The Current State of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV in Informal Health Centers in Cameroon

Received: 03-Apr-2023 / Manuscript No. JIDT-23-93920 / Editor assigned: 05-Apr-2023 / PreQC No. JIDT-23-93920 (PQ) / Reviewed: 20-Apr-2023 / QC No. JIDT-23-93920 / Revised: 27-Apr-2023 / Manuscript No. JIDT-23-93920 (R) / Published Date: 04-May-2023

Abstract

Background: Informal healthcare providers are key actors in the provision of healthcare among poor populations in developing countries. In 2017, Cameroon had more than 3,000 informal health facilities. In a context of elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, this study described the offer of Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) in informal health centers in Cameroon.

Methods: This two-phase cross-sectional study was conducted in two cities, Douala and Ebolowa, in Cameroon. The first phase was conducted from March to July 2019 in 110 informal healthcare centers and the second phase was conducted from August 2019 to January 2020 with 183 Healthcare Providers (HPs) in these facilities. Standardized questionnaires were administered and data was entered into koboCollect software. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression were used with a P <0.05 considered significant.

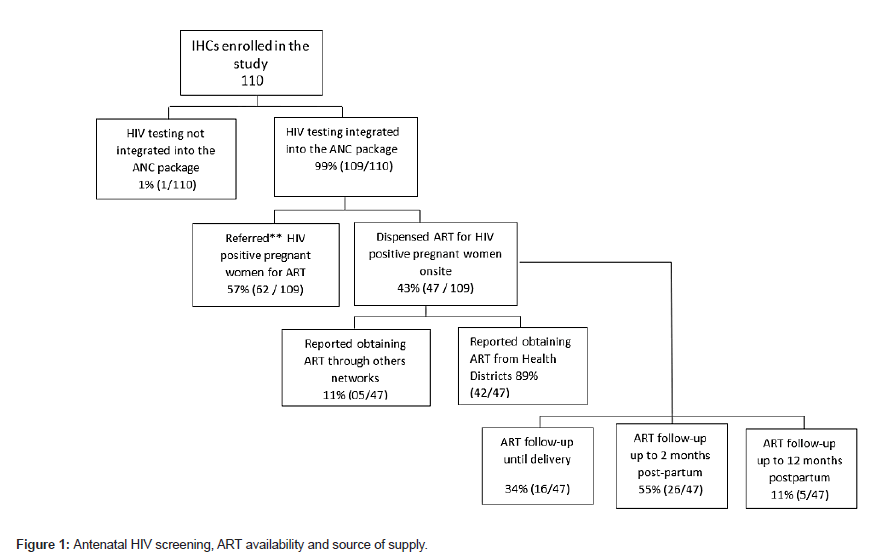

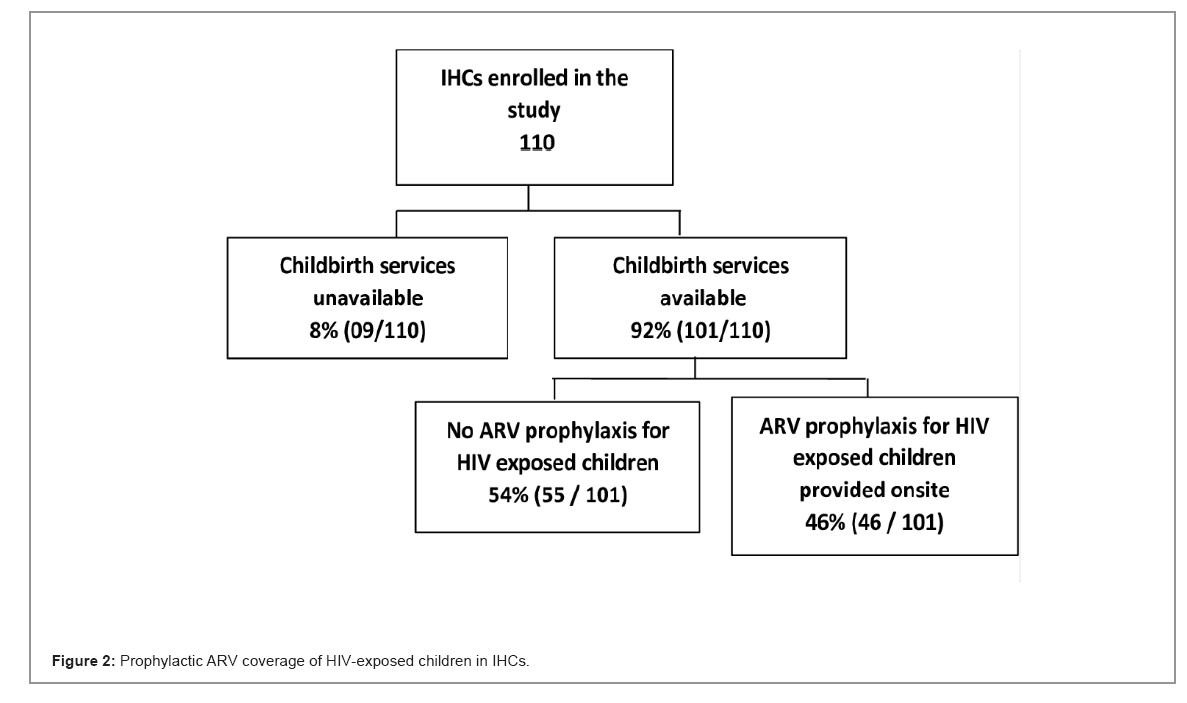

Results: A total of 109 of the 110 informal healthcare centers integrated HIV testing into their antenatal check-up packages. Of these, 43% (47/109) reported providing antiretroviral treatment to HIV-infected pregnant women, while the remaining referred these women to formal HIV care centers. Of 101 informal healthcare centers that offered childbirth services, 54%(55/101) referred HIV-exposed newborns to further PMTCT care. More than half of the HPs (51%; 94/183) had insufficient PMTCT knowledge and 90% (165/183) had an insufficient PMTCT practice level. The lack of PMTCT experience (adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=32.04, 95% CI: 6.29-163.10, p <0.001) and PMTCT training during the prior two years (aOR=3.02, 95% CI: 1.06-8.64, p=0.03) increased the chance of having insufficient knowledge of PMTCT in HPs. While working in IHCs that referred women for PMTCT (aOR=4.1, 95%CI: 1.18 à 14.13, p=0.02) increased their odds of having insufficient PMTCT practices..

Conclusion: Informal healthcare centers in Cameroun often perform illegal PMTCT activities. Given the low PMTCT knowledge and practices of healthcare providers in these informal healthcare centers, the national PMTCT program would benefit from the use of strategies to assure the safe care of HIV-positive pregnant women who are clients of these informal healthcare structures.

Keywords

Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV; Informal healthcare centers

Introduction

Various economic crisis and structural adjustment policies from the mid-1980s have had a serious impact on the creation of jobs and services in many African countries [1,2]. This has led to an exponential increase in poverty and the use of informal services across all sectors of society, including health [2]. Poor populations in low-income countries often resort to the use of informal healthcare providers for their healthcare needs, due to their geographical proximity, financial accessibility, and reduced waiting times [3-6].

