The Impact of Variant Local Involvement in Community Based Ecotourism: A Conceptual Framework Approach

Received: 22-Apr-2019 / Accepted Date: 13-May-2019 / Published Date: 20-May-2019

Abstract

This study was conducted to determine the impact of variant local involvement in ecotourism and associated strengths and weaknesses of the Adaba-Dodola community based ecotourism project, in South Ethiopia. Households from CBECT program and non-program communities, focus groups of CBECT participants and nonparticipants, and key-informants from culture and tourism office and from Oromia forest and wildlife enterprise were the target respondents. The primary data were collected through questionnaires, interviews and focused group discussions. Document reviews were also made to support the study. The quantitative data were analyzed through descriptive statistics while the qualitative data were analyzed in the form of narrations. The result of the study indicated that participants were highly benefited compared to nonparticipants due to the different level of participation and ways of involvement in ecotourism activities. Participants were benefited economically while nonparticipants enjoyed benefits associated with natural services. This led to positive perception to exist in participants than nonparticipants. As a result, the perception of communities towards ecotourism had been impacted by the difference of ecotourism support in the livelihood of participant and nonparticipant communities. In relation to this, working with community and promoting experience sharing for communities were the main strengths of ecotourism program according to participants while majority of nonparticipants stated as there were no major strengths to the ecotourism project. Subsequently, both groups identified insufficient implementation of the CBECT program as the main weakness of ecotourism in the area.

Keywords: Community-based ecotourism; Conceptual framework; Impact; Local involvement

Introduction

Community-based ecotourism (CBET) is a form of tourism which promotes the local community involvement, management and local control over the tourist destinations [1,2]. Ecotourism enhances the conservation of nature, culture, local economic benefit and enjoyment of natural beauty for tourists [3]. As ecotourism is the main source of income and employment for communities in tourism destinations, the development and increase of tourist flow to these areas offers a great livelihood opportunity to the local communities [4].

Ecotourism has caught the interest of many people and communities in the developing countries due to its different values. It reduces economic leakages and undesirable environmental impacts, and stimulates the development of rural destinations [5]. In addition, ecotourism enhances societal development through sharing ideas with tourists on how to improve their community, learning new information from tourists and establishing long-lasting friendships [6]. As a result, ecotourism is crucial to sustain the environment, society and the economy [2].

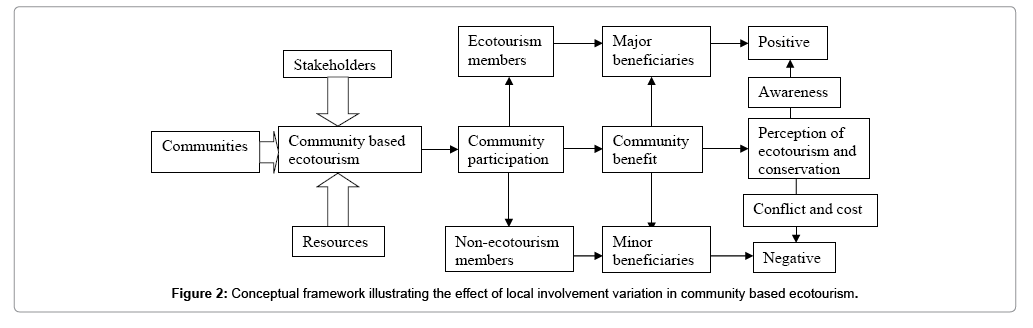

Community-based ecotourism is created by linking ecotourism to community-based development [7]. If community based ecotourism initiatives are effectively implemented, they support the local communities in different aspects such as enhancing better linkages, creating local employments, creating multiplier effect, and promoting conservation of biodiversity [8,9]. Similarly, it enhances the involvement of local community in the development and management of the touristic sites in a significant manner [7]. However, communitybased ecotourism can also bring economic inequalities within the community. According to Sundufu et al. [10], the eco-tourism industry created distributional inequalities locally. The variation in participation of communities in community based ecotourism affects the awareness and perception of communities [11]. The supposition that a distinctive, neutral and homogeneous community exists is one of the central operational problem of CBET [12].

