The Influence of Parenting Styles and Parents' Perfectionism on Childrens' Sense of Entitlement in the City of Bandarabbas, Iran

Received: 15-Sep-2016 / Accepted Date: 17-Oct-2016 / Published Date: 21-Oct-2016 DOI: 10.4172/2375-4494.1000315

Abstract

This study examines the influence of parenting style and parents’ perfectionism on children’s sense of entitlement in the city of Bandarabbas, Iran. A total of 414 respondents, of whom 207 were parents and 207 were children, filled in the study's questionnaire, which had been designed to assess the primary variables of parenting style (authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive), parents’ perfectionism (self-oriented, other-oriented, and sociallyprescribed), and levels of children’s sense of entitlement. The results revealed that the parent-participants perceived their use of an authoritative parenting style as high and, in terms of their sense of perfectionism; they perceived themselves as high in both other-oriented perfectionism and socially-prescribed perfectionism. Also the childrenparticipants did not seem to possess a high sense of entitlement. The result of the hypothesis testing shows that the more the parent-participants subscribed to a sense of self-oriented perfectionism, the lower the sense of entitlement expressed by their children.

Keywords: Parenting style, Perfectionism, Children’s sense of entitlement, Personality test

218219Introduction

It is said that in today’s Iranian society, the level of demands children place on their parents has increased dramatically [1-5]. In addition, it is said by many parents and caregivers that the new generation is more demanding with a higher sense of entitlement compared to the previous generation [2,6]. When children today have high demands, it is often a desire for something expensive, and this can create a difficult situation for their parents. Such children will demand that they are given the object of their desire without any consideration for whether or not their demands are practical, and with no willingness to accept refusal. As the children become more single-minded in their demands, they develop a sense of psychological entitlement. The awareness of psychological entitlement has existed for at least several generations but there is a popular impression that it is something which has increased dramatically in society [7]. The psychological entitlement has mostly been studied in the context of western society; for instance, several researchers have made entitlement central to their thoughts regarding values and social justice [8].

Personality psychology includes both pathological and nonpathological approaches to understanding entitlement. From a clinical perspective, which focuses on the pathological concept of entitlement, entitlement is viewed as a component of a narcissistic personality [9]. In this context, entitlement is understood as an exploitive, unjustified demand for special treatment because of the person’s special capabilities, characteristics, and/or position. This type of entitlement is viewed as pathological and socially undesirable behaviour [10] that is related to revengefulness and includes difficulties with forgiveness [11], the expectation of success without personal responsibility [12], and problematic functioning in a work context [13]. Although entitlement is not always viewed as pathological, psychological entitlement continues to be conceptualized as an undesirable psychological state [7], or at least related to the constellation of negative personality traits defined as the Dark Triad of narcissism, psychopathic, and Machiavellianism [14]. This formulation of psychological entitlement involves characteristics of both entitlement and deservingness however, it continues to be conceptualized within a narcissistic context [15].

Limited research has been conducted into the levels of children’s sense of entitlement. However, Young and Klosko et al. [16] described sense of entitlement as a negative behavioural pattern that begins during the formative childhood years. They define children with a sense of entitlement as having no boundaries and limits with their parents and others, and always getting whatever they demand from their parents [16]. Such a child controls his or her parents and is never forced to take any responsibility in their house, such as doing household chores. They also do not know how to control their impulses or how to act out impulses, such as anger, without imposing sufficient negative consequences. These types of children typically exhibit a low level of tolerance for frustration, and the result of their unrealistic expectations is that they are liable to experience disappointment and hurt. To overcome this, they constantly nag and pester their parents who often relent in the face of their children’s persistent demands. These children view themselves as special and feel their needs are more important to them than the needs of others. They are demanding and controlling toward others, and they want to do things the way they want. They have difficulty accepting resistance when they want something. They want to make sure that they get what they want, how they want, and whenever they want. They get bored easily; routine tasks are just not for them, and they believe that they should not have to do them. They may break the rules, for example, by cheating in exams [16]. The negative results of this are that the children learn to continue their demanding behaviour. Experience teaches them that if you do not ask, you do not get, and if you keep asking, you are more likely to get what you want. They see that their parents often cave into their demands if they are persistent enough.

This present study aims to focus on parenting style and parent’s perfectionism and will measure the effectiveness of these two factors on the levels of children’s sense of entitlement.