The economic crisis of the 1980s led to a reduction in public health expenditure in Cameroon, including a decrease from 5% of the national budget in 1994 to less than 3% in subsequent years [7]. The immediate consequence was a deterioration of the health system, reduced quality of care, and the establishment of a vast network of informal healthcare providers [8-11]. This informal health network includes several actors, including street medicine vendors, traditional healers, and Informal Healthcare Centers (IHCs). In 2017, the Ministry of Public Health in Cameroon identified more than 3,000 informal healthcare facilities that operated in the national territory [12]. These functioned without an official act of creation or operation issued by health authorities.

Despite having limited technical facilities, IHCs often provide a wide range of services, integrating Antenatal Consultations (ANCs) and childbirth services [13,14]. ANCs are essential for the Prevention of HIV Transmission from Mother to Child (PMTCT), since they represent a critical entry point into the PMTCT cascade [15,16]. This is especially true when client demand-based HIV testing is very low. Thus, ANCs remain the major method of HIV testing among women [17]. This is particularly critical given that most pediatric HIV cases result from mother-to-child transmission [18-23].

Currently, very little is known about PMTCT activities performed by IHCs in Cameroon. As part of the ECIP PMTCT study conducted in Douala and Ebolowa, We described the current state of PMTCT activities in these two cities. Specifically, this work involved analyzing PMTCT activities and assessing the knowledge and practices of PMTCT staff. Factors associated with an “insufficient” level of knowledge and practices among Healthcare Providers (HPs) in these IHCs were also assessed.

Materials and Methods

Study design setting and population

A two-phase descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in two cities, Douala and Ebolowa, in Cameroon. The first phase, conducted from March to July 2019, involved an analysis of the PMTCT activities provided by IHCs, that offered antenatal care and/or childbirth services. The second phase, conducted from August 2019 to January 2020, assessed the level of PMTCT knowledge and practices of HPs, who worked in the above-mentioned services. A total of 110 IHCs were registered, including 88 in Douala and 22 in Ebolowa; and 183 HPs were enrolled, including 131 in Douala and 52 in Ebolowa.

Procedures

Informal healthcare center definition: An IHC was defined as any secular private health facility with a fixed location that offered ANCs and lacked an official, government-issued, act of creation or operation, and functioned without physicians.

Informal health care center selection: A health map of Cameroon was used to select IHCs in Douala and Ebolowa. Douala has nine health districts, Boko, Japoma, Nylon, Bangue, Deido, Cité des Palmiers, Bonassama, Newbell, and Logbaba, of which the following seven were randomly selected: Nylon, Bangue, Deido, Cité des Palmiers, Bonassama, Newbell, and Logbaba. Since Ebolowa has only one health district: the entire district was retained. Research assistants who were recruited for the study were given a starting point in each health district, that served as the benchmark for the census of IHCs.

Data collection and statistical analysis: Using the PMTCT assessment tool developed by Family Health International, a questionnaire was developed to capture information about PMTCT services offered [24]. The questionnaire collected data on the availability of ANC services, the integration of HIV testing into ANC, the supply of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) to Pregnant Women Living with HIV (PWLHIV), the ART supply source, the availability of delivery services, the availability of prophylactic ARVs for HIV exposed newborns, the HIV tests used to identify infection, and the duration of mother-child followup among IHCs providing on-site HIV care.