The Adaba-Dodola community based ecotourism is one of the ecotourism initiatives in Ethiopia which has been established in 1995. It involved different kebeles in which both male and female households take a part in various ecotourism activities that helps them to obtain economic benefits. In contrast, there are also local communities that have not involved in the ecotourism program, and there is variation of participation in the community-based ecotourism initiative in the area [13]. But, the types of benefits enjoyed between CBECT participants and nonparticipants from the ecotourism initiative were not adequately addressed in the area. Moreover, studies lack on the effects of ecotourism benefits between participants and nonparticipants, and strengths and weaknesses of the community based ecotourism program in the area. Hence, the overall perspective of this study is to determine the effect of local involvement variation in Adaba-Dodola community based ecotourism and associated strengths and weaknesses in Adaba- Dodola districts, in South Ethiopia.

Methodology

Description of the study area

The study was carried out in Adaba and Dodola Woredas (districts). The Woreda is the second lowest administrative unit of the current Ethiopia with several kebeles (composition of villages) on its area. Both districts were selected because they are places where the Adaba-Dodola community based ecotourism project is found. They are in South Eastern part of Ethiopia, found in Oromia regional state, West Arsi Zone (Figure 1). The 2007 National census report indicated that the total population of the Adaba district was 138,717, while the total population of the Dodola district was 193,812 [14]. The agroclimate zone of the study area ranges from Dega to Wurch which are characteristics of most of the Ethiopian highlands. The rainfall distribution is bimodal having two rainy seasons per year. The mean annual rainfall is 912.5 mm and the mean annual temperature is 15.6°C [15].

Adaba-Dodola community based ecotourism project

Adaba-Dodola community based ecotourism project was established based on the forest priority area of Adaba-Dodola which is one of priority forest areas of the country. This project was initiated to control the unregulated access to the natural forests since all attempts to regulate access have failed in the past [16]. The Adaba Dodola forest priority area is located 345 km far from Addis Ababa with an attitude between 2400 and 3753 m above sea level. It is found on the escarpment that start from Adaba to Bale mountain and extends between 6° 50’-7° 0’ North Latitude and 39° 07’-39° 22’ East Longitude on the Southern plateaus [15].

Sampling design

For this specific study, our target groups were the two Adaba and Dodola districts, culture and tourism offices, Oromia forest and wildlife enterprise and local communities. Stratified random sampling technique was employed to select the sample households from the participant and nonparticipant groups. Adaba and Dodola districts comprise 35 kebeles in which 18 are in Adaba while 17 are in Dodola. From these, 6 kebeles are currently involved or they are direct participants in community based ecotourism activities using legal system whereas 29 kebeles are not involved or nonparticipants of the community based ecotourism activities. From the 6 kebeles, 5 in Dodola and 1 in Adaba are currently involved in the ecotourism development activity. From these 6 kebeles (4 from Dodola and 1 from Adaba) from the two districts were selected purposely based on coverage of forest area, time of establishment and total number of households involved to obtain adequate data on community based ecotourism of the area. For comparing the effect of participation in ecotourism between participant and nonparticipant groups, 5 kebeles from the 29 kebeles of nonparticipant groups were randomly selected.

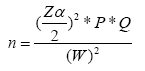

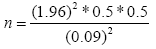

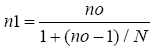

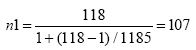

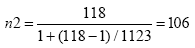

However, the total sample size of households was determined based on Cocheran formula [17]. The total number of households found in target sample kebeles both in participant and nonparticipant kebeles were 2308, of which Bura Adele, Denba, Keta Berenda, Ashena Robe and Bucha are from participant kebeles with 556, 150, 269, 120 and 90 households, respectively. Whereas, Barisa, Kechema, Hara Ganata, Ejersa Chumogo and Wesha were the nonparticipant kebeles with 158, 248, 269, 149 and 299 households, respectively [13]. The sample size for the participant and nonparticipant kebeles was determined based on the following equation:

(1)

