Systematic Review of School-Based Mental Health Intervention among Primary School Children

Received: 30-Jan-2018 / Accepted Date: 16-Feb-2018 / Published Date: 19-Feb-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000589

Abstract

Mental health disorders among children are increasing in trend. Evidence had suggested a better outcome if any school intervention introduced at primary school before entering the secondary level due to the peer influence. Many focused interventions on mental health targeting the school children are conducted in high income countries. Scares publication related to child mental health intervention from developing countries. This study aimed to systematically review and identify universal mental health program done in addressing the common types of mental health disorders among primary school children looking at the effectiveness of the school-based mental health intervention implemented. PubMed, Scopus, Google scholar and grey literature from these database were search using specific keywords search. Abstracts and full articles were reviewed and graded for quality in pairs using criteria determined in consensus. Any dispute was resolved through third reviewer. A total of 109,242 were found in first hit, and nine studies were included following careful selection process. Three were randomized controlled trials; two used bifactorial design, one prospective intervention cohort, one experimental design with waitlist control, one quasiexperimental pre-post and one non-equivalent group comparison with pre and post-test. Eight of 9 studies showed effectiveness in the outcome. The studies had low to moderate quality. An intervention design that adapted to the population socio cultural showed better acceptance and effective in preventing childhood mental health problems at primary school level.

Keywords: Health intervention; School based; Mental health; School children; Effectiveness

Introduction

Child mental health is one of public challenges related to the ability of a child to learn, behave or handle their emotions [1]. There is an association between mental health problems during childhood and psychiatric disorders through youth and adulthood [2]. In a recent study in 2017 involving 6,245 children aged 6 to 11 years old in Europe, it was found that more than one fifth of them have at least one mental disorder [3]. Prevalence of internalizing and externalizing mental disorders were 18.4% and 7.8% respectively [4]. The common child mental health disorders can be categorized as anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, mood disorders (primarily depression), and disruptive behavioral disorders [5]. They are not mutually exclusive and most often the children can have symptoms and problems that covers across the boundaries [5]. The causes to these issues are multifactorial ranging from individual to community attributes [3,6-7].

Mental health issues among children and adolescents in Malaysia showed an increasing trend from 13.0% in 1996 to 19.4% and 20.0% in 2006 and 2011 respectively [8]. According to the recent data published in the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2015 by Ministry of Health, the general prevalence of mental health issues among children was 12.1% [9]. The highest prevalence mental health problems among Malaysian children was due to peer problem (32.5%) followed by conduct problems (16.7%), emotional problems (15.7%), pro-social skill (11.2%) and hyperactivity (4.6%) [9]. This was based on the data collected among 5,182 children aged 5 to 15-year-old all over Malaysia.

Although these numbers seem alarming, it has to be noted that the national survey was only screening for mental health issues and not diagnosed children with mental health issues. Therefore, it may constitute a smaller proportion among the population with diagnosis were carried out together. Despite this, the prevalence of mental health problems among the children is still high and need risk reduction intervention.

Currently, there is a paucity of universal school-based mental health intervention programme in primary schools in Malaysia. The available programmes such as young doctor program called Doktor Muda [10] covers mental health superficially. It has been implemented since 1989 as school initiatives and later become an important co-curriculum school club in all primary school since year 2000 as a national health promotion strategy under collaboration of Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education Malaysia [10]. Mental health issues at primary schools are typically handled on an ad hoc basis by teachers. It has not yet one of the key modules under program Doktor muda.

Mental health problems detected during health screening by the visited school health team under the Ministry of Health will be referred to school counsellors; whose services has been established in primary schools since 1963 [11]. The school health program manages to identify and intervene mental health problems among students, but to a limited degree. This model for mental health issues intervention in primary school in Malaysia was deemed unpopular, lacked collaboration among various educational and health stakeholders, and had caused resources to not be utilized optimally [11].

The school teachers may play a part in preventing mental health issues among primary school students. A systematic review which covered 49 studies concluded that teachers hold an important role as team members with school mental health professionals like psychologists [12].

They may also serve as the sole providers to deliver school mental health interventions, which was the case in almost one fifth (18.4%) of the studies [12]. However, teachers’ roles should be limited to prevention and early identification of mental health problems rather than providers of therapeutic interventions to students already diagnosed with a mental health condition [13].

