The Effect of Brief Health Education Videos on High School Students

Received: 26-Aug-2019 / Accepted Date: 10-Sep-2019 / Published Date: 17-Sep-2019

Abstract

Objective: The potential for promoting nutrition and exercise to high school students is examined using brief duration educational videos. Teenage students routinely use and share internet videos for learning and leisure, but they could be a useful health tool. The purpose was to see if brief health videos will increase health behavior, concern or their interest in health, as measured by a self-assessment questionnaire of their weekly exercise and diet.

Methods: After a baseline health questionnaire, participants watched five brief health videos and then did repeat questionnaires 10 and 20 days later to assess for change.

Results: The data showed that students watching videos had a significant increase in concern about being healthy, and a perception of a benefit in their diet, exercise and interest in being healthier. However, a measurable change in their exercise and eating behavior as a result of the videos was not shown.

Conclusion: These findings suggest that brief health videos may be useful in promoting health awareness in high school students.

Keywords: Health video education; Health behavior; High school health; Prevention; Wellness

Introduction

Many studies describe a concerning level of unhealthy behavior in American teenagers which increases their risk for future disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2010 NYPANS (National Youth Physical Activity and Nutrition Study), is a high school age questionnaire detailing that obesity has tripled since 1980, and that 18% of 12-19-year-olds in the United States were obese [1]. A prevalence of sedentary behaviors and unhealthy diet, including regular consumption of fast food, fried potatoes, sugary drinks and pizza are described [2]. In the 2015 Health & Risk Behaviors of Massachusetts Youth Report, approximately 43% of adolescents spent 3+ hours a day playing video games or using the computer, 18% watched TV for 3+ hours on a school day, 12% ate vegetables 3+ times a day, and 61% had 1+ sweetened beverage a day, and 31% thought they were overweight [3].

Health intervention studies in teenagers have shown positive or mildly positive results with a variety of methods including support programs, school-based programs, medical clinics, and educational videos [4-10]. Questionnaire methods are commonly used by these youth studies to evaluate diet and exercise; however, studies were often limited to a short-term follow-up of a few weeks to 1 year. One review on obesity suggested that a 2-3-year follow-up is necessary to assess for a lasting effect and asked if the lack long-term success requires a different approach [11].

However, eating and exercise patterns alone do not provide a full assessment of health or weight concern. One study describes the complexity in assessing weight change among adolescents where approximately 61% of females and 21% of males were trying to lose weight, and 7% of females and 36% of males were trying to gain weight. Exercise was often used for losing weight among females and gaining weight among males [7]. Studies on youth motivations for healthy behavior have found several factors including intrinsic desire for health, self-worth and enjoyment of sports, as well as support or modeling from parents, peers and teachers [8,12-14]. A weak association between nutrition knowledge and eating behavior was found in one study of middle school students [15]. A time constraint was identified as another issue for healthy activity in one study on inactive adolescent females [14]. Although brief intervention studies in adolescents are more frequently done to assess behavior change in substance abuse [16], brief intervention to influence healthy behavior has been considered for the low cost and ease of use in medical clinics [17].

Methods

Five brief educational videos on healthy behavior, nutrition and exercise were chosen from the wide variety available on the internet. They were specifically chosen for having content with teenager level information, source reliability, subject relevance, and a combined total duration of approximately 20 minutes. Student questionnaires were adapted from the 2010 National Youth Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey. The questions used were health exercise and nutrition levels. Added questions were health concern and interest, and the postvideo perception of video effect on diet, exercise and health interest. Questionnaires were designed for brief answering, and videos chosen for brief duration to minimize participant drop-out.

Participants were randomly recruited from several local area high schools (grades 9-12) by handing out a brief, written explanation of the study. This was given to every student that said they were willing to read the explanation form. If they wanted to participate and supply an email for communication, they and their parent signed a permission form which includes an explanation of the experiment, confidentiality and information about potential risks, safety precautions, and stresses the importance of answering truthfully. The risk assessment explanation included: worrying about not being healthy, the health video information scaring them, being stressed out, and the possibility that their questionnaire information might not be confidential, exercise injury, heavy dieting, and weight loss. Participants were randomly placed in either the experimental group (31 participants) or the control group (6 participants) and the first questionnaire was sent via SurveyMonkey.com to their email. If no response was received within two days, two follow-up requests were sent asking them to answer the questionnaire. If the questionnaire was not returned, they were excluded from the experiment.

The five-video links were sent in a single email to all responding experimental participants (excluding the controls), asking them to reply when they have viewed the videos. They were asked to view all five videos at their own pace, but within a two-day period. 10-14 days later, all participants were asked to answer the second questionnaire. The same rules about the deadline and exclusion for the questionnaire was followed for the videos. The third and final questionnaire was sent after another 10-14 days.

The independent variable was whether the participants watched the health videos, which were delivered and measured by email communication to experimental and control groups. The dependent variables were recorded by email questionnaires via SurveyMonkey.com, before and at approximately 10 and 20 days after watching the videos. Variables included health behavior in eating salad or junk food, and exercise activity (amount in 0-7 days), and health concern, interest and perception of behavior change (1-5 scale, 1 being the least healthy/concern/interest, 5 being the healthiest/ concern/interest). Questionnaires were adapted from the 2010 National Youth Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey and email distributed with the SurveyMonkey.com website.

