Review Article Open Access

Socioeconomic Determinants of Antimalarial Drug Use Behaviours: A Systematic Review

Philip Emeka Anyanwu, John Fulton*, Timothy Paget, Etta Evans

Applied Sciences , University of Sunderland, Sunderland, SR1 3SD, UK

*Corresponding Author:

- John Fulton

Faculty of Applied Sciences

University of Sunderland, Sunderland

SR1 3SD, United Kingdom

Tel: +44 191 515 2529

E-mail: john.fulton@sunderland.ac.uk

Received date: May 05, 2016; Accepted date: May 23, 2016; Published date: May 30, 2016

Citation: Anyanwu PE, Fulton J, Paget T, Evans E (2016) Socioeconomic Determinants of Antimalarial Drug Use Behaviours: A Systematic Review. J Comm Pub Health Nurs 2:123. doi:10.4172/2471-9846.1000123

Copyright: © 2016 Anyanwu PE, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

Abstract

Introduction: Malaria has been a major global health issue for centuries. Presently, the Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACTs) is the most effective antimalarial drug and the recommended first line treatment by the WHO for uncomplicated malaria cases. Despite the current global reduction in malaria mortality and morbidity, the burden of malaria is still very significant, especially considering the economic, social, political and public health effects to endemic countries. A major threat to sustaining the reduction in malaria burden is the development and spread of resistance to antimalarial drugs by the Plasmodium parasites (mostly P. falciparum and P. vivax). Socioeconomic factors have been identified to affect antimalarial drug use behaviours. Nevertheless, the contributions of socioeconomic factors to antimalarial drug use behaviours have only been sparsely reported in studies; with most of the studies not primarily designed to identify or assess the association of these variables. In addition there is no existing systematic review of studies on the socioeconomic determinants of antimalarial drug use. Therefore, there is an important need for a systematic review to integrate the findings from the different primary studies so as to provide an insight into the interaction between these variables.

Methods

Search: A systematic search of literature on the socioeconomic factors associated with antimalarial drug use behaviours was conducted in May, 2015. The following databases were searched: PubMed, EMBASE, Sociological Abstracts, Biomedical and Science Direct. A hand search was also conducted. Appraisal of the studies was conducted using the Principles of Critical Appraisal for Quantitative Studies (PCAQS) recommended by the Cochrane Library.

Synthesis: This study adopted a narrative approach in synthesising the results from individual included studies using a vote count table. This approach was the ideal for integrating the data considering the type of data extracted from the studies and the need to achieve the aim of this review.

Results: The synthesis of the findings from all the studies revealed different socioeconomic factors reported in relation to antimalarial drug use behaviours. These socioeconomic actors were categorized into Educational level (10 studies); Level of income/wealth (6 studies); Type of settlement (3 studies); Ability to read (2 studies); Occupation/Source of income (2 studies); and Household size (1 study). These factors were reported in line with antimalarial drug use behaviours such as non-adherence (12 studies); self-medication/presumptive diagnosis (5 studies) and non-compliance with malarial treatment guideline (4 studies). Educational level and income were the most reported socioeconomic factors. Most of the studies reported a significant relationship between higher educational level and adherence.

Discussion: Educational level was the most reported socioeconomic factor in relation to antimalarial drug use behaviours. This relationship between educational level and antimalarial drug use is further explained when one considers the level of poor education in some of the malaria endemic areas where there have been widespread of resistance to antimalarial drugs in the past. As a key socioeconomic factor, educational level has the ability to influence other socioeconomic factors. Some of the reasons given by participants for non-adherence (such as saving drugs for future use, sharing drugs, no food to administer drugs) as reported in some of the studies reviewed are less likely to occur among individuals of high socioeconomic status. There is need to integrate the concept of socioeconomic development in the design of strategies and policies to control antimalarial drug resistance.

Keywords

Antimalarial drug; Socioeconomic factor; Malaria

Background

vMalaria has been a major global health issue for centuries. Its burden goes as far back as the period before the discovery of the causal protozoan parasite in the 19th century by Alphonse Laveran in Algeria [1]. It is a preventable and treatable tropical disease caused by Plasmodium parasites transmitted through the bites of Anopheles mosquitoes [2].

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) guideline for malaria treatment, the core objective of treatment of uncomplicated malaria is to eliminate the malaria parasite from the body [3]. Presently, the Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACTs) is the most effective antimalarial drug and the recommended first line treatment by the WHO for uncomplicated malaria cases [2]. This recommendation has been adopted by over forty (40) African countries [4].

Evidently, malaria is inextricably linked to poverty. The causal link between malaria and poverty runs in both directions with the high burden of malaria identified as a driving factor in further impoverishment of people in endemic countries; and poverty being a major contributory factor in malaria infection [5-8]. No wonder the burden of malaria is highest in the poorest countries of the world [5-9].

Despite the current global reduction in malaria mortality and morbidity [2], the burden of malaria is still very significant, especially considering the economic, social, political and public health effects to endemic countries. A major threat to sustaining the reduction in malaria burden is the development and spread of resistance to antimalarial drugs by the Plasmodium parasites (mostly P. falciparum and P. vivax ).

