Research Article Open Access

Social Functioning and Mental Wellbeing in 13- to 15-year-old Adolescents in Iran and Finland: A Cross-cultural Comparison

Jalal Khademi, Patrik Söderberg, Karin Österman and Kaj Björkqvist*Developmental Psychology, Åbo Akademi University, Vasa, Finland

- *Corresponding Author:

- Kaj Björkqvist

Developmental Psychology

Åbo Akademi University, Vasa, Finland

Tel: 358-45-8460100

E-mail: kaj.bjorkqvist@abo.fi

Received Date: Sep 30, 2016; Accepted Date: Feb 06, 2017; Published Date: Feb 16, 2017

Citation: Khademi J, Söderberg P, Österman K, Björkqvist K (2017) Social Functioning and Mental Wellbeing in 13- to 15-year-old Adolescents in Iran and Finland: A Cross-cultural Comparison . J Child Adolesc Behav 5: 333. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000333

Copyright: © 2017 Khademi J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate social functioning and mental wellbeing in 13-15 year-old adolescents in Iran and Finland, in order to explore potential cultural and gender-based differences during early adolescence. Methods: One thousand and one (1001) adolescents from Iran and 2205 adolescents from Finland (age range 13-15 years) filled in a questionnaire consisting of the following scales: the Mini Direct and Indirect Aggression Scale (Mini-DIA), the Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Children (SEQ-C), the School Burnout Inventory (SBI), and the Multidimensional Scale for Perceived Social Support Assessment (MSPSSA). Results: Iranian boys scored highest on Aggression, Victimization, and School Burnout, and lowest on Social Support, Academic Self-Efficacy, and Interpersonal Self-Efficacy. The Finnish boys scored highest on Interpersonal Self-Efficacy and Emotional Self-Efficacy, and lowest on School Burnout and Victimization. Finnish girls had the highest scores on Social Support and Academic Self-Efficacy, but the lowest on Aggression and Emotional Self- Efficacy. The Iranian girls did not have any highest or lowest scores in this sample. Conclusion: Clear differences due to culture and gender were found. It appears that Iranian boys, despite their higher societal status than girls, experience their school environment as more stressful than Iranian girls do, and than Finnish boys do as well. The findings are discussed.

Keywords

Adolescence; Aggression; Victimization; Self-efficacy; School burnout; Social support; Iran; Finland

Introduction

Research on psychosocial aspects of life in Iranian schools is still relatively scant. The overall aim of the present study was explorative, conducted in order to bring more light upon factors related to social functioning and mental wellbeing among Iranian adolescents in the school environment. More specifically, the prevalence of aggression, victimization from others’ aggression, school burnout, social support, and self-efficacy in 13-15 year-old students in Iran were investigated. For the sake of comparison with data from a Western country, data were also collected from adolescents in Finland, with the same research tools.

Although the overwhelming majority of Iranian adolescents are well-adjusted, a substantial group exhibits high levels of maladjustment and deficient functioning. Although aggressive and violent behaviors are not new in Iran, the recent escalation of criminal violence among the adolescent population has become a serious public health problem [1]. In the following, a brief review of previous studies in Iran on the topics covered in the present study will be provided.