Pre-video, baseline questionnaire

Q1. During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day? (Add all time spent in physical activity that increased your heart rate and made you breathe hard some of the time.) (A: 0-7 days)

Q2. On how many of the past 7 days did you exercise or participate in physical activity for at least 20 minutes that made you sweat and breathe hard, such as basketball, soccer, running, swimming laps, fast bicycling, fast dancing? (A: 0-7 days)

Q3. During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat green salad? (A: 1-7)

1) I did not eat green salad during the past 7 days, 2) 1 to 3 times during the past 7 days,

3) 4 to 6 times during the past 7 days, 4.1 time per day 5) 2 times per day,

6) 3 times per day, 7) 4 or more times per day

Q4. During the past 7 days, on how many days did you eat at least one meal or snack from a fast food restaurant such as McDonald’s, Taco Bell, or KFC? (A: 0-7 days)

Q5. On a scale of 1 to 5, how concerned are you about being a healthy person?

(A: 1 being little or no concern, 5 being very concerned)

Q6. On a scale of 1 to 5, how healthy do you think you are currently?

(A: 1 being the least healthy, 5 being very healthy)

Demographic Questions

What high school do you go to? (A: GSMST, Parkview, Other) Gender?

(A: Male, Female)

Two post-video questionnaires #2 and #3 also included questions 7-9:

Q7. Do you think that the videos influenced your diet?

(A: 1 being a lot less healthy, 5 being a lot healthier)

Q8. Do you think the videos affected your exercise?

(A: 1 being a lot less exercise, 5 being a lot more exercise).

Q9. Do you think watching the videos made you more or less interested in being healthier?

(A: 1 being much less interested, 5 being much more interested)

Five health videos on YouTube

About 20 minutes in total (Videos were chosen from those available on YouTube using the search parameters: teenage, adolescent, high school student, nutrition, exercise, health behavior, should teens be healthy, why should you eat healthy, etc.).

1. Physical Activity Guidelines-Introduction by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (C.D.C. 2012), (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lEutFrar1dI)

2. HOW TO GET MOTIVATED when you don’t feel like WORKING OUT (Tony Horton Fitness 2014), (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hW7So0gjT4E)

3. Benefits of Eating Healthy (Healthy Choices 2016), (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qzztxZyOQh0)

4. You Are What You Eat-The Importance of Eating Healthy (Dr. Jason West 2017), (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bYnpFWs6F6w)

Teenage Nutrition! (Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen 2012), (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OgJ183CbGNI)

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Gwinnett School of Math, Science and Technology (GSMST) for study of human subjects. There were no incentives offered to individuals for completion of the surveys. Discrete and continuous variables were summarized by mean and standard deviation and categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and percentages. ANOVA and Chi square testing were used and described in the results. A p-value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25, Armonk, NY.

Results

Participant collection and dropout analysis

Initially about 60 students at the Gwinnett School of Math, Science and Technology (GSMST) were asked to participate. However, of the 60 students asked only 16 GSMST students agreed to participate and supply their email information. Therefore, an additional recruitment was done at Parkview High School and a few other local high schools to achieve a total of 31 experimental participants and 6 control participants that completed the first questionnaire. Of the initial 31 experimental subjects however, only 20 responded that they viewed the videos and were therefore given and completed the next two questionnaires. Thus, there were 11 dropouts from the initial experimental group. There was one dropout of the initial six questionnaire control group, resulting in five controls that completed all three questionnaires. Of the final 20 experimental and 5 control participants, all did complete the experiment and answer the three questionnaires with no additional dropouts or incomplete questionnaires.

Although there were 11 dropouts, there does not appear to be any obvious difference in the answers between the 31 initial respondents and the 20 respondents that stayed. For each of the six questions and two demographic questions, line graph comparisons were made to assess for possible bias by eyeball analysis. Each of the graphs appeared similar and therefore imply that the 11 dropouts were not different from the 20 used in the remainder of the experiment. There was an approximately equal number of participants for each gender and each high school.

Experimental group analysis

Exercise and Diet Behavior questions 1-4:

For the experimental group, there were no significant results to show an effect on health behavior after participants had viewed the videos. Questions 1 through 4, which ask about diet and exercise behavior throughout the past week, show no significant changes (Figure 1, Tables 1-3).

| Mean | Std. deviation | Std. error | 95% Confidence interval for mean | Minimum | Maximum | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||||