A standardized questionnaire, designed from the 2019 national guidelines on the prevention and care of HIV in Cameroon, was also used to assess PMTCT knowledge and practices by HPs [25]. A total of fourteen and seven questions that evaluated PMTCT knowledge and practices, respectively, were used. The questionnaire included an important section on sociodemographic data: town, type of PMTCT site, sex, health training qualification, type of PMTCT training received, years of experience in PMTCT, and history of formal PMTCT training during the last two years.

PMTCT knowledge questions included HIV source, the primary route of HIV infection in children, lack of ARV coverage in PWLHIV and the risk of HIV infection in the child, lack of ARV prophylaxis coverage in the child and risk of HIV infection, ARV protocol recommended as the first-line treatment for PWLHIV, initiation of ART in PWLHIV, ARV prophylaxis in HIV-exposed children, recommended ARV prophylaxis in exposed children, duration of ARV prophylaxis, knowledge of early diagnosis for HIV-exposed children, the recommended age for early diagnosis of HIV-exposed children, initiation of Cotrimoxazole treatment of HIV-exposed children, recommended timing for stopping Cotrimoxazole treatment of HIVexposed children, and breastfeeding for the first six months of life in HIV-exposed infants born to women on ART.

Practices were assessed using the following questions: systematic HIV testing of pregnant women, HIV post-test counseling, proposals/reminders about the importance of ARV treatment of PWLHIV, encouragement of HIV status disclosure to male partners, administration of and reminders about ARV prophylaxis in HIV exposed children, reminders to HIV mothers about the importance of early infant diagnosis of HIV in exposed children, and referral procedures for additional PMTCT services. All data were entered into KoboCollect.

Descriptive analyses of the sociodemographic variables were performed. To assess the level of PMTCT knowledge and practices, one point was assigned for each correct response and zero points was assigned for each incorrect response. Thus, total scores ranged from 0 to 14 for PMTCT knowledge and 0 to 7 for PMTCT practices. The percentage of correct scores in each category was determined as the number of correct answers divided by the total number of questions. Overall knowledge and practice levels were categorized as “insufficient” if the score percentage was less than 80% and “sufficient” if the score percentage was 80% or above [26]. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with insufficient PMTCT knowledge and practices in HPs at a significance level of p <0.05. Covariates included town, type of PMTCT site, sex, health training qualification, years of experience in PMTCT, and formal training on PMTCT in the prior two years. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0.

Results

PMTCT service in the IHCs

Almost all of the IHCs (109/110) had integrated HIV screening within their antenatal check-up packages. The final decision to diagnose HIV disease was preceded by the successive determination of HIV infection using the Determine HIV 1/2 and OraQuick HIV 1/2 tests/strips, two HIV rapid tests recommended by the Cameroon National HIV Testing Algorithm [25].

Of the 109 IHCs that had integrated HIV screening within their ANC protocols, 43% (47/109) reported providing ART to PWLHIV (Figure 1). More than half of the IHCs (26/47) followed PWLHIV for a period of two months after delivery. According to IHCs, ART was supplied by public health structures (health districts, public health facilities) for 89% (42/47) and by other IHCs for the remaining 11% (05/47). Given the illegality of IHCs, none of those dispensing ARVs were receiving support (formative) supervisions. Among the IHCs that referred PWLHIV to formal HIV care centers, the referral was generally verbal, without any documentation issued to the patient. Only the name of the HIV care center was communicated.

Child birth services were offered by 92% (101/110) of the IHCs. More than half (54%; 55/101) of the IHCs referred HIV-exposed children for Nevirapine prophylaxis and further PMTCT care, while 46% (46/101) provided this prophylaxis (Figure 2). None of the IHCs dispensed Cotrimoxazole or collected blood samples for early infant diagnosis.

Healthcare provider knowledge and practices of PMTCT

HPs description: A total of 183 HPs were enrolled in the study, with a median age of 37 years (IQR, 30-44). Most HPs were female (81% (149/183)), 56% (103/183) were nurse assistants, and 7% (12/183) had no documented health training. About 28% (51/183) of HPs worked currently, or had worked, as Public Servants in public health facilities; of whom 84% (43/51) were retired while the remaining 16% (8/51) were still working in those public health facilities. All of these former or current Civil Servants were owners of the IHCs.

Most of the HPs (84% (154/183)) had received PMTCT training from their colleagues, while only 13% (23/183) had received formal PMTCT training through workshops or seminars in the prior two years. Slightly more than half of HPs (58%; 107/183) had less than five years of PMTCT experience, while 14% (25/183) had no experience with PMTCT (Table 1).

PMTCT knowledge: The median score on the PMTCT knowledge questions was 79% (IQR, 71-93). Only 49% (89/183) of HPs had sufficient PMTCT knowledge (scores ≥ 80%). The question that registered the lowest score was “Should an HIV-infected woman on ART breastfeed her child for the first six months of life?” Indeed, only 32% (58/183) of HPs followed 2019 Cameroon’s National guidelines and answered yes to this question (Table 2).

