Review Article Open Access

Sts’ailes Mental Wellness Clinic: Description of the First 15 Months of a Service Development Journey on a St’olo First Nation in British Columbia, Canada

Benning TB1*, Hamilton M2, Isomura T3,4, Kuperis S3, Mussell B5, Noizadan S2 and Peters V51Maple Ridge Mental Health Centre, British Columbia, Canada

2Sts’ailes Health and Family Services, Canada

3Department of Mental Health and Substance Use, Fraser Health, Canada

4Sherbrook Centre, Royal Columbian Hospital, New Westminster, Canada

5Sal’I’shan institute, Chilliwack, Canada

- *Corresponding Author:

- Tony B Benning

Consultant Psychiatrist, Maple Ridge Mental Health Centre, Dewdney Trunk Road

Maple Ridge, 500 22470, British Columbia, V2X 5Z5, Canada

Tel: 604-476-7165

Fax: 604-476-7199

E-mail: tony.benning@fraserhealth.ca

Received date: May 17, 2017; Accepted date: June 05, 2017; Published date: June 10, 2017

Citation: Benning TB, Hamilton M, Isomura T, Kuperis S, Mussell B, et al. (2017) Sts’ailes Mental Wellness Clinic: Description of the First 15 Months of a Service Development Journey on a St’olo First Nation in British Columbia, Canada. J Community Med Health Educ 7:525. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000525

Copyright: © 2017 Benning TB, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

The Sts’ailes community is a First Nation close to Chilliwack in British Columbia, Canada where a mental wellness clinic was launched in January 2015. Presented here, in addition to description of the development and structure of the clinic are the sources of referral, demographics, diagnoses and other characteristics of all patients seen over a 15 month period (January 2015 to April 2016). By way of context, the paper begins with an overview of the cultural and historical background of Sts’ailes. It then describes the health services that were in existence at Sts’ailes prior to the mental wellness clinic as well as the values that were held to be important for the mental wellness clinic to embody. Emphasized in this paper too is the fact that a significant time period of consultation and relation-building as well as organizational commitment between First Nations representatives as well as representatives of the local health authority preceded the inception of the clinic.

Keywords

Indigenous mental health; Psychiatry; Traditional healing; Integrated models of service delivery; Cultural safety

Introduction

Cultural and historical background

The term Stalo or St’olo (translated from the Halkomelum language as “people of the river”) refers to indigenous people “living along the lower 105 miles of the Fraser River” [1]. St’olo constitutes a very small subset of the larger category Coast Salish , an all-encompassing reference to the Pacific Northwest’s indigenous peoples. Sts’ailes, geographically located along a stretch of the Harrison River in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley, close to Harrison Lake, constitutes one of the St’olo groups or “tribes” [1]. An estimated 560 of the present Sts’ailes membership live on reserve and 1500 or so off reserve.

Oral accounts as well as written ethnographic monographs attest to the centrality of traditional ceremonial practices to the social life of the Sto’lo peoples. And what is clear, in keeping with many indigenous practices worldwide, is that those ceremonial practices, whether they be a sweat ceremony [2] or winter spirit ceremonies [1] simultaneously perform healing as well as religious and social functions.

No history of any Canadian First Nation would be complete without reference to the subjugation that took place at the hands of colonial authorities. A pertinent example of that is the infamous “Potlach ban”. This refers to the third section of the Indian Act, signed in 1884, which made it illegal for indigenous people to engage in Native ceremonial practices [3]. In fact, one of the authors of this paper (Peters) has personal experience of life under those conditions of colonial oppression and can attest on the basis of her own experience to the fact that a cloud of fear hung over communities such as Sts’ailes for more than a decade even after the Potlatch ban was finally lifted in 1951. It was not until the 1970s that there emerged a renewed sense of confidence as well as cultural identity on the part of Coast Salish communities and that time, a revival of indigenous ceremonial practices including the winter spirit ceremonies was seen. Rich ethnographic descriptions of the ceremonial practices can be found in Duff’s [1] The Upper Stalo Indians of the Fraser Valley, British Columbia and Barnett’s [4] The Coast Salish of British Columbia. And discussion of their potential “therapeutic” potential can be found in Wolfgang Jilek’s [5] excellent study Indian Healing. A prolific clinicianresearcher and author, Jilek also authored other papers [6-10] examining the therapeutic possibilities of local indigenous ceremonial practices in psychiatric conditions and it is a source of bewilderment −to say the least−why this area should not have received any further scholarly attention for the subsequent 40 or more years (Figure 1).

From cultural competence to cultural safety

Inordinately high rates of mental illness, substance abuse, and suicide among Aboriginal Canadians are an established fact. But the need, in Aboriginal communities, for mental health services that are culturally competent, is increasingly recognized. The lack of that attribute in mainstream mental health services has been posited by many [11,12] to be a major reason for the underutilization of mainstream mental health and psychological services by Aboriginal peoples.