| Q1 | Before | 2.95 | 2.235 | 0.500 | 1.9 | 4 | 0 | 7 |

| 10 days after | 3.05 | 2.038 | 0.456 | 2.1 | 4 | 0 | 7 | |

| 20 days after | 3.05 | 1.701 | 0.38 | 2.25 | 3.85 | 1 | 7 | |

| Total | 3.02 | 1.97 | 0.254 | 2.51 | 3.53 | 0 | 7 | |

| Q2 | Before | 2.95 | 2.188 | 0.489 | 1.93 | 3.97 | 0 | 7 |

| 10 days after | 3.4 | 1.729 | 0.387 | 2.59 | 4.21 | 0 | 7 | |

| 20 days after | 3.6 | 1.759 | 0.393 | 2.78 | 4.42 | 1 | 7 | |

| Total | 3.32 | 1.891 | 0.244 | 2.83 | 3.81 | 0 | 7 | |

| Q4 | Before | 1.75 | 1.743 | 0.390 | 0.93 | 2.57 | 0 | 6 |

| 10 days after | 1.25 | 1.209 | 0.270 | 0.68 | 1.82 | 0 | 5 | |

| 20 days after | 1.05 | 1.276 | 0.285 | 0.45 | 1.65 | 0 | 5 | |

| Total | 1.35 | 1.436 | 0.185 | 0.98 | 1.72 | 0 | 6 | |

| Q5 | Before | 2.95 | 0.999 | 0.223 | 2.48 | 3.42 | 1 | 5 |

| 10 days after | 3.85 | 0.933 | 0.209 | 3.41 | 4.29 | 1 | 5 | |

| 20 days after | 3.7 | 1.031 | 0.231 | 3.22 | 4.18 | 1 | 5 | |

| Total | 3.5 | 1.05 | 0.136 | 3.23 | 3.77 | 1 | 5 | |

| Q6 | Before | 3.1 | 0.968 | 0.216 | 2.65 | 3.55 | 1 | 5 |

| 10 days after | 3.05 | 0.887 | 0.198 | 2.63 | 3.47 | 1 | 4 | |

| 20 days after | 3.15 | 0.875 | 0.196 | 2.74 | 3.56 | 1 | 4 | |

| Total | 3.1 | 0.896 | 0.116 | 2.87 | 3.33 | 1 | 5 | |

| Q7 | 10 days after | 3.85 | 0.745 | 0.167 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 3 | 5 |

| 20 days after | 3.8 | 0.616 | 0.138 | 3.51 | 4.09 | 3 | 5 | |

| Total | 3.83 | 0.675 | 0.107 | 3.61 | 4.04 | 3 | 5 | |

| Q8 | 10 days after | 3.55 | 0.686 | 0.153 | 3.23 | 3.87 | 2 | 5 |

| 20 days after | 3.7 | 0.657 | 0.147 | 3.39 | 4.01 | 3 | 5 | |

| Total | 3.63 | 0.667 | 0.106 | 3.41 | 3.84 | 2 | 5 | |

| Q9 | 10 days after | 4.35 | 0.813 | 0.182 | 3.97 | 4.73 | 2 | 5 |

| 20 days after | 4.2 | 0.696 | 0.156 | 3.87 | 4.53 | 3 | 5 | |

| Total | 4.28 | 0.751 | 0.119 | 4.03 | 4.52 | 2 | 5 | |

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for responses to questions measured in continuous scale.

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Between groups | 0.133 | 2 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.984 |

| within group | 228.850 | 57 | 4.015 | - | - | |

| Total | 228.983 | 59 | - | - | - | |

| Q2 | Between | 4.433 | 2 | 2.217 | 0.612 | 0.546 |

| within group | 206.550 | 57 | 3.624 | - | - | |

| Total | 210.983 | 59 | - | - | - | |

| Q4 | Between | 5.200 | 2 | 2.600 | 1.273 | 0.288 |

| within group | 116.450 | 57 | 2.043 | - | - | |

| Total | 121.650 | 59 | - | - | - | |

| Q5 | Between | 9.300 | 2 | 4.650 | 4.759 | 0.012 |

| within group | 55.700 | 57 | 0.977 | - | - | |

| Total | 65.000 | 59 | - | - | - | |

| Q6 | Between | 0.100 | 2 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.942 |

| within group | 47.300 | 57 | 0.83 | - | - | |

| Total | 47.400 | 59 | - | - | - | |

| Q7 | Between | 0.25 | 1 | 0.025 | 0.054 | 0.818 |

| within group | 17.750 | 38 | 0.467 | - | - | |

| Total | 17.775 | 39 | - | - | - | |

| Q8 | Between | 0.225 | 1 | 0.225 | -0.499 | 0.484 |

| within group | 17.150 | 38 | 0.451 | - | - | |

| Total | 17.375 | 369 | - | - | - | |

| Q9 | Between | 0.225 | 1 | 0.225 | 0.393 | 0.534 |

| within group | 21.750 | 38 | 0.572 | - | - | |

| Total | 21.975 | 39 | - | - | - | |

Table 2: ANOVA for testing difference in response between difference levels of exposure to videos.

| Q3 | Before | Video 10 days after | 20 days after | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I did not eat green salad during past 7 days | Count | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| % within video | 25.0% | 25.0% | 25.0% | 25.0% | |

| 1 to 3 times during the past 7 days | Count | 10 | 8 | 6 | 24 |

| % within video | 50.0% | 40.0% | 30.0% | 40.0% | |

| 4 to 6 times during the past 7 days | Count | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| % within video | 10.0% | 5.0% | 15.0% | 10.0% | |

| 1 time per day | Count | 2 | 5 | 5 | 12 |

| % within video | 10.0% | 25.0% | 25.0% | 20.0% | |

| 2 time per day | Count | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| % within video | 0.0% | 5.0% | 5.0% | 3.3% | |

| 4 or more times per day | Count | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| % within video | 5.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.7% | |

| Total | Count | 20 | 20 | 20 | 60 |

| % within video | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

Table 3: Descriptive statistics for responses to Q3.

