STI Care Seeking Behavior and Associated Factors among Female Sex Working in Licensed Drinking Establishments' of Adama Town Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia 2017, by Employing Health Belief Model

Received: 23-Feb-2019 / Accepted Date: 21-May-2019 / Published Date: 28-May-2019

Abstract

Background: Female sex workers constitute one of the high risk groups for STIs including HIV acquisition and transmission. In many societies Female sex workers face stigmatization, marginalization and discrimination, including in the health-care sector due to this fact great majority of female sex workers tend to self-diagnose and seek over-the-counter medication from pharmacies or use traditional home remedies for STIs treatment rather than visit health institution. Hence, assessing the factors that hinder or facilitate STIs care seeking behavior in this population group is imperative.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 01/2017 to 30/2017 among 423 female sex workers. Interviewer administered standardized tool that were pre-tested in Mojo town was used to collect data. Backward conditional multivariate logistic regression model was employed to identify factors associated with STIs care seeking behavior.

Result: Among the respondents 55.9% have utilized STIs care services. Three constructs of the health belief model namely perceive susceptibility (AOR=2.33, CI: 1.13, 4.80), perceive severity (AOR=3.25, CI: 1.65, 6.41) and cue to action (AOR=2.82, CI: 1.46, 5.43) were significantly associated with STIs care seeking behavior. Furthermore, knowledge of sexual transmitted infection (AOR=5.36, CI: 3.08, 9.34), having symptoms of sexual transmitted infection (AOR=3.95, CI: 2.18, 7.16), having non-paying sexual partner (AOR=1.95, CI: 1.09, 3.48) and duration of sex work (AOR=0.5, CI: 0.29, 0.86) were among the modifying variables that show significant association.

Conclusions: The results of this research reveals that 3 components of the HBM perceptions namely perceived susceptibility and perceived severity and cue to action were significantly associated with STIs care seeking behavior. Among the modifying variables having sexual transmitted infection symptoms, knowledge of sexual transmitted infection, duration of sex work and having non-paying sexual partners were found to be strong predictors of STIs care seeking behavior among the female sex workers.

Keywords: Female sex workers; Perceptions; STI care seeking behavior; Adama; Ethiopia

Background

Female sex workers have been recognized in Ethiopia since olden times, although there are no documented data as to when and where female sex workers first appeared in the country. Few sources link the beginnings of sex business with the movement of kings, nobles and warlords, the development of cities and the advancement of trading [1]. In Ethiopia, it is illegal to operate a brothel establishment or procure sex workers for commercial purpose, but the sale of sex by women is not prohibited by law [2].

During the 1970s, female sex workers working in drinking establishments (hotels, bars and restaurants) and waitresses were periodically examined for Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) and other communicable diseases at government health institution, as a monitoring of the ‘weekly Venereal Diseases (VD) Control Program’. Nevertheless, this periodic STI and CD examination service was discontinued in the 1980s following VD Control Program integration with general health services [3]. In 1996 Female sex workers were recognized as population at risk of HIV by Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. FHAPCO in its 2010 report on the implementation of the UN Declaration on Commitment on HIV/AIDS as a matter of these declaration, female sex workers’ access to HIV prevention, and care services has increased dramatically with a network of drop-in centers all over the country providing advice, condoms and income generating activities [4].

The number of women entering in sex business is increasing especially in the sub-Saharan African countries escalated by problems associated with urbanization, pressure from poverty, food and political insecurity and civil unrest. Female sex workers constitute one of the high risk groups for STIs and HIV/AIDS acquisition and transmission [5]. In many societies FSW face stigmatization, marginalization and discrimination, including in the health-care sector, which may delay treatment seeking [6]. Due to their high HIV prevalence, their increased ability to transmit HIV when co-infected with other STIs, and to the large population groups they reach through their sexual network, sex workers have long been targeted as the ‘core group’ most at risk of acquiring STI and HIV [7].

The continuing stigma and discrimination surrounding women who engage in sex work make the provision of comprehensive STI/HIV prevention, care, treatment and support for this vulnerable population challenging [8]. Only one third of FSWs in Sub-Saharan Africa had reported to receive adequate STI/HIV prevention interventions and very few number of female sex workers had access to STI/HIV prevention, treatment, care and support [9]. Female sex workers are venerable to a number of negative health consequences. They engage in high risk sexual behaviors, which might predispose them to sexually transmitted infections, rape, violence and adverse reproductive outcome. Despite these facts, they are in a poor position to utilize health service particularly sexual health care service when compared to the general population due to perception of health and illness, financial constraints and unfavorable conditions in the health care setup [10]. Furthermore, poor socio-economic conditions and working under hardship in order to financially support one’s family contributes to inadequate STI care service utilization among this group [11].