What does it mean to be culturally competent? First, mental health services ought to be cognizant of the etiological relevance of such socio-historical factors in the genesis and perpetuation of psychiatric morbidity as colonization, historical trauma, residential schools, forced assimilation [13] and so forth. There needs to be an awareness of Aboriginal explanatory models of illness too. Those may not view mind and body as ontologically distinct [14,15], they may countenance supernatural causal attributions [15,16] and, it is not at all unusual in indigenous cultures for proximal and remote factors to be co-existent in conceptualizations of disease causation [17]. The latter may be anathema to the sort of reductionist biomedical models of disease causation that have come to all but dominate Western psychiatric discourse in recent decades. Mental health services should also be aware of Aboriginal conceptualizations of and approaches to healing −in which place and space are held to have much therapeutic significance [18] and in which spirituality [19], ceremonial practices, cultural continuity and connectedness [20-22] are posited as having intrinsically positive value, as therapeutic resources.

The emergent concept of “cultural safety” has come to occupy an important place in contemporary Aboriginal wellness discourse. It is a concept that builds on and extends the concept of cultural competence but, as Brascoupé et al. [23] wrote, it emphasizes the risks associated with the absence of cross-cultural awareness and sensitivity. The same authors acknowledged that while cultural competence and cultural safety lie on the same continuum of cultural considerations, the latter concept has a more overtly politicized and radical connotation and is, as such, in tune with issues around power, difference and selfdetermination. One of the pragmatic implications of the concept of cultural safety, in terms of service delivery and development then, is the imperative of redistributed power away from the service provider and towards the service recipient(s), both at individual and organizational levels.

Relationship-Building and Mutual Organizational Commitments

Sts’ailes and other First Nations close by are served by the Fraser Health Authority, one of Canada’s largest health authorities−serving a total population of 1.6 million residents. Of those, approximately 38000 are of First Nations background. In December, 2011, the Fraser Health executive and leaders of local First Nations communities signed the Health Partnership Accord [24], the purpose of which was to articulate a vision for future collaboration. Central to that vision was a commitment to blending “the best of two worlds in health−modern medicine and ancestral teachings and ways of knowing”. The health partnership accord paved the way for the development of health services−as collaborative endeavours−between the Fraser Health Authority and Fraser Salish communities. The partnership accord was followed by the formation of a steering committee, the primary goal of which was to develop mental wellness and substance abuse services in Fraser Valley’s indigenous communities.

The priorities of the Aboriginal steering committee were:

• To ensure a person-centred experience of care through holistic, integrated, high quality, and accessible health services that are sensitive to cultural diversity

• To promote and support mental wellness and prevent substance abuse harms in a range of settings including communities, schools, workplaces, and care facilities

• Incorporate First Nations perspectives on wellness

• Strengthen the role of traditional healers and medicines

• Continued collaboration with Fraser Health Authority and First Nations Health Authority with intention of implementing commitments enshrined in the partnership accord.

Initiatives in the Fraser Valley prior to Sts’ailes

Prior to the signing of the 2011 partnership accord, a consultation process between Fraser Health and the town of Boston Bar band began in 2009. That particular consultation process culminated in the creation of a primary care clinic at Anderson Creek. As well, an initiative at Seabird Island was launched in January 2013 in which a psychiatrist, concurrent disorders therapist and Aboriginal health liaison started to work closely with Seabird Island’s existing healthcare team. Seabird Island was also the lead community for a region wide collaborative endeavour on suicide prevention, intervention and postvention.

Building relationships at Sts’ailes

Although the clinic at Sts’ailes was launched in January 2015, this was preceded by a period of a year or so during which several meetings took place between key people from Sts’ailes (the Sts’ailes mental wellness committee) and Fraser Health authority. Mutual learning and knowledge exchange took place during those meetings and a shared vision and values for the wellness clinic were agreed upon and crystallized. There were also discussions of existing services at Sts’ailes and the nature of ongoing needs that had been identified. Considerable time was also devoted to discussing the values that a mental wellness clinic should embody. Those values were outlined in a memorandum of understanding, the major elements of which will be outlined in the next section.

Sts’ailes: Existing services, needs and values

A key document Sts’ailes Primary Healthcare Project Report [25] presented the findings of 6 year collaboration between Sts’ailes, the Fraser Health Authority and researchers from the Universities of Victoria (UVic) and British Columbia (UBC). On the basis of extensive literature review of Aborginal community mental health centers in Canada and abroad as well as interviews with participants at Sts’ailes, this comprehensive document made a series of recommendations regarding the development and implementation of community-based health services at Sts’ailes. This document emphasized the integration of Western medicine and indigenous/traditional healing, involvement of elders in service development, the need for culturally appropriate and culturally relevant services, acknowledgement of history, and a non-hierachical staff structure. Emphasised too was the importance of a strengths-based service and one that is capable of responding to individuals’ health needs in a timely fashion.