For Q1, the mean difference for exercise 60 minutes=0.02 (C.I. 2.51-3.53).

For Q2, the mean difference for exercise 20 minutes=3.32 (C.I. 2.83-3.81).

For Q4, the mean difference for fast food diet=1.35 (C.I. 0.98-1.72). However, there was a non-significant trend on question 4 that showed that some participants did possibly start to eat less fast food as a result of watching the videos.

Data from questions 1, 2, and 4 were recorded as a continuous scale and the average responses were compared. The 95% confidence intervals for these questions overlapped, indicating no significant effect of the videos (Table 1, Figures 2-9). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the null hypothesis (Table 2). Only Q3 data is not answered a continuous scale (Table 3), so the chi square test was used on the data to test the different responses. The result =0.772, which shows no significant difference in response to the videos.

Health concern and interest questions 5-6

For Q5, which assessed the participants’ concern about their health, had a mean=3.50 (C.I. 3.23-3.77). It did show a statistically significant effect (p-value=0.012) of increased concern after viewing the videos (ANOVA Table 2). This was present on both post-video questionnaires. Multiple statistical comparisons between the 3 questionnaires using least significant differences show a significant difference in mean response of the pre-video with the mean response at 10 days and 20 days after videos (p-values 0.006 and 0.020 respectively, Table 4). There was no difference between the 10- and 20-day questionnaires. We can therefore reject the null hypothesis that concern for health is unchanged by watching the videos.

| (I) Video | (J) Video | Mean difference (I-J) | Std. error | Sig. | 95% Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Before | 10 days after | -.900* | 0.313 | 0.006 | -1.53 | -0.27 |

| 20days after | -0.75* | 0.313 | 0.2 | -1.38 | -0.12 | |

| 10 days after | Before | -900* | 0.313 | 0.006 | 0.27 | 1.53 |

| 20 days after | 0.150 | 0.313 | 0.633 | -0.48 | 0.78 | |

| 20 days after | Before | 0.750* | 0.313 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 1.38 |

| 10 days after | -.150 | 0.313 | 0.633 | -0.78 | 0.48 | |

Table 4: Multiple comparisons between groups for responses to Q5.

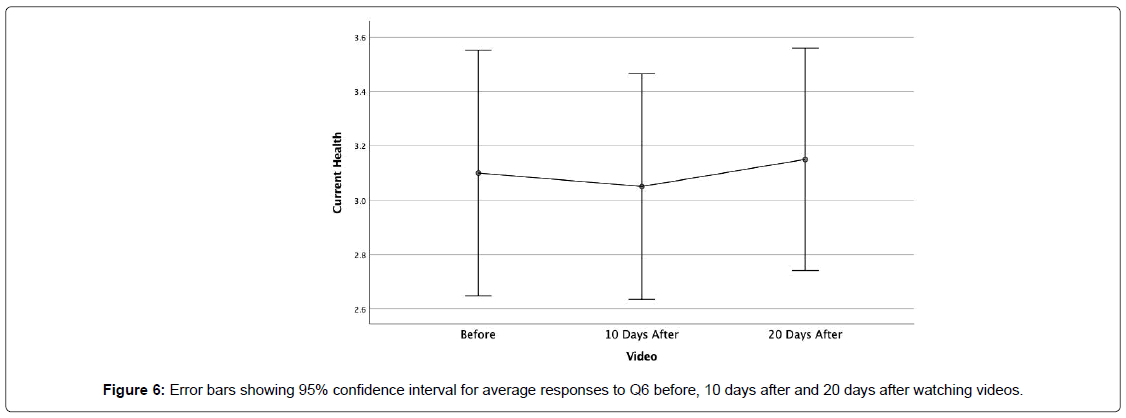

For Q6, which assessed how the participants perceive their current health, had a mean=3.10 (C.I. 2.87-3.33), and it showed no significant change (p=0.942, ANOVA Table 2).

