Research Article Open Access

Surgery vs. Endoscopy Competitive or Complementary Tools for Management of Post Cholecystectomy Problems 10 Years' Experience in Major Referral Center

Alaa Ahmad Redwan*

Professor of Surgery & Laparoendoscopy, Assuit university hospitals, Assuit University, Egypt

- *Corresponding Author:

- Alaa Ahmed Redwan

Professor of surgery and Laparoendoscopy

Assuit university hospitals, Assuit University, Egypt

Tel: 0101988455

E-mail: ProfAlaaRedwan@Yahoo.com

Received date: December 24, 2013; Accepted date: January 27, 2014; Published date: February 06, 2014

Citation: Redwan AA (2014) Surgery vs. Endoscopy Competitive or Complementary Tools for Management of Post Cholecystectomy Problems 10 Years’ Experience in Major Referral Center. J Gastroint Dig Syst 4:167. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000167

Copyright: © 2014 Redwan AA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Gastrointestinal & Digestive System

Abstract

Purpose: A prospective work to study and evaluate surgical and endoscopic techniques used in management of post cholecystectomy problems. Patients and Methods: In the period from Mars 2000 to October 2009, a random sample of 630 patients (366 females and 264 males) were collected from general surgery department, and gastro-intestinal endoscopy unit, Assuit University hospitals, and managed accordingly using surgery in 143 patients, and endoscopy in 482 patients (plus percutaneous techniques in 25 patients). Results: Endoscopy was very successful as an initial treatment of 457 patients (73%), as being less invasive, low morbidity and mortality, competitive to surgery in treatment of missed stone (88%), mild to moderate biliary leakage (82%), and biliary stricture (74%). Its success increased by addition of percutaneous techniques in 4%, 2.8% & 8.3% for missed stone, leakage, and stricture respectively. But endoscopy was somewhat complementary to surgery in major leakage, and massive stricture, and surgery was resold to in 15%, and 17% of cases. Surgery remain as the treatment of choice in complex problems, and endoscopy play a complementary role in such cases of transection, ligation, combined problems of stones, stricture, and leakage (<40%), compared to 60% for surgery. Bilio-enteric anastomosis was the procedure of choice, done in 86 cases, with stent splintage in unhealthy, or small sized ducts. And stricture complication was encountered in 6% of cases treated by percutaneous rout in 4, and redo surgery in 1 case. The learning curve seems influential in both endoscopy and surgery. The cumulative experience increase the success rate of endoscopy from initial 50% to 95% nowadays, also surgery improved with decreased morbidity and mortality as complications encountered was seen in initial experience and decreased with time. Conclusion: Endoscopy was competitive to surgery in simple problems and advised to be the initial treatment choice, but complementary in major leak, ligation, transection, and complex problems, where surgery plays the main role in treatment with its invasiveness, high morbidity and morbidity. Cumulative experience influence endoscopic and surgical treatment of such problems and it is mandatory with other facility and equipment for management of such challenging cases.

Keywords

Post-cholecystectomy; ERCP; PTC; PTD; Bilio-enteric anastomosis

Introduction

Cholecystectomy has been the treatment of choice for symptomatic gallstones. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has recently become the more preferred operation over open cholecystectomy (OC). However, several studies report [1-4] that complications to the biliary tract are more common with LC (0.6% vs. 0.3%) [3], and leakage incidence of 1.1% [5]. Several authors [1,2] impute it to a ‘‘learning curve phenomenon’’, which frequently occurs after the introduction of any new procedure or technology, thus this is still a controversial data.

Post cholecystectomy problems are seen in as many as 20% of cases and manifested by symptoms of right hypochondrial pain, vomiting, or jaundice, otherwise biliary leakage and major biliary injuries [6].

Biliary injuries continue to be a significant problem following cholecystectomy [5], liver transplant [7], trauma [8], or infection [9]. Traditionally, surgery has been the gold standard for the management of biliary injuries. Recently, various endoscopic methods have been used as the preferred modalities of these patients [8,10], as it permitted a less invasive approach, with similar or reduced morbidity rates at surgical treatment [11,12], and since 1990s these endoscopic approaches nearly replaced surgical treatment [13].

Endoscopic intervention is a safe and effective method of treatment of post cholecystectomy biliary injuries as it can combine both the investigative and therapeutic arms in one common procedure [14]. However, management should be individualized based on factors such as outpatients or inpatients, presence of stone, stricture, ligature, or coagulopathy [15]. However, New endoscopic approaches allow less invasive treatment [16]; therefore, postponing or even avoiding surgical treatment [17], and should be the initial management of choice [18].

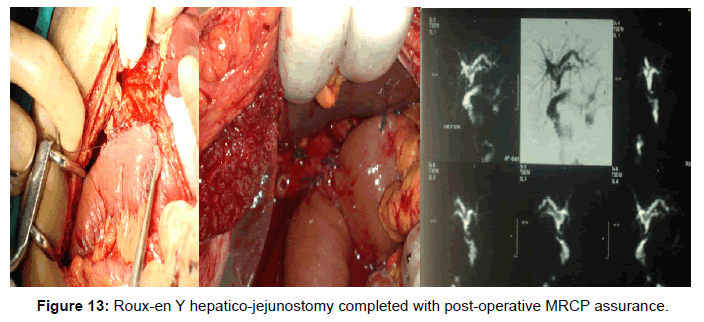

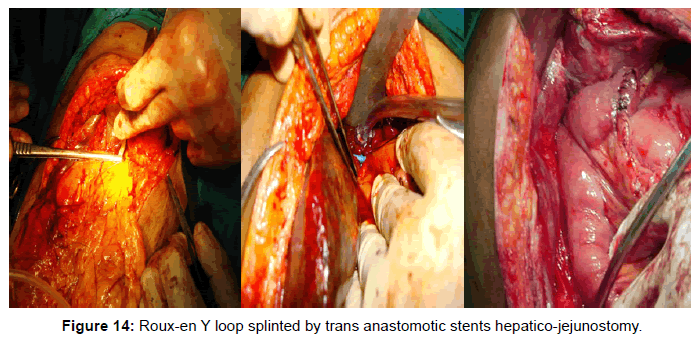

Surgical treatment still is the corner stone of treatment; it involves anastomosing an isolated loop of jejunum to the healthy, vascularized and unscarred part of the bile duct, as conventional surgical wisdom dictates avoiding the scarred and unhealthy part of the stricture for anastomosis. Roux-en-Y hepatico-jejunostomy is a one-time, proven effective and durable method of treating postoperative bile duct injuries, even for recurrent strictures, and has been shown to give good long-term results [19] (Figure 14), sometimes with the use of transanastomotic stents according to the individual characteristics of each patient and the experience of each surgeon. But its use is recommended when unhealthy (ischemic, or scarred) and small ducts (<4 mm) are found [20].