Several factors play important roles in the development and spread of resistance. These factors include drug use practice/behaviour, drug half-life, transmission intensity, clone multiplicity, parasite density, host immunity, within-host dynamics and the genetic basis of drug resistance [10]. Amongst all, antimalarial drug use practice is a very important factor as it is attributed to human behaviour/activities, and can affect some of the other factors.

Furthermore, human behaviours in relation to antimalarial drugs use are influenced by the interaction of several external factors. Socioeconomic factors have been identified to affect not just the incidence of severe malaria [11] but also malaria treatment behaviours. Socioeconomic factors like income level can be key determining factor in treatment seeking and drug use behaviours of individuals and households. Relative to the level of poverty in malaria endemic countries, the high cost of antimalarial drugs - like the ACTs class of drugs - leads to drug use behaviours such as not using the recommended class of drugs [12], use of monotherapies, nonadherence to treatment regimen [13], presumptive and self-treatment [14-16] amongst others.

In addition, other socioeconomic factors like educational level, the type of settlement and ability to read have been reported to be associated with adherence to the treatment dose and regimen [17-21]. It is also important to mention that low socioeconomic status (SES) is a common feature in the Thai-Cambodia area which has been serving as the major hub of development and subsequent spread of resistance to most antimalarial drugs [22].

Nevertheless, the contributions of socioeconomic factors to antimalarial drug use behaviours have only been sparsely reported in studies; with most of the studies not primarily designed to identify or assess the association of these variables [15,17,19,21,23-25]. In addition there is no existing systematic review of studies on the socioeconomic determinants of antimalarial drug use. Therefore, there is an important need for a systematic review to integrate the findings from the different primary studies so as to provide an insight into the interaction between these variables. This will help to create a holistic picture on the role of socioeconomic factors in promoting behaviours associated with the development and spread of antimalarial drug resistance and how best to control resistance so as to preserve the effectiveness of antimalarial drugs.

This study conducted a rigorous review of existing studies that have reported on socioeconomic determinants of antimalarial drug use behaviours with the aim of identifying and creating an understanding of the key socioeconomic factors that play important roles in decisions and behaviours when using antimalarial drugs.

Research Questions

• What are the socioeconomic factors associated with antimalarial drug use behaviour?

• How can these socioeconomic factors affect the way antimalarial drugs are used?

• How can the identified malaria treatment seeking and drug use behaviours contribute to antimalarial drug resistance?

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic search of literature on the socioeconomic factors associated with antimalarial drug use behaviours was conducted in May, 2015. The following databases were searched: PubMed, EMBASE, Sociological Abstracts, Biomedical and Science Direct. Keywords for the search included terms for socioeconomic factors (e.g. Poverty, income, treatment cost, educational level, rural area, occupation, unemployment) together with terms related to antimalarial drug use behaviours (e.g. malaria drug adherence OR compliance, malaria drug use, antimalarial non-adherence OR non-compliance). In addition to the computerized search, a hand-search of relevant peer-reviewed journals as well as reports/publications from malaria organizations and charities was carried out.

Inclusion criteria

In order to achieve the aim of this review, the following criteria were used in the selection of relevant articles:

• Measured antimalarial drug use behaviours in relation to socioeconomic factors.

• Published between the years 2005 to 2015 so as to include studies conducted in a similar economic era as present.

• Reported drug use behaviour for any of the antimalarial drugs in use.

• Studies conducted in Africa or Asia.

• Explicitly stated the research methods and defined the characteristics of the socioeconomic index as used in the study.

• Quantitative method of research or collected quantitative data.

• Included caregivers, parents or adults who bear the financial and social cost of malaria treatment for themselves or a member of their household.

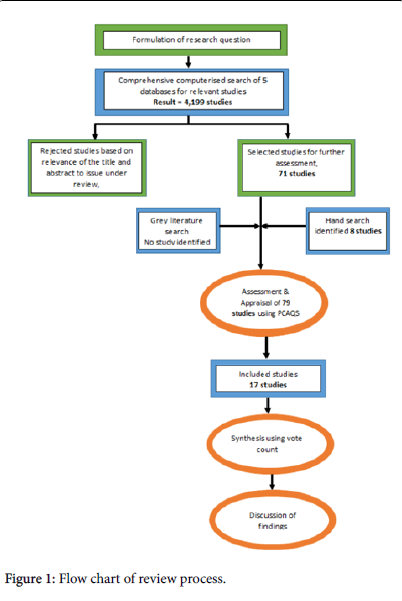

The computerized search of all the databases used for this study yielded a total number of 4,199 articles. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance with studies that did not report on socioeconomic factors in relation to drug use behaviour variables being excluded. This screening process was also conducted independently by the second author and a final narrow down to 71 articles was achieved.

The hand search was conducted by searching through journals on malarial research (like Malaria Journal, Malaria Nexus) for publications between the year 2005 up to 2015; checking the reference list of selected articles, the studies that have cited them and also related studies. The hand search process yielded 8 studies which were added to the 71 studies identified from the computerized search making a total of 79 studies.