Parenting style

Parenting styles play an important role in shaping child behavioural and psychological outcomes. Based on Baumrind’s theory [17], which is one of the most wel-known and comprehensive parenting theories, there are three types of parenting style: authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive [17]. According to this theory, authoritative parents use rational direction to manage their children’s activities in an “issueoriented manner” [17]. In contrast, authoritarian parents aim to “shape, control and evaluate” the way in which their children behave and act by using strict standards of conduct that may be theologically motivated (Baumrind, p.890 [17]). Permissive parents take a less controlling attitude of acceptance and affirmation of the children’s natural impulses, desires and behaviour [17]. Baumrind also explained that these three different parenting styles have varying impacts on children’s behaviour. For instance, many researchers have shown that Baumrind’s parenting styles influence children’s psychological development [18-21], children’s behaviours [17], behaviour problems [22], and children’s personality traits [19,23-25] More specifically, it is said that parents who are too submissive to their children’s demands have a negative influence on the level of their children’s expectations and demands, consequently leading the children to believe that they are the centre of the world [26]. Children raised in permissive, laissezfaire environments where they are spoiled and indulged never learned appropriate limits [16]. “Such children often grow up believing that they should get everything they want and they have the right to be angry if they do not get it. Children brought up with weak limits usually do not learn the notion of reciprocity. Their parents did not teach them that, in order to get something, they have to give something back. Rather, the message the parents give their children is that they would take care of them, and the children do not have to do anything in return [16]. This parenting style results in a ‘high demand’ child who has a sense of entitlement from others” [26]. According to Baumrind’s description of permissive parenting, it seems that parents with a permissive parenting style are more likely to have children with a sense of entitlement. Young and Klosko et al. [16] explained that parents’ behaviour towards their children’s main issue which can influence a sense of entitlement in their children; for instance, they argue that weak parental limits fail to exercise sufficient discipline and control over their children. Children are given whatever they want, whenever they want it. This may include fulfilling the children’s material desires or allowing them to have their own way. Parents of children with a sense of entitlement never teach their children frustration tolerance. They do not teach their children to take responsibility and complete assigned tasks. This may include chores around the house or schoolwork. Such parents allow the child to get away with irresponsibility by not following through with aversive consequences. These permissive parents never teach their children impulse control and allow children to act out impulses, such as anger, without imposing sufficient negative consequences.

It is important to mention that no research has been carried out to study the relationship between Baumrind’s three parenting styles and the levels of children’s sense of entitlement. However a study conducted by Segrin et al. [27] has shown that there is a clear connection between over-involved parenting and young adult children having a higher sense of entitlement. The belief is that when parents are overly protective, strive to maintain a positive affective state, and interfere too much instead of allowing their children to solve problems by themselves, this can lead to the child developing a false sense of deserving this treatment, not only from their parents, but also from others. Psychological entitlement is driven by this cognitive process [7]. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that persistent and continued over-parenting is a key factor contributing to a sense of entitlement in children.

Perfectionist parents

Perfectionism is considered a personality trait which is determined by specific characteristics, such as a drive to be perfect and a determination to achieve great and extreme criteria in performance with a tendency toward critical evaluation of behaviour [28,29]. As a personality trait, perfectionism should be recognized across different situations and life roles [30]. Following this reasoning, although it has been hypothesized that parents’ perfectionism has a significant role in shaping their children’s personalities, there is no solid empirical evidence supporting the relationship between parents’ perfectionism and children’s personality and behaviour; therefore, the present study seeks to contribute to the on-going research in this area.

According to Hewitt et al. [29], perfectionism has three dimensions: self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially-prescribed. Other-oriented perfectionism refers to the belief that it inessential for people to try hard in pursuit of perfection and to be perfect [28,31]. Individuals with other-oriented perfectionism expect other people to be perfect [28,29]. Other-oriented perfectionists are highly critical of other people who fail to meet these expectations [29]. On the other hand, self-oriented perfectionism refers to an internal belief that striving for perfection and being perfect is essential [28]. People with self-oriented perfectionism are highly self-critical, set high personal standards, and expect to be perfect [29]. Socially-prescribed perfectionism refers to perceived external beliefs that striving for perfection and being perfect are important to others [28]. Individuals with socially-prescribed perfectionism believe that other people expect them to be perfect, and if they fail to meet their expectations, others will be highly critical of them [31]. Also, studies have revealed two additional categories of perfectionism: negative (maladaptive) and positive (adaptive). Based on behavioural theory, Slade et al. [32] proposed a useful theoretical explanation of the key differences between positive (adaptive) and negative (maladaptive) perfectionism. According to their dual process model of perfectionism, overtly similar perfectionist behaviours (reflected in the tendency to set high performance standards) are associated with quite different cognitive processes and emotional states, depending on whether these behaviours appear in the function of achieving success (positive perfectionism) or avoiding failure (negative perfectionism).