On the heels of Bakula and Anderson’s report, Sts’ailes Chief and Council, in 2014, issued a directive to align health services with those of Snowoyelth (Children and Family Services, including Child Protection), the two main goals of which were

• The development of an integrated system which will strengthen the ability of service providers to meet the needs of individuals and families challenged by Mental Health and/or addictions issues. It was agreed that while there are multiple opportunities for like services to be integrated, Mental Health is identified as the most urgent.

• That service providers across Health and Snowoyelth would now work with Lets’mot (one Heart, one Mind and one Spirit).

An immediate response to that directive was the creation of a mental wellness committee. One of the objectives of that committee was to develop a system with flexible points of entry for clients, regardless of circumstance. Another objective was to ensure an integral role−within the circle of care−for the 10 cultural counselors that were already working at Sts’ailes. Incidentally, just 2 of those had special training in the addictions field. The third objective was to recruit a psychiatrist. The need for a psychiatrist had particularly come to light by the community’s experience of having difficulties accessing mental health services for several young people suffering from psychosis. The mental wellness committee undertook, then, to partner with Fraser Health Authority to bring about the realization of a vision to have a visiting psychiatrist at Sts’ailes. During the series of meetings that took place between January 2014 and January 2015, a memorandum of understanding was formulated in which the following guiding values were articulated.

• Indigenous knowledge provides a window to understanding the Sts’ailes health and wellbeing related to mental wellness and substance abuse. Sts’ailes and Fraser Health MHSU recognize the value of different bodies of knowledge and differing ways knowing and are committed to respecting multiple perspective and blending various bodies of knowledge and traditions

• Sts’ailes community Elders have a key and central role beyond a symbolic presence in establishing mental wellness and substance use services in the community

• Sts’ailes and Fraser Health MHSU commit to forming partnerships of caregivers which includes Traditional and Spiritual Healers, Physicians, Psychiatrist, nurses and other health care providers to support the mental wellness and address substance use within the current established Sts’ailes primary health care model

• Sts’ailes and Fraser Health MHSU services shall share the following service values in the delivery of services; love, respect, courage, honesty, wisdom, humility and truth as defined in: A Path Forward ‘(BC First Nations and Aboriginal People’s Mental Wellness and Substance Abuse Use 10 year Plan).

One of the meetings took place over a half-day period and incorporated a range of briefings undertaken by various members of the Sts’ailes community. They included a visit to one of the longhouses (smokehouses) where an overview was provided by a community leader on history of Sts’ailes and surrounding areas as well as aspects of the spiritual and cultural life of its members. That particular meeting helped to consolidate a sense of collective commitment to the launch of the mental wellness clinic.

The Mental Wellness Clinic: Core Values and Guiding Principles

The concept of “indigenous culture as mental health treatment” [26] has gained much currency in recent years. It maintains that practices and processes that reinforce cultural connectedness, continuity, and identity themselves have intrinsic healing potential. Developing that idea, several commentators have advocated for integrated models of healing that effectively combine Western and indigenous approaches −especially in the area of mental wellness [25-32].

In an attempt to explore the scope of collaborative approaches available to psychiatrists working with indigenous populations, Benning [32] described a framework of deep collaboration within which to envisage the relationship between psychiatry and traditional ways of knowing. Deep collaboration is entirely consistent with the concept of “two-eyed seeing” [33] in so far as it aims to reconcile distinct worldviews and ontologies. As such, deep collaboration aims to position psychiatry and traditional paradigms on a radically equal footing in which each respects the other and in which neither seeks to monopolize the healing narrative or deprecate the ontological premises of the other.

From the outset then, a commitment to deep collaboration was identified as a core value and a fundamental guiding principle in the Sts’ailes mental wellness clinic. As well, we were mindful of the complex nature of indigenous spirituality and its resulting resistance to being reduced to simple sound-bites or being construed merely as a set of “practices”. That very point was articulated by Adelson [34] when she wrote that “sweat lodge, healing circles, and pipe ceremonies…” represent only “the more visible elements of a far more complex, integrated, and holistic spiritual belief system”.

We were also aware of the existence of other contemporary mental health services in Canada that had been attempting to integrate Western and indigenous approaches to mental wellness. They include the Six Nations Mental Health Services in Southwestern Ontario, a service that has been running since 1997 [35,36] and an integrated mental health clinic on Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron, Ontario [13,37]. However, in those publications, we were not able to find descriptions of referral pathways, waiting times, numbers of patients seen, patient demographics, diagnoses and so forth. That gap in the existing literature sensitized us to the importance of assiduous documentation from the outset as well as acquisition of qualitative as well as quantitative data.