(1)

where,  at α=95% confidence interval, P × Q is estimate of marginal variance in which it is 5% and W=Researchers willingness to accept margin of error in which we take 9%

at α=95% confidence interval, P × Q is estimate of marginal variance in which it is 5% and W=Researchers willingness to accept margin of error in which we take 9%

(2)

(2)

n=118 participant and non-participant kebeles

If the value of n is greater than 5% of the population we can apply the Cocheran correction formula [17] which is given by

no=118

Therefore, the sample size for participant groups was:

(3)

(3)

The sample size for the non-participant kebeles was:

(4)

(4)

Sample household heads were selected proportionally both from participant and nonparticipant kebeles. Accordingly, the sample household heads for the participant kebeles, Bura Adele, Deneba, Keta Berenda, Ashena Robe and Bucha were 50, 14, 24, 10 and 9, respectively. While the sample household heads for the nonparticipant kebeles, Berisa, Kechema, Hara Genetaa, Ejersa Chumogo and Weshaa were 15, 24, 25, 14 and 28, respectively.

Method of data collection

The data collection activity of this research was conducted starting from November 2014 to June 2015. Data were gathered using interviews, questionnaire survey and focused group discussions. Secondary data were also obtained from Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise Offices of Adaba-Dodola branch. Interview both with participants and nonparticipants of the program was made to gather adequate data about the ecotourism benefits in the area. Interview was also made with key informants to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the community based ecotourism program in the area.

Questionnaire distribution was made to collect data on types and extent of ecotourism benefits among participants and nonparticipants, and to assess the strengths and weaknesses of community based ecotourism. To achieve this, semi-structured questionnaire was prepared and administered for selected sample households from participant and nonparticipant groups in both Adaba and Dodola districts. During the questionnaire survey, provision of extra questionnaires was undertaken to fill the gap of no responses by the sample households.

Finally, the data collection process was supported with focus group discussion from both participant and nonparticipant groups and secondary sources from relevant offices. Two focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted on each target groups (Four FGDs for the whole study). In each FGD, one community leader, four elders of villages, one officer from the community based ecotourism program, one expert from wildlife and forest enterprise of the districts, one expert from culture and tourism office of each district, government administrators and one from female association were selected and discussed on strengths, weaknesses and related historical perspectives of community based ecotourism in both districts. FGD was taken place for two months (two days in a week). In addition, documents (on members of the community based ecotourism program) from Oromia forest and wildlife enterprise offices of Adaba-Dodola branch were included to substantiate the study.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistical methods such as percentages were used to analyze the extent and types of ecotourism benefits for participants and nonparticipants, and strengths and weaknesses of community based ecotourism in the area. Chi-Square tests of SPSS Version 20.0 Software were used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics. Statistical tests used were two-tailed with 95% confidence intervals. The responses on weaknesses and strength of community based ecotourism by key informants and focus group discussions (with members of participant and nonparticipant groups) were analyzed in the form of narration. Moreover, conceptual framework has been developed to represent the effect of local involvement variations in community based ecotourism.

Results and Discussion

Description of the socio-demographic characteristics of sample households

From the 107 respondents who were selected from participant communities in Adaba and Dodola districts, about 81 (75.7%) were males whereas 26 (24.3%) were females. The number of males was significantly higher than females (χ2=28.271, df=1, p=0.00). Significant variation was also observed in the age category, educational level and in the occupation type of the participant respondents. Of the selected 106 respondents from nonparticipant groups, 84 (79.25%) were males while 22 (20.75%) were females. There was significant difference between males and females (χ2=36.264, df=1, p=0.00). Significant variation was also observed in the age category and occupation of the respondents while no significant variation was observed in the educational level of nonparticipant groups (Table 1).

