The Down Syndrome-Associated Protein, Regulator of Calcineurin-1, is Altered in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Received: 21-Jan-2019 / Accepted Date: 27-Feb-2019 / Published Date: 06-Mar-2019 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0460.1000462

Abstract

There is a known relationship between Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Down syndrome (DS), with the latter typically developing AD-like neuropathology in mid-life. In order to further understand this relationship we examined intersectin-1 (ITSN1) and the regulator of calcineurin-1 (RCAN1), proteins involved in endosomal and lysosomal trafficking that are over-expressed in DS. We examined RCAN1 and ITSN1 levels (both long (-L) and short (-S) isoforms) and the level of endogenous metals in White Blood Cells (WBCs) collected from AD patients who were enrolled in the Australian Imaging, Biomarker and Lifestyle Study on Ageing (AIBL). We also examined RCAN1 and ITSN1-S and -L in post-mortem brain tissue in a separate cohort of patients with AD or other types of dementia including Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) and non-Alzheimer’s disease dementia. We found that RCAN1 was significantly elevated in AD and DLB brain compared with controls, but there was no difference in the level of RCAN1 in WBCs of AD patients. There were no differences in the levels of ITSN1-L and –S between AD and the control, nor between other types of dementia and the control. We found that there were no differences in the levels of metals between AD and the control WBCs. In conclusion, our data demonstrate that RCAN1 is differentially regulated between the peripheral and central compartments in AD and should be further investigated to understand its potential role in dementia of AD and DLB.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease; Down syndrome; Dementia

Introduction

The current worldwide incidence of dementia is believed to be fifty million people, and this number is expected to reach 75 million in 2030 if no cure is found (Alzheimer’s disease international, 2017) [1]. Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, is characterised by neuropathological changes (including the development of β−amyloid plaques (Αβ), Neurofibrillary Tangles (NFTs) and other anatomical features that spread throughout the brain) that result in a variety of clinical symptoms including short-term and long-term memory loss, confusion, depression and language problems. Ultimately, patients can become severely demented, lose ambulation and are reduced to a behavioural repertoire consisting of a few basic reflexes [2,3]. The individual neuropathological features of the AD brain are not unique to this disease, and are found across a spectrum of disorders and species [4]. One such example is Down Syndrome (DS), where individuals develop Αβ neuriticplaques, tau-containing NFTs [5], Basal Forebrain Cholinergic Neurodegeneration (BFCN) and enlarged early endosomes. These features may be the result of an over-expression of multiple genes or an alteration in key proteins or discrete cellular pathways. It has also been suggested, however, that another shared pathology, enlarged early endosomes, may contribute to pathological processes in both AD and DS and may be mediated through common pathways. Two genes involved in endocytosis, both located on chromosome 21, are intersectin-1 (ITSN1) and the regulator of calcineurin-1 (RCAN1, formerly called Down syndrome candidate region 1) [6-9]. This is relevant because DS is characterised by a triplication of chromosome 21, which is also the location of the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) gene that ultimately gives rise to the Αβ protein that forms the plaques found in AD and DS.

Through endocytosis, neurons achieve the rapid vesicle recycling necessary for maintaining neurotransmission but endocytosis is also the process used by neurons and other cell types to take up macromolecules from the extracellular environment. Early endosomes receive extracellular molecules from the cell surface via fusion with clathrincoated vesicles. Disrupted endocytosis has been postulated to result in abnormal uptake and trafficking through signalling endosomes of vital plasma membrane proteins, growth factors and receptors [10]. Early endosomes are the sites of internalisation of APP and apolipoprotein E, as well as the site of Aβ peptide generation, all of which contribute to the manifestation of AD [11]. In addition, defective neuronal growth factor signaling due to disturbances in endocytosis could be an early event in the manifestation of AD [12] which can lead to the formation of amyloid plaques, hyperphosphorylated tau and NFTs and BFCN [13]. In DS, enlarged endosomes are seen as early as 28 weeks of gestation in neurons [10], which precedes diffuse Aβ plaque deposition which appears at around 12 years of age, and is followed by mature Aβ plaques when the individuals are in their 30s [14]. In 2008 the genes associated with cognitive decline in the brains of aging individuals with AD were identified by profiling RNA expression of the whole genome in the frontal cortex and comparing them to their matched controls. Of relevance to this study, amongst the RNA transcripts significantly up-regulated in AD was the short isoform of intersectin-1 (ITSN1-S) [15]. Although this study reported that ITSN1 is overexpressed in the AD brain [15], there is nothing in the literature about the expression of ITSN1 at the protein level or in other types of dementia. It is of note, however, that ITSN1 protein levels have been examined in DS individuals that had concomitant AD pathology [16]. This study showed that DS individuals with AD pathology have a higher level of expression of ITSN1 in their frontal cortex compared with healthy controls, but interestingly DS individuals with diagnosis of AD had lower levels of both ITSN1-S and -L compared to DS without an AD diagnosis [16]. Similarly, previous studies have shown that the level of RCAN1 mRNA was increased in the AD brain [17,18] and that the level of RCAN1 protein was increased in the pyramidal neurons of the AD temporal lobe [19], but there is almost nothing in the literature about the levels of RCAN1in other types of dementia. Ermak et al. [17] also showed that amyloid β1-42 stimulates production of RCAN1 mRNA in a cell culture model. Furthermore, Lloret et al. [20] showed that in a primary rat neuronal cell culture model in the presence of amyloid β, tau phosphorylation increased but silencing RCAN1 in these neurons blocked the hyperphosphorylation of tau indicating that RCAN1 has a role in tau phosphorylation.

