Research Article Open Access

Suicide and Marriage Rates: A Multivariate Analysis of National Data from 1970-2013 in Jamaica

Paul Andrew Bourne1*, Angela Hudson-Davis2, Charlene Sharpe-Pryce3, Ikhalfani Solan4, Shirley Nelson51Socio-Medical Research Institute, Jamaica

3Northern Caribbean University, Mandeville, Jamaica

4South Carolina State University, USA

5Barnet Private Resort, Bahamas

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

Introduction: Suicide is an indication of psychiatric disorder, which is more associated with marital discord than marital unions. Despite the widely held view that suicide is not usually associated with maritial union, there is empirical evidence linking suicides to marriages.

Objective: This study seeks to evaluate the current gaps by way of examining suicide and marriage using 44 years of datapoints. This includes the role of the exchange rate in suicide and marriage rates discourse, determining absolute suicide as a per cent of absolute marriage, and likely correlations between suicide, marriage and the exchange rate.

Materials and Methods: The data for this study were taken from various Jamaica Government Publications including the Demographic Statistics. The period for this work is from 1970 through to 2013. Data were recorded, stored and retrieved using the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, Version 21.0. The level of significance that is used to determine statistical significance is less than 5% (0.05) at the 2-tailed level of significance. Ordinary least square (OLS) regressions were used to determine models or factors of suicide rate.

Findings: For the studied period, the average marriage rate was 64.0 ± 21.4 per 10,000 (95% CI: 57.2-70.7) and 1.2 ± 0.8 per 100,000 for the suicide rate. The average marriage rate and suicide rate for the studied decades have been increasing constantly from the 1970s to 2000s. The largest percentage annual increase for both the suicide rate (220%) and marriage rate (70.1%) occurred in the 1990s over the 1980s. There was also a 25% and 20.1% rise in suicide and marriage rates respectively in the 2000s over 1990s. Furthermore, on average, 42 persons are married daily in Jamaica and approximately 3 persons commit suicide monthly.

Conclusion: The psychiatric and psychological disturbances in marriages are overlooked because of the established theories on the benefits of marriages. Suicide is an expression of marital discords which are allowed to fester for too long until divorce proceedings commence. Frequently, these unresolved issues often culminate with one party committing suicide.

Keywords

Marriage, psychiatric disorders, suicidal behaviour

Introduction

The matter of marriage has been extensively studied by many scholars including demographers, actuaries, psychologists and sociologists from the vantage point of mortality, life expectancy, benefits of spousal support, intimacy, happiness, psychological wellbeing and bereavement (Koo et al., 2004; Delbés & Gaymu, 2002; Smock et al., 1999; Moore et al., 1997; Goldman, 1993; Mateskaasa, 1992; Diener, 1984; Waring, 1980; Sheps, 1958). It is empirically established that marriage 1) increases life expectancy (Sheps, 1958), 2) is good for well-being (Wallis & Roberts, 1957; Brown, 1863; Waters, 1984; Ruggles, 1992; National Office of Vital Statistics, 1956), and 3) is more beneficial to men than women. Smith & Waitzman (1994) opined that men’s gains from marriage was greater than that of women (see also Lillard & Panis, 1996), and that “many observers have theorized that married individuals have access to more informal social support than do non-married individuals” (Smith & Waitzman 1994, 488).

Shurtleff (1956) opined that married people have a lower mortality than non-married people because they are healthier people.Such a perspective does not highlight the difficulty of maintaining a marriage and the mental health issues therein (Shrubb, 2013). Long before Shrubb’s research (2013), Daminian (1979) noted that there are stressors associated with marriages, including personality disorders, psychological disturbance and marital discords, that are not experienced by non-married people. Such perspective brings into focus a discourse of marriage and suicide.

All the aforementioned studies have not examined suicide, divorce and marriages. The matter of suicide and marital union was first studied from a sociological perspective by Emile Durkheim. Other scholars, even outside of sociology (Leach, 2000; Stack, 2000; Kposowa et al., 1996; Durkheim, 1897), have followed in his footsteps. In fact, Leach (2000) found that higher risks of suicides are found in divorces than marriages (RR = 2.08) and such findings support Durkheim’s work on suicide, which offers insight into this discourse. Leach (2000) and Durkheim (1897) opine that marriage has a preventative effect upon suicide and that it protects men from suicide, which would indicate that suicide is least committed by those who are in a marital relationship, making it good for well-being.

