Research Article Open Access

The Dietitians Role in Palliative Care: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Scope and Emerging Competencies for Dietitians in Palliative Care

Pinto IF1*, Pereira JL2, Campos CJ1 and Thompson JL3

1University of Campinas, School of Nursing, Campinas, Brazil

2Division of Palliative Care, Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa Medical Chief, Palliative Medicine, Bruyère Continuing Care, Ottawa, Canada

3University of Birmingham, School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, Birmingham, UK

- *Corresponding Author:

- Isabel Luísa Gomes Ferraz Pinto, MSc, RD

PhD Student, University of Campinas

School of Nursing, Campinas, Brazil

Tel: +55 19 3521-8838

E-mail: i152604@dac.unicamp.br

Received date: February 02, 2016; Accepted date: March 07, 2016; Published date: March 11, 2016

Citation: Pinto IF, Pereira JL, Campos CJ, Thompson JL (2016) The Dietitian’s Role in Palliative Care: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Scope and Emerging Competencies for Dietitians in Palliative Care. J Palliat Care Med 6:253. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000253

Copyright: © 2016 Pinto IF, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Objective: This study aims to explore the thoughts and perspectives of dietitians working in palliative care with respect their roles and contributions.

Methods: Semi-structured interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis. Seven European dietitians who worked in palliative care services were interviewed.

Results: Dietitians functioned as members of teams and performed activities such as nutritional assessment, formulation and monitoring of nutritional support plans, interfacing with food services, research and training. Dietitians viewed their professional input as positive to the team’s standard of care, patients’ outcomes and sense of comfort, and families’ satisfaction levels. They conveyed the desire to have a stronger and more established presence in palliative care and identified the need to clarify the benefits of their roles to palliative care, and documented a lack of continued professional development and network opportunities.

Conclusion: This study offers useful insights into the unique role of dietitians in specialist palliative across a number of domains, and highlights unique competencies required by dietitians working with this patient population. It also identifies several needs related to professional development. More research is needed to further document not only the roles of dietitians in palliative care, but importantly their impact on patient outcomes.

Keywords

Dietitians; Palliative care; Cancer; Professional practices; Professional role; Professional competence; Qualitative study

Introduction

Given the emerging importance of nutritional strategies in caring for palliative patients and families, there has been a call for the inclusion of dietitians in palliative care services [1,2]. While this is particularly relevant in the context of intervening and initiating palliative care much earlier in illness trajectory, it also applies to optimizing the eating experience and its related quality of life in the context of very advanced disease [3-5].

The role of dietitians in specialist palliative care teams has received scant attention in the literature. For example, the presence of dietitians and their involvement in this setting were not explored in a large European survey of palliative care units [6]. There is some evidence to suggest that nutrition is still undervalued in the European health care system, often due to lack of awareness and education [7,8].

This may also be explained by a focus on end-of-life, terminal care by many hospices and palliative care units, when nutritional interventions are often no longer considered feasible [9].

In addition, there is a lack of empiric evidence exploring the impact of nutritional services on quality of life domains for patients and families [10]. Moreover, there is little data on how dietitians view their role and the impact of their interventions within palliative care services and teams.

To address some of these gaps in the literature, the goal of this study was to explore the thoughts and perspectives of dietitians working in palliative care with respect to their roles and contributions in specialist palliative care services.

Methods

Study design

This qualitative study used a phenomenological approach, as it was felt that this would most suit the research goals and provide important early insights [11]. The data collection for this study was conducted in 2007. The study was approved by the Department of Exercise and Health Sciences, University of Bristol Human Participants Ethics Committee (reference number 011-07).

Selection and recruitment of participants

Criteria for eligibility for study participation included certified dietitians that were working in European palliative care services or units and had the ability to understand and communicate in conversational-level English. The study was restricted to Europe, as the lead author and co-authors were stationed in Europe at the time.

A purposive, four-staged sampling method was undertaken to identify potential study participants. The first step involved directly contacting individuals considered palliative care leaders in Europe, asking them to identify palliative care units and services across Europe that they knew included dietitians in the services.