Structure and processes of clinic and demographic data

Patients were seen by the visiting psychiatrist (Benning) on alternate Fridays in a building which was originally built to house health services for elders at Sts’ailes. That building is located at Sts’ailes adjacent to the main administrative buildings and band office (Figures 2 and 3).

The psychiatrist sometimes saw patients alone but more often than not patients were seen with a registered nurse, an employee of Sts’ailes (Noizadan). Especially vital roles played by the nurse included coordinating referrals, scheduling appointments, assisting with data collection, and liaising between psychiatrist and patient outside of clinic hours. During the 15 month period, the psychiatrist and nurse (neither of whom are of Aboriginal ancestry) gladly accepted an invitation to participate in a sweat lodge ceremony with one of the traditional healers. In addition to the fact that the nurse and psychiatrist had a genuine interest in doing so, that sort of participation is very much in keeping with the recommendations made in a 2010 document published by the indigenous physicians association of Canada [38] in which it was suggested that non- Aboriginal physicians gain some familiarity with traditional healing rituals and ceremonies. In addition, the psychiatrist and nurse were visited on 2 occasions by different traditional healers in which knowledge exchange and discussion of criteria for referral criteria and referral pathways were undertaken. Potential ideas for future collaboration were discussed too. As well, at 3 month intervals, meetings took place involving a senior administrator/director from the Fraser Health Authority (Kuperis), former chief of psychiatry in Fraser Health Authority (Isomura), the visiting psychiatrist (Benning), the nurse (Noizadan) and members of the Sts’ailes mental wellness committee (Hamilton and Peters). The purpose of those meetings was to share knowledge about the progress of the clinic, to identify and resolve administrative glitches and to foster a sense of collective purpose.

Patient demographics and diagnoses

In the 15 month period (January 30th to April 30th, 2015) 23 new patient (M=15; F=13) evaluations occurred and there were 57 (M=30; F=27) follow up appointments. The youngest patient seen was 15 and the oldest, 63. The mean age of all patients seen was 35. 22 out of the 23 patients were seen within 2 weeks of the initial referral and 1 patient was seen within 4 weeks of the referral. A total 19 of the 23 patients seen were referred by a visiting family physician at Sts’ailes. Referrals also came from other GPs in the Chilliwack area, an Emergency room physician at Chilliwack General Hospital and a nurse practitioner at Sts’ailes.

The most represented diagnostic category was major depression, with twice as many women than men meeting the DSM V [39] criteria at initial evaluation (Figure 4). Other highly represented categories included unspecified depressive disorder and substance use disorder.

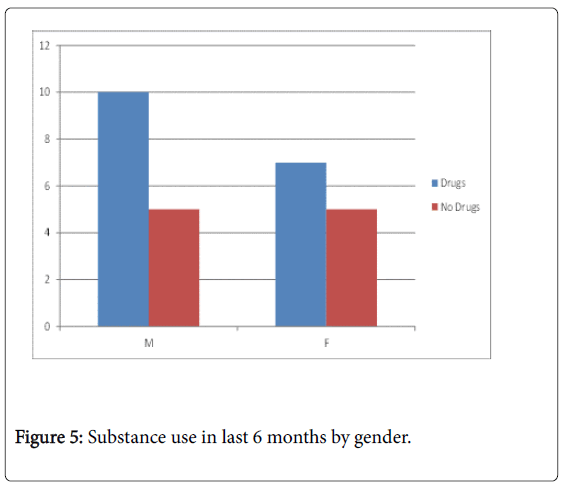

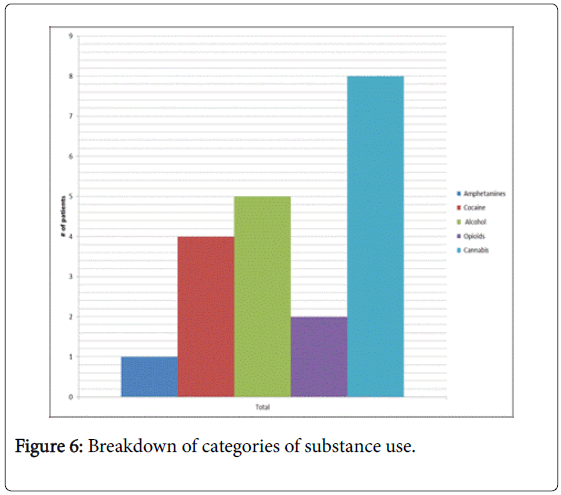

In the case of both males and females, more patients than not had used at least one category of psychoactive substance in the last 6 months (Figure 5). The most commonly used substance was cannabis followed by alcohol and then by cocaine, as is depicted in Figure 6.