Female sex workers usually perceive themselves as inferior than other population and tend to lead their life in social isolation and this perceived disadvantaged position in the society has impacted the poor health care service utilization by the female sex workers [12]. Studies have evidenced that social and emotional factors inhibit female sex workers from utilizing STI care service [13]. There is a firm association between behavior to seek care timely and the perceived outcome of service utilization. The promptness of seeking care service will be due to the female sex workers own evaluation of their health, illness and risk behavior [14,15].

Due to delay in treatment seeking female sex workers suffer from the complications or late effects of STI infections, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (60% of cases of pelvic inflammatory diseases caused by an STI) the long-term sequelae include ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain and tubal infertility. The increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease-induced infertility is a health problem that is particularly important as female sex worker try to leave out of the sex work and change into other personal roles, such as trying to have a family [16]. Even though there is limited data on the incidence and prevalence of STIs in Ethiopia, the prevalence of STIs is generally believed to be high similar to that of other developing countries. Due to low level of knowledge regarding STI care service utilization large proportion of client seek care from traditional healers, pharmacy pharmacists, drug vendors shops and marketplaces, where the care is not the standard practice [17].

As to the investigators knowledge, this is the first study conducted among female sex workers on STI care seeking behavior. Previously published studies that applied HBM were conducted among groups other than female sex workers. The existing studies that have been undertaken in this group mainly assess HIV screening uptake, knowledge about STIs and condom utilization etc. So, this study addressed STI seeking behavior of female sex workers ’ and the predicting factors.

Methods

Study area and design

A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 01/2017 to 30/2017 in Adama town, Oromia National Regional State found at the distance of 99 km from Addis Ababa, based on the 2007 Census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, the city has a total population of 220,212, of whom 108,872 are men and 111,340 women. The town has a high concentration of bars, hotels, and night clubs where most female sex workers work. The majority of these facilities are located along the main Addis-Djibouti road, Adama- Asella road, and Kebele [15]. In the town, there are an estimated 6,000 female sex workers and 95 licensed drinking establishments [18,19]. Adama hosts several schools and colleges with a high number of youth. There are also some street girls and female school youth who practice commercial sex. Moreover, numerous industries and plantations attract many migrant workers from different part of the country.

Source population

All female sex workers working in licensed drinking establishments found in Adama town.

Study population

Female sex workers who were recruited from licensed drinking establishments and residing in Adama town by the time of the data collection process were considered to be the study population.

Sampling procedure and data collection

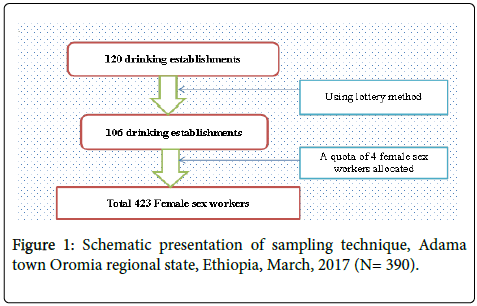

A quota sampling approach was employed to recruit the respondents. (As per WHO sampling hard to reach population recommendations and Ethiopian behavioral surveillance survey [20,21]. Preliminary exploration was undertaken to figure out the minimum number of female sex worker working in the drinking establishments for this list of all licensed drinking establishment was required to undergo the preliminary exploration and this registration list was obtained from Adama Town cultural and tourism office. The registration list contained information such as establishment’s address (kebeles and phone number), and types of the drinking establishments. Identification of the name of each establishment achieved by contacting and consulting with community health agent of each respective kebele offices and voluntary female sex workers working in FGAE confidential clinic. Based on the registration list the establishments where verified whether they are engaged in the business or not furthermore the minimum number of female sex workers working in each establishment was identified in the preliminary exploration. According to the preliminary exploration there were 120 drinking establishment in the town that are engaged in the business and the minimum number of female sex workers working in the establishments was found to be four. For the purpose of assigning equal “quota” to each drinking establishment the total sample size was divided by four which is the minimum number of female sex worker in the establishment and it gives 106 establishments. From the total of 120 establishments 14 establishments were excluded using lottery method. Finally, four female sex workers from each establishment were recruited in order to achieve the total sample size required. As shown in Figure 1. Ten voluntary female sex workers that have already been working with the FGAE confidential clinic were hired as data collectors.