Despite the attention that has been devoted to understanding adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism and their influence on different variables by Iranian researchers such as Besharat and his colleagues, no research has been conducted to study the influence of parents’ perfectionism on the levels of children’s sense of entitlement. It is said that, generally, there is a significant relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and the level of demands such that individuals with a higher level of maladaptive perfectionism have a higher level of demands [33-38]. As pointed out by Mitchelson et al. [39], parents with high levels of maladaptive perfectionism may impose unrealistically high expectations on their children, and consequently feel disappointed because their child is less than perfect. This is consistent with the study of Greblo et al. [40] who showed a negative relationship between mothers’ and fathers’ negative perfectionism and self-reported parental acceptance. On the other hand, it is shown that parents with higher levels of positive perfectionism not only accept their own individual limitations [41], but are also more prone to showing their children unconditional love and acceptance.

Method

Participants

The sample in this study consisted of 414 respondents, of whom 207 were parents comprised of 86% (n=178) female and 14% (n=29) male. In addition, of the 207 respondents who were children, 50% (n=103) were boys and 50% (n=104) were girls. The parents’ ages ranged from 25 years to 55 years, and the children’s ages ranged from 8 years to 11 years. In terms of the parents’ educational level, 9.0% (n=19) had completed postgraduate studies and above; 18% (n=37) had completed undergraduate studies; 46% (n=96) had completed high school; and 27% (n=55) had not completed high school and had no educational qualifications. In terms of the children’s educational levels, 10% (n=21) were in year two of primary school; 17% (n=36) were in year three of primary school; 24% (n=48) were in year four of primary school; and 49% (n=102) were in year five of primary school.

Procedure

The current research is a quantitative research study which is based on survey questionnaires. For the purposes of the study, two sets of questionnaire were prepared, one each for the parents and the children. To facilitate the gathering of data, the questionnaires were in the participants’ native Farsi language. In order to explain the nature and purpose of the questionnaire, cover letters were provided for both sets of participants. The sampling method used for this research is convenience sampling. The questionnaires were distributed in three primary schools in different demographic are as of the city of Bandarabbas. To gather the data from the parents, students were asked to take an envelope home to give to their parents. The envelopes contained a request for informed consent, questions on personal information, and two questionnaires: Parenting Style Questionnaire and Tehran Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (TMPS). In addition, a request for informed consent regarding their children’s questionnaire was included. Students who received informed consent from their parents were then asked to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of the following sections.

Ethical Consideration

Because the current study was carried out by independent practitioners, an assistant professor in counselling psychology was selected to review the submitted research proposal as an experienced independent chartered counselling psychologist. Strictly adhering to the code of human research ethic [42], the researchers also ensured that all data were handled in accordance with the code of ethic and conduct [43]. All participants in the study were given assurances regarding their anonymity and the confidentiality of their personal information. The participants were also provided with a chance to talk to the researchers about their shared professional capacity and were informed of their right to discontinue their participation in the study at any time if they so wished with no penalty or disadvantage to themselves. To ensure the participants’ confidentiality and anonymity, all identifying details were removed from the questionnaires.

Measures

Children’s questionnaire

Part 1: Personal information: A researcher-constructed set of questions was drafted in order to gather data on the demographic variables of age, gender, and ethnicity.

Part 2: Children’s sense of entitlement: Because no measure has been developed in previous studies to assess children’s sense of entitlement, items were developed specifically for this study. These items aimed to assess such phenomena as being demanding and controlling towards others, feeling special and more important than others, expecting everything should go their way, getting angry if they do not get what they want, getting bored easily, breaking the rules, and feeling that routine tasks are not for them. The items were based on descriptions of entitlement that appear in psychological literature [7,16] and other entitlement questionnaires, such as the Entitlement Rage subscale of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory Pincus et al. [44] the Narcissistic Personality Inventory [9], and the Psychological Entitlement Scale [7].

Response options were on a 5-point Likert scale (0=Never, 1=A little of the time, 2=Sometimes, 3=Most of the time, 4=Always). In order to investigate the factor structure of the children’s sense of entitlement scale, the children’s responses to the 11 entitlement items were subjected to a principal components analysis (PCA), followed by oblique rotation. An inspection of the main PCA results revealed that three factors have eigen-values of greater than 1.00. These three factors accounted for a combined total variance of 49.72%. Oblique rotation of these three factors failed to converge in 25 iterations, indicating that these three factors could not be separated as independent factors. Indeed, the component matrix shows that there is only one substantial factor in which 8 of the 11 items were loaded on to it. The other two factors consist of 3 items of which one is cross-loaded. The finding of a single substantial factor is supported by the Scree plot which shows essentially a single factor solution. The 8 items that load on Factor 1 clearly reflect the children-participants’ general sense of entitlement.Given the meaningfulness of this unitary factor, principal component analysis was once again conducted with the number of factors to be extracted limited to 1.