As compared to surgery, endoscopic treatment has the advantage of being less ‘invasive’ but it is less effective, sometime needs multiple sessions, and is certainly not suitable for all patients. In patients with strictures affecting the region of biliary bifurcation and in those with significant loss of length of bile duct, endoscopic stenting has a high chance of failure [21].

The aim of this work to emphasize, and evaluates the role of both endoscopy and surgery, whether it is competitive or complementary in management of each aspect of post cholecystectomy problems, respecting the experience curve for more than 10 years in this field in a major referral center in upper Egypt.

Patients and Methods

Random sample of patients were incorporated in this study for about 10 years period from the surgery department, and gastrointestinal endoscopy unit, Assuit University Hospitals (a major tertiary referral center in Upper Egypt). All patients complaining of post cholecystectomy problems (patients with non-biliary problems, or associated with vascular injuries are excluded), Patients was encountered with variable presentation, and timing from the surgical insult till referred to our center for management.

Cases were subjected to

• Thorough detailed history taking.

• Meticulous clinical examination.

• Investigation needed to diagnose the problem as: Liver function tests and abdominal ultrasonography were done to all cases.

• CT or MRI was done in some cases.

• Cholangiogram was done in all cases (the gold standard evaluation of biliary injuries [14]) as trans-tube cholangiogram (with aT tube in place), endoscopic cholangiogram (ERCP) in most of cases, or percutaneous trans-hepatic cholangiogram (PTC) in some selected cases in which endoscopic approaches failed.

Patients were categorized according to the problem diagnosed by the previous tools into 4 categories:

1) Missed stone(s) group.

2) Biliary leakage group.

3) Biliary stricture group.

4) Complex biliary problems group includes a combination of problems.

Each group was managed according to its circumstances by a stepwise manner of treatment starting with minimally invasive tools (endoscopic treatment, alone or in addition to percutaneous manipulation in difficult cases), to more invasive tools (surgical approaches).

Endoscopic approaches was done for most of our cases (510 patients) using side viewing Pentax video scope, using regular instruments, and blended current was used in sphincterotomy; however balloon sphincteroplasty was also used in some cases.

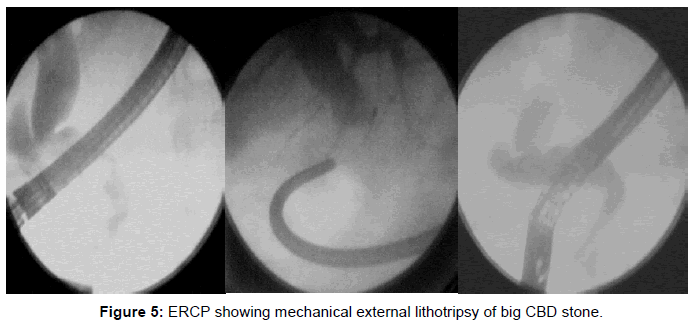

CBD stone(s) were treated by sphincterotomy and retrieval using basket, balloon extractor, or manual mechanical lithotripsy (Figure 5). However, Drainage was done in some cases with suspected cholangitis, or after failure of endoscopic techniques prior surgery by stents or nasal biliary catheter (Figure 2).

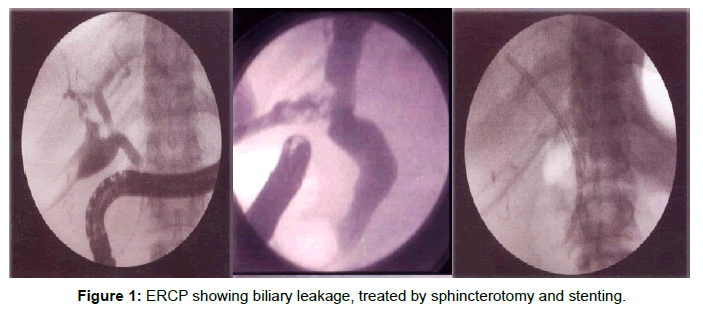

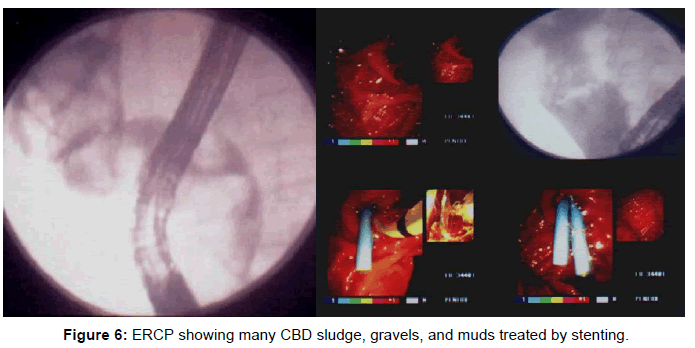

Biliary leakage was classified according to Strasburg, and Soper classification [3], and treated endoscopically by sphincterotomy in mild cases and/or stenting in moderate to major leakage, but endoscopic maneuvers failed in CBD transection injuries (Figure 6).

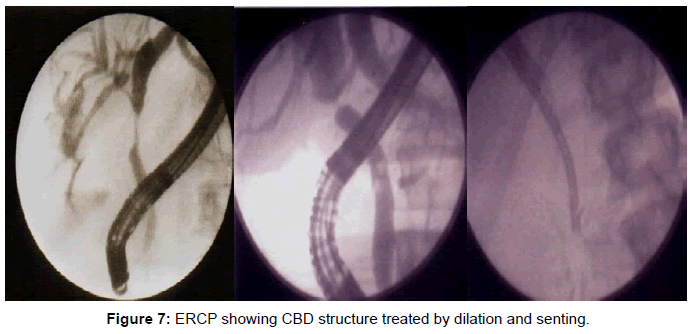

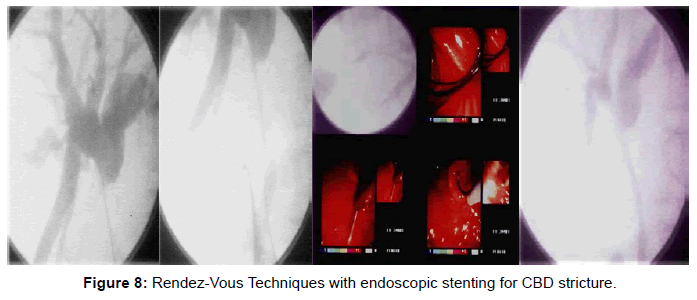

CBD stricture was categorized according to the Strasberg classification [3], and treated endoscopically by dilatation and stenting in repeated endoscopic sessions with upgrading of stents till reaching cure (after full dilatation of the stricture segment as evident by loss of the waist in cholangiogram, or after full dilation for 2 years from initial session) (Figure 8).