Study variables and measurement

The outcome variable was STI care seeking behavior and respondents were asked if they had visited health facility for STIs concern (for treatment, receiving condom, screening, and consultation etc.) in the past 12 month. Independent variables were Age, educational status, duration of sex work, marital status, religion , past history of STIs symptoms, having non- paying client, type of paying client, use condom with non-paying client, use condom with paying client, age at first sexual intercourse, sexual behaviors, STIs knowledge, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits and perceived barriers. The health belief model constructs were measured by asking respondents a set of questions. The responses for these items ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The result was dichotomized in to two “High” and ‘Low” based on the mean score of the construct. Knowledge of STI was measured by asking respondents 8 question. The responses for the first items was 1 (“Yes”) 0 (“No”) and the rest 2 items asks to list STI symptoms in male and female. The correct response for yes no question had a score of one and if the respondent correctly mentions at least one symptoms of STI in female would have a score of 1 and if the respondent correctly mention at least one symptoms of STI in male would have a score of 1. Then scored points were dichotomized in to Good knowledge and poor knowledge depending on the mean score of knowledge of STI.

Data analysis

Data was checked for completeness, edited, cleaned, coded and entered in to Epi-Data version 3.1 and then exported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Univariate analysis was employed, first frequencies of each items was observed then the descriptive (measures of central tendencies and variations) was examined. Chi-square analysis was used to identify any significant association with STI care service utilization and selected variables. A final backward conditional multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify what factors best explain STI care seeking behavior. P-value of 0.05 or lower was taken to declare that the association is statistically significant. Strength of association of the variables was described using odds ratio at 95% confidence level. The result was presented as frequency table, graph and discussed with finding. Finally, possible recommendations were made based on the finding.

Ethical consideration

After approval of the proposal, ethical clearance and formal letter was obtained from Population and Family Health department and research ethics committee of Jimma University. Informed consent was obtained from each participant after explaining the purpose of the study. The anonymity of data was kept at all stage of data processing.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics

Among 423 female sex workers selected in the study, 390 were responded to the interviewer administered structured questionnaires making response rate of 92.2%. The mean age of the respondents was 24.05 with SD of 4.18. The minimum and the maximum age of respondents were 18 and 40 respectively. The overall sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are summarized by Table 1.

| No | Variables | Response | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | ≥24 | 226 | 57.9 |

| 25-34 | 157 | 40.3 | ||

| ≤35 | 7 | 1.8 | ||

| Total | 390 | 100 | ||

| 2 | Educational status | Unable to read and write | 52 | 13.3 |

| Read and write | 47 | 12.1 | ||

| Grade 1-8 | 158 | 47 | ||

| Grade 10-12 | 86 | 22.1 | ||

| Above grade 12 | 22 | 5.6 | ||

| Total | 390 | 100 | ||

| 3 | Marital status | Married | 58 | 14.9 |

| Single | 332 | 85.1 | ||

| Total | 390 | 100 | ||

| 4 | Religion | Orthodox Christian | 169 | 43.3 |

| Muslim | 101 | 25.9 | ||

| Protestant Christian | 73 | 18.7 | ||

| Catholic Christian | 45 | 11.5 | ||

| Other | 2 | 0.5 | ||

| Total | 390 | 100 | ||

| 5 | Any family to support | Yes | 185 | 47.4 |

| No | 205 | 52.6 | ||

| Total | 390 | 100 | ||

| 6 | Duration of sex work | 1-3 Years | 226 | 57.9 |

| >3 | 164 | 42.1 | ||

| Total | 390 | 100 |

Table 1: Socio demographic characteristics of female sex workers working in licensed drinking establishments of Adama town Oromia regional state, Ethiopia, March, 2017 (N=390).

Common STI symptoms in the past 12 month

Female sex workers were asked if they had history of common symptoms of STIs syndromes in the past 12 months, the majority 276 (70.8%) had history one or more of the symptoms of STIs. The common STIs symptom reported by the female sex workers in the past 12 month prior to the study is summarized by Table 2.

| No | Symptoms | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Genital discharge | 120 | 30.8 |

| 2 | Burning pain during urination | 78 | 20 |

| 3 | Genital ulcers/sore | 72 | 18.5 |

| 4 | Swellings In groin area | 60 | 15.4 |

*Multiple responses were possible; percentages calculated according to the female sex worker involved in each category and do not add up to 100 percent.

Table 2: Self-reported symptoms of STIs among female sex workers working in licensed drinking establishments of Adama town Oromia regional state, Ethiopia, March, 2017 (N=390).

Female sex workers’ STIs knowledge

Regarding Knowledge of STI, 367 (94.1%) of the respondents claimed to have ever heard about sexually transmitted infection (STIs) among them 179 (45.9%) of the respondent mentioned that STI can be prevented, 162 (45.9%) mentioned that STI can be cured and 139 (35.6%) mentioned that STI can be asymptomatic. One hundred sixty two (41.5%) of respondent correctly responded to the statement which inquires “people can protect them self’s by using condom correctly and consistently ” and 152 (39%) correctly responded to the statement which inquires “having one of STIs other than HIV can increase risk of acquisition of HIV”.

