Mini Review Open Access

Structures and Biosynthesis of Enediyne Natural Products

Rui Ji1#, Fuli Liu2#, Lingbin Meng3 and Xiaolei Chen4*1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular biology, University of Louisville, School of Medicine, Louisville, KY 40202, USA

2Department of Physiology and Neurobiology, Geisel Medical School at Dartmouth, Lebanon, NH 03756, USA

3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular biology, University of Louisville, School of Medicine, Louisville, KY 40202, USA

4Department of Chemistry, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755, USA

#The first two authors contributed equally

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Xiaolei Chen

Department of Chemistry

Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755, USA

E-mail: xiaolei.chen@dartmouth.edu

Received date: June 12, 2014; Accepted date: June 25, 2014; Published date: July 02, 2014

Citation: Rui J, Fuli L, Lingbin M, Xiaolei C (2014) Structures and Biosynthesis of Enediyne Natural Products. Int J Adv Innovat Thoughts Ideas 3:157. doi:

Copyright: © 2014 Rui Ji, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and production in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Advance Innovations, Thoughts & Ideas

Abstract

Enediyne natural products are important member of natural product family with strong DNA cleavage activity. This biological activity makes them excellent candidates for developing novel antibiotics and antitumor drugs. Highly unsaturated enediyne cores, sugar moieties and aromatic moieties are basic components of structures of enediyne natural products. Genes encoding enzymes responsible for enediyne natural product biosynthesis are clustered in enediyne gene clusters. Each gene cluster consists of dozens of genes that encode enzymes for biosynthesis of enediyne core, sugar moieties and aromatic moieties as well as tailing enzymes.

Review

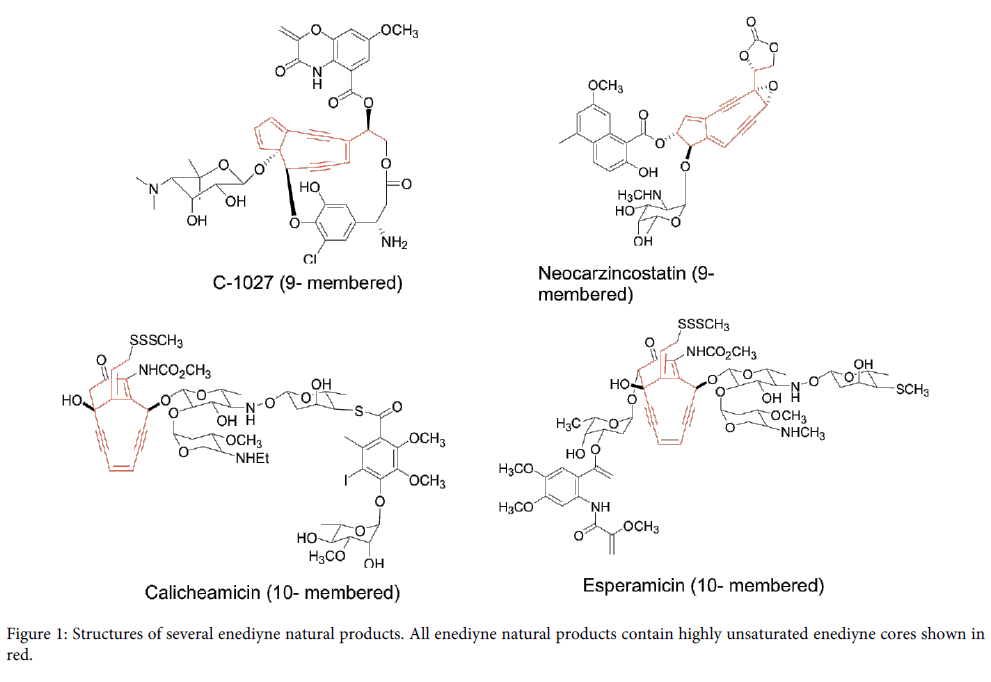

Natural products produced by many plants, bacteria and fungi as secondary metabolites have been the major drug source for pharmaceutical industry for the last several decades [1]. Enediyne natural products discovered in 1980s are unique member among natural product family with potent DNA cleavage activity [2-4]. A typical enediyne natural product is structurally characterized by a highly unsaturated enediyne core containing two acetylenic groups conjugated to a double bond in nine- or ten- membered carbocycle [5]. Thus the enediyne natural products are conveniently categorized into two subfamilies, nine-membered enediynes and ten-membered enediynes. Figure 1 shows several examples of nine-membered enediynes (C-1027 from Streptomyces globisporus [6] and neocarzinostatin fromStreptomyces macromomyceticus [7]) and ten-membered enediynes (calicheamicin from Micromonospora echinospora [8] and esperamicin from Actinomadura verrucosopora [9].

Figure 1: Structures of several enediyne natural products. All enediyne natural products contain highly unsaturated enediyne cores shown in red.

