Research Article Open Access

The Criminal Liability of Companies, An International Comparison: The Case of USA, UK, Spain and Italy

Carna AR*University of Milan Bicocca, Italy

- *Corresponding Author:

- Carna AR

Phd , University of Milan Bicocca Italy

Tel: +39 02 87166657

E-mail: carna@studiocarna.it

Received Date: March 09th, 2015 Accepted Date: April 29th, 2015 Published: May 13th, 2015

Citation: Carna AR (2015) The Criminal Liability of Companies, An International Comparison: The Case of USA, UK, Spain and Italy. J Civil Legal Sci 4:144. doi:10.4172/2169-0170.1000144

Copyright: © 2015 Carna AR. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Civil & Legal Sciences

Abstract

A business economist who analyzes several internal control systems implemented according to the Legislation Decree n° 231/2001 must inevitably refer to the many international laws. In effect, this is a sensitive matter and it should not be confined to the national borders. International interest is constantly increasing for many reasons, both regulatory and economic. The first reason is the transnational importance of the legislation.

Keywords

Corruption; Compliance program; Anticorruption; Internal control system; Fcpa;231/2001; Uk bribery act; Ley organica 5/2010; Anti-fraud; Compliance; Audit; Criminal

Introduction

A business economist who analyzes several internal control systems implemented according to the Legislation Decree n° 231/2001 must inevitably refer to the many international laws. In effect, this is a sensitive matter and it should not be confined to the national borders. International interest is constantly increasing for many reasons, both regulatory and economic. The first reason is the transnational importance of the legislation [1]. Another reason could be more “managerial”, more “business concerned”, and it should be semplified or summarised as “compliance’s risk globalization”.

Nowadays, we are accustomed to the globalization of markets, to the immediate migration of services and products from one side of the world to the other. Furthermore, the research of production synergies leads national companies to relocate whole or part of their production, that provides a new market, a larger market [2].

Clearly, serious risk assessment cannot separately analyze operational and compliance risks; today more than ever, fundamental drivers for long-term competitive success [3,4]. Here are some real life examples that could help us to better understand what I’m going to talk about.

In 2011, Japan was affected by a catastrophic earthquake which was followed by an escape of nuclear material from the Fukushima nuclear power plant. A pharmaceutical company has its production site in Japan and sells its products worldwide; as a prudential measure the regulatory authorities in various countries, including Italy, suspended the sale of medicines until it was confirmed that no contamination had occurred. An event took place in Japan, yet the reverberation effects were felt in most parts of the world.

In another case, a multinational chemical manufacturer had a serious workplace accident at an Italian site. In accordance with current legislation, the competent authority ordered the temporary closure of the establishment because it did not appear to comply with certain safety standards. The production stoppage caused an inability to sell their products in foreign markets, also as a result of reputation damage, the main buyer preferred to buy from the back-up manufacturer, even after the reopening of the Italian site, which, for obvious reasons had many adverse effects. A compliance risk, also relevant to the decree n° 231/2001 (the non-compliance with rules about safety in the workplace) has destabilized the corporation, not only due to the accident that occurred, but also because of the loss of an important market share.

Globalization of compliance risks imposes a serious reflection in most of the manufacturing organizations, certainly in those that operate, even if indirectly, on several markets and of course, multinational companies [5]. In order to assist the reader in this way we wish to briefly outline the main features of similar laws to our “D.lgs. 231/2001” existing in other countries, such as the United States of America, the United Kingdom and Spain.

The aim is to highlight the many points of contact and the synergies that derive in terms of risk assessment, implementation of appropriate procedural and audit/control systems as well as for subsequent monitoring. In fact, the impulse to adopt a law on the liability of companies (in Italian Legislative Decree no. 231/2001) has been given by some international Acts, such as:

• Brussels Convention of European Communities of 26 July 1995 on the Protection of Financial Interests;

• Convention of 26 May 1997, signed at Brussels for the fight against corruption involving Officials of the European Community or their Member States;

• OECD Convention of 17 September 1997 on combatting bribery of foreign public officials in international business transactions.

We want to underline that the normative approach, in all countries where it exists, is based on a basic ethical principle that must inspire and lead the action in business and management. The rules, whether they be internal or external to the company are superfluous, if there is no ethical commitment together with the example of top management: each organizational model would be ineffective to protect the organization from “criminal” liability [6,7].

It is also known, that it is not enough to declare ethic principles (unfortunately a common practice and widely abused ) rather, it is essential to actively adhere to them every day. This is relevant even more so in periods of crisis (both economic and value related) in which we find ourselves today [8].