Cohen (2013), on the other hand, queries the inverse correlation between marriage and suicide, particularly among men. In his opinion, “the reason it’s a trick question is that, for older men suicide rates aren’t rising, even though their marriage rates are falling”, thereby questioning the established theory on the indirect relationship between marital unions and suicide, especially among men. The established theory on suicide and marriage supports a perspective that married people are least likely to have suicidal thoughts and even the question raised by Cohen has not refuted the theory. Psychologist, Bella DePaulo (2013), asked a similar question but research is yet to be done on the matter, post Emile Durkheim’s work, that has driven the theoretical framework for many studies on suicide.

Suicide rate in Jamaica is relatively low and Abel et al. (2009) conducted a secondary research, using data for 2002 to 2006 on suicide, which provides critical insight into the issue. However, Abel and colleagues did not examine suicide and marriage and so the discourse on the correlation between marriage and suicide is yet to be investigated in Jamaica. Another study revealed that direct correlation between suicide and marriage, but this was among women who are married against their will, forced marriages (Pridmore & Waller, 2013). In some forced marriages, women commit suicide as an option out of these marital arrangements and suicide increases in such instances (Arango, 2012). Such situations occurred in Iraq, India and other nations (Mayer & Ziaian, 2002; Pridmore & Waller, 2013; Arango, 2012), and cannot be used as the norm to establish a contradiction to Durkheim’s work and therefore a study of suicide in non-arranged marriages is still outstanding.

On examination of electronic databases such as MedLine, Psychoinfo, EbscoHost, ProQuest, no studies emerged that has examined suicide and marriage rates for a 44-year period; and includes the exchange rate in the discourse on suicide and marriage rate, as well as absolute suicide as a per cent of absolute marriage. The small number of absolute suicide in Jamaica (Thompson, 2014) is not enough evidence to warrant the absence of an investigation into the matter of suicide and marital status, particularly from the perspective of the gap in the literature on the matter. With Pridmore & Waller’s (2013) work indicating that most of those who commit suicide have some underlying psychiatric disorders, a few people who commit suicide are sufficient numbers to enquire into the matter, particularly among those who are married, as this will affect the children as well as society. Marriage is believed to confer psychiatric benefits (Ueker, 2012; Butterworth & Rodger, 2008) and this among other positives account for few studies that would have examined marriage and suicide. Daminian (1979) provides a rationale for the study of suicide and marriage by the perspective that psychiatric disturbance occurs among those in marital unions and that there are marital stressors that are related to psychiatric disorders. This study, therefore, seeks to fill the void in the literature by evaluating the current gaps through the examination of suicide and marriage rates using 44 years of datapoints; including the role of the exchange rate in suicide and marriage rates discourse and; absolute suicide as a per cent of absolute marriage, and the likely correlation between suicide, marriage and the exchange rate.

Econometric Model

Among the researchers who have used econometric analysis to the study of marriage and marital separation is Bourne and his colleagues. Using 64 years of panel data, Bourne et al. (2015) established factors that determined divorce, homicide and marriage. It is empirically established that marriage is a factor of the homicide rate and that maritial separation is influenced by macro-economic factors as well as divorce. Marriage is determined by macroeconomic and non-economic factors.

Dt = k + β1Popt + β2GDP per capitat + β3Ht [1]

Ht = k + β1Popt + β2Mt + β3Dt [2]

Mt = k + β1Popt + β2GDP per capitat + β3Nt + β4L [3]

For the current study, we forward that marriage rate is a factor of suicide:

St = k + β1MLtβ4L [4]

where:

Ht: indicates number of homicide events in time t

Popt: indicates the number of people in the population at time t

Mt: indicates the number of marriages that occurred in time t

Dt: denotes the number of divorces that were granted by the courts in time t

Lt: means the number of deaths that occurred and registered at time t

Nt: indicates the number of net international migrants in time t

MLt: represents the mortality rate per 10,000 in time t.

St: symbolizes suicide rate per 100,000 in time period t

k: denotes a constant

Materials and Methods

The data for this study were taken from various Jamaica Government Publications including the Demographic Statistics. Demographic Statistics provided data on mortality, population, and deaths. Jamaica Constabulary Force and Economic and Social Survey of Jamaica (ESSJ) provided the data for suicide; marriage, and the exchange rate of US $1 to the equivalent in Jamaica dollar. The period for this work is from 1970 through to 2013. Data were recorded, stored and retrieved using the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, Version 21.0. The level of significance that is used to determine statistical significance is less than 5% (0.05) at the 2-tailed level of significance.