From the obtained component matrix, a total of 8 items were retained, using the criteria of selecting items with factor structure coefficients greater than or equal to 0.40 and no significant crosscorrelations. The use of the 0.40 value as a criterion for selecting items is based on the logic that squaring the correlation coefficient (0.40²) yields approximately 16% of the variance explained. An examination of these 8 items clearly shows that they reflect a general sense of entitlement by the study’s children-participants. Table 1 presents these 8 items together with their factor loadings.

| Children’s Sense of Entitlement scale | Factor loadings |

|---|---|

| I get very angry if I do not get what I want from my parents. (ce10) | 0.737 |

| School homework and house chores are not for me. (ce9) | 0.733 |

| I am entitled to break the rules. (ce11) | 0.729 |

| School rules are not for me. (ce5) | 0.651 |

| I am special and always better than other children. (ce8) | 0.52 |

| House rules are not for me. (ce2) | 0.497 |

| I am entitled to get everything and anything I want. (ce3) | 0.474 |

| I will never be happy until I get all that I want. (ce4) | 0.454 |

Table 1: The 8 items representing the children’s sense of entitlement together with their factor loadings.

Reliability analysis was conducted on the children’s sense of entitlement. The purpose of the reliability analysis was to maximize the internal consistency of the measure by identifying those items that are internally consistent (i.e., reliable), and to discard those items that are not. The criteria employed for retaining items are as follows: (1) any item with ‘Corrected Item-Total Correlation’ (I-T) >0.33 will be retained (0.33²) represents approximately 10% of the variance of the total scale accounted for), and (2) deletion of an item will not lower the scale’s Cronbach’s alpha. Table 2 presents the items for the scale with their I-T coefficients and Cronbach’s alphas.

As can be seen from the above Table 2, and based on the criteria for retaining items that are internally consistent, the factors of children’s sense of entitlement are represented by 8 items.

| Item-Total Statistics | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach's Alpha if Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|

| I get very angry if I do not get what I want from my parents. (ce10) | 0.606 | 0.697 |

| School homework and house chores are not for me. (ce9) | 0.568 | 0.706 |

| I am entitled to break the rules. (ce11) | 0.59 | 0.697 |

| School rules are not for me. (ce5) | 0.487 | 0.72 |

| I am special and always better than other children. (ce8) | 0.373 | 0.741 |

| House rules are not for me. (ce2) | 0.362 | 0.743 |

| I am entitled to get everything and anything I want. (ce3) | 0.337 | 0.748 |

| I will never be happy until I get all that I want. (ce4) | 0.306 | 0.756 |

| Cronbach’s alpha=0.753 | ||

Table 2: Scale items together with their corrected item-total correlations and Cronbach’s Alphas.

Parents’ questionnaire

Part 1: Personal information. A researcher-constructed set of questions was drafted to tap the demographic variables of age, gender, and ethnicity.

Part 2: Tehran Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (TMPS). The TMPS is a set of 30 items created by Besharat et al. [45] in the Farsi language based on the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) created by Hewitt et al. [29] and Besharat, et al. [45]. It is a self-report measure designed to assess several aspects of the construct of perfectionism, such as self-oriented perfectionism (1-3-5-7-9-11-13-14-15-21-23-25-26-28-30), other-oriented perfectionism (4-8-10-12-16-17-18-19-20-27-29), and socially prescribed perfectionism (2-6-22-24). The TMPS has excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, 0.91, and 0.81. The TMPS has been investigated regarding content, construct, and factorial validity. It nearly always achieves a validity coefficient of 0.79 or greater [46].

Part 3: Parenting Style Questionnaire. To assess parenting practices, Baumrind’s parenting style questionnaire was used. The questionnaire measures three parenting styles: permissive style (1-6-10-13-14-17-19-21-24-28), authoritarian style (2-3-7-9-12-16-18-25-26-29) and authoritative style (4-5-8-11-15-20-22-23-27-30). The questionnaire was translated into Farsiby Esfandiari in 1995 [46]. The questionnaire has an excellent reliability with alphas of.80 and greater for all three subscales: permissive style was 0.81, authoritarian style was 0.85, and authoritative style was 0.92. The Farsi version of the questionnaire has been tested and researched by Esfandiari and was found to show a fairly good reliability with alphas of 0.60 and greater: permissive style was0.69, authoritarian style was 0.77, and authoritative style was 0.73 [47].

