Research Article Open Access

The H-Scan Format for Classification of Ultrasound Scattering

Parker KJ*Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- Parker KJ

University of Rochester

Hopeman Building 203, P.O. Box 270126

Rochester, NY, 14627-0126, USA

Tel: +1-585-275-3774

Fax: +1-585-273-4919

E-mail: kevin.parker@rochester.edu

Received Date: September 01, 2016; Accepted Date: October 21, 2016; Published Date: October 27, 2016

Citation: Parker KJ (2016) The H-Scan Format for Classification of Ultrasound Scattering. OMICS J Radiol 5:236. doi: 10.4172/2167-7964.1000236

Copyright: © 2016 Parker KJ. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Radiology

Abstract

The H-scan is based on a simplified framework for characterizing scattering behavior, and visualizing the results as color-coding of the B-scan image. The methodology begins with a standard convolution model of pulse-echo formation from typical situations, and then matches those results to the mathematics of Gaussian Weighted Hermite Functions. In this framework, echoes can be classified as returning from specific categories of scatterers, and these can be conveniently displayed as colors. Thus, some information not evident in conventional grayscale pulse-echo images can be visualized in the H-scan format.

Keywords

Ultrasound; Imaging; Tissue characterization; Scattering; Hermite functions

Introduction

Traditional B-scan images show the envelope of received echoes as a grey scale image. The echoes are produced from specular reflections and scattering sites where changes in acoustic impedance occur [1,2]. A long-standing area of interest concerns the frequency dependence of scatterers within different tissues, organs, and the blood. Some tissue characterization techniques estimate the frequency dependence and angular dependence of backscattered waves, and an excellent overview of these is found in Chapter 9 of Szabo [3] and in Mamou and Oelze [4]. Statistical averaging techniques require some region of interest over which to calculate the expected value of scattering parameters. The statistics of ultrasound echoes [5,6] can limit the spatial resolution or accuracy of these estimators.

In comparison, the H-scan is an alternative where the received echoes can be linked to three major classes of signals from tissues. Echoes are linked to the mathematics of Gaussian Weighted Hermite Polynomials so that the overall identification task can be simplified. The resulting images are denoted as H-scans, where ‘H’ represents Hermite or hue, since the identification by hue is distinct from the traditional B-scan. Comparisons are shown where H-scan colors indicate specific scattering classes. A preliminary overview of the H-scan concept was given in Parker, 2016 [7]. The results have now been expanded along theoretical and experimental lines. In this paper, the analytic derivation of the expected outputs for three cases are deduced using the convolution model and the properties of the Dirac delta function and its derivatives, which then set the order of the Gaussian weighted Hermite functions. The model is applied to comparisons in biological tissues, specifically liver and placenta, where changes in tissue H-scan images are plausibly linked to changes in the concentration of small scatterers.

Theory

Pulse-echo convolution models

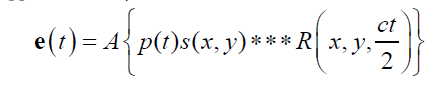

The pulse-echo A-line can be modeled as a convolution of an incident pulse with a sequence of reflections [2,8]. Assuming sufficiently weak attenuation, backscatter, and focusing, the echo formation can be reduced to a convolution model [8] such that the received echo e(t) is approximated by

where A is an amplitude constant, p(t) is the propagating pulse in the axial direction z , s ( x, y) is the beam width in the transverse and elevational axes (and thus the beam pattern is assumed to be a separable function) and R( x, y, z ) is the 3D pattern of reflectors or scatterers. The speed of the sound is c, and accounting for the round trip for the echo, the axial distance z is replaced by ct/2 in the 3D convolution represented by the symbol *** . The assumptions inherent in the convolution model are reasonably met in many conventional scanning systems, for example a 5 MHz center frequency f /2 system with common apodization functions focused at 5 cm depth as analyzed in Chen and Parker [9].