For these reasons, we hypothesised that protein levels of both ITSN1 and regulator of calcineurin-1 RCAN1 would be altered in AD brain tissues, and may also be altered in related conditions, including Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and non-Alzheimer’s disease dementia (non-AD; including corticobasal degeneration and supranuclear palsy). Changes in these proteins may implicate endocytic and lysosomal trafficking deficits across a broad suite of neurodegenerative diseases.

As our targets of interest have been found in various tissues throughout the body [21], we were also interested in determining whether or not they were changed in the periphery, as this might represent a potential biomarker [22,23] or provide some insight into the pathogenesis of disease. For these analyses we were fortunate to have access to white blood cells, which are a critical component of the peripheral compartment and may be involved either directly or indirectly in the pathogenesis of a variety of conditions including AD [24,25], from both healthy controls and AD patients from the Australian imaging, Biomarker and Lifestyle Study of Ageing (AIBL). Furthermore, both ITSN1 and RCAN1 are involved in transporting material inside and outside the cell; RCAN1 regulates vesicle exocytosis [26] and ITSN1-L isoform regulates the amount of secretory vesicle exocytosis and synaptic vesicle endocytosis [9]. Therefore, it is possible that they would be involved in the transportation of metals, which are reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of a variety of neurodegenerative diseases (such as AD). ITSN1 is also involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis, and it is reported to impact the internalization of the transferrin receptor, which is crucially involved in cellular iron regulation [27]. Hence, we hypothesised that if the level of ITSN1 and RCAN1 were altered in the periphery, then this may also translate to a change in metal levels. Hence, we assessed both protein (ITSN1 and RCAN1) and metal (including major elements such as coppr, zinc, iron and calcium) content in the white blood cells.

Materials and Methods

Human brain tissue

Human post-mortem brain tissues used in this project were provided by the Victorian Brain Bank Network and the University of California Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (UCI-ADRC) and the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders. The demographics of these cases are listed in Table 1. Samples included frontal and temporal cortices from controls with no neurological disorders (average e± SD; 80.8 ± 14.5 years of age), AD (78.3 ± 9.1 years of age), non-AD (including corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy cases; 77.7 ± 6.9 years of age), and DLB (82.6 ± 7.3 years of age) patients. There was no statistical difference in the average age of each of these cohorts. The average Post Mortem Interval (PMI) for the tissues were as follows; controls (22.1 ± 27.7 hours), AD (33.4 ± 22 hours), non-AD (28.6 ± 16.3 hours) and DLB (41.8 ± 22.7 hours). The variation in PMI is similarly large across all the groups, and there was no statistically significant difference between groups. The tissues were stored at -80˚C until required.

Human blood samples

White blood cell samples from fasting AD (n=50, 77.5±11.5 years of age) and age-matched healthy controls (n=20, 79 ± 10 years of age) were obtained from AIBL.

