The Level of Education of Women Residing in the Parish of Angochagua-Ibarra and its Effect in the Sexual and Reproductive Health

Received: 22-Nov-2017 / Accepted Date: 21-Dec-2017 / Published Date: 26-Dec-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000576

Abstract

Due to the education has a fundamental role as base of knowledge and allows the development of skills which empower men, women and adolescents in decisions making and responsibility of health, it is relevant the education in health in alternative scope which offers the option to choose patterns and behaviors, related to its particular form to interpret the sexuality, realigning the individual with the social and broaden it without antagonistic conflicts.

Objective of study: To establish the relation between the educational level of women who live in Angochagua parish from Ibarra-Ecuador and its incidence in their sexual and reproductive health.

Materials and methods: It is a non-experimental qualitative design of observational, descriptive and transversal type where women from 15 to 61 years were included who lived in the area where the study was conducted and whom after a previous authorization was applied a survey.

Results: It was evident a directly proportional relation between literacy and access to programs of health care, a high rate of pregnancies in young, unmarried women, a high rate of children and deceased children from early ages in women with low level of education. The 90% of investigated women from 45 to 61 years who live in the rural areas which were studied did not enter in the school and they do not read nor write, as a result, due to lack of educational level affected in their reproductive life with more children.

Conclusion: The young women with higher educational levels have limited knowledge of sexual and reproductive health and although their condition related to older women and less educated has improved, the rural woman is discriminated too as a person, and it is unknown her universal right of health care.

Keywords: Instruction; Health; Sexuality; Reproduction

Introduction

The importance of studying social and cultural patterns is based on the specificity of the Latin American context in reproductive and sexual matters. Thus, it can be estimated that when a generalized increment in fertility in peasant women is observed decreasing in the last decades and its relative contribution has remained constant or has been increasing, what happens in spite of the massive diffusion of the contraceptives. This paradox transforms the right to education in rural women is necessary and imminent.

The wealth of the human being deserves that certain concepts such as freedom, sexuality, love, procreation, marriage and family are considered in their whole integrity. It is not the individual person, not even a certain culture or society that has to "interpret" the meaning of sexuality, but it must be considered in light of certain imprescriptible and inalienable sociological, anthropological and ethical principles. It is unknown from the past till now that exists a definite position on the elements through the educational level influences the sexual health and fertility in rural women. However, over the years studies on this scope have shown that women with approved years in schooling are one of the most important social factors that demonstrate reproductive behavior [1].

Around the world the degree of education is associated with the size of the family, the greater one is the least the other. In a number of least developed countries, women without education have almost twice more children than women with ten or more years of schooling. The woman with more education usually shows a later and healthier transition to the adult stage of her life.

She has her first sexual intercourse later, marries later, wants to have a smaller family, and is more likely to use contraception than others less educated women. Chevarria points out that "the decisive factor of fertility is the educational level of women, education is thus a facilitator of access to information and the means required for its regulation [2]. Related to religion and behavior within homes, these are determinants in the allocation of time, to be associated with certain behaviors, customs and lifestyles, materialized in the attribution of roles by genders, and in the definition of the place that the family takes in the society, this has repercussions in the decisions of the number of children, the formation of households [3].

Paz points out that "the existence of the relation between education and fertility has been widely recognized and verified through various demographic studies in developing countries; empirical studies have demonstrated the existence of an inverse relationship between these two variables; in other words, women with higher levels of education have fewer children than those without education" [4].

From this perspective it is important to incorporate the relation established by social determinants in policies aimed at promoting healthy development; we can simplify that, in order to reduce poverty, it is relevant to promote access and permanence in the educational scope and the inalienable access to health services, to demand the inclusion of rural women in stable educational programs, strategies to support definition of a public social policy and, in general, to promote positive aspects for development.

These policies should consider changes that are occurring at the structural level, such as the lack of programs of sexual and reproductive education, which are lived in unprotected societies such as the one investigated. Those changes can permeate the most immediate decisions, even the reproductive ones, or limit the opportunities of the peasant women. For this reason, it is fundamental to take advantage social programs as a model to promote reproductive health actions in women.