Complex biliary injuries were treated accordingly with special attention to the learning curve and cumulative experience for about 10 years in management of such problems.

Percutaneous Manipulation: was done in cases of endoscopic failure to opacity the proximal biliary tree as in major CBD injuries, or ligation through percutaneous trans hepatic cholangiogram (PTC) prior surgery, percutaneous manipulations and guide wire deployment through the CBD prior combined procedures (Rendezvous technique), or percutaneous dilatation, and stenting for stricture, or injury.

Surgical approaches: was done for a small number of patients (85 cases) for the following maneuvers:

• Peritoneal lavage and drainage for biliary peritonitis.

• Choledocho-lithotomy procedure to extract CBD stone(s), followed by T tube drain placement.

• CBD repair on a T tube splint in minor laceration injury of CBD.

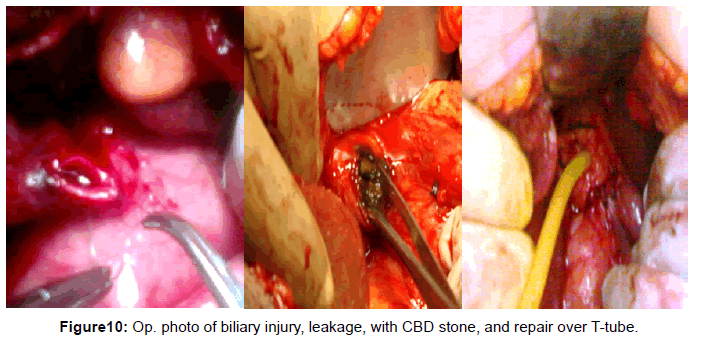

• Undo ligation with T-tube splint if CBD ligation was discovered very shortly after operation.(Figure 10)

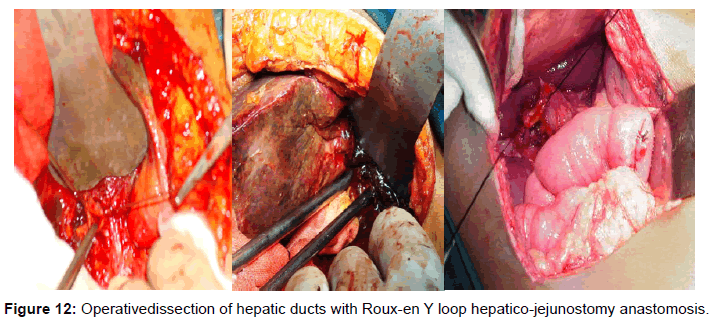

• Bilio-enteric shunt operation (with the use of Roux-en Y loop technique and choledocho-jejunostomy as the operation of choice), for CBD injury, massive stricture fibrosis, or bad patient compliance with repeated endoscopic session and stenting. The anastomotic line was splinted by stents in small, unhealthy ducts.

Follow up: Parenteral antibiotics were prescribed for all cases (Ciprofloxacin).

Surgically treated cases were followed up for a variable period prior discharge (3-10 Days) with the appropriate treatment and follow up.

Endoscopically and percutaneously treated cases were discharged at the same day after assurance of the stable condition of the patient.

Data of all patients were collected, and categorized, with thorough discussion of the detailed results of treatment was done for each category to reach a consensus either endoscopic maneuvers can substitute surgery as a definitive treatment of such problem (a competitive treatment), or surgery still is needed for definitive treatment and these maneuvers are just a complementary tools prior surgery.

Results

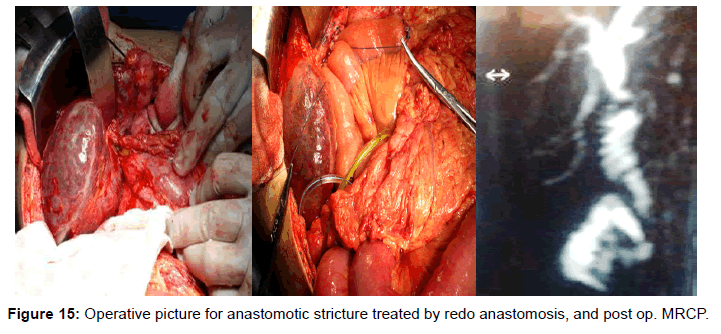

From Mars 2000 to October 2009, 630 cases of post cholecystectomy problems were incorporated in this study, the mean age was 45.3 years with a range of 18-68 years, 350/630 were females, and only 50 cases (8%) of them were operated in our center. Cases included either presented early (within a month post operatively) (Figure 15) in 288 cases, or late in 342 cases as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

| Durationā?ŗ & itemā?¼ |

1-5 days | 6-10 days | 11-15 days | 16-20 days | 21-25 days | 21-25 days | Total ā?¼ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| Leakage | 33 | 5.2 | 57 | 9 | 15 | 2.4 | - | - | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0.5 | 114 | 18.1 |

| Cholangio- Abnormality | - | - | 15 | 2.4 | 51 | 8.1 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 0.5 | 69 | 11 |

| Jaundice | 30 | 4.8 | 15 | 2.4 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0.5 | 9 | 1.4 | 6 | 1 | 69 | 11 |

| Leakage, and jaundice | - | - | 3 | 0.5 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | - | - | 21 | 3.3 |

| Colic, and infection | - | - | - | - | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0.5 | - | - | 6 | 1 | 15 | 2.4 |

| Total | 63 | 10 | 90 | 14.3 | 84 | 13.3 | 12 | 2 | 21 | 14.7 | 18 | 2.9 | 288 | 45.8 |

Table 1: Early presentations and their incidence.

| Durationā?ŗ Itemā?¼ |

6 months | 1year | 2years | 5yrears | 10years | ↑10years | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| Jaundice | 60 | 9.5 | 24 | 3.9 | 42 | 6.7 | 39 | 6.2 | 24 | 3.9 | 45 | 7.1 | 234 | 37.1 |

| Colic | 24 | 3.9 | 12 | 2 | 24 | 3.9 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 1.4 | 81 | 12.9 |

| Cholangitis | - | - | 3 | 0.5 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.5 | 21 | 3.3 |

| Fistula | 6 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | 1 |

| Total | 90 | 11.4 | 39 | 6.2 | 72 | 11.4 | 51 | 8.1 | 33 | 4.8 | 57 | 9 | 342 | 54.3 |

Table 2: Late presentations and their incidence.

Most of our cases (490 cases about 78%) presented after open access approaches (cholecystectomy alone in 370 cases, and with CBD exploration in120 cases), versus 140 cases presented after laparoscopic approaches (22%).