Despite, teachers may still have a role in identifying students with risks of mental health issues like anxiety and provide some measure of intervention. Collins et al. conducted and interventional study in Scotland where cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) was used to improve coping strategy and reduce anxiety among primary school students [14]. It was found that there was no significant difference between the teacher-led and psychologist-led groups (p<0.05) [14].

Other forms of intervention can also be incorporated by the teachers, for example to prevent the incidence of bullying and disorders of conduct. Some of the mental health intervention modalities include classroom-based drama, using media such as video re-enactments, and targeting peer-group behaviours to inculcate positive bystander behaviour which ultimately results in bystander intervention to mitigate individual bullying [15].

Since there is increment in the prevalence of the mental health issues among younger population and dissimilar of characteristic from adults or adolescents, a universal mental health interventional program that caters children in primary school are critical to allow early recognition of mental health issues on their own primarily as well as by their teachers or parents. The program is also needed to introduce simple coping skill and behavioural therapy in managing their own problems or symptoms. There might be a variety of intervention approaches toward the same child mental health issue, but the best method or approach to cater to this specific population in order to obtain the optimal outcome is still unknown, at least in the local context. Hence, the objective of this review is to identify universal mental health program done in addressing the common types of mental health disorders among general primary school children. It aimed to determine the effectiveness of the universal school-based mental health intervention programs that had been conducted for primary school children in improving their mental health status.

Universal school-based mental health in present study is defined as any intervention conducted at primary school focused on improving mental health status of the primary pupils in risk prevention. The intervention should generalised to mental health problems and not specifically focus on specific mental disease.

Methods

An electronic search of the following databases was done: PubMed, Scopus, Google scholar and grey literature (Library database of theses done in Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM)).

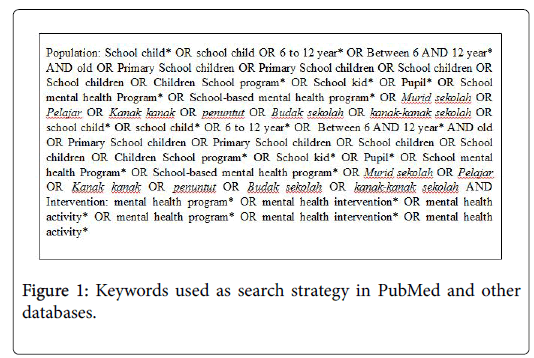

Each database was assigned to one research team member who was responsible to search according to the agreed search strategy and remove any duplicates identified. The search strategy, using PICO [16] as guideline used these specific keywords for PubMed (Figure 1).

Scopus and Google scholar used the same keywords but adapted them depending on the search engine suitability.

These lists (grey literature) was retrieved from the university library webpage and screened manually as it does not have an electronic database. Eligibility criteria was set to articles published within past 5 years (2012-2017); written either in English or Malay language; original article using any study design except for systematic review and meta-analysis.

Selection

Before the selection, each reviewer was given a code as his/her identification. Reviewers were paired up based on experience in doing systematic review. Reviewer with less or no experience doing systematic review was paired with one who had had exposure either through conducting a systematic review, involved in conducting or had attended any systematic review workshop.

Selection of articles were conducted in two stages by a pair of reviewer for each stage. In the first stage, reviewers independently screened the list of titles and abstracts for inclusion following the eligibility criteria. Any potential studies identified will be coded as “Y for Yes”.

Any disagreement between the two reviewers were resolved by third reviewer. In the second stage, the full-text articles retrieved was screened independently by the same pair of reviewers.