Ordinary least square (OLS) regressions were used to determine models or factors of suicide rate. Prior to the use of the OLS, the researchers tested for normality of the variables (i.e., linearity and skewness including Durbin-Watson test). If a variable was that skewed (negatively or positively, Sk > ± 0.6), it would be logged to restore normality by way of natural logarithm (loge or ln). Hence, for this, none of the variables were logged because they had a skewness of less than 0.5. We also tested for the likelihood of Type I and Type II Errors, by using one-tailed and two-tailed test of significance. Data are compared across groups and in cases where there are missing data, analysis is done only in cases where all the data are available. In addition to the previously mentioned issues, the relationship between marriage rate and suicide rate was controlled for by homicide rate, carnal abuse and rape rate, and the exchange rate in order to determine the like association between marriage and suicide rate. For this paper, three hypotheses were tested – 1) weak positive statistical correlation exists between suicide rate per 100,000 and marriage rate per 10,000, 2) the exchange rate is a factor of the suicide rate, when marriage is entered in the same model, and 3) the relationship between suicide rate and marriage rate is nonexistent after controlling for by homicide rate, rape and carnal abuse rate and the exchange rate.

Reliability of the Data

A search of the statistical yearbooks (including Economic and Survey of Jamaica) reveals that Jamaica has been consistently collating and publishing suicide data since 1973 (Statistical Institute of Jamaica, 1973-1980; Planning Institute of Jamaica, 1976-2012); and marriage dates back to the 1950s. The police are responsible for collecting, vetting, reporting and resolving cases of suicide in Jamaica. Like Dominican Republic, Cuba and Puerto Rico, Jamaica has been consistenly reporting data on suicide; unlike the Englishspeaking Caribbean that has been doing so on an inconsistent basis (Abel et al., 2012; Nehall, 1991; Burke, 1985; Mahy, 1993; Abel & Martin, 2008).

Operational Definitions

Marriage: According to the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN), marriage is “The act, ceremony or process by which the legal relationship of husband and wife is constituted” (Statistical Institute of Jamaica, 1950-2013).

Mortality is the sum of deaths occurred within the population. According to Bourne et al. (2015) “The quality of mortality statistics in Jamaica is relatively good as research conducted by McCaw- Binns and her colleagues (1996, 2002) established that in 1997, the completeness of registration of mortality was 84.8%; in 1998 it was 89.6%. The quality of completeness of mortality registration has been established by the World Health Organization (WHO), ICD classification (Mather et al., 2005). A completeness of 70-90% is considered to be medium quality while more than 90% is considered high quality data. Within the context of the WHO’s classification, death statistics in Jamaica is medium quality and relatively close to being high quality. In keeping with the completeness of mortality data the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN) has adjusted the information to reflect the 100 completeness of mortality figures (Bourne, Solan, Sharpe-Pryce et al., 2014). GDP per capita is income per capita. Jamaica began collecting data on poverty since 1990 therefore; the model relating to poverty will be from 1990 to 2013” (Bourne, Solan, Sharpe-Pryce et al., 2014, p. 391).

Findings

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of average suicides and marriages for Jamaica based on four decades from the studied period of 1970-2013. For the studied period, the average marriage rate was 64.0 ± 21.4 per 10,000 (95% CI: 57.2-70.7) and 1.2 ± 0.8 per 100,000 for the suicide rate (95% CI: 0.9-1.5). The average marriage and suicide rates for the decades have been increasing at a constant rate from the 1970s to 2000s. The largest percentage annual increase occurred in the 1990s over the 1980s for both the suicide rate (220%) and marriage rate (70.1%), with a rise for suicide being 25% and 20.1% for marriage in 2000s over 1990s. Furthermore, on average, 42 individuals are married on a daily basis in Jamaica and approximately 3 persons commit suicide on a monthly basis. Detailed information on suicide and marriage can be viewed in the Annex.

| Detail | Mean±SD, 95% CI |

| Suicide rate (per decade): | |

| 1970s | 0.5±0.2, 0.3-0.7 |

| 1980s | 0.5±0.1, 0.4-0.6 |

| 1990s | 1.6±0.7, 1.0-2.2 |

| 2000s | 2.0±0.3, 1.7-2.2 |

| Marriage rate (per decade): | |

| 1970s | 44.7±2.7, 42.8-46.7 |

| 1980s | 42.5±5.7, 38.4-46.5 |

| 1990s | 72.3±20.0, 58.0-86.5 |

| 2000s | 86.8±8.5, 80.7-92.9 |

| Suicide rate per 100, 000 | 1.2±0.8, 0.9-1.5 |

| Marriage rate per 10,000 | 64.0±21.4, 57.2-70.7 |

| Daily absolute marriage | 42.2±17.7, 36.8-47.6 |

| Monthly absolute suicide | 2.5±1.9, 1.9-3.1 |

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics of Average Suicide and Marriage