Findings

What are the levels of the parent-participants’ parenting styles and sense of perfectionism and the children-participants’ sense of entitlement?

The following Table 3 presents the means and standard deviations for the seven computed factors.

| Mean | SD | Mid-Point | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permissive parenting style | 2.75 | 0.52 | 3 |

| Authoritarian parenting style | 2.56 | 0.61 | 3 |

| Authoritative parenting style | 4.21 | 0.46 | 3 |

| Self-oriented perfectionism | 2.81 | 0.46 | 3 |

| Other-oriented perfectionism | 3.36 | 0.61 | 3 |

| Socially prescribed perfectionism | 3.31 | 0.66 | 3 |

| Children’s sense of entitlement | 1.95 | 0.7 | 3 |

Table 3: Means and standard deviations for the computed factors of permissive parenting style, authoritarian parenting style, authoritative parenting style, self-oriented perfectionism, other-oriented perfectionism, socially prescribed perfectionism, and children’s sense of entitlement.

As can be seen from Table 3, the parent-participants rated their permissive and authoritarian parenting styles below their respective mid-points and rated their authoritative parenting style above the midpoint. Thus, the parent-participants perceived their use of an authoritative parenting style as high and their use of both permissive and authoritarian parenting styles as low. In terms of their sense of perfectionism, they rated their other-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism above their respective midpoints and rated their self-oriented perfectionism below the midpoint. Thus, in terms of their sense of perfectionism, they perceived themselves as high in both other-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism, and low in self-oriented perfectionism.

Table 3 also shows that the children-participants rated their sense of entitlement below its midpoint. Thus, these children-participants do not seem to possess a high sense of entitlement.

What is the impact of the parent-participants’ parenting styles and sense of perfectionism on their children’s sense of entitlement?

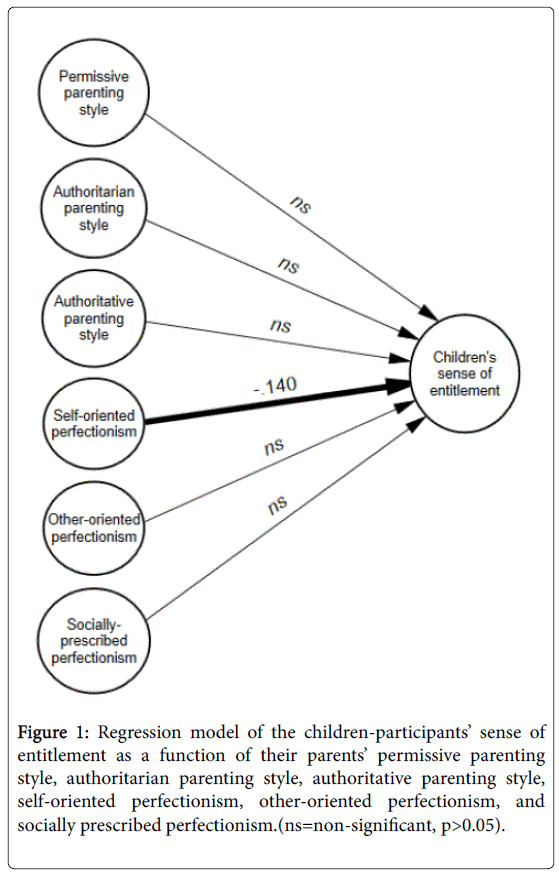

In order to test the impact of the parent-participants’ parenting styles (permissive, authoritarian, authoritative) and sense of perfectionism on their children’s sense of entitlement (represented by the regression model depicted in Figure 1), multiple regression analysis was conducted. The analysis involved regressing the factors of the children’s sense of entitlement on the predictor variables of permissive parenting style, authoritarian parenting style, authoritative parenting style, self-oriented perfectionism, other-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism. The results of the analysis are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Regression model of the children-participants’ sense of entitlement as a function of their parents’ permissive parenting style, authoritarian parenting style, authoritative parenting style, self-oriented perfectionism, other-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism.(ns=non-significant, p>0.05).

The results showed that of the six predictor variables generated from the parent-participants, only the variable of self-oriented perfectionism was found to be significantly and negatively associated with their children’ sense of entitlement. Thus, the higher the parent-participants subscribed to a sense of self-oriented perfectionism, the lower their children expressed a sense of entitlement (Beta=-0.14). The other five predictor variables were not found to be significantly related to the children-participants’ sense of entitlement.

