Research Article Open Access

The Prevalence and Impact of Invasive Procedures in Women with Gynecologic Malignancies Referred to Hospice Care

Jessica E. Stine1*, Kemi M. Doll1, Dominic T. Moore2, Linda Van Le1,2, Emily Ko1,2, John T. Soper1,2, Daniel Clarke-Pearson1,2, Victoria Bae-Jump1,2, Paola A. Gehrig1,2 and Kenneth H. Kim1,21Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA

2Lineberger Clinical Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC

- *Corresponding Author:

- Jessica E. Stine, M.D.

Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center

Obstetrics and Gynecology, Campus Box 7572

Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7572, USA

Tel: 919-966-5996

Fax: 919-843-5387

E-mail: jstine@unch.unc.edu

Received date: February 21, 2014; Accepted date: April 15, 2014; Published date: April 26, 2014

Citation: Stine JE, Doll KM, Moore DT, Le LV, Ko E, et al. (2014) The Prevalence and Impact of Invasive ProceduresinWomen with Gynecologic Malignancies Referred to Hospice Care. J Palliat Care Med 4:175. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000175

Copyright: © 2014 Stine JE, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Objective: To determine the prevalence of inpatient invasive procedures performed in patients who had been referred to hospice and to evaluate the impact of the procedures on end of life (EOL) treatments and outcomes.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of gynecologic oncology patients who were discharged from the hospital to hospice care from January 2009 – June 2012, comparing those who had invasive procedures (PRO) to those who did not (NOPRO), was conducted. Clinical data included disease site and stage, course of admission, type of hospice chosen, administration of palliative chemotherapy or radiation, hospital readmissions and number and type of invasive procedures performed. Overall survival was defined as the time from the date of hospice referral to death from any cause.

Results: Eighty-eight patients were identified and the majority (46%) had ovarian cancer.Sixty-five percent (57/88) of patients had invasive procedures (PRO) in the 4 weeks prior to hospice enrollment. There was no difference in PRO vs. NOPRO groups with respect to palliative chemotherapy (91.3% vs. 83%, p=0.48) or radiation treatments (8.7% vs. 16.1%, p=0.31), the proportion of patients choosing inpatient hospice care (21% vs. 22.5%, p=0.87) or hospital readmissions (10.5% vs 9.3%, p = 1.00). Overall survival was not significantly different between the groups (56d vs 54d, p=0.71).

Conclusions: The relationship between PRO and NOPRO during EOL care did not adversely affect palliative treatment delivery, hospital re-admission rate, home vs. inpatient hospice decision or overall survival. Caution should be exercised when determining the need for invasive procedures in the palliative setting.

Keywords

Hospice; Invasive procedures; Palliative care

Introduction

Gynecologic malignancies will account for approximately 28,080 deaths in the United States in 2013 [1]. Ovarian cancer contributes to the majority of deaths with a projected 14,030 [1]. Given these statistics, a key role of the gynecologic oncologist is that of a physician who cares for patients at the end of life (EOL). The utilization of hospice care in the United States in oncologic patients has more than doubled from 540,000 in 1998 to 1,300,000 in 2006 according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology [2]. This may be reflective of the society’s endorsement of the early use of palliative care services with advanced or symptomatic disease [3]. With this trend, more literature has been dedicated to discussing hospice care in the gynecological oncology patient population [4-12]. The goal of hospice is to provide compassionate, holistic care for patients and their families and to maximize quality of life through a variety of methods [13].

A retrospective study by Keyser et al. found that gynecologic oncology patients who were not enrolled in hospice at the end of life were more than two times more likely to have medical or surgical interventions for symptomatic relief or to prolong life performed within four weeks of their death [8]. Despite these findings, a large part of palliative care involves invasive procedures ranging anywhere from 30-60% in this patient population [4,8]. Common invasive procedures in the gynecologic oncologic patient population include paracentesis, thoracentesis, gastric tube placement, catheter and drain placements and even major surgery for the purposes of symptomatic relief [4]. Physicians struggle with an ongoing dilemma regarding futility of certain aspects of care, particularly continuing invasive interventions [4]. Despite this important question, there is limited data that addresses the issue of preforming interventions on hospice patients and the impact this may cause. The literature remains inconclusive regarding the benefit of invasive procedures on symptomatic control, quality of life and overall survival.

Although patients may enter into hospice from the outpatient setting, there are a group of patients that are discharged to hospice care following an inpatient hospitalization. Inpatient stays present opportunities for palliative care consultations and discussions with the primary provider regarding goals of treatment [14]. The current study seeks to describe the utilization of invasive procedures on hospice patients referred from the inpatient setting in the 4 weeks prior to referral, and evaluate if these interventions have an overall positive or negative effect on several aspects of delivery of palliative care and their impact on overall survival.