Aggression problems: From the early 1970s, Iranian scholars have highlighted the side effects of youth and adolescent aggression [2]. A perfunctory review of Iranian newspapers and television talkshows reveals that violence, particularly violence perpetrated by youths, is of major concern in every sector of Iranian society. Accordingly, the prevalence of aggression among boys is higher than among girls [3]. In a casecontrol study conducted in 1991, the degree of anxiety, depression, aggression, and delinquency in 12- to 19-year-old adolescents from broken families was compared with that of adolescents from intact homes. It showed that girls from broken families were more depressed and anxious as compared to their male counterparts, who exhibited more aggressive and delinquent behaviors. The study did not offer any data pertaining to the prevalence of the problem. Later, in a survey of 800 high school children, the prevalence of aggression was estimated to be as high as 40% [4]. Without any attempt to show the prevalence of aggression, a survey of 498 intermediate students and their 43 teachers in Tehran indicated that verbal aggression was a common phenomenon among these students [5]. A study of 333 intermediate students in Tehran estimated the prevalence rate of aggression to be between 38% and 45% [6]. Another survey of 375 high school children in southern Iran showed that more than half of the students exercised verbal and physical aggression at school [7]. Another study conducted in the western region of Iran indicated that nearly 40% of high school students exhibited verbal and physical aggression [8]. A survey of 499 high school students in Hamadan showed that almost half of them (48%) were aggressive [9]. Meysamie et al. found among 1403 children attending 43 kindergartens that, according to parents’ ratings, the prevalence of physical, verbal, and indirect aggression was 9.9%, 6.3%, and 1.6%, respectively; while, based on teachers’ ratings, the same prevalence was 10.9% , 4.9%, and 6%, respectively [10].

Consequences of aggression: Childhood aggression may lead to severe social disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Aggression is a fundamental health problem in children and one of the most common reasons for referring children to mental health consults [11]. During childhood, aggression increases the chance of becoming a bully, bully/ victim, or victim [12]. It is also related to maladjusted behavior and undesirable social skills [13]. In addition, earlier aggression may lead to several behavioral and social disorders in adolescence and adulthood; for instance, alcohol and drug abuse, violence, depression, suicide attempts, spouse abuse, and neglectful and abusive parenting [14,15]. Longitudinal studies show that negative outcomes tend to be more severe in children whose aggressive behaviors were established already in early childhood in comparison to those children whose aggressive behaviors were established later on, during early adulthood [16].

School bullying: Bullying is one of the most common and serious forms of proactive aggression. Bullying is a group process, and therefore children involved may assume various roles, often beyond the role of a typical bully or victim [17]. Khezri et al., in a sample of 564 students from middle schools in Iran, found that 79.6% of pupils in some way - from mild to severe – had been involved in bullying and about 81% of these had been victims of bullying. In addition, 88% of the involved students were categorized as bully/victims. Findings also showed that 85% of boys and 72% of girls somehow - from mild to severe – had attempted to bully others. Approximately, 87% of boys and 73% of girls had sometimes been victims of bullying [18].

Victimization from school aggression and bullying: There are only few studies on the effect of being victimized from others’ aggression in Iranian schools. However, being a victim of school bullying may seriously affect the personality and behavior of those who are exposed to it. Peer victimization has distinguishable characteristics at individual, school, and environmental levels [19]. Victims reported greater truancy and lower Grade Point Average (GPA) than nonvictims. They also experienced social and psychological adjustment difficulties concurrent with their victimization [20].

School burnout: School burnout is a relatively new area of interest, and there is no internationally published article that has investigated school burnout in Iran. However, Marzoughi et al., in a study published in Persian (Farsi), found a relationship between lack of justice and equality in the class room and school burnout [21]. Kalantarkousheh et al., found that female students experienced more burnout than males. Ph.D. students had less experiences of academic burnout compared to students with other academic degrees [22].

Self-efficacy: Abazari et al., found that school commitment and school rewards for involvement had a significant negative association with multiple health risk behaviors [23]. In addition, Elahi Motlagh found that self-evaluation, self-directing and self-regulation are correlated with academic achievement [24]. The findings by Heidari et al., point out the importance of nurturing learners’ self-efficacy beliefs and its impact on successful learning experiences and achievement [25]. Asadi Piran found significant relationships between a positive self-concept and a reading comprehension scale, and between selfesteem and reading comprehension scores [26].

Social support: Roohafza et al., found a significant negative association between social support and acute coronary syndrome [27]. Cheraghi et al. found a significant relationship between perceived social support and quality of life [28]. However, Campbell’s analysis failed to support the hypothesis that perceived social support would moderate the effects of psychological distress on college adjustment [29].

