Review Article Open Access

Smoking Behavior in Arab Americans: A Systematic Review

Ghadban R1, Haddad L2*, An K1, Thacker II LR1 and Salyer J1

1School of Nursing, Virginia Commonwealth University, USA

2College of Nursing, University of Florida, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Linda Haddad, RN, PhD, FAAN

College of Nursing, University of Florida, 1225 Center Drive

Gainesville, FL, 32610, USA

Tel: 01-352-273-6520

E-mail: lhaddad@ufl.edu

Received date: August 03, 2016; Accepted date: August 19, 2016; Published date: August 25, 2016

Citation: Ghadban R, Haddad L, An K, Thacker II LR, Salyer J (2016) Smoking Behavior in Arab Americans: A Systematic Review. J Community Med Health Educ 6:462. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000462

Copyright: © 2016 Ghadban R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Background: In the United States (US), Arab Americans who maintain traditional cultural norms after their immigration are more likely to continue smoking as a form of social interaction. Arab Americans and their families are at a high risk for poor health outcomes related to smoking. Objective: This systematic review aimed to explore the smoking behavior, prevalence and use among Arab Americans and examine studies addressing the effect of acculturation on this behavior.

Results: The majority of the studies included focused on smoking prevalence and cessation. Some discussed the impact of acculturation and health beliefs on the smoking behavior of Arab American adolescents. Only two smoking cessation programs have been developed for Arab Americans, despite the high prevalence of both cigarette and water-pipe smoking in this community.

Conclusion: The scarcity of research on smoking among Arab Americans has impeded the development of interventions that improve health outcomes and reduce health disparities.

Keywords

Minorities; Arab-Americans; Acculturation; Health beliefs; Smoking

Introduction

Smoking is one of the most addictive habits and most preventable causes for a broad range of diseases including cancer, cerebrovascular diseases, coronary heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [1-5]. There is sufficient evidence to infer causal relationships between smoking and increased risk for at least ten types of cancers [1,3,4]. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) [6] report on research for universal health coverage notes that smoking is responsible for about six million deaths annually worldwide; more than five million of these deaths occur in primary smokers, and the remainder die as a result of secondhand smoke exposure. Despite the well-established harmful health effects of smoking, and the enormous efforts to reduce the prevalence of smoking, 20.5% of men and 15.3% of women in the US are currently smokers [7].

In the United States (US), minority status is associated with increased smoking rates among adults [7-9]. Individuals belonging to ethnic minorities may choose to accept or reject health behaviors based on their cultural beliefs, and such choices may be prime factors in their health. Consequently, there has been an increased interest in the role of cultural variables and their effect on smoking and cessation rates among various ethnic groups. In fact, according to the CDC [7], American Indians/Alaska Natives have the highest prevalence of smoking (31.4%), followed by African Americans (20.6%), Whites (21.0%), Hispanics (12.5%), and Asians (9.2%). Research shows that racial and ethnic status contributes to health disparities among minorities in the US.9 Arab Americans, who comprise a growing population in the US, have high rates of smoking prevalence (39%-69%) as well as low smoking cessation rates (11.1%-22.2%) when compared with national data [10-12], largely because smoking is a standard cultural behavior that Arab Americans continue after immigrating to the US. However, to date, and due to the classification of Arabs as “White,” there are no national data on Arab American smoking prevalence rates and only a few studies have examined smoking in Arab Americans, a vulnerable minority population at risk for poor health outcomes.

Acculturation is the complex and continuous process of interaction between two cultures that results in cultural and psychological changes [13-16] This interaction and its consequences on families, education, and health have been the primary focus of many sociological, psychological, and anthropological studies [16-18] Culture plays a major role in a person’s ideas about illness, disease, and health [19,20]. Immigration and acculturation are essential parts of US history. The US has drawn people from all over the world for countless reasons; as a result, America is rich in both multinational and multicultural diversity. In the 1880s an influx of European immigrants began, a trend that has continued up to the present and expanded to an even wider variety of immigrants, including Arabs. In fact, according to the Arab American Institute (AAI), [21,22] at least 3.5 million Americans are of Arab descent. The term Arab American is an overarching identity for many Arabs living in the USA. Although the term is simply defined as “the immigrants to North America from Arabic-speaking countries of the Middle East and their descendants” [22] there is a controversy regarding whether speaking Arabic is enough for a person to identify as an Arab. Many of the second, third, or fourth generations do not speak Arabic but still identify as Arab. The majority of Arab Americans have ancestral ties to Lebanon (34%), Syria (11%), Egypt (11%), Palestine (6%), and Iraq (3%) [22]. Arab Americans are found in every state, but more than two thirds of them live in just ten states (California, Michigan, New York, Florida, Texas, New Jersey, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia). One-third of the Arab-American population resides in metropolitan Los Angeles, Detroit, and New York [21].