A literature review was also conducted to identify potential centres and services. These two steps yielded 26 potential services and, in the second phase, the leads of these services were contacted. Fourteen (54 %) replied, ten of which reported having a dietitian on the service. In the third stage, these dietitians were then approached by letter with an invitation to participate in the study; seven agreed to participate (no responses were received from the other three). Using a snowball sampling approach, the last phase of recruitment involved asking the dietitians who had agreed to participate to in turn identify other potential participants that they know of. This yielded no further potential participants.

Data collection

Semi-structured individual phone interviews were used for data collection. A set of guiding questions was developed and tested in a pilot interview, conducted by a Canadian dietitian experienced in palliative care.

The questions related to: the interventions the dietitians provided in the services, how they felt they were perceived by the colleagues in those services and patients, their perceived impact on care, and their thoughts on the future role of dietitians in palliative care services. Socio-demographic and descriptive data related to the dietitians’ work allocation and work place were also collected.

Prior to conducting interviews, the participants were sent a participant information sheet that informed them of the details of the study, and any questions about the research were addressed by the lead author.

Before the beginning of each interview, the Informed Consent form was reviewed and discussed, and participants provided consent verbally. All interviews were tape-recorded and field notes were also kept. Interviews were anonymised and transcribed verbatim.

Member checking was done for those participants who at the end of the interview considered the use of oral English as a barrier to the full expression of their opinions; these individuals were asked to read the transcripts and make modifications as required, to better reflect their views and perceptions based on the questions posed.

Data analysis

The thematic analysis technique suggested by Miles and Huberman was used for data analysis [12]. Firstly, the researcher read and reread the transcripts in order to gain an holistic overview of the participant’s perceptions and opinions captured in the interview.

Codes were analytically developed and fixed to sets of the transcripts. These codes were transformed into themes after coded data had been sorted into broader categories.

Emergent themes were then organised into central and sub-themes. During this stage, the study supervisor (JLT) reviewed the transcripts to cross check the coding strategy. After the completion of the previous stages, conclusions were identified and drawn in constant relation to the research focus.

The findings were later discussed with the third member of the research team (JP) to support consistency and rigour [13]. Verbatim data were included in the research findings to ensure transparency, to make data explicitly available and understandable to the reader [13].

Results

Demographic data

Participants’ demographic data and a brief description of the services they were affiliated with are presented in Table 1.

| Participant | Gender | Age | Country | Work Place | Palliative Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience (years) | Time allocation to Palliative Care (%) | Service | Patients | |||||

| D1 | Female | 48 | Germany | General Hospital | 2.5y | 20% | In-patient unit | In-patients and Out-patients |

| D2 | Female | 27 | Spain | General Hospital | 3.7y | 50% | Ambulatory consultation | Out-patients |

| D3 | Female | 42 | Germany | Cancer Hospital | 10y | 30% | Palliative Care team assisting all hospital | In-patients and Out-patients |

| D4 | Female | 44 | Portugal | Cancer Hospital | 3y | 14% | In-patient unit with ambulatory consultation | In-patients and Out-patients |

| D5 | Male | 36 | Switzerland | Hospice | 12y | 100% | Hospice | In-patients |

| D6 | Female | 49 | Switzerland | General Hospital | 15y | 30% | In-patient unit with ambulatory consultation | In-patients and Out-patients |

| D7 | Female | 34 | Belgium | General Hospital | 4y | 25% | Oncology Unit | In-patients |

Table 1: Socio-demographic and detailed working characteristics of participants.