Perception of video effect questions 7-9

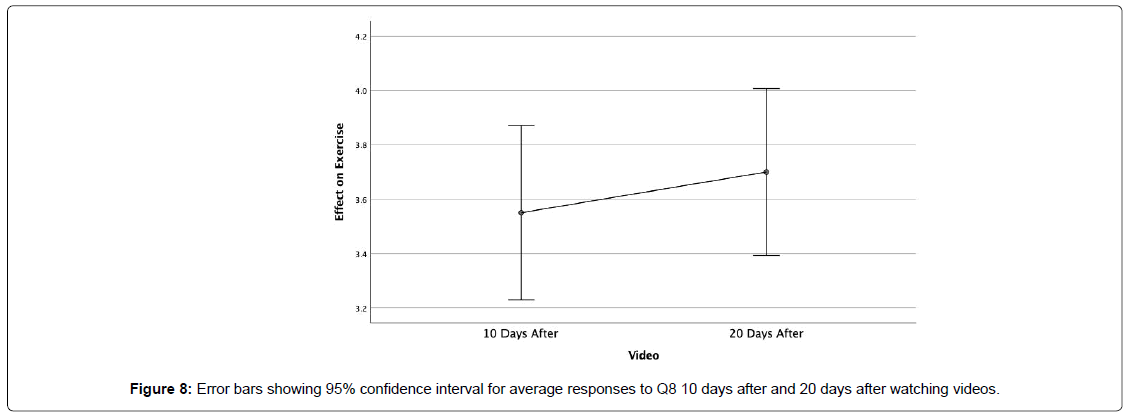

For Q7 - 9, which were only on the post-video questionnaires of the experimental group, participants were asked if they thought the videos improved their health activity, diet or interest. All three results showed a positive effect (Figures 7-9). Those that thought the videos had made their diet (Q7) a “little healthier” or a “lot healthier” included 65 and 70 % of the respondents in the second and third questionnaires, respectively. Those that thought the videos had made them exercise (Q8) a “little more” or a “lot more” included 55 and 60 % of the respondents in the second and third questionnaires, respectively. Those that thought the videos had made them more interested in being healthy (Q9) a “little more” or “a lot more” included 90 and 85 % of the respondents in the second and third questionnaires, respectively (Table 5).

| Question | 10 days after | 20 days after |

|---|---|---|

| Q7 Influenced diet | 65 | 70 |

| Q8 Affected exercise | 55 | 60 |

| Q9 Interest in health | 90 | 85 |

Table 5: Perceived benefit effect after videos.

The positive results persist in the second to the third questionnaire for each of questions 7-9, with no significant increase or decrease over the time between the questionnaires (p>0.05, ANOVA Table 2).

For the questionnaire control group, there is no significant difference in the answers to any the questions. Data was compered as an aggregate of the 20 student participants. An analysis of each individual student’s responses over time was not performed. The demographic questions, gender and school, show the sample had near equal representation in the experimental and the questionnaire control groups (Tables 6 and 7).

| Test Subject | Before video | 10 days after video | 20 days after video | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day? | ||||||

| Answer Choices | Responses | Responses | Responses | |||

| 0 days | 15.00% | 3 | 10.00% | 2 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 1 day | 20.00% | 4 | 10.00% | 2 | 10.00% | 2 |

| 2 days | 15.00% | 3 | 35.00% | 7 | 45.00% | 9 |

| 3 days | 10.00% | 2 | 5.00% | 1 | 15.00% | 3 |

| 4 days | 0.00% | 0 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 |

| 5 days | 30.00% | 6 | 25.00% | 5 | 15.00% | 3 |

| 6 days | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 |

| 7 days | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 |

| Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q2. On how many of the past 7 days did you exercise or participate in physical activity for at least 20 minutes? | ||||||

| 0 days | 15.00% | 3 | 5.00% | 1 | 0.00% | |

| 1 day | 15.00% | 3 | 0.00% | 0 | 15.00% | |

| 2 days | 20.00% | 4 | 35.00% | 7 | 15.00% | |

| 3 days | 10.00% | 2 | 15.00% | 3 | 20.00% | |

| 4 days | 10.00% | 2 | 15.00% | 3 | 10.00% | |

| 5 days | 15.00% | 3 | 20.00% | 4 | 30.00% | |

| 6 days | 10.00% | 2 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | |

| 7 days | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | |

| Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q3. During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat green salad? | ||||||

| I did not eat green salad during the past 7 days | 25.00% | 5 | 25.00% | 5 | 25.00% | 5 |

| 1 to 3 times during the past 7 days | 50.00% | 10 | 45.00% | 8 | 30.00% | 6 |

| 4 to 6 times during the past 7 days | 10.00% | 2 | 5.00% | 1 | 15.00% | 3 |

| 1 time per day | 10.00% | 2 | 25.00% | 5 | 25.00% | 5 |

| 2 times per day | 0.00% | 0 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 |

| 3 times per day | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 4 or more times per day | 5.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q4. During the past 7 days, on how many days did you eat at least one meal or snack from a fast food restaurant? | ||||||

| 0 days | 30.00% | 6 | 25.00% | 5 | 40.00% | 8 |

| 1 day | 20.00% | 4 | 45.00% | 9 | 35.00% | 7 |

| 2 days | 25.00% | 5 | 20.00% | 4 | 15.00% | 3 |

| 3 days | 10.00% | 2 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 |

| 4 days | 5.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 5 days | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 |

| 6 days | 5.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 7 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q5. On a scale of 1 to 5, how concerned are you about being a healthy person (1 being little or no concern, 5 being very concerned)? | ||||||

| 1 (little or no concern) | 10.00% | 2 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 |

| 2 | 15.00% | 3 | 0.00% | 0 | 5.00% | 1 |

| 3 (medium) | 50.00% | 10 | 20.00% | 4 | 25.00% | 5 |

| 4 | 20.00% | 4 | 55.00% | 11 | 45.00% | 6 |

| 5 (very concerned) | 5.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 4 | 20.00% | 4 |

| Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q6. On a scale of 1 to 5, how healthy do you think you are currently (1 being the least health, 5 being very healthy)? | ||||||

| 1 (least healthy) | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 | 5.00% | 1 |

| 2 | 20.00% | 4 | 20.00% | 4 | 15.00% | 3 |

| 3 (medium) | 40.00% | 8 | 40.00% | 8 | 40.00% | 8 |

| 4 | 30.00% | 6 | 35.00% | 7 | 40.00% | 8 |

| 5 (very healthy) | 5.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q7. Do you think that the videos influenced your diet? | ||||||