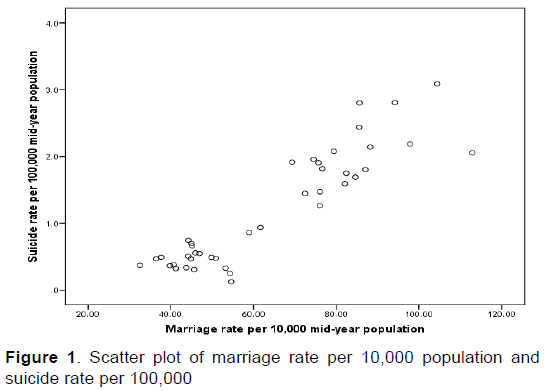

Figure 1 depicts a scatter plot of suicide rate per 100,000 midyear population and marriage rate per 10,000. Clearly there is a linear correlation between the two aforementioned variables.

Hypothesis

Null hypothesis 1: A weak positive statistical correlation exists between suicide rate per 100,000 and marriage rate per 10,000.

Marriage rate per 10,000 is a factor of suicide rate per 100,000. In fact, marriage rate per 10,000 was strongly correlated with suicide rate per 100,000 (F [1, 39] = 188.4, P < 0.000; rxy = 0.910; R2 = 0.829 or adjusted R2 = 0.824) – Table 2. We can extrapolate from this finding that a rise in the rate of marriage will correspond to an increase in suicide rate in Jamaica, suggesting that there are issues in social unions that are risk factors for suicide. Hence, we rejected the null hypothesis and therefore we can forward a linear equation that expresses the correlation between suicide rate and marriage rate – Eqn. [4]:

| Detail | Unstandardized Coefficients | Beta | t | P | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Lower-Upper | Zero-order | |||||

| Constant | -1.12 | 0.177 | -6.32 | <0.0001 | -1.5 - -0.76 | |||

| Marriage rate per 10,000 | 0.04 | 0.003 | 0.910 | 13.73 | <0.0001 | 0.03 - 0.04 | 0.910 | |

Table 2: OLS Regression Estimates of Marriage Rate per 10,000 on Suicide Rate per, 1970-2013

St = a + bMLt [4]

where a is a constant, b is the slope of the marriage rate per 10,000 and Mt is the marriage rate per 10,000 in time t and St is the suicide rate per 100,000 in time t.

Null hypothesis 2: The exchange rate is a factor of the suicide rate, when marriage is entered in the same model.

A positive statistical correlation existed between the exchange rate and suicide rate (rxy = 0.743). However, the exchange rate ceases to be statistically related with suicide rate, when marriage rate is entered therein (P = 0.139). Hence, the significant correlation between the exchange rate and suicide rate is a spurious one, which means that it is not a factor – Table 3.

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | P | 95.0% Confidence Interval | Relative Increase Variance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower | Upper | Zero-order | Partial | ||||

| Constant | -0.973 | 0.200 | -4.867 | 0.000 | -1.378 | -0.568 | ||||

| Marriage rate per 10000 | 0.032 | 0.004 | 0.800 | 8.196 | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.040 | 0.910 | 0.799 | |

| Exchange rate | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.148 | 1.512 | 0.139 | -0.001 | 0.009 | 0.743 | 0.238 | |

Table 3: OLS Regression Estimates of Marriage and Exchange Rates on Suicide Rate, 1970-2013

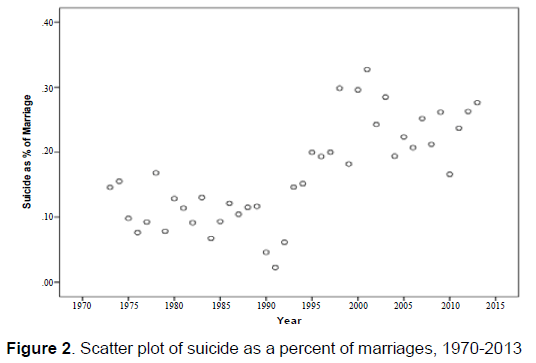

Figure 2 shows a scatter plot of suicide as a per cent of marriage in Jamaica, using data from 1970 to 2013. The figure showed that suicide as a per cent of marriage is a linear curve. This denoted that generally suicide as a per cent of marriage has been constantly increasing since the 1970s.