Western blotting of human samples

Western blotting was used to quantify the relative levels of RCAN1, ITSN1 long and ITSN1 short isoforms in both human brain and white blood cell samples. Specific cohort sizes are shown in the figures. Postmortem tissue was weighed and homogenized in 4x the volume in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) containing 0.1% SDS and 0.1% Triton-100, supplemented with proteinase inhibitor tablets (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). White blood cell samples were homogenised in dH2O containing 0.1% SDS and 0.1% Triton-100, supplemented with proteinase inhibitor tablets (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Mannheim,Germany). Each sample was sonicated for 10 cycles of 10 seconds on and 10 seconds off. Further, the samples were spun for 10 mins and the soluble phase collected for experiment. Protein concentrations of all the samples were initially quantified using a bicinchoninic (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce, Thermo scientific, Rockford, USA) so that equal protein concentrations (40 μg) of each homogenised sample could be loaded per lane and subsequently resolved on 3-8% Criterion XT Tris-Acetate pre-cast gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using XT Tricine running buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). This was followed by electroblotting onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P) using transfer buffer containing 5% methanol.

Membranes were incubated in milk (5%w/v) followed by applying the primary rabbit anti-ITSN1 (1:750) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) in blocking buffer (5% w/v fat-free milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, pH 8.0) and anti RCAN-1 (1:1000; MorphoSys AG, Planegg, Germany) in signal boost solution 1 buffer (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) and incubated overnight at 4oC.

Immunoreactive proteins were detected using HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse (1:2000; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) in blocking buffer (5% w/v fat-free milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, pH 8.0) or HRP-conjugated goat anti human (1:2000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Baltimore, USA) in signal boost solution buffer 2, respectively. ITSN1 membranes were incubated with Amersham ECL western blotting detection reagent and RCAN1 was visualized using Luminata Forte western HRP substrate (Millipore, Burlington, USA). Images of the western blots were taken using an ImageReader LAS- 3000 (FujiFilm, Tokyo, Japan) and the abundance of proteins quantified (density of bands at the given molecular weight) using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare, Fairfield, USA). The data are then presented as relative band intensity.

Metal analysis by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

Due to our long standing interest in the role of metals in the pathogenesis of AD, we assessed metal levels in the white blood cells from both AD and healthy control patients. Whilst this in of itself is interesting, to determine whether there was any potential involvement of ITSN1 and RCAN1 in metal homeostasis in the periphery (which may reflect central metal changes), then we correlated the protein and metal levels. We utilized Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICPMS) as described previously [28]. Triplicates of each sample were measured.

Statistical analysis

Data for human tissue are presented as box and whiskers for comparison of AD and controls, and were compared using a two-tailed student’s t-test. Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as means ± SEM for other types of dementia and controls, and were compared by one way ANOVA with Dunnet’s post-hoc test. Data for WBCs metals were analysed using a two-tailed student’s t-test. A Pearson’s two-tailed correlation test was used to test the correlation between proteins and metals. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). On all the figures, the significance is denoted by the following: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001.

Results

Intersectin-1 protein levels are unchanged in brain tissue in various neurological diseases