Qualitative data: Roles of the dietitian working in palliative care services:

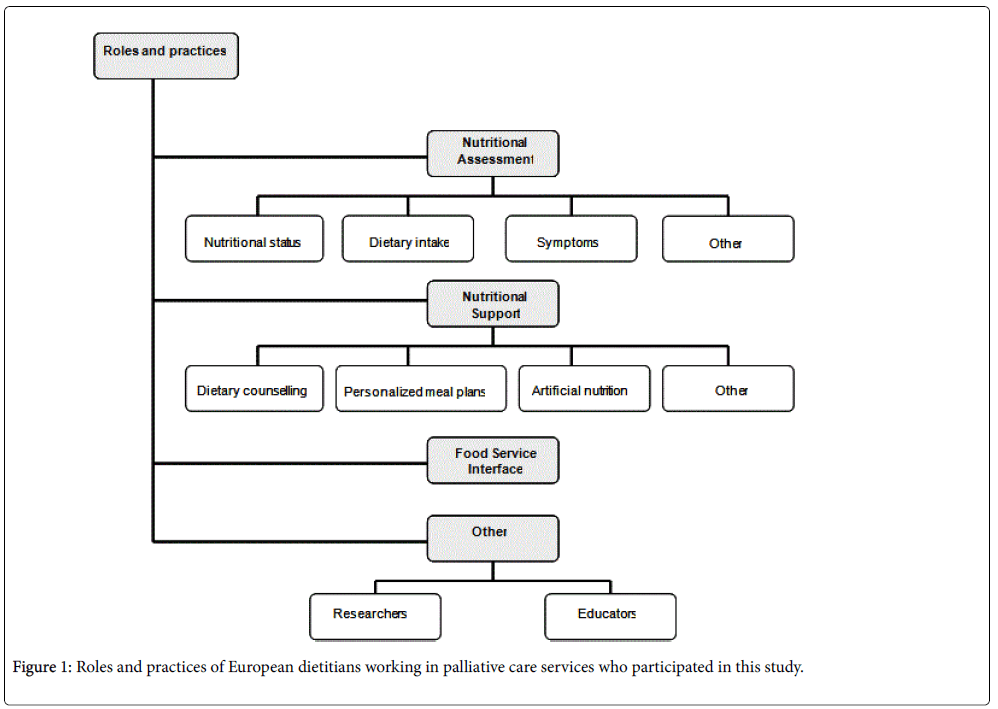

Several roles emerged during the interviews, including nutritional assessment, nutritional support, and liaising with the facility’s Food Services (Figure 1). In addition to these key tasks, dietitians were also participating in research on the services and providing education to other health professionals.

More specifically, their work involved the following: 1) processing referrals, 2) assessing patients’ clinical data and soliciting important clinical information about the patients from other team members; 3) informing the team about the results of the nutritional assessments; 4) discussing and establishing realistic nutritional goals; 6) developing nutritional care and treatment plans; 7) undertaking and reporting patients’ nutritional follow-ups and making adjustments to the initial nutritional care plan; and 8) collaborating with other team members in the preparation of discharge plans if needed.

Despite using different approaches and combinations of methods, all participants reported that the nutritional assessment included: 1) an assessment of nutritional status, with particular consideration of weight history; 2) an evaluation of dietary intake and food preferences; and 3) the identification of nutrition-related symptoms and other problems impacting patients’ ability to eat and enjoy meals. Often dietitians also solicited input from family members.

“We have structured and defined questionnaires for the assessment. (…) my assessment is to ask for symptoms: like the weight, how much he lost and kept the weight, the stress level of eating disorder, forappetite, digestion, dysgueusia, dysphagia, and so on. And we have a scale, this scale is from zero to ten (…). And I also make (…) a twoday diary for food and beverages. (…) And usually I got to measure and to weigh them (…).”

D6

Nutritional support involved dietary counselling, developing personalized meal plans and overseeing artificial nutrition (enteral and parenteral feeding) in those patients who were receiving these. Providing dietary counselling to enhance symptom control constituted an important part of their dietetic practice.

“What we usually do is to give them nutritional counselling mainly about symptom control and also problems that arise from previous treatments that they have been submitted to. So, we give them nutritional information regarding particular symptoms, and also a lot of dietetic tips, such as meals and sauces, that will help them to accomplish their nutritional needs (…).”

D2

Within dietary counselling, texture modification and increasing energy/ protein density were common strategies. Often the implementation of nutritional support plans also included the prescription of personalized meals.

