Stillbirth in a University Maternity of Porto-Novo, in Southern Benin: Epidemiological and Etiological Aspects

Received: 30-Aug-2017 / Accepted Date: 13-Oct-2017 / Published Date: 20-Oct-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000353

Abstract

Summary: Stillbirth remains largely unknown in our developing countries, where many fetal deaths are not systematically recorded. Efforts still need to be made to understand the causes of stillbirth in Benin. Objective: To study the epidemiological and etiological aspects of stillbirth. Framework and study method: This is a retrospective descriptive study on 1,010 stillbirths collected at the University Maternity of Porto Novo in Benin from January 1, 2013 to June 30, 2016. Results: During the study period, we recorded 1,010 stillbirths out of 13,069 births. The overall stillbirth rate is 83.8%. The highest proportions of stillbirths were among women with the following characteristics: Age between 20 and 34 (80.2%), retailers/traders (55.8%), married women (87, 1%), referred from peripheral health facilities (82%), paucigest (33.5%), pauciparous (33.8%), multiparous (31.7%) and the large multiparity group (14.2%). Etiologies are haemorrhages (38.8%), infections (17.6%), vascular renal syndromes (16.4%), unknown causes (11.8%), obstructed labor (dystocia) (9.8%), Cord diseases (5.9%), fetal abnormalities (1.6%), non-infectious maternal pathologies (0.9%) and other causes (2.1%). Conclusion: Reducing stillbirth involves improving the health system and strengthening health infrastructures. Supervision of women with high-risk pregnancies, screening and management of diseases during pregnancy are necessary in order to reduce the frequency of fetal death in utero in our environment.

Keywords: Stillbirth; Frequency; Epidemiological characteristics; Etiologies

Introduction

Stillbirth remains largely unknown in our developing countries where many fetal deaths are not systematically recorded in the statistics. According to a review published in 2011 in Lancet, millions of stillbirths unaccounted for and not reflected in global policies, such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), occur each year [1]. Such a silence would hide the seriousness of the problem and prevent investigations. According to the same report, the rate of reduction in the global number of stillbirths fell slightly by 1% per year from 1995 to 2009, in contrast to the progress made in reducing maternal and infant mortality. Efforts still need to be made to understand the etiologies of stillbirths with a rate of 25% in Benin [2].

Materials and Study Method

This is a descriptive retrospective study carried out from January 1, 2013 to June 30, 2016, at the University maternity hospital of Porto Novo in Benin. It covered all deliveries recorded within the maternity during our study period. All cases of deaths in utero or intrapartum deaths recorded in the service during the study period, with a gestational age ≥ 28 weeks or a birth weight ≥ 1000 g were also included. Deaths born outside the maternity, newborns with apparent death (suspended animation) (Apgar score=3), cases of expulsion of products of conception before the 28th week and deaths of early neonatal period were not taken into account.

Sampling is systematic with full recruitment of all cases meeting our inclusion criteria. Variables studied are the dependent variables (stillbirths) and the independent variables (socio-demographic profile of new mothers).

For data collection, we have used obstetric records, delivery registers, operating room registers and operating protocols for parturient women who delivered stillborn babies during the study period. The data were collected on a survey sheet prepared for this purpose.

Data processing was done using SPSS 20.0 and EPI Info version 7. For the analysis of data, the Chi-2 test has been used and the difference is statistically significant for a p ≤ 0.005.

Ethical aspects

The study has been carried out with the approval of administrative authorities at different levels. Confidentiality and anonymity of the data have been respected.

Results

Stillbirth rate

In the course of our study, we have selected 971 obstetric files that could be used. The number of stillbirths recorded is 1,010 out of a total of 13,069 births, giving a stillbirth rate of 83.8%.

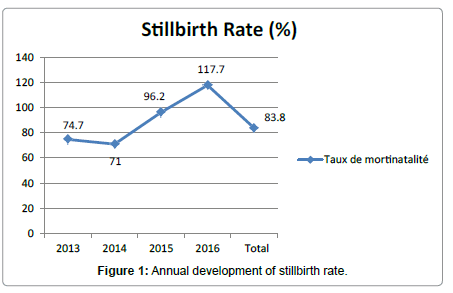

Figure 1 shows the annual distribution of stillbirth rate.