Female sex workers were also asked about the common sign and symptoms of STI both in women and men, 225 (57.7%) of the respondent mention at least one sign and symptom of STI in women the common mentioned symptoms were abdominal pain, genital discharge, foul smelling discharge, pain on urination, genital ulcers/ sores, swellings in groin area. Concerning symptoms of STI in men 265 (67.9%) of respondent mention at least one symptom of STI in men the common mentioned symptom in men were genital discharge, burning pain during urination, genital ulcers/sores and swellings in groin area.

The overall comprehensive knowledge score out of eight questions were calculated by summing the score of each item and one hundred eighty seven (47.9%) of the respondents had good knowledge of STI and the rest two hundred three (52.1%) of respondent had poor knowledge of STI.

Female sex workers’ STI care seeking behavior

Among the respondents 218 (55.9%) have utilized STI care services for different reason in the past 12 month prior to the study. Among users of STI care services 80 (36.7%) have utilized the service of treatment purpose, 69 (31.6%) for screening purpose the rest visited for consultation service and condom receiving 36 (16.5%) and 32 (14.7%) respectively.

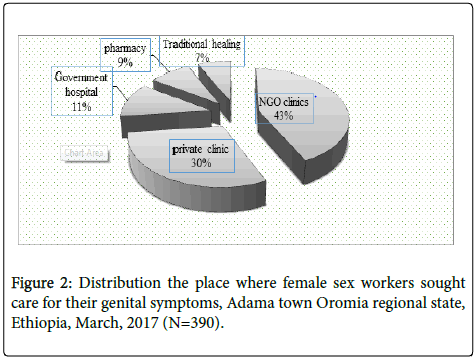

Out of 276 respondents who had history of STI symptoms, only 142 (51.4%) sought some form of treatment for their condition. When asked for the place where they sought treatment, 61 (43.0%) sought treatment in NGO clinics, 43(30%) private clinic, 16 (11.3%) government hospital, 12 (8.5%) pharmacy, the rest 10 (7%) sought treatment from traditional healing as shown in Figure 2.

Among those who had sought care 78% of the respondents had visited health care within 1 month of symptom recognized. Those FSWs who hadn’t sought care for their genital symptoms mentioned different barriers in utilizing the services, negative staff attitude, lack of privacy, long waiting time and high cost of treatment were the most frequently mentioned barriers in utilizing the service.

Measurements of theoretical constructs

With respect to measurement of the theoretical constructs respondents score high perceived barrier followed by perceived benefit which is 3.77 and 3.28, respectively. The mean score of the rest of the theoretical constructs are depicted by Table 3.

| No | Theoretical constructs | No utilized STI care service | Utilized STI care service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||

| 1 | Perceive susceptibility | 3.2 | 0.86 | 3.82 | 0.75 |

| 2 | Perceive severity | 3.14 | 0.9 | 3.88 | 0.78 |

| 3 | Perceive benefit | 3.28 | 0.91 | 4.02 | 0.74 |

| 4 | Perceived barrier | 3.77 | 1.03 | 3.78 | 1.05 |

| 5 | Cue to action | 3.06 | 0.9 | 3.84 | 0.8 |

Table 3: Mean and standard deviation of theoretical constructs scores of female sex workers working in licensed drinking establishments of Adama town Oromia regional state, Ethiopia, March, 2017 (N=390).

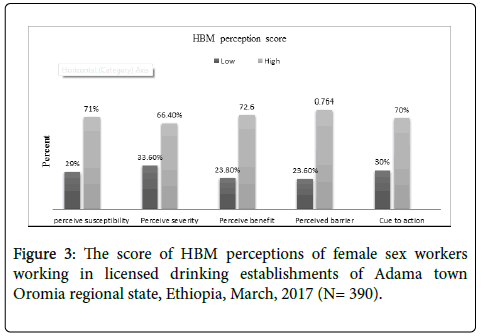

As shown in the above table respondents perceive a fear high score for all health belief model perception. When the theoretical construct dichotomized in to high and low depending on the mean score, majority of the respondent had high level of HBM perception as shown in Figure 3.