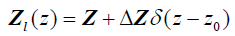

In simplified one-dimensional derivations with an assumption of small spatial variations in density and compressibility;  and

and  , respectively, then the function R( z ) can be related to the spatial derivative of acoustic impedance Z = ρc in the direction z of propagation of the imaging pulse [2]:

, respectively, then the function R( z ) can be related to the spatial derivative of acoustic impedance Z = ρc in the direction z of propagation of the imaging pulse [2]:

(2)

(2)

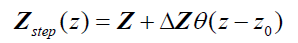

Now consider three simple types of reflections in a one-dimensional convolution model. Let

(3)

(3)

where θ (z) is the Heaviside unit step function and  . This represents a small step increase in acoustic impedance at position

. This represents a small step increase in acoustic impedance at position  . An example of this would be the interface between venous blood and solid organs. Accordingly, the reflection coefficient at

. An example of this would be the interface between venous blood and solid organs. Accordingly, the reflection coefficient at  will be proportional to the spatial derivative of impedance, and combining eqn (2) and (3) we have:

will be proportional to the spatial derivative of impedance, and combining eqn (2) and (3) we have:

(4)

(4)

where  is the Dirac delta function, the derivative of the unit step function [10]

is the Dirac delta function, the derivative of the unit step function [10]

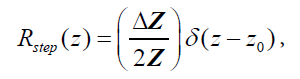

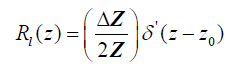

Next, consider a thin material of higher acoustic impedance ΔZ , such as an arterial wall. In the limit, as the front and back walls are located closer together, we can approximate the impedance profile as:

(5)

(5)

and therefore, using eqn (2), the reflection function is:

(6)

(6)

where  is the “doublet” or the derivative of the Dirac delta function [10].

is the “doublet” or the derivative of the Dirac delta function [10].

Finally, in more general scattering theory, the Born approximation for a small (subwavelength) spherical scatterer has a leading term for backscattered pressure that is proportional to  [2,11], where

[2,11], where is the radius of the spherical inhomogeneity. These are commonly called Rayleigh scatterers [11]. Furthermore, a low number density of small, weak scatterers, incoherently spaced, similarly has a scattered pressure dependence with a leading term proportional to

is the radius of the spherical inhomogeneity. These are commonly called Rayleigh scatterers [11]. Furthermore, a low number density of small, weak scatterers, incoherently spaced, similarly has a scattered pressure dependence with a leading term proportional to  [11]. In these classical derivations, the density and compressibility change within the scatterer are assumed to be small compared to the reference media values; furthermore the scatterers are small compared to the wavelength of the ultrasound pulse, and the number density is small enough so that position correlation and multiple reflections can be ignored [2,11]. Larger scatterers and random collections of scatterers with spatial correlation functions will have more complicated scattering vs. frequency formulas [12-21].

[11]. In these classical derivations, the density and compressibility change within the scatterer are assumed to be small compared to the reference media values; furthermore the scatterers are small compared to the wavelength of the ultrasound pulse, and the number density is small enough so that position correlation and multiple reflections can be ignored [2,11]. Larger scatterers and random collections of scatterers with spatial correlation functions will have more complicated scattering vs. frequency formulas [12-21].

However, the ω2 frequency weighting is an important analytical endpoint because by Fourier Transform theorems, an ω2 weighting corresponds to the second derivative of a function:

(7)

(7)

Furthermore, ω2 frequency weighting is equivalent to convolution with  , the second derivative of the Dirac doublet function [22]; i.e.,

, the second derivative of the Dirac doublet function [22]; i.e.,

(8)

(8)

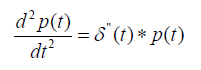

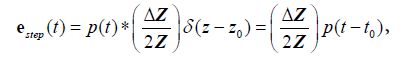

Now to summarize these results in a one-dimensional convolution model, we have for a step function interface:

(9)

(9)

where  and the sifting property of convolution with a delta function [10,22] is applied.

and the sifting property of convolution with a delta function [10,22] is applied.

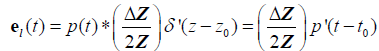

For the thin layer reflection:

, (10)

, (10)

where  is the first derivative with respect to time of p(t) obtained from the convolution property of the

is the first derivative with respect to time of p(t) obtained from the convolution property of the  function [10,22].

function [10,22].

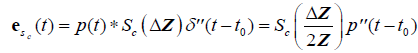

Finally, for a single Rayleigh scatterer or cloud of scatterers:

, (11)

, (11)

where  is the second derivative of p(t) with respect to time, obtained from the convolution property of

is the second derivative of p(t) with respect to time, obtained from the convolution property of  , and where Sc incorporates all geometric factors and constants of proportionality in the Rayleigh backscatter equation [11].

, and where Sc incorporates all geometric factors and constants of proportionality in the Rayleigh backscatter equation [11].

Given these three results, the next task is to seek to identify echoes by their relationship to the transmitted pulse and its derivatives. A family of functions related to the Hermite polynomials is one convenient way to do this.