Demographic information on Arab Americans is virtually nonexistent since the US government does not recognize them as a minority group [23] and classifies them as “White.” Because of this classification, Arab Americans continue to be culturally invisible [24]. Arab Americans tend to be young and well educated: more than 30% of the population is under 18 years of age; 22 89% have at least a high school diploma and 45% have a bachelor degree [21] About 60% of Arab American adults are in the labor force; 5% are unemployed and the median income for Arab American households in 2008 was $56,331 with 13.7% of the population living below the poverty line [21]. Recently, however, a few studies have been conducted among Arab-Americans and, more specifically, developed in relation to Arab- American history [22], identity [24,25], the impact of September 11, 2001, [26] feminism and sexuality [27,28], acculturation [25] and health [19].

Individuals from different cultures experience unique trajectories of acculturation. Furthermore, studies have provided evidence that risky health behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption are influenced by acculturation in these populations [29-34]. Most of the studies on these minorities found that acculturation may play a role in smoking among these populations and may account for this racial difference in their smoking rates [34-38]. It is well known that health disparities exist in the US, particularly among ethnic minorities [29]. Thus, in recent years, there has been a proliferation of research on human behaviors and practice based on minorities along with an emphasis from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to have more minorities included in research [39]. In current health research, however, most acculturation studies are generally conducted with Hispanic or African American minorities [36]. The purpose of this systematic review, therefore, was to examine current literature about smoking behavior, prevalence and use among Arab Americans; in order to help outline directions for future research in this understudied area of inquiry.

Methods

Protocol development

We developed the review protocol by stating all aspects of the review methods before starting the review. These included the following: inclusion criteria for studies, search strategy, screening method, abstraction, quality assessment, and data analysis. This aspect of the design was planned to minimize the effect of our possible bias on the review.

Eligibility criteria

Our inclusion criteria included: all kind of study designs (randomized controlled trials, non-randomized trials, observational studies, and qualitative studies) published in English. Studies did not need a minimum sample size to be included. Population: Arab individuals, Arab American groups, or Arab American communities. We Excluded studies reported as abstracts and for which we could not identify a full text after contacting the corresponding author. Additionally articles were excluded if they were conducted outside of the US or if they were literature reviews.

Search strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines [40] was used to conduct this literature search and review on Arab Americans and smoking. This systematic review evaluates research examining smoking behavior in Arab Americans. The review includes all studies that were published in English between January 1, 1990, and June 30, 2016. A systematic literature search was identified through the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, ScienceDirect, and Cochrane Library. Ancestry searches were used to identify any relevant studies that were not detected by the primary search. Because water-pipe smoking is a highly-prevalent behavior among Arabs and Arab Americans (practiced by an estimated 17% to 44.2% of this population) [10,41,42], studies that included water-pipe smoking or exclusively looked at water-pipe smoking behaviors among Arab Americans were also included. In addition, studies that included both adolescents and adults were included in this review. Studies were excluded if they were conducted outside of the US or if they were literature reviews.

The search terms included combinations of the following: “minorities,” [All fields] “Arab Americans,” [All fields] “acculturation,” [All fields] “health beliefs,” [Tittle/abstract] “smoking,” [All fields] “water-pipe,” [Tittle/abstract] “hookah,” [Tittle/abstract] “shisha,” [Tittle/abstract]” and “smoking cessation” [Tittle/abstract].

Data abstraction

The data abstraction form was piloted over 5 studies and used to abstract general information about the paper, where the study was conducted, study characteristics, populations studied, design features that affected the quality of the study and the validity of the results, outcome measures, and quality assessment data. Abstraction was performed in duplicate independently. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Data analysis

Two reviewers extracted data from the papers; the reviewers worked independently on each paper and then amalgamated the results. Discrepancies were resolved by referral back to the original papers and discussion. We did not combine the results of the studies because of the heterogeneity of design, outcomes, and populations. In our narrative analysis we consider the results in relation to the design and quality of the studies.

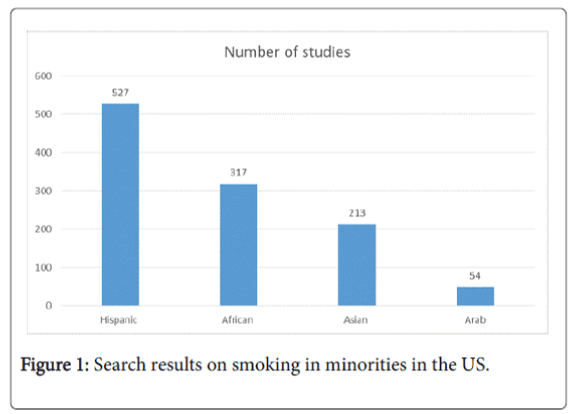

A total of 2105 studies were identified from databases and ancestry searches; 994 were excluded because of duplication, no-applicable titles and abstract review, resulting in 1111 studies on different minorities in the US: Hispanics/Latinos (n=527), African Americans (n=317), Asians (n=213), and Arab Americans (n=54) (Figure 1).