Investigations

Cholangiogram was the main step of diagnosis in these cases, and was done for nearly all patients (582/630 about 92% of cases), by endoscopy in 510 patients (81%), complemented by percutaneous trans hepatic rout in 41 patients (6.5%), and MRCP in 95 patients (15%), as shown in Table 3.

| Cholangiogram findings | No | % |

|---|---|---|

| *Dilatation of biliary channels | 310 | 49.2 |

| *Stone: •Single stone •Multiple stones (2-13) |

168 45 |

27 7.1 |

| *Leakage: •Minor leakage •Major leakage |

80 46 |

12.7 7.3 |

| *Stricture: •Mid CBD •High CBD •Low CBD |

68 25 28 |

10.8 4 4.4 |

| *Complex problems: •Arrest of the dye (?? ligated CBD) •Transection of CBD •Stone, and leakage •Stricture, and leakage •Stone and stricture •Post-operative anastomotic stricture |

29 18 20 17 14 5 |

4.6 2.9 3.2 3 2.2 0.8 |

| * No detected abnormality. | 19 | 3 |

| Total | 582 | 92.4 |

| Cholangiogram findings | No | % |

| *Dilatation of biliary channels | 310 | 49.2 |

| *Stone: •Single stone •Multiple stones (2-13) |

168 45 |

27 7.1 |

| *Leakage: •Minor leakage •Major leakage |

80 46 |

12.7 7.3 |

| *Stricture: •Mid CBD •High CBD •Low CBD |

68 25 28 |

10.8 4 4.4 |

| *Complex problems: •Arrest of the dye (?? ligated CBD) •Transection of CBD •Stone, and leakage •Stricture, and leakage •Stone and stricture •Post-operative anastomotic stricture |

29 18 20 17 14 5 |

4.6 2.9 3.2 3 2.2 0.8 |

| * No detected abnormality. | 19 | 3 |

| Total | 582 | 92.4 |

Table 3: Cholangiographic finding.

Patients’ categorization

Cases were categorized into the following four groups and managed accordingly

Missed stone(s) group {213 cases}

All of those patients were diagnosed preliminary by abdominal sonography, CT scan, MRCP, and endoscopic cholangiogram, and managed as shown in Table 4.

| treatment of stone | No | % |

|---|---|---|

| Endoscopic stone retrieval: •Stone retrieval by basket •Stone retrieval by balloon •Combined basket & balloon •Mechanical internal lithotripsy •Mechanical external lithotripsy |

83 31 38 9 20 |

13.2 5 6 1.4 3.2 |

| Bad general condition & stenting with re-do ERCP after a weak | 7 | 1.1 |

| Rendez-Vous technique and endoscopic stone extraction. | 9 | 1.4 |

| Failed endoscopic retrieval and stenting prior surgery | 16 | 2.5 |

| Surgical treatment by Choledocho-lithotomy with T tube drainage of CBD | 16 | 2.5 |

Table 4: Stone treatment techniques.

Biliary leakage group {145 cases}

Cholangiogram demonstrated leakage as minor degree in 80 cases (55%), major leakage in 46 cases (32%). but in 19 patients leakage evident clinically failed to be demonstrated by cholangiogram (13%), probably from minor ductules or from gall bladder bed as shown in Table 5.

| Leakage treatment | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sphincterotomy for clinical leakage with free cholangiogram (19) | 19 | 3 |

| Sphincterotomy and stenting for mild leakage(typeA), (80) | 75 | 12 |

| Sphincterotomy and stenting for marked leakage (B,C,D,E), (46) | 27 | 4.3 |

| Rendez-vous techniques and endoscopic stenting (46) | 4 | 0.6 |

| Surgery for failed cases (20), and bad compliance to endoscopy (2): • CBD repair over T tube • Bilio-enteric anastomosis |

7 15 |

1.1 2.4 |

Table 5: Biliary leakage treatment techniques.

Biliary structure group {121 cases}

Management of strictures by either endoscopy or surgery was shown in Table 6.

| Stricture treatment | No | % |

|---|---|---|

| Endoscopic sphincterotomy and dilatation of ampullary stricture | 15 | 2.4 |

| Endoscopic dilatation, stenting (80/121): • 8 fr. Stent. • 10fr. Stent. • 11.5 fr. Stent. • 12 fr. Stent. • Double stents |

5 32 18 14 11 |

0.7 5.1 2.9 2.2 1.7 |

| Rendez-vous technique &endoscopic stenting | 10 | 1.6 |

| Failed endoscopy, for surgery | 16 | 2.5 |

| Bad patient compliance, for surgery | 5 | 0.7 |

| Bilio-enteric shunt (Choledocho-jujenostomy) | 21 | 3.3 |

Table 6: Stricture treatment techniques.

Complex biliary problems {151 cases}

This group includes the following subgroups:

A. Leakage with biliary peritonitis (48/151)

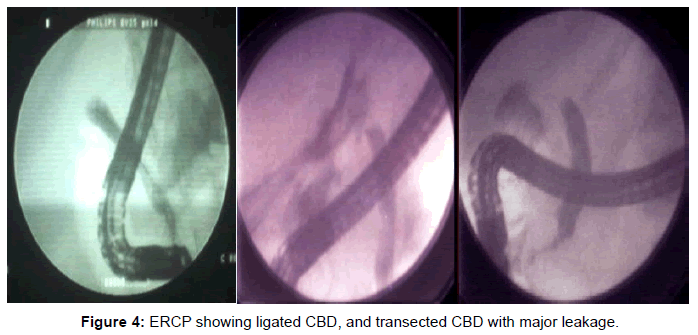

B. CBD ligation (29/151)

C. CBD transection injury (18/151)

D. CBD stone, with leakage (20/151)

E. CBD stricture, with leakage (17/151)

F. CBD stone, with stricture (14/151)

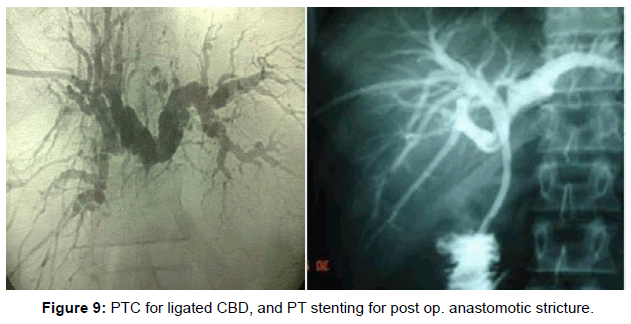

G. Post-operative anastomotic stricture after Roux-en-Y choledocho-jejunostomy (5/151) (Figure 9)

Endoscopic treatment in complex problems

Table 7 showed endoscopic treatment of complex biliary problems.

| Endotreatment in complex problems | N0. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Stenting for leakage after surgical drainage (30/151) | 25 | 4 |

| Stenting for CBD transection (18/151) | 2 | 0.3 |

| Stone retrieval and stenting for leakage with stones (20/151) | 15 | 2.4 |

| Dilation and stenting for stricture with leakage (17/151) | 12 | 2 |

| Stone retrieval and stenting for stone with stricture (14/151) | 6 | 0.9 |

| Rendez-vous technique plus endoscopic stone retrieval and stenting for stone with stricture (14/151) | 2 | 0.3 |

| Failed endoscopic techniques in complex problems (151) | 66 | 10.5 |

Table 7: Endoscopic treatment of complex biliary problems.