Materials and Methods

After IRB approval from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (#12-1608), we performed a retrospective cohort analysis of gynecologic oncology patients who were discharged from the hospital directly to either inpatient or outpatient hospice care from January 2009-June 2012. Patients enrolled in hospice priorto admission were excluded. The patients were identified via a hospice enrollment database kept by the inpatient social worker. Demographic data included age, race, and dates of death. The social security database was queried to determine the date of death.

Clinical data extracted included disease site and stage, clinical course of admission and reason for admission, hospice type chosen, treatment with palliative chemotherapy or radiation in the 8 weeks prior tohospice referral and hospital readmissions. When there were multiple indications for admission, the primary indication was determined based on the patient’s clinical documentation. The number and type of invasive procedures performed in the 4 weeks before referral including those at the time of inpatient hospitalization were recorded. Invasive procedures were defined as any procedure requiring local or systemic anesthesia. These included laparotomy, ostomy, percutaneous nephrostomy tube placement, gastric tube placement, paracentesis, thoracentesis, radiology guided biopsies and drains, port-placements and embolizations. The procedure (PRO) and nonprocedure (NOPRO) groups were compared.

Statistical methods

Cox regression modeling was used to explore the association of selected covariates of interest on the time-to-event outcome of overall survival (OS). Overall survival for this study has been defined as the time from the date hospice discharge to death from any cause. For models of interest, relevant hazard ratios (HR) with their 95% confidence intervals have been given.

An approximation to Bayes factors, known as the Schwartz Bayesian Criteria (SBC), were used to assess the strength of evidence of association for each covariate of interest on the time-to event function of OS [8,9]. The SBC, in the form of a ‘difference measure’, may be much more useful than a ‘traditional’ interpretation of a ‘p-value < 0.05’ for two main reasons. The first is that using the difference in SBCs can give information in support of the null hypothesis. The second is that the difference in SBCs may be more ‘interpretable’ in either very large or very small sample sizes (where an alpha level of 0.05 has less of an ‘interpretative value’). When comparing differences in SBC, the following measures of the degree of evidence can be used: 0 to 2 is considered ‘weak’, greater than 2 and up to 6 is ‘positive’, greater than 6 and up to 10 is ‘strong’ and 10 or greater is considered ‘very strong’. Negative analogs of these numbers provide the same information in support of the null hypothesis.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate OS and the logrank test was used to test for significant differences. Fisher’s exact test was used to test for significant differences between two-group and/ or nominal categorical variable comparisons. The nonparametric Jonckheere-Terpstra method was used to test for significant differences across ordered categories for contingency tables where at least one of the variables was ordinal, and had at least 3 categories. With this test, the null hypothesis is that the distribution of the response does not differ across ordered categories. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test (using Van der Waerden normal scores) was used for continuous variables undergoing two-group comparisons. Monte Carlo estimates for exact p-values have been reported. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, Version 9.2, from the SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC.

Results

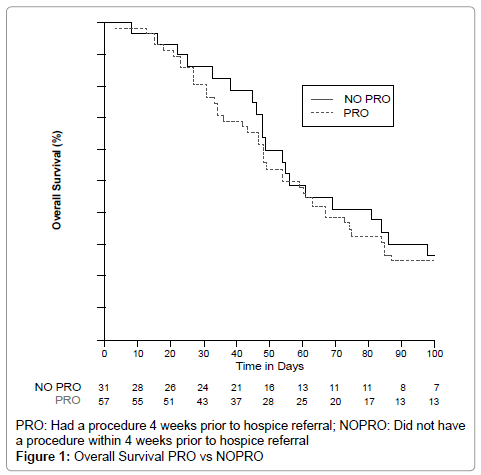

Eighty-nine inpatient hospitalizations of gynecologic oncology patients resulted in referral to hospice. Eighty-eight patients were identified that had available procedural data to analyze. The demographics and tumor characteristics are described in Table 1. There was no difference between the two groups in regards to age (p=0.99) or race (p=0.99). There were 41 women with ovarian cancer (46%), 23 with uterine (26%), 19 with cervical (22%), and 5 vulvar or vaginal (6%) cancers. Sixty-five percent (57/88) of patients had invasive procedures (PRO) within 4 weeks of hospice referral, while 31/88 (35%) did not. The exact procedures performed are displayed in Table 2. Seventeen patients received 2 or more procedures. The most common procedure performed was gastric tube placement for obstructive symptoms. There were a higher proportion of patients with ovarian cancer in the PRO group (p=0.02). There was no difference in the PRO vs. NOPRO patient groups with respect to receiving palliative chemotherapy (91.3% vs. 83%, p=0.48), radiation treatments (8.7% vs. 16.1%, p=0.31) or palliative care consultation (75% vs. 59%, p=0.22). There was also no difference in the proportion of patients electing for inpatient hospice care (21% vs. 22.5%, p=0.87) or hospital readmissions after hospice referral (10.5% vs 9.3%, p=1.00) [Table 3]. Overall survival was not significantly different between PRO and NOPRO (56d vs 54d, p=0.71) (Figure 1).