Also, search of grey literature, including organizational sources -like reports and publications from World Health Organization, Malaria Consortium, African Leaders Malaria Alliance, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and Medicine for Malaria Venture-, conference proceedings, academic thesis among others was carried out. However, no relevant study was identified from this exercise. The 79 studies were further appraised for quality and relevance (See Figure 1 for flowchart of the search process).

Critical Appraisal for quantitative studies (PCAqs), as recommended by the Cochrane Library, was used in carrying out the appraisal exercise in this review. This guideline, which focuses on the critical appraisal of quantitative studies for validity and reliability, was used as a checklist for evaluating the quality of each of the studies. Firstly, this review appraised the appropriateness of the study population and participants. Studies that used participants like healthcare providers were excluded as this group are less likely to provide adequate and valid information on antimalarial drug use behaviours of patients and its socioeconomic determinants.

Furthermore, the data collection tool and process used in the studies were appraised. The indicators used for this appraisal were: objectivity of the measurement instrument, appropriateness of the process of participant recruitment, dissemination and administration of measurement instrument. As most of the studies from the search used questionnaire for data collection, we considered the dissemination and administration methods used by each study in relation to the context of the study population to determine the effectiveness of the methods in collecting valid information from participants. Studies that used dissemination methods like postal or internet in settings where these methods were not popular and where there was no existing systems to support their use were considered as weak.

In quantitative studies, the issue of external validity (generalizability) is very important in determining the extent to which the findings of a study are true representation of the target population. To ensure that externally valid studies are included in this review, we considered the sample size of each study in the appraisal process -as having a representative sample will ensure the generalizability of the study to the target population. Studies that did not clearly report how the sample size was calculated were considered weak in this category.

At the end of the assessment and appraisal exercise, seventeen (17) studies [14-21,23-31] that were of good quality based on the PCAqs assessment were included in this systematic review.

Synthesis

This study adopted a narrative approach in synthesising the results from the individual studies included. This approach was ideal for integrating the data considering the nature of the extracted data (in terms of the statistical analysis conducted); and the need to achieve the aim of this review.

Prior to the synthesis, relevant data from studies included were extracted using a data extraction sheet. This was conducted by the first author independently, and then cross checked by the second author to ensure all data relevant to the review were extracted. An agreement was reached on the data finally extracted and used in the synthesis. Apart from the results, details of the studies, including the year of publication, source/publication house, study design and setting, as well as the number and type of participants, were also extracted. As this study aims at identifying socioeconomic determinants of antimalarial drug use behaviours, and considering the nature of the data extracted, a vote count synthesis was adopted as it is most appropriate method for synthesizing the quantitative data in this review (Table 1).

| Variables | Expected outcome | Unexpected outcome | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not acquiring the required dosage/regimen of drug and SES | 60.9% of participants (from low SES villages) did not buy full dosage. 67.3% gave reason as financial/affordability; 16.8% got better after starting; 14.4% said symptoms were mild and hence no need buying full dosage [31] | [31] | |

| 60.9% of participants did not buy full dosage of drug. Reasons given for this include: 67.3% could not afford, 16.8% got better after taking few tablets, 14.4% said symptoms were mild and so there was no need of buying full dosage [23]. | [23] | ||

| Adherence and education | P=0.024 with 22% more adherence in participants with secondary education [29] | Caretaker’s educational level and reported adherence showed no statistically significance (p=0.354) [35] | [26-29,32-37] |

| P=0.005 with participants with = 7yrs of formal education more likely to adhere [26] | Participants educational level was not associated with reasons for non-adherence (p=0.825) [32] | ||

| P<0.01; OR 0.074; 95% CI 0.017-0.322. higher education level was associated with ACT adherence [28] | There was no statistically significant association between the educational level of patients or caregivers and probably adherence (p=1.00) [37] | ||

| Uptake of IPTp-SP increased with education, from as low as 38.9% among those who had no education to as high as 52.3% among those with secondary and higher education. Women with secondary and higher education were almost twice as likely as those who had never been to school for formal education to receive complete IPTp-SP doses (RRR=1.93, 95% CI 1.04 - 3.56). (P <0.001) [34] | No association between educational level and adherence/non-adherence [27] | ||

| The adjusted odds of completed treatment for those who has finished primary school was 1.68 times that of patients who has not (95% CI: 1.20, 2.36; P=0.003) [36]. There was a statistically significant association between fathers’ attainment of tertiary (higher education) and use of ACTs, when compared to fathers who had not attained this level of education (OR 0.054, CI 0.006-0.510; P=0.011) [33] | No significant for mothers’ attainment of tertiary (or higher) education and the use of ACTs (OR 0.905, CI0.195-4.198; P=0.898). [33] | ||

| Adherence and income | P=0.003; OR 0.340; 95% CI, 0.167-0.694. higher income level (Ksh>9000 (i.e.,>GBP 66 monthly) was associated with ACT adherence [28] | [22,24,28,35,39] | |