Although total synthesis of almost all enediyne natural products has been achieved by organic synthesis [10-13], the blue print of their biosynthesis in cells is still not quite clear to us. Before discovery and sequencing of enediyne gene clusters, researchers speculated biosynthesis pathways of enediyne natural products by biomimetic synthesis [14] and feeding of isotope labeled starting material to enediyne producing bacteria strains [15].

Discovery and sequencing of gene clusters for C-1027 and calichaemicin biosynthesis announced the genomic era of enediyne biosynthesis study [16-18]. Sequencing of gene clusters for neocarzinostatin, naduropeptin and dynemicin [19-22] quickly followed the above two pioneer reports. All enediyne gene clusters encode a conserved iterative enediyne type I polyketide synthase (PKSE). Although we are convinced that the role of PKSE is to provide a carbon skeleton for synthesis of enediyne cores, the genuine structure of the carbon skeleton is not confirmed and whether 9-membered and 10-membered enediyne cores share the same intermediate carbon skeleton is still under debate. Several polyketide products were isolated from expression of 9-membered PKSE SgcE and 10-membered PKSE CalE8 in E. coli and also from in vitro assays of their activities. The isolated polyketides include heptaene [23], methylhexaenone [24] and nonaketide [25], and other truncated polyketides [26-29]. These polyketides are potential precursors towards enediyne core biosynthesis, as claimed by their discoverers. However, some people argue that none of these polyketides is true precursor and PKSE needs a trans-acting enzyme for function regulation [26,27,30,31]. Moreover, what enzymes are involved in maturation of the carbon skeletons to enediyne cores is still a mystery to us.

While the enediyne cores serve as active sites of DNA cleavage activity, peripheral moieties such as sugar moieties and aromatic moieties are responsible for DNA binding specificity and stabilization of enediyne cores. Structures of enediyne cores are rather conserved among enediyne natural products, and diversity of enediyne natural product family is achieved by variations of peripheral moieties. As a result, biosynthesis pathways for peripheral moieties are less conserved among enediynes. Due to limit of space, detailed discussion on various biosynthesis pathways of enediyne peripheral moieties is not provided in this paper. Interested readers are encouraged to read reports on biosynthesis of C-1027 [17] and calichaemicin [16] and Liang’s review paper [32].

In summary, enediyne natural possess exquisite structures and valuable biological activities. Biosynthesis of enediynes is a complicate and highly regulated process involving 70~80 gene products from enediyne gene clusters. Synthesis of enediyne cores starts with function of iterative type I polyketide synthases, whose role is yet to be established by further research. Synthesis of peripheral sugar and aromatic moieties are much more diverse among enediynes. Most enzymes responsible for synthesis of these moieties and covalent attachment to enediyne cores have already been assigned with related functions.

References

- Newman DJ, Cragg (2007) Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod.70: 461-477.

- Staunton J, Weissman KJ (2001) Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat Prod Rep 18: 380-416.

- Walsh CT (2004) Polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: Modularity and versatility. Science 303: 1805-1810.

- Zazopoulos E, Huang K, Staffa A, Liu W, Bachmann BO, et al. (2003) A genomics-guided approach for discovering and expressing cryptic metabolic pathways. Nat Biotechnol 21: 187-190.

- Smith AL, Nicolaou KC (1996) Theenediyne antibiotics. J Med Chem 39: 2103-2117.

- Hu, J., et al., A New Macromolecular Antitumor Antibiotic, C-1027 .1. Discovery, Taxonomy of Producing Organism, Fermentation and Biological-Activity.Journal of Antibiotics, 1988. 41(11): p. 1575-1579.

- Edo, K., et al., The Structure of NeocarzinostatinChromophore Possessing a Novel Bicyclo-[7,3,0]Dodecadiyne System. Tetrahedron Letters, 1985. 26(3): p. 331-334.

- Maiese WM, Lechevalier MP, Lechevalier HA, Korshalla J, Kuck N, et al. (1989) Calicheamicins, a Novel Family of Antitumor Antibiotics - Taxonomy, Fermentation and Biological Properties. J Antibiot 42: 558-563.

- Konishi M., et al., Esperamicins, a Novel Class of Potent Antitumor Antibiotics .1. Physicochemical Data and Partial Structure.Journal of Antibiotics, 1985. 38(11): p. 1605-1609.

- Nicolaou, K.C., et al., Total Synthesis of Calicheamicin Gamma-1(I). Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1992. 114(25): p. 10082-10084.

- Nicolaou KC, Chen JS, Zhang H, Montero A, et al. (2008) Asymmetric synthesis and biological properties of uncialamycin and 26-epi-uncialamycin. AngewChemInt Ed Engl 47: 185-189.

- Ren F, Hogan PC, Anderson AJ, Myers AG (2007) Kedarcidinchromophore: Synthesis of its proposed structure and evidence for a stereochemical revision. J Am ChemSoc 129: 5381-5383.

- Ji, R., Tyro-3, Axl, and Mertk (TAM) Receptors Maintain Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. 2012: University of Louisville.