The issue of diagnosis

Health and wellness literature [27,40] as well as anecdote behooves caution on the part of clinicians when it comes to delivering psychiatric diagnoses to First Nations Peoples. The reasons for that encompass a concern that psychiatric diagnoses contribute to stigma, and that, as Western constructs, they impose Western worldviews on indigenous peoples. While the American Psychiatric Association’s official stance regarding diagnoses is that they are atheoretical, which is to say that no assumptions are made about etiology, the reality is that Western psychiatric discourse is replete with assumptions about the aetiology of most psychiatric conditions. Those assumptions invariably hold the major mental illnesses to be underpinned by a chemical deficit or neurophysiological aberration of some sort.

The major psychiatric disorders then (schizophrenia, PTSD, depression, anxiety) each carry with them an ensemble of meanings that encompass certain ideas about etiology. Modern psychiatry’s proclivity for locating pathology “in the brain” leads to a massive under-appreciation of the pathogenic role of socio-cultural factors in mental illness. Just consider the vast literature that implicates sociocultural factors in the causation and perpetuation of schizophrenia, one that gets all but sidelined in the contemporary neuro-scientific psychiatric discourses. It is precisely because of those sorts of concerns that some commentators have called into question the very legitimacy of the concept post-traumatic stress disorder [41,42]. The term Historical trauma [26,43-45] is arguably more suitable in indigenous communities because it redeploys the diagnostician’s gaze−so to speak −on to the socio-cultural level instead of the merely neural one. So what are the practical implications of this when working with indigenous people, especially at Sts’ailes? Pragmatism dictates that one cannot entirely dispense with conventional psychiatric diagnoses when working with First Nations people. Sts’ailes is no more isolated from the administrative processes of the wider society than are other First Nations. This is to say that applications for disability, letters to employers, insurance companies and so forth remind us of the indispensability of a “diagnosis” in various administrative and beaurocratic transactions. But that aside, a diagnosis, if delivered in the right way, can be just as therapeutic and psychologically important for an indigenous person as for anyone else. In fact Torrey et al. [46] reminded us in Witchdoctors and Psychiatrists: The common roots of psychotherapy and its future that the naming of an illness is a universal practice, common to almost all healing systems, cross-culturally. But in practice, presenting a diagnosis in overly reifying terms should be avoided. That is to say that diagnoses should presented in tentative terms, care should be taken to insure that the diagnostic label not be conflated with patient’s identity [27] and it should not detract from the task of facilitating the patient’s own narrative [47-49]. An overly reifying and staticizing use of diagnostic terms-in addition to being stigmatizing−is incongruent with the process-oriented characteristics of indigenous cosmologies and conceptualizations of mind [50].

Spiritual and Cultural Practices Questionnaire (SACPQ)

A special point was made to incorporate the following questions in to the initial psychiatric history the purpose of which was to identify individuals’ extent of experience and/or interest in indigenous or other spiritual practices.

• Are you (have you been) involved in any spiritual practice (such as sweat lodges, winter ceremonies, spiritual baths, other)?

• If “Yes”,

• Which?

• More/less than 6 months ago?

• Was it helpful?

• How and why?

• Are there any conflicts between Western treatments and traditional/spiritual practices from your perspective?

• Are you (have you been) involved in any spiritual practice?

• If “no” - Would you like to be involved?

• If “Yes” - Do you perceive any barriers? Do you perceive any conflict between Western treatments and traditional/spiritual practices?

Some of the information acquired as a result of the SACPQ is presented in the following short vignettes:

Case vignette 1

A 33 year old lady suffered from major depression and alcohol use disorder. She disclosed that she had been a spiritual dancer in the winter long house ceremonies for several years. She reported that the ceremonies invariably help with depression for they make her feel “uplifted and cleansed”. Further, she refrains from consuming alcohol during several months in the winter. She agreed to take antidepressants reporting no “conflict” between doing so and participating in traditional ceremonies.

Case vignette 2

A 16 year old boy referred on account of low mood, recurrent selflacerations and cannabis consumption. By the time he was referred to us he was already much better. He attributed this in large part to that fact that he had taken up canoe pulling-something that he understood not only as a spiritual practice, but as exercise, and a vehicle for strengthening of cultural identity.