The Federal Sentencing Guidelines and the FCPA– USA

The U.S. is, in our opinion, a pioneer in the introduction of the concept, relevant even under legal aspects, linked to the ability of companies to commit several crimes. In this regard, there is a famous judgement called “New York Central & Houston River” of 1909, according to which “if a company can level mountains, fill in valleys, build railways and have locomotives run over you, it means that it has the will to engage in these actions, and can therefore behave both wickedly and virtuously “ [9,10]. The company has both the capacity to be “technical” and “operational” and the ability to choose how to behave: wickedly or virtuously. However, the first organic formula is found in 1977 with the implementation of the Foreign Corrupt Practise Act (FCPA) which had the purpose of punishing international corruption. In 1991 the Federal Sentencing Guidelines were issued and updated in 1998 and again in 2004; the reflections below refer to the current edition [11].

Chapter Eight in the “Organizational Guidelines” of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines is dedicated to outlining company organizational profiles and the implementation criteria of the internal audit system [12]. It also provides clear guidance on the methodology underlying the determination of the sanction, known as “culpability score”, which we will discuss shortly.

We would like to stress, in particular, that the adoption of a compliance program is only a mitigating factor in the imposition of the sanction against the business entity involved in criminal proceedings [13,14]. Please note that the Legislative Decree no. 231/2001, which introduced the administrative liability of a company, in article 6 provides an exempting circumstance for those companies that have adopted and effectively implemented the organizational model and appointed by the Supervisory Bodies. Such an important differentiation requires further study.

In the U.S. experience, the so-called carrot-stick approach is the basis of the compliance program (rif.: Organizational Model), as efficiently and effectively it may seem, it cannot make the entity exempt from liability, but it can lead to a reduction of the punishment [15].

There is more. In case the crime were committed by a board member, the company will not have any mitigating factor. In Italy, in the same hypothesis, the exemption is still viable even with the reversal of the burden of proof.

According to overseas law, it is top management who has the power to control decisions and behaviour of the legal entity and, as such, no control system or procedures may limit the power of management, including - naturally - the possibility of committing “criminal”offences: hence the loss of any benefit of the compliance program. It is a hard statement but with a very clean and simple application because it is clear who are the top management subjects and their role in the compliance program.

Chapter eight also clarifies that the liability of the company is aggravated by certain circumstances:

• the involvement in or the tolerance of criminal activity,

• the prior history of the organization,

• the violation of an order,

• the obstruction of justice.

We easily understand how the U.S. legislator imposes active collaboration on business entities, both to discover illegal conduct and to partecipate in an investigation. Such conducts are the cause for mitigation of liability, as well as the existence of the compliance program: self-reporting, cooperation or the acceptance of responsibility. We must not overlook the loss of any benefit of the compliance program when the company became aware of the misconduct and failed to report the case to the competent authorities (or omitted some “detail” in the selfreporting).

We already mentioned the culpability score. The penalty is defined as a “score system”: starting from the base penalty, adding the aggravating reasons and subtracting the mitigating factors to determine the fine [16]. In our internal legal system, it is well-known that the penalty system is based on shares, defined according to the seriousness of the behaviour and the asset size of the company. “Collaboration” does not have a bearing on the normative aspect.

The U.S. law, like our own, requires that the organization should adopt codes of ethics and standards of conduct and must implement appropriate procedures, clearly structured in terms of internal controls and reasonably capable of reducing the likelihood of criminal conduct (ability to prevent criminal conduct). However, the ethical dimension is normatively valued to the extent that the organization must make every reasonable effort not to include individuals, without due reason, who have been involved in illicit affairs or have shown behaviour patterns which are certainly incompatible with the implementation of an effective compliance program [17,18].

It is a requirement of “integrity” which can be applied to all organizations, and it must be verified in a very delicate due diligence process and the possible exemption (even if really not recommended!) must be well motivated [19].

In addition, an effective control system cannot ignore the possibility for all recipients of a compliance program (employees and agents) to report, even anonymously and with a guarantee of confidentiality and protection, any conduct in violation of the rules, whether they may be attempted or potential.

This is whistleblowing, i.e. the need that “the organization shall take reasonable steps to have and publicize a system wich may include mechanism that allow for anonumity or confidentiality, whereby the organization’s employees and agents may report ... regarding potential or actual criminal conduct without fear of retaliation.