- Schreiber SL, Kiessling LL (1988) Synthesis of the Bicyclic Core of the EsperamicinCalichemicin Class of Antitumor Agents. J Am ChemSoc 110: 631-633.

- Hensens OD, Giner JL, Goldberg IH (1989) Biosynthesis of NcsChrom-a, the Chromophore of the Antitumor Antibiotic Neocarzinostatin. J Am ChemSoc 111: 3295-3299.

- Ahlert J, Shepard E, Lomovskaya N, Zazopoulos E, Staffa A, et al. (2002) The calicheamicin gene cluster and its iterative type I enediyne PKS. Science 297: 1173-1176.

- Liu W, Christenson SD, Standage S, Shen B (2013) Biosynthesis of the enediyne antitumor antibiotic C-1027. Science 297: 1170-1173.

- Balmer, J., et al., Presence of the Gpr179nob5 allele in a C3H-derived transgenic mouse. Molecular vision, 2013. 19: p. 2615.

- Gao Q, Thorson JS (2008) The biosynthetic genes encoding for the production of the dynemicinenediyne core in Micromonosporachersina ATCC53710. FEMS MicrobiolLett 282: 105-114.

- Liu W, Nonaka K, Nie L, Zhang J, Christenson SD, et al. (2005) The neocarzinostatin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces carzinostaticus ATCC 15944 involving two iterative type I polyketide synthases. ChemBiol 12: 293-302.

- Van Lanen SG, Oh TJ, Liu W, Wendt-Pienkowski E, Shen B (2007) Characterization of the maduropeptin biosynthetic gene cluster from Actinomaduramadurae ATCC 39144 supporting a unifying paradigm for enediyne biosynthesis. J Am ChemSoc 129: 13082-13094.

- Yan XB, Wang SS, Hou HL, Ji R, Zhou JN (2007) Lithium improves the behavioral disorder in rats subjected to transient global cerebral ischemia. Behav Brain Res 177: 282-289.

- Zhang J, Van Lanen SG, Ju J, Liu W, Dorrestein PC, et al. (2008) A phosphopantetheinylatingpolyketide synthase producing a linear polyene to initiate enediyne antitumor antibiotic biosynthesis. ProcNatlAcadSci U S A 105: 1460-1465.

- Kong R, Goh LP, Liew CW, Ho QS, Murugan E, et al. Characterization of a carbonyl-conjugated polyene precursor in 10-membered enediyne biosynthesis. J Am ChemSoc 130: 8142-8143.

- Chen X, Guo ZF, Lai PM, Sze KH, Guo Z (2010) Identification of a Nonaketide Product for the Iterative Polyketide Synthase in Biosynthesis of the Nine-Membered Enediyne C-1027. AngewandteChemie-International Edition 49: 7926-7928.

- Belecki K, Crawford JM, Townsend CA (2009) Production of OctaketidePolyenes by the CalicheamicinPolyketide Synthase CalE8: Implications for the Biosynthesis of Enediyne Core Structures. J Am ChemSoc 131(35): 12564-12564.

- Sun H, Kong R, Zhu D, Lu M, Ji Q, et al. (2009) Products of the iterative polyketide synthases in 9-and 10-membered enediyne biosynthesis. ChemCommun, 2009: 7399-7401.

- Ji R, Tian S, Lu HJ, Lu Q, Zheng Y, et al. (2013) TAM Receptors Affect Adult Brain Neurogenesis by Negative Regulation of Microglial Cell Activation. J Immunol 191: 6165-6177.

- Jiang M, Chen X, Wu XH, Chen M, Wu YD, et al., Catalytic Mechanism of SHCHC Synthase in the Menaquinone Biosynthesis of Escherichia coli: Identification and Mutational Analysis of the Active Site Residues. Biochemistry, 2009. 48(29): p. 6921-6931.

- Halo LM, Marshall JW, Yakasai AA, Song Z, Butts CP et al. (2008) Authentic heterologous expression of the tenellin iterative polyketide synthase nonribosomal peptide synthetase requires coexpression with an enoyl reductase. Chembiochem 9: 585-594.

- Chen M, Ma X, Chen X, Jiang M, Song H, et al. (2013) Identification of a Hotdog Fold Thioesterase Involved in the Biosynthesis of Menaquinone in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 195: 2768-2775.

- Liang, ZX (2010) Complexity and simplicity in the biosynthesis of enediyne natural products. Nat Prod Rep 27: 499-528.

Relevant Topics

- Advance Techniques in cancer treatments

- Advanced Techniques in Rehabilitation

- Artificial Intelligence

- Blockchain Technology

- Diabetes care

- Digital Transformation

- Innovations & Tends in Pharma

- Innovations in Diagnosis & Treatment

- Innovations in Immunology

- Innovations in Neuroscience

- Innovations in ophthalmology

- Life Science and Brain research

- Machine Learning

- New inventions & Patents

- Quantum Computing

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 20991

- [From(publication date):

November-2014 - Jul 05, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 16220

- PDF downloads : 4771