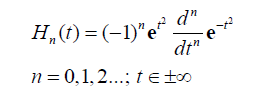

Gaussian weighted Hermite polynomials

The successive differentiation of the Gaussian pulse e(-t2) generates the nth order Hermite polynomial (see Table 1 of Poularikas) [23]. The Hermite polynomials are defined by the formula

(12)

(12)

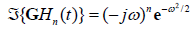

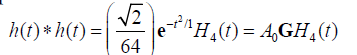

When multiplied by an envelope  , these become the Gaussian weighted Hermite polynomials. For instance,

, these become the Gaussian weighted Hermite polynomials. For instance,  and its energy

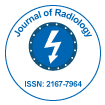

and its energy . This is shown in Figure 1, compared with a familiar bandpass model

. This is shown in Figure 1, compared with a familiar bandpass model  . The Fourier transform of

. The Fourier transform of  is

is  , and in general,

, and in general, , consistent with their relationship with respect to time derivative:

, consistent with their relationship with respect to time derivative:

.

.

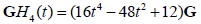

Also, the  function resembles a typical broadband pulse as shown in Figure 1. If a transducer element has a one-way transfer function of

function resembles a typical broadband pulse as shown in Figure 1. If a transducer element has a one-way transfer function of

(13)

(13)

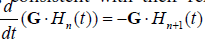

then it can be shown that the two-way (transmit-receive) impulse response is:

(14)

(14)

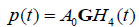

Let us assume a pulse-echo system with a round trip impulse response of  , then from the logic of eqn (9), (10), and (11) we have for the echoes from the step, the thin layer, and the Rayleigh scatterer:

, then from the logic of eqn (9), (10), and (11) we have for the echoes from the step, the thin layer, and the Rayleigh scatterer:

(15)

(15)

respectively, where the derivative identities of the  functions are used. The relationships are summarized in Figure 2.

functions are used. The relationships are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Schematic for pulse-echo relations from (a) reflection from a boundary between two media with small change in acoustic impedance. The reflection R is modeled as a delta function. In (b) a thin layer of elevated impedance is modeled, in the limit, as a reflection related to a doublet (the derivative of the Dirac delta function). In (c) a small Rayleigh scatterer has a reflection with the leading term related to a second derivative with respect to time. If the transmitted pulse is a GH4 function, then the three cases return a GH4, a GH5, and a GH6, respectively. The classification task is then simplified to identification of these three signals.

In this formulation, the received echoes can be classified by similarity to either  . A natural classification test employing the concept of M-ary optimum receivers or matched filters [24] or maximum likelihood filters [25] would suggest a convolution of the received signal with scaled versions of

. A natural classification test employing the concept of M-ary optimum receivers or matched filters [24] or maximum likelihood filters [25] would suggest a convolution of the received signal with scaled versions of  to form three post-processed signals. Some classification approaches simply select the maximum value at each point in time or display the relative strength as colors, as shown in Figure 3(a).

to form three post-processed signals. Some classification approaches simply select the maximum value at each point in time or display the relative strength as colors, as shown in Figure 3(a).

Figure 3: (a) Schematic for parallel processing and display of received echoes e(t). Convolution with a lower frequency and lower order GWHF is assigned red, and higher frequency/higher order GWHF assigned blue. In (b) the envelope is used for green and retains the highest original axial resolution.

However, each convolution results in some loss of resolution, and the cross-correlation terms between  and

and  and similarly for

and similarly for  and

and  are substantial due to the significant overlap of spectra. To address this, some compromises can be made. One approximate approach uses the standard envelope as intensity (or “G” in RGB) with two parallel convolution filters applied to gage the relative strength of the echoes with respect to

are substantial due to the significant overlap of spectra. To address this, some compromises can be made. One approximate approach uses the standard envelope as intensity (or “G” in RGB) with two parallel convolution filters applied to gage the relative strength of the echoes with respect to  and

and  .

.

In practice, cross-correlation can be further decreased by using more emphasis on the extremes of the spectra, for example by employing  and

and  to capture the low and high frequencies, respectively, each normalized by

to capture the low and high frequencies, respectively, each normalized by  . The simplified flow chart is shown in Figure 3(b). It is possible to consider even more extreme examples, for example H9 or H10 or higher orders replacing H6, but this deviates further from the matched filter concept and adds sensitivity to high frequency noise. Thus, tradeoffs and compromises must be considered.