It is necessary, then, to recognize that educational formation creates awareness and forms clear ideas about sexuality and reproduction, also in those cases where it considers it as a personal and private matter, and relative to the world of reproductive health, in the ideological cultural pattern of rural women is lower and male thinking is the sole responsible, hence defining the identity of the woman being a factor that affects the reproductive behavior of women especially in younger, and these therefore change the composition and social structure of the parish.

Enlarged families make greater differences in areas where woman face higher fertility rates and the number of dependents is higher. For this reason, it is recommended that employment policies that focus on reducing barriers to access women in the labor market are particularly concerned with the poorest women, including mechanisms that reduce the influence of factors associated with the decision to have children as family planning mechanisms, childcare provision and fairness in the distribution of household chores [5].

Reproductive sexual education in the subject of educational instruction appears as a topic from which state policies must begin to work. However, the educational insertion affects the ideological formation of aspects of sexuality. At the time, these behaviors were expected and secondary to a young lady and were necessary and important for a man.

It is clear that today sexual and reproductive health centers in different ways in educational training, primarily because it has another place in society. What is expressed implies to carry out the present investigation to help think about the best ways in which educational instruction can accompany and promote the development of sexual education, not only focused on prevention and medical control but understanding it as an important component for a full life and to improve the quality of life of women.

Objective

To establish the relationship between educational instruction and the incidence of sexual and reproductive health.

Methodology

It is a non-experimental, qualitative, observational, descriptive, and cross - sectional design study. The universe of study was confirmed by fertile women and older adults than live in the communities Magdalena, Culebrillas, Sigsaloma, La Rinconada, Zuleta and Cochas belonging to the Angochagua parish. The method is a simple random sampling, in which were taken 124 women from Angochahua parish, the first group of sixty-two women between the ages of 15 to 30 years, and the second group of sixty-two women that includes women from 46 to 61 years of age, the women selected to this study had the following characteristics of inclusion: mothers, married, divorced, or mothers heads of households. It is important to indicate that women agree to participate voluntarily in this research in, focus groups and surveys as well as instruments designed for the purpose. The data tabulation was performed through a statistical program for their respective analysis.

Discussion

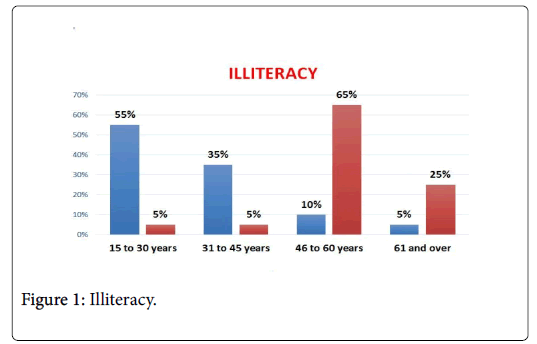

Statistically relating the variables fecundity and education, 90% of the women surveyed from 45 to 61 years of age living in the rural area studied, they did not enter school and do not know how to read or write, especially women from 61 years do not know how to write nor their names, therefore in low educational level had an impact on having more children with an average of 7 children, the group of women who are in the 45-61 years and who have an intermediate fertility had from 4 to 7 children (Figure 1).

It was shown that 94.6% of women who entered school between 15 and 45 years old, the birth rate is smaller, that is, they had between 1 and 2 children, showing a low fecundity.

Most of the women surveyed did not attend school or high school, and almost all of them lacked public health coverage, evidencing the lack of social work. The antecedent of poverty in the communities has a strong effect on the culture of adolescent pregnancies in contexts of poverty; teenage pregnancy is a very common trigger that is caused by a number of social and cultural factors that are directly linked to the lack of education and especially with the lack of contraceptive use (Table 1).

| Years | Health Care Center | Care with Midwives | Know Sexual and Reproductive Health | Uses Contraceptive Methods | Number of children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15-45 years | Yes | 20.9 | 29.2 | 14.9 | 33.9 | 1-2 Children |

| No | 29.2 | 20.9 | 35.1 | 16.1 | ||

| 46-61 years | Yes | 12.5 | 37.5 | 6.3 | 10 | 4 to 6 children |

| No | 37.5 | 12.5 | 43.8 | 40 | ||

Table 1: Statistically relating the variables fecundity and education.