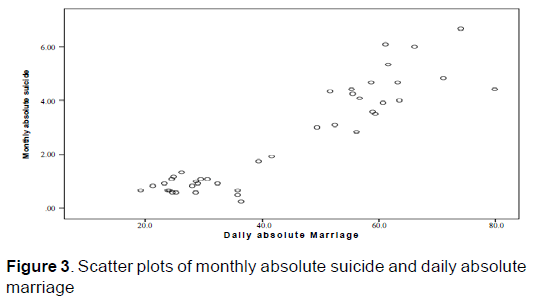

Figure 3 depicts a scatter plot of monthly absolute suicide and daily absolute marriage. The figure showed a clear positive linear relationship between the two aforementioned variables. This scatter plot was further examined using OLS regression. From the OLS regression, a positive statistical correlation existed between monthly absolute suicide and daily absolute marriage (b = 0.10), with the relationship being a strong one (rxy = 0.923; R2 = 0.851) - (F [1, 39] = 125.6, P < 0.0001, R2 = 0.851, Adjusted R2 = 0.847; Durbin Watson stat = 1.738) – Table 4.

| Details | Unstandardized Coefficients | Beta | t | P | 95.0% Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Lower | Upper | Zero-order | |||||

| Constant | -1.9 | 0.32 | -5.894 | <0.0001 | -2.5 | -1.2 | |||

| Daily absolute Marriage | 0.10 | 0.007 | 0.923 | 14.937 | <0.0001 | 0.087 | 0.115 | 0.923 | |

Table 4: OLS estimates of daily absolute marriage on monthly suicide, 1970-2013

Null hypothesis 3: The relationship between suicide rate and marriage rate is non-existent after controlling for by homicide rate, rape and carnal abuse rate and the exchange rate. The correlation between suicide rate and marriage rate was very strong even after controlling for by homicide rate, rape and carnal abuse rate, and the exchange rate (r = 0.785) – Table 5. Based on the P value (i.e. < 0.0001),we rejected the null hypothesis as relationship betweeen suicide rate and marriage rate remains even after controlling for selected variables.

| Control Variables | Suicide rate per100,000 | Marriage rate per 10,000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homicide Rate & Rape & Carnal Abuse Rate & Exchange rate | Suicide rate per100,000 | Correlation | 1.000 | 0.785 |

| Significance (2-tailed) | . | <0.0001 | ||

| df | 0 | 34 | ||

| Marriage rate per 10,000 | Correlation | 0.785 | 1.000 | |

| Significance (2-tailed) | <0.0001 | . | ||

| df | 34 | 0 | ||

Table 5: Pearson Correlations of suicide and marriage rate controlled for homicide, rape and carnal abuse and the exchange rate

Discussion

The challenges (or problems) in marital unions have been discusssed by Daminian (1979) who forwarded that there are marital stressors which are related to psychiatric disturbances. From Daminian’s perspective, it can be construed that there is a linkage between suicide and marriage (see also, Durkheim, 1897; Zhang, 2010; DePaulo, 2013). With suicide indicating psychiatric disorders and psychological disturbances, marital disruption is not the only reason for investigating suicide as there are mental health problems embedded in marriage that needs empirical inquiry. The psychiatric disorders and psychological disturbances are established in marital discord (Daminian, 1979; Olbrich & Bojanousky, 1981) and the extent of these are captured in the psychiatric hospitalization following divorce. Olbrich & Bojanousky (1981) discover that 50% of people who are married between 5 and 10 years are hospitalized within one year following the marital dissolution, which highlights the mental health problems associated with marital discord (Segraves, 1980).

Clearly, there are inherent problems in marital relationship that are hidden and become noticeable with legal separation or uxoricide. The majority of studies on marriages, mental health problems and suicide do not create the perspective that there are inherent problems in marriages. However, Shrubb (2013) indicates that there are mental health issues in marital relationship because of the difficulty in maintaining these unions. With Lillard & Panis’s findings that unhealthy men enter marriage at an early age and as such married men are not more healthier than non-married men (Lillard & Panis, 1996, 321, 322), it is imperative to examine marriage and suicide rates, using over four decades of data to provide critical insights to the discourse.

Over the last four decades from 1970 to 2013 in Jamaica, monthly suicide rises by 291% corresponding to a 31.3% increase in marriage over the same period. The largest percentage annual increase occurred in the 1990s over the 1980s for both the suicide rate (220%) and marriage rate (70.1%). Furthermore, on average, 42 people are married on a daily basis in Jamaica and approximately 3 people commit suicide on a monthly basis. Suicide rates in Jamaica are among the lowest in the world (Bertolote, 2001; Krug et al.,2002; Yang & Lester, 2004; World Health Organization, 2014a) but the current work showed that the rate of suicide has increased exponentially by 171% over 44 years, averaging 3.9% annually, and this is a cause for concern in all spheres, including public health. Such findings warrant an immediate inquiry into the marriage and suicide data. Based on Pompili and colleagues’ work (2010), there is an escalation in the number of suicide and this behaviour is a major health concern (see also, Wasserman et al., 2006; Bertolote, 2001) which is undoubtedly a public health problem that cannot go unnoticed any longer even in nations like Jamaica with a low suicide rate.