Predictors of STIs care seeking behavior in bivariate logistic regression

In the bivariate logistic regression all potential explanatory variables namely educational status, marital status, any family to support, duration of sex work, having non- paying sexual partner, condom use with non-paying client, condom use with non-paying client, type of paying client in past two week, having history of STI symptom in the past 12 month and knowledge of STI, perceive susceptibility, perceive severity, perceive benefit, perceived barrier and cue to action were entered in the bivariate logistic regression discretely to detect the effect of individual explanatory variable on the likelihood of STI care service utilization. Among the variables examined in binary logistic regression ten variables such as educational status, duration of sex work, having non- paying sexual partner, type of paying client in past 2 week, having history of STI symptoms in the past 12 month and knowledge of STI, perceive susceptibility, perceive severity, perceive benefit and cue to action were the variables with p value less than 0.25 and become candidate variables for the final multivariate logistic regression analysis. The rest variables namely, marital status, any family to support, condom use with non-paying client, condom use with paying client and perceived barrier show no association with STIs care service utilization (P value ≥ 0.25).

Predictors of STIs care seeking behavior in multivariate logistic regression

In the final backward conditional multivariate logistic regression analysis all the variables with P-value<0.25 in bivariate logistic regression namely educational status, duration of sex work, having non- paying sexual partner, type of paying client in past 2 week, having history of STI symptoms in the past 12 month and knowledge of STI, perceive susceptibility, perceive severity, perceive benefit and cue to action were entered. Thus, the final model demonstrates that Perceive susceptibility (P-value=0.022), perceive severity (P-value=0.001), cue to action (P-value=0.002), knowledge (P-value<0.001), having STI symptoms (P-value<0.001), having non-paying sexual partner (Pvalue= 0.023)and duration of sex work (P-value=0.013) as the most significant factors that were significantly associated with STI care seeking behavior among female sex workers. Variables such as educational status, type of paying client in past 2 week, perceived barrier and perceive benefit failed to show significant association with STI care seeking behavior among female sex workers.

Female sex workers with high score of perceived susceptibility for STI were 2.3 times more likely had STI care seeking behavior than those with low score of perceived susceptibility[AOR 2.330, 95% CI (1.130,4.802)], female sex workers with high score of perceived severity for STI were 3.25 times more likely had STI care seeking behavior than those with low score of perceived severity [AOR 3.257 95% CI (1.655,6.411)], female sex workers with high score of cue to action 2.8 times more had STI care seeking behavior than those with low score of cue to action [AOR 2.821, 95% CI 2.821 (1.464,5.439)]. Regarding the modifying variables, female sex workers with high score of knowledge were 5.36 times more likely had STI care seeking behavior than those with low score of knowledge [AOR 5.364, 95% CI (3.080,9.340)], female sex workers who had history of STI symptoms were 3.9 times more likely had STI care seeking behavior than those without symptoms[AOR 3.953, 95% CI (2.180,7.167)], female sex workers who had non-paying sexual partners were 1.9 times more likely had STI care seeking behavior than those without non-paying sexual partner [AOR 1.956, 95% CI (1.097, 3.485)] and female sex workers staying in the business for more than 3 years were 0.5 times less likely had STI care seeking behavior than those working 1-3 years [AOR 0.500, 95% CI (0.290,0.862)]. The final multivariate logistic regression model that depict variables which significantly predict STI care seeking behavior among female sex workers are summarized by Table 4.

| Variables | Not Utilized n (%) | Utilized n (%) | COR | AOR at 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceive susceptibility | ||||

| Low perceive susceptibility | 88 (77.9%) | 25 (22.1%) | 8.088 | 2.330(1.130,4.802)* |

| High perceive susceptibility | 84 (30.3%) | 193 (69.7%) | ||

| Perceive severity | ||||

| Low perceive severity | 99(75.6%) | 32 (24.4%) | 7.883 | 3.257 (1.655,6.411)* |

| High perceive severity | 73 (28.2%) | 186 (71.8%) | ||

| Cue to action | ||||

| Low cue to action | 88 (75.2%) | 29 (24.8%) | 2.821 | 2.821 (1.464,5.439)** |

| High cue to action | 84 (30.8%) | 189 (69.2%) | ||

| Knowledge of STI | ||||

| Poor knowledge | 138 (68.0%) | 65 (32.0%) | 9.554 | 5.364 (3.080,9.340)** |

| Good knowledge | 34 (18.2%) | 153 (81.8%) | ||

| Had STI symptoms | ||||

| Had no STI symptom | 72 (63.2%) | 42 (36.8%) | 3.017 | 3.953 (2.180,7.167)** |

| Had STI symptom | 100 (36.2%) | 176 (63.8%) | ||

| Non-paying sexual partner | ||||

| No | 65 (53.7%) | 56 (46.3%) | 1.757 | 1.956 (1.097,3.485)* |

| Yes | 107 (39.8%) | 162 (60.2%) | ||

| Duration of sex work | ||||

| 1-3 Years | 88 (38.9%) | 138 (61.1%) | 0.607 | 0.500 (0.290,0.862)* |

| 3> Years | 84 (51.2%) | 80 (48.8%) | ||

*means P value <0.05 and **means P value <0.01; Note: The table shows only significant variables after controlling for educational status, type of paying client in the past 2 week, perceived benefit and perceived barrier; For all the variables the first category was taken as a reference group.