| P=0.034 with participants of higher income salary showing correct dosage of drugs [24] | |||

| Initiation of home treatment was higher in the poorer households. 25% of the poorest will use home treatment first as against 14% in wealthiest SE category [22] | |||

| In addition, household monthly income significantly influenced dosage of the drugs used (P=0.034) primarily due to the fact that higher proportions of respondents with an income salary of KShs. 4500-9000 (48.5%) took the correct dosage of drugs as opposed to individuals with below KShs 4500 and above KShs 9000 [39] | |||

| Caretakers from the third SES quintile were most likely to adhere to treatment compared to the first quintile [35] | |||

| Adherence and ability to read | P<0.01 OR 0.285; 95% CI 0.167-0.486. Ability to read was associated with ACT adherence [28] | [29] | |

| However, ability to read was statistically significant to number of antimalarial tablets left (p=0.049) [29] | |||

| Adherence in urban and rural | 96% of rural dwellers would not administer appropriate dosages [25] | 65% of urbanites would use incomplete dose. Only 35% would administer correctly [3] | [14,24,25,35] |

| The consumption of ACTS was more in the urban areas for both adults (P value=0.001) and children (P value=0.005) [24]. | Participants’ residence and reported adherence showed no statistically significant relationship (p=0.428) [35] | ||

| Self-diagnosis was the most common diagnostic method in both rural and urban for adult and child diagnosis. There was higher proportion of self-diagnosis in rural than in urban areas for both adults and children. Rural self-diagnosis (Adult=89.7%; children=85.9%), Urban self-diagnosis (Adult=83.3%; Children 79.2%) [24]. | |||

| Urbanites are more likely to have blood test malaria diagnosis than rural dwellers [24] | |||

| Adherence and source of drugs | P=0.005 those who source from pharmacy/chemists and government institutions were more likely to take correct dose than those from street vendors, private clinics, family/friends [24] | [24] | |

| Self-diagnosis/medication and SES | 20% of rural dwellers will self-medicate first [25] | 79% of the urbanites will use self-medication first [3] | [22,24,25,28,31,34] |

| 25% of poorest SES will use home treatment first [22] | 14% of wealthiest SES will use home treatment first [5] | ||

| 61.6% took antimalarial drugs without prescription [31] | |||

| Self-diagnosis was slightly higher in rural adults and children (A=89.7%; 85.9%) than in urban adults and children (A=83.3%; C=79.2%) [34] | |||

| Those in the poorer SES groups were however more likely to have previously sought treatment for their current illness prior to seeking treatment at the study facilities (p=0.002). Of these, 62.7% used the patent medicine dealers [38] | |||

| Self-diagnosis was the most common diagnostic method in both rural and urban for adult and child diagnosis [24] | |||

| Reasons for self-medication | 39.0% said less expensive than consultation; 10% said health institution was far away; 12.5% said neighbour/friend/relative previously took the same drug [31] | [23,31] | |

| For those who had no prescription, the reasons given were as follows: 39.0% said procedure of acquisition (without prescription) was less costly; 23.0% took same drug for similar symptoms; 10% said health institution was far from their location; 12.5% said neighbour/friend/relative previously took the same drug [23]. | |||

| Presumptive diagnosis and SES | 46% of rural dwellers will use drug vendors [25] | [25,34] | |

| Urbanites were more likely to have blood test than rural dwellers [34] | |||

| Non-adherence and reasons given | 14.7% of 34 interviewed [27] | [23,27,31] | |

| No food available for drug administration; and Sharing drugs with others | 16.2% of 144 who were non adherent [31] | ||

| Saving drug for future illness | Reasons for not taking drugs according to advice were mainly; 41.4% kept drugs for future episodes of the same illness, 33.0% got better hence discontinued, and 16.2% shared the dosage with another person (23) | ||

| Nearness to treatment source | P=0.001 with the poorest SES more likely to travel further to seek treatment [38] | [38] | |

| Household size and adherence | Household size significantly influenced the types of anti-malarial drugs used (b=0.092, P=0.049). A higher proportion of the respondents whose household sizes were 3-5 (68.9%) or =6 (20.1%) used SP as compared to households with 1-2 individuals (11.0%) (P=0.015) [39] | [39] | |

| Source of income/occupation and adherence | HH source of income significantly influenced duration of antimalarial drug use (P=0.050) with higher proportion of respondents who were salaried (21.9%) or self-employed (38.6%) reporting using antimalarial drugs within the specified duration relative to those with other sources of income (like farming, casual worker and petty trade) [39]. | [24,34,39] | |

| Occupation of respondents was statistically significant to none uptake of IPTp-SP (p=0.040) with participants who were farmers/livestock keepers (29.4%) and those with no job (29.0%) more likely not to take IPTp-SP than those employed/self-employed (18.8%) [34] | |||

| P=0.050 HH source of income was associated with adherence with salaried and self-employed more adherent than others like farmers, casual workers & petty traders [24] |

Table 1: Vote count.

