelbaum R, Chamberlin R (1988) Improving the life-course development of socially disadvantaged mothers: a randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Am J Public Health 78: 1436-1445.

- SmithBattle LI (2013) Reducing the stigmatization of teen mothers. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 38: 235-241.

- Goffman E (1963) Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity.

- Jones E, Farina A, Hastorf A, Markus H, Miller DT (1984) Social Stigma: The Psychology of Marked Relationships. New York, NY: Freeman and Company.

- Stafford MC, Scott RR (1986) “Stigma deviance and social control: Some conceptual issues.” In The Dilemma of Difference: A Multidisciplinary view of stigma. New York: Plenum.

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C (1998) Social stigma. In The handbook of social psychology. (4th edn.), New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Link BG, Phelan JC (2001) Conceptualizing stigma. Annual review of Sociology 363-385.

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG (2013) Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health 103: 813-821.

- Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR (2011) HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med 8: e1001124.

- Crenshaw KW (1989) Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chic Leg Forum, 139:139-167.

- Crenshaw KW (1991) Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241-1299.

- Bowleg L (2012) The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality- an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. Am J Public Health 102: 1267-1273.

- Berger MT (2004) Workable sisterhood: The political journey of stigmatized women with HIV. Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey pp: 234.

- Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR (2013) Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol 68: 225-236.

- Mill J, Edwards N, Jackson R, Austin W, MacLean L, et al. (2009) Accessing health services while living with HIV: intersections of stigma. Can J Nurs Res 41: 168-185.

- Furstenberg FF (2007) Destinies of the disadvantaged: The politics of teenage childbearing. New York: Russell Sage Foundation 54:15.

- Weiner LY (1994) Reconstructing motherhood: the la leche league in postwar America. The Journal of American History 80: 1357-1381.

- Rolfe A (2008) 'You've got to grow up when you've got a kid': Marginalized young women's accounts of motherhood. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 18: 299-314.

- Tiefer L (2006) Female sexual dysfunction: a case study of disease mongering and activist resistance. PLoS Med 3: e178.

- Luker K (1996) Dubious conception: the politics of teenage pregnancy. Harvard University Press.

- Burt MR (1990) Public costs and policy implications of teenage childbearing. AdvAdolesc Mental Health 4: 265-280.

- Fielding JE, Williams CA (1991) Adolescent pregnancy in the United States: a review and recommendations for clinicians and research needs. Am J Prev Med 7: 47-52.

- Dorrell LD (1994) A future at risk: children having children. Clearing House 67: 224-227.

- Kirby D (1999) Reflections on two decades of research on teen sexual behavior and pregnancy. J Sch Health 69: 89-94.

- History- Brown v. Board of Education Re-enactment.

- US Employment Opportunity Commission (1978) The Pregnancy Discrimination Act.

- Fulford A, Ford-Gilboe M (2004) An exploration of the relationships between health promotion practices, health work, and felt stigma in families headed by adolescent mothers. Can J Nurs Res 36: 46-72.

- Gregson J (2009) The culture of teenage mothers. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Higginbottom GM, Mathers N, Marsh P, Kirkham M, Owen JM, et al. (2006) Young people of minority ethnic origin in England and early parenthood: views from young parents and service providers. SocSci Med 63: 858-870.

- Yardley E (2008) Teenage mothers’ experiences of stigma. Journal of Youth Studies 11: 671–684.

- National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancies [NCPTUP]. (2013) Counting It Up: The Public Costs of Teen Childbearing.

- Guglielmo L (2013) MTV and Teen Pregnancy: Critical Essays on 16 and Pregnant and Teen Mom. Scarecrow Press.

- Kearney MS, Levine PB (2014) Media influences on social outcomes: the impact of MTV's 16 and pregnant on teen childbearing. National Bureau of Economic Research, w19795.

- Wiemann CM, Rickert VI, Berenson AB, Volk RJ (2005) Are pregnant adolescents stigmatized by pregnancy? J Adolesc Health 36: 352.

Relevant Topics

- Adolescent Anxiety

- Adult Psychology

- Adult Sexual Behavior

- Anger Management

- Autism

- Behaviour

- Child Anxiety

- Child Health

- Child Mental Health

- Child Psychology

- Children Behavior

- Children Development

- Counselling

- Depression Disorders

- Digital Media Impact

- Eating disorder

- Mental Health Interventions

- Neuroscience

- Obeys Children

- Parental Care

- Risky Behavior

- Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Societal Influence

- Trauma-Informed Care

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 20721

- [From(publication date):

October-2015 - Jul 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 15747

- PDF downloads : 4974