Table 4: Multivariate logistic regression of socio-demographic and theoretical variable of the study subject with dependent variable, Adama town Oromia regional state, Ethiopia, March, 2017 (N=390).

Discussion

It appears from the study that 55.9% of female sex workers stated that they personally subject themselves to health institution for STI concern (for treatment, consultation, for receiving condom etc). This proportion is similar with the study undertaken in Davangere city, Central Karnataka 51.2% [22,23] and Nairobi, Kenya 49.3% [24] and lower than study undertaken in Ogun State, Nigeria in which majority of the female sex workers 80.9% had used STI care service [25]. This may be due to the non-existence of female sex worker friendly service in public facilities in the study area. Among female sex workers with previous STI symptoms 48.6% of the study subjects did not seek care for their genital symptoms. This is consistent with study undertaken in Kano, Nigeria 46% and India 48.3% [26,27] suggesting that majority of them with STI symptoms did not seek care for their genital symptoms. However, among those that sought care, 68.9% did so at greater than one month after self-recognizing the symptoms. Delay in seeking STI care service among female sex workers were also evidenced by other studies conducted in Uganda 73.6% and Angola 66.7% [10,11]. This delay in utilizing STI care service may be due to the perceived stigmatization and discrimination by the female sex workers in those countries. Lack of or a delay in utilizing STI care service result in missed opportunities to manage STI, as STI care providers can directly deliver interventions such as treat

The most frequently mentioned barrier in utilizing STI care service were negative staff attitude, lack of privacy, long waiting time and high cost of treatment. Similar hurdles were identified as barriers to care seeking behavior among female sex workers in other studies carried out in Kigali, Rwanda and Loas [28,29]. In this study majority of the female sex workers with STI symptoms sought STI care service predominantly from the private sector and NGO clinics, seldom from the public sector. These finding is consistent with other studies conducted regarding care seeking for STI symptoms among sex workers in Pakistani [30] and Parades, India [31]. This similarity may be due to the fact that public health facility found in those countries my not provide favorable institutional environment that can suit MARPs specifically female sex workers.

Regarding condom utilization more than 59.7% had used a condom consistently with paying clients during the past 12 month prior to the study. This finding is congruent with the study conducted in Adama on work-related violence and inconsistent condom use [32] and Bangladesh [33]. Majority of the Female sex workers (69%) had nonpaying sexual partners among them 60.8% used condom consistently, when having sex with their non-paying sexual partners during the past 12 month prior to the study. This implies female sex workers use condom in the same pattern when having sex with their paying and non-paying client. Disparity in condom usage pattern between paying and non-paying client has been evidenced by other studies conducted in Blantyre, Bahirdar and Adama [34-36]. The more likely explanation for this discrepancy in finding might be attributable to the roll of NGO run confidential clinic found in Adama town. This may possibly have significant impact on the attitude of female sex workers towards condom utilization with both paying and non-paying client.

Genital symptoms (genital discharge 30.8%, burning pain during urination 20% genital ulcers/sore 18.5% and swelling in groin area 15.4%) were common among the female sex workers. This finding is comparable with other study undertaken in Rwanda and Pakistan [29,30], suggesting high prevalence of STI among female sex workers and consequently this signify a high potential for STI and HIV transmission among this group.

Concerning HBM perceptions, the study revealed that majority of the female sex workers had high score of perceived susceptibility for STI (71%), perceived severity for STI (66.4%), perceived benefit of STI care service utilization (72.6%), perceived barrier for STI care service utilization (76.4%) and cue to STI care service utilization (70%). Other studies that applied HBM in explaining HIV screening behavior among female sex workers, reveals the same finding in which majority of female sex workers scored high for all of the HBM perceptions [37,38].

This study considered a range of potential predictors including socio-demographic, sexual behavior, knowledge, perceived susceptibly, perceived severity, perceived benefit, perceived barrier and cue to STI care service utilization. Seven variables (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, cue to action, knowledge, having symptoms, having non-paying sexual partner and staying in the business for more than 3 years were strong predictors of STI care seeking behavior. In this study having good knowledge of STI were positively associated with STI care seeking behavior among female sex workers (P value<0.001) similar study conducted in among female sex workers in Peru and Senegal substantiated this finding [36,37].