Vote counting is a quantitative approach in systematic review that comprises of the identification and counting of the frequency with which a specific variable(s) is reported in all the included papers; and the use of the percentages or frequencies in drawing conclusions about the issue under review [32]. The vote counting process for each of the variables reported in this review involved identifying the number of included papers that reported the variable and also considering the outcome and the strength of the statistical test for significance.

Results

The data extracted from these studies were all quantitative data. Survey research design was the most adopted research design by the included studies (about 80%) - which was mostly cross-sectional with few longitudinal surveys. Only one of the 17 studies was conducted outside Africa (in Myanmar, Asia). Five studies were conducted in Tanzania; four studies each from Kenya and Nigeria, while Uganda, Ethiopia and Sierra Leone had one study each. Majority of the studies were conducted in rural areas, however, few were conducted in both rural and urban areas as well as urban areas only

The synthesis of the findings from all the included studies revealed different socioeconomic factors reported in association with antimalarial drug use behaviours. These socioeconomic factors were include Educational level (10 studies); Level of income/wealth (6 studies); Type of settlement (3 studies); Ability to read (2 studies); Occupation/Source of income (2 studies); and Household size (1 study). Most of the studies reported on more than one socioeconomic factor. These factors were reported in line with antimalarial drug use behaviours such as non-adherence/non-compliance with treatment guideline (16 studies) and self-medication/presumptive diagnosis (5 studies).

Definition used for ACT adherence

The definition of adherence was moderately standard across the included studies. Majority of the studies defined adherence as patients’ administering the antimalarial drug according to the recommendations. In determining adherence, two common tools used by the studies were: counting the remaining tablets/pill in the blister pack and/or verbal report of how many doses taken and at what time. About three studies added other measures like ‘if medication was administered with or without food’ and ‘the duration of the treatment’.

Measurement tool used for categorization of income/wealth level

For the studies that reported on income level and adherence, the Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to classify income and wealth. However, there were differences in the inputs used for calculating the PCA. The inputs reported in all the studies on income/ wealth level include educational status of the household head or caregiver, data on household assets, housing construction and main source of drinking water.

Statistical significance

For all the included studies, statistical significance was determined at p value of 0.05 and below.

Educational level and antimalarial drug use behaviour

Educational level was the most reported socioeconomic factor in relation to antimalarial drug use behaviour across the studies. More than half of the studies (10 studies) reported on educational level in relation to adherence. Nine of these studies were conducted in the African region [18-21,24-28] while one study was conducted in Southeast Asia [29]. There was a high level of uniformity in the measurement tool used to assess educational level. Most of the studies used the classification of - no formal education; primary; secondary and tertiary education. One of the 10 studies [18] used a classification of ‘no education; 1-7years of education; and >7 years’ to report educational level.

The findings on educational level were not consistent in all the studies. Six studies [18,20,21,25,26,28] reported a statistically significant relationship between higher educational level and adherence; four studies [19,24,27,29] reported no statistically significant relation24ship between the variables.

In quantitative research, using small number of participants (hence low statistical power) can lead to findings that may be nominally statistically significant but do not reflect the true effect [38-40]. To ensure that the interpretation of effects of the findings (using statistical significance) is not misleading, this review compared the sample size for studies reporting both statistically and no statistically significant relationship between educational level and adherence. The sample size in the studies that showed statistically significant relationship were between 217 to 1,267 while for those with no statistically significant relationship were between 73 to 444.

Income/socioeconomic level and antimalarial drug use behaviour

Income level was the second most reported socioeconomic determinant across the included studies. Six studies [14,20,23,27,30,31] reported on the association between income level and antimalarial drug use behaviours of non-adherence to the treatment dosage [20,27,31] and non-compliance to treatment guideline in the form of self-medication [15,23,30]. All of these studies were conducted in Africa.

Of the three studies that reported on income level and adherence, two [20,31] found a statistically significant relationship between low income level and non-adherence. The other study [27] did not conduct a statistical analysis of this relationship, but used percentages to indicate less-adherence in lower socioeconomic levels.

Of the three studies that reported on income/wealth level and noncompliance, only one study [30] tested this relationship using statistical analysis and found a relationship between poorer socioeconomic status and presumptive treatment. The other two studies [15,23] only reported a higher percentage of presumptive treatment among poorer households.

Source of income/occupation and antimalarial drug use behaviour

Among all the included studies, only two studies [26,31] reported on sources of income or type of occupation in association with adherence to malaria treatment. These two studies reported statistical association between the source of income/occupation and adherence.

Ability to read and antimalarial drug use behaviour

Two studies [20,21] reported on adherence to antimalarial treatment and ability to read. Both studies found a statistically significant association between ability to read and adherence to antimalarial drugs.

Type of settlement and antimalarial drug use behaviour

In all, four studies [16,17,26,27] looked at antimalarial drug use behaviour between different types of settlements. Settlements in the four studies were categorized into two –urban and rural. The studies were conducted in Nigeria and Tanzania (two studies from each of the locations). Three studies reported on self-diagnosis/treatment [16,17,26] while two reported on adherence [17,27].