We find the same approach in the 231 System; in this the flow of information, and the ability to report the cases of violation of the 231 Model to the Supervisory Board, even if only attempted, are cardinal in the delicate process of verification of the adequacy of the model itself.

Last but not least, the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, like the Decree n° 231, impose the implementation of a system of sanctions, finalized to the punishment of misconduct, in violation of the Model, therefore to be a deterrent of “criminal behaviour”.

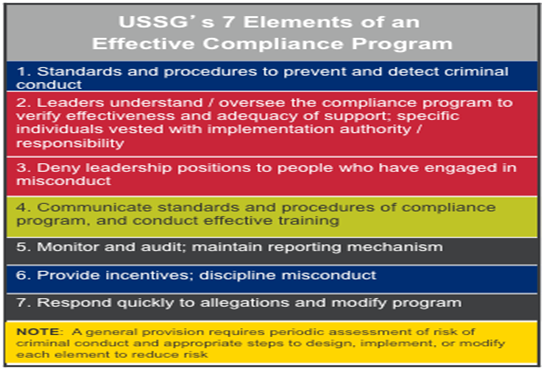

The table below summarizes the “fundamental seven elements” for the implementation of an effective compliance program (Table 1).As already mentioned, in 1977, the FCPA was enacted with the aim of preventing corruption of foreign public officials by U.S. companies (U.S. federal securities statute, 15 USC § 78dd-1 et.Seq.).

|

Table 1: Fundamental seven elements" for the implementation of an effective compliance program.

Government agencies that oversee the implementation of this system are the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The FCPA prohibits U.S. companies and their employees and agents or other persons, to give (or even offer or promise) money or other benefits to foreign public officials in order to obtain any kind of advantage of any nature [20].

Therefore, the main elements of the FCPA anti-corruption provision are: - the payment, offer or promise to pay (in cash or in kind), directly or indirectly;

- to any foreign public official;

- made with an bribery intent;

- in order to obtain or retain business;

- even if the intention may not be realized.

The FCPA provides, moreover, a number of “accounting” provisions that impose companies in scope to keep accurate accounting (books and records) and to implement adequate systems of internal control, supervising all transactions, not just those that may violate the antibribery rules. Specifically, the accounting system adopted, and the related surveys, must not only comply with the international accounting standards but also adequately describe and record in a transparent and complete manner, all the transactions of the Company or of third parties acting on behalf of it.

For instance, consider sales prices lower than the market prices. This activity should be regarded as an advantage for the buyer if he is a person, recipient of the regulations (foreign public official). The accounting system must be suitable to represent the situation outlined and to detect whether the prices are lower than market ones. Detection must also allow for the identification of the recipient.

Separate consideration must be spared for the so-called “Facilitating payments” – if they are permitted by local rules - which must be accounted for in a dedicated account and include, in the description of the operation, all the necessary elements to reconstruct both the beneficiary and purposes [21]. The “manipulating” of “books or records” to conceal or falsify operations is prohibited and subject to severe sanction.

As already mentioned, the FCPA requires companies to implement and maintain a system of internal controls designed to ensure that:

• Among other things, transactions are properly authorized: this is to ensure that decision-making should be marked by the segregation of duties to avoid concentrating management responsibilities and control in a single subject;

• Financial records and accounts are accurate for external reporting, access to assets is permitted only in accordance with management instructions, and that the books are audited at reasonable intervals.

In the FCPA system the process of accreditation of third parties plays a fundamental role. It involves the identification, not only of the age and profile sheet of the party, but also of the ethical aspect, any situation of conflict of interest (even if only potential), as well as “all relevant information for a better relationship with them”. The (Table 2) below summarizes the most severe fines imposed in the period 2005-2011 [22]. The following (Table 3) summarizes the DOJ/SEC FCPA Enforcement Actions in 2011 [23].

| Company name | Fine |

| Siemens | $800 |

| KBR/Halliburton | $579 |

| BAE | $400 |

| ENI S.p.A. | $365 |

| Technip | $338 |

| JGC Corporation | $219 |

| Daimler | $185 |

| Alcatel-Lucent | $137 |

| Panalpina | $82 |

| Johnson & Johnson | $70 |

| ABB | $58 |

| Pride International | $56 |

| Baker Hughes | $44 |

| Willbros | $32 |

| Chevron | $30 |

| Titan | $29 |

| Bridgestone | $28 |

| Vetco | $26 |

| York International | $22 |

| Statoil | $21 |

Table 2: The most severe fines imposed in the period 2005-2011.