The likelihood of STI care service utilization were positively associated with having history of one or more of the STIs symptoms (P value<0.001). Other studies conducted in Ohio, America, Bangladesh, India sustained this finding [38]. Which means asymptomatic female sex worker tends to visit health institutions less often than those who had already noticed the symptoms. This might implies that female sex workers usually contemplate themselves as healthier as long as they don’t recognize the symptoms. The finding of this study indicated that female sex workers staying in the business for more than 3 years were less likely to utilize STI care service than those with 1-3 year experience. This result is in agreement with the study conducted in loas [28]. This may be for the fact that staying in the business for a long period makes them dispirited and feel less responsiveness for their health concern.

Generally, the majority of respondent in this study perceived a high level of perception for all HBM constructs. Perceive susceptibility perceive severity and cue to action were the constructs that significantly associated with STI care seeking behavior. Female sex workers with high score of perceived susceptibility, perceived severity and cue to action were more likely had STI care seeking behavior than those with low score. This study is unique because it uses HBM to depict a STI care seeking behavior. As per the investigators knowledge currently there is very limited literature concerning how the components of the Health Belief Model predict STI care seeking behavior and whether the HBM is appropriate for elucidating STI care seeking behavior among female sex workers. Due to this limitation in literature the study fails to compare and contrast the finding of HBM theoretical dimensions.

Conclusion

Sixty percent of the female sex workers visit health institution for STI apprehension most of them were predisposed by self-recognized STI symptoms. Among those with history of STIs symptoms majority sought care from NGO clinics and private health facilities. There were several barriers mentioned by those female sex workers who hadn’t sought treatment for their genital symptoms. The barriers were related to both structural and individual factors comprising long waiting time in the clinic, high cost of treatment, judgmental attitudes of healthcare providers and lack of privacy.

The behavioral schematic design (HBM) was employed in this study. The results found that 3 of the Health Belief Model perceptions perceived susceptibility, perceived severity and cue to action were significantly associated with STI care seeking behavior. High perceived susceptibility, High perceived severity and High cue to action were positively associated with STI care seeking behavior. Other variables like having symptoms of STIs, good knowledge of STI, having nonpaying sexual partners were positively associated with STI care seeking behavior. Duration of sex work greater than 3 years was negatively associated with STIs care seeking behavior.

Author’s Contributions

Hailemariam Shewangizaw designed the study, trained data collectors and managed data collection. Nigusse Aderajew, Hailemariam Shewangizaw, Kebed Alemi conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript and provided input into data analysis and overall study progress. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author’s deepest gratitude and sincere appreciation goes to Adama FGAE confidential clinic staffs that were cooperative in offering imperative information. Author’s would like also to thank all voluntary female sex workers that were enthusiastically take part in the data collection process. I want to acknowledge the 4th Annual Congress and Medicare Expo on Primary Healthcare and Nursing for providing opportunity to present the paper.

References

- Pankhurst R (2017)The history of prostitution in Ethiopia. J Ethiop Stud 12: 159-178.

- Article 634 (1994) The criminal code of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia. Proclamation.

- International FH (2002) Mapping and census of female sex workers in family health international (FHI )-Ethiopia Addis Ababa city administration health bureau (AACAHB).

- Overs C (2014) Sex workers, empowerment and poverty alleviation in Ethiopia.

- Rojanapithayakorn W (2006) The 100% condom use programme in Asia. Reprod Health Matters 14: 41-52.

- Ngugi EN, Roth E, Mastin T, Nderitu MG, Yasmin S, et al. (2012) Female sex workers in Africa: Epidemiology overview, data gaps, ways forward. Sahara J 9: 148-153.

- Bank Thew (2008) The global HIV/AIDS program the world bank HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia: An epidemiological synthesis.

- Richard S, TeodoraEW, Anatoli K, Francis N (2009) Control of sexually transmitted infections and prevention of HIV transmission: Mending a fractured paradigm. Bull World Health Organ 87: 858-865.

- Adu-oppong A, Grimes RM, Ross MW, Risser J, Kessie G (2007) Social and behavioral determinants of consistent condom use among female commercial sex workers in Ghana. AIDS Educ Prev 19: 160-172.

- Vera A (2014) STI care service utlization by female sex workers Uganda 28: 496-512.

- Jeal N, Salisbury C, Turner K (2008) The multiplicity and interdependency of factors influencing the health of street-based sex workers: A qualitative study. Sex Transm Infect 84: 381-385.

- Chacham AS, Diniz SG, Maia MB, Galati AF, Mirim LA.(2007) Sexual and reproductive health needs of sex workers: Two feminist projects in Brazil. Reprod Health Matters 15: 108-118.

- Jeal N SC (2004) Self-reported experiences of health services among female street-based prostitutes: A cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 54: 515-519.

- Esler D, Ooi C, Merritt T (2008) Sexual health care for sex workers. Aust Fam Physician 37: 590-592.