It is stated that the existence of an intrinsic relation between education and conception of children (reproduction) and the sexual and reproductive health of the natives is presented only from the western point of view; only a limited number of intermediaries are aware of sexual and reproductive health practices or the indigenous worldview. As indicated by Cheverria in her study in the same that establishes that the woman with more education usually makes a later and healthier transition to the adult stage of her life. She has her first sexual intercourse later, marries later, wants to have a smaller family, and is more likely to use contraception than other less educated women [1].

It is possible to indicate that in this investigation the results obtained coincide with the conception of Chevarria, since the investigated women who presented the highest level of schooling are the ones with the lowest number of children as detailed in the table described. What is needed is the cultural pattern in which the importance of educational training still exists in the communities investigated, framing the baron the decision of the number of children to have.

It is not known that there is still a definite position on the elements through which the educational level influences the sexual health and fertility of rural women, however, over the years studies carried out in this area have shown that women with approved years, are one of the most relevant social factors that evidence reproductive behavior. As evidenced by the study of indigenous women reproductive health and community organization held in Santiago de Chile by the United Nations in 1998 [2].

Regarding pregnancy control in women aged 15 to 45, 20.9% go to the health center, 29.2% are controlled by the midwife and give birth at home. In women between the ages of 46 and 61, 12.5% reported having attended the Ibarra health center and 37.5% attended the midwife (a considerable difference compared to younger women). However, 15% of women between the ages of 45 and 61 have schooling and they were never monitored during pregnancy. The women of the two groups who controlled their pregnancy in the Health Center, did not go to this health post to give birth, they preferred to have their baby at home, attended by the midwife or close relatives, due to their customs, cite illustrative way to give birth in squatting.

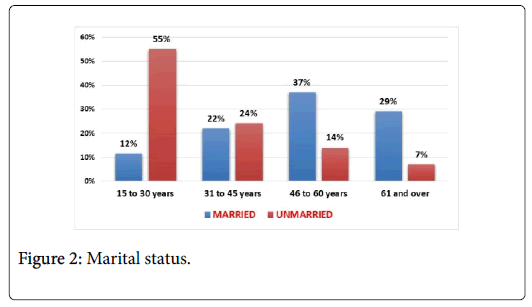

The data obtained in this research marked a considerable difference in the conception of the number of children and the controls of the pregnancy, evidencing that the women are unaware of the importance of receiving a birth control by health specialists, as shown by Paz in which he points out that "the existence of the relationship between education and fertility has been widely recognized and verified through various demographic studies in developing countries (UN 1983) [4]. It is thus concluded that marked reductions in fertility often occur among women who have had six or more years of schooling (Figure 2).

According to FLACSO 2010 studies among the rural popular sectors of the highland region and the peasantry, if couples cohabit, this usually entails a formal marriage. The vast majority of marriages that are celebrated are only civil marriages, that is, they are not always followed by a religious ceremony.

Within the age range of 31-45 years, married marital status prevails in 22%, from 46 to 60 years old corresponds to 37% and the group of 61 and older are mostly married in 29%. It should be noted that the age group of 15 to 30 years only 12% are married and a considerable 55% is not. This is a phenomenon that must be understood first from the industrial transformations that have affected to diminish marriages, since in rural and agrarian areas families neglected the educational training of their daughters, prioritizing more their workforce for work in the home and the field (Figure 3). At present, this has diminished due to the replacement of the labor force by the machine and the remarkable access of this age group to an education, only a minimum 5% has illiteracy, therefore, the dynamics of women's thoughts and conceptions have changed in rural areas, giving priority to other aspects of marriage, such as study, vocational training and personal fulfillment.