We found that suicide rate is substantially explained by the marriage rate (R2 = 83%), which implies that discords in marriages are expressing themselves in suicides. With the current findings showing that 83% of the variance in suicide rate, as well as monthly suicide, are explained by a 1% change in marriage rate or daily marriages, there are therefore psychiatric impairment that predates divorce. The psychiatric disturbance that is unfolding in marriages in Jamaica can be explained by Daminian’s work (1979). Daminian opines that psychiatric disturbances are related to marital stressors, which are associated with several psychiatric disorders in marriages. The fact that suicide rates were highly and positively related with marriage rate in Jamaica indicates that suicide is an expression of psychological disturbances and psychiatric disorders that are embedded in marriages but are rarely examined before legal separation. Although the literature widely establishes that marriages may confer mental health benefits (Uecker, 2012; Butterwoth & Rodgers, 2008; Segraves, 1980), there exists psychiatric disturbances that are outside of chance embodied in marriages, as is evident by this research and concurred with that of Daminian (1979).

There is a psychopathology to marriage that is unearthed with the advent of marital discords and people rarely focus on this prior to suicide and separation. While there are mental heath benefits to marriages as a result of shared economic resources and social support as is evident in the literature, there are some inherent marital stressors that exist and are rarely discussed empirically by research. Some of the disbenefits to marriages are highlighted here by way of this work as well as existing literature. Bourne et al.’s work (2014a) finds that 64.3% of Jamaicans who surpassed the life expectancy (females, 74 years; males, 71 years, using data for 2007) are non-married people. Another study by Bourne & McGrowder (2009) finds that 44.7% of those with chronic non-communicable diseases are married Jamaicans compared to 37.1% of non-married and 41.6% ages 60+ years. In reference to Bourne et al.’s earlier work (2014a) and Bourne & McGrowder’s study, we can deduce that while physical well-being of married people are greater than nonmarried people in Jamaica, the rate of death of married Jamaicans increases substantially before the life expectancy. Those facts clarify Sheps’ theory (1958) of the better health status of married people that this is not constant over the life course. As indicated in a research by Bourne (2009c), married people seek less health care with reluctance, possibly offering an explanation for mental health challenges because medical assistance is not sought in care of psychiatric and psychological disorders owing to the embedded challenges in the relationship.

Using Bourne & McGrowder’s study that married Jamaicans are healthier than non-married ones, and the fact that their mortality increases faster prior to the life expectancy than their non-married counterparts, we can deduce that the psychopathology of marriage is increasing the mortality rates. Clearly, psychiatric and psychological disorders erode some of the earlier stated benefits of marriage as emerged from the the current findings.The stressors in marriages are creating psychiatric and psycological disturbance which are expressed in terms of intimate partner violence, suicide and increased divorce rates. We can go further than previous studies that argued about the economics of suicide by forwarding that suicide is resulting from relationship inadequacies and personality disorders, especially in marriages. In a study of the poorest 20% of Jamaicans, Bourne (2009a) found that the majority were non-married (73%) compared to 19.8% of married people. Married people are benefiting economically from the partnership and so the discords in marriages would be outside of economic challenges. Married people, therefore, are experiencing psychological and psychiatric disturbances in silence and the earlier benefits of marriages are eroding over time.

The title of Butterworth & Rodgers (2008) study capsulates the challenges embedded in marriages, ‘Mental health problems and marital disruption: Is it the combination of husbands and wives’ mental health problems that predicts later divorces?’ Divorce is an indication of martial discords that existed in the marriage, and the legal separation is an expression of deepseeded psychiatric and psychological issues. A study shows that in 1950, there was one divorce on a daily basis and this rose to 7 in 2013 (Bourne et al., in print). From the exponential rise in suicide rates between 1970 and 2013 in Jamaica, suicide indicates marital disturbances and the difficulty in maintaining marriages. The prevention of suicide is a public health matter (WHO, 2014b) and rightfully because of the psychopathological issues that arise therefrom, and so keen attention must be placed in eyeing the challenges and conflicts in marriages before they lead to uxoricide. Outside of the pscyhopathological issues in divorce and suicides, Voracek (2009) opined that “Countries ranking high on suicide rates concurrently ranked high on national intelligence estimates, longevity, and affluence, whilst low on rates of births, infant mortality, HIV/AIDS, and crimes (rape, serious assault, and homicide)” (p. 733), thereby addressing the multiple modality of human existence.