PMTCT practices: The median score on the PMTCT practice questions was 43% (IQR, 29-57). Only 10% (18/183) of HPs had a sufficient level of PMTCT practices (Table 3). Procedures for referring HIV mothers to an HIV care unit was the item that scored lowest. Generally, only 8% (15/183) of HPs reported the use of good practices on this item.

It should also be noted that less than half (40%) of the HPs administered HIV post-test counseling to PWLHIV. HIV results were announced to PWLHIV in a confidential room and the recommendation to start treatment to prevent disease progression and HIV transmission to the child was provided. In addition, very few HPs (15%) discussed partner involvement with PWLHIV, including result sharing and HIV counseling and testing of male partners (Table 3). About 7% (12/183) of HPs had both sufficient level of PMTCT knowledge and practices while 48% (88/183) had neither sufficient knowledge nor PMTCT good practices PMTCT during the prior two years.

Factors associated with poor knowledge and practices of PMTCT: In bivariate analyses, HPs with no documented health training qualification had a higher chance of having insufficient PMTCT knowledge than registered nurses (OR=7.35, 95% CI: 1.28-50, p=0.02). HPs with no PMTCT experience had greater odds of having insufficient PMTCT knowledge than those with 5 years of experience or more (OR=41.81, 95% CI: 8.51-205.38, p <0.001). HPs who did not received formal PMTCT training during the past two years also had higher odds of having insufficient knowledge than those who did receive training (OR=2.72, 95% CI: 1.06-6.99, p=0.037).

The multivariable logistic model showed that the lack of formal PMTCT training during the prior 2 years, and the lack of PMTCT experience were associated with insufficient PMTCT knowledge (Table 4). Indeed, HPs with no history of formal PMTCT training during the past two years had higher odds of having insufficient PMTCT knowledge relative to those who were formally trained (adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=3.02, 95% CI: 1.06-8.64, p=0.03). Moreover, HPs with no PMTCT experience had greater odds of having insufficient PMTCT knowledge than those with 5 years’ experience or more (aOR=32.04, 95% CI: 6.29-163.10, p<0.001).

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| City (n=183) | ||

| Douala | 131 | 72 |

| Ebolowa | 52 | 28 |

| Type of PMTCT site (n=183) | ||

| Refer for ART | 119 | 65 |

| Give ART | 64 | 35 |

| Sex (n=183) | ||

| Female | 149 | 81 |

| Male | 34 | 19 |

| Former or current Civil Servant(n=183) | ||

| Yes | 51 | 28 |

| No | 132 | 72 |

| Health training qualification (n=183) | ||

| No documented health training | 12 | 7 |

| Nurse assistant | 103 | 56 |

| State certified Nurse | 35 | 19 |

| Registered nurse | 14 | 8 |

| Laboratory technician | 19 | 10 |

| Type of PMTCT training received (n=183) | ||

| None | 2 | 1 |

| By colleagues | 154 | 84 |

| Documents reading | 4 | 2 |

| Seminars / workshops | 23 | 13 |

| Years of experience in PMTCT(n=183) | ||

| None | 25 | 14 |

| < 5 years | 107 | 59 |

| 5-10 years | 41 | 22 |

| >10 years | 10 | 5 |

| Formal PMTCT training during the last 2 years (n=183) | ||

| Yes | 23 | 13 |

| No | 160 | 87 |

Table 1: Characteristics of Health providers in informal health centers.

For PMTCT practices, HPs who worked in IHCs in Douala (urban setting) were more likely to have poor PMTCT practices than those working in Ebolowa (semi-rural setting) lack (OR=3.66, 95%CI: 1.35- 9.88, p=0.01). HPs who lacked formal PMTCT training in the prior 2 years were also more likely to have poor PMTCT practices than those who were formally trained (OR=4.35, 95% CI: 1.44-13.09, p=0.009).

Moreover, HPs who worked in IHCs that referred PWLHIV for ART (a OR= 4.34, 95%CI: 1.54-12.21, p=0.005) had higher odds of having insu -fficient PMTCT practices than those working in ANC integrating ART. In multivariable model, insufficient practices were associated with work ing in IHCs located in Douala (urban setting) (aOR= 4.77, 95% CI: 1.63 - 13.92, p=0.004) and working in IHCs that referred PWLHIV for ART (aOR= 4.1, 95%CI: 1.18-14.13, p=0.02)

| Items | Correct |

|---|---|

| HIV source | 100% |

| Primary route of HIV infection in children | 99% |

| Lack of ARV coverage in PWLHIV and the risk of HIV infection in the child | 83% |

| lack of ARV prophylaxis coverage in the child and risk of HIV infection | 77% |

| ARV protocol recommended as first line treatment for PWLHIV | 60% |

| Initiation of ART in PWLHIV (When to start) | 96% |

| ARV prophylaxis in HIV exposed children (when to start) | 83% |

| Recommended ARV prophylaxis in HIV-exposed children | 85% |

| Duration of ARV prophylaxis in HIV-exposed children | 76% |

| Knowledge of early diagnosis for HIV-exposed infants | 94% |

| Recommended age for early diagnosis of HIV-exposed children | 85% |

| Initiation of Cotrimoxazole treatment of HIV-exposed children (When to start) | 50% |

| Recommended timing for stopping cotrimoxazole in HIV-exposed children | 77% |

| Breastfeeding for the first six months of life in HIV-exposed infants born to women on ART | 32% |

| Overall knowledge score | |

| Median (IQR) | 79% (71-93) |

| Less than 80% (insufficient) | 51% |

| 80% or more (sufficient) | 49% |

Table 2: Health providers knowledge on PMTCT.