. The simplified flow chart is shown in Figure 3(b). It is possible to consider even more extreme examples, for example H9 or H10 or higher orders replacing H6, but this deviates further from the matched filter concept and adds sensitivity to high frequency noise. Thus, tradeoffs and compromises must be considered.

Alternatively, the ratios of the H2/H8 or H8/H2 convolution outputs can be taken and used as weights for the “R” and “B” channels, respectively. The lower frequency (H2) is assigned to R and the higher frequency (H8) is assigned to B in accordance with visual perception of scattered light.

Results

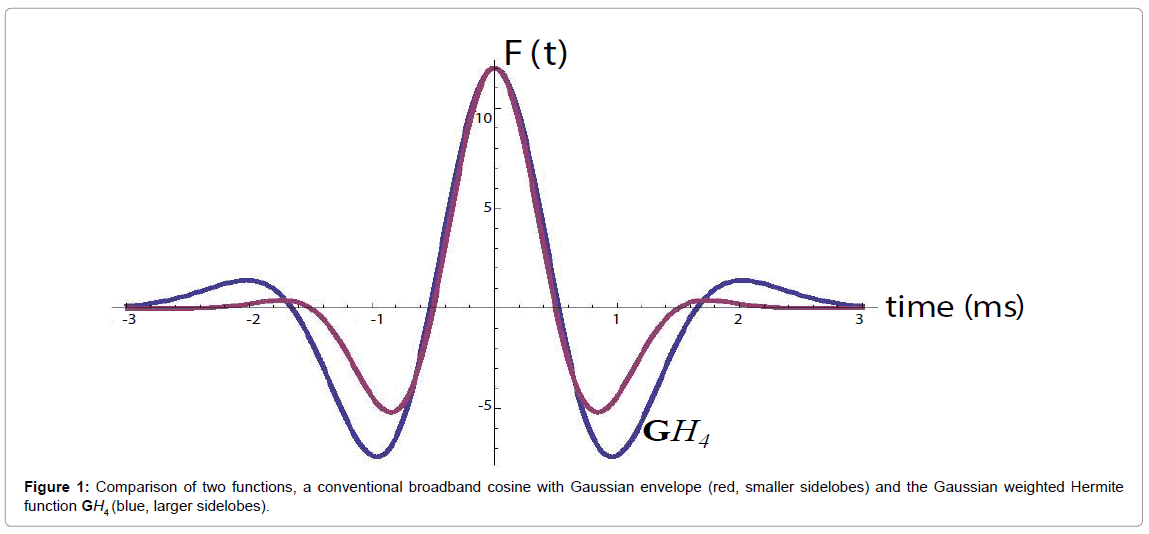

In the following example, conventional B-scans are obtained using a Verasonics scanner with a 5 MHz ATL linear array transducer (Verasonics, Inc., Kirkland, WA, USA), with the RF sampled at 12 bits at 20 MHz. Although conventional systems do not transmit a precise  function, the transmitted pulse is sufficiently similar. An approximate analysis can be performed using the H2 and H8 correlation functions and then assignment of colors as described previously. In the following examples, the grey scale image represents the conventional appearance of the B-scan using standard 50 dB dynamic range on the echo envelope. The color images demonstrate ratios of convolutions with GH2 and GH8 outputs, assigned to red and blue channels, respectively.

function, the transmitted pulse is sufficiently similar. An approximate analysis can be performed using the H2 and H8 correlation functions and then assignment of colors as described previously. In the following examples, the grey scale image represents the conventional appearance of the B-scan using standard 50 dB dynamic range on the echo envelope. The color images demonstrate ratios of convolutions with GH2 and GH8 outputs, assigned to red and blue channels, respectively.

In order to test the analysis on random spherical scatterers, 10% gelatin phantoms were constructed with 1% by weight suspension of soft clear polyethylene microspheres (CoSpheric LLC, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). On the left side of the phantom in Figure 4 are smaller 25 μm scatterers, (range 10-63 μm), and on the right side are larger 530 μm scatterers (range 500-600 μm). The transmit energy and receive gain were set to maintain the larger (brighter) echoes at an amplitude approximately 20 dB below saturation of the echo signals. The conventional B-scan illustrates some difference in echogenicity on the left vs. right sides of the phantom. Moreover, the convolution with Hermite functions highlights the different frequency weighting of the scatterer types, as seen by the more dominant blue color on the left (small scatterers), and a more dominant orange/pink on the right (large scatterers).