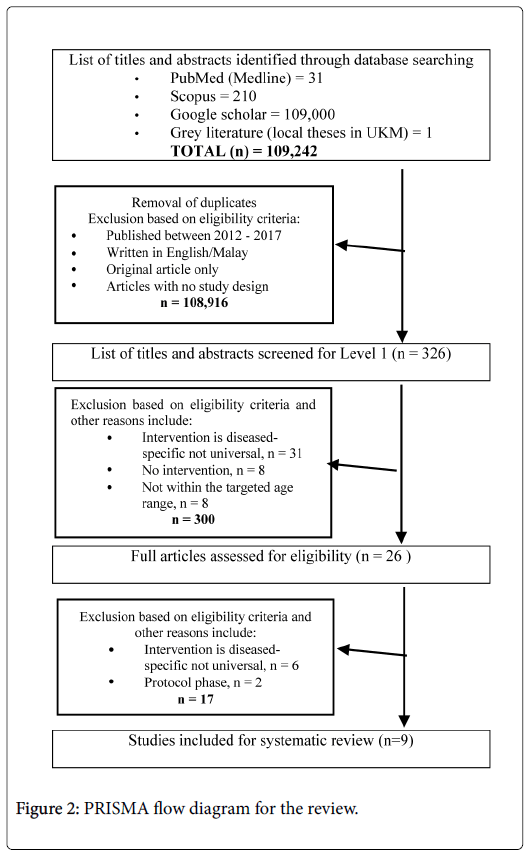

Eligibility criteria and study objectives were strictly followed for inclusion of study. Reasons for exclusion were noted down in the online Excel sheet provided. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with third author. The selection process of this review is as in the PRISMA flow diagram as described in (Figure 2).

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by the reviewer. Data extracted include name of authors, title of the study and year the article published; methods which are study design, study location, study setting and withdrawals; participants characteristics which are the total number included (N), mean age or age range, ethnicity, gender, diagnostic criteria if applicable, inclusion and exclusion criteria; Interventions which are description of the intervention, comparison, duration as well as content of both intervention and control condition and outcome of the study that were description of primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected and at which time points reported. The extracted data were reviewed by the primary author and counter-checked for accuracy and completeness by comparing with the study reports. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by involving a third person.

Results

The initial search yielded 109,242 articles in which 31 from PubMed; 210 from Scopus, 109,000 from Google Scholar and 1 from list of local theses done in UKM library. After the initial screening, 326 were accepted for title and abstract eligibility screening. From this, 26 advanced to full article screening, and 9 were accepted. The 9 studies were the basis for the descriptive aspect of this review.

Study characteristics

A total of 9 articles found and were assessed thoroughly of its effectiveness based on its intervention objectives of universal schoolbased mental health intervention program. Three (3) were randomized controlled trials; two (2) 2 × 2 bifactorial design, one (1) prospective intervention cohort, one (1) experimental design with waitlist control, one (1) quasi-experimental pre-post and one (1) non-equivalent group comparison with pre and post-test. The duration of interventions ranges from 6 weeks to 3 years with three studies not stating the duration of intervention done.

Study location and sample size

The articles included in present review originated mainly from European region (6), two were from America and one from Asia. The number of samples for the study ranges from 42 till 532 respondents.

Recruitment, withdrawal and quality of study

Most of the studies reported conveniently recruiting the school except for one study in Greece, where random selection was done throughout the sampling process. Of the 9 studies, only two stated there were no withdrawals, five studies had stated withdrawal and two do not mention regarding withdrawn respondents. The main reason for the withdrawal was due to the missing of data and respondent was not available during post-test.

Description of the intervention

Almost all interventions were grounded on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approach targeting in developing social and emotional competence. The ‘Up’ was a mental health promoting program targeted at the students, parents, school staff and health ambassador [17]. The study aimed in promoting mental health using whole school approach [18]. Two studies used mindfulness practice, aiming to regulate stress, giving effect on mental wellbeing and mental health. The intervention was named ‘Mindful Kids’ [19] and ‘Mind Up’ [20]. Another study in Korea used mind subtraction approach, which is a form of meditation which targeted in managing depression, social anxiety and aggression [21]. All interventions had skill development as building capacity in helping the respondents. There were two studies aiming for the school implementer [22,23] and six studies focused on the pupils’ skill development [14,19-21,24,25]. While there is a study [17] aiming at both the teacher as the implementer and pupils. The full description of the intervention is as in (Table 1).

| NO | Authors (year published) | Title of article | Name of intervention | Intervention summary* | Objective | Intervention duration | Evaluation tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Karasimopoulou et al.[24] | Children’s perceptions about their health-related quality of life: effects of a health education–social skills program | Skills for primary school children | Group games, theatrical, role play, discussion, moving games, poster creation, interview, brainstorm, action plan. | To grow personal skills and confidence | Done during ‘Flexible Zone’ in a 45min lesson once a week for 23 weeks. | Kidscreen-52 questionnaire |