Amongst the studies that reported on self-diagnosis/treatment, two studies [17,26] found a statistically significant relationship between the type of settlement and self-treatment/medication. The study by Exavery et al. [26] reported that rural dwellers were more likely to selfmedicate than urban dwellers. The other study which was conducted by Oguonu et al. [17] reported a contrast finding with urban dwellers more likely to self-medicate than the rural dwellers.

In studying the relationship between type of settlement and adherence, one study [17] reported a higher proportion of nonadherence (96%) among rural dwellers compare to urban dwellers (65%); it however did not conduct a statistical analysis to determine the significance of this relationship. In addition, the other study that reported on adherence and type of settlement [27] found a statistically insignificant relationship between type of settlement and adherence.

Household size and antimalarial drug use behaviour

Only one study [31] reported on household size and antimalarial drug use behaviour. The study, which was conducted by Watsierah et al. [31] found that household size significantly influenced type of antimalarial drugs used; with a higher proportion of the respondents whose household sizes were 3-5 or = 6 more likely to use the outdated first-line treatment of SP (monotherapy) compared to households with 1-2 individuals (p=0.015).

Reasons for non-adherence and self-medication

Non-adherence to the antimalarial treatment regimen and noncompliance to the recommended treatment guideline through selftreating or presumptive diagnosis were the most reported drug use behaviours. Some of the included studies that reported these behaviours also reported some reasons given by participants for these behaviours.

For non-adherence, the reasons reported include: No food available for drug administration [19]; sharing drugs with others [23]; and saving drugs for future [15].

For self-treatment and presumptive diagnosis reasons given include: Less expensive than consultation [15,23]; and Health institution too far from home [15].

Discussion

The socioeconomic factors reported by the studies included in this review are all key challenging issues in malaria endemic countries. These factors play important roles in decisions on where to seek treatment, the type of antimalarial drugs to choose, adherence to the prescriptions, completion of the treatment course amongst others. Among the socioeconomic factors reported in the reviewed studies, educational level reportedly plays a key role in determining antimalarial drug use behaviours.

The relationship between educational level and antimalarial drug use is further explained when one considers the level of poor education in some of the malaria endemic areas where there have been widespread of resistance to antimalarial drugs in the past. Using the Nigerian population as an example, about 30.1% of the population have no formal education [33]; the country also experienced widespread resistance to antimalarial drugs like Cholorquine and Sulphadoxine Pyrimethamine [12]. It is no co-incidence that this interaction between poverty, low level of education, poor treatment seeking behaviours, and spread of resistance exists in these malaria endemic populations.

In terms of making decisions on what drugs to buy, educational level can be a key determinant of the outcomes. An individual’s educational level can influence their level of knowledge and understanding of malaria, which can be a strong predictor of adherence [41]. Individuals who have at least basic formal education, and can read and write, will be more likely to spot out differences in the packaging of original and fake drugs (like incorrect spelling of the brand names of the drug in a fake). Also, the ability to confidently and correctly check the expiry date of antimalarial drugs before purchasing can be influenced by educational level. Similarly, people with little or no education are less likely to read prescriptions and instructions on how to take their drugs, hence they will rely more on their memory of verbal instructions from the caregiver to know the correct dose and time to administer.

Evidently, educational level is a key socioeconomic factor with the ability to influence other socioeconomic factors. An individual’s level of education can affect his/her ability to read and write, kind of job, income level, as well as the kind of settlement he/she might live in. This is evident in the fact that the two studies that reported a statistically significant relationship between the ability to read and adherence [20,21] also reported that participants with higher level of education were more likely to be adherent to antimalarial treatment. The ability to read can help patients to read and understand their prescriptions, know the appropriate dose to administer and at what time.

Also, of the three studies that reported that having a high income was associated with adherence to antimalarial drugs, two of the studies also reported that educational level affects adherence. In malarial endemic areas like Nigeria, with about 46% of the 178.5 million population living below the world bank poverty line [34], the cost of malaria treatment, which is about USD $2.9 for ACTs drugs alone in settings like Nigeria [12], can be a barrier to adhering to malaria treatment guidelines. The reasons given by participants for nonadherence (such as saving drugs for future use, sharing drugs, no food to administer drugs) as reported in some of the studies reviewed are less likely to occur among the educated and high income earners. Inability to afford the recommended antimalarial drugs encourages non-adherence through these survival or coping behaviours.

In addition, the behaviours of saving and sharing antimalarial drugs results to the administration of sub-therapeutic doses which encourage the development of resistance to antimalarial drugs by the Plasmodium parasites

Equally important is the association between the type of settlement and antimalarial drug use behaviour. A high proportion of the populations in malaria endemic countries reside in rural areas with less access to health facilities –for example, in Nigeria about 80.4% of the population reside in rural areas [33]. Although there were studies reporting a relationship between the type of settlement and adherence, however, there was no strong evidence from the reviewed studies to indicate that those in the rural or urban areas were more likely to misuse antimalarial drugs. Nevertheless, considering the small number of studies that reported on this association [16,17,26,27], the results included are not sufficient enough to make a conclusion on the effect of settlement types on antimalarial drug use behaviour. Despite the fact the relationship between household size and antimalarial drug use behaviour is not well reported in existing literature, however this socioeconomic measure cannot be ignored as a potential determinant of antimalarial drug use behaviours. In line with the study by Watsierah et al. [31] which was included in this review, other studies like Shayo et al. [35] have also found an association between the household number and health seeking behaviour.