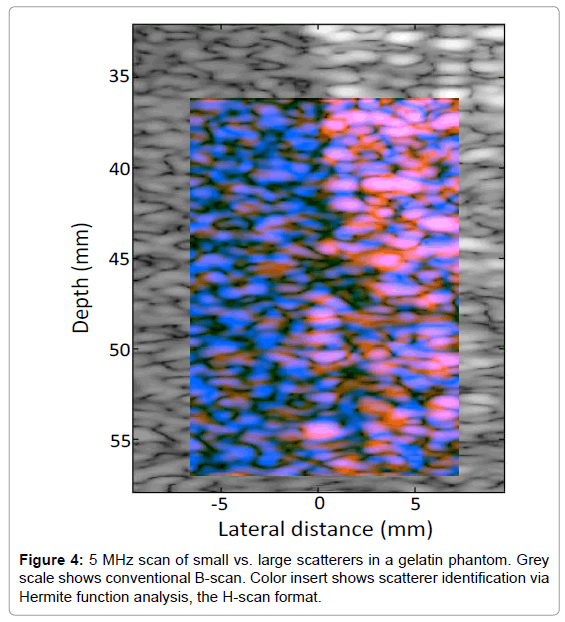

H-scan images of tissues also can demonstrate color patterns that appear to be related to the underlying scattering behavior. A perfused, living, placenta model ex vivo [26] was imaged using protocol approved by the Research Subjects Review Committee at the University of Rochester. Placental anatomy is shown in Figure 5. For B-scans, the whole placenta is perfused via umbilical arteries and placed in a 37ºC water bath with the chorionic plate facing up towards the imaging transducer [26].

Figure 5: Example of placental anatomy. In (a) the whole post-delivery placenta is shown with chorionic plate with umbilical arterial branches facing up. The umbilical cord is separated for examination. In (b) the placenta has been sectioned for gross pathology. Images courtesy of Drs. P. J. Katzman and R. K. Miller of the University of Rochester.

An example of a placenta cross section is shown in Figure 6, where baseline images (Figure 6a for H-scan and Figure 6c for B-scan) demonstrate largely green channel echoes in the normal fetal side parenchyma using a 5 MHz broadband linear array transducer and the Siemens Antares scanner, sampled as 16 bit RF at 40 MHz. Later, after injection of a potent vasoconstrictor agent, and then Optison contrast agent, and after a further delay of approximately 2 min, the H-scan image Figure 6b has an enhanced blue channel signal (high frequency) and the B-scan (Figure 6d) demonstrates increased echogenicity. The likely reason for the increased echogenicity and increased blue scatterer strength is retention of the Optison contrast agent in the microvasculature under the effects of the vasoconstrictor. Bubble contrast agents small enough to flow through capillaries (under 10 microns diameter) would be Rayleigh scatterers at 5 MHz (wavelength approximately 300 microns in tissue). In addition, nonlinear response of bubbles can create sub- and higher harmonics [27,28]. The higher harmonics would add to the blue channel signal.

Figure 6: 5 MHz H-scans and B-scans of living, perfused placenta, ex vivo and immediately post-delivery. The chorionic plate is up and the maternal side down in this experiment. (a) and (c) are the baseline case, while (b) and (d) are after injection of a vasoconstrictor agent, followed by a bolus of Optison contrast agent, followed by a short delay. In the latter scan, the echogenicity increases and the blue (or high frequency result of GH8 convolution) speckle strength increases. This is likely related to the effect of the contrast agent as a Rayleigh scatterer.