Results

For this systematic review, the 54 studies identified as relevant to Arab Americans were screened. 31 were excluded because they were conducted outside of the US and another two were excluded because they were literature reviews. Five other articles were identified from the ancestry searches and were included, resulting in a total of 26 studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

Study characteristics

Nineteen articles were cross-sectional studies investigating the different relationships between smoking behavior, smoking cessation, health beliefs, and acculturation, and 7 articles described two smoking cessation interventions (one in adults and one in adolescents) (Table 1). One study used a qualitative descriptive design with focus groups, and 25 studies used different quantitative designs. As for location, one study was conducted in California, one study was conducted in Colorado, two studies were conducted in Texas, 6 studies were conducted in Virginia, and 16 were conducted in the Midwestern region, near Michigan. All studies used convenience sampling and recruited participants from schools and/or faith-based centers (Islamic centers and mosques), Middle Eastern grocery shops, water-pipe bars, and/or health centers depending on the age of the targeted population and Internet. The sample size ranged from 8 participants (pilot intervention) to 3543 participants. In addition, 12 studies were conducted with Arab American adolescents and 14 were conducted with Arab American adults.

| Study (Refer to References List for complete citation) |

Study Design | Sample size & Characteristics | Study purpose/ Aims | Findings | Comments/ Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Faouri et al., 2005 | Instructional design | Arab Americans Health educatorsand students Group of students who were new immigrants | 1. To redesign Project Toward No Tobacco Use (TNT) to be culturally sensitive for Arab American youth. 2. To add health promotion and tobacco use prevention elements. 3. To develop an Arabic version of the revised program. 4. To develop a program guide for health educators on the instructional resources used in this project. |

Both the English and Arabic versions of the program were revised and evaluated during instructional development and application to make the necessary changes. A culturally sensitive multimedia Power- Point Arab-American Tobacco Use–Intervention Program (AATU-I) in English and in Arabic has been developed. |

Implementation and evaluation of its effectiveness is ongoing. |

| 2. Al-Omari&Scheibmeir, 2009 | Cross-sectional exploratory correlational design | Arab American smokers and ex-smokers N= 96 participants | To describe Arab Americans’ smoking behaviors and any relationship between tobacco dependence and acculturation. |

Arab Americans who are less acculturated to American norms view tobacco smoking as an acceptable behavior. The results support the body of literature that identifies a relationship between continued smoking behavior and living in a residence where smoking is tolerated. | The sample was nonrandomized and there was an overrepresentation of men in the sample. |

| 3. Alzyoud et al., 2014 | Pilot study Cross-sectional correlational design |

Self-identified Arab American Immigrants N= 221 Convenience sample |

1. To explore the possible patterns of Arab American waterpipe users, including current use, previous use, and intentions to quit. 2. To explore the relationship between acculturation and waterpipe smoking among Arab immigrants in the Richmond, VA metropolitan area. |

Higher rates of waterpipe use were found among males than females (66% versus 31.4%) No significant association between the type of tobacco used (exclusive versus dual) and desire or future intentions to quit waterpipe use. None of the proxy indicators of acculturation was significant for the entire sample. However, upon stratifying the results by group (exclusive vs. dual), exclusive waterpipe use was significantly correlated with proportion of life lived in the US (r(16)=0.56, p=0.02) as but the correlation remained not significant among dual smokers (r(23)=0.08, p=0.6). |

Further studies are needed to confirm the relatively high prevalence of waterpipe use among Arab Americans. There is a need to develop effective prevention strategies that will consider the acculturation process when trying to control the spread of waterpipe use among minority groups in the U.S. The limitations of this study include the use of a non-random sample. The acculturation association was assessed using a rough proxy measure instead of apsychometric tool. Finally, the measure of tobacco use was based on self-report only. |

| 4. Athamneh et al., 2015 | Observational cross-sectional study | Arab American adults N=340 Convenience sample |

1. To address waterpipe smoking in this ethnic minority. 2. To plan to control the growing epidemic in the general U.S. population. | The prevalence of having an intention to quit waterpipe smoking among this study sample was 27.43%. The intention to quit waterpipe smoking in this study sample was significantly lower with increasing age. Intention to quit waterpipe smoking was significantly higher with history of cigar use, a prior attempt to quit, and not smoking when seriously ill. Intention to quit waterpipe smoking was significantly lower with increasing age, medium cultural acceptability of using waterpipe among family, high cultural acceptability of using waterpipe among friends, longer duration of smoking sessions, and perceiving waterpipe smoking as less harmful than cigarettes. |

Inability to draw causal associations with such adesign. The study was conducted using a conveniencesample, thus the generalizability of the finding may be limited to the geographic area of the sample and not to all Arab Americans. The results relied on subject’s self-reported data, which might contain some potential sources of bias. |

| 5. Athamneh et al., 2016 | Observational cross-sectional study | Arab American adults N=340 Convenience sample |