Discussion

Many available articles in Iran have reported that the level of children’s sense of entitlement has increased and seems to be higher than in the previous generation [1-5]. However, these existing reports seem to be based on the reporters’ general observations alone and have not provided any scientific evidence to support their claims. Also neither of the existing reports explained the methodology or observations methods they employed. In addition, the results of this present study are in contrast to the reporters’ claims and show that the children-participants of the current study do not seem to possess a high sense of entitlement. Nevertheless, it should also be noted that the results of this study cannot be generalized in any shape or form.

Many available articles in Iran have reported that the level of children’s sense of entitlement has increased and seems to be higher than in the previous generation [1-5]. However, these existing reports seem to be based on the reporters’ general observations alone and have not provided any scientific evidence to support their claims. Also neither of the existing reports explained the methodology or observations methods they employed. In addition, the results of this present study are in contrast to the reporters’ claims and show that the children-participants of the current study do not seem to possess a high sense of entitlement. Nevertheless, it should also be noted that the results of this study cannot be generalized in any shape or form.

In addition, in this study, it was hypothesized that there is a relationship connecting the parenting style (permissive, authoritative and authoritarian) and the level of the parents’ perfectionism (selforiented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed oriented) with the level of the children’s sense of entitlement. Contrary to our expectations, the outcome of this study shows that only self-oriented perfectionism in the parent-participants has a negative predictive relationship with the children’s sense of entitlement such that the higher the parent-participants subscribed to a sense of self-oriented perfectionism, the lower their children expressed a sense of entitlement (Beta=-0.14). It is hard to explain and interpret these findings as there is no previous study to back them up. However, by understanding the characteristics of parents with self-oriented perfectionism and their influences on their children, we might be able to explain the children’s sense of entitlement in this study. As it was explained, self-oriented perfectionism refers to an internal belief that striving for perfection and being perfect is essential [28]. People with self-oriented perfectionism are highly self-critical, set high personal standards, and expect to be perfect [29]. For instance these parents may set high standards to pursue success in their life but end up worrying about mistakes after failing to achieve their standards and being criticized by others. The meaning of the success in the parents’ life can be anything. It can be related to their parenting style and their intention to raise perfect children, or it can be anything related to their personal life, education or work. Depression can be the result of self-oriented perfectionism in parents by causing the parents to focus on what will be lost rather than what will be gained [48]. Although there is no study that shows the influence of depression due to perfectionism in parents and the sense of entitlement in their children, there are some studies that show parents with depression have children with more aggressive behaviour and temper tantrums, and children with more internalizing problems, which seem to increase throughout young childhood [49].

In addition, it has not been determined in this current study whether the parents’ perfectionism is positive or negative. As previously explained, parents with higher levels of negative perfectionism more frequently report using harsh criticism in order to discipline (or punish) their children when they fail to meet parental expectations. Moreover, previous studies revealed that negative perfectionism is positively related to hostility, anger, and anger rumination [46]. However, it should be noted that, based on the results of this study, the parent-participants use of an authoritative parenting style is higher than other styles. Also, it can be interpreted that the authoritative parenting style possibly serves a buffer role to the negative influence of parents’ negative perfectionism which is in line with the low level of sense of entitlement among the childrenparticipants. It is understandable, therefore, that parents with authoritative parenting style are unlikely to have children with a sense of entitlement because they set boundaries for their children and encourage them to be independent [50]. Authoritative parents are not over-controlling parents. They discipline and control sufficiently while allowing their children to explore more freely, thus encouraging them to make their own decisions based upon their own reasoning. Authoritative parents give their children responsibility and produce children who are more independent and self-reliant [17]. Authoritative parents can understand how their children are feeling and teach them how to regulate their feelings [51] so their children learn how to control their impulses without excessive consequences.