| N=88 (%) | PRO N=57 | NOPRO N=31 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean | 62 | 63 | 0.99 |

| Range | (30-84) | (31-88) | |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 38 (67) | 22 (71) | 0.99 |

| African American | 15 (26) | 8 (26) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.75) | 1 (3) | |

| Asian | 1 (1.75) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 1 (1.75) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.75) | 0 (0) | |

| Cancer type | |||

| Ovarian | 32 (56) | 9 (29) | 0.02 |

| Uterine | 14 (25) | 9 (29) | |

| Cervical | 7 (12) | 12 (39) | |

| Vulva/Vaginal | 4 (7) | 1 (3) | |

PRO: Had a procedure 4 weeks prior to hospice referral; NOPRO: Did not have a procedure within 4 weeks prior to hospice referral

Table 1: Patient Demographics.

| Types | N=57 |

|---|---|

| Percutaneous nephrostomy tubes | 8 |

| Gastric tube | 22 |

| Laparotomy | 12 |

| Ostomy | 4 |

| Paracentesis | 9 |

| Thoracentesis | 5 |

| Radiology guided drain placement | 14 |

| Port placement | 1 |

| Embolization | 3 |

| Other | 7 |

*Performed 4 weeks prior to hospice referral

Table 2: Invasive procedure.

| PRO N=57 (%) | NOPRO N=31 (%) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palliative Chemotherapy given | |||

| Yes* | 52 (91.3) | 26 (83) | 0.48 |

| No | 5 (8.7) | 5 (17) | |

| Radiation given | |||

| Yes | 5 (8.7) | 5 (16.1) | 0.31 |

| No | 52 (91.3) | 26 (83.9) | |

| Hospice type | |||

| Inpatient | 12 (21) | 7 (22.5) | 0.87 |

| Home | 45 (79) | 24 (77.5) | |

| Hospital readmissions | |||

| Yes | 6 (10.5) | 3 (9.3) | 1.0 |

| No | 51 (89.5) | 28 (90.7) | |

| Overall survival (d) | 56 days | 54 days | 0.71 |

| *Palliative chemotherapy received 8 weeks prior to hospice referral PRO: Had a procedure 4 weeks prior to hospice referral; NOPRO: Did not have a procedure within 4 weeks prior to hospice referral | |||

Table 3: PRO vs NOPRO.

Kaplan-Meier curve comparing PRO vs. NOPRO groups. Procedures do not appear to prolong or shorten overall survival in the terminal stages of gynecologic cancer.

Discussion

Our study has concluded that the relationship between PRO and NOPRO during EOL care did not adversely affect palliative treatment delivery, hospital re-admission rate, home vs. inpatient hospice decision or overall survival. There is no question that the study of palliative care and hospice is of growing interest in the field of gynecologic oncology. Currently, available literature hastypically extracted all deceased patients and then compared those who did or did not use hospice care [4-8]. Of these, there are a few that addressed procedures.Keyser et al. in 2010 concluded that patients not on hospice were more likely to undergo invasive procedures 55% versus 31% [8]. The most common invasive procedures were paracentesis, gastrostomy tube placement and surgery. The most recent publication by Fauci et al. examined the use of palliative care services in the last six months of life [4]. They concluded that 71.2% of patients underwent treatment with chemotherapy or radiation in the last six months of life and 58.6% had a procedure performed during that time. When they reviewed patients that were subsequently enrolledin hospice, only 3.2% had any therapy; however 55% of patients were enrolled in hospice for less than 30 days. The most common procedure performed was again paracentesis followed by surgery and intravenous port placements. The majority of patients received a mean of 1 procedure ranging from 0-11 [4]. Both studies did not appreciate a difference in survival between the hospice and non-hospice groups.