| 1 (a lot less healthy) | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | ||

| 2 (a little less healthy) | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | ||

| 3 ( no change) | 35.00% | 7 | 30.00% | 6 | ||

| 4 (l little healthier) | 45.00% | 9 | 60.00% | 12 | ||

| 5 (a lot healthier) | 20.00% | 4 | 10.00% | 0 | ||

| Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | |||

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |||

| Q8. Do you think the videos affected your exercise? | ||||||

| 1 (a lot less exercise) | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | ||

| 2 (a little less exercise | 5.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | ||

| 3 ( no change) | 40.00% | 8 | 40.00% | 8 | ||

| 4 (l little more exercise) | 50.00% | 10 | 50.00% | 10 | ||

| 5 (a lot more exercise) | 5.01% | 1 | 10.00% | 2 | ||

| Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | |||

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |||

| Q9. Do you think watching the videos made you more or less interested in being healthier? | ||||||

| 1 (much less interested) | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | ||

| 2 (a little less Interested) | 5.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | ||

| 3 ( no change) | 5.00% | 1 | 15.00% | 10 | ||

| 4 (l little more interested) | 40.00% | 8 | 50.00% | 3 | ||

| 5 (a lot more interested) | 50.01% | 10 | 35.00% | 7 | ||

| Answered | 20 | Answered | 20 | |||

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |||

| Q10. What high school do you go to? | ||||||

| Gwinnett school of Math, science and Tech | 30.00% | 6 | ||||

| Parkview | 35.00% | 7 | ||||

| other | 30.005 | 7 | ||||

| Answered | 20 | |||||

| skipped | 0 | |||||

| Q11. Gender | ||||||

| Female | 45.00% | 9 | ||||

| Male | 55.00% | 11 | ||||

| Answered | 20 | |||||

| skipped | 0 | |||||

Table 6: Experimental group-3 questionnaires.

| Test Subject | Before video | 10 days after video | 20 days after video | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. Past 7 days, how many were you physically active at least 60min/day? | ||||||

| Answer Choices | Responses | Responses | Responses | |||

| 0 days | 20.00% | 1 | 40.00% | 2 | 40.00% | 2 |

| 1 day | 20.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 20.00% | 1 |

| 2 days | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 3 days | 20.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 20.00% | 1 |

| 4 days | 20.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 5 days | 0.00% | 0 | 40.00% | 2 | 20.00% | 1 |

| 6 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 7 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q2. How many of the past 7 days did you exercise at least 20 min? | ||||||

| 0 days | 40.00% | 2 | 60.00% | 3 | 40.00% | 2 |

| 1 day | 40.00% | 2 | 0.00% | 0 | 40.00% | 2 |

| 2 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 3 days | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 |

| 4 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 5 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 6 days | 0.00% | 0 | 20.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 7 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q3. During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat green salad? | ||||||

| I did not eat green salad during the past 7 days | 40.00% | 2 | 20.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 1 to 3 times during the past 7 days | 40.00% | 2 | 40.00% | 2 | 40.00% | 2 |

| 4 to 6 times during the past 7 days | 20.00% | 1 | 40.00% | 2 | 20.00% | 1 |

| 1 time per day | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 40.00% | 2 |

| 2 times per day | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 3 times per day | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 4 or more times per day | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q4. During the past 7 days, on how many days did you eat at least one meal from a fast food restaurant? | ||||||

| 0 days | 40.00% | 2 | 40.00% | 2 | 20.00% | 1 |

| 1 day | 40.00% | 2 | 40.00% | 2 | 60.00% | 3 |

| 2 days | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 |

| 3 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 4 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 5 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 6 days | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 7 days | 0.00% | 5 | 0.00% | 5 | 0.00% | 0 |

| Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q5. On a scale of 1 to 5, how concerned are you about being a healthy person ? | ||||||

| 1 (little or no concern) | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 |

| 2 | 20.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 3 (medium) | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 |

| 4 | 20.00% | 1 | 60.00% | 3 | 60.00% | 3 |

| 5 (very concerned) | 20.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

| Q6. On a scale of 1 to 5, how healthy do you think you are currently ? | ||||||

| 1 (least healthy) | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 2 | 40.00% | 2 | 20.00% | 1 | 40.00% | 2 |

| 3 (medium) | 40.00% | 2 | 60.00% | 3 | 40.00% | 2 |

| 4 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 |

| 5 (very healthy) | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 | 20.00% | 1 |

| Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | Answered | 5 | |

| skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | skipped | 0 | |

Table 7: Questionnaire control group-3 questionnaires.

Discussion

This experiment is a randomized intervention trial with pre- and post-intervention testing of high-school students. Study subjects were randomized into an experimental group, that watched health education videos, and a questionnaire control group, that did not watch the videos.

For participants watching the health education videos, there was a statistically significant change in the participants’ concern for being a healthy person after watching the videos when comparing the pre and post video questionnaires. The level of significance with ANOVA was p=0.012. This significant effect was seen in both the second questionnaire, p=0.006, and third questionnaire, p=0.020. This experiment suggests that the participants had increased their concern about being healthy in response to the video information (question 5). Therefore, the null hypothesis of a concern about health being unchanged by watching health videos is rejected. It was less clear that there was any effect on actual behavior change being caused by watching the videos, with all testing of statistical significance being p>0.100 (questions 1-4). In this case the null hypothesis of a behavior change from watching health videos is not rejected. Because the sample size of the study was small, however, there may be minor effects on behavior that were not statistically significant.