| Diageo plc | $16.5 million settlement |

| Armor Holdings Inc. | $16 million settlement |

| Tenaris S.A. | $8.9 million settlement with deferred prosecution agreement |

| Rockwell Automation, Inc. | $2.7 million settlement for alleged violation of accounting provisions |

| Johnson & Johnson | $77 million criminal penalty and disgorgement with deferred prosecution agreement |

| Converse Technology Inc. | $2.8 million settlement for alleged violation of accounting provisions |

| JGC Corporation | $218.8 million criminal penalty with deferred prosecution agreement |

| Ball Corporation | $300,000 fine in settlement of alleged violation of accounting provisions |

| IBM | $10 million settlement for alleged violation of accounting provisions |

| Maxwell Technologies, Inc. | $13.6 million penalties and disgorgement |

| Alcatel-Lucent S.A | $137 million settlement |

| Tyson Foods, Inc. | $5.2 million criminal penalty and disgorgement |

Table 3: The DOJ/SEC FCPA Enforcement Actions in 2011.

The UK Bribery Act

In April 2010 the UK “Bribery Act 2010” was approved in (it has been in force since the 1st July 2011). It is “an Act to make provision about offences relating to bribery, and for connected purposes”. The legislation is designed in order to oppose and punish corruption, both public and private, and introduces a severe penalty system that impacts on companies [24]. In fact, section 7) of the Bribery Act says that “companies” are responsible for acts of corruption committed by their employees and “associated people” but, like the Italian legislator in the 231/2001, can be exempt from liability if they can demonstrate that it has taken “adequate procedures designed to prevent persons associated with it from undertaking a conduct that led to an act of bribery to retain/obtain business or advantages in the conduct of a business [25].”

The offence is realized when:

• Directly or indirectly, offering, promising or giving, or requesting, agreeing to receive or accepting a financial or other advantage, to/from another person, intending the advantage to induce or reward someone for performing a relevant function improperly [26].

Therefore, “a company is criminally liable for the actions of associated people who, during activities on behalf of the same company, commit the crime of corruption in order to obtain or retain benefits for the business or affairs of the society itself [27].” The “bribery of Foreign Public Officials (FPO)” is the violation that occurs “directly or indirectly, offering, promising or giving a financial or other advantage, intending to influence an FPO in his capacity as an FPO, with the intention of obtaining or retaining business or a business advantage.”

The scope of the legislation is very broad and transnational. The Act provides that “offense is committed if either:

- any act/omission which forms part of the offense takes place in the UK, or

- no act/omission took place in the UK, but the person has a close connection with the UK.”

The concept of relevant commercial organization includes both UK companies and all companies that have a “business or part of a business in the UK.” The law requires a very large application which cannot be limited within national borders. On this point, the thought of R. Alderman, Director of Serius-Fraud Office SFO, governing body for investigations, is very clear, according to which he states “don’t rely on a very technical approach to the Bribery Act to try and persuade yourself that you’re outside the scope of the Act. The safe working assumption is that if you have got a UK presence in one way or another then you are within the scope of the Bribery Act. Don’t take the risk of thinking we have this clever interpretation by clever lawyers that tells us we are outside and therefore we are free to carry on bribing. That’s very unsafe”. The Act and subsequent regulations determine the implementation of appropriate procedures and, with them, aspire to an exemption from liability in the event of an “accident.” Specifically, the criteria for the implementation of adequate procedures to prevent corruptive phenomena are summarized in the following principles:

1. Risk assessment - identify and understand the specific risk as well as the ways in which it could be realized;

2. Top level commitment - the procedural system must come from the top management who is responsible for the effective implementation and control;

3. Due diligence - verification of counterparties in relation to both objective and subjective requirements and consistent management of “red flag” and periodic review of accreditation;

4. Clear, practical and accessible polices and procedures - the procedural system must be spread, recipients adequately trained and able to obtain all the necessary information, and the procedures must be clear and easily applicable;

5. Effective implementation - is not to create documents, on the contrary it is necessary that the conduct of the recipients of the legislation be consistent with the rules and illegal behaviour be punished;

6. Monitoring and review - Periodic monitoring is designed to verify the correctness of the system, the underlying behaviour and the possible need for revision.

The points just sketched, although with understandable differences, are methodologically similar to what is provided by U.S. and Italian legislators. In fact, in “our” case law 231/2001 does not provide clear indications in this regard and the judgment of the adequacy of the Model is referred to the dialectics and the outcome of the legal proceedings [28].