Unlike previous literature, this studyfocuses solely on patients referred to hospice in order to understand whether procedural interventions affect their overall survival and secondary outcomes. To our knowledge there has not been a study to compare the impact of procedures on survival or disposition amongst newly referred hospice patients that have or have not received invasive procedures in the 4 weeks prior to hospice enrollment. Our patients most commonly received 1-2 procedures. The most frequent procedures were gastrostomy tube placement, image-guided drain placement, or surgery. This is consistent with previous literature [4,8].

In this study, patients were able to receive palliative radiation and/or chemotherapy in both the PRO and NOPRO groups. This information may be reassuring to practitioners that might feel that having procedures performed may delay these palliative treatments. In addition, patients in the PRO group were not more likely than the NON-PRO group to be admitted toinpatient hospice care. The decision to enter home versus hospital-based hospice was likely more dependent on other external factors not evaluated in this study. Lastly, overall survival was not significantly different between the groups at 56d in the PRO group vs 54d in the NONPRO group (p=0.71).

There are several ways to interpret this data. First, procedures do not appear to prolong or shorten overall survival in the terminal stages of gynecologic cancer. One could argue that these interventions may be improving the quality of life for our hospice patients, but this data was not collected in this study. Intuitively, some more minor procedures such as paracenteses to relieve pressure from ascitic fluid or an ostomy to relieve the symptoms of a small bowel obstruction could be helpful in contrast to larger more invasive procedures. This would be an important focus of future research to determine if our interventions are helpful. A comparison of minor versus major procedures could also be helpful.

Our study is limited by sample size and its retrospective nature. We did not have the ability to collect quality of life data. We know that procedures do not affect the choice between inpatient versus outpatient hospice, but we do not have additional information on the patient’s decision-making process. Though difficult to perform, acontinuous prospective collection of patient centered outcomes data focusing on quality of life and survival in this setting would further develop our understanding of the impact of invasive procedures and palliative treatment with either chemotherapy or radiation towards the EOL. The decision for performing invasive procedures should be made based on a case by case basis, taking into account the individual patient’s symptoms and goals of care.

Essential points

Invasive procedures during hospice care did not adversely affect palliative treatment delivery, hospital re-admission rate, home vs. inpatient hospice decision or overall survival.

References

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2013) Cancer statistics 2013. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. Vol 63: 11-30.

- Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, Cummings C, Currow D, et al. (2009) Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps -- from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J ClinOncol 27: 3052-3058.

- Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, et al. (2012) American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J ClinOncol 30: 880-887.

- Fauci J, Schneider K, Walters C, Boone J, Whitworth J, et al. (2012) The utilization of palliative care in gynecologic oncology patients near the end of life. GynecolOncol 127: 175-179.

- Cain J, Stacy L, Jusenius K, Figge D (1990) The quality of dying: financial, psychological, and ethical dilemmas. ObstetGynecol 76: 149-152.

- Dalrymple JL, Levenback C, Wolf JK, Bodurka DC, Garcia M, et al. (2002) Trends among gynecologic oncology inpatient deaths: is end-of-life care improving? GynecolOncol 85: 356-361.

- Fairfield KM, Murray KM, Wierman HR, Han PK, Hallen S, et al. (2012) Disparities in hospice care among older women dying with ovarian cancer. GynecolOncol 125: 14-18.

- Keyser EA, Reed BG, Lowery WJ, Sundborg MJ, Winter WE 3rd, et al. (2010) Hospice enrollment for terminally ill patients with gynecologic malignancies: impact on outcomes and interventions. GynecolOncol 118: 274-277.

- Chase DM, Monk BJ, Wenzel LB, Tewari KS (2008) Supportive care for women with gynecologic cancers. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 8: 227-241.

- Miller BE, Pittman B, Strong C (2003) Gynecologic cancer patients' psychosocial needs and their views on the physician's role in meeting those needs. Int J Gynecol Cancer 13: 111-119.

- Rezk Y, Timmins PF 3rd, Smith HS (2011) Review article: palliative care in gynecologic oncology. Am J HospPalliat Care 28: 356-374.

- Doll KM, Stine JE, Van Le L, Moore DT, Bae-Jump V, et al. (2013) Outpatient end of life discussions shorten hospital admissions in gynecologic oncology patients. GynecolOncol 130: 152-155.

- von Gruenigen VE, Daly BJ (2005) Futility: clinical decisions at the end-of-life in women with ovarian cancer. GynecolOncol 97: 638-644.

- Rocque GB, Barnett AE, Illig LC, Eickhoff JC, Bailey HH, et al. (2013) Inpatient hospitalization of oncology patients: are we missing an opportunity for end-of-life care? J OncolPract 9: 51-54.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14037

- [From(publication date):

April-2014 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9530

- PDF downloads : 4507