Case vignette 3

A 18 year old with schizophrenia has been a spiritual dancer in the long house for 5 years. He spoke in the following positive terms about his experience in the long house: “It’s good to be around family members… I like the spiritual teachings; they make me think clearly…. I also like doing the work; cleaning and getting wood”

Case vignette 4

A 40 year old suffering from social anxiety disorder and depression. He did agree to a trial of escitalopram 10 mg but also spoke of the benefits of having taken part in a sweat ceremony 2 weeks earlier to which he attributed now feeling “very comfortable and free of anxiety”. He also spoke positively about a Pow Wow that he attended recently “It’s hard not to be happy in that environment”

Discussion

This paper has emphasized the fact that the inception of the mental wellness clinic at Sts’ailes was made possible by a mutual organizational commitment to delivering collaborative health services. Our contention is that such commitments at an organizational level are absolutely crucial in as much as they create an infrastructure for future collaboration whose survival ought not to be contingent on the efforts of specific individuals, no matter how committed those individuals might be. Furthermore, in keeping with Gone’s [26] observation, we contend that the promotion of traditional approaches to healing serves to assert indigenous cultural heritage and identity, and as such cannot be considered in isolation from wider political imperatives. To the contrary; what we may refer to as the “semiotic significance” of traditional healing runs the entire gamut between the political and the personal.

The admission criteria for acceptance in to the clinic were not as stringent as are those in mainstream community mental health centres. The advantage of that was that our clinic was able to address psychiatric morbidity associated with such conditions as traumatic brain injury, grief, ADHD, and unspecified depressive disorder, all conditions that generic community mental health centers in Canada would not generally consider falling within their remit. The high prevalence of substance misuse in our patient series is consistent with the findings in several Aboriginal communities across Canada [51,52].

The spirituality and cultural practices questionnaire helped to ascertain information about spiritual activities or practices that patients were already involved in or were interested in being involved in. The questionnaire honored the principle that predetermined assumptions about the nature of individuals’ worldviews or cultural affiliations [53] should be avoided. The SACPQ greatly facilitated the psychiatrist’s (Benning) learning about the diverse range of worldviews embraced by Sts’ailes community members, worldviews that encompassed a range of positions: secular, Christian only, Christian and native spirituality, native spirituality only, other indigenous (such as sun dance ceremony), devotion to the shaker faith and so forth. This heterogeneity of worldviews alludes to the complex relationship between Christianity and Native spirituality in the postcolonial Canadian indigenous context, something that is brilliantly elaborated by Adelson [34] in her essay Toward a Recuperation of Souls and Bodies: Community Healing and the Complex Interplay of Faith and History.

The spirituality and cultural practices questionnaire also yielded helpful information about the barriers that patients perceive to be preventing them from having greater access to spiritual resources. Those barriers included, in some cases, concerns about privacy and confidentiality. In some cases the barrier was a pragmatic and logistical one of simply not knowing whom to ask to gain access to long house ceremonies or sweat lodge ceremonies etc. Regarding the possible perception of conflict between Western psychiatry and traditional approaches to healing, we acknowledge a self-selection bias which is to say those perceiving a conflict were likely not to have made it to the clinic in the first place. Nonetheless, it was noteworthy that only one of our patients disclosed a conflict of that sort. She was a lady in her 50s, suffering from a new onset psychosis. Wanting only traditional treatments, she alluded to the existence of conflict. Very reluctantly and with a great deal of ambivalence, she attended the clinic on only two occasions and declined to attend after that.

Conclusion and Future Directions

This paper has described the process of development and general structure of a mental wellness clinic at Sts’ailes, a St’olo Nation near Chilliwack in British Columbia, Canada. The clinic has led to improved access to mental health services for members of the Sts’ailes community. In addition to having succeeded in being responsive the clinic has demonstrated a commitment to delivering a culturally appropriate service, and the concept of deep collaboration [32] is in strong alignment with that commitment. This is to say that there is an interest on the part of the Sts’ailes leadership as well as the psychiatrist and other mental health professionals, in mobilizing−for therapeutic purposes−the cultural and spiritual resources that already exist in that community. And the important point here is that that need not be in lieu of standard Western psychiatric treatments but alongside them. That ethos, of “multiple discourses” [25] transcends the dichotomy that has all too often characterized the relationship between mainstream (Western) mental health services and traditional healing [54].

In so far as it has also described sources of referral, diagnoses, demographics (as well as other characteristics) of all patients seen during the clinic’s first 15 months of operations, this paper addresses a gap that has been identified in the extant literature on integrated mental health services in Canadian First Nation communities. In the future we hope to have clearer, bi-directional referral pathways between psychiatrist and traditional healers, because to date, the psychiatrist has not had clear referral pathways available to him to facilitate access to indigenous spiritual and cultural practices that some patients in the clinic have expressed interest in being able to access.

On the subject of physicians’ payment, psychiatrists engaging in service development and other non-clinical work are unlikely to be appropriately compensated where the billing structure is exclusively fee-for-service. Second, the MSP system of British Columbia does not recognize a traditional healer as a legitimate source of referral. The latter issue is a particular cause for concern not only because it speaks to non-parity between psychiatrist and traditional healer but because it precludes the bi-directional referral of patients between psychiatrist and traditional healer, something that is absolutely integral to the sort of collaborative undertaking that we envisage. In the light of the above, alternative methods of physician compensation are currently being explored.