The lowest stillbirth rate has been noticed in 2014 at 71%.

Socio-demographic profile of women who have recently given birth

The distribution of stillbirths according to the socio-demographic profile of new mothers is given in Table 1.

| s | Number (N=1,010) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 535.2 | ||

| 20-34 years | 810 | 80.2 |

| ≥ 35 years | 147 | 14.6 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 670 | 66.3 |

| Rural | 340 | 33.7 |

| Occupation | ||

| Retailer/Tradeswoman | 564 | 55.8 |

| Craftswoman | 257 | 25.4 |

| Housekeeper/Farmer | 98 | 9.8 |

| Civil servant | 52 | 5.1 |

| Pupil/Student | 39 | 3.9 |

| Statute matrimonial | ||

| Married | 880 | 87.1 |

| Single | 130 | 12.9 |

Table 1: Distribution of stillbirths according to the socio-demographic profile of women who have recently given birth.

• The mean age of mothers who had given birth to stillborn babies is 27.90 ± 5.67 years with extremes of 15 and 45 years. It is observed that 80.2% of fetal deaths occur in women aged 20 to 34 years.

• About 66.3% of stillbirths occurred among mothers leaving in the urban area, 55.8% of mothers are retailers/traders and married women account for 87.2%.

Etiologies

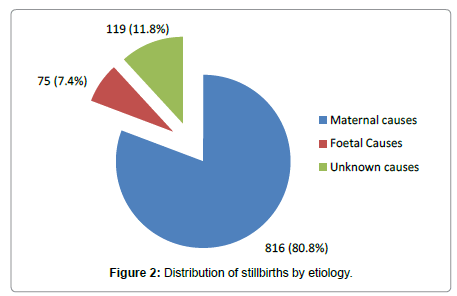

In our series, the causes of fetal deaths are known in 891 cases that’s 88.2%. These causes are sorted into three categories which are: Maternal, fetal and adnexal causes. No cause was identified in 119 cases or 11.8% (Figure 2). Maternal causes responsible for fetal death are dominated by vascular renal syndromes in 16.4%, malaria in 9% and uterine rupture in 5.8%.

Fetal and adnexal causes are grouped into Table 2.

| Causes | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal causes | ||

| Fetal Dystocia | 97 | 9.6 |

| Retention of the second twin | 30 | 3 |

| FPD | 28 | 2.8 |

| Neglected Shoulder Presentation | 12 | 1.2 |

| Shoulder dystocia | 6 | 0.6 |

| Retention of the after-coming head | 5 | 0.5 |

| Fetal Abnormality | 16 | 1.6 |

| Total | 194 | 19.3 |

| Adnexal causes | ||

| RPH | 244 | 24.2 |

| PP | 90 | 8.9 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 73 | 7.3 |

| Umbilical cord prolapse | 34 | 3.4 |

| Circular of umbilical cord/looping | 25 | 2.5 |

| Total | 466 | 46.3 |

*FPD: Fetopelvic Disproportion; RPH: Retro-Placental Hematoma .

Table 2: Distribution of stillbirths according to fetal and adnexal causes.

RPH and Placenta Previa (PP) are the dominant adnexal causes with respective frequencies of 24.2% and 8.9%.

Table 3 shows the distribution of stillbirths according to their causes and the period of fetal death.

| Causes of stillbirth | Antepartum n (%) |

Intrapartum n (%) |

Unknown n (%) |

Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetric haemorrhage | 202 (20) | 147 (14.5) | 43 (4.3) | 392 (38.8) |

| Infections | 157 (15.5) | 13 (1.3) | 7 (0.8) | 177 (17.5) |

| Vascular renal syndromes | 139 (13.8) | 21 (2.1) | 5 (0.5) | 165 (16.4) |

| Unknown causes | 102 (10.1) | 5 (0.5) | 12 (1.2) | 119 (11.8) |

| Dystocia | - | 98 (9.8) | - | 98 (9.8) |

| Cord diseases | 18 (1.8) | 39 (3.9) | 2 (0.2) | 59 (5.9) |

| Fetal Abnormalities | 15 (1.5) | 1 (0.1) | - | 16 (1.6) |

| Non-infectious maternal diseases | 9 (0.9) | - | - | 9 (0.9) |

| Other | 19 (1.9) | 2 (0.2) | - | 21 (2.1%) |

| Total | 661 (65.5) | 326 (32.4) | 69 (7) | (104.8) |

*Other: Trauma, post-term pregnancy/term exceedance.