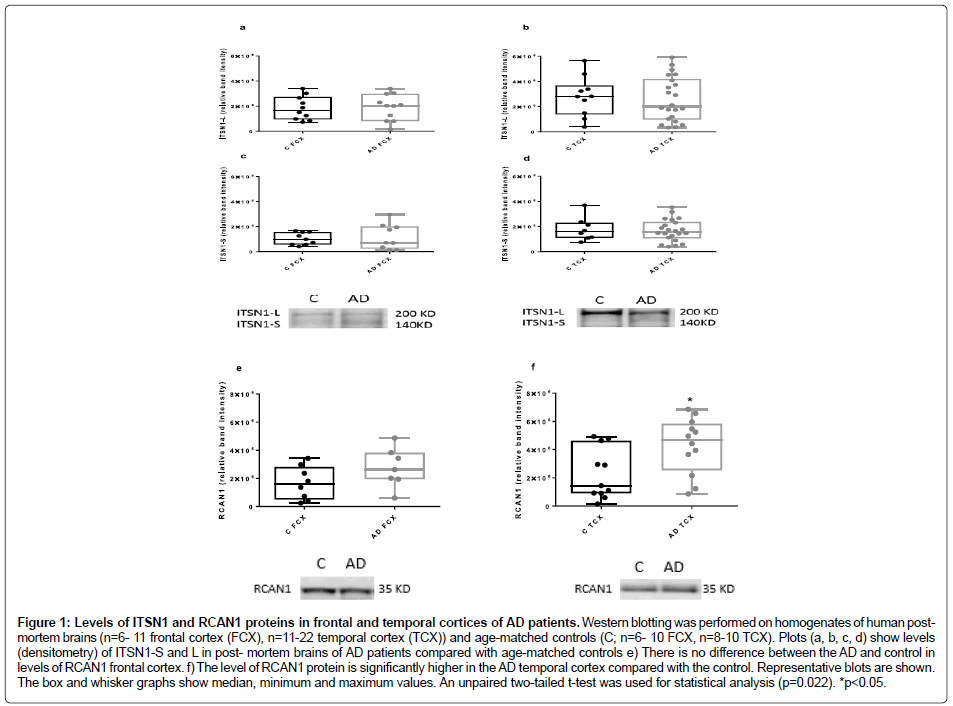

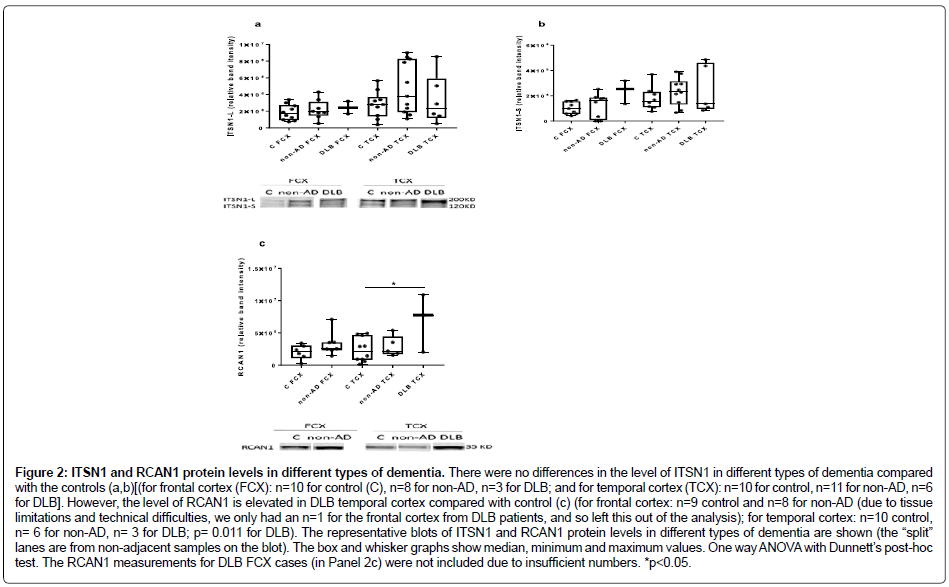

There were no differences between the levels of ITSN1 proteins in frontal and temporal cortices of AD patients compared with the controls (unpaired two-tailed t-test; n=6-10 for control frontal cortex and n=6-12 for AD frontal cortex; n =8-10 control temporal cortex, n=11-22 for AD temporal cortex (Figure 1a-1d). Similarly, there were no differences between other types of dementia and the controls (one way ANOVA with Dunnet’s post-hoc test; Figure 2a and Figure 2b).

Figure 1: Levels of ITSN1 and RCAN1 proteins in frontal and temporal cortices of AD patients. Western blotting was performed on homogenates of human postmortem brains (n=6- 11 frontal cortex (FCX), n=11-22 temporal cortex (TCX)) and age-matched controls (C; n=6- 10 FCX, n=8-10 TCX). Plots (a, b, c, d) show levels (densitometry) of ITSN1-S and L in post- mortem brains of AD patients compared with age-matched controls e) There is no difference between the AD and control in levels of RCAN1 frontal cortex. f) The level of RCAN1 protein is significantly higher in the AD temporal cortex compared with the control. Representative blots are shown. The box and whisker graphs show median, minimum and maximum values. An unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for statistical analysis (p=0.022). *p<0.05.

Figure 2: ITSN1 and RCAN1 protein levels in different types of dementia. There were no differences in the level of ITSN1 in different types of dementia compared with the controls (a,b)[(for frontal cortex (FCX): n=10 for control (C), n=8 for non-AD, n=3 for DLB; and for temporal cortex (TCX): n=10 for control, n=11 for non-AD, n=6 for DLB]. However, the level of RCAN1 is elevated in DLB temporal cortex compared with control (c) (for frontal cortex: n=9 control and n=8 for non-AD (due to tissue limitations and technical difficulties, we only had an n=1 for the frontal cortex from DLB patients, and so left this out of the analysis); for temporal cortex: n=10 control, n= 6 for non-AD, n= 3 for DLB; p= 0.011 for DLB). The representative blots of ITSN1 and RCAN1 protein levels in different types of dementia are shown (the “split” lanes are from non-adjacent samples on the blot). The box and whisker graphs show median, minimum and maximum values. One way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test. The RCAN1 measurements for DLB FCX cases (in Panel 2c) were not included due to insufficient numbers. *p<0.05.