However, it is unthinkable to implement a Model 231 that aspires to adequacy without following the above steps. Unfortunately, for us it is just “best practices” which does not follow “coverage” legislation. Suggestions of similar content can be derived from the Confindustria Guidelines and the confirmation that “the Model 231 or the appropriate procedures in order to exercise its preventive effect, must be constucted in such a way to take into account the characteristics of the business entity of the economic, organizational complexity the geographical area. in which it operates [29].” A reflection on the “sanctions” may be useful both in terms of individuals and companies. In particular, “the Act raises the maximum imprisonment from 7 years to 10 years for an individual” and “a company convicted of failing to precautionally prevent bribery could receive an unlimited fine, debarment from public contracts under the Public Contracts Regulations 2006 (but corporate offense will not result in mandatory debarment) (for) related money laundering offences [30].” Although this is not information relating to the application of the Bribery Act, the following data is useful in order to understand the current trend in UK (Tables 4 and 5).

| Date | Company | Punishment | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oct 08 | Balfour Beatty | Civil recovery | £2.25 m |

| Jan 09 | AON Ltd | FSA fine | £5.52 m |

| Sept 09 | Mabey & Johnson | Fine/Confiscation | £6.6 m |

| Oct 09 | AMEC | Civil recovery | £5 m |

| March 10 | Innospec Ltd | Fine | $12.7 m ($40m global) |

| Dec 10 | BAE | Fine/Voluntary | £500K fine / £30 m |

| Feb 11 | MW Kellogg | Civil recovery | £7 m |

| Apr 11 | De Puy International | Civil recovery | £4.9 m |

| July 11 | Willis | FSA fine | £6.9 m |

| July 11 | Macmillan | Civil recovery | £11.3 m |

Table 4: Application of the Bribery Act for companies.

| Date | Company | Punishment | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oct 07 | IKEA staff and supplier | Imprisonment | 1-3 years |

| Sept 08 | MD of CBRN Team Ltd | Imprisonment | 12 months |

| Oct 08 | Georgiou Nicholas | Imprisonment | 6 months |

| Apr 10 | Mr Dougall | Imprisonment | 12 months (suspended) |

| Oct 10 | Director of PWS International | Imprisonment | 21 onths |

Table 5: Application of the Bribery Act for individuals.

The Ley Organica 5/2010 - Spain

On 23 June 2010, Spain adopted the Ley Organica n. 5 (it has been in force since 23 December 2010) through which “se regula responsabilidad penal de las persona juridicas [31].” The law changed the existing Criminal Code by introducing art. 31 bis, which provides, among other things, that the criminal liability of legal entities may be activated given the following conditions [32]:

1. That “se haya cometido uno de los delitos previstos” – the offence;

2. That “ese delito se haya cometido en nombre o por cuenta, y ademas en su provencho, de una persona juridica” – interest or advantage;

3. That “se haya cometido por su administrador de hecho o de derecho o por su representante legal” – senior management [33];

4. “o por cualquier otro empleado sometido a la autoridad de los anteriores” - employees.

The legislation applies to all legal entities with the exception of “exclusions” at the article 31 bis, paragraph 5 (State, Public Institutions, Public Companies, Political Parties, Trade Unions, etc.) [34] Since the formulation the similarities with the 231/2001 have been clear. As in Italy, the conditions for the activation of the process of “criminal” liability by the company are both the committing (even if attempted) of an offense by a board member or employee as well as the interest or resulting advantage for the Legal Entity [35].

Similarly, in Spain we see the development of a “Manual de Procedimiento, Normas de Conducta o Protocolos de cumplimento, correctamente elaborados con concretas labores de control” which becomes essential to aspire to, in order to avoid liability for legal entities [36]. In other words, it is the implementation of a sort of Organizational Model, which is not a mere phenomenon of corporate bureaucracy. Conversely, computing tasks and underlying control activities should be transparent. The possibility of reversing the “carga de la prueba”, is also significant, since at the moment of the occurrence of the crime the legal entity “va a responder de forma automatica”: attention to the exemption of liability shall be the task of those who have implemented procedures, controlled and suggested corrective actions and/or fines as well as the circumvention of procedures by those who committed the crime. Furthermore, in accordance with art. 31 bis, paragraph 4, letter. d, a mitigation is provided in the case that “cometido ya el Delito, se adopten por la empresa eficaces medidas para prevenir en el futuro nuevos delitos”: this aspect is very similar to “our” remedial model or post factum. The very strict fines are specified at the art. 33.7 [37]

- Multa por cuotas o proporcional;