Conclusion

The traditional perspectives that marital unions offer only optimistic psychosocial and psychiatric benefits to those involved are partially true as we can deduce from the current research that the positive benefits of marriages reside simultaneously with marital discords. The marital discords are permeating from the personal psychiatric and psychological disorders and these are silently creating personal, social and pscyhological turmoils among the spouses, which finally are expressed in legal separations. The clear reality is, there is a linkage between psychiatric impairment and marital discords but what is not spoken of are the internal challenges that are not visible in the marriages prior to dissolution.

References

- Abel, W.D., Bourne, P.A.,Hamil, H.K., Thompson, E.M., Martin, J.S., Gibson, R.C., et al. (2009). A public health and suicide risk in Jamaica from 2002 to 2006.North American Journal of Medical Sciences, 1(3), 142-147.

- Arango, T, (2012, June 6). Where arranged marriages are customary, suicides grow more common. New York Times.

- Baro, F. (1985).Psychosocial Factors and Health of the Elderly. United States:Pan American Health Organization.

- Bertolote, J.M. (2001). Suicide in the world: an epidemiological overview, 1959-2000. In: Wasserman, D., editor. Suicide-an unnecessary death. London: Bunitz, pp. 3-10.

- Bourne, P.A. (2009a). Health status and Medical Care-Seeking Behaviour of the poorest 20% in Jamaica. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health, 1(6&7), 167-185.

- Bourne, P.A. (2009b). Self-rated health and health conditions of married and unmarried men in Jamaica. North American Journal of Medical Sciences, 1(7), 345-352.

- Bourne, P.A. (2009c). Socio-demographic determinants of Health care-seeking behaviour, self-reported illness and Self-evaluated Health status in Jamaica. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health, 1(4), 101-130.

- Bourne, P.A., & McGrowder, D.A. (2009). Health status of patients with self-reported chronic diseases in Jamaica. North American Journal of Medical Sciences, 1(7), 356-364.

- Bourne, P.A., Hudson-Davis, A., Sharpe-Pryce, C., Clarke,J., Solan, I., Rhule, J., et al. (2014b). Does Marriage Explain Murders in a Society? In What Way is Divorce a Public Health Concern?International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience, 16(2), 84-92.

- Bourne, P.A., Hudson-Davis, A., Sharpe-Pryce, C., Lewis, D., Francis, C., Solan, I., et al. (in press). The psychology of homicide, divorce and issues in marriages: Mental health and family life matters. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience.

- Bourne, P.A., Solan, I., Sharpe-Pryce, C., Campbell-Smith, J., Hudson-Davis, A., Watson-Coleman, O., Rhule, J. (2014a). Living Beyond the Life Expectancy: A self-Rated Health Viewpoint. Journal of Gerontology & Geriatric Research, 3, 153.

- Brown, S.(1863). On the Rate of Mortality and Marriage amongst Europeans in India.The Assurance Magazine, and Journal of the Institute of Actuaries, 11(1), 1-39.

- Butterworth, P. & Rodgers, B. (2008).Mental health problems and marital disruption: Is it the combination of husbands and wives’ mental health problems that predicts later divorces? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(9), 768-763.

- Cohen, P. (2013, May 24). The link between marriage rates and suicide is questionable. The Atlantic.

- Daminian, J. (1979). Marriage and psychiatric illness.British Medical Journal, 2(6194), 854-855.

- Delbés, C. & Gaymu, J. (2002).The shock of widowed on the eve of old age:Male and female experience. Demography, 3, 885-914.

- DePaulo, B. (2013). Are married people less likely to kill themselves? Suicide protection: another myth about marriage bites the dust. Psychology Today.Sussex Publishers.

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective wellbeing. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 3, 542-575.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M.E.P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science,13, 81-84.

- Durkheim, E. (1897). Suicide: a study in sociology. The Free Press: New York.

- Elwert, F., & Christakis, A. (2006).Whites more likely than blacks to die soon after spouse's death.Harvard’s Research Matters Website. Retrieved from: http://www.researchmatters.harvard.edu/story.php?article_id=1036

- Goldman, N. (1993).Marriage selection and mortality patterns:Inferences and fallacies. Demography, 30, 189-208.

- Koo, J., Rie, J., & Park, K. (2004).Age and gender differences in affect and subjective well-being.Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 4, S268-S270.

- Kposowa, A.J., Breault, K.D. &Singh, G.K. (1996). White male suicide in the United States: a multivariate individual-level analysis. Social Forces,74, 315-323.

- Krug,E.G., Dahlberg, L.L., Mercy, J.A., Zwi, A.B., & Lozano, R. (2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Leack, A.P. (2000). Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study.Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 54, 254-261.