Table 3: Distribution of stillbirths according to cause of stillbirth and period of death.

Several causes can be found simultaneously. Obstetric haemorrhage is the leading cause of fetal deaths with 38.8%.

Discussion

Frequency

In our study, the overall stillbirth rate was 83.8%. The lowest rate of 71% has been recorded in 2014. This rate varies from one country to another, but also from one region to another.

In the literature, the stillbirth rate in Africa is high, between 23 and 108% [3-5]. The high rate is explained by the low socio-economic level of the population, inadequate health development and difficulties in accessing health care.

However, a significant difference must be noted with the rates reported in developed countries [6,7]. These rather disparate results between developed and developing countries highlight all the effort that remains to be made in the prevention of stillbirths. Indeed, the improvement of the health system through the reinforcement of sanitary equipment, medical supervision of pregnancy and childbirth, would have made it possible to reduce the stillbirth rate in our countries.

Socio-demographic profile of women who have recently given birth

The mean age of mother with a stillbirth is 27.90 ± 5.67 years with extremes of 15 and 45 years. It is observed that 80.2% of stillbirths are registered among mothers aged between 20 and 34 years. Our results are stackable to those obtained by the Cheptum group in Kenya, who found a frequency of 80.3% [8]. This same trend is reported by Okeudo et al. in Nigeria with 81.5% of cases [9]. In contrast, Vaishali and Pradeep in India recorded a lower frequency of 59.1% [10]. However, in the literature, some authors agree on an increased risk of stillbirth in women over 35 years of age [11]. We believe that the strong representativeness of stillbirths of mothers aged 20 to 34 in our series can be explained by the fact that this age group represents the period in the life of the woman where the reproductive activity is the most important. With regard to marital status, stillbirth can affect both a single woman and a married woman [11,12]. We also believe that marital status does not directly interfere with the occurrence of death in utero.

Women who have experienced stillbirths are mostly retailers because this is the main activity of people in southern Benin. Moreover, in this socio-professional layer, low-income illiterates, with little respect for prenatal care and subject to physical exhaustion predominate. All of these factors could lead to morbid conditions that cause fetal death.

Etiologies are dominated by:

Obstetric hemorrhage: Sudden and unpredictable, obstetric haemorrhages require rapid and well-organized management. In our series, they were the first etiology of stillbirths with a frequency of 38.8% and were more frequent before delivery (20%).

Many studies of uterine ruptures report these morbid and fatal consequences for both the mother and the fetus [13,14]. They are the consequence of unknown or neglected dystocia, untimely manipulations on scarred uterus or the improper use of oxytocin. The very high mortality observed in our study was mainly due to the brutality of the appearance of obstetric haemorrhages, the severity of the clinical picture, as well as their rapid evolution and the delay in their management.

Infection: Infectious pathologies appear to be frequent etiologies of stillbirths. Their rate varies greatly according to the population studied. In the literature, Ntuli and Malangu [15] and in South Africa found 1% of cases and Andriamandimbison [16] in Madagascar, 11.6%.

In our series, they represent 17.6% of the causes of stillbirths, including 9% of malaria and 7.3% of ovular infections. Botolahy et al. in Madagascar established the protective role of at least one dose of Sulfadoxine Pyrimethamine and the use of insecticide-treated nets in the malaria prevention in pregnant women [17]. We believe that these high rates in our series are due to the geographical location of our country (highly endemic area) and to the lack of anti-malarial prophylaxis during prenatal consultations.

The amniotic infection complicating premature rupture of the membranes in our study accounts for 7.3% of the causes of late fetal death compared with 5.8% in Andriamandimbison et al. [16]. Zeraïdi et al., in their study in Morocco on 480 cases of premature rupture of the membranes, found 19.6% of amniotic infection cases. Death occurred before labor in 1% of cases, during labor in 1.7% of fetuses [18]. We can explain that premature rupture of the membranes is most often associated with prematurity and ovular infection on which depends the mother-to-child prognosis, as well as the quality of the management.