| Items | Correct |

|---|---|

| Systemic proposal of HIV testing to pregnant women | 100% |

| Practice of HIV post-test counseling | 40% |

| Proposals/reminders of the importance of ARV treatment to PWLHIV | 52% |

| Encouragement of HIV status disclosure to male partners | 15% |

| Administration of and reminders about ARV prophylaxis in HIV exposed children | 52% |

| Reminders to HIV mothers about the importance of early infant diagnosis of HIV in exposed children | 48% |

| Referrel procedures for additional PMTCT services | 8% |

| Overall practice score | |

| Median (IQR) | 43% (29-57) |

| Less than 80% (insufficient) | 90% |

| 80% or more (sufficient) | 10% |

Table 3: Health Providers practices on PMTCT.

| Bivariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | aOR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Town (n=183) | |||||

| Ebolowa | 1 | - | - | - | |

| Douala | 1.49 (0.78-2.84) | 0.22 | - | - | - |

| Type of PMTCT site (n=183) | |||||

| PMTCT follow-up site | 1 | - | - | - | |

| Refer for PMTCT | 0.98 (0.53-1.81) | 0.96 | - | - | - |

| Sex (n=183) | |||||

| Male | 1 | - | - | - | |

| Female | 0.59 (0.27-1.27) | 0.18 | - | - | - |

| Health training qualification (n=183) | 0.19 | ||||

| Registered nurse | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| State certified nurse | 2.12 (0.53-8.33) | 0.28 | 1.63 (0.35-7.69) | 0.53 | - |

| Lab technician | 0.53(0.10 –2.77) | 0.45 | 0.49 (0.08-3.03) | 0.43 | - |

| No documented health training | 7.69 (1.28 – 50) | 0.02 | 3.44 (0.48-25) | 0.21 | - |

| Nurse assistant | 2.04 (0.57-7.69) | 0.26 | 2 (0.47-8.13) | 0.34 | -- |

| Years of experience in PMTCT(n=183) | <0.001 | ||||

| 5 years and more | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| 4.64 (2.15-10.01)<0.0014.50 (2.0-10.15)<0.001- | |||||

| None | 41.81 (8.51-205.38) | <0.001 | 32.04 (6.29-163.10) | <0.001 | - |

| Formal training on PMTCT | |||||

| Yes | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 2.72 (1.06-6.98) | 0.03 | 3.02 (1.06-8.64) | 0.03 | - |

Table 4: Factors associated with insufficient level of PMTCT knowledge.

| Characteristics | Bivariate analyses | Multivariate analyses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | aOR (95% CI) | P | |

| Town (n=183) | ||||

| Ebolowa | 1 | 0.01 | - | - |

| Douala | 3.66 (1.35-9.88) | 4.77 (1.63-13.92) | 0.004 | |

| Type of PMTCT site (n=183) | ||||

| Provide ART | 1 | 0.005 | - | - |

| Refer for ART | 4.34 (1.54-12.21) | 4.10 (1.18-14.13) | 0.02 | |

| Sex (n=183) | ||||

| Male | 1 | 0.16 | - | - |

| Female | 0.23 (0.03-1.83) | - | - | |

| Health education (n=183) | ||||

| No documented health training | 1 | - | - | - |

| State certified nurse | 1.20 (0.20-7.18) | 0.84 | - | - |

| Lab technician | 3.60 (0.28-44.82) | 0.31 | - | - |

| Registered Nurses | 1.20 (0.14-10.11) | 0.86 | - | - |

| Nurse assistant | 2.37 (0.44-12.75) | 0.31 | - | - |

| Years of experience in PMTCT (n=183) | ||||

| None | 1 | - | - | - |

| 0.40 (0.04-3.31)0.39 - - | ||||

| 5-10 years | 0.30 (0.03-2.73) | 0.28 | - | - |

| >10 years | 0.16 (0.01-2.09) | 0.16 | - | - |

| Formal PMTCT training in the past two years (n=183) | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 0.009 | - | - |

| No | 4.35 (1.44-13.09) | 2.12 (0.56-8.02) | 0.26 | |

Table 5: Factors associated with low levels of PMTCT practice.

Discussion

Integration of HIV screening into ANC services of IHCs

This study reported on the current state of PMTCT in IHCs in the cities of Douala and Ebolowa, the capitals of the Littoral and South Regions in Cameroon, respectively. Almost all IHCs with ANC services (99%) integrated HIV testing into antenatal laboratory exams. Cameroon National PMTCT data from 2019 showed that HIV testing coverage in the Littoral and South Regions was 98.2% and 93.7%, respectively. These was above the national coverage of 82.8% [27]. This suggests that in the formal ANC services in these regions, HIV screening is deeply integrated into antenatal laboratory exam package. IHCs followed this trend.