- Disolución de la persona jurídica. La disolución producirá la pérdida definitiva de su personalidad jurídica, así como la de su capacidad de actuar de cualquier modo en el tráfico jurídico, o llevar a cabo cualquier clase de actividad, aunque sea lícita;

- Suspensión de sus actividades por un plazo que no podrá exceder de cinco años;

- Clausura de sus locales y establecimientos por un plazo que no podrá exceder de cinco años;

- Prohibición de realizar en el futuro las actividades en cuyo ejercicio se haya come- tido, favorecido o encubierto el delito. Esta prohibición podrá ser temporal o definitiva. Si fuere temporal, el plazo no podrá exceder de quince años;

- Inhabilitación para obtener subvenciones y ayudas públicas, para contratar con el sector público y para gozar de beneficios e incentivos fiscales o de la Seguridad Social, por un plazo que no podrá exceder de quince años;

Intervención judicial para salvaguardar los derechos de los trabajadores o de los acreedores por el tiempo que se estime necesario, que no podrá exceder de cinco años. Earlier we said that the activation of the responsibility for the Entity requires that you have or attempted a “relevant crime”.

The audience of the relevant crimes is very similar to that currently provided as a result of subsequent additions (sino all’art. 25 duodecies), by 231/2001. In Spain the advantage is, that since the entry in force of the law, operators could count on a well defined range of crimes, complete and in line with the European Community agreements, also signed by Italy. The relevant crimes of ley organica n. 5/2010 are: [38]

• Tráfico ilegal de órganos (art. 156 bis)

• Trata de seres humanos (art. 177 bis 7)

• Delitos relativos a la prostitución y corrupción de menores (art. 189 bis)

• Delitos contra la intimidad y allanamiento informático (art. 197.3 segundo párrafo)

• Estafas y fraudes (art. 251 bis)

• Insolvencias punibles (art. 261 bis)

• Daños informáticos (art. 264.4)

• Delitos contra la propiedad intelectual e industrial, el mercado, los consumidores y la corrupción entre particulares (art. 288.1 en relación con arts. 270 a 286 bis)

• Blanqueo de capitales (art. 302.2)

• Delitos contra la Hacienda Pública y la Seguridad Social (art. 310 bis)

• Delitos contra los derechos de los ciudadanos extranjeros (art. 318 bis 4)

• Delitos contra la ordenación del territorio y el urbanismo (art. 319.4)

• Delitos contra el medio ambiente (arts. 327 y 328.6)

• Delitos relativos a los materiales y radiaciones ionizantes (art. 343.3)

• Delitos de riesgo por explosivos y otros agentes susceptibles de causar estragos, así como delitos relativos a sustancias destructoras del ozono (art. 348.3)

• Delitos contra la salud pública: tráfico de drogas (art. 369 bis)

• Falsificación de medios de pago (art. 399 bis)

• Cohecho (art. 427.2)

• Tráfico de influencias (art. 430)

• Corrupción en las transacciones comerciales internacionales (art. 445.2)

• Organizaciones y grupos criminales (art. 570 quater)

• Financiación del terrorismo (art. 576 bis 2)

Conclusion

What I have outlined above reveals the common thread that characterizes the legislation we are looking at. The similarities include both general regulatory framework (this is due to the shared source) and criterias and methodology behind the implementation of appropriate systems of internal control (whether declined in terms of: adequate procedures, organisational models, procedure manuals, etc.).

The methodical ratio is that the framework is not the “bureaucratic scope” but the “correct result” of the need to protect the company’s integrity from deviant behavior by the diverse categories of people who act in the name and on behalf of the same entity. Therefore, we can not assume to “create” an adequate model without considering the local specificity as well as the specific type of risk exposure to which the entity is actually exposed.

As we have seen, the risks involved must be analyzed while referring to the “geographc” profiles since the location of any event can be very far from the area of the manifestation of the impact and vice versa.

The delicate stage of risk assessment, aimed at understanding the actual risk profile to be managed, especially in this new perspective takes on a constitutive value of all future activities. We cannot limit ourselves to only test the sensitive activities and “internal” instrumental processes in the company, we must also consider a broader horizon and the specific provisions of international regulations, in line with the markets (including financial ones, not necessarily physical) and/or the actual relations of the organization. The task is unnegotiable for multinational organizations where, however, the perspective changes - even a lot - depending on if it is the “parent” of the legal entity or the local entity itself. The position of the “parent company” seems, on appearance, to be more complicated. In fact the group policy should respond to the compliance needs, adapting to the different local regulations but their variation cannot “immobilize” the operations of the entire group.