RCAN1 levels are elevated in the temporal cortex in AD and DLB

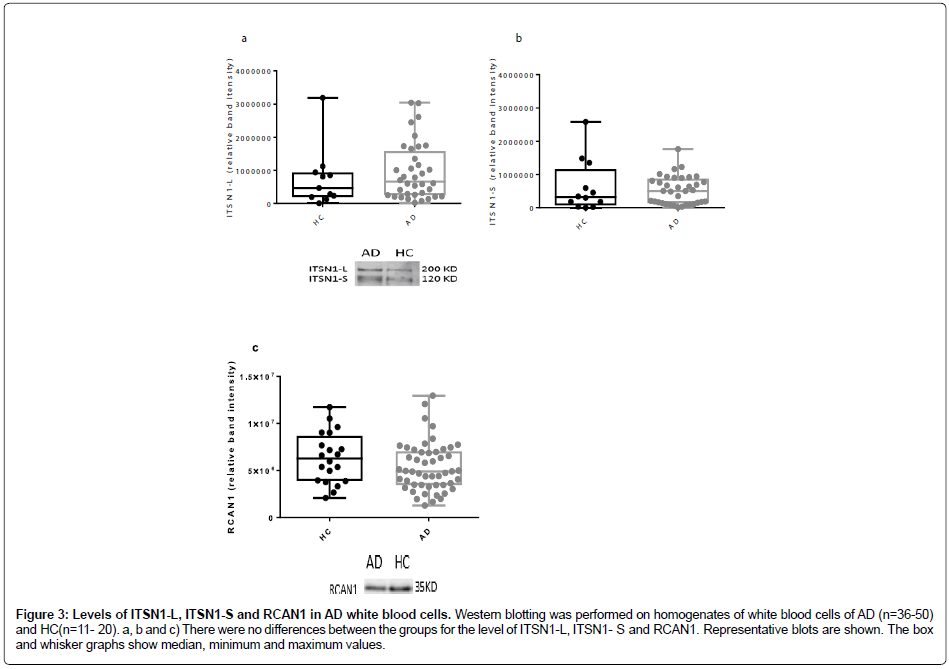

Assessment of RCAN1 levels in frontal and temporal cortices from our cohort of neurological diseases (Figure 1e, Figure 1f and Figure 2c) revealed a significant elevation only in the temporal cortex of both AD and DLB tissue, as compared to controls (Figure 1f and Figure 2c). There were no other differences noted. Intersectin-1 and RCAN1 protein levels in white blood cells in AD. The protein levels of both the short and long isoforms of ITSN1 (Figure 3a and Figure 3b), as well as RCAN1 (Figure 3c) were no different between the AD and healthy controls.

Figure 3: Levels of ITSN1-L, ITSN1-S and RCAN1 in AD white blood cells. Western blotting was performed on homogenates of white blood cells of AD (n=36-50) and HC (n=11- 20). a, b and c) There were no differences between the groups for the level of ITSN1-L, ITSN1- S and RCAN1. Representative blots are shown. The box and whisker graphs show median, minimum and maximum values.

Metal analysis in white blood cells, and correlation with RCAN1 and ITSN1

There were no differences in the levels of any metals measured (iron, zinc, copper, calcium, magnesium, manganese, aluminium, lead or selenium) between the AD and the control white blood cells (Table 2). We also examined whether there was a correlation between the level of the proteins of interest (RCAN1 or ITSN1) and the level of each metal across our two cohorts using a Pearson’s two-tailed correlation. There was no correlation between the levels of any of the proteins and metals (Table 2).