In our developing countries, infections continue to exact a heavy toll on fetus. This is due to the failure to diagnose the germ involved in most cases, which justifies the use of rather probabilistic therapeutics. Indeed, the totality of our patients had not made an infectious assessment because of lack of financial means

Vascular renal syndromes: They constitute the third cause of fetal deaths in 16.4% of the cases of our series. In some studies, they are strongly related to fetal death [19]. In Parakou in Benin, Tchaou et al. reported that hypertension pathologies accounted for 16.4% of obstetric emergencies [20]. These different studies allow us to say that high blood pressure remains a frequent cause of stillbirth. This high rate may be due to poor monitoring of high risk pregnancies and management of pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Unknown causes: Randrianarivo finds 8% of the causes of stillbirth [14]. In our study, we recorded 11.8% of fetal deaths whose causes could not be determined. Higher rates are reported in the works of Vaishali and Andriamandimbison, that’s 18.8% and 18.3% [16]. Ntuli and Malangu [15] recorded a frequency three times greater than ours in 40% of cases.

In the literature, 11% of stillbirths remain unknown [4]. This shows that etiological research may sometimes be unsuccessful, regardless of the means and the technical platform available. The high proportions of unknown causes in our studies show that means available to us for etiological research are limited. This is due, on the one hand, to the high costs of certain assessments (biopsy, karyotype) which are not accessible to all and on the other hand, to the cultural considerations of stillbirth (divine will, witchcraft)

Dystocia: Labour Dystocia causing fetal death is the result of poor delivery monitoring. They are, in fact, precursors of fetal distress that can aggravate the fetal prognosis in the lack of adequate management.

In the literature, several authors have emphasized the feticide role of obstetric dystocia during childbirth [6]. In our series, dystocia accounted for 9.8% of stillbirth etiology. Moreover, European studies on stillbirths nowhere refer to dystocia among the causes of stillbirths because they are no longer causes of stillbirth in developed countries [6]. The high rate in our resource-challenged countries may be related to the inadequacy of the technical platform available to us for the research of risk factors during pregnancy

Funicular pathologies: Funicular pathologies such as compression of umbilical cord and its vessels lead to serious accidents in the fetus. In our study, the frequency of late fetal deaths related to cord pathologies is 5.9%. Its lower compared to that reported by Ntuli and Malangu, 13% [15] and Andriamandimbison et al., 9.2% [16]. As far as the umbilical cord prolapse is concerned, we comply with authors who agree on their responsibility in the occurrence of fetal death.

Fetal abnormalities: They represent 1.6% of fetal deaths. In high techcountries, the proportion of fetal abnormalities that cause fetal death is high compared to our African countries. In some developing countries such as ours, ultrasound is not available everywhere and is often performed by low-skilled staff while it’s important in prenatal diagnosis of abnormalities.

Maternal non-infectious diseases: These represent 9% of the etiologies of fetal deaths in our series and are almost entirely intrapartum. They include diabetes (0.4%), sickle-cell anemia (0.3%) and fetal-maternal blood group incompatibilities (0.2%). Stillbirth is a serious complication of pregnancy in women whose diabetes is poorly known or unbalanced. It was responsible for 3% of fetal deaths in Ntuli and Malangu [15] and 9.4% in Andriamandimbison et al. [16]. We find that fetal prognosis depends on gestational age and the quality of diabetes supervision during pregnancy.

Pregnancy in sickle cell patients: It is a high-risk pregnancy both for the mother and the fetus. Leborgne et al. found 15% of death in utero related to sickle cell anemia in a study carried out in Guadeloupe in 2000 [21]. This frequency is doubly higher than that recorded in our series (0.3%), knowing that not all women were able to carry out the hemoglobin electrophoresis in their antenatal assessment.

The systematic identification of the mother’s blood group and the Rhesus factor during pregnancy and the administration of anti-D immunoglobulin have decreased the incidence of Rh alloimmunization in our hospitals. But despite all these preventive measures, the mortality related to this accident is topical. It was 0.2% in our study. The absence of systematic screening of maternal non-infectious diseases during pregnancy due to the high costs of prenatal assessment makes it impossible to estimate their incidence accurately.