The results of the present study also might be affected by its limitations. First of all, this research was conducted among a small and limited sample size; hence the results cannot be generalized in any shape or form. Secondly, as previously mentioned, as there is currently no standard test and measurement for the levels of children’s sense of entitlement, the researchers had to create a relevant test. The current test is age appropriate and was tested on a pilot group of 30 students in a primary school before being used in the actual test. In the pilot study, it had a high reliability of alpha 0.80, and in the actual test, the alpha was 0.85. However, as the study relied heavily on the results from the children’s sense of entitlement, which is a self-report tool, there is a possibility of invalid data. The children’s sense of entitlement questionnaire used a 5-point Likert scale, which could be confusing for this age group. Having a variety of response options may place confusing cognitive demands on the children as they are required to read all the available options and understand their differences. A higher number of options increases the likelihood of misunderstanding among the children. As the children in the current study were primary school level, their limited language development is likely to affect their comprehension and verbal memory. Therefore, the findings from the children’s expectations questionnaire should be treated with some caution as there is a possibility that the children did not fully understand the differences in the response options.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our study expanded current knowledge about the relationship between parenting style, parents’ perfectionism, and children’s sense of entitlement. Although the findings of the study reveal only one significant predictive relationship between selforiented perfectionism and children’s sense of entitlement, more research needs to be performed on the subject. It is recommended that future research use the exploratory research design to find the possible factors which can affect children’s expectations and demands. Also future research can focus on the effectiveness of various media on children’s sense of entitlement. In addition, while the present study employed a purely quantitative methodology to investigate the impact of the study's predictor variables on the levels of children’s sense of entitlement, future research could employ a mixed-design approach that incorporates both in-depth interviews and the survey/ questionnaire method that target both parents and children.

References

- Iran Newspaper (2010) Parents' bewilderment in children's negative competition. Iran Newspaper, 4559, 16.

- Ghajavand K (2014) What is the main reason of increasing a child's demands?

- Javadi MJ (2015) Modesty and hijab, the guarantor of the survival and health of the family and society.

- Musavi V (2015) Dismissing population control policies, is the best solution for the problem of divorce.

- Campbell KW, Bonacci AM, Shelton J, Exline JJ, Bushman BJ (2004) Psychological Entitlement: Interpersonal Consequences and Validation of a Self-Report Measure. J Pers Assessment 83: 29-45.

- Lerner MJ, Mikula G (1994) Entitlement and the affectional bond: Justice and close relationships. Springer, New York.

- Raskin R, Terry H (1988) A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. J Pers Social Psychol 54: 890-902.

- Bishop J, Lane RC (2002) The dynamics and dangers of entitlement. Psychoanal Psychol 19: 739-758.

- Exline JJ, Zell AL (2009) Empathy, self-affirmation, and forgiveness: The moderating roles of gender and entitlement. J Social Clin Psychol 28: 1071-1099.

- Chowning K, Campbell NJ (2009) Development and validation of a measure of academic entitlement: Individual differences in students' externalized responsibility and entitled expectations. J Educ Psychol 101: 982-997.

- Harvey P, Harris KJ (2010) Frustration-based outcomes of entitlement and the influence of supervisor communication. Human Relat 63: 1639-1660.

- Jonason PK, Luévano VX (2013) Walking the thin line between efficiency and accuracy: Validity and structure of the Dirty Dozen. Pers Individual Diff 55: 76-81.

- Żemojtel-Piotrowska MA, Piotrowski JP, Cieciuch J, Calogero RM, Van Hiel A, et al. (2015) Measurement of Psychological Entitlement in 28 Countries. European J Psychol Assess.

- Baumrind D (1966) Effects of Authoritative Parental Control on Child Behavior. Child Develop 37: 887-907.

- Schaefer RS (1965) Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Develop 36: 413-424.

- Gfroerer KP, Kern RM, Curlette WL, White J, Jonyniene J (2011) Parenting Style and Personality: Perceptions of Mothers, Fathers, and Adolescents. J Individual Psychol 67: 57-73.

- Mahmoodi M (2014) Family function, Parenting Style and Broader Autism Phenotype as Predicting Factors of Psychological Adjustment in Typically Developing Siblings of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Iran J Psychiat 9: 55-63.

- Williams KE, Ciarrochi J, Heaven PL (2012) Inflexible Parents, Inflexible Kids: A 6-Year Longitudinal Study of Parenting Style and the Development of Psychological Flexibility in Adolescents. J Youth Adolescence 41: 1053-1066.

- Alizadeh S, Abu Talib MB, Abdullah R, Mansor M (2011) Relationship between parenting style and children’s behavior problem. Asian Social Sci 7: 195-200.

- Kitamura T, Shikai N, Uji M, Hiramura H, Tanaka N, et al. (2009) Intergenerational Transmission of Parenting Style and Personality: Direct Influence or Mediation? J child Family Stud 18: 541-556.

- Datu JA (2012) Personality traits and paternal parenting style as predictive factors of career choice. Acad Res Int 3: 118-124.

- Uji M, Sakamoto A, Adachi K, Kitamura T (2014) The impact of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting styles on children’s later mental health in Japan: focusing on parent and child gender. J Child Family Stud 23: 293-302.