ARV supply sources

Some IHCs reported receiving their ARV supplies from public health structures, likely via informal networks. Health districts are at the periphery level of the health pyramid in Cameroon, responsible for supplying linked health facilities with ARVs. However, these supplies are intended for health facilities registered by the Ministry of Public Health; and staff who use them often benefit from training supervision. Thus, the presence of ARVs in IHCs is likely the result of a dysfunctional ARV supply circuit. This is particularly relevant given that some owners of IHCs have been or remain simultaneously linked to public health structures. The double affiliation of these healthcare providers to formal and informal healthcare facilities may explain the ease of ARV flow between public health structures and IHCs.

The diversion of ARVs from health facilities to informal circuits has been previously described both in Cameroon and elsewhere. Indeed, during a press conference on August 25, 2009, the Cameroonian Minister of Public Health was alarmed that ARVs and other pharmaceutical products were being diverted from public hospitals to informal circuits [28]. In addition, an IRD research team in Senegal, along with other partners, assessed the circulation of ARVs outside the national program during 2000-2002. An analysis of the batch numbers of supplies found in the informal circuits, revealed that the ARVs primarily originated from diversions from health structures. However, the flow of ARVs from the national program to informal networks was low, with 13 of 21,0000 supply boxes distributed by the national ARVs program found on the informal market during 1998-2002 [29].

The results of the current study show that, unlike other informal health providers, such as traditional healers or medicine street vendors, that typically have little or no formal health training, most IHC staff had been formally trained. While some IHC owners were current or retired civil servants, others were unable to integrate into the formal healthcare system. Similar results were found in studies of informal HPs in Nigeria. These studies have shown that while some informal providers have adequate formal health training, they found themselves working in the informal sector after being unable to obtain a position in the formal healthcare system, and needing to generate income and apply their knowledge [14,30]. However, this study has identified a higher level of HPs with formal training than that has been reported previously.

Insufficient PMTCT knowledge and poor practices by healthcare providers in informal health centers: This study found that 51% and 90% of the participants had an insufficient level of PMTCT knowledge and practices, respectively. These findings highlight concerns about the general quality of care provided by informal providers [30-32]. However, these low levels of PMTCT knowledge and practices are not unique to informal health centers. Several studies of formal health facilities in Cameroon have shown similar results. For example, one study conducted in formal health facilities revealed that only 52% and 23% of HPs had a good level of PMTCT knowledge and practices [33]. Moreover, In the study of Feudjio et al., assessing the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of PMTCT among HPs, in the childbirth rooms of district hospitals and sub-divisional medical centers in the city of Yaoundé, 49% of HPs had insufficient PMTCT knowledge and practices [34]. However, a study conducted by Penda et al. in 2014 found acceptable HP’s knowledge of PMTCT, but insufficient practices due to a lack of awareness about standard procedures [35]. The absence of PMTCT knowledge among HPs has also been reported by other research groups in sub-Saharan Africa, with about 40% of HPs in formal health facilities having poor knowledge and practice levels [36,37].

The item with the lowest score in the PMTCT knowledge section of the questionnaire related to breastfeeding for the first six months of life in HIV-exposed infants born to women on ART. Indeed, lack of knowledge about HIV-exposed infant feeding was high among our HPs. This illustrates either a lack of HP awareness about current Cameroonian guidelines on HIV and infant feeding, that promote exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life [25], or fear of mother-to-child transmission despite the mother’s ART coverage. Similar results were reported in some studies, highlighting that HIVexposed infant feeding guidelines were also misinterpreted or unknown by health workers in formal health facilities; indicating that policies related to infant feeding in the context of HIV have been poorly disseminated, resulting in poor or inadequate counseling of HIV mothers [38,39].

In this study, only 8% of HPs documented patient referrals using a completed form. Referrals were primarily verbal, consisting of a recommendation that included the name of the HIV care unit, preferably public, where the patient could ensure PMTCT care continuation. This type of general verbal referral is widely practiced by IHCs [13,14]. A review of maternal deaths at Douala General Hospital in Cameroon, found that all referrals made by IHCs were verbal and lacked documentation. This made it difficult to know what interventions were received by the patient in the IHCs [13].

Fewer than half of the HPs in the study performed HIV post-test counseling and only 15% mentioned aspects of partner involvement, by encouraging sharing status, or HIV counseling and testing proposals with a male partner. Yet studies indicate that HIV counseling and testing of the male partners of pregnant women helps to increase the use of PTMCT services [40-43]. This study identified a low level of posttest counseling and involvement of male partners, as well as a lack of psychosocial support for PWLHIV, raising concerns about appropriate continuum of PMTCT care for pregnant women who screen HIV positive in these IHCs.

Lack of formal PMTCT training and poor PMTCT knowledge and practice: The multivariable logistic model found that the lack of formal PMTCT training in the prior two years was associated with insufficient PMTCT knowledge.