Limitations of the Review

This review had some limitations. Firstly, it only included studies written in English language, although the search yielded only two studies written in French. Secondly, this review did not explore cultural barriers to adherence or the appropriate use of antimalarial drugs and antimalarial treatment practices of those who consult herbal practitioners.

Finally, with most of the included studies from Africa (~ 95%) and only one in Southeast Asia, the findings of this review might not represent the situations in malaria regions like the Southeast Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean regions. The reason for not including any study from the Eastern Mediterranean region is because there was no existing study from this region that met the inclusion criteria. The nonexistence of such studies in this region is understandable considering that only 2% of the global malaria burden occurs here [36]. According to the WHO malaria report 2015, the African (88%) and Southeast Asian (10%) regions remain the most burdened in terms of malaria infection.

Conclusion

Although several socioeconomic factors were reported to play important roles in determining antimalarial drug use behaviours, however, the most reported were educational level and income level. Adherence to malaria treatment course and compliance with treatment guidelines was reported to be significantly more among people with higher educational level; with people of lower education less likely to adhere to the treatment regime.

Recommendations

Given the evidence on the association between educational level and adherence, there is need to integrate this important variable in the design of strategies and policies to control antimalarial drug resistance. Policy makers should also consider adopting socioeconomic development as a strategy in the control of antimalarial drug misuse and resistance.

In addition, there is need for more studies that will focus on exploring, in details, the effects of these reported socioeconomic factors in determining how antimalarial drugs are used.

References

- Harrison G (1978) Mosquitoes, malaria and man: A history of the hostilities since 1880. Med Hist 23: 360.

- World Health Organization (2014) 10 fact sheets about malaria. Media centre.

- World Health Organization (2006) Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Bosman A,Mendis KN (2007) A major transition in malaria treatment: the adoption and deployment of artemisinin-based combination therapies, The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 77: 193-197.

- Teklehaimanot A, Mejia P (2008) Malaria and poverty.Ann N Y AcadSci 1136: 32-37.

- Ricci F (2012) Social implications of malaria and their relationships with poverty.Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 4: e2012048.

- de Castro M, Fisher M (2012) Is malaria illness among young children a cause or a consequence of low socioeconomic status? Evidence from the United Republic of Tanzania. Malaria Journal 11: 161-173.

- Tusting LS, Willey B, Lucas H, Thompson J, Kafy HT, et al. (2013) Socioeconomic development as an intervention against malaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 382: 963-972.

- Sachs J, Malaney P (2002) The economic and social burden of malaria.Nature 415: 680-685.

- Huijben S (2010) Experimental studies on the ecology and evolution of drug-resistant malaria parasites. University of Edinburgh.

- Zoungrana A, Chou YJ,Pu C (2014) Socioeconomic and environment determinants as predictors of severe malaria in children under 5 years of age admitted in two hospitals in Koudougou district, Burkina Faso: a cross sectional study. Acta Trop 139: 109-114.

- Ezenduka C, Ogbonna B, Ekwunife O, Okonta M, Esimone C (2014) Drugs use pattern for uncomplicated malaria in medicine retail outlets in Enugu urban, southeast Nigeria: implications for malaria treatment policy. Malar J 13: 243.

- Bloland P (2001) Drug resistance in malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Deressa W, Ali A, Berhane Y (2007) Household and socioeconomic factors associated with childhood febrile illnesses and treatment seeking behaviour in an area of epidemic malaria in rural Ethiopia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 101: 939-947.

- Watsierah CA, Jura WG, Raballah E, Kaseje D, Abong'o B, et al. (2011) Knowledge and behaviour as determinants of anti-malarial drug use in a peri-urban population from malaria holoendemic region of western Kenya.Malar J 10: 99.

- Onwujekwe O, Hanson K, Uzochukwu B, Ezeoke O, Eze S, et al. (2010) Geographic inequities in provision and utilization of malaria treatment services in southeast Nigeria: diagnosis, providers and drugs.Health Policy 94: 144-149.

- Oguonu T, Okafor HU, Obu HA (2005) Caregivers's knowledge, attitude and practice on childhood malaria and treatment in urban and rural communities in Enugu, south-east Nigeria.Public Health 119: 409-414.

- Beer N, Ali AS, Rotllant G, Abass AK, Omari RS, et al. (2009) Adherence to artesunate–amodiaquine combination therapy for uncomplicated malaria in children in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Tropical Medicine& International Health 14: 766-774.

- Gerstl S, Dunkley S, MukhtarA, Baker S, Maikere J (2010) Successful introduction of artesunate combination therapy is not enough to fight malaria: results from an adherence study in Sierra Leone. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 104: 328-335.