To examine the theory of planned behavior (TPB’s) constructs’ effect on intention to quit water pipe smoking in the following 12 months among a sample of Arab Americans in the Houston area. | Behavioral evaluation, normative beliefs, and motivationto comply were significant predictors of an intention to quitwater pipe smoking adjusting for age, gender, income, maritalstatus, and education. | Efforts are greatly needed to design interventions andstrategies that include these constructs in order to help water pipe smokersquit and to prevent the potentially associated morbidity and mortality. |

| 6. Baker, 2005 | Descriptive correlational design | Arab Americans: Yemeni-American adolescents Males and females N= 297 Convenient sample |

To identify and describe relationships between selected predictors and tobacco use behavior in Yemeni-American adolescents by examining the personal and environmental factors of parental and peer tobacco use and the psychological factors of self-esteemand experimentation of tobacco use. |

Educational performance and family income has significantly positiveeffects on self-esteem, and peer influence has a significantly indirect effect on tobacco use. Age, parental smoking, and experimentation with tobacco have significantly positive effects on tobacco use. Educational performance has a significantly negative effect on it. |

The findings have implications for nursing and medical practice in the assessment and planning of culturally sensitive interventions to prevent tobacco use in Yemeni-American adolescents. Health professionals need to be aware of similarities and differences with the dominant culture when they are interacting with minority populations. |

| 7. Baker & Rice, 2008 | Descriptive correlational design |

American Arab Yemeni adolescents Males and females N= 297 Convenience sample |

1.To explore the relationships between the personal and environmental forces of parental and peer tobacco use and health risk action of tobacco experimentation and the psychological factor of self-esteem on waterpipe smoking. 2.To examine a cultural form of tobacco use (narghile/waterpipe smoking) and its relationship to self-esteem and to peer and family use. | 1. Adolescents’ use of narghile was associated with experimentation with tobacco. 2. The self-esteem variable did not contribute to predicting adolescents’ narghile use. 3. Age and peer smoking had an indirect effect on narghileuse. 4. The use of narghile was unrelated to parentaltobacco use in any form despite the strong family ties in this population. | To curtail and contain such health-risk behavior, it is apparentthat serious culturally specific intervention sessions, health education, and preventive measures should be implemented and applied effectively. To foster and benefit from such culturally specific interventions, the tobacco control community must work to correct the current misperceptions about thehealth risks of water-pipe smoking. |

| 8. El Hajj et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional, descriptive, and correlational study | Adult Arab Immigrants N= 100 Non-probable sample |

1. To examine tobacco use among Arab immigrants living in Colorado, whose socioeconomic status and health habits may be different from Arab immigrants living in other states. 2. To understand the effect of acculturation on tobacco use, both cigarettes and hookah, among the mentioned target population. |

1. Participants who were more integrated into Arab culture were more likely to use tobacco products and to have family members and friends who use tobacco products. 2. Acculturation plays a major role in affecting the health habits of Arab immigrants living in Colorado, especially in the area of hookah smoking. | The limitations of this study include the use of a non-probable sample. Understanding some culturally relevant predictors of tobacco use might assist health care providers in designing successful smoking cessation programs. |

| 9. El-Shahawy& Haddad, 2015 | Cross-sectional study | Arab immigrant smokers Self identified N=131 Convenience sample |

To explore the potential differences between exclusive cigarette smokers and dual smokers, in terms of nicotine dependence and barriers to cessation, among Arab Americans. | 1. There was significant difference between exclusive smokers and dual smokers in their FTND scores and Barriers to Cessation scores. 2. The correlation between the FTND scores and Barriers to Cessation scores remained significant only in the dual smokers group. 3. There was no significant correlation between barriers to cessation and desire to quitting or confidence in ability to quit smoking in either group, 4. Dual smokers had significantly more barriers to cessation than exclusive cigarette smokers. 5. There was a highly significant correlation among FTND scores, Barriers to Cessation scores, and past quit attempts among dual smokers. | Nonrandom sampling The study was conducted on Arab Americans; thus its results should be interpreted carefully when translated to other immigrant groups or the general population of exclusive cigarette and dual smokers. |

| 10. Haddad et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional exploratory study | Arab Americans N=221 Convenience sample |