Percutaneous manipulations in complex problems

This approach was done in 12 patients in conjunction with endoscopy in 2, and alone in 10 cases, it was therapeutic in 5, and prior surgery in the other 5 patients.

Table 8 showed percutaneous treatment of complex biliary problems.

| PTC in complex problems | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| P.T.C. and stenting for stricture and leakage (17/151) | 1 | 0.2 |

| Rendez-vous techniques plus endoscopy for stone with stricture (14/151) | 2 | 0.3 |

| P.T.D. for ligated CBD in bad patient condition prior surgery (29/151) | 5 | 0.8 |

| P.T.C. and percutaneous dilation and stenting for post-operative anastomotic stricture (5/151) | 4 | 0.6 |

| Total attempts by percutaneous rout | 12 | 2 |

Table 8: Percutaneous treatment of complex biliary problems.

Surgical treatment for complex problems

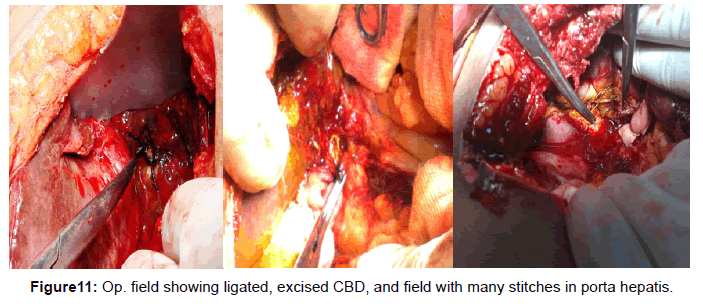

This approach was done in 109/151 cases (72.2%), with 114 attempts, and it was urgently done in 48 patients with biliary peritonitis, or electively in the rest. In 30 cases, it was done as peritoneal drainage only prior further tools for treatment; however it was a definitive treatment in 89 cases, preceded by MRCP in 61 cases, or P.T.C. in 5 cases.

Table 9 showed surgical treatment of complex biliary problems.

| Surgery of complex problems | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Leakage with biliary peritonitis (48/151): • Just drainage, and peritoneal toileting • Drainage, choledocholithotomy plus T.tube • Drainage, CBD repair over T tube splint • Drainage, CBD undo ligation, T tube splint • Bilio-enteric anastomosis for failed endoscopic treatment (30/48) |

30 3 8 7 5 |

4.8 0.5 1.3 1.1 0.8 |

| Bilio-enteric anastomosis for ligated CBD (29/151) | 29 | 4.6 |

| Bilio-enteric anastomosis for transected CBD (18/151) | 16 | 2.5 |

| Choledocholithotomy, and CBD repair over T tube for stone with leakage (20/151) | 5 | 0.8 |

| Bilio-enteric anastomosis for stricture with leakage (17/151) | 4 | 0.6 |

| Choledocholithotomy, stricturoplasty, and T tube splint for stone with stricture (14/151) | 5 | 0.8 |

| Bilio-enteric anastomosis for stone with stricture (14/151) | 1 | 0.2 |

| Re-do anastomosis of roux loop Choledocho-jejunostomy for post op. stricture (5cases out of 86 bilio-enteric anastomosis in this work) |

1 | 0.2 |

| Total surgical attempts in treatment of complex biliary problems (151) | 114 | 18.1 |

Table 9: Surgical treatment of complex biliary problems.

Table 10 showed the definitive treatment of post cholecystectomy problems.

| Endoscopic treatment | Endoscopy + percutaneous treatment | Percutaneous treatment | Surgical treatment | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Missed stone(s) | 188 | 88% | 9 | 4% | - | - | 16 | 7.5% | 213 | 34% |

| Biliary leakage | 119 | 82% | 4 | 2.8% | - | - | 22 | 15% | 145 | 23% |

| Biliary stricture | 90 | 74% | 10 | 8.3% | - | - | 21 | 17% | 121 | 19% |

| Complex biliary problems | 60 | 40% | 2 | 1.3% | 5 | 3.3% | 84 | 56% | 151 | 24% |

| Total | 457 | 73% | 25 | 4% | 5 | 0.8% | 143 | 23% | 630 | 100% |

Table 10: The definitive treatment of post cholecystectomy problems.

The learning experience curve of ERCP

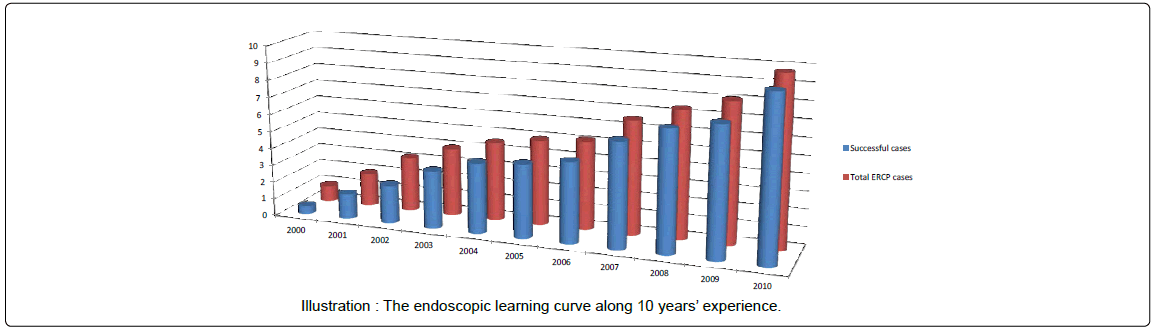

The learning curve of the cumulative experience appeared to be crescendo in manner progressively in direct proportion to increasing number of referral cases to the center (10-20 cases for ERCP /monthly in 2000 to 20-30 cases for ERCP/weekly in 2010) with increasing number of successful cases (with an incidence of 50% at initial attempts of ERCP at 2000, reaching about 90-95% in 2010)