It creates, therefore, a dialectic, an arbitrage: on the one hand a “globalized” normative profile, on the other the need to “lock down” and control, the behavior of subsidiares.

Indeed, this presents a very complex exercise, since the solution is often a compromise, a harbinger of potential significant risk, both locally and globally.

How can this risk be mitigated? Recognizing to subsidiares the real possibility to intervene in the process, in order to adapt it to stricter regulations, if any, or to local circumstances. But it may not be enough. It is essential, in fact, that local management is “trained” and “encouraged” to rise to and effectively lead this challenge. Alternative routes, which are not integrated, lead to poor performance by creating “parallel worlds” very different from each other and not very effective in the prevention of compliance risks.

The perspective of the local legal entity must be complementary:it should not passively “suffer” group decisions and without a clear moment of critical analysis, adopt the procedures given from above. This debasement of autonomy could result in a judgment of inadequacy of the principals of internal control in accordance with local regulations. It’s well known that it is not a simple approach; it is very complex for the group to share local needs. It is therefore necessary to apply greater effort at a local level, in order to be able to “prove” that you are indeed not passive parts of a process, rather, more in possession of skills and capacities to address and effectively control local behavior.

Even in this case the training of local management is indispensable. The whole process has to be contained in a virtuous organization that allows a constant level of adequacy and effectiveness of the implemented control tools.

References

- Pistorelli L (2011)Problematic aspects of the international responsibility of legal entities for crimes committed in their interest or advantage, the administrative liability of companies and institutions.

- SaitaM,Saracino P (2004)Innovation in public administration for the competitiveness of SMEs, Giuffre.

- Carnà AR (2011)the prevention of corporate fraud in the conference “Illicit Disputes And Companies - Accountancy investigations, business fraud inquiries and legal support", LIUC University,Castellanza.

- Poddighe F (2001)the company in the institutional phase, Edizioni Plus, Pisa

- Di Carlo E (2006)Governance, finance and conflict of interest in the business groups, Arachne , Rome.

- Carnà AR (2008)The Organisation, Management and Control in the management of conflicts of interest of multinational companies, the administrative liability of the Company and the entities 3: 165.

- Coda V (1982)The tension towards objectives of economic efficiency , in the determination Del income in companies of our time in the light of the thought of Gino Zappa, Cedam, Padua .

- Giovanni M (1993)Garegnani, Business ethics and responsibility of crime. From the US experience to “organizational models of management and control”, Giuffrè, Milan, 2008. Reiterated by Vittorio Coda, in Codes of ethics and liberation of the economy, ISVI.

- U.S. Supreme Court, New York Central and Hudson River Railroad Company vs United States, No. 57, Argued: December 14, 15, 16, 1908 Decided: February 23, 1909, n. 212, U.S. 481

- Garegnani GM (2009)the derivation of the standard compliance programs from the US "Derivation of norms from US compliance programs ", conference on "The criminal responsibility of community institutions in the light of Legislative Decree N., Rimini.

- Savini IA, Calleri M (2010)Federal Sentencing Guidelines American and Italian law : the recent trends in comparison , the administrative liability of companies and institutions.

- Nagel I, Swenson W (1993) The Federal Sentencing Guidelines of corporations: their development. Theoretical underpinnings and some thoughts about their future, Washington University Law Quarterly Review205-219.

- Walker R (2008)The evolution of the law of corporate compliance in United States: a brief overview, Practising Law institute, Advanced Corporate ComplianceWorkshop, 22; Gian Maria Garegnani, op.cit.85

- In our opinion, this represents a kind of “indirect” exemption, referable to the different practice obligations of criminal acts in the US with respect to the Italian counterpart. For further reading, see, amongst others, Gian Maria Garegnani, op.cit.84.

- Giovanni Maria Garegnani, Business ethics and responsibility of crime. From the US experience to “organizational models of management and control,Giuffre , Milan.

- Hasnas reveals that the culpability score “can reduce the organization’sfine by 95% or increase it by 400%”, J. Hasnas, Ethics and the problem of white collar crime, American University Law Review 54-618.

- The legislation states that “the organization shall use reasonable efforts not to include within the substantial authoritypersonnel of the organization any individual whom the organization knew, or shouldhave known through the exercise of due diligence, has engaged in illegal activities or other conduct inconsistent with an effective compliance and ethics program”.