| 2 | Collins, et al. [14] | Effects on coping skills and anxiety of a universal school-based mental health intervention delivered in Scottish primary schools | None | CBT grounded - progressive series of skills practice using interactive teaching methods, including whole class, group, and individual tasks. | Guiding children to recognize own emotional symptoms, to reduce avoidance coping strategies and to focus on proactive means of problem solving and seeking support. | 10 lessons intervention, to complete min 7 | Coping strategy indicator Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale |

| 3 | Reichl et al. [20] | Enhancing Cognitive and Social–Emotional Development Through a Simple-to-Administer Mindfulness-Based School Program for Elementary School Children: A Randomized Controlled Trail | Mind Up Program | Core mindfulness practice (every day for 3 minutes; three times a day) focusing on one’s breathing and attentive listening to a single resonant sound. Promote social and emotional learning (SEL) program | Improve Executive Functions, stress regulation, social –emotional competence, and school achievement | 4/12 interventions in 12 weeks (12 Lessons once a week, each lesson 40-50 min) | Multiple validated tool inclusive salivary cortisol level |

| 4 | Yoo et al. [21] | The Effects of Mind Subtraction Meditation on Depression, Social Anxiety, Aggression, and Salivary Cortisol Levels of Elementary School Children in South Korea | Mind Subtraction Meditation | Meditation program (Mind subtraction) sessions by certified instructor | Change perceptions and attitudes of acceptance toward situations, and reduce negative emotions | 4 times/week; 30 minutes per session, for 8 weeks. | Multiple validated tool inclusive salivary cortisol level |

| 5 | Opre et al. [22] | Empirical support for self-kit: a rational emotive education program | SELF-KIT programme (Social Emotional Learning Facilitator Kit) | Rational Emotive and Behavioural preventive programmes – targets 8 dysfunctional negative emotions – using story character to teach rational thinking and explain how rational thoughts change the way student feels and behaves. | Prevent/remit socio-emotional and behavioral problems with school-children in the lower grades | 2hour/week for 10 weeks | Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA): set of questionnaires |

| 6 | Nielsen et al. [17] | Promotion of social and emotional competence: Experiences from a mental health intervention applying a whole school approach | Up | Based on didactic model IVAC. Materials were designed to promote four key components of social and emotional competence: knowledge, skills, meaning and social action. Other aspects of the package includes educational materials and training for teachers, educational materials for parents and initiatives to be done at school levels to support the same vision. | Intervention that promotes mental health using whole school approach | Not stated | Index |

| 7 | Usera et al. [25] | The Efficacy of an American Indian Culturally-Based Risk Prevention Program for Upper Elementary School Youth Residing on the Northern Plains Reservations | Lakota Circles of Hope | Culturally-based LCH curriculum lies on the four Lakota values -generosity, fortitude (courage), wisdom, and respect. Chemical substance, alcohol, and tobacco prevention program were taught annually - 10-lesson per year curriculum on making healthy decisions | Encourage healthy decisions making on substance use, conflict resolution, communication, self-identity, and cultural competence | 3 years | Questionnaire |

| 8 | Van De Weijer-Bergsma et al. [19] | The Effectiveness of a School-Based Mindfulness Training as a program to prevent stress in Elementary School Children | Mindful Kids | Mindfulness training - meditation practices focusing on non-judging awareness of sounds, bodily sensations, the breath, thoughts, and emotions. | Investigate the effectiveness of an elementary school-based mindfulness intervention incorporated at class level | 6 weeks | Multiple validated tools |

| 9 | Cappella et al. [23] | Teacher Consultation and Coaching Within Mental Health Practice: Classroom and Child Effects in Urban Elementary Schools | BRIDGE | BRIDGE – based on other two programmes – Links to Learning my teaching Partner Consulting and coaching Intervention embedded into the regular activities of mental health professionals in urban schools | Change in classroom emotional support | Not stated | Mixed method standardized tools |

Table 1: Summary of study interventions characteristics.

Intervention outcome

Seven studies adopted validated tools to measure their outcomes. One developed index and another one developed questionnaire. This can be referred in (Table 1). Multiple outcomes were used to measure different aspects of the study. Each measurement was very objectiveorientated. Some of the outcome measured were behavioral change such as anxiety score, skill change such as avoidance and problem solving skill as well as salivary cortisol level (as proxy measure for aggressiveness).