To explore the cigarette use patterns including current use, beliefs and attitudes, and acculturation among Arab immigrants in Richmond. | 1. Cigarette Smoking rates were higher among the study sample than the general population of the state of Virginia. 2. Many smokers in this study had the desire to quit and attempted to quit. 3. Many initiated smoking at an early age. 4. The smokers in the study sample were not likely to be aware of the resources that could have helped them quit. 5. Acculturation indicators measured in this study were found to be positively correlated with the number of smoked cigarettes per day, as well as the number of attempts to quit by Arab immigrants. 6. The older an individual was when moved to the U.S. or the more time an individual had spent in the U.S. contributed significantly to the least number of quit attempts. | Non-random sample: further random sampling and study is needed to confirm the high prevalence of tobacco use among this minority group The acculturation effect was assessed using a rough proxy measure and not a proper psychometric tool. The identification of tobacco use and other related patterns that would be identified here may help facilitate the development of community based interventions targeting tobacco use and would be sensitive for Arab immigrants in future research. |

| 11. Haddad & Corcoran, 2013 | Pilot study Intervention study |

Arab American smokers Men N=8 Convenience sample |

1. To develop a culturally-tailored and linguistically-sensitive Arabic language smoking cessation program 2. To evaluate the feasibility of recruiting Arab Americans through a faith-based community organization which serves as a neighborhood social center. |

Out of 11 participants, eight decided they were ready to stop smoking and moved from Stage One, subsequently completing all five stages. The results suggest that it is possible to reach smokers from Arab American communities with a tailored Arabic language smoking cessation program | The findings of this report will be used as the basis for a large-scale intervention study of a culturally and linguistically sensitive cessation program for Arab American ethnic groups. The generalizability of the findings is potentially limited because a small sample of convenience was used. A self-report reduction and cessation instrument was used without any biological validation resulting in recall bias and inaccurate reporting. There was no randomized control group employed and no long-term follow-up involved, thus participants’ quit rates over time is not known. |

| 12. Haddad et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional study | Arab Americans Smokers N=154 Convenience sample |

1. To examine the barriers to cessation among dual users of cigarettes and waterpipe. 2. To increase our understanding of the barriers to cessation among dual users. 3. To gain perspective regarding the similarities and differences of either dual or exclusive smokers’ barriers to cessation and quitting behaviors. |

1. Dual smokers appeared to have more barriers to cessation than either of the other two groups: exclusive cigarette and exclusive waterpipe smokers. 2. Dual smokers appeared to have fewer concerns for the harm of smoking than exclusive smokers of either cigarettes or waterpipes 3. Exclusive cigarette and waterpipe smokers had similar mean barriers to quitting and were more concerned about their health than dual smokers. |

This study suggests a need for future research to focus on dual tobacco use, as it could become more prevalent and would pose specific challenges to cessation efforts. Convenience type of sampling is vulnerable to potential response biases that might affect the result thus limiting the generalizability of the study results. |

| 13. Islam & Johnson, 2003 | Cross-sectional survey study |

Arab Americans Muslim adolescents Males and females N=480 |

1. To examine the smoking prevalence. 2. To investigate the associations of known smoking risk factors, religious and cultural influences with adolescents’ susceptibility to smoking and experimentation with cigarettes among the ethnic group of Muslim Arab-American adolescents. |

1. Smoking rates reported in this survey are much higher than those previously reported byother researchers for the different ethnic groups of Arab youth. 2. There appeared to be similarities and variations in the associations between factors influencing susceptibility to smoking and those influencing experimentation for thissample of Muslim Arab-American adolescents. 3. Positive beliefs about smoking remained significantly associated with both susceptibilityand experimentation for both genders. 4. Perceived negative consequences significantly protected adolescents from susceptibility and experimentation. 5. Consistent with previous studies, being male was significantly associated with an increased risk of susceptibility and experimentation Cultural and religious factors investigated in this study appear to have a significant influence on adolescents’ smoking behavior. |

The results of this study are based on students’ self-reports of their smoking behavior. The results are also based on cross-sectional data, so causal influences cannot be determined. |

| 14. Jamil et al., 2009 | Cross-sectional exploratory study |

Three groups: Chaldean, Arab American and non-Middle Eastern White adults. N=3543 Convenience sample |

To compare and contrast personal characteristics, tobacco use (cigarette and water pipe smoking), and health states in Chaldean, Arab American and non-Middle Eastern White adults attending the same urban community service center. | 1. The three groups differed significantly on ethnicity, age, gender distribution, maritalstatus, language spoken, education, employment, and annual income. 2. Current cigarette smoking was highest for non-Middle Eastern White adults and current water pipe smoking was highest for Arab Americans. Arab Americans were more likely to smoke both cigarettes and the waterpipe. 3. Health problems were highest among former smokers in all three ethnic groups. 4. Being male, older, unmarried, and non-Middle Eastern White predicted current cigarette smoking; being Arab or Chaldean and having less formal education predicted current water pipe use. | A major limitation is the use of convenience sampling, it is not clear to what degree the sample, although it is a fairly large one, is representative of the populations from which it was drawn. Another concern was the uneven participation of the ethnic groups; the largest number were Arab Americans. There is a problem with the limited amount of information on tobacco use patterns and trajectories in these three ethnic groups. Another limitation is the limited amount of information on tobacco use patterns and trajectories in these three ethnic groups. |

| 15. Kassem et al., 2015 | Descriptive cross-sectional study |

Arab-American adults N= 458 Convenience sample |

To examine initiation, prosand cons of hookah tobacco smoking among Arab Americans. | Irrespective of sex, most participants initiated hookah tobacco use by young adulthoodin private homes or hookah loungesinfluenced by friends and family. Womeninitiated hookah use later than men. Ever dual smokers (hookah smokers who eversmoked a cigarette) initiated hookah uselater than cigarettes; however, early hookahinitiators < 18 years initiated hookahand cigarettes concurrently. Participantsenjoyed the flavors of hookah tobacco,and complained about coughing, dizziness,and headaches. |