- Lee, G.R., Seccombe, K., & Sehehan, C.L. (1991).Marital status and personal happiness:An analysis of trend data.Journal of Marriage and the Family,53, 839-844.

- Lillard, L.A., & Panis, C.W.A. (1996).Marital status and mortality:The role of health.Demography,33, 313-327.

- Mastekaasa, A. (1992).Marriage and psychological well-being: Some evidence on selection into marriage.Journal of Marriage and the Family,54, 901-911.

- Mayer,P., & Ziaian, T. (2002). Indian suicide and marriage: A research note. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 33(2), 297-305.

- Moore, E.G., Rosenberg, M.W., & McGuinness, D.(1997).Growting old in Canada: Demographic and geographic perspectives.Ontario, Canada:Nelson.

- National Office of Vital Statistics, USPHS (May 8, 1956).Mortality from selected causes by marital status - United States, 1949-1951.Vital Statistics-Special Reports, 39(7), 303-429.

- Olbrich, D. & Bojanousky, J. (1981).Psyhiatric hospitalization of divorced person. Psychiatric University Clinics(Basel), 14(1), 56-65.

- Pompili, M., Serafini, G., Innamorati, M., Dominici, G., Ferracuti, S., Kotzalidis, G.D., et al. (2010). Suicidal behavior and alcohol abuse. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(4), 1392-431.

- Pridmore, S., & Waller, G. (2013).Suicide and forced marriage. Malaysian Journal of Medical Science, 20(2), 47-51.

- Ruggles, S. (1992).Migration, marriage, and mortality: correcting sources of bias in English Family Reconstitutions. Population Studies, 46, 507-522.

- Segraves, R.T.(1980). Marriage and mental health. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 6(3), 187-98.

- Sheps, M.C.(1958). Shall we count the living of the dead.The New England Journal of Medicine,259(25), 1210-1214.

- Sheps, M.C. (1961). Marriage and mortality.American Journal of Public Health, 51(4), 547-555.

- Shurtleff, D. (1956). Mortality among the Married.Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 4, 654.

- Smith, J.C., Mercy, J.A., Conn, J.M. (1988). Marital status and the risk of suicide.American Journal of Public Health, 78,78-80.

- Smith, K.R., & Waitzman, N.J. (1994).Double jeopardy:Interaction effects of martial and poverty status on the risk of mortality.Demography,31, 487-507.

- Smock, P., Manning, W.D., & Gupta, S. (1999).The effects of marriage and divorce on women’s economic well-being. American Sociological Review,64, 794-812.

- Spurgeon, E.F. (1922) Life Contingencies.Cambridge University Press.

- Stack, S. (2000). Suicide: A 15-year review of the sociological literature part I: Cultural and economic factors. Suicide and Life-Threatening behavior, 30(2), 145-162.

- Thompson, K. (2014, September 10). Jamaica’s low suicide rate no reason to celebrate, warns counsellor. Kingston: Jamaica Observer.

- Uecker, J.E. (2012). Marriage and mental health among young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(1), 67-83.

- Umberson, D. (1987). Family status and health behaviors: Social control as a dimension of social integration. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,28, 306-19.

- Voracek, M. (2009). Suicide rates, national intelligence estimates, and differential K theory.Perceptual and motor skills, 109(3), 733-6.

- Wallis, W.A., and Roberts, H.V. (1957).Statistics.A new approach. Glencoe, Illinois: Free Press.

- Waring, E.M. (1980). Marital intimacy, psychosomatic symptoms, and cognitive therapy. Psychosomatics, 21, 595-601.

- Waring, E.M., McElrath, D., Lefcoe, D., & Weisz, G. (1981). Dimensions of intimacy in marriage. Psychiatry, 44 ,169-177.

- Wasserman, D., Cheng, Q., &Jiang, G.X. (2006).Global suicide rates among young people aged 15-19. World Psychiatry, 5(1), 39.

- Waters, H.R. (1984). An approach to the study of multiple state models.Journal of the Institute of Actuaries, 111, 363.

- Wilkie, A.A. (1988). Markov Model for combined marriage and mortality tables.Presented to the 23rd Congress of International Actuarial Association, Helsinki.

- World Health Organization. (2014a). Health statistics and information system. Geneva: WHO.

- World Health Organization. (2014b). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. Geneva: WHO.

- Yang, B., & Lester, D. (2004). Natural suicide rates in nations of the world, Short report. Crisis, 25, 187-188.

- Zhang, Z. (2010).Marriage and suicide among rural young women. Social Forces, 89(1), 311-326.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16072

- [From(publication date):

specialissue-2015 - Jul 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11428

- PDF downloads : 4644