There is also interest in exploring novel models of care delivery in which the psychiatrist and traditional healer see clients together. Doing that either in a healing circle−with multiple clients−or with one client, are all possibilities currently being explored. There is also an interest in developing a research agenda which is able to demonstrate the usefulness of the collaborative endeavors that we have been engaged in in a way that is sensitive to indigenous values.

The clinic has facilitated improved access for members of the Sts’ailes community to culturally appropriate mental health services, but alarmingly high rates of psychiatric morbidity are seen in Canada’s First Nations, as a rule. And that being the case there is a pressing need for greater access to mental health services more globally, across different communities. Access, rather than being based on a geographical lottery, as is the case currently, should be more uniform. For that reason that we endorse the call that some commentators [13] have made for a national Aboriginal mental health strategy in Canada. While such a strategy will need to incorporate many considerations (manpower, interdisciplinary working, financial infrastructure and so forth) we believe that a vital element in that strategy would be a commitment to describing and documenting successful collaborative service models-such as that which the mental wellness clinic at Sts’ailes represents-so that they can be disseminated to others engaged in similar undertakings. Emphasized in this paper has been the embeddedness of the wellness clinic within the unique cultural and historical context of Sts’ailes. A major challenge then, as we consider the issue of psychiatric morbidity across Canada’s First Nations is to develop services that, similarly, remain sensitive to geographical, cultural, and historical particularities.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Leilani Francis and Karen Hollywood for administrative assistance and data collection in relation to this project.

References

- Duff W (1952) The upper stalo Indians of the Fraser Valley, British Columbia. British Columbia Provincial Museum, Victoria, Canada.

- Muckle RJ (2007) The First Nations of British Columbia: An anthropological survey. UBC Press, Vancouver, Canada.

- Cole D, Chaikin I (1990) An iron hand upon the people: The law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast. Douglas McIntyre, Vancouver, Canada.

- Barnett HG (1955) The coast salish of British Columbia. The University Press, Eugene.

- Jilek W (1981) Indian healing: Shamanic ceremonialism in the Pacific Northwest today. Hancock House, Surrey, British Columbia.

- Jilek WG (1974) Indian healing power-indigenous therapeutic practices in the pacific northwest today. Psychiatric Annals 11: 13-21

- Jilek WG (1976) Brainwashing as therapeutic technique in contemporary canadian indian spirit dancing - a case in theory building. Anthropology and Mental Health, The Hague, Mouton, pp: 63-75.

- Jilek W (1978) Native renaissance: The survival and revival of indigenous therapeutic ceremonials among North American Indians. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review. 15: 117-147

- Jilek W, Jilek-Aall L (1978) The psychiatrist and his shaman colleague: Cross-cultural collaboration with traditional Amerindian therapists. J Operational Psychiatry 9: 32-39.

- Jilek W, Todd N (1974) Witchdoctors succeed where doctors fail: Psychotherapy among Coast Salish Indians. Can Psychiatr Assoc J. 19: 351-356.

- Smylie J, Firestone F, Cochran L, Prince C, Maracle S, et al. (2011) Our health counts. urban Aboriginal health database research project. Community Report: First Nations Adults and Children.

- Poonwassie A, Charter A (2005) Aboriginal worldview of healing: Inclusion, blending, and bridging. Thousand Oaks, Sage, USA, pp: 15-25.

- Maar MA, Erskine B, McGregor L, Larose TL, Sutherland ME, et al. (2009) Innovations on a shoestring: A study of a collaborative community-based Aboriginal mental health service model in rural Canada. Int J Mental Health Systems 3: 27.

- Benning TB (2016) Should psychiatrists resurrect the body? Adv Mind Body Med 30: 32-38.

- Jilek-All L (1976) The Western psychiatrist and his non-Western clientele. Can Psychiatr Assoc J 21: 353.

- Jenness D (1955) The faith of a Coast Salish Indian. Anthropology in British Columbia Memoirs No. 3. British Columbia Provincial Museum.

- Okello ES, Ekblad S (2006) Lay concepts of depression among the Baganda of Uganda: A pilot study. Transcult Psychiatry 43: 287-313.

- Gone JP (2008) “So I can be like a Whiteman”: The cultural psychology of space and place in American Indian mental health. Culture and Psychology 14: 369-399.

- Hatala A (2008) Spirituality and aboriginal mental health: An examination of the relationship between Aboriginal spirituality and mental health. Adv Mind Body Med 23: 6-12.

- Auger MD (2016) Cultural continuity as a determinant of indigenous peoples’ health: A metasynthesis of qualitative research in Canada and the United States. Int Indigenous Policy J 7: 4.