Several studies in formal health facilities indicate that the low skill of HPs relating to PMTCT is caused by a lack of access to reliable and complete information [33,44]. HPs with no PMTCT experience were more likely to have inadequate knowledge about PMTCT than those with five years or more experience. This is likely because more experienced HPs had performed PMTCT activities for a longer period of time, improving their understanding and knowledge about the topic. This could also justify why HPs working in the referral model were more likely to have poor PMTCT practices.

Public health implications

Since IHCs often perform PMTCT activities with no supervision, it is critical that pregnant women received in these IHCs become targets for PMTCT program in Cameroon. Strategies to return these women to a safer healthcare circuit should be considered. Given that a low level of PMTCT knowledge and practices is reported in both informal and formal healthcare facilities, PMTCT programs would benefit from strengthening and intensifying the training and formative supervision of all staff involved in mother and child healthcare services. Training facilitates the acquisition of knowledge and formative supervision makes it possible to better fix these knowledges, and improve practices.

Limits

This study had a small sample size so is likely to have limited power. In addition, due to the unavailability of studies conducted in IHCs, this study was only able to compare PMTCT knowledge and practices to the findings of research conducted in the formal sector. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to provide an overview of the PMTCT offer in IHCs and PMTCT knowledge and practices in IHCs.

Conclusion

This study highlighted the range of supply and the density of PMTCT activities in IHCs in the cities of Douala and Ebolowa in Cameroon. The findings also revealed low levels of PMTCT knowledge and practices among HPs working in these settings. This was associated with a lack of formal PMTCT training over the prior two years. The results raise questions about the quality of mother and child care in informal healthcare centers and suggest that strategies are needed to improve the healthcare of these patients. The elimination of mother-tochild HIV transmission cannot become a reality in Cameroon without considering the activities of IHCs.

Ethical Considerations

The ECIP-PMTCT study was approved by the National Ethics Committee of Cameroon (Ethical clearance n° 2019/03/1155/CE/ CNERSH/SP) and by the Cameroonian Ministry of Public Health (Administrative authorization n° 631-15.19) before the implementation of the study. Informed and signed consent of Head of IHCs and HPs were also collected.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful all the managers of the informal health centers who allowed us to carry out this study in their structures, all their staff who take part in this study and Cédric Djadda who helped us to collect the questionnaires in the city of Douala.

References

- Lachaud JP (1989) State disengagement and labour market adjustments in French-speaking Africa.

- African Union (2008) Study on the Informal Sector in Africa. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Godlonton S, Okeke EN (2016) Does a ban on informal health providers save lives? Evidence from Malawi. J Dev Econ 118:112-132.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Musyimi CW, Mutiso VN, Ndetei DM, Unanue I, Desai D, et al. (2017) Mental health treatment in Kenya: task-sharing challenges and opportunities among informal health providers. Int J Ment Health Syst 11:45.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Somsé P, Mberyo-Yaah F, Morency P, Dubois MJ, Grésenguet G, et al. (2000) Quality of sexually transmitted disease treatments in the formal and informal sectors of Bangui, Central African Republic. Sex Transm Dis 27:458-464.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mendo E, Boidin B, Donfouet HPP (2015) The use of informal micro-care units in Yaoundé (Cameroon): determinants and perspectives. J Med Manag Eco 33:73.

[Crossref]

- National Institute of Statistics (2007) Third Cameroon Household Survey 2007.

- Geest SV (2017) Drugs in a Cameroonian market: Reconsidering the commodification and pharmaceuticalization of health. Anthropol Sante 14.

[Crossref]

- Abomo DM (2016) The burden of the fight against urban malaria in Cameroon: inventory, constraints and prospects. Canadian J Trop Geo 3:26-42.

- Socpa A (1995) Street pharmacies in the urban medical space-Emergence and determinants of informal strategies for access to medicines in Douala. Anthropol.

- Wogaing J (2010) From quest to drug consumption in Cameroon. Int J Med 3.

- Ministry of Public Health (2017) Sanitation of the health map.

- Ekane G, Mangala F, Obinchemti T, Nguefack C, Njamen T, et al. (2015) A Review of Maternal Deaths at Douala General Hospital, Cameroon: The Referral System and Other Contributing Factors. Inter J Trop Dis Health 8:124-133.

- Sieverding M, Beyeler N (2016) Integrating informal providers into a people-centered health systems approach: qualitative evidence from local health systems in rural Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res 16.

- Turan JM, Onono M, Steinfeld RL, Shade SB, Owuor K, et al. (2015) Implementation and operational research: Effects of antenatal care and hiv treatment integration on elements of the PMTCT cascade results from the SHAIP cluster-randomized controlled trial in Kenya. J Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 69:e172-e81.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Washington S, Owuor K, Turan JM, Steinfeld RL, Onono M, et al. (2015) Implementation and Operational Research: Effect of Integration of HIV Care and Treatment Into Antenatal Care Clinics on Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission and Maternal Outcomes in Nyanza, Kenya: Results From the SHAIP Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 69:e164-e71.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Psaros C, Remmert JE, Bangsberg DR, Safren SA, Smit JA (2015) Adherence to HIV care after pregnancy among women in sub-saharan africa: Falling off the cliff of the treatment cascade. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 12:1-5.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Cock KM, Fowler MG, Mercier E, de Vincenzi I, Saba J, et al. (2000) Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource-poor countries: translating research into policy and practice. JAMA 283:1175-1182.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Embree J (2005) The impact of HIV/AIDS on children in developing countries. Paediatr Child Health 10:261-263.