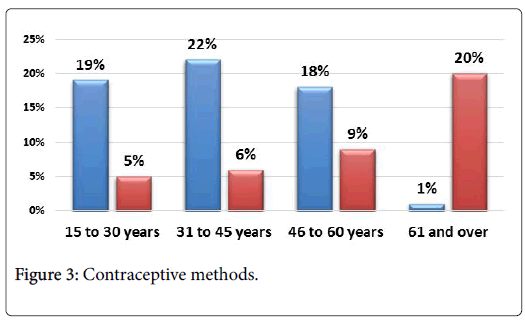

Contraception is not an independent or optional issue, but is part of the integral health of women and men. 40% of women aged 15-45 used contraception and women aged 46-61 in 29% said that did not use methods. This data agrees with the second volume of the National Survey of Health, Nutrition, Sexual and Reproductive Health (Ensanut). The results showed that Ecuador is different today: there are fewer children per woman and they already make decisions about contraceptive methods to use. It is important to emphasize that, in rural areas, the ligature, as well as the choice of any contraceptive method was 'consulted' to the husband or partner, this situation has changed and now the woman is the one who decides. In the Angochagua area, it was shown that women have access to and information on contraceptive methods through health and education services, focusing on their fertility and the birth rate that in recent years has declined in rural areas (Figure 4).

Access to information and family planning services is currently accepted in the community of Angochagua in the generation of 15 to 45 years, as opposed to the group of 45 to 61 years. This factor is categorized as a basic human right, which allows women to make their own decisions regarding reproduction; the denial of this right for different ideological reasons is an ethical issue that must be discussed with full respect for the diversity of sociocultural and individual visions present in each society

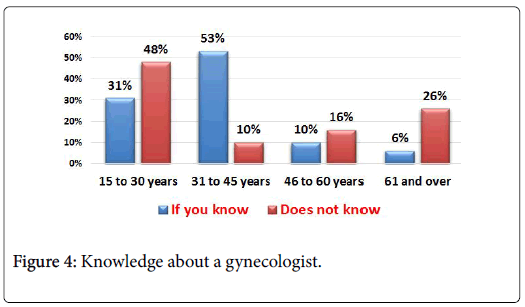

The perception of women's health as a factor of social vulnerability has led Latin American countries to adopt policies aimed at improving access to gynecological medical services, designing projects that allow women's needs to be addressed. 84% of women aged 15-45 know what gynecological care is, but 42% of women aged 46-61 have never heard of a gynecologist.

The marginalization of the health system coincides with a characteristic of rural poverty, which presents more difficulties than in urban poverty for the provision of gynecological services, although women in rural areas can access gynecological care through an obstetrician at a health center to perform check-ups on topics related to family planning or pap test, access to mammograms or ultrasounds are examinations not accessible due to the lack of equipment of health care services in rural geographic areas such as the case of the community of Angochagua.

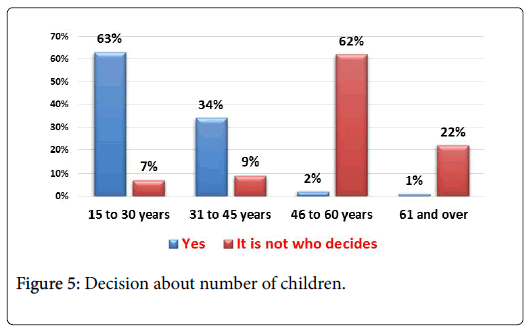

The responsibility of the administration of family health in the community of Angochagua is granted to the mother, who plays a fundamental role because culturally for women's health issues, she goes to the midwife or healer, considered in Ecuador as a type of ancestral and alternative medicine; the same that is accepted and respected by the community of Angochagua especially by the age group of women from 46 to 61 years. These women constitute a group of patients who are not very demanding and informed according to the staff of the health center, do not have internet or specialized press so they cannot claim other forms of care and mainly the figure of the doctor creates an image of insecurity unlike the midwife or healer of the community. In a generational group of women aged 15 to 45 years, if an informed approach in registered medical care is reported in the community health center (Figure 5).

97% of women aged 15-45 indicate that they decide the number of children to have, and 84% of women aged 46-61 never decided the number of children to conceive.

In another consideration it is concluded that the limited profile of schooling, prevents women from entering and joining a qualified and better paid job, are employed or required for tasks not qualified as milkers or cooks, because their clothing is located in low-level jobs, where they are often exploited and violent in their rights, as manifested Yanez M, in his research in the Caribbean Coast and Colombia which he states that the school always has a positive and significant impact on the probability of participating in the labor market. At the same time, age also has a positive impact; although unlike women with children is not significant [5].