| Respondents | Variables | Categories | N | % | χ2 | df | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Sex | Male | 81 | 75.70 | 28.271 | 1 | 0.00 |

| Female | 26 | 24.30 | |||||

| Age | 18-32 | 8 | 7.48 | 43.981 | 2 | 0.00 | |

| 33-44 | 35 | 32.71 | |||||

| ≥45 | 64 | 59.81 | |||||

| Education | Literate | 13 | 12.15 | 61.318 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| Illiterate | 94 | 87.85 | |||||

| Occupation | Employee | 1 | 0.93 | 185.000 | 3 | 0.00 | |

| Merchants | 4 | 3.74 | |||||

| Farmer | 87 | 81.31 | |||||

| Others | 15 | 14.02 | |||||

| Sex | Male | 84 | 79.25 | 36.264 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| Female | 22 | 20.75 | |||||

| Age | 18-32 | 21 | 19.81 | 8.849 | 2 | 0.012 | |

| 32-44 | 41 | 38.68 | |||||

| Nonparticipants | ≥45 | 44 | 41.51 | ||||

| Education | Literate | 56 | 52.83 | 0.340 | 1 | 0.560 | |

| Illiterate | 50 | 47.17 | |||||

| Occupation | Employee | 1 | 0.94 | 192.642 | 3 | 0.00 | |

| Merchants | 12 | 11.32 | |||||

| Farmer | 88 | 83.02 | |||||

| Others | 5 | 4.72 |

N: Number of respondents; %: Percentage

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the sample households.

As it has been observed in the above table, the majority of respondents from CBECT participants and nonparticipants were males. Females were not actively involved in the community based ecotourism activities in the area. Concerning the age of respondents, the majority of participants and nonparticipants were characterized by the age of above 45 years. This indicates the younger groups have limited involvement in the CBECT initiative. This might be due to the ecotourism project of the area basis on households for its implementation. In the study area, the major groups of respondents from participants are illiterate while the major groups of respondents from nonparticipants are literate. Education is one of the variables in which more difference had been observed between participant and nonparticipant communities. In addition, farming is the main livelihood of both CBECT participant and nonparticipant communities. Community based ecotourism of the area was designed to improve this livelihood of communities and promote forest and natural resource conservation in the areas [16].

The importance of Adaba-Dodola community based ecotourism for local people

Economic benefits of ecotourism for participants and nonparticipants in the area: The economic benefits of ecotourism for participants and nonparticipants are given in Table 2. All participants revealed as they obtain economic benefits while the majority of nonparticipants indicated as they do not benefit from ecotourism. In the study area, community based ecotourism provides alternative job opportunities for communities to improve their life. However, the level of participation and ways of involvement in ecotourism activities varies between participants and nonparticipants of the ecotourism program. Nonparticipants are excluded from direct participation in ecotourism activities as well as benefits obtained as a member of unions because of the inadequate implementation of the CBECT program. In our study site, participation to ecotourism involves direct economic benefits, trainings and awareness creation and ownership of the resources. This has led to negative perception of nonparticipants. Nonparticipants involve in a certain ecotourism activities not requiring membership. That is why, the majority of nonparticipant respondents described as they do not benefit from ecotourism. According to Sundufu [10], the presence of distributional inequalities among residents within the eco-tourism industry locally creates complaints about ecotourism and its benefits. Similarly, the decline of tourism-related jobs and income leads people to negatively feel about ecotourism and its role. This indicates the need to attach individuals with ecotourism in terms of employment, household income, etc. This enables to ensure the expectations of communities are met and reduce large-scale disappointment on the part of communities [18].

| Economic benefits | P | NP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Yes | 107 | 100.00 | 35 | 33.02 |

| No | 0 | 0.00 | 71 | 66.98 |

P: Participants; NP: Nonparticipants; N: Number of respondents; %: Percentage

Table 2: Economic benefits of ecotourism for local communities.