“(…) we are going to suggest different kinds of meals or food, a so called ‘guided selected individualized meal.’ In cooperation with the patient, we try to arrange food, snacks or meals. Examples would be a piece of melon, yogurt, a simple creamy soup or spaghetti with tomato sauce. It is important to offer small but frequent portions.”

D3

“(…) working with palliative patients is a great challenge and offers a range of possibilities. The current health situation of the patient dictates the dietetic intervention. Terminally ill patients need different dietetic support than patients in earlier stages of their disease.”

D3

In some cases, nutrition support included the prescription of nutritional supplements.

“I usually recommend them [supplements] if I realize that a patient has diminished his intake or is not eating a specific type of food, for instance they are struggling to eat meat or fish due to taste alterations. Also, if their caloric and protein intake is low due to anorexia or early satiety, I usually use them. (…).”

D2

Dietitians also find themselves in the role of providing psychological support to patients and families, particularly given the social significance of eating and meals, and providing nutritional counselling. They felt that they were well placed to provide information to allay patients’ and family members’ fears around food-related issues. Dietitians involved in the discharge of in-patients reported working closely with other health professionals both within and outside their facilities.

“There is also a need to include the relatives into the counselling and explain the dietetic strategy so that they know how to support the patient.”

D3

“(…) maybe I need to contact the home care service for enteral nutrition, or it might be necessary that I contact (…) nursing home (…), or it might be necessary to call another dietitian in a rehabilitationcentre, and tell her what we have done especially with enteral nutrition, or it might be possible that I have to contact health insurance for cost items for drink supplements or enteral nutrition.”

D6

For dietitians working with in-patients, to interface with food services was an integral part of their daily practice. Dietitians reported that in order to produce personalized meal plans they maintained close working relationships with catering services.

“In our clinic, there is a close cooperation between dietitians and cooks. It is important that dietitians know which kind of meals they can offer while working out an individualized menu with the patient.”

Many of the participants were involved in education of other health care professionals and catering staff. Two dietitians also reported they took part in research studies developed within their palliative care services.

“(…) we train ourselves and also other professional groups. We share our knowledge with doctors, psychologists, nurses, and also with our food service system which consists of waiter/ waitress, cooks and kitchen staff. (…) it is important to sensitize this profession group [food service staff] also to the needs of palliative care patients.”

D3

“(…) we are involved in some research studies, in fact we are about to start one with glutamine with head and neck cancer patients. (…) This year we have presented in a nutrition congress, (…) our results from this year’s consultation.”

D2

Dietitians’ perceptions of the value of their contributions

A summary of themes and sub-themes related to the perceptions of study participants with respect to the perceived value of their roles is reported in Figure 2. The main themes indicate the value of their work related to patients, families and the rest of the palliative care team.

With respect to patients, dietitians reported several perceived benefits related to their interventions. Dietetic consultations were often an opportunity for patients to discuss problems or issues they were unable to raise with other health care professionals. Dietitians were also seen as a source of reliable information related to nutrition in advanced diseases, and they felt that the nutritional support plans positively impacted upon patient’s symptom control and general wellbeing.

“(…) they don’t talk with the oncologist about these issues. They can’t because the oncologist has never given them some kind of nutritional information or guidance on this topic, so yes they are thankful for coming to our consultation.”

D2

“These patients are often confused by a smattering of information about so-called ‘cancer diet’ (..).”

D3

“If patients notice that specific food choices or meals help them to gain weight or reduce digestive problems, they are grateful in realizing that their quality of life is improving.”

D3

With respect to patients, dietitians reported several perceived benefits related to their interventions. Dietetic consultations were often an opportunity for patients to discuss problems or issues they were unable to raise with other health care professionals. Dietitians were also seen as a source of reliable information related to nutrition in advanced diseases, and they felt that the nutritional support plans positively impacted upon patient’s symptom control and general wellbeing.

“(…) they don’t talk with the oncologist about these issues. They can’t because the oncologist has never given them some kind of nutritional information or guidance on this topic, so yes they are thankful for coming to our consultation.”