- Onyango EO, Ayodo G, Watsierah CA, Were T, Okumu W, et al. (2012) Factors associated with non-adherence to Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) to malaria in a rural population from holoendemic region of western Kenya. BMC infectious diseases 12: 143.

- Cohen J, Yavuz E, Morris A, Arkedis J, Sabot O (2012) Do patients adhere to over-the-counter artemisinin combination therapy for malaria? evidence from an intervention study in Uganda. Malaria Journal 11: 1475-2875.

- Wongsrichanalai C, Meshnick S (2008) Declining artesunate-mefloquine efficacy against falciparum malaria on the Cambodia–Thailand border. Emerging infectious diseases 14:716.

- Cohen JM, Sabot O, Sabot K, Gordon M, Gross I, et al. (2010) A pharmacy too far? Equity and spatial distribution of outcomes in the delivery of subsidized artemisinin-based combination therapies through private drug shops. BMC Health Services Research 10(Suppl 1):S6.

- Ogolla JO, Ayaya SO, Otieno CA (2013) Levels of adherence to coartem© in the routine treatment of uncomplicated malaria in children aged below five years, in kenya’.Iran J Public Health 42: 129.

- Akoria OA, Arhuidese IJ (2014) Progress toward elimination of malaria in Nigeria: Uptake of Artemisinin-based combination therapies for the treatment of malaria in households in Benin City. Annals of African medicine 13: 104-113.

- Exavery A, Mbaruku G, Mbuyita S, Makemba A, Kinyonge IP, et al. (2014) Factors affecting uptake of optimal doses of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy in six districts of Tanzania. Malaria Journal 13: 10-1186.

- Simba DO, Kakoko D, Tomson G, Premji Z, Petzold M, et al. (2012) Adherence to artemether/lumefantrine treatment in children under real-life situations in rural Tanzania. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 106: 3-9.

- Bruxvoort K, Kalolella A, Cairns M, Festo C, Kenani M, et al. (2015) Are Tanzanian patients attending public facilities or private retailers more likely to adhere to artemisinin-based combination therapy? Malaria Journal 14: 1-12.

- Win TZ, Zaw L, Khin W, Khin L, Tin OM, et al. (2012) Adherence to the recommended regimen of artemether-lumefantrine for treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Myanmar. Myanmar Health Science Research Journal 24: 51-55.

- Ibe OP, Mangham-Jefferies L, Cundill B, Wiseman V, Uzochukwu BS,et al. (2015) Quality of care for the treatment for uncomplicated malaria in South-East Nigeria: how important is socioeconomic status?. International Journal for Equity in Health 14: 19.

- Watsierah CA, Jura WG, Oyugi H, Abong'o B, Ouma C (2010) Factors determining anti-malarial drug use in a peri-urban population from malaria holoendemic region of western Kenya.Malar J 9: 295.

- Light R, Smith P (1971) Accumulating evidence: Procedures for resolving contradictions among different research studies. Harvard Educational Review 41: 429-471.

- Central Bank of Nigeria (2012) National financial inclusion strategy. Abuja: Central band of Nigeria.

- World Bank (2015) Country Profile.

- Shayo EH, Rumisha SF, Mlozi MR, Bwana VM, Mayala BK, et al. (2015) Social determinants of malaria and health care seeking patterns among rice farming and pastoral communities in Kilosa District in central Tanzania. Actatropica 144: 41-49.

- World Health Organization (2015) World malaria report 2015. Geneva: WHO.

- Blair E, Zinkhan GM (2006) Nonresponse and generalizability in academic research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34: 4-7.

- Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, Nosek BA, Flint J, et al. (2013) Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience.Nat Rev Neurosci 14: 365-376.

- Ioannidis JP (2005) Why most published research findings are false.PLoS Med 2: e124.

- Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U (2011) False-positive psychology undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological science.

- Gore-Langton GR, Alenwi N, Mungai J, Erupe NI, Eves K, et al. (2015) Patient adherence to prescribed artemisinin-based combination therapy in Garissa County, Kenya, after three years of health care in a conflict setting. Malar J 14: 125.

Relevant Topics

- Chronic Disease Management

- Community Based Nursing

- Community Health Assessment

- Community Health Nursing Care

- Community Nursing

- Community Nursing Care

- Community Nursing Diagnosis

- Community Nursing Intervention

- Core Functions Of Public Health Nursing

- Epidemiology

- Epidemiology in community nursing

- Health education

- Health Equity

- Health Promotion

- History Of Public Health Nursing

- Nursing Public Health

- Public Health Nursing

- Risk Factors And Burnout And Public Health Nursing

- Risk Factors and Burnout and Public Health Nursing

Recommended Journals

- Epidemiology journal

- Global Journal of Nursing & Forensic Studies

- Global Nursing & Forensic Studies Journal

- global journal of nursing & forensic studies

- journal of community medicine& health education

- journal of community medicine& health education

- Palliative Care & Medicine journal

- journal of pregnancy and child health

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 11944

- [From(publication date):

May-2016 - Dec 18, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11144

- PDF downloads : 800