- Savini e Calleri highlights the wish to implement a compliance program in the business entity, which allows it to develop an ever increasing sensibility towards business ethics, in an organization that promotes a company culture and that encourages the adoption of ethicalbehavior and compliance with complete regard to current legislation”, I.A. Savini, M. Calleri, op.cit., 2010 p: 77.

- Consider the case where a specific professional skill is required and the individual chosen has been involved in illicit conduct. The company must disclose this circumstance during the decisional process.

- In the exception “foreign public officials” include political parties, their officials, candidates to public offices, and the like. In particular it includes any officer or employee of.

- Mitchell (2003) The Sarbanes Oxley Act and the reinvention of corporate governance, in Villanova Law Review 48: 1189.

- McNulty P (2011) Focus on FCPA: Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Key Points for Italian and MultinationalCompanies, Baker&McKenzie, Milano.

- Paul McNulty P (2011) Focus on FCPA: Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Key Points for Italian and MultinationalCompanies, Baker&McKenzie, Milano.

- Savini IA, de Gioia-Carabellese P (2011)The "231" in the United Kingdom: a comparative reflections on the cd. omidicio corporate (corporate manslaughter) and the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 , the administrative liability of companies and institutions .

- Saita M (2006)The fundamentals of the economy and corporate strategy , Giuffre , Milan

- Even in the Bribery Act, like in the case of the US and Italy, the concept of “other advantages” for which“Corruption” does not exclusively manifest itself through the gift of monies but via concessions of other advantages which improperly coerce and redirect business practices, both public and private.

- Moretti M, Monterisi M, Belfiore G (2010)The discipline of corporate liability in UK: application profiles and extraterritoriality of the bribery act. The impact on Italian companies operates in the UK and the British companies operating in Italy, the administrative liability of companies and institutions, 1/2012, 75.

- Carnà AR, ModelloIL (2011) 231 which tool to the UK Bribery Act compliance. An integrated approach in the UK Bribery Act and Decree No. 231/2001 , International Business , Media Fiera Milano , Milan .

- Tresoldi A, Lungaro E (2011)The entry into force of the UK Bribery Act . A comparison between the guideline and British guidelines Confederation for the implementation of Legislative Decree no. 231/2001, the administrative liability of companies and institutions 117.

- Mann S (2011) The UK Bribery Act, its Extraterritorial Reach, its Relevance for Italian Companies and Recent Enforcement Trends, Baker&McKenzie, Milano.

- Sánchez F (2011)Criminal liability of legal persons, studies on reforms of the Criminal Code operates das by LO5 / 2010 of 22 June and 3/2011 of January 28, dir. Diaz - Maroto and Villarejo ,CizurMenor, 66 .

- NJ, Mata Barranco d (2011) criminal of corporations law, gennaio.

- Delacuesta JL (2012)Criminal liability of legal persons in the Spanish Law, DirittoPenale Contemporary 1-15.

- Those excluded from the sphere of application of the legislation are: “Entities of public law,assimilated : in particular, the State, local government and institutional , regulatory agencies , and international organizations under public law; State commercial entities: agencies and public companies, organizations exercising public or administrative powers of sovereignty , state corporations running public policies or provide services of general economic interest ; Political parties and trade unions " art. 31 bus, comma 5.

- Carnà AR (2012) Strengthening of anti-corruption policies and adjustments in the plans of compliance at the Conference for Anticorruption and new systems of corporate governance,Fiera Milano International- Business Media, Milan.

- Mateu-M. Prats C (2010) Criminal liability of legal persons, comments to the criminal reform, dir. by Alvarez García- González Cussac, Valencia.

- Specifically " in this area a catalog of tax penalties are specific to legal persons, adding regarding called far -effects (dissolution, suspension of activities, closure of establishments) the quotas and proportional penalty and disqualification for subsidies and support, to engage with government and to enjoy tax benefits and incentives or Social Security, " by NJ de la Mata Barranco, the criminal liability of corporations, law, 2011.

- Cuesta JL (2012)Criminal liability of legal persons in the Spanish Law, Criminal Law Contemporary 1-21.

Relevant Topics

- Civil and Political Rights

- Common Law and Equity

- Conflict of Laws

- Constitutional Rights

- Corporate Law

- Criminal Law

- Cyber Law

- Human Rights Law

- Intellectual Property Law

- International public law

- Judicial Activism

- Jurisprudence

- Justice Studies

- Law

- Law and the Humanities

- Legal Philosophy

- Legal Rights

- Social and Cultural Rights

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 17467

- [From(publication date):

July-2015 - Jul 12, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 12697

- PDF downloads : 4770