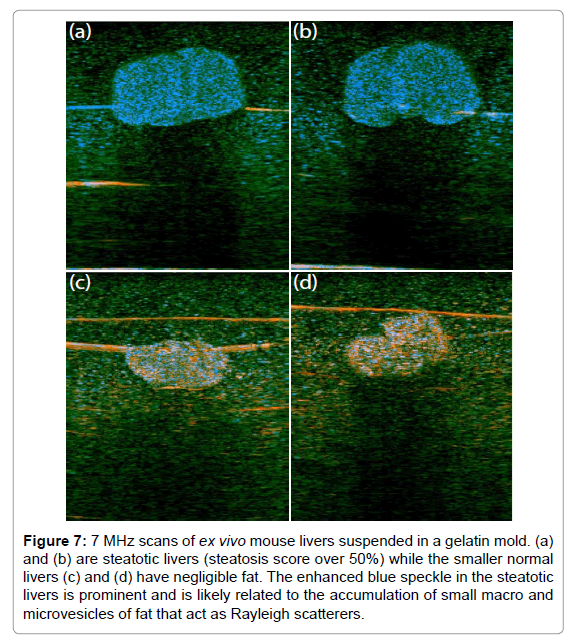

Mouse livers, ex vivo, are shown in Figure 7, imaged using a GE LOGIQ 9 scanner with a 7 MHz linear array probe and digitized as 16 bit I and Q at 5.7 Mhz. This study was conducted under a research protocol approved by the University of Rochester Committee on Animal Resources. These scans were selected at random from a larger elastography study of shear wave speeds in normal vs. fatty (steatosis) livers [29,30]. H-scan images of fatty livers (Figures 7a and 7b) and of normal livers (Figures 7c and 7d) are shown. The fatty livers are larger and have a preponderance of blue channel (GH8 or high frequency) speckle compared with the normal. This could be the result of the accumulation of microvesicles of fat, typically below 8 microns in diameter, which act as Rayleigh scatterers. The horizontal lines in these figures are the result of a fine thread used to suspend the livers in agar gel, and also reverberation from the sample floor echo.

Figure 7: 7 MHz scans of ex vivo mouse livers suspended in a gelatin mold. (a) and (b) are steatotic livers (steatosis score over 50%) while the smaller normal livers (c) and (d) have negligible fat. The enhanced blue speckle in the steatotic livers is prominent and is likely related to the accumulation of small macro and microvesicles of fat that act as Rayleigh scatterers.

Discussion

The H-scan derivations are limited by the use of simplified models of pulse echo formation and reflections. This does not capture the angular dependence of reflections from specular reflectors, nor the more general frequency-dependent behavior of scattering from correlated random variations in density and compressibility as demonstrated by k-space analysis and measurements [14,16] or by more rigorous quantitative backscatter techniques [4,17,18,31-36]. The simplified model of Figure 2 does not consider the cumulative effects of frequency-dependent attenuation. Thus, the Hermite analysis is more simplified but has high spatial resolution.

In viewing the H-scan images, some caution should be noted. As the received echo strength approaches maximum value, the display reverts to saturated white. Some additional normalization and comparison steps could be added to mitigate this nearer to the limits, but amplifier and display limits will always be present. Each of the output images shown have been displayed on a 50 dB dynamic range scale, and as with B-scan displays this is adjustable and can skew imageto- image comparisons depending on the peak values found within each scan. Another effect is the presence of dominant vs. residual colors that can be seen within isotropic scatterers in Figure 4 and in previous simulations [7]. Evidently, the constructive and destructive interference of subresolvable scatterers, plus frequency-dependent beam-width effects (higher frequencies have tighter focus) can play a role in creating residual colors interspersed within a dominant scheme. Similar effects could exist in tissue and so interpretation of color mosaics may be complicated. Further research is required to delineate these effects and to determine the sensitivity of the approach to more subtle changes in reflection and scattering distributions. Also, some training and experience will be required to interpret the color schemes in specific organs.

The results from Hermite analyses raise the issue of alternative approaches. Among these, Wavelets, narrowband frequency compounding, and Fourier analyses are commonly used in digital signal processing to examine the frequency content of signals.

Wavelet analyses [37] are widely used for a range of imaging applications, and have been applied to ultrasound images and RF data [38,39] for classification and speckle reduction. Within the class of orthonormal, multi-resolution wavelet families, low pass and high pass versions exist [37] which could provide useful frequency analyses. Scalable Hermite families also exist for Wavelet analyses [40] so analogous orders of Hermite functions could be implemented within a wavelet analysis framework. Narrowband frequency analysis [41,42] of RF echoes and the closely related Fourier analyses [4] provide frequency specificity but can degrade axial resolution. However, if an appropriate Hermite function can be transmitted, then the H-scan approach has the advantages of the exact derivative nature of the Hermite orders providing exact matched filters for the three specific classes in Figure 2. A detailed quantification of tradeoffs is left for future research.

Another question is the need for transmitted pulses to be close approximations of the GH4 function as shown in Figure 1. The Results section includes analyses from three different and widely used scanning platforms. Each one produces a broad band pulse but there were no special waveform modifications used. This suggests a robustness of the analysis with respect to deviations from the ideal Hermite pulse. In terms of signal processing, as the transmitted signal’s time domain and frequency domain values deviate from the ideal Hermite function increases, the precise time derivative relations and matching filter behavior will degrade. An analysis of the degradation will require further research.