Association

The direction of association of the intervention whether they showed significant improvement (E) or Not Significant (NS) and outcome were matched to show number of study that proven having some effectiveness. The division is based on the common mental disorders among the children. The summary of the association found in the study is shown in (Table 2).

| Common mental disorder among children* | Direction of association | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorders | E | 1/9 (11.11%) |

| Schizophrenia | No study targeting this topic | |

| Mood disorders | E | 1/9 (11.11%) |

| NS | 1/9 (11.11%) | |

| Disruptive behavioural disorders | E | 2/9 (22.22%) |

| Mix** | E | 4/9 (44.44%) |

| *E: Result showed improvement following intervention even though the improvement might be seen across whole outcome measures; NS: Not significant result; **Intervention targets >1 mental disorder in its strategies | ||

Table 2: Direction of the association of the intervention related to the outcome.

Discussion

This systematic review identified nine relevant studies for universal school-based child mental health interventions. Interventions for children with mental health illnesses were excluded from this systematic review. Most of the studies originated from Europe, more developed countries and targeted an overlap of many mental health illnesses among children. Mental health illnesses were diagnosed in one of five children in Europe [3]. In Sichuan Province of China in 2014, a study across children aged 6-16-year-old showed that 19.13% of children who have any DSM-IV psychiatric disorder [26]. In Malaysia, NJMS2015 showed 12.1% prevalence based on the screening tool used [9]. The higher burden of mental health illness among the children in developed countries might explain why more studies were concentrated there, together with better support for large-scale or interventional research.

The studies used in the data extraction for present study have different modalities in the intervention ranging from individual meditation and counseling, to class and peer social and communication improvement. The duration of intervention ranged from six weeks to three years. Within this time range, a few outcomes in eight of nine of the studies showed some impact following the interventions. Duration wise, there was no clear cut evidence on how long an intervention should be, however, a section in a book on school trials mentioned two studies that conducted long-term follow-up found that significant differences between the intervention were sustained up to 12 years post intervention [27,28]. The underpinning theories behind a successful behavioral studies were related to intensity of the message which looked at the impact of national versus community interventions for example banning of smoking inside a building causing people to smoke outside [27]. People are forced to change to a new oath when the old path is banned and externalities message where the intervention stresses the harm that will happen to others, not just themselves will promote in behavioral change as peer effects [25]. Furthermore, peer influence can be improved if the interventions were delivered before the students enter the middle school [27].

GRADE scoring was used to assess the quality of the studies [29]. The scoring ranges from low to moderate. Some studies did not mention any withdrawals of subjects in their reports. All except one had a degree of non-randomization in the design which will introduce selection bias. Furthermore, some had as low as 42 participants and used non-equivalent comparison group design which could introduce serious selection bias. Most used quasi-experimental design which similarly, would introduce selection bias to the study.

The present systematic review provides some understanding in designing a more acceptable design of a universal school-based mental health intervention by looking at a few aspects that are (1) theory or model in designing the intervention such as Investigation, Vision, Action, Change (IVAC) model used in designing the Up intervention; (2) the targeted population i.e. whether targeting at individual schoolchildren and class level or targeting up to the community or policy level as in the socio-ecological model. Most of the studies used certified trainer which would lead to sustainability problem; (3) modality used such as story-telling or mindfulness strategy; bearing in mind the type of mental illness in focused; (4) outcomes measurement that is meaningful; and (5) duration of intervention and length of monitoring and evaluation (as part of follow-up).

The present review has some limitations. Most published studies used in present review have suboptimal study designs, which may lead to bias results. Our study was restricted to articles published in English language and local literatures only including the theses done in UKM. Reviewers had different levels of experience in conducting systematic review which could influence the interpretation and judgment on the inclusion and exclusion of studies during review. In future, more local databases especially those using Malay language could be included to find a more culturally-sensitive intervention.

Conclusions

Almost all school-based mental health interventions in present review were proven to have positive impact on mental health among school children, on the socio-emotional learning aspects inclusive of the social competency skill and cognitive control. Approaching primary school pupils to implement school-based mental health interventions have a good potential in reducing mental health problems by improving behavioral change since very young age. Comprehensive intervention conducted by familiar person such as teacher, together with parent participation has proved given impact on child mental health.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000) Children’s mental health.

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A (2003) Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60: 837-844.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ (2001) The Christchurch health and development study: Review of findings on child and adolescent mental health. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 35: 287-296.

- Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA (2015) Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56: 345-365.

