Review Article Open Access

The Importance of Palliative Care for Terminally Ill Cancer Patients and their Family Members

Gerd I. Ringdal1* and Beate André21Gerd Inger Ringdal, PhD, Professor, Department of Psychology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, No-67491 Trondheim, Norway

2Beate André, RN, PhD, Associate Professor, Faculty of Nursing, Sør-Trøndelag University College, Trondheim, Norway, Research Centre for Health Promotion and Resources, The Sør-Trøndelag University College (HiST) and Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway

- *Corresponding Author:

- Gerd Inger Ringdal, PhD

Professor, Department of Psychology

Norwegian University of Science and Technology

NTNU, No-67491 Trondheim, Norway

Tel: 4773591960

Fax: 4773591920

Email: gerd.inger.ringdal@svt.ntnu.no

Received date: March 28, 2014; Accepted date: April 17, 2014; Published date: April 28, 2014

Citation: Ringdal GI, André B (2014) The Importance of Palliative Care for Terminally Ill Cancer Patients and their Family Members. J Palliat Care Med 4:176. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000176

Copyright: © 2014 Ringdal GI, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

The present paper focuses on close family members’ report of satisfaction with the care that terminally ill cancer patients and their close family members receive at the end of the patients’ life. The situation today is that the death has moved out of the home and into the institution. It seems that the more developed a country's health care system is, the fewer patients die at home.

Key words

Palliative care; Terminally ill cancer patients; Family members

The Aim of Palliative Care

Palliative care is active, holistic care and treatment for patients with incurable diseases and short expected time left to live [1-3]. Relieving physical pain and other bothersome symptoms are central together with efforts against psychological, social, spiritual and existential problems. The aim of palliative care is to improve both the patients’ and the close family members’ quality of life and well-being.

Do health care personnel have the courage and take the time it needs to listen to the terminally ill who often have thoughts and wishes in their last days to live? Talking about the death may create safety and reduce anxiety for all the involved. Unpleasant symptoms occur frequently among dying patients in hospitals the last days of their lives. In order to provide dignity for the terminally ill’s last days and the death, improving relief of symptoms of physical, psychological, spiritual and existential character is needed. It may be challenging for the health care personnel to open up for talks with palliative patients about short expected time left to live and about the death. Dignity in death is related to having someone together with them in the death moment. It is important that the dying one receive good pain relief and support to cope with anxiety, worries, and physical symptoms. To succeed in this, cooperation among the patients, close family members and health personnel is provided [4].

Although dying patients may have different needs and wants, there are some assumptions that characterize "good care” for the dying, such as relief from emotional and physical problems, social support, continuity in care, and good communication both with the physicians and the nurses [5-10]. To evaluate palliative care, satisfaction with care is an often used method [11,12].

In the last decades several kinds of palliative care have been developed, such as home care and hospice. So far few randomized trials comparing such program with traditional treatment have been executed. Based on existing studies it is difficult to make any certain conclusions about what kind of influences such interventions may have on the patients’ and the close family members’ satisfaction with the palliative care they receive [13].

Palliative Care and Treatment Compared with Traditional Treatment

In order to evaluate the importance of palliative care and treatment compared with traditional treatment, a cluster randomized study was performed at the Palliative Medicine Unit (PMU), at the University of Trondheim in Norway, where the results are published in several articles [13-18]. The present article is mainly based on original research published in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management [15] and in Quality of Life Research [16]. In order to measure satisfaction with palliative care and to follow up the care that the patients and their families received, it was used a scale including 20 items, the FAMCARE (Family Satisfaction with Care) Scale [12].

The PMU program comprises a holistic and multi-disciplinary approach including both physical, psychological, social and existential aspects of the treatment, where the patients’ as well as the families’ situations and needs are important to take care of to ensure their integrity. On this background we examined whether family members of patients at the PMU (i.e. the intervention group) would report to be more satisfied with the care and treatment than family members of patients receiving traditional treatment in ordinary cancer units.

Family Members’ Reports of Satisfaction with Care

The data was based on answered questionnaires from 183 family members, where two out of three were spouses, or partners, and one-third were children of the terminally ill cancer patients with a predicted survival time of two to nine months. Of these 113 were family members of patients at the Palliative Medicine Unit (PMU) (intervention group), while the other 70 were family members of patients at traditional cancer units (control group).The age of the family members was from 27 to 81 years (median 58 year). The data was collected about one month after the death of the cancer victims.

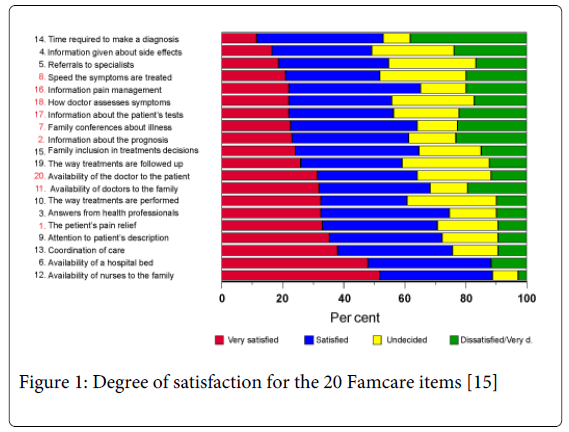

The results displayed in Figure 1 show that 60% and 90% of the family member in the total sample reported that they were ‘very satisfied’ or ‘satisfied’ with the treatment and care [15]. The items marked with red show significant differences between family members of patients in the intervention group (at the PMU) and in the control group. Family members of patients in the intervention group reported to be most satisfied with the care. Satisfaction with pain and symptom relief (items 1 and 18), information about how to manage the pain (item 16), information about the patient’ tests and prognosis (items 2 and 17) were significant higher among the family members of patients in the intervention group than the family members to patients in the control group. The family members of patients in the intervention group reported significant higher satisfaction with family conversations with physicians and nurses discussing the patients’ disease and treatment (item 7) and the physicians’ availability for the family and the patient (item 11). Furthermore, family members of male patients reported to be more satisfied with treatment and care than family members of female patients. Place of death was also important [15]. The family members of patients who died at home reported to be more satisfied with the treatment and the care compared to the family members of those who died at hospitals or nursing homes.