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that there are elevated levels of RCAN1 protein in both AD and DLB temporal cortices, as compared to matched controls. These findings are consistent with a previous study conducted in AD patients, where it was shown that RCAN1 mRNA was elevated (~ two fold) in the cerebral cortex (areas A10 and A22) and hippocampus, but not the cerebellum, of AD patients [17]. This study also demonstrated an association with NFTs, such that RCAN1 mRNA was significantly higher in patients with extensive NFTs (~ three fold). In a cell culture system, it was also shown that amyloid β1-42 increases RCAN1 mRNA [17]. This current study, therefore, extends on the previous work that only examined changes in RCAN1 mRNA, to demonstrate that this is likely to also translate to protein level changes in AD. That RCAN1 was also altered in DLB may speak to converging pathways in DLB and AD. Studies such as Lippa et al. [29] have also shown the presence of Lewy bodies in many Down syndrome brains with AD. Further studies are required to investigate the relevance of RCAN1 in AD, and to also interrogate the potential role/interaction of RCAN1 in the context of neurological diseases such as DLB. We did not observe any differences in RCAN1 levels in WBCs of AD and healthy controls, which may suggest that changes in the level of RCAN1 in the post-mortem brain might be locally/differently regulated compared with peripheral RCAN1 levels. As with the post-mortem brain studies, the AD brain may contribute to the disease evolution and progression. Although our results did not show a significant change in the levels of ITSN1 in the AD brain or the other types of dementia, statistical power analysis revealed that if the number of samples was increased to 35 or more per group, the result might reach statistical significance (this would also potentially help overcome issues around varying PMI times and the limited “snapshot” that comes from analysing individuals from an isolated age range). That our current data are in conflict with an existing report suggesting that ITSN1 levels are elevated in AD, this previous study assessed RNA levels only, whereas we assessed protein levels in the current body of work. As such, it is possible that there is disconnect between the RNA and protein regulation/levels for ITSN1, or perhaps there was a cohort-specific difference between studies that would account for this difference. One consideration is the PMI, which could impact protein measurements. A few minutes after death, autolysis occurs resulting in the release of water and enzymes which degrade proteins, carbohydrates and lipids [30]. Environmental factors such as temperature and humidity would also affect the rate of decomposition. For this reason, it is hard to predict how the PMI by itself has affected the protein content of the samples [16]. Similarly, it is not possible to predict in what way our data for levels of ITSN1 protein in dementia brains would have been affected. Nevertheless, the samples with the longer PMI times would likely have had more protein decomposition than the samples with the shorter PMI, which could have affected the level of ITSN1 measured in the samples (whilst there were no significant differences in the PMI between cohorts in the current study, there was a trend for the healthy control group to have shorter PMI times than all other groups). Obtaining better controlled autopsy samples would help mitigate some of these issues. Another issue to consider is whether the presence of significant systemic disease in our sample population might have influenced the outcomes of the current studies, as there were individuals that had sepsis and renal failure amongst other comorbidities [31]. Given the reported role of ITSN1 in a breadth of cellular pathways, then this remains an important caveat of our work.

Conclusion

There is a potential point of intersection between the neuropathology/ disease pathogenesis present in DS and other neurological diseases such as AD and DLB that centers around the regulation of RCAN1 and potentially the associated endocytic pathways. Further investigation is required to understand the relevance of this protein and pathways to disease.

Acknowledgements

The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health acknowledge the strong support from the Victorian Government and in particular the funding from the Operational Infrastructure Support Grant. The UCI-ADRC is funded by NIH/NIA Grant P50 AG16573. NM was supported by a NHMRC Dora Lush PhD scholarship.

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, et al. (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 34: 939-939.

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, et al. (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the national institute on aging-alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia 7: 263-269.

- Adlard PA, Cummings BJ (2004) Alzheimer’s disease--asum greater than its parts? Neurobiol Aging 25: 725-733.

- Mann D (1988) The pathological association between Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Mech Ageing Dev 43: 99-136.

- Keating DJ, Chen C, Pritchard MA (2006) Alzheimer's disease and endocytic dysfunction: Clues from the Down syndrome-related proteins, DSCR1 and ITSN1. Ageing Res Rev 5: 388-401.

- Pechstein A, Shupliakov O, Haucke V (2010) Intersectin 1: A versatile actor in the synaptic vesicle cycle. Biochem Soc Trans 38: 181-186.

- Tsyba L, Nikolaienko O, Dergai O, Dergai M, Novokhatska O, et al. (2011) Intersectin multidomain adaptor proteins: Regulation of functional diversity. Gene 473: 67-75.

- Yu Y, Chu P, Bowser DN, Keating DJ, Dubach D, et al. (2008) Mice deficient for the chromosome 21 ortholog Itsn1 exhibit vesicle-trafficking abnormalities. Hum Mol Genet 17: 3281-3290.