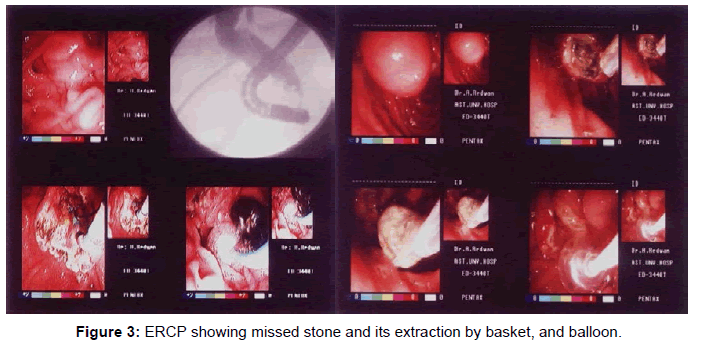

Two humps in the experience curve was encountered at 2003 by the introduction of percutaneous manipulation techniques that helps to avoid failure of ERCP cases (e.g. difficult cannulation, dilation of tough tight stricture segment, delineation of proximal biliary tree, and stenting for stricture not reached by ERCP). The other hump was encountered at 2005 by introduction of various innovations of manual mechanical lithotripsy, new balloon dilators, and revolutions of steno therapy (Figure 3).

The learning experience of surgical treatment

The learning curve of experience of surgical treatment also passed in a similar fashion with a cumulative manner for 10 years with treatment of such problems, with more than 86 operations of bilioenteric shunt procedures in these challenging cases of relatively nondilated biliary channels, with sepsis and fibrous scarring of the field. Variable techniques was practiced including end to side, versus side to side procedures, splinted versus non splinted anastomotic stoma, inside stent versus trans hepatic percutaneous catheter splint, interrupted versus continuous sutures anastomosis, depending on patient circumstances, but generally anastomosis is done as Roux-en-Y loop Choledocho-jujenostomy end to side, single interrupted layer of 3/0, or 4/0 Vicryl sutures, tension free, mucosa to mucosa, 2-3 cm stoma, splinted in very small ducts by biliary stent.

These cumulative experience was revealed as decreasing number of morbidity following these major surgeries, and also the resulting complications especially stricture at the anastomotic line. 5 out of 86 cases suffers from stricture of the stoma (5.8%), most of them belongs to early cases in initial experience, and due to cumulative experience in treatment of such cases percutaneous treatment was adopted and only 1/5 cases needed redo-surgery for refashioning of the anastomosis (Figure 12).

Discussion

The incidence of post cholecystectomy problems in this work was higher after conventional open cholecystectomy (490 cases) more than laparoscopic cholecystectomy (140 cases). In contrary to the generallyaccepted higher incidence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (0.6%) more than open cholecystectomy (0.3%), and this may be attributed to the low incidence and affinity for laparoscopic procedures in Upper Egypt locality.

Choledocholithiasis (213 patients): were successfully treated endoscopically in 88% of cases to extract the stone(s) that increased to 92% with the addition of rendez-vous techniques (197/213) (Figure 8). The failure rate of endoscopic treatment detected was 12% (25/213), but it was reduced by addition of rendezvous technique to become 7.5% (16/213), in contrary to other authors incidence that increased up to 20% failure rate [22] and this may be explained by the fact that most of the stones encountered in this work was soft, or easily crushed improving the success rate. For those cases with endoscopic failure, drainage by biliarystenting was done prior surgery [23]. Moreover endoscopic CBD clearance rate of stone(s) in those patients reached 100% as evident by post ERCP follow up diagnostic tools (Figure 7).

Only 7.5% of cases (16/213) underwent surgical treatment by choledocholithotomy procedure, preceded by MRCP in 5 cases, and other pre requisites and preoperative assessment as surgery is invasive tool, with long hospital admission period, higher coast, and high morbidity and mortality rates, So, endoscopic treatment substituted surgery in all those 197 cases (92%) as a competitive definitive treatment for missed stones [14,17], moreover it has the superiority as regard less invasivenesss [8,11,16], less coasty, without hospital admission (outpatient techniques), with a very low if absent morbidity and mortality rates [12,13].

Bile leakage was common among our patients (145 cases= 23%) seen as bileleakage in 139 patients, or bile fistula in 6 patients [5], usually leakage originated from the liver bed or biliary injury [24], as the sphincter of Oddi creates a pressure gradient that result in bile spillage to outsiderather than into the duodenum [25]. Leakage was demonstrated by cholangiogram in most of cases (126/ 145), however the spillage was very mild and not evident by contrast injection in 19 cases, such mild cases of biliary leak may resolve spontaneously (Figure 4) [5].

Endoscopic treatment was based on the degree of leakage. Patients with mild degree leakage (Cystic duct stump leak, IHBD, lateral section of CBD/RHD, gall bladder bed) was treated efficiently by endoscopic sphincterotomy and stenting for at least a month [11,26-29], subsequently leakage ceased within 3-5 days in almost all cases(19/19, and 75/80) with success rate of 100%, 94% respectively, as endoscopic treatment accelerates the healing period by decompressing the biliary system in addition, close the defect physically and act as a bridge at the site of extravasation for major leakages. Stenting also acts as a mold and prevents stricture formation during the recovery period, and should be the preferred treatment [29].

In major leakage (type B, C, D, and E Strasberg & Soper classification), endoscopic treatment with sphincterotomy and stenting was successful in only 67% of cases (31/46) [26,30-32], moreover another session of ERCP and stenting were needed to dilate a resulting stricture and upgrade stenting at a later date in 12 out of 31 patients treated, this results is comparable with literature results [29].

Surgery was done in 22 cases (15.2%), 5 mild, 15 severe cases, and 2 patients with bad compliance to endoscopy, by CBD repair over a T- tube splint in 7 cases, and bilio enteric anastomosis in 15 cases splinted with biliary stent in 5 cases and trans-hepatic pigtail catheter in 2 cases. So, endoscopic treatment substituted surgery in all mild leakage cases as a competitive definitive treatment (19/19& 75/80), with 100%, and 94% success rates respectively. Unfortunately endoscopic approaches failed to substitutes surgery as a definitive treatment in cases of major leakage (31/46 cases) with only 67% success rate, and play a major complementary role with other additional tools. Thus surgery was resold to as the treatment of choice in spite of being used in only 15.2% of cases; without doubt it has its associated morbidity and mortality, prerequisites, and necessary facilities.

Biliary stricture {121 cases}: Endoscopic treatment was successfulin 105 patients (87%) with dilation and stenting, withmultiple sessions ERCP to substitute or upgrade stent then after, in agreement with literatures that ERCP and stenting has comparable efficacy with surgery with lower rates of morbidity and mortality [30-32], so endoscopy is the preferable initial therapy [33,34], but it needs a long period (About 24 months), and repeated endoscopic sessions [26], moreover Davis et al., reported equal relapses of 17% for both treatment [35]. Surgery was resold to in 21 cases (17.4 %), by Choledocho-jejunostomy preceded by P.T.C. in 6 cases, MRCP in 10 cases, or endoscopic treatment in 5 cases with bad compliance.