- Chandler MJ, Lalonde C (1998) Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s first nations. Transcultural Psychiatry 35: 191-219

- Gone J (2009) Encountering professional psychology: Valaskakis healing traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. UBC Press, Canada.

- Brascoupé S, Waters C (2009) Cultural safety: Exploring the applicability of the concept of cultural safety to Aboriginal health and community wellness. J Aboriginal Health 5: 6-41.

- Health Partnership Accord (2011) Joint publication of the First Nations Health Council, the British Columbia ministry for Health and Health Canada.

- Bakula B, Anderson FP (2013) Sts’ailes primary care project: Report.

- Gone J (2013) Redressing First Nations historical trauma: Theorizing mechanisms for indigenous culture as mental health treatment. Transcult Psychiatry 50: 683-706.

- Duran E (2006) Healing the soul wound: Counselling with American Indians and other Native Peoples. Teachers College Press, New York, USA.

- Kowpak D, Gillis l (2015) Aboriginal healthcare in Canada: The role of alternative service delivery in transforming the provision of mental health services. Dalhousie J Interdisciplinary Manag.

- Marsh TN, Coholic D, Cote-Meek S, Najavits LM (2015) Blending Aboriginal and Western healing methods to treat intergenerational trauma with substance use disorder in Aboriginal peoples who live in Northeastern Ontario, Canada. Harm Reduction J 12: 14.

- Nabigon HC, Wenger-Nabigon A (2012) “Wise Practices”: Integrating traditional teachings with mainstream treatment approaches. Native Social Work J 8: 43-55.

- Rojas M, Stubley T (2014) Integrating mainstream mental health approaches and traditional Aboriginal healing practices: A literature review. Adv Social Sciences Res J 1: 22-43.

- Benning TB (2016) Envisioning deep collaboration between psychiatry and traditional ways of knowing on a British Columbia First Nation. Fourth World J 15: 55-64.

- Iwama M, Marshall M, Marshall A, Bartlett C (2009) Two-eyed seeing and the language of healing in community-based research. Canadian J Native Educ 32: 3-23.

- Adelson (2009) Towards a recuperation of souls and bodies: Community healing and the complex interplay of faith and history. UBC Press Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Wieman C (2000) An overview of six nations mental health services In the mental health of indigenous peoples-proceedings of the advanced study institute McGill summer program in social and cultural psychiatry and the Aboriginal mental health research team pp: 29-31.

- Wieman C (2009) Six Nations Mental Health Services: A Model of Care for Aboriginal Communities. Healing Traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. UBC Press, Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Maar MA, Shawande M (2010) Traditional Anishinabe healing in a clinical setting: The development of an Aboriginal interdisciplinary approach to community –based Aboriginal mental health care. J Aboriginal Health 6: 18-27.

- Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada (2010) Indigenous Western and traditional doctors forum final report, September 2009.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th edn.) Washington DC, USA.

- Overmars D (2010) Diagnosis as a naming ceremony: Caution warranted in use of the DSM-IV with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. First Peoples Child & Family Review 5: 78-85.

- de Jong JTVM (2005) Analysing critique on PTSD in an attempt to bridge anthropology and psychiatry. Medicsche Antropologie 17: 1

- Marsella AJ (2010) Ethnocultural aspects of PTSD: An Overview of concepts, issues, and treatments. Traumatology 16: 17-26.

- Brave MYH (1999) Gender differences in the historical trauma response among the Lakota. J Health Soc Policy 10: 1-21.

- Brave MYH, De Bruyn L (1998) The American holocaust: Historical unresolved grief. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 8: 56-78.

- Sotero M (2006) A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. J Health Disparities Research and Practice 1: 93-108.

- Torrey FE (1986) Witchdoctors and psychiatrists: The common roots of psychotherapy and its future. Harper & Row, New York, USA.

- Bradley L (2011) Narrative psychiatry: How stories can shape clinical practice. Johns Hopkins Press, New York, USA.

- Charon R (2006) Narrative medicine: Honoring the stories of illness. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Mehl-Madrona L (2007) Narrative medicine: The use of history and story in the healing process. Bear & Company Rochester, USA.

- Cajete G (2000) Native science: Native laws of interdependence. Clear Light Publishers, Santa Fe, USA.

- First Nations and Inuit Health (1998) National native alcohol and drug abuse program: General review.

- First Nations and Inuit Health (2003) A statistical profile on the health of First Nations in Canada: Determinants of Health, 2006 to 2010. Health Canada.

- Hatala A (2012) The status of the “biopsychosocial model” in health psychology: Towards an integrated approach and a critique of cultural conceptions. Open J Med Psychol 1: 51-62.

- Ruiz P, Langrod J (1976) Psychiatry and folk healing: A dichotomy? Am J Psychiatry 133: 95-97.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4536

- [From(publication date):

June-2017 - Apr 16, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 3700

- PDF downloads : 836