The indigenous woman of the parish investigated does not have and has not had the possibility of equal access to educational and training programs, the low educational level, had a direct impact on their low valuation and acceptance as a participatory and decisive body in a social environment [6-9].

Conclusions

The present study shows that the women from Angochagua parish presents:

• It is a female population, the age between 15 and 61 years; which self-defined as indigenous, within the age range of 31 to 45 years shows that married civil status prevails in 22%, from 46 to 60 years corresponds to 37% and the group of 61 and older are mostly married in a 29%. It should be noted that the age group of 15 to 30 years only 12% are married and a considerable 55% are unmarried.

• A 90% of women surveyed from 45 to 61 years old did not go to school and do not know how to read or write, especially women of 61 years do not know how to write their names, so the low educational level had an impact on having more children with an average of 7 children, the group of women who are between 45 and 61 years of age and who have an intermediate fertility have 4 to 7 children.

• A 94.6% of women entering the school between 15 and 45 years old, the birth rate is reduced between 1 and 2 children, showing a low fertility, only a minimum of 5% have illiteracy, it is clear that it has changed the dynamics of thoughts and conceptions of women in rural areas, prioritizing other aspects of marriage such as study, vocational training and personal fulfillment.

• Related to pregnancy control in women aged 15-45, 20.9% go to the health center, 29.2% are controlled by the midwife and give birth at home; this group of women constitute a group of patients who are not very demanding and informed by the staff of the health center, do not have internet or specialized press and therefore cannot claim other forms of care.

• Once the research is concluded, it can be determined that the needs perceived by the participating women are related to the fact that the sexual education received in their homes is scarce in information and the very inadequate form of transmition. They point out that personalized and continuous education and the use of educational technologies are part of their expectations of sexual and reproductive health learning.

• In women between the ages of 46 and 61, 12.5% said they came to control their pregnancy at the Ibarra health center and 37.5% were attended by the midwife, however, 15% of women among 45 years and 61 have schooling and they were never controlled in pregnancies, this factor mainly lies in the fact that the adopted figure of this population group on the doctor creates an image of insecurity unlike the midwife or healer of the community.

• A 40% of women aged 15-45 used contraception and women aged 46-61 in 29% reported that they did not use contraception. In the Angochagua parish, it was shown that women have access and information on contraceptive methods through health and education services, focusing on their fertility and the birth rate that it has declined in rural areas in recent years. The younger population group uses most of this knowledge through care in the sub center of Health.

References

- Depth demographic studies (2004) reproductive behavior of Ecuadorian women.

- Chevarria Lazo S (2008) Alternative development and native communities, ECLAC diagnosis. Santiago de Chile: UNFPA, UNCP.

- Rio FD, Alvis N, Yanez M, Acevedo RQK (2010) Woman, fertility and economy: Fifty years of research.

- Gomez LP (1999) Education and Fertility in Mexico and Colombia. Center for Demographic Studies.

- Guzman NA, Contreras MY, Perez RQ, Gonzalez KA, Carrasquilla FDR (2010) Fertility and participation of women in the labor market on the Caribbean coast and Colombia. Medwave.

- Unfpa, Inandep (1998) Study on indigenous women reproductive health and community organization Santiago de Chile. United Nations.

- Smock AC (1981) The education of women in developing countries: Opportunities and results New York: Praeger Publishers.

- Oppong C (1983) Roles of women, opportunity costs and fertility. In determinants of fertility in developing countries, supply and demand of children. New York: Academic Press 344-368.

- Cochrane SLD (1982) Parents of education and children's health: Evidence between countries, in the health and education policy. Washington.

Citation: Sara MRR, Viviana MEJ, María FVD, Maritza MAM, Steven JCR (2017) The Level of Education of Women Residing in the Parish of Angochagua-Ibarra and its Effect in the Sexual and Reproductive Health. J Community Med Health Educ 7:576. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000576

Copyright: © 2017 Sara MRR, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4619

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Nov 07, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3727

- PDF downloads: 892