The present study is explorative, investigating factors related to social functioning and mental wellbeing in Iranian adolescents 13-15 years of age. The investigated factors were peer aggression and victimization from peer aggression, school burnout, self-efficacy, and social support. For the sake of comparison with a Western society, the same factors were investigated in adolescents of similar age in Finland.

Method

Samples

Iranian sample: The Iranian sample consisted of 1001 pupils (659 girls, 342 boys) from 22 middle schools (120 girl schools, 12 boy schools) in Gorgan, a city with about 300 000 people, located in northern Iran. The mean age of the girls was 13.4 years (SD=0.5), and the mean age of the boys was 13.5 years (SD=0.6).

Finnish sample: The Finnish sample consisted of 2205 pupils from 23 middle schools in Ostrobothnia, a region in Western Finland. The mean age of the girls was 15.0 years (SD=0.7), and the mean age of the boys was 15.0 years (SD=0.7). The age difference between the two samples was significant [F(1,2801)=2192.85, p<0.001, ηp2=0.439]. Accordingly, age had to be treated as a covariate in the subsequent analysis.

Instrument

Data were collected by use of questionnaire, adapted from the Ostrobothnian Youth Survey (OYS) [30]. It addressed adolescent life in a specific region in Western Finland, Ostrobothnia, and it consisted of a number of scales measuring behavior both at home and at school. In the present study, results based on the following scales and subscales will be presented: a 3-item version of the Mini Direct and Indirect Aggression Scale (Mini-DIA) [31]; the Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Children (SEQ-C) [32]; the School Burnout Inventory (SBI) [33]; and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Assessment [34].The number of items of each scale, as well as Cronbach’s α-values as a measure of reliability, are presented in Table 1.

| Scales | Number of items | Iran α |

Finland α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression | 3 | 0.76 | 0.64 |

| Victimization | 3 | 0.76 | 0.64 |

| Social Support | 8 | 0.74 | 0.86 |

| School Burnout | 10 | 0.74 | 0.88 |

| Self-Efficacy-Academic | 7 | 0.74 | 0.85 |

| Self-Efficacy-Interpersonal | 7 | 0.68 | 0.84 |

| Self-Efficacy-Emotional | 7 | 0.76 | 0.90 |

Table 1: Reliability scores for the scales of the study

Procedure

Data were collected during regular school lessons, with one of the researchers or an assistant present. It took about one hour to fill in the questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

Data were collected under strict anonymity with the consent of school authorities and parents. As a whole, the study was conducted in accordance with required ethical standards by Åbo Akademi University.

Results

A two-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted with country (Iran vs. Finland) and sex (boys vs. girls) as independent variables, age as covariate, and the seven scales (aggression, victimization, social support, school burnout, academic self-efficacy, emotional self-efficacy, and interpersonal self-efficacy as dependent variables.

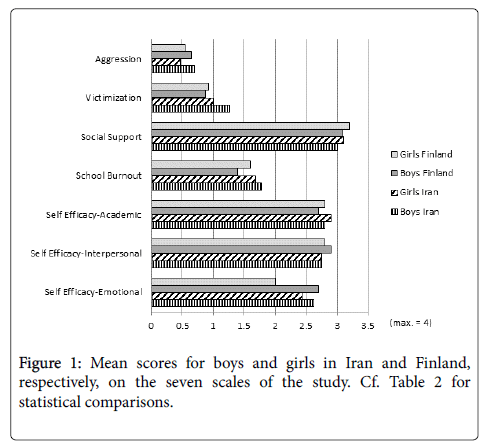

In this analysis, we witness a significant age and national difference between the Iranian and the Finnish samples. The results are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1.

| F | df | p ≤ | ηp2 | Group differences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Age (Covariate) Multivariate Analysis |