D2

“These patients are often confused by a smattering of information about so-called ‘cancer diet’ (..).”

D3

“If patients notice that specific food choices or meals help them to gain weight or reduce digestive problems, they are grateful in realizing that their quality of life is improving.”

D3

Dietetic counselling was thought to assuage patients’ fears and discomfort around food and eating, especially given the emotive and social meaning of food and its links to nurturing and even perceived survival. Dietitians recognized that for many of their patients, the ability to continue to eat was related to staying alive.

“(…) I should say that food is something very important to patients and families, because it is a daily life issue. Something that they have to do every day such as taking their medication, and it is something vital in their lives, you know in the same way they have to get up in the morning, they have to eat. They are very thankful for the help you give to eat better and easily and that through this help meal times are no longer a moment of fear or horror or frustration.”

D2

“(…) the food is like a fight, so if they can eat or they can have appetite or think of anything to eat, (…), it goes into their fight to live.”

D4

Some of the participants stated that through food, patients were able to retain some sense of control even in the context of advancing disease.

“(…) many patients have told me that eating is the only thing within their disease that they can dominate, and when they feel they are losing control of it that is something that affects them terribly, especially in a psychological way.”

D2

Dietitians felt that their roles were more limited in patients who were significantly depressed and did not want to receive treatment or in patients in the terminal phase. They interpreted non-intervention in these cases as an example of good practice.

“And if they don’t value the work I think is not because of my person or my work, it’s more the situation, the terminal situation of the patient (…) And we see in the consulting hour when the patient is really depressed then my recommendations would not work, so it’s better that the psychologist sees him first, and I see him maybe a week or two later.”

D6

Their perceived positive impact on families had several dimensions. The significance of food and eating, as with patients, again played a central role. Many families have questions related to feeding, and families often express appreciation for the dietitian’s intervention in providing information and clarifying questions. In addition, they perceived that their counselling reduced anxiety and pressure amongst family members with respect to dietary issues.

“So, frequently they [family members] tell you that this consultation helps them and that this help is of great value to them. Because, usually they are distressed with the fact that they don’t know what to do, they don’t know what they should give or not to the patient in order to help them feel better.”

D2

“I remember, many years ago I had a patient (…) I recommended him to drink supplements (…) after a while, the wife come in and said: “my husband died in the meantime but you know the supplements, the drinks help him to keep the quality of life until a week before he died, he was able to sit in the car and drive around and enjoyed his life, as much as it was possible in the situation of sickness.”

D6

Participants expressed that educating family members about disease progression and the changing role of dietetic interventions in palliative care was sometimes helpful in diffusing conflict around food-related issues between patients and their caretakers.

“(…) talking with the family, helps them to also get some more tranquillity and helps them to know their limits, where they can go (…).”

D4

Participants generally felt that they were an integral part of the palliative care team, and that their presence and contributions to patient care were appreciated by the other team members.

The Future of Dietitians in Palliative Care Services

Participants were generally of the opinion that there is a lack of dietary assistance in palliative care services, and that this deficiency may affect the optimal provision of care.

All participants called for future professional recognition of the specialist role of the dietitian in a palliative care service. They expressed that their role in palliative care is still unrecognized and sometimes misunderstood by others. Some dietitians pointed out that their national palliative care associations did not recognize them as active members of palliative care teams.

“(…) many of my colleagues do not work in palliative care. They don’t know what is Palliative Care.(…) There is a palliative care unit in the hospital, but they do not work in there.

D1

(…) the doctor think [in reference to dietitian’s work] is only for obese people and they do not know what we can do, that there are many, many other things we can do for the patients (…).

D1

(…) legally dietitians and priests are not included, but the association did not set up laws. Like I mentioned before, who belongs to the palliative care team depends on the hospital.”

D3

Participants highlighted the importance of on-going research related to dietetics in palliative care as an important strategy to heighten recognition and increase awareness of the role of dietitians in palliative care services. They also expressed the need for networking as a professional group in this area, but several admitted that they knew of few colleagues in the same field.