In contrast, participants are the main actors and beneficiaries of ecotourism program compared to nonparticipants in the study area. The interview with participants indicated as they obtain benefits from different ecotourism services they provide. The interview with Kemal, The Chairman of the enterprise based farmers union described the ecotourism benefit for participants. He said that participants obtain economic benefit by involving in ecotourism union. They benefit from ecotourism activities like tourist hunting services, fees of tour guide services and horse rental activities of members. Participant respondents in Ashena Robe PAs, South of Dodola Woreda and adjacent to Nensebo districts of West Arsi zone revealed the indirect economic benefits of the dense forest of ecotourism as a foraging place for their small ruminants livestock like sheep and goat in large scale. In the area, members from participant group around the districts were observed participating in various ecotourism activities. As a result they had positive perception towards ecotourism in terms of economic benefit and promoting conservation. This is similar to the study of Sundufu [10], in which those respondents who economically benefited from eco-tourism were more positive about it than those without such benefits. Similarly, the study by Snyman [11], shown as direct benefits obtained by ecotourism participants through salaries, wages and training offer tangible and measurable impacts directly related to conservation. CBET in the area is interpreted as bringing economic inequalities and disparities in economic benefits between participant and nonparticipant community. Here, we can therefore conclude that CBET brings both economic empowerment and disempowerment at the same time in which participants are economically empowered while nonparticipants are economically disempowered [12].

Ways of community benefits from community based ecotourism in the districts: The main ways of ecotourism benefits for community in the area include economic benefit for participants and natural benefits for nonparticipants. The benefits illustrated by participants and nonparticipants are given in Table 3.

| Ecotourism benefits | Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | NP | |||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Economic | 76 | 71.03 | 28 | 26.41 |

| Social | 10 | 9.34 | 7 | 6.60 |

| Natural and ecosystem values | 13 | 12.15 | 69 | 65.10 |

| Capacity building | 8 | 7.48 | 2 | 1.89 |

P: Participants; NP: Nonparticipants; N: Number of respondents; %: Percentage

Table 3: Various ways how community benefits from the local ecotourism.

Community based ecotourism in the area contributes for community benefit in various ways. One of the main benefits for participants is economic values. Whilst, nonparticipants stated as they enjoy benefits such as natural and environmental services from ecotourism. Similarly, some interviewees from participants and nonparticipants revealed the natural values of the ecotourism destination. Ecosystem services such as climate regulation, provision of clean air and water, soil protection, and pollination are values enjoyed by communities. Variations in terms of benefits obtained are observed between participants and nonparticipants. Our study indicated as local people do value conservation areas for non-economic reasons, such as ecosystem and environmental services. This is congruent to the study of Snyman [18], in which many felt in that ecotourism was important for their children and future generations, as well as for the wood, thatch and food it provides. In the study area, the ecotourism benefits for communities include economic, social, natural and capacity building. If ecotourism is properly managed and applied, it is valuable in providing economic benefits; social benefits and promoting environmental benefits through conservation [2]. The other aspect of community benefit from ecotourism in the area is capacity building which is higher among participants than nonparticipants. This is in line with the study of Bynoe [19], in which community-based ecotourism enhanced human capital through education and skills, and increased greater interaction among households in Surama, Guyana, that led to positive perception towards ecotourism by the majority of participant communities. Stakeholders will only be able to work in cohesion when there is a greater awareness among community about the benefits of community based ecotourism. Hence, capacity building through training and education are important aspects in community based ecotourism [20].

The effect of ecotourism benefits on the perception of participants and nonparticipants: In the study area, participant communities obtain a higher amount of economic benefits while nonparticipants enjoy minimal benefits from community based ecotourism. According to nonparticipants, the major benefit they obtain from ecotourism relates to environmental services. As a result, the perception of participant communities towards community based ecotourism was characterized by a positive response of ecotourism economic benefits. While the perception of nonparticipant communities towards community based ecotourism was characterized by a negative response of ecotourism economic benefits. In the same manner, the importance of community based ecotourism in resource conservation and livelihood improvement is higher in participants. But, both participants and nonparticipants relatively equally revealed the importance of ecotourism in societal development of the community (Table 4).

| Perception | Non-Participant | Participant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | NK (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | NK (%) | |

| CBECT promotes conservation | 31.13 | 54.72 | 14.15 | 89.72 | 8.41 | 1.87 |

| CBECT enhances societal development | 53.77 | 7.55 | 38.68 | 75.70 | 4.67 | 19.63 |

| CBECT contributes for local livelihood improvement | 22.64 | 55.66 | 21.70 | 82.24 | 8.41 | 9.35 |

CBECT: Community based ecotourism; %: Percentage; NK: Not Known

Table 4: The perception of communities towards community based ecotourism importance.