[PubMed]

- Gong T, Wang H, He X, Liu J, Wu Q, et al. (2018) Investigation of prevention of mother to child HIV transmission program from 2011 to 2017 in Suzhou, China. Sci Rep 8:18071.

- Kassa GM (2018) Mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection and its associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 18.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Car LT, Velthoven MHMMT, Brusamento S, Elmoniry H, Car J, et al. (2012) Integrating prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programs to improve uptake: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 7.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prendergast AJ, Essajee S, Penazzato M (2015) HIV and the millennium development goals. Arch Dis Child 100:S48-S52.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Family Health International Institute for HIV/AIDS (2003) Baseline Assessment Tools for Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) Of HIV.

- National committee for the fight against AIDS. (2019) National HIV Care Guidelines.

- Gebreselassie AF, Bekele A, Tatere HY, Wong R (2021) Assessing the knowledge, attitude and perception on workplace readiness regarding COVID-19 among health care providers in Ethiopia—An internet-based survey. PLoS One 16:e0247848. [Crossref]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- CNLS (2019) PMTCT progress report Yaoundé Cameroon.

- Bloom G, Standing H, Lucas H, Bhuiya A, Oladepo O, et al. (2011) Making health markets work better for poor people: the case of informal providers. Health Policy Plan 26:i45-i52.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Das J, Chowdhury A, Hussam R, Banerjee AV (2016) The impact of training informal health care providers in India: A randomized controlled trial. Science 354:aaf7384.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sudhinaraset M, Ingram M, Lofthouse HK, Montagu D (2013) What is the role of informal healthcare providers in developing countries? A systematic review. PLoS One 8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nkwabong E, Nguel RM, Kamgaing N, Jippe ASK (2018) Knowledge, attitudes and practices of health personnel of maternities in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a sub-Saharan African region with high transmission rate: some solutions proposed. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18:227.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fouedjio JHH, Nana AN, Tsuala JF, Ymele FF, Mbu R (2016) Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of the prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV by Providers of Delivery Rooms of District Hospitals and Medical Centers of the City of Yaoundé. Health Sci Dis 17.

- Penda CI, Ndongo FA, Bissek A-CZ-K, Téjiokem MC, Sofeu C, et al. (2019) Practices of Care to HIV-Infected Children: Current Situation in Cameroon. Clin Med Insights Pediatr 13:1179556519846110.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Temitope A, Ofili A, JUE O, Adejumo O (2017) Health Workers’ Knowledge of preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. J Com Med Primary Health Care 29:1-10.

- Arisegi S, Awosan K, Abdulsamad H, Adamu A, Isah M, et al. (2017) Knowledge and Practices Regarding Prevention of Mother-to-child Transmission of HIV among Health Workers in Primary Healthcare Centers in Sokoto, Nigeria. 6:1-9.

- World Health Organization (2019) Guideline: Updates on HIV and infant feeding. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Samburu BM, Kimiywe J, Young SL, Wekesah FM, Wanjohi MN, et al. Realities and challenges of breastfeeding policy in the context of HIV: a qualitative study on community perspectives on facilitators and barriers related to breastfeeding among HIV positive mothers in Baringo County, Kenya. Int Breastfeed J 16:39.

- Nyoni S, Sweet L, Clark J, Ward P (2019) A realist review of infant feeding counselling to increase exclusive breastfeeding by HIV-positive women in sub Saharan-Africa: what works for whom and in what contexts. BMC Public Health 19:570.

- World Health Organization (2015) WHO global strategy on people-centered and integrated health services: interim report [internet]. Geneva.

- Abuogi L, Hampanda K, Odwar T, Helova A, Odeny T, et al. (2021) HIV status disclosure patterns and male partner reactions among pregnant women with HIV on lifelong ART in Western Kenya. AIDS Care 32:858-68.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hampanda K, Helova A, Odwar T, Odeny T, Onono M, et al. (2021) Male partner involvement and successful completion of the prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission continuum of care in Kenya. Int J Gynecol Obstet 152:409-415.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chanyalew H, Girma E, Birhane T, Chanie MG (2021) Male partner involvement in HIV testing and counseling among partners of pregnant women in the Delanta District, Ethiopia. PLOS ONE 16:e0248436.

- Tchendjou Tankam PY (2014) Conseil prénatal du VIH orienté vers le couple : faisabilité et effets sur la prévention du VIH au Cameroun.

- Kufe NC, Metekoua C, Nelly M, Tumasang F, Mbu ER (2019) Retention of health care workers at health facility, trends in the retention of knowledge and correlates at 3rd year following training of health care workers on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV–National assessment. BMC Health Serv Res 19:78.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Onambele AAS, Bigna JJ, Schouame IL, Nolna SK, Socpa A (2023) Current State of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV in Informal Health Care Centers in Cameroon. J Infect Dis Ther 11:543

Copyright: © 2023 Onambele AAS, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 1625

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Apr 04, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1369

- PDF downloads: 256