There was no statistically significant change in the participants’ current perception of their level of health with p=0.060 (question 6). Perhaps watching health videos made students focus on their own diet and activity and did make some of them feel less healthy, while others may have felt good about their current health behavior. They may be a trend to healthy behavior in exercising more than 20 minutes (question #2) and eating less fast food (question #4) seen on the corresponding graphs, however this was not statistically significant, perhaps because the sample size was too small to detect an effect.

The three questions asking if participants thought that watching the videos influenced health behavior or health interest, all showed a positive effect in both post-video questionnaires (questions 7-9). However, these healthy perception answers were not supported by the corresponding behavior change answers (questions 1-4). This could possibly be explained by subtle changes that were not statistically significant due to the small sample size of the study. However, because these questions were specific (only about exercise, salad and junk food), they did not ask about other possible aspects of a healthy behavior change that may have occurred to explain the perception of healthier behavior. Perhaps participants had consumed less soda drinks, watched less television, or used stairs more often. A future questionnaire design could ask additional behavior change questions, ask less specific questions, or allow specific behavior change answers to be written in by the participants.

The positive results are supported by several studies that show a potential benefit in health behavior after an educational intervention [4-6,8,10]. However, these studies showed only minor changes in behavior and comment that health behavior change can be difficult. A true change in health behavior would presumably be less likely to occur than a change in thinking one is acting healthier. Therefore, a major change in behavior in the current study would not be expected to result after watching only 20 minutes of videos. Other investigators also suggest that newer technologies may be useful for facilitating health behavior interventions [6,9,18].

Although the results show an increase in concern and perception of healthy behavior, several limitations in this experiment need to be considered. Several potential sources of bias could have affected the experiment. There was possible selection bias when recruiting participants for the survey. To minimize selection bias students were randomly recruited to participate after reading an information consent form, and at multiple locations within GSMST as well as other schools. Having students from multiple schools would imply the results of this study may be more applicable to other local high school students.

The final data, however, was obtained from only 20 experimental participants and 5 questionnaire control participants that answered all three questionnaires. This low number of participants out of the total number of students asked to participate implies a potential bias in the type of students willing to participate. There are several potential reasons why recruitment and retention rates were low, however survey recruitment rates are often in the range of 25%, and the average email survey completion rate is 30% [19,20]. Retention of the participants in this study may have been helped by the study design. All potential students were told that the number of questions on the questionnaire and the length of the videos were very brief to encourage their participation. The experimental design of brief videos, quick questionnaires and completion in about one month was probably helpful in having no skipped questions and no additional participant dropouts after viewing the videos. The average time for each questionnaire completion in the study was about one minute. There were email reminders and thank-you notes for the post-intervention questionnaires to help with participant retention.

Recall bias in this study was minimized by using a short time frame for recall of the past 7-10 days of behavior. However, there were no skipped answers in this experiment probably because the questionnaires were designed to be brief and easy to complete in 1-2 minutes. Another potential information bias that may have happened would be if participants gave an answer that they believed the investigator wanted to hear, or to “help” the experiment, making the results less valid. Additionally, they may have either wanted the investigator to believe that they were healthy or may have answered like they wanted to believe they were healthy. During the experiment, many people answered that they thought the videos had improved their health, even though the results for the behavior change questions do not support this perception. The participants may have wanted to help the experiment, they might have had a false assumption that the videos did help, or they may have done something to improve their health that was not asked about in the questionnaire. However, the answers for question six, “how healthy do you think you are currently”, did not have a positive change, in either of the post-video questionnaires, and therefore do not suggest this type of bias toward “helping” the experiment.

Questions from the C.D.C.’s NYPANS questionnaire were used, but there were also added questions asking if the videos had increased the participants’ health interest. These were added because a significant change in actual behavior was not expected from briefly viewing videos, but that an increased health interest might result. Additional questions (#7, 8 and 9) asked participants if they thought the videos influenced their health interest or behavior. These were specifically worded to not be leading questions that might persuade people to answer one way (e.g. “How much do you think the videos affected your exercise?” instead of: “do you think the videos affected your exercise?” and offering them choices of negative or positive effect).

To account for these areas of bias more planning would be necessary in a future study. It would be advisable to recruit and retain more participants. Although information on gender and school was obtained, there were not enough participants to evaluate any association. The questionnaire control group was used to see if there was any effect on participant answers as a result of other variables (e.g. health related events or information during the timeframe of the three questionnaires, or impact of simply answering a health questionnaire). There did not appear to be any significant change in the answers in the questionnaire control group.

The health education videos used in this experiment were found though multiple internet searches. Despite the enormous number of health-related YouTube videos, there were surprisingly very few health education videos on YouTube that included the desired aspects of being factual, credible, short, relevant to the subject, motivating and appealing to teenagers. Many of the videos considered were lacking in these aspects, and none of the videos used had all these desired aspects. A future experiment could use a new video made for the purpose of the study, however they would be designed with the experimenter’s own bias toward health education issues.