Discussion

Generally high levels of satisfaction with the palliative care were reported among the family members of patients in the intervention group as well as the family members of patients in the control group [15]. The high amount of those who reported satisfaction with care is in accordance with earlier findings [6,7,12]. It has been discussed as a method problem in assessment of satisfaction also named ‘ceiling effect’ indicating poor ability to discriminate between groups of respondents [19,20]. There may be different reasons, for instance, it may be that the patients hesitate in giving negative evaluation of the treatment and care at the hospital where they themselves are patient, and it may be that the instrument used is not sensitive enough to discover changes of satisfaction over time. Another reason may be that such studies often use a retrospective design, which also was the case in our study [15], where it is not possible to exclude the problem that remembering increase with time. Based on this possible methodological shortcoming, it has been claimed that satisfaction research is of little importance. We found, however, a significant difference between the respondents who were family members of patients participating in the intervention group and the family members of the patients in the control group [15]. The family members of those in the first mentioned group reported significantly higher satisfaction with care than those in the control group, particularly in terms of information about prognoses and treatment, availability of physicians both for patients and families, and pain relief and treatment of symptoms.

There is no doubt that the focus on the total situation of the patient is important for how satisfied close family members are with the palliative treatment and care. Such a holistic focus might discover problems and challenges that the patients and family members experience at an early stage and help them to find solutions [4,21]. Since information and communication, as well as attention seem to be important in the palliative cancer treatment [15] and since the intervention program showed that it is possible for more patients to die at home [14], this gives us good arguments to continue and further develop the palliative care that are given at hospices and to continue the research that may improve the palliative care.

References

- Faber-Langendoen K, Lanken PN (2000) Dying patients in the intensive care unit: forgoing treatment, maintaining care. Ann Intern Med 133: 886-893.

- [No authors listed] (1990) Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 804: 1-75.

- WHO (2008-13). Palliative Care. Action plan for the global strategy for prevention and control for noncommunicable diseases.

- André B (2010) Change can be challenging - Introduction to changes and implementation of computerized technology in health care. Trondheim: NTNU. Doctor Dissertation.

- Richardson J (2002) Health promotion in palliative care: the patients' perception of therapeutic interaction with the palliative nurse in the primary care setting. J Adv Nurs 40: 432-440.

- Fakhoury W, McCarthy M, Addington-Hall J (1996) Determinants of informal caregivers' satisfaction with services for dying cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 42: 721-731.

- Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, Hood K, Edwards AG, et al. (2003) Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? J Pain Symptom Manage 25: 150-168.

- Rinck GC, van den Bos GAM, de Haes HJCJM, et al. (1997). Methodological issues in effectiveness research on palliative cancer care: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 15: 1697-1707.

- Ringdal G, Ringdal K, Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S (2007) Does social support from family and friends work as a buffer against reactions to stressful life events such as terminal cancer? Palliat Support Care 5: 61-69.

- Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, et al. (2000) Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 284: 2476-2482.

- Hearn J, Higginson IJ (1998) Do specialist palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic literature review. Palliat Med 12: 317-332.

- Kristjanson LJ (1993) Validity and reliability testing of the FAMCARE Scale: measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med 36: 693-701.

- Jordhøy MS, Fayers P, Loge JH, Ahlner-Elmquist M, Kaasa S (2001). Quality of life in palliative cancer care: Results from a cluster randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 19; 18: 3884-3894.

- Jordhøy MS, Fayers P, Saltnes T, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Jannert M, et al. (2000) A palliative-care intervention and death at home: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 356: 888-893.

- Ringdal GI, Jordhøy MS, Kaasa S (2002) Family satisfaction with end-of-life care for cancer patients in a cluster randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 24: 53-63.

- Ringdal GI, Jordhøy MS, Kaasa S (2003) Measuring quality of palliative care: psychometric properties of the FAMCARE Scale. Qual Life Res 12: 167-176.

- Ringdal GI, Jordhøy MS, Ringdal K, Kaasa S (2001) Factors affecting grief reactions in close family members to individuals who have died of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 22: 1016-1026.

- Ringdal GI, Jordhøy MS, Ringdal K, Kaasa S (2001) The first year of grief and bereavement in close family members to individuals who have died of cancer. Pall Med 15: 91-105.

- Wilkinson EK, Salisbury C, Bosanquet N, Franks PJ, Kite S, et al. (1999) Patient and carer preference for, and satisfaction with, specialist models of palliative care: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med 13: 197-216.

- Asadi-Lari M, Tamburini M, Gray D (2004) Patients' needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: towards a comprehensive model. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2: 32.

- André B, Sjøvold E, Rannestad T, Holmemo M, Ringdal GI (2013) Work Culture among Healthcare personnel in a Palliative Medicine Unit. Palliat Support Care 11: 135-140.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 18988

- [From(publication date):

April-2014 - Apr 03, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 14254

- PDF downloads : 4734