So Endoscopic treatment can substitute’s surgery as competitive treatment in initial stricture management in most of cases (87%), however it should be performed with progressive increment in the number of stents to better calibrates the stricture, stents should be replaced every 3 months before possible clogging could cause cholangitis, and inform the patient about the risk of stenting and the duration of treatment [36-38]. Otherwise surgery is indicated as the treatment of choice especially in surgically suitable patient [26].

Complex biliary problems {151 cases} the definitive treatment of such problems was mainly by surgical interference (56%), however endoscopy was a mandatory complementary tool in initial management either alone (40%), or with addition of percutaneous techniques (4.5%). So management of such problematic cases must be individualized [15], when the need for surgery becomes essential due to the nature of injury or to non response to other forms of treatment, it should be undertaken in a specialized unit with expert surgeons as the results is affected greatly by the learning curve [14], and this was evident in this work by improvement of the results with time and experience accumulation in both endoscopy and surgery.

Endoscopy is the preferable initial treatment [18,33,34] that effectively managed most bile duct injuries [39], however its use is limited to incomplete biliary strictures [26], biliary leakage [29,30,32] (Figure 1), and for surgically unsuitable patients [26], and if successfully done, its results are similar to surgical results [38], with less mortality [16]. But surgery remain the gold standard treatment especially in leakage with biliary peritonitis, ligated bile duct, complete biliary stricture, bile duct transection, or stricture after bilio-enteric anastomosis [15,40] (Figure 11), as patients with total obstruction are not amenable to endoscopic approaches [16].

Good long-term surgical results are obtained with Roux-en-Y hepatico-jejunostomy [20,41-44] (Figure 13). In this work, it was done with mucosa to mucosa, tension free, 2 cm stoma, single layer tecniques using Vicryl 2/0 or 3/0. Transanastomotic stents are selectively used with unhealthy (ischemic, or scarred), and small ducts (<4 mm) [20,45], to guard against post-operative stricture complications that was encountered in 5/86 cases (5.8%) in our patients, as documented in literatures that stenosis can occurs in 10-30% of cases [20,35,41,45-48].

Post-operative anastomotic stricture was treated by percutaneous dilation and stenting in 4/5 cases as it is very beneficial in such cases [49,50], and redo surgery was resold to in only one patient.

References

- Khan MH, Howard TJ, Fogel EL, Sherman S, McHenry L, et al. (2007) Frequency of biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy detected by ERCP: experience at a large tertiary referral center. Gastrointest Endosc 65: 247-252.

- Sakai P, Ishioka S, and MalufFilho F (2005) Tratado de endoscopiadigestivadiagnóstica e terapêutica. Viasbiliares e pâncreas. In: Matuguma SE, Melo J M, Artifon ELA e Sakai P. Estenoses e fístulasbiliaresbenignaspós-cirúrgicas e póstraumáticas. 10 ed. São Paulo: Atheneu 139-146.

- Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ (1995) An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 180: 101-125.

- Mirza DF, Narsimhan KL, Ferraz Neto BH, Mayer AD, McMaster P, et al. (1997) Bile duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: referral pattern and management. Br J Surg 84: 786-790.

- Mehta SN, Pavone E, Barkun JS, Cortas GA, Barkun AN (1997) A review of the management of post-cholecystectomy biliary leaks during the laparoscopic era. Am J Gastroenterol 92: 1262-1267.

- Ahrendt SA and Pitt HA (2001) Biliary tract. In: CM Townsend Textbook of Surgery. WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia, Pensylvania 1076-1111.

- Thuluvath PJ, Atassi T, Lee J (2003) An endoscopic approach to biliary complications following orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Int 23: 156-162.

- Singh V, Narasimhan KL, Verma GR, Singh G (2007) Endoscopic management of traumatic hepatobiliary injuries. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22: 1205-1209.

- Singh V, Reddy DC, Verma GR, Singh G (2006) Endoscopic management of intrabiliary-ruptured hepatic hydatid cyst. Liver Int 26: 621-624.

- Kaffes AJ, Hourigan L, De Luca N, Byth K, Williams SJ, et al. (2005) Impact of endoscopic intervention in 100 patients with suspected postcholecystectomy bile leak. Gastrointest Endosc 61: 269-275.

- Ferrari AP, Paulo GA, and Thuler FP. Endoscopia Gastrointestinal Terapêutica. In: SOBED. Terapêuticaendoscópicanascomplicaçõescirúrgicas e pós-transplanteshepáticos. 1o ed. São Paulo: Tecmedd 1463 -1476.

- Wills VL, Jorgensen JO, Hunt DR (2000) Role of relaparoscopy in the management of minor bile leakage after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 87: 176-180.

- ZOLTáN VÖLGYI, TÜNDE FISCHER, MáRIA SZENES, and BEáTA GASZTONYI (2010). Endoscopic Management of Post-Operative Biliary Tract Injuries. CEMED4: 153–162.

- Al Karawi MA, Sanai FM, Mohamed Ael S, Mohamed SA (2000) Endoscopic management of postcholecystectomy bile duct injuries: review. Saudi J Gastroenterol 6: 67-78.

- Singh V, Singh G, Verma GR, Gupta R (2010) Endoscopic management of postcholecystectomy biliary leakage. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 9: 409-413.

- De Palma GD, Persico G, Sottile R, Puzziello A, Iuliano G, et al. (2003) Surgery or endoscopy for treatment of postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures? Am J Surg 185: 532-535.

- Paula Peruzzi Elia, Jose Mauro Teixeira, Gutemberg Correia Da Silva, Gregrio Feldman, Fernando Peres, et al. (2008). Endoscopic Treatment of Biliary Fistula Post-Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy - Case Report. Braz. J. Video-Sur 1: 133-135.

- Bergman JJ, Burgemeister L, Bruno MJ, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ, et al. (2001) Long-term follow-up after biliary stent placement for postoperative bile duct stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc 54: 154-161.

- Chaudhary A, Chandra A, Negi SS, Sachdev A (2002) Reoperative surgery for postcholecystectomy bile duct injuries. Dig Surg 19: 22-27.

- Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Cano-Gutiérrez G, Chaparro JM, et al. (2002) To stent or not to stent bilioenteric anastomosis after iatrogenic injury: a dilemma not answered? Arch Surg 137: 60-63.

- Chaudhary A (2006) Treatment of post-cholecystectomy bile duct strictures--push or sidestep? Indian J Gastroenterol 25: 199-201.