Conclusion

Within a simplified framework, we match a convolution model of pulse reflections to the mathematics of Gaussian Weighted Hermite Functions. By interpreting and displaying the echoes according to their similarities to expected orders of the Hermite functions, this process enables the recognition of an added dimension as each region of the echoes are characterized by their low (red), medium (green), or high (blue) frequency content as determined by the impedance function present in tissue along the direction of the propagating pulse. The examples suggest that the H-scan can provide a deeper understanding of how variations in B-scan appearance are linked to underlying scatterer classes.

Acknowledgement

Thanks are due to Ph.D. student Shujie Chen in programming the Verasonics scanner (Verasonics, Inc., Kirkland, WA, USA) and Mathematica notebooks (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL, USA), greatly speeding the progress of this project. Graduate student Juvenal Ormachea and Dr. Zaegyoo (Jay) Hah acquired data on the placentae and livers. This work was supported by the Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at the University of Rochester.

References

- Prince JL, Links JM (2006) Ultrasound imaging systems, Medical Imaging Signals and Systems, Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Cobbold RSC (2007) Foundations of biomedical ultrasound, Biomedical engineering series, Oxford University Press, New York.

- Szabo TL (2004) Diagnostic ultrasound imaging: Inside Out, Academic Press series in biomedical engineering, Elsevier Academic Press, Burlington, USA.

- Mamou J, Oelze ML (2013) Quantitative Ultrasound in Soft Tissues, Springer, Netherlands.

- Burckhardt CB (1978) Speckle in ultrasound B-mode scans. IEEE Trans Sonics Ultrason 25: 1-6.

- Lizzi FL, Astor M, Feleppa EJ, Shao M, Kalisz A (1997) Statistical framework for ultrasonic spectral parameter imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol 23: 1371-1382.

- Parker KJ (2016) Scattering and reflection identification in H-scan images.Phys Med Biol 61: L20-L28.

- Macovski A (1983) Basic Ultrasonic Imaging: in Medical Imaging Systems.

- Chen S, Parker KJ (2016) Enhanced resolution pulse-echo imaging with stabilized pulses. Journal of Medical Imaging 3: 027003-027003.

- Cohen-Tannoudji C, Diu B, Laloë F (1976) Quantum mechanics.Wiley, New York.

- Morse PM, Ingard KU (1987) Theoretical Acoustics: In Theoretical Acoustics. Princeton University Press: Princeton, USA.

- Lerner RM, Waag RC (1988) Wave space interpretation of scattered ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol 14: 97-102.

- WaagRC, Lee PPK, PerssonHW, SchenkEA,Gramiak R (1982)Frequency-dependent angle scattering of ultrasound by liver. J AcoustSoc Am72: 343-352.

- Campbell JA, Waag RC (1983) Normalization of ultrasonic scattering measurements to obtain average differential scattering cross sections for tissues. J AcoustSoc Am 74: 393-399.

- Waag RC (1984) A review of tissue characterization from ultrasonic scattering. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 31: 884-893.

- Campbell JA, Waag RC (1984) Ultrasonic scattering properties of three random media with implications for tissue characterization. J AcoustSoc Am 75: 1879-1886.

- Mottley JG, Miller JG (1988) Anisotropy of the ultrasonic backscatter of myocardial tissue: I. Theory and measurements invitro. J AcoustSoc Am 83: 755-761.

- Mottley JG, Miller JG (1990) Anisotropy of the ultrasonic attenuation in soft tissues: Measurements invitro.. J AcoustSoc Am 88: 1203-1210.

- Nam K, Zagzebski JA, Hall TJ (2013) Quantitative assessment of in vivo breast masses using ultrasound attenuation and backscatter. Ultrason Imaging 35: 146-161.

- Destrempes F, Franceschini E, François TH, Cloutier G (2016) Unifying concepts of statistical and spectral quantitative ultrasound techniques. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 35: 488-500.

- Shung KK (2015) Diagnostic ultrasound: imaging and blood flow measurements. (2ndedn), CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA.

- Bracewell RN (1965) The Fourier transform and its applications. (1stedn), McGraw-Hill series in electrical engineering, Circuits and systems. New York.

- Poularikas AD (2010) Transforms and applications handbook. In The electrical engineering handbook series, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA.

- Lathi BP (1983) Modern digital and analog communication systems: In HRW series in electrical and computer engineering, Holt Rinehart and Winston, New York.