- Veeraraghavan V (2006) Behaviour Problems in Children & Adolescents (A guide to Parents, Teachers and Mental Health Profesionals. Northern Book Centre, New Delhi.

- Segrin C, Woszidlo A, Givertz M, Bauer A, Murphy MT (2012) The Association Between overparenting, Parent-Child Communication, and Entitelment and Adaptive Traits in Adult Children. Family Relat 61: 237-252.

- Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R (1990) The dimensions of perfectionism. Cogn Ther Res 14: 449-468.

- Hewitt PL, Flett GL (1990) Perfectionism and depression: A multidimensional analysis. J Social Behav Pers 5: 423-438.

- Flett GL, Hewitt PL, Oliver JM, Macdonald S (2002) Perfectionism in children and their parents: A developmental analysis. In: Flett GL, Hewitt PL, Perfectionism. American Psychological Association, Wasington, DC.

- Flett GL, Hewitt PL, Blankstein KR, Mosher SW (1991) Perfectionism, self-actualization, and personal adjustment. J Social Behav Pers 6: 147-160.

- Slade PD, Owens RG (1998) A dual process model of perfectionism based on reinforcement theory. Behav Modification 22: 327-390.

- Brown EJ (1999) Relationship of perfectionism to affect, expectations, attributions and performance in the classroom. J Social Clin Psychol 18: 98-112.

- Kopalle PK, Lehmann DR (2001) Strategic management of expectations: The role of disconfirmation sensitivity and perfectionism. J Market Res 38: 386-394.

- Stairs AM, Smith TG, Zapolski TB, Combs JL, Settles RE (2012) Clarifying the Construct of Perfectionism. Assess 19: 146-166.

- Kim LE, Chen L, MacCann C, Karlov L, Kleitman S (2015) Evidence for three factors of perfectionism: Perfectionistic Strivings, Order, and Perfectionistic Concerns. Pers Individual Diff 84: 16-22.

- Nealis LJ, Sherry SB, Sherry DL, Stewart SH, Macneil MA (2015) Toward a better understanding of narcissistic perfectionism: Evidence of factorial validity, incremental validity, and mediating mechanisms. J Res Pers 57: 11-25.

- Stoeber J, Sherry SB, Nealis LJ (2015) Multidimensional perfectionism and narcissism: Grandiose or vulnerable? Pers Individual Diff 80: 85-90.

- Mitchelson JK, Burns LR (1998) Career mothers and perfectionism: Stress at work and at home. Pers Individual Diff 477-485.

- Greblo Z, Bratko D (2014) Parents’ perfectionism and its relation to child rearing behaviours. Scandinavian J Psychol 55: 180-185.

- Enns MW, Cox BJ (2002) The nature and assessment of perfectionism: A critical analysis. In: Flett GL, Hewitt PL, Perfectionism: Theory, research and practice (pp. XX-XX). American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

- BPS (2009) Code of Ethics and Conduct, Guidance published by the Ethics Committee of the British Psychological Society.

- Pincus LA, Ansell BE, Pimentel CA, Cain NM, Wright AG, et al. (2009) Initial Construction and Validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. American Psychological Association 21: 365-379.

- Besharat MA (2007) Reliability and validity of Tehran Multidimentional Perfectionism Scale (TMPS). Psychol Res 10: 49-67.

- Besharat MA, Azizi K, Hoseyni A (2010) Relationship between parents' perfectionism and parenting style. Res educ sys 8: 10-30.

- Ahmadi V, Ahmadi S, Dadfar R, Nasrolahi A, Abedini S, et al. (2014) The relationships between parenting styles and addiction potentiality among students. J Paramed Sci 5: 2-6.

- Kobori O, Tanno Y (2005) Self-Oriented Perfectionism and its Relationship to Positive and Negative Affect: The Mediation of Positive and Negative Perfectionism Cognitions. Cogn Ther Res 29: 555-567.

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2003) The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. J Abnormal Psychol 112: 179-192.

- Santrock JW (2007) A Topical Approach to Life-span Development, 3rd Edn. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Berger S (2011) The Developing Person Through the Life Span. Worth Publisher, New York.

Citation: Yadegarfard M, Yadegarfard N (2016) The Influence of Parenting Styles and Parents’ Perfectionism on Childrens’ Sense of Entitlement in the City of Bandarabbas, Iran. J Child Adolesc Behav 4:315. DOI: 10.4172/2375-4494.1000315

Copyright: © Yadegarfard M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16314

- [From(publication date): 10-2016 - Nov 22, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 15418

- PDF downloads: 896