3.47 | 7, 1407 | 0.001 | 0.017 | |||

| Effect of Country | |||||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 2.75 | 7, 1407 | 0.008 | 0.013 | |||

| Univariate Analyses | |||||||

| Aggression | 3.26 | 1, 1413 | 0.07 | 0.004 | (Fi>Ir) | ||

| Victimization | 2.15 | ” | ns | 0.001 | |||

| Social Support | 2.67 | ” | 0.002 | 0.001 | Fi>Ir | ||

| School Burnout | 9.43 | ” | 0.001 | 0.001 | Ir>Fi | ||

| Self-Efficacy-Academic | 1.221 | ” | ns | 0.007 | |||

| Self-Efficacy-Interpersonal | 7.40 | ” | ns | 0.001 | |||

| Self-Efficacy-Emotional | 0.17 | ” | 0.066 | 0.002 | Ir>Fi | ||

| Effect of Sex | |||||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 21.65 | 7, 1407 | 0.001 | 0.097 | |||

| Univariate Analyses | |||||||

| Aggression | 15.19 | 1, 1413 | 0.001 | 0.001 | Boys>Girls | ||

| Victimization | 3.79 | ” | 0.052 | 0.004 | Boys>Girls | ||

| Social Support | 5.27 | ” | 0.022 | 0.000 | Girls>Boys | ||

| School Burnout | 0.39 | ” | ns | 0.004 | Girls>Boys | ||

| Self-Efficacy-Academic | 3.00 | ” | 0.083 | 0.000 | Girls>Boys | ||

| Self-Efficacy-Interpersonal | 2.51 | ” | ns | 0.002 | Boys>Girls | ||

| Self-Efficacy-Emotional | 91.28 | ” | 0.001 | 0.020 | Boys>Girls | ||

| Interaction Country x Sex | |||||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 5.88 | 7, 1407 | 0.001 | 0.028 | |||

| Univariate Analyses | |||||||

| Aggression | 1.13 | 1, 1383 | ns | 0.001 | I*) Boys high F**) Girls low |

||

| Victimization | 5.57 | ” | 0.018 | 0.004 | IBoys high F Boys low |

||

| Social Support | 0.01 | ” | Ns | 0.000 | |||

| School Burnout | 5.56 | ” | 0.023 | 0.004 | IBoys high F Boys low |

||

| Self-Efficacy-Academic | 0.02 | ” | ns | 0.000 | |||

| Self-Efficacy- Interpersonal | 2.42 | ” | ns | 0.002 | |||

| Self-Efficacy- Emotional | 29.00 | ” | 0.001 | 0.020 | F Girls low | ||

Table 2: Results from a 2 × 2 multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with country and sex as independent variables, age as covariate, and the seven scales of the study as dependent variables*) I = Iranian**) = Finnish. Cf. Figure 1.

As Table 2 shows, age would have affected the results if not kept as a covariate. The analysis determined that on some measures (Aggression, Victimization, Self-Efficacy Interpersonal and Self- Efficacy Emotional) boys had higher score than girls. On the remaining measures (Social Support, School Burnout, and Academic Self- Efficacy), girls had higher scores. The interaction between country and sex revealed that Iranian boys scored highest on Aggression, Victimization, School Burnout and lowest on Social Support, Academic Self-Efficacy and Interpersonal Self-Efficacy. The Finnish boys scored highest on Interpersonal Self-Efficacy and Emotional Self-Efficacy, but lowest on School Burnout and Victimization. As for girls, Iranian girls did not get any highest or lowest scores. However, Finnish girls had the highest scores on Social Support and Academic Self-Efficacy, but the lowest on Aggression and Emotional Self-Efficacy.

Discussion

In this study, factors related to social functioning and mental wellbeing in Iranian and Finnish adolescents 13-15 years of age were investigated. The dependent variables were aggression, victimization, school burnout, self-efficacy, and social support.