“I think research is important also in this field. (…) I think that is very important to show that the personal support provided by dietitians really makes the difference. These specific studies support our daily work at the hospital, and also help us being recognized by the health care system.”

D3

“Actually, I cannot say that I know many colleagues that are working in the palliative [area]. I don’t know anyone.”

D6

The need for continued professional development, specific for dietitians already working in palliative care, was highlighted by participants. However, most of the participants were struggling to find educational opportunities for themselves in this area.

“If one dietitian from my team would decide, ‘I would like to go more to the palliative care unit,’ it’s difficult (…) we don’t have special training just for palliative care.”

D6

Discussion

Limited data have been published on the role of dietitians in specialist palliative care services and their impact on patient outcomes. This study offers preliminary but useful insights on the unique role of dietitians in specialist palliative care services, the impact of their work on patient care and the ever-growing skill sets they require. It begins to delineate the numerous roles of dietitians in these services, including nutritional assessments, developing nutritional plans and liaising with food services to ensure optimal patient-centered meal choices, for patients at various stages of their illnesses.

The need to clarify these roles and to map out the specific competencies required of the various disciplines working in interprofessional specialist palliative care services has been previously highlighted [14-16]. Firstly, competency and role maps make explicit the roles of these disciplines within such teams and bring value to their contributions. Secondly, they help clarify the respective roles of the different disciplines. These include tasks that are specific to the disciplines (such as the development of nutritional care plans in the case of the dietitian) and tasks that are common to all team members, such as enhancing psychological wellbeing. In this study, for example, dietitians described their role in addressing psychological distress of patients and families related to nutritional changes. These concerns are well documented in the literature [17-19]. Thirdly, they guide the development of educational programs to address the specific learning needs of these disciplines working in these settings. In this study, for example, dietitians working in palliative care services highlighted the lack of educational programs specifically targeting their learning needs.

It is important to differentiate between a discipline’s general competencies- skills that are transferrable from one care setting to another-versus more specialized skills that are unique to a specific patient population or care setting. In this study, dietitians highlighted some needs that are relatively unique to patients with progressive life limiting illnesses, and the competencies that they require to address these needs. These include cachexia related to advancing disease. Participants in this study highlighted specific issues related to enteral and parenteral feeding, and the need to modify treatment plans based on illness trajectories and goals of care. They referred to the communication skills required to inform patients with very advanced disease and their families of the limitations of artificial feeding, particularly when patients in these circumstances and families often ascribe healing significance to feeding and food [20].

There is a great need to integrate palliative care education within the generalist training of dietitians in the same way that is being advocated for other disciplines [21]. This study highlights the need for additional competencies for dietitians working in specialist palliative care services. This is not unique to dietitians. Cooper et al, for example, described a similar phenomenon amongst chaplains working in specialist palliative care services [15]. At the initiation of their project, the Canadian organization that accredits chaplains expressed reservations that chaplains in these teams required additional specialized knowledge and skills. It was felt that all chaplains are equipped with the appropriate skills sets during their education. However, the mapping of the competencies resulted in a heightened awareness and recognition of the specialist skill sets required in this unique patient population, resulting in the development of an educational program specifically for chaplains in specialist palliative care teams.

The need for specialist-level education for dietitians in palliative care is even more heightened given some important changes occurring in the field. There is, for example, an emerging recognition for the need to initiate palliative care earlier in the illness trajectories of patients with life threatening and life limiting illnesses, not only at the end of life in the last days or weeks [3]. This is accompanied by increased interest in palliative rehabilitation, in which nutritional interventions plays a key role alongside physical exercise programs and other interventions to reduce the impact of cachexia and asthenia [22-25]. This requires additional flexibility in decision-making by palliative care professionals to ensure that care plans and treatment decisions are individualized to the patient’s circumstances, including the stage of disease and goals of care. A recent study by Chasen et al. on the impact of an interprofessional palliative rehabilitation service that included a dietitian as a core team member, reported benefits across several areas, including weight and appetite [24]. An earlier study using a similar team approach with a dietitian in a cancer centre reported similar results; 77% of the patients with advanced cancer who completed a 10- week to 12-week cancer rehabilitation program maintained or increased their body weight [25].