- Dixon-Woods M, Stokes T, Young B, Phelps K, Windridge K, Shukla R (2001) Choosing and using services for sexual health: A qualitative study of women’s views. Sex Transm Infect 77: 335- 339.

- Ward H, Day S (2006)What happens to women who sell sex? Report of a unique occupational cohort. Sex Transm Infect 82: 413-417.

- Republic FD (2015) National guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections using syndromic approach. Ethiopia.

- Towns FA, Negele A (2007) Oromiya region first baseline assessment for mobile HIV counseling and testing program first assessment towns: Dukem, Bishoftu.

- Marketing S (2003) Report on sex workers population size estimation in seventeen towns of Ethiopia.

- Mitike G (2005) HIV/AIDS behavioral surveillance survey (BSS) Ethiopia 2005 round two. Addis Ababa.

- Magnani R, Sabin K, Saidel T, Heckathorn D (2005) Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance 2: S67-S72.

- LW, Hunt SB, DiBrezzo R, Jones C (2004) Design and implementation of health belief model.

- Girish HO, Kumar A, Balu PS (2014) A study on STI morbidity pattern and STI treatment seeking behavior among female sex workers of Davangere city, central Karnataka. Int J Life Sci Biotechnol Pharma Res 3: 254-260.

- Fonck K (2008) Sexually transmitted infections in Nairobi, Kenya: Doctoral thesis submitted to the faculty of medicine and health sciences promotor.

- Adeneye AK, Mafe MA, Adeneye AA, Adeiga AA (2016) Health-seeking behaviour of brothel-based female sex workers in the management of sexually transmitted infections in urban communities of Ogun. Int J Womens Health Care 1: 1-6.

- Lawan UM, Abubakar S, Ahmed A (2016) Risk perceptions, prevention and treatment seeking for sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS among female sex workers in Kano, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 16: 61-67.

- K KJ, K DV, Singh TH (2005) STI care seeking behavior among female commercial sex workers, India. BMC Public Health 26: 26-32.

- Phrasisombath, Ketkesone  (2012) Female sex workers in Laos: Perceptions, care seeking behaviour and barriers related to sexually transmitted infection services Ketkesone. Department of public health sciences.

- Veldhuijzen NJ, Steijn M Van, Nyinawabega J, Vyankandondera J, Kestelyn E, et al. (2013) Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections , genital symptoms and health-care seeking behaviour among HIV-negative female sex workers in Kigali , Rwanda. Int J STD & AIDS 139-143.

- Khan AA, Naghma-e-Rehan, Qayyum K, Khan A (2001) Care seeking for STI symptoms in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 59: 628-630.

- Saggurti N, Mishra RM, Proddutoor L, Kovvali D, Parimi P, et al. (2013) Community collectivization and its association with consistent condom use and STI treatment-seeking behaviors among female sex workers and high-risk men who have sex with men/transgenders in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS Care 25: S55–S66.

- Mooney A, Kidanu A, Bradley HM, Kumoji EK, Kennedy CE, et al. (2013) Work-related violence and inconsistent condom use with non-paying partners among female sex workers in Adama City, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 13: 771.

- Admassu BA (2004) Magnitude of and factors associated with male condom use and failure rate among commercial sex workers of Bahir Dar town licensed non–brothel establishments, Ethiopia.

- Twizelimana D, Muula AS (2015) HIV and AIDS risk perception among sex workers in semi-urban Blantyre. Tanz J Health Res 17: 1-7.

- Workagegn F, Kiros G, Abebe L (2015) Predictors of HIV-test utilization in PMTCT among antenatal care attendees in government health centers: Institution-based cross-sectional study using health belief model in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2013. HIV/AIDS(Auckl) 7: 215-222.

- Trieu SL, Modeste NN, Marshak HH, Males MA, Bratton SI (2008) Factors associated with the decision to obtain an HIV test among Chinese / Chinese American community college women in northern California. Cal J Health Promot 6: 111-127.

- Hughes JP, Mejia C, Garnett GP, King K(2016) STI screening uptake and knowledge of sti symptoms among female sex workers participating in a community randomized trial in Peru. Int J STD AIDS 27: 402-410.

- Ward H, Day S (2013) Predictors of STIs utilization in among female sex workers in Senegal. Sex Transm Infect.

Citation: Shewangizaw H, Aderajew N, Alemi K (2019) STI Care Seeking Behavior and Associated Factors among Female Sex Working in Licensed Drinking Establishments' of Adama Town Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia 2017, by Employing Health Belief Model. J Community Med Health Educ 9: 656.

Copyright: © 2019 Shewangizaw H, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 2846

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Nov 23, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2180

- PDF downloads: 666