Cross-sectional design which limits the ability to establish causality. A convenience sample was used; therefore, findingsof this study may not be generalizable to other Arab-Americans. Data were collected through selfreport,which is subject to social desirability response bias. |

| 16. Kulwicki& Rice, 2003 | Qualitative Focus group interviews |

Arab American adolescents N= 28 Convenience sample |

1. To gather information on Arab American adolescent tobacco use behavior. 2. To use the information to modify the Project Toward No Tobacco Use cessation program so that it would reflect the cultural values of Arab American youths. |

1. Sociocultural factors are considered key factors in smoking behavior of adolescents. 2. Participants identified one of the strongest barriers they experienced in trying to quit as their concern about hanging around friends who smoked. 3. Most adolescents participating in the focus group discussions were exposed to smoking at a young age. 4. Focus group participants had no difficulty obtaining cigarettes. 5. When asked about the dangers of smoking, almost all participants had knowledge about the dangers of smoking, but most did not care about the long-term negative effects. | The findings from this study have several implications for nurses designing and implementing tobacco use programs for Arab American adolescents. Cultural attitudes and behaviors, family and peer relationships, andpatterns of smoking are significant factors to take into consideration when developing a smoking cessation programs. |

| 17. Kulwicki et al., 2007 | Descriptive study | Pregnant women N= 830 (823 Arab Americans) | To determine the prevalence of smoking behavior in a select sample of Arab American women in order to eventually develop culturally appropriate prenatal health promotion and smoking cessation program for Arab American pregnant women. |

Approximately 6% of pregnant Arab Americans smoked during pregnancy. The prevalence of smoking behavior among pregnant ArabAmerican women was similar to that of smoking behaviors of Hispanics and Asian Americans in the United States. Cultural factors that support healthy behavior during pregnancy in the Arab culture seem to limit the use of tobacco in pregnant women. |

Nurses who care for Arab American pregnant women can use this information to better inform their care of patients. |

| 18. Rice &Kulwicki, 1992 | Interviews Self report survey |

Arab Americans Males and females N=237 Random sample |

To examine the prevalence and characteristics of cigarette smoking in a randomly selected sample of Detroit area Arab Americans. | 1. Statistical examination of smoking status bydemographic characteristics revealed group differences based on age, sex, and ethnicity. 2. Results indicate a current smoking rate of 38.9 percent, a former smoking rate of only 11.1 percent, a never smoking status of 50 percent, and a quit ratio of 22.2 percent. 3. No demographic differences were found for strength of habit, but length of smoking habit was positively related to age and level of education. |

This study shares the limitations of other studies of smoking behavior that rely solely on self-reports. Another concern is the disproportionately highernumber of women to men in the sample. |

| 19. Rice et al., 2003 | Four pilot studies: 3 descriptive and 1 pretest-post-test | Arab American adolescents N= 28; 9; 44; 119 | To determine the: 1. current tobacco use patterns and predictors among 14- to 18-year-old Arab-American youths; 2. psychometric properties of study measures (English and Arabic); 3. cultural appropriateness of Project Toward No Tobacco (TNT) for intervention; 4. Accessible population for a longitudinal study. |

1. Seven themes emerged from the data. 2. Pilot Intervention: a 37.5% cessation rate was found. 3. In the Pilot Clinic study, 24% males and 17% females smoked. 4. The current smokingrate in the Pilot School sample was 17%; 34% admitted to having ever smoked (even a puff). 4. Significant predictors for current tobacco use included poor grades, stress, having many family members and peers who smoke, being exposed to many hours of smoking each day, receiving offers of tobacco products, advertising and mail, and believing that tobacco can help one to make friends. | The four pilots contributed unique and essential knowledge for designing a longitudinal clinical trial on tobacco use by Arab American adolescents. |

| 20. Rice, 2005 | Intervention study Theory driven community-based program |

9th grade Arab American adolescents | 1. To examine cultural,personal, social, and environmental forces operating in Arab American youth who are at risk for becoming habitual tobacco users and to test the effects of a cessation intervention onsmoking behavior at 3, 6, and 12 months post-intervention. 2. To include testing a combined tailored prevention/cessation intervention (Project TNT-2) in Arab American 9th grade students as well as the teen clinicpatients. 3. To collect prevalence data from 9th–12th graders. |