There is also broadening of palliative care beyond cancer to include patients with non-cancer illnesses. Nutritional care, for example, is as important in many of these diseases as it is with cancer. This is accompanied by ethically charged situations such as reduced swallowing in patients with cancer and non-cancer diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and dementia [26-28].

The study also highlights the contributions of dietitians in research and education related to palliative care. Such contributions range from basic research and clinical trials in conditions such as cachexia and anorexia, to quality improvement initiatives related to nutrition. Pietersma et al. for example, in a Canadian dietitian-led study demonstrated the benefits of a food cart over traditional food tray services on a palliative care unit, both in terms of quality of life for patients and in terms of reduced wastage and costs [29]. Dietitians working in palliative care service in turn, with their clinical experiences, knowledge and skills in palliative and end-of-life care are useful resources as educators to assist in the education of generalist dietitians and dietitians seeking careers in palliative care.

Dietitians in this study reported that they felt that other disciplines in the palliative care services they worked in valued their roles and contributions. However, at a higher health services level, they expressed concerns that their role in palliative care is not adequately recognized in their respective countries. Participants unanimously called for future professional recognition and integration in this area. They also described a sense of professional isolation, in that there are few colleagues working in similar roles that they could turn to for networking and support. In fact, participants in this study suggested the need for a network of palliative care dietitians.

The study has several limitations. Firstly, it is a relatively small study. The population, in this case, palliative care dietitians in Europe, appears to be relatively small and it was difficult to find enough participants to allow the researchers to conduct enough interviews to achieve data saturation. Notwithstanding, there was a significant amount of overlap and consistency of what was being said by the small group of participants across different countries. While some may argue that the study size does not allow generalizability, the intent of qualitative studies is to gain insights into a phenomenon and allow readers to consider the transferability of the study. In this case, the data provided interesting and useful insights into the role of dietitians in palliative care services, and can serve as a stepping stone for larger studies in the future. Another potential limitation is related to the interviews being conducted in English, which was not the mother language of most of the participants. Allowing them to review the transcripts and make modifications was an attempt to mitigate this. The criterion of conversational fluency in English may have excluded valuable input from eligible participants.

Conclusions

This study offers useful insights into the unique role of dietitians in specialist palliative across a number of domains, from nutritional assessments and the development of nutritional care plans, to liaising with food services, psychological support of patients and families, research and education. The study highlights unique competencies required by dietitians working with this patient population, particularly given the involvement of palliative care across the whole continuum of the illness experience.

The study identifies several needs. These include: a) the need for increased recognition by professional bodies and health service planners of the role of dietitians in palliative care services; b) the need for more education programs for dietitians working in the field, particularly given the unique needs of this patient population; c) the need to establish a professional network for palliative care dietitians; and d) the need for more research to further document not only the roles of dietitians in palliative care, but even more importantly their impact on patient outcomes. These outcomes may not be the traditional ones generally associated with dietetics (e.g., weight and appetite gain), but outcomes related to quality of life and psychological wellbeing, both for patients and their families.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Fearon K, Arends J, Baracos V (2013) Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nat Rev ClinOncol 10: 90-99.

- Bosaeus I (2008) Nutritional support in multimodal therapy for cancer cachexia. Supp Care Cancer 16:447-451.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, et al. (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363: 733-742.

- Wallin V, Carlander I, Sandman PO, HakansonC (2015) Meanings of eating deficiencies for people admitted to palliative home care. Palliat Support Care 13: 1231-1239.

- Ravasco P, MonteiroGrillo I, Camilo M (2007) Cancer wasting and quality of life react to early individualized nutritional counselling. ClinNutr26: 7-15.

- Kaasa S, Torvik K, Cherny N, Hanks G, de Conno F (2007) Patient demographics and centre description in European palliative care units. Palliat Med 21: 15-22.