Boys and girls in Iran have a different life situation in family and society than in Finland. For instance, boys have more liberties than girls do, they can play outside of the house, and they do not need to cover up their whole body as girls do when wearing a hijab. They inherit twice as much as girls do. It is more acceptable for boys to have a girlfriend than it is for girls to have a boyfriend. Boys have more employment opportunities, and they get more chances in academic fields; in fact, some fields of study accept only boys. Moreover, aggression among boys is more acceptable than among girls. Since childhood, family, school, and the media start to bombard children with rules about acceptable and unacceptable roles of their gender. However, the difference in freedom between boys and girls is not the whole of the story. In Iranian families, girls are considered to be the most sensitive offspring in the family, and it is also believed that girls are more concerned about their parents, who thus receive indirect benefits from girls. For example, the likelihood of receiving positive feedback and emotional attention from parents in the form of hugs and kisses is higher for girls.

Girls serve to some extent as mediators between parents and male siblings in the family, which accounts for the high level of social support for girls in Iran. In addition, in Iran, doing military service is obligatory for boys (except for rare cases of exemption) and before fulfilling this obligation, boys do not receive any employment opportunities. The obligatory military service affects boys’ decision to attend university as well. Competing in the national higher education comprehensive entrance exam is the only way to be admitted to public universities, and this exam takes place right after high school graduation. Boys who fail in the entrance exam will automatically be drafted into military service. Accordingly, if they fail the exam, they must either apply for private universities or enroll into military service.

On the other hand, one of the essential gender-based rules for men is to earn money; thus, finding job is a big concern for boys. As a result of this pressure, annually a number of male students drop out of high schools to find a simple job as soon as possible. This fact also might explain the high level of school burnout in boys.

References

- Sadeghi S, Farajzadegan Z, Kelishadi R, Heidari K (2014) Aggression and violence among Iranian adolescents and youth: A 10-year systematic review. Int J Prev Med 2: 83-96.

- Ahmadi SA (1987) Psychology of the youth and adolescents. Nakhostin Publ, Tehran.

- Hasanzadeh, MT (2014) News about aggression and violence in Iranian boys and girls. Young Journalist Club.

- Golchin M (2002) Tendency toward aggression in adolescents and the role of family. J Gazvin Univ Med Sci 21: 36-41.

- Bazargan Z, Sadeghi N, Lavasani Gh (2003) Prevalence of verbal aggression among intermediate students in Tehran. J Psychol Educ 1: 1−28.

- Abdolkhaleghi M, Davachi A, Sahbaie F, Mahmoudi M (2004) Surveying the association between computer-video games and aggression in male students of guidance schools in Tehran, 2003. J Azad Univ Med Sci 15: 141-145.

- Elmi M, Tighzan KH, Bagery R (2010) Prevalence of aggression and its social correlates among intermediate students in Ajabshir city. Arch SID 2010.

- Lahsaeezadeh AA, Moradi GM (2012) Relationship between confrontation strategies and aggression in youth: A case study in Eslam Abad (W). Arch SID 2012.

- Sayarpur SM, Hazavee SM, Ahmadpana M, Moeni B (2012) Relationship between aggression and perceived self-efficacy among intermediate students in Hamadan. J Nurs Midwifery Hamadan 19:16-23.

- Meysamie A, Ghalehtaki R , Ghazanfari A, Daneshvar-Fard M, Mohammadi MR(2013) Prevalence and associated factors of physical, verbal and relational aggression among Iranian preschoolers. Iran J Psych 8: 138-144.

- Blake CS, Hamrin V (2007) Current approaches to the assessment and management of anger and aggression in youth: A review. J Child Adol Psych Nurs 20: 209-221.

- Jansen DE, Veenstra R, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Reijneveld SA (2011) Early risk factors for being a bully, victim, or bully/victim in late elementary and early secondary education. The longitudinal TRAILS. BMC Publ Health 11: 440.

- Campbell SB, Spieker S, Burchinal M, Poe MD, Network NECCR (2006) Trajectories of aggression from toddlerhood to age 9 predict academic and social functioning through age 12. J Child Psychol Psych 47: 791-800.

- Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Seguin JR, Zoccolillo M, Zelazo PD, Boivin M, et al. (2005) Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Can Child Adol Psych Rev 14: 3-9.