- Cuschieri A, Croce E, Faggioni A, Jakimowicz J, Lacy A, et al. (1996) EAES ductal stone study. Preliminary findings of multi-center prospective randomized trial comparing two-stage vs single-stage management. Surg Endosc 10: 1130-1135.

- Maxton DG, Tweedle DEF, and Martin DF (1996) Retained common bile duct stones after endoscopic sphincterotomy : Temporary and long term treatment with biliary stenting. Gastrointest.Endosc 44: 105 - 106.

- McMahon AJ, Fullarton G, Baxter JN, O'Dwyer PJ (1995) Bile duct injury and bile leakage in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 82: 307-313.

- Barkun AN, Rezieg M, Mehta SN, Pavone E, Landry S, et al. (1997) Postcholecystectomy biliary leaks in the laparoscopic era: risk factors, presentation, and management. McGill Gallstone Treatment Group. Gastrointest Endosc 45: 277-282.

- Abdel-Raouf A, Hamdy E, El-Hanafy E, El-Ebidy G (2010) Endoscopic management of postoperative bile duct injuries: a single center experience. Saudi J Gastroenterol 16: 19-24.

- Agarwal N, Sharma BC, Garg S, Kumar R, Sarin SK (2006) Endoscopic management of postoperative bile leaks. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 5: 273-277.

- Do IN, Kim JC, Park SH, Lee JY, Jung SW, et al. (2005) [The outcome of endoscopic treatment in bile duct injury after cholecystectomy]. Korean J Gastroenterol 46: 463-470.

- Parlak E, Ciã§ek B, DiÅŸibeyaz S, Kuran SO, OÄŸuz D, et al. (2005) Treatment of biliary leakages after cholecystectomy and importance of stricture development in the main bile duct injury. Turk J Gastroenterol 16: 21-28.

- Sarmiento JM, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, Hodge DO, Harrington JR (2004) Quality-of-life assessment of surgical reconstruction after laparoscopic cholecystectomy-induced bile duct injuries: what happens at 5 years and beyond? Arch Surg 139: 483-488.

- Walsh RM, Vogt DP, Ponsky JL, Brown N, Mascha E, et al. (2004) : Management of failed biliary repairs for major bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Journal American College Surgery 199 : 192 – 197.

- Csendes A, Navarrete C, Burdiles P, Yarmuch J (2001) Treatment of common bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: endoscopic and surgical management. World J Surg 25: 1346-1351.

- al-Karawi MA, Sanai FM (2002) Endoscopic management of bile duct injuries in 107 patients: experience of a Saudi referral center. Hepatogastroenterology 49: 1201-1207.

- Draganov P, Hoffman B, Marsh W, Cotton P, Cunningham J (2002) Long-term outcome in patients with benign biliary strictures treated endoscopically with multiple stents. Gastrointest Endosc 55: 680-686.

- Davids PH, Tanka AK, Rauws EA, van Gulik TM, van Leeuwen DJ, et al. (1993) Benign biliary strictures. Surgery or endoscopy? Ann Surg 217: 237-243.

- Costamagna G, Pandolfi M, Mutignani M, Spada C, Perri V (2001) Long-term results of endoscopic management of postoperative bile duct strictures with increasing numbers of stents. Gastrointest Endosc 54: 162-168.

- Bergman JJ, Burgemeister L, Bruno MJ, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ, et al. (2001) Long-term follow-up after biliary stent placement for postoperative bile duct stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc 54: 154-161.

- Vitale GC, Tran TC, Davis BR, Vitale M, Vitale D, et al. (2008) Endoscopic management of postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures. J Am Coll Surg 206: 918-923.

- Pawa S, Al-Kawas FH (2009) ERCP in the management of biliary complications after cholecystectomy. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 11: 160-166.

- Palacio-Vélez F, Castro-Mendoza A, Oliver-Guerra AR (2002) [Results of 21 years of surgery in iatrogenic lesions of the bile ducts]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 67: 76-81.

- Tocchi A, Mazzoni G, Liotta G, Costa G, Lepre L, et al. (2000) Management of benign biliary strictures: biliary enteric anastomosis vs endoscopic stenting. Arch Surg 135: 153-157.

- Sicklick JK, Camp MS, Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Yeo CJ, et al. (2005) Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann Surg 241: 786-792.

- Walsh RM, Henderson JM, Vogt DP, Brown N (2007) Long-term outcome of biliary reconstruction for bile duct injuries from laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surgery 142: 450-456.

- Khalid MohamadAbouEl-Ella, Osama Nafea Mohamed, Mohamed Ibrahim El-Sebayel, Saleh Ali Al-Semayer, and Ibrahim Abdul Karim AlMofleh (2004) Management of Postlaparoscopic cholecystectomy major bile duct injury: Comparison of MRCP with conventional methods. The Saudi J. of Gastroenterology 10: 8-15.

- Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Campbell KA, et al. (2000) Postoperative bile duct strictures: management and outcome in the 1990s. Ann Surg 232: 430-441.

- Li Jie, Zhou Kejun, and Wu Dun (2005) Mucosa improved biliary-enteric anastomosis end to side in a small-caliber choledochojejunostomy application. J. Jiangsu University (Medicine Edition 15: 4124.

- House MG, Cameron JL, Schulick RD, Campbell KA, Sauter PK, et al. (2006) Incidence and outcome of biliary strictures after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 243: 571-576.

- Abdel Wahab M, el-Ebiedy G, Sultan A, el-Ghawalby N, Fathy O, et al. (1996) Postcholecystectomy bile duct injuries: experience with 49 cases managed by different therapeutic modalities. Hepatogastroenterology 43: 1141-1147.

- Antonio Ramos-De La Medina, Sanjay Misra, Andrew J Leroy, and Michael G. Sarr (2008) Management of benign biliary strictures by percutaneous interventional radiologic techniques (PIRT). HPB (Oxford) 10: 428-432.

- Hans-Ulrich Laasch (2010) Obstructive jaundice after bilioenteric anastomosis: Transhepatic and direct percutaneous enteral stent insertion for afferent loop occlusion. Gut Liver 4: 589- 595.

Relevant Topics

- Constipation

- Digestive Enzymes

- Endoscopy

- Epigastric Pain

- Gall Bladder

- Gastric Cancer

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastrointestinal Hormones

- Gastrointestinal Infections

- Gastrointestinal Inflammation

- Gastrointestinal Pathology

- Gastrointestinal Pharmacology

- Gastrointestinal Radiology

- Gastrointestinal Surgery

- Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

- GIST Sarcoma

- Intestinal Blockage

- Pancreas

- Salivary Glands

- Stomach Bloating

- Stomach Cramps

- Stomach Disorders

- Stomach Ulcer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15014

- [From(publication date):

February-2014 - Apr 26, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10445

- PDF downloads : 4569