9 Study measures weretranslated, back translated, and pilottested by using established procedures todetermine cross-cultural reliability andvalidity. | The abstracts and papers (all of which include some or many of the above factors) following this article were presented at the conference and provided data on Arab-American adolescenttobacco use thatwere collected over the past four years. In addition, these papers look at culturalsubgroups’ smoking behavior. |

| 21. Rice et al., 2006 | Cross-sectional survey | Arab American adolescents N= 1671 Convenience sample |

To evaluate a number of predictors (personal, psychosocial, sociocultural, and environmental) for tobacco use in Arab American adolescents. | 1. 29% of the youths reported ever cigarettesmoking. 2. Experimentation with narghile was 27%; it increased from 23% at 14 years to 40% at 18 years. 3. Ten predictors were found for ‘smoked a cigarette in past 30 days’ and nine and seven, respectively, for ‘ever smoked a cigaretteor narghile’. 4. Friends and family members smoking were the strongest predictors of cigarette smoking and ‘ever narghile use’. | A major limitation is the use of convenience sampling. It is not clear that this sample, although it is a very large one, is representative of the Arab American community from which it was drawn. Another concern was the uneven participation of the age groups |

| 22. Rice et al., 2007 | Cross-sectional survey study | Arab American and Non-Arab American Adolescent students N= 1455 |

To assess tobacco use and its predictors. | 1. Use of cigarettes by Arab American youth were 1%, 2% and 9%, respectively compared to 5%, 9% and 27%, respectively, for non-Arab youth. 2. In contrast, narghile use was 8%, 12%and 36% for regular, last 30 days, and experimental use, respectively, by Arab American 9th graders compared to 3%, 4% and 11%, respectively, for non- Arab youths. |

Further research is needed into this form of tobacco use that is spreading rapidly into the non-Arab community. Further exploration and direction for the development of community preventionand cessation programs in the very young. |

| 23. Rice et al., 2010 | Quasi-experimental design Non-equivalent three-group posttest design |

Adolescent smokers N= 380 Arab American& N= 236 non-Arab American |

To test a modified Project Towards No Tobacco (TNT) use program on cigarette smoking. | 1. Tenth graders given the intervention in the prior year reported a significantly lower rate of ever use at 23.3%. 2. Students who hadreceived the intervention were 1.43 times lesslikely to have smoked in the past 30 days. 3. The effect of theintervention on regular use was in the predicted direction, but thedifference was not significant. 4. The main effects for ethnicity were significant for cigarettes and water pipe smoking (ever, current, andregular). 5. Non-Arab students were 2 to 4 times more likely to engage in cigarette smoking than their Arab American counterparts. |

These findings provide support for a school-based intervention revised to focus on prevention as well as cessation and to be culturally consistent. There is need for further research and intervention tailoring to address the problem of water pipe smoking in a growing Arab American adolescent population. |

| 24. Templin et al., 2005 | Cross-sectional quantitative study |

High school students N= 2454 (1567 Arab Americans) |

1. To estimate the prevalence of different forms of tobacco use including narghile use (water pipe) in two suburban high school populations in an ethnically diverse, but predominantly Arabic, adolescent population. 2. To examine the relationships of cultural and behavioral variablesto reported adolescent tobacco use behavior. 3. To compare the ethnically diverse Michigan data to national data. |

The rates of cigarette smoking observed in Arab youth were not higher than those reported for non-Arabyouth, in fact, the rates were significantly lower. In contrast to cigarette use, narghile use was higher in Arab youth for each of the outcome categories, experimentation, social use, and addictive use. | The conclusions we present are tentativebecause additional data have yet to be analyzed. Another limitation is the self reporting bias. |

| 25. Weglicki et al., 2007 | Cross-sectional survey study | Adolescents N= 2782 (71% Arab American) Convenient sample |

To examine tobacco use, (ie, cigarette smoking and WPS in a sample of adolescents attending high school with a largeimmigrant Arab population. | 1. Cigarette smoking rates were significantly higher for non-Arab American youth for experimenting, current, and regular use 2. Cigarette smoking rates for non-Arab youth were lower than current national youth smoking rates but significantly higher than Arab American youth. 3. Rates for Arab American youth were much lower than current national reported data. 4. Rates of waterpipe smoking for U.S. youth, regardless of race or ethnicity, are not known. 5. Findings from this study indicate that both Arab American and non-Arab youth are experimenting and using waterpipe smoking regularly. 6. Grade, ethnicity, andsex were significantly related to waterpipe smoking. |

There are no known studies of waterpipe smoking rates for non-Arab US youth. These results underscore the importance of assessing novel forms of tobacco use, particularly waterpipe smoking, a growing phenomenon among U.S. youth |

| 26. Weglicki et al., 2008 | Cross-sectional survey study | High school students Males and females N= 1872 (70% Arab American) Convenience sample |