The attitude of communities towards community based ecotourism importance for livelihood improvement indicated the greater positive response of participants compared to the nonparticipant groups. Similarly, the attitude of communities towards ecotourism importance for conservation was characterized by positive response of participants compared to nonparticipants [21]. Local residents view ecotourism less favorably if ecotourism in the area doesn’t bring equitable and sufficient benefits [22]. Similarity, nonparticipant communities are unlikely to support conservation and sustainable management of natural areas due to insufficient direct benefit they receive from ecotourism [22]. Although CBET is necessary in promoting a win-win situation in community development and biodiversity conservation, it may not always bring intended outcomes as it is not neutral, but practiced in contested environments [12]. In our study site CBET is not uniformly perceived between participants and nonparticipants and varies between groups. This is due to the way ecotourism supports livelihood differs between ecotourism participants and nonparticipants. Based on this result, we have developed a conceptual framework illustrating the effect of local involvement variation in community based ecotourism (Figure 2).

Strengths and weaknesses of the community based ecotourism project

Strengths of the community based ecotourism project: The authors identified the strengths and weaknesses from the internal environment (interior factors) of the ecotourism initiative in the area (Tables 5 and 6).

| Strengths of CBET | Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | (%) | NNP | (%) | |

| Provision of economic benefits | 21 | 19.63 | 9 | 8.49 |

| Promoting experience sharing for communities | 28 | 26.17 | 8 | 7.55 |

| Working for sustainable utilization of resource | 5 | 4.67 | 3 | 2.83 |

| Working with community | 40 | 37.38 | 10 | 9.43 |

| Endorsement of supporting rules | 11 | 10.28 | 5 | 4.72 |

| Not stated | 2 | 1.87 | 71 | 66.98 |

NP: Number of participants; NNP: Number of nonparticipants; %: Percent

Table 5: The strengths of community based ecotourism in the area.

| Weaknesses of CBET | Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | (%) | NNP | % | |

| Lack of technical know-how and weak promotional activity | 11 | 10.28 | 14 | 13.21 |

| Inadequate tourist facility | 8 | 7.47 | 17 | 16.04 |

| Insufficient implementation of the CBECT program | 30 | 28.04 | 26 | 24.53 |

| Inadequate resource management | 23 | 21.50 | 18 | 16.98 |

| Lack of common governing rule | 26 | 24.30 | 25 | 23.58 |

| Other (finance, absence of team work, etc.) | 9 | 8.41 | 6 | 5.66 |

NP: Number of participants; NNP: Number of nonparticipants; %: Percent

Table 6: The weaknesses of community based ecotourism in the area.

Working with community, promoting experience sharing for communities and provision of economic benefits are the major strengths of the ecotourism initiative according to participants. In contrast, nonparticipants stated as there is no major strengths of community based ecotourism. They described the existence of working with community, promoting experience sharing for communities and provision of economic benefits slightly. The response of participants is in line with the study of Oladeji [23], in which ecotourism increases awareness, benefit and pride of the local community since it creates a value for local knowledge. Whereas nonparticipants do not appreciate the strengths of ecotourism initiative likes participants. This might be due to they are economically disempowered and could not enjoy economic and other benefits of ecotourism [12]. All FGDs members supported the strengths of ecotourism initiative in working with community and promoting experience sharing for communities. As a result, the discussants revealed the increasing awareness of communities which made the communities look the wild animals and trees as their own children. Working for sustainable utilization of resource and endorsement of supporting rules are the low appreciated strengths of the ecotourism intervention program both by participants and nonparticipants.