- Proakis JG (2001) Digital communications: In McGraw-Hill series in electrical and computer engineering, McGraw-Hill: Boston, USA.

- McAleavey SA, Parker KJ, Ormachea J, Wood RW, Stodgell CJ, et al. (2016) Shear Wave Elastography in the Living, Perfused, Post-Delivery Placenta. Ultrasound Med Biol 42: 1282-1288.

- Faez T, Emmer M, Kooiman K, Versluis M, van der Steen AF, et al. (2013) 20 years of ultrasound contrast agent modeling. IEEE Trans UltrasonFerroelectrFreq Control 60: 7-20.

- Peruzzini D, Viti J, Tortoli P, Verweij MD, de Jong N, et al. (2015) Ultrasound contrast agent imaging: Real-time imaging of the superharmonics, AIP: Écully, France.

- Barry CT, Hah Z, PartinA, Mooney RA, Chuang KH, et al. (2014) Mouse liver dispersion for the diagnosis of early-stage fatty liver disease: a 70-sample study. Ultrasound Med Biol 40: 704-713.

- Parker KJ, Ormachea J, McAleavey SA, Wood RW, Carroll-Nellenback JJ, et al. (2016) Shear wave dispersion behaviors of soft, vascularized tissues from the microchannel flow model. Phys Med Biol 61: 4890-4903.

- InsanaMF, WagnerRF, BrownDG,HallTJ (1990)Describing small-scale structure in random media using pulse-echo ultrasound. J AcoustSoc Am87: 179-192.

- FeleppaEJ, LiuT, KaliszA, ShaoMC, FleshnerN, et al. (1997) Ultrasonic spectral-parameter imaging of the prostate.Int J Imaging SystTechnol 8: 11-25.

- Lizzi FL, Astor M, Liu T, Deng C, Coleman DJ, et al. (1997) Ultrasonic spectrum analysis for tissue assays and therapy evaluation. Int J Imaging SystTechnol 8: 3-10.

- Oelze ML, Zachary JF, O’Brien WD (2002) Characterization of tissue microstructure using ultrasonic backscatter: Theory and technique for optimization using a Gaussian form factor. J AcoustSoc Am 112: 1202-1211.

- Lavarello RJ, Ghoshal G, Oelze ML (2011) On the estimation of backscatter coefficients using single-element focused transducers. J AcoustSoc Am 129: 2903-2911.

- Lavarello RJ, Ridgway WR, Sarwate SS, Oelze ML (2013) Characterization of thyroid cancer in mouse models using high-frequency quantitative ultrasound techniques. Ultrasound Med Biol 39: 2333-2341.

- Proakis JG (2001) Digital communications: In McGraw-Hill series in electrical and computer engineering. McGraw-Hill: Boston, USA.

- Cincotti G, Loi G, Pappalardo M (2001) Frequency decomposition and compounding of ultrasound medical images with wavelet packets. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 20: 764-771.

- Acharya UR, Faust O, Sree SV, Molinari F, Garberoglio R, et al. (2011) Cost-effective and non-invasive automated benign and malignant thyroid lesion classification in 3D contrast-enhanced ultrasound using combination of wavelets and textures: a class of ThyroScan algorithms. Technol Cancer Res Treat 10: 371-380.

- Martens JB (1990) The Hermite transform-theory. IEEE Trans Acoustics, Speech, Signal Processing 38: 1595-1606.

- Sanchez JR, Oelze ML (2009) An ultrasonic imaging speckle-suppression and contrast-enhancement technique by means of frequency compounding and coded excitation. IEEE Trans UltrasonFerroelectrFreq Control 56: 1327-1339.

- Trahey GE, Allison JW, Smith SW, Von Ramm OT (1986) A quantitative approach to speckle reduction via frequency compounding. Ultrason Imaging 8: 151-164.

Relevant Topics

- Abdominal Radiology

- AI in Radiology

- Breast Imaging

- Cardiovascular Radiology

- Chest Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- CT Imaging

- Diagnostic Radiology

- Emergency Radiology

- Fluoroscopy Radiology

- General Radiology

- Genitourinary Radiology

- Interventional Radiology Techniques

- Mammography

- Minimal Invasive surgery

- Musculoskeletal Radiology

- Neuroradiology

- Neuroradiology Advances

- Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology

- Radiography

- Radiology Imaging

- Surgical Radiology

- Tele Radiology

- Therapeutic Radiology

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14025

- [From(publication date):

October-2016 - Mar 29, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 13013

- PDF downloads : 1012