- Brame B, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE (2001) Developmental trajectories of physical aggression from school entry to late adolescence. J Child Psychol Psych 42: 503-512.

- Huesmann LR, Dubow EF, Boxer P (2009) Continuity of aggression from childhood to early adulthood as a predictor of life Outcomes: Implications for the adolescent- limited and life-course-persistent models. Aggr Behav 35: 136-149.

- Griffin, RS, Gross AM (2004) Childhood bullying: Current empirical findings and future directions for research. Aggr Viol Behav 9: 379-400.

- Khezri H, Ebrahimi Ghavam H, Mofidi F, Delavar A (2013) Bullying and victimization: prevalence and gender differences in a sample of Iranian middle school students. J Educ Manage Stud 3: 224-229.

- Salmivalli C, Lagerspetz K, Björkqvist K, Österman K, Kaukiainen A (1996) Bullying as a group process: participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggr Behav 22: 1-15.

- U.S. Department of Education (2008) Student victimization in US schools: Results from the 2005 school crime supplement to the national crime victimization survey.

- Marzoughi R, Heidari M, Heidari E (2014) Investigated the relationship between burnout and academic educational justice. J Med Educ Dev 2931: 328 -334.

- Kalantarkousheh SM, Araqi V, ZamanipourM, Mirzaee Fandokht O (2013) Locus of control and academic burnout among Allameh Tabataba'i University students. Int J Physical Soc Sci 3: 2249-5894.

- Abazari F, Haghdoost A, Abbaszadeh A (2013) The relationship between students' bonding to school and multiple health risk behaviors among high school students in south-east of Iran Iranian JPubl Health 43:185-192.

- Elahi Motlagh S, Amrai K, Yazdani ,MJ, Abderahim HA, Sourie H (2011) The relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement in high school students. Pro Soc Behav Sci 15: 765-768.

- Heidari H, Izadi M, Vahed Ahmadian M (2011) The relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ self-efficacy beliefs and use of vocabulary learning strategies. English language teaching 5: 2.

- Asadi Piran N (2014) The relationship between self-concept, self-efficacy, self-esteem and reading comprehension achievement: Evidence from Iranian EFL learners. Int J Soc Sci Educ5 : 2223-4934.

- Roohafza H, Talaei, Pourmoghaddas Z, Rajabi F, Sadeghi M (2012) Association of social support and coping strategies with acute coronary syndrome: A case-control study. J Cardiol 59: 154-159.

- Cheraghi MA, Davari Dolatabadi E, Salavati M, Moghimbeigi A (2012) Association between perceived social support and quality of life in patients with heart failure. IJN 25: 21-31.

- Campbell BAR (2013) Social support as a moderating factor between mental health disruption and college adjustment in student veterans. Univ North Texas.

- Söderberg P (2012) Ostrobothnian Youth Survey.Vasa, Finland: Dept Socl Sci, Åbo Akademi Univ.

- Österman K (2010) The Mini Direct Indirect Aggression Inventory (Mini-DIA). In: Österman K (Ed), Indirect and direct aggression. Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, Germany 103-111.

- Muris P (2001) A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. J Psychopath Behav Assess 23>45-149.

- Salmela-Aro K, Kiuru N, Leskinen E, Nurmi J-E (2009) School burnout inventory (SBI): reliability and validity. Eur J Psychol Assess 25: 48-57.

- Zimet, GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet, SG, Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 52: 30-41.

Relevant Topics

- Adolescent Anxiety

- Adult Psychology

- Adult Sexual Behavior

- Anger Management

- Autism

- Behaviour

- Child Anxiety

- Child Health

- Child Mental Health

- Child Psychology

- Children Behavior

- Children Development

- Counselling

- Depression Disorders

- Digital Media Impact

- Eating disorder

- Mental Health Interventions

- Neuroscience

- Obeys Children

- Parental Care

- Risky Behavior

- Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Societal Influence

- Trauma-Informed Care

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4188

- [From(publication date):

February-2017 - Jul 09, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 3294

- PDF downloads : 894