Weaknesses of the community based ecotourism project: In the study area different weaknesses of the ecotourism program intervention were revealed both by participants and nonparticipants of the program. Both groups identified insufficient implementation of the CBECT program, inadequate resource management and lack of common governing rule as the top three weaknesses of the ecotourism initiative in the area. The discussion with focus groups supports this idea. FGD members in nonparticipant kebeles strongly claimed exclusion of some kebeles and blocks at the beginning of the program in which inadequate implementation of the CBECT intervention led conflicts to occur. On the other hand we found different responses from Adaba Woreda participants. The multidimensional FGD group organized in Bucha and Ejersa village indicated the failure to adequately implement the CBET program in selected blocks as planned by GTZ. Though, initially more than seven kebeles were being selected as intervention areas, currently only Bucha PA is the beneficiary, in a very dispersed and fragmented ways. Accordingly, the discussants recommended and supported the organized and fruitful implementation of such interventions with full commitments of all stallholders. Similarly, the interview with Genene, Manager of Adaba-Dodola district forest and wildlife enterprise revealed the need to promote the implementation of CBET depending on current coverage of the protected areas by PAs and respective blocks. Insufficient implementation of the CBECT program in the area might be associated with lack of financial access. The ability to access finance to support ecotourism investment programmes is a big barrier to the success of CBET in the community. In addition, lack of financial resources limits the full participation of communities in CBET programmes [24]. Inadequate resource management and lack of common governing rules were admitted as weaknesses by respondents. This might also be associated with the presence nonparticipants which are not involved and not benefited from the ecotourism program, and that leads to conflict.

Lack of technical know-how and weak promotional activity, inadequate tourist facility, other weaknesses (i.e., finance, absence of team work, etc.) are also the limitations of ecotourism in the area. This is more similar to studies in other ecotourism sites in Ethiopia. Meniga and Ousman [2], discussed lack of technical know-how and weak promotional activity in ecotourism destinations in Ethiopia while Tesfaye [25], found that most of the ecotourism destinations in Ethiopia are devoid of tourist facilities and services. According to Asuk and Nchor [24], lack of basic tourism infrastructure and facilities affect the operation of CBET. These facilities may include tourist chalets, restaurants, electricity, clean water supply, poor communication facilities and laterite roads. Lack of adequate teamwork among stakeholders has also been described as weakness since it affects ecotourism development [26].

Conclusion

Adaba-Dodola community based ecotourism is one of the ecotourism initiatives in Ethiopia established to improve the local communities’ livelihood through ecotourism and promoting the sustainable conservation of biodiversity. As the present study indicates, ecotourism in the area brought inequalities between participants and nonparticipants in economic benefits. Participants support the importance of ecotourism to local livelihood improvement and promotion of conservation. Whereas nonparticipants supported the natural and ecosystem services obtained from ecotourism destinations. This has affected communities’ perception of ecotourism and its role. Majority of nonparticipants have not reported any adequate strengths of the community based ecotourism project while working with community has been the strength supported by participants. Both participants and nonparticipants revealed insufficient implementation of the CBECT program as the main weakness that need to be improved in the area.

Recommendation

The participation and collaboration of different ecotourism stakeholders is suggested to promote adequate implementation of the CBECT program. Awareness creation and trainings should be offered to nonparticipants to enhance cooperation with participants. Moreover, effort should be made to indirectly link nonparticipants with ecotourism through provision of agricultural and traditional crafts for tourist as they support the local livelihood in a good manner.

Acknowledgements

We forward our gratitude to Madda Walabu University for providing fund to conduct the study. We are grateful to OFWE of Dodola branch for granting permission to conduct the research. We are extremely grateful to workers of OFWE and the local people for their hospitality and willingness to share their information. We also would like to acknowledge workers of OFWE in Dodola district for their unreserved contribution during the study period.

References

- The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) (2006) Community based ecotourism: Best practice stories and resources. Digital Traveler and Asia Pacific eNewsletter, pp: 37-46.

- Meniga M, Ousman J (2017) Problems and prospects of community-based ecotourism development in Ethiopia. Glob J Res Analy 6: 459-462.

- Kaplan S (2013) Community based ecotourism for sustainable development in eastern black sea region an evaluation through local communities tourism perception (PhD Thesis), Middle East Technical University, Turkey.

- Rajasenan D, Paul BP (2012) Standard of Living and Community Perception in the Community Based Ecotourism (CBET) Sites of Kerala: An Inter Zone Analysis. J Economics Sustainable Dev 3: 18-28.