From the positive results in this experiment other possibilities for future research could be considered. With a larger study size, a sub-group analysis could also be used to define what groups of teens the videos would be most effective on (e.g. gender, school, ethnicity, geographic region, body weight, athletic interest, etc.). One could also test different age ranges to see if the intervention influences other age groups. Extending the period of research to have additional questionnaires at 2 or 3 months may show if there is a longer lasting effect of the video intervention. Additional video education could be added for a longer duration than the 20 minutes to increase interest and/or understanding or repeated later, perhaps one month after the first viewing, to reinforce their health interest. However, this study was based on the desire to encourage healthier behavior by brief intervention that appeals to teenagers who might ignore longer duration video education. Finally, one could compare video to other forms of health education such as written or classroom information to determine what makes the most impact on people’s behavior.

High school students are often exposed to unhealthy influences on diet, drugs and other behaviors on the internet. Because teenagers frequently use the internet for information and leisure, and are interested in its evolving applications, it has great potential as a method of health education and deserves continued study. In addition, health prevention behavior and habits will have a greater impact on aging when begun early in life.

Conclusion

High school students in this study did show increased concern or perception about becoming healthier after watching brief educational videos. Although measurements of exercise and diet did not significantly change, the participants’ perception of a benefit from the videos was found and it persisted in the repeat questionnaire. If replicated with future studies, this suggests that health video education could be done with the intention of increasing student interest, concern or motivation, rather than expecting an actual change in behavior from only viewing brief videos. Additional methods would need to be added to accomplish improved behavior. Because teenage students routinely use the internet for their education and leisure, and frequently share interesting videos, brief health videos could become a useful tool. The current results could inspire health leaders to increase development of videos that are made to include aspects more relevant to teenage interest. Schools and medical offices could easily add this brief health video education method.

Because there are participants from more than one high school, the results may be more applicable to a larger population of teens. Although the study is limited by a small sample size, the data suggest that brief video education can increase concern and influence healthier behavior and interest. This research can potentially be used to help future disease prevention and health education efforts for high school students. Lowand middle-income communities and countries could also benefit from this affordable form of education. There is currently limited data on this area of research, but this could inspire further study and an emphasis on better health video design directed at high school students.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018) National youth physical activity and nutrition study (NYPANS). Adolescent and School Health.

- Brener N D, Eaton DK, Kann LK, McManus TS, Lee SM, et al. (2013) Behaviors related to physical activity and nutrition among U.S. high school students. J Adolesc Health 53: 539-546.

- Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (2015) Health & risk behaviors of Massachusetts youth.

- Bayne-Smith M, Fardy PS, Azzollini A, Magel J, Schmitz KH, et al. (2004) Improvements in heart health behaviors and reduction in coronary artery disease risk factors in urban teenaged girls through a school-based intervention: The PATH program. Am J Public Health 94: 1538-1543.

- Fardy PS, White RE, Clark LT, Amodio G, Hurster MH, et al. (1995) Health promotion in minority adolescents: A healthy people 2000 pilot study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 15: 65-72.

- Long JD, Stevens KR (2004) Using technology to promote selfâ€efficacy for healthy eating in adolescents. J Nurs Scholarsh 36: 134-1398.

- Middleman AB, Vazquez I, Durant RH (1998) Eating patterns, physical activity, and attempts to change weight among adolescents. J Adolesc Health 22: 37-42.

- De Meester F, van Lenthe FJ, Spittaels H, Lien N, De Bourdeaudhuij I (2009) Interventions for promoting physical activity among European teenagers: A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 6: 82.

- Pugh G, Gravestock HL, Hough RE, King WM, Wardle J, et al. (2016) Health behavior change interventions for teenage and young adult cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 5: 91-105.

- Walker Z, Townsend J, Oakley L, Donovan C, Smith H, et al. (2002) Health promotion for adolescents in primary care: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ 325: 524.

- Kilpatrick M (2005) College students’ motivation for physical activity: Differentiating men’s and women’s motives for sport participation and exercise. J Ame Colleg Health 54: 87-94.

- Lau R, Quadrel M, Hartman K (1990) Development and change of young adults’ preventive health beliefs and behavior: Influence from parents and peers. J Health Soc Behav 31: 240-259.

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Tharp T, Rex J (2003) Factors associated with changes in physical activity. JAMA 157: 803-810.

- Pirouznia M (2001) The association between nutrition knowledge and eating behavior in male and female adolescents in the US. Int J Food Sci Nutritn 52: 127-132.

- Winters KC (2016) Brief interventions for adolescents. J drug Abuse 2: 1.

- Olson AL, Gaffney CA, Lee PW, Starr P (2008) Changing adolescent health behaviors: The healthy teens counseling approach. Ame J Prevent Med 35: 359-364.

- Young MM (2010) Twitter me: Using micro-blogging to motivate teenagers to exercise. Inte Conference Design Sci Res Informat Systems. In: Winter R, Zhao JL, Aier S (eds) Global Perspectives on Design Science Research. DESRIST 2010. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 6105. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Citation: Rasler LF (2019) The Effect of Brief Health Education Videos on High School Students. J Community Med Health Educ 9:666.

Copyright: © 2019 Rasler LF. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 2675

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Apr 07, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1926

- PDF downloads: 749