- Malaysian Psychiatry Association (2008) Mental disorders in children and adolescents. A healthy mind in a healthy body.

- Brauner CB, Stephens CB (2006) Estimating the prevalence of early childhood serious emotional/behavioral disorders: Challenges and recommendations. Public Health 121: 303-310.

- Buka SL, Monuteaux M, Earls F (2002) The epidemiology of child and adolescent mental disorders. (2nd edn). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons Inc.

- Ahmad N, Yusoff FM, Ratnasingam S, Mohamed F, Nasir NH, et al. (2015) Trends and factors associated with mental health problems among children and adolescents in Malaysia. Int J Cult Ment Health 8: 125-136.

- Institute for Public Health (IPH) (2015) National health and morbidity survey 2015 (NHMS 2015). Vol. II: Non-communicable diseases, risk factors & other health problems.

- Low SK, Kok JK, Lee MN (2013) A holistic approach to school-based counselling and guidance services in Malaysia. School Psychol Int 34: 190-201.

- Franklin CGS, Kim JS, Ryan TN, Kelly MS, Montgomery KL (2012) Teacher involvement in school mental health interventions: A systematic review. Child Youth Serv Rev 34: 973-982.

- Whitley J, Smith JD, Vaillancourt T (2013) Promoting mental health literacy among educators. Canadian J School Psycholog 28: 56-70.

- Collins S, Woolfson LM, Durkin K (2014) Effects on coping skills and anxiety of a universal school-based mental health intervention delivered in Scottish primary schools. School Psychol Int 35: 85-100.

- Polanin JR, Espelage DL, Pigott TD (2012) A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychol Rev 41: 47-65

- Nielsen L, Meilstrup C, Kubstrup NM, Vibeke K, Bjørn Evald H (2015) Promotion of social and emotional competence: Experiences from a mental health intervention applying a whole school approach. Health Edu 115: 339-356.

- Adriaanse M, Van Domburgh L, Zwirs B, Doreleijers T, Veling W (2015) School-based screening for psychiatric disorders in Moroccan-Dutch youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 9: 13

- Van De Weijer-Bergsma E, Langenberg G, Brandsma R, Oort FJ, Bögel SM (2014) The effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness training as a program to prevent stress in elementary school children. Mindfulness 5: 238-248.

- Schonert-Reichl K A, Oberle E, Lawlor MS, Abbott D, Thomson K, et al. (2015) Enhancing cognitive and social emotional development through a simple to administer mindfulness based school program for elementary school children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dev Psychol 51: 52-66.

- Yoo YG, Lee DJ, Lee IS, Shin N, Park JY, et al. (2016) The effects of mind subtraction meditation on depression, social anxiety, aggression, and salivary cortisol levels of elementary school children in South Korea. J pediatr nurs 31: e185-e197.

- Opre A, Buzgar R, Dumulescu D (2013) Empirical support for self kit: A rational emotive education program. J Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies 13: 557-573.

- Cappella E, Hamre BK, Kim HY, Henry DB, Frazier SL, et al. (2012) Teacher consultation and coaching within mental health practice: cassroom and child effects in urban elementary schools. J Consult Clin Psychol 80: 597-610.

- Karasimopoulou S, Derri V, Zervoudaki E (2012) Children's perceptions about their health-related quality of life: Effects of a health education-social skills program. Health Educ Res 27: 780-793.

- Usera JJ ( 2017) The efficacy of an American Indian culturally-based risk prevention program for upper elementary school youth residing on the northern plains reservations. J Prim Prev 38: 175-194.

- Qu Y, Jiang H, Zhang N, Wang D, Guo L (2015) Prevalence of mental disorders in 6–16-Year-old students in sichuan province, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12: 5090-5107.

- Institute Of Medicine (US) Committee on health and behavior: Research policy (2001) Individuals and families: Models and interventions. health and behavior: The interplay of biological, behavioral, and societal influences. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

- Ryan R, Hill S (2016) How to GRADE the quality of the evidence. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group.

Citation: Sutan R, Nur Ezdiani M, Muhammad Aklil AR, Diyana MM, Raudah AR, et al. (2018) Systematic Review of School-Based Mental Health Intervention among Primary School Children. J Community Med Health Educ 8: 589. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000589

Copyright: © 2018 Sutan R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 7058

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Apr 03, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 6072

- PDF downloads: 986