- Beck AM, Balknas UN, Furst P, Hasunen K, Jones L, et al. (2001) Food and nutritional care in hospitals: how to prevent undernutrition- report and guidelines from the Council of Europe. ClinNutr20: 455-460.

- Beck AM, Balknas UN, Camilo ME, Fürst P, Gentile MG, et al. (2002) Practices in relation to nutritional care and support-report from the Council of Europe. ClinNutr 21: 351-354.

- Good P, Cavenagh J, Mather M, Ravenscroft P (2008) Medically assisted nutrition for palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4: CD006273.

- Prevost V, Grach MC (2012) Nutritional support and quality of life in cancer patients undergoing palliative care. Eur J Cancer Care 21: 581-590.

- Creswell JW (2007) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Sage.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Data management and analysis methods: Handbook of Qualitative Research (2ndedn.) Sage, Thousand Oaks, California.

- Baillie L (2015) Promoting and evaluating scientific rigour in qualitative research. Nurs Stand 29: 36-42.

- Gamondi C, Larkin P, Payne S (2013) Core competencies in palliative care: an EAPC Whitepaper on palliative care education – part 1. Eur J Palliat Care 20: 86-91.

- Cooper D, Aherne M, Pereira J (2010) The competencies required by professional hospice palliative care spiritual care providers. J Palliat Med 13: 869-875.

- Cobbe S, Kennedy N (2012) Physical function in hospice patients and physiotherapy interventions: a profile of hospice physiotherapy. J Palliat Med 15: 760-767.

- Strasser F, Binswanger J, Cerny T, Kesselring A (2007) Fighting a losing battle: eating-related distress of men with advanced cancer and their female partners. A mixed-methods study. Palliat Med 21: 129-137.

- Reid J, Mckenna HP, Fitzsimons D, McCance TV (2010) An exploration of the experience of cancer cachexia: what patients and their families want from healthcare professionals. Eur J Cancer Care 19: 682-689.

- Hopkinson J, Corner J (2006) Helping patients with advanced cancer live with concerns about eating: a challenge for palliative care professionals. J Pain Symptom Manage 31: 293-305.

- Del Río MI, Shand B, Bonati P, Palma A, Maldonado A, et al. (2012) Hydration and nutrition at the end of life: a systematic review of emotional impact, perceptions, and decision-making among patients, family, and health care staff. Psychoonco 21: 913-921.

- Chiarelli PE, Johnston C, Osmotherly PG (2014) Introducing palliative care into entry-level physical therapy education. J Palliat Med17: 152-153.

- Santiago-Palma J, Payne R (2001) Palliative care and rehabilitation. Canc 92:1049-1052.

- Fearon KC (2008) Cancer cachexia: developing multimodal therapy for a multidimensional problem.Eur J Cancer 44: 1124-1132.

- Chasen MR, Feldstein A, Gravelle D, Macdonald N, Pereira J (2013) An interprofessional palliative care oncology rehabilitation program: effects on function and predictors of program completion. CurrOncol20: 301-309.

- Gagnon B, Murphy J, Eades M, Lemoignan J, Jelowicki M, et al. (2013) A prospective evaluation of an interdisciplinary nutrition-rehabilitation program for patients with advanced cancer. CurrOncol20: 310-318.

- Geppert CM, Andrews MR, Druyan ME (2010) Ethical issues in artificial nutrition and hydration: a review. J Parenter Enteral Nutr34:79-88.

- Raijmakers NJ, van Zuylen L, Constantini M, Caraceni A, Clark J, et al. (2011) Artificial nutrition and hydration in the last week of life in cancer patients. A systematic literature review of practices and effects. Ann Oncol22:1478-1486.

- Young J, Fawcett T (2002) Artificial nutrition in older people with dementia: moral and ethical dilemmas. Nurs Older People 14: 19-21.

- Pietersma P, Follet-Bick S, Wilkinson B, Guebert N, Fisher K, et al. (2003) A bedside food cart as an alternate food service for acute and palliative oncological patients. SuppCare Cancer 11:611-614.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 20165

- [From(publication date):

March-2016 - Jul 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 18822

- PDF downloads : 1343