- Ondicho TG (2012) Local Communities and Ecotourism Development in Kimana, Kenya. J Tourism 13: 41-59.

- Falcett A (2012) Perceptions of Conservation and Ecotourism in the Taita-Taveta County, Kenya (Master’s Thesis & Specialist Projects), Western Kentucky University, Kentucky.

- Tilleman F, Marcharis M (2017) The road towards community based Ecotourism. Maastricht Univ J Sust Stud 3: 17-30.

- Khan MM (1997) Tourism development and dependency theory: Mass tourism vs ecotourism. Annals Tourism Res 24: 988-991.

- Belsky J (1999) Misrepresenting communities: The politics of community-based rural ecotourism in gales point manatee. Belize Rur Socio 64: 641-666.

- Sundufu AJ, James MS, Foday IK, Kamara TF (2012) Influence of Community Perceptions towards conservation and eco-tourism benefits at Tiwai Island Wildlife Sanctuary, Sierra Leone. Amer J Tour Manag 1: 45-52.

- Snyman SL (2012) The role of tourism employment in poverty reduction and community perceptions of conservation and tourism in Southern Africa. J Sust Tour 20: 1-22.

- Stone MT (2015) Community Empowerment through Community-Based Tourism: The Case of Chobe Enclave Conservation Trust in Botswana. In: Institutional Arrangements for Conservation, Development and Tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa, pp: 81-100.

- Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise (2013) Participants of the Adaba-Dodola community based ecotourism. Report paper.

- Central Statistics Agency (2007) Central Statistics Agency of Ethiopian, Population Census.

- Teshome T (1999) Effect of grazing and fire on tree regulation in conference mountain forest of Adaba-Dodola area in Ethiopia (MA Thesis), Gottingen, Germany.

- Asfaw S (2004) Adaba-Dodola community-based eco-tourism development. A report paper, pp: 1-14.

- Cocheran WG (1977) Sampling technique (3rdedn), Jhons and Sons, NewYork.

- Snyman S (2014) Assessment of the main factors impacting community members attitudes towards tourism and protected areas in six Southern African countries, Koedoe-African Protected Area Conservation and Science56: 1-12.

- Bynoe P (2009) Whither Community Based-Ecotourism as a Sustainable Development Driver: The case of Surama, Guyana. In: International Conference Turtle Conservation, Ecotourism and Sustainable Community Development, Learning Resource Centre.

- Gupta SK, Rout RC (2016) The value chain approach in community based ecotourism: a conceptual framework on sustainable mountain development in the Jaunsar-Bawar region of Uttarakhand. Amit Res J Tour Aviat Hosp 1: 27-38.

- Menbere IP, Abie K, Tadele H, Gebru G (2018) Community based ecotourism and its role in local benefit and community perceptions of resource conservation: A Case study in Adaba-Dodola Districts, South Ethiopia. J Tour Hosp Spor 38: 15-28.

- Abeli SR (2017) Local communities perception of ecotourism and attitudes towards conservation of Lake Natron Ramsar Site, Tanzania. Int J Hum Soc Sci 7: 162-176.

- Oladeji SO (2015) Community based ecotourism management practice, a panacea for sustainable rural development in Liberia. J Res Fores Wild Environ 7: 136-153.

- Asuk SA, Nchor AA (2018) Challenges of community-based ecotourism development in Southern Eastern Nigeria: Case Study of Iko Esai Community. J Sci Res Rep 20: 1-10.

- Tesfaye S (2017) Challenges and opportunities for community based ecotourism development in Ethiopia. Afri J Hosp Tour Leis 6: 1-10.

- Menbere IP, Menbere TP (2017) Opportunities and challenges for community-based ecotourism development: A case study in Dinsho and Goba Woredas, Southeast Ethiopia. Int J Ecol Ecosolution 4: 5-16.

Citation: Menbere IP, Abie K, Tadele H, Gebru G (2019) The Impact of Variant Local Involvement in Community Based Ecotourism: A Conceptual Framework Approach. J Ecosys Ecograph 9: 261.

Copyright: © 2019 Menbere IP, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 2019

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Mar 31, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1265

- PDF downloads: 754