Conclusion

Stillbirth is a real public health problem, especially in Africa. Haemorrhages, infections and hypertension pathologies are the first three identified causes of stillbirth in our study. Certain etiologies are accessible to prevention through improving the quality of obstetric care and the conditions of childbirth. The downward trend in the stillbirth rate depends on improving the health system and strengthening health infrastructures.

References

- Cousens S, Blencowe H, Stanton C, Chou D, Ahmed S, et al. (2011) National, regional and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2009 with trends since 1995: A systematic analysis. Lancet 377: 1319-1330.

- Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Économique (INSAE) (2012) Enquête démographique et de santé.

- Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, Amouzou A, Mathers C, et al. (2016) Stillbirths: Rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet 387: 587-603.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2012) Born too soon: The global action report on preterm birth.

- Diallo F, Baldé I, Diallo B, Diallo A, Baldé O, et al. (2016) Mortinatalité: Aspects socio-démographiques à l’hôpital régional de kindia en guinée. Revue De Médecine Périnatale 8: 103-107.

- WHO, World Bank Group and United Nations Population Division (2015) Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015.

- Chalumeau M (2002) Identification des facteurs de risque de mortalité périnatale en Afrique de l’Ouest: consultation prénatale ou surveillance de l’accouchement? J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 31: 63-69.

- Cheptum J, Muiruri N, Mutua E, Gitonga M, Juma M (2016) Correlates of stillbirthat Nyeri Provincial General Hospital, Kenya, 2009-2013: A retrospective study. Int J MCH AIDS 5: 24-31.

- Okeudo C, Ezem B, Ojiyi E (2012) Stillbirth rate in a teaching hospital in South-Eastern Nigéria: A silent tragedy. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2: 176-179.

- Vaishali N, Pradeep RG (2008) Causes of stillbirth. J Obstet Gynecol India 58: 314-318.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2002) ACOG practice bulletin: No 24, Feb 2001, management of recurrent pregnancy loss. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 78: 179-190.

- Engmann C, Walega P, Aborigo R, Adongo P (2012) Stillbirths and early neonatal mortality in rural Northern Ghana. Trop Med Int Health 17: 272-282.

- Ministère de la Santé du Bénin (2013) Annuaire des statistiques sanitaires 2013.

- Randrianarivo H (2006) Etude des 178 MFIU dans le sud de l’île de la réunion en 2001-2004. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 35: 665-672.

- Ntuli ST, Malangu N (2012) An investigation of the stillbirths at a tertiary hospital in limpopo province of South Africa. Glob J Health Sci 4: 141-147.

- Andriamandimbison Z, Randriambololona DMA, Rasoanandrianina B, Hery R (2013) Etiologies de la mort fœtale in utero: A propos de 225 cas à l’hôpital Befelatanana. Médecine et santé Tropicales 23: 82-86.

- Botolahy Z, Randriambelomanana J, Imbara E, Rakotoarisoa H, Andrianampanalinarivo H (2011) Aspects du paludisme à Plasmodium falciparum pendant la grossesse selon les cas observés au Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Toamasina Madagascar. Rev Anest Réa Méd Urg 3: 23-26.

- Zeraïdi N, Alami H, Daha A, Rhrab B, Kharbache A, et al. (2004) Rupture prématurée des membranes: Aspects épidémiologiques, thérapeutiques et évolutifs de 480 cas. Maroc Médical Septembre 26: 171-174.

- Bensalem S, Lakehal A, Roula D (2014) Le diabète gestationnel dans la commune de Constantine Algérie: Etude prospective. Médecine des Maladies Métaboliques 8: 216-220.

- Tchaou B, Noukponou F, Zoumenou E, Chobli M (2015) Les urgences obstétricales à l’hôpital Universitaire de Parakou au Bénin: Aspects cliniques, thérapeutiques et évolutifs. Euro Sci J 11: 1857-7881.

- Leborgne Y, Janky E, Venditelli F, Salin J, Daijardin J-B, et al. (2000) Drépanocytose et grossesse: Revue de 68 observations en Guadeloupe. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 29: 86-93.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5739

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Oct 23, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4757

- PDF downloads: 982