- Cataldo AM, Peterhoff C., Troncoso JC, Gomez-Isla T, Hyman BT, et al. (2000) Endocytic pathway abnormalities precede amyloid β deposition in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome: Differential effects of APOE genotype and presenilin mutations. Am J Pathol 157: 277-286.

- Nixon RA (2005) Endosome function and dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Aging 26: 373-382.

- Salehi A, Delcroix JD, Mobley WC (2003) Traffic at the intersection of neurotrophic factor signaling and neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci 26: 73-80.

- Capsoni S, Ugolini G, Comparini A, Ruberti F, Berardi N, et al. (2000) Alzheimer-like neurodegeneration in aged antinerve growth factor transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 6826-6831.

- Lemere C, Blusztajn J, Yamaguchi H, Wisniewski T, Saido T, et al. (1996) Sequence of deposition of heterogeneous amyloid β-peptides and APO E in Down syndrome: Implications for initial events in amyloid plaque formation. Neurobiol Dis 3: 16-32.

- Wilmot B, McWeeney SK, Nixon RR, Montine TJ, Laut J, et al. (2008) Translational gene mapping of cognitive decline. Neurobiol Aging 29: 524-541.

- Hunter MP, Nelson M, Kurzer M, Wang X, Kryscio RJ, et al. (2011) Intersectin 1 contributes to phenotypes in vivo: Implications for Down Syndrome. Neuroreport 22: 767-772.

- Ermak G, Morgan TE, Davies KJ (2001) Chronic overexpression of the calcineurin inhibitory gene DSCR1 (Adapt78) is associated with Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem 276: 38787-38794.

- Harris CD, Ermak G, Davies KJ (2007) RCAN1-1L is overexpressed in neurons of Alzheimer's disease patients. FEBS J 274: 1715-1724.

- Cook CN, Hejna MJ, Magnuson DJ, Lee JM (2005) Expression of calcipressin1, an inhibitor of the phosphatase calcineurin, is altered with aging and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 8: 63-73.

- Lloret A, Badia MC, Giraldo E, Ermak G, Alonso MD, et al. (2011) Amyloid-β toxicity and tau hyperphosphorylation are linked via RCAN1 in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 27: 701-709.

- Fuentes JJ, Pritchard MA, Estivill X (1997) Genomic organization, alternative splicing, and expression patterns of the DSCR1 (Down syndrome candidate region 1) gene. Genomics 44: 358-361.

- Carmona P, Molina M, Calero M, Bermejo-Pareja F, Martinez-Martin P, et al. (2012) Infrared spectroscopic analysis of mononuclear leukocvytes in peripheral blood from Alzheimer's disease patients. Anal Bioanal Chem 402: 2015-2021.

- Shad K, Aghazadeh Y, Ahmad S, Kress B (2013) Peripheral markers of Alzheimer's disease: Surveillance of white blood cells. Synapse 67: 541-543.

- Chen SH, Bu XL, Jin WS, Shen LL, Wang YJ, et al. (2017) Altered peripheral profile of blood cells in Alzheimer disease. Medicine 96: e6843.

- De Luca C, Colangelo AM, Alberghina L, Papa M (2018) Neuro-immune hemostasis: Homeostasis and diseases in the central nervous system. Front Cell Neurosci 12: 459.

- Keating DJ, Dubach D, Zanin MP, Yu Y, Martin K, et al. (2008) DSCR1/RCAN1 regulates vesicle exocytosis and fusion pore kinetics: Implications for Down syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet 17: 1020-1030.

- Thomas S, Ritter B, Verbich D, Sanson C, Bourbonnière L, et al. (2009) Intersectin regulates dendritic spine development and somatodendritic endocytosis but not synaptic vesicle recycling in hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem 284: 12410-12419.

- Adlard PA, Cherny RA, Finkelstein DI, Gautier E, Robb E, et al. (2008) Rapid restoration of cognition in Alzheimer's transgenic mice with 8-hydroxy quinoline analogs is associated with decreased interstitial Aβ. Neuron 59: 43-55.

- Lippa CF, Schmidt ML, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ (1999) Antibodies to α-synuclein detect Lewy bodies in many Down's syndrome brains with Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 45: 353-357.

Citation: Malakooti N, AIBL Research Group, Fowler C, Volitakis I, McLean CA, et al. (2019) The Down Syndrome-Associated Protein, Regulator of Calcineurin-1, is Altered in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 9: 462. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0460.1000462

Copyright: © 2019 Malakooti N, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.