1. What are the tobacco use (cigarette and water pipe) patterns and percentages in Arab American and non-Arab American youth aged 14–18 years? 2. Which of the demographic and cultural factors of age,school grade, gender, and ethnic identity predict current cigarette and/or water-pipe smoking in Arab American andnon-Arab American youth? |

1. Arab American youth reported lower percentages of ever cigarette smoking, current cigarette smoking and regular cigarette smoking thannon-Arab American youth. 2. Arab American youth reported significantly higher percentages of ever waterpipe smoking and current waterpipe smoking than non-ArabAmerican youth. 3. 77% perceived waterpipe smoking to be as harmful as or more harmful than cigarette smoking. 3. Youth were 11 times more likely to be currently smoking cigarettes if they currently smoked water pipes. 4. Youth were also 11 times more likely to be current waterpipe smokers if they currently smoked cigarettes. |

A major limitation is the use of convenience sampling. A more equal distribution may have provided different smoking percentages and patterns by ethnicity, gender, and patterns of tobacco use Further research is needed to determine the percentages, patterns, and health risks of waterpipe smoking and its relationship to cigarette smoking among all youth. |

Table 1: Summary of studies on smoking behavior in arab americans, N=26.

Data synthesis

Smoking prevalence: Smoking prevalence among Arab Americans is high and ranges from 39% to 69%; rates are also higher in males than in females [10,11,43-45]. Rice et al. [11] conducted one of the earliest studies on Arab Americans and smoking. They surveyed 237 Arab Americans in Detroit, Michigan about their smoking behaviors. The majority of the sample were female (70%), Lebanese (75%), and born in the Middle East (97%), with an average stay in the US of 12.2 years. The authors found that 38.9% of the sample were current smokers, 11.1% were former smokers, and 50% had never been smokers; the majority of the current smokers were between the ages of 25 and 34 years, which was significantly different from the majority of former smokers who were older than 55 (p<0.002). In addition, Arab Americans in this sample had a higher smoking rate (38.9%) and a lower quitting rate (11.1%) compared to national data (28.9% smoking rate; 23% quitting rate) and State of Michigan data (29.2% smoking rate; 25.5% quitting rate).

In a cross-sectional study conducted in Richmond, Virginia [10], 69% of the 221 Arab American participants reported being current smokers. The authors defined current smokers as “having smoked at least one cigarette per day during the past 30 days” (p.787). In addition, men (67.6%) had higher rates of smoking than women (32.2%), and respondents who were born in Iraq or had parents who were born in Iraq had higher smoking rates than those who were born in other countries. Most of the participants (65.7%) grew up in homes with fathers who smoked cigarettes. Similarly, exclusive water-pipe smoking prevalence was high (44.2%) in this sample as well dual-smoking prevalence (e.g., smoking cigarettes and water-pipe) (55.8%) [42]. Similar to the reported prevalence of cigarette smoking, more male participants (66.6%) reported exclusive cigarette smoking than female participants (31.4%) while both groups reported experimenting with water-pipe smoking as young as 12 years of age.

In another study that examined smoking behaviors in 823 pregnant Arab American women who participated in the low-income nutritional supplemental program Women, Infants, and Children during the year 2002 in Michigan, 6% of the sample reported smoking while being pregnant [46]. The sample consisted of a majority of women between the ages of 20-29 (56.7%) with a high school education (50.5%). The reported low birth weight babies in the sample was 5.3%. Both rates of smoking prevalence during pregnancy (6%) and low birth weight babies (5.3%) in Arab American pregnant women were lower than Michigan state (29%; 7.4%) and national statistics (20%; 8.4%), respectively.

Smoking, both cigarettes and water pipe, has also been highly prevalent among Arab American adolescents. Few studies, however, have been conducted in the US to examine the prevalence of dual smoking and associated risk factors in this population. In a study evaluating tobacco use in Yemeni-American adolescents, researchers reported significant positive effects of age (p=0.03), parental smoking (p=0.01), peer smoking influence (p=0.001), and early age experimentation with tobacco (p=0.01) on tobacco use, and a significant negative effect of educational performance (p=0.04) on tobacco use [41,47]. In a sample of 297 Yemeni-American adolescents between the age of 14 and 18, 39% had tried tobacco and 17.2% were currently smoking water pipe. Water-pipe use was nine times as likely to be present among those who were experimenting with tobacco than among those who were not. Surprisingly, water-pipe smoking was not correlated with parental tobacco use [41]. Similarly, Islam et al. [48] performed a cross-sectional survey of 461 Muslim Arab American adolescents (12 to 19 years of age) in Virginia and were able to calculate the prevalence of susceptibility to smoking (50%), experimentation (e.g., having “ever” smoked) (45%), smoking in the last 30 days (18%), and current smoking (12%) in young adults. Males reported smoking experimentation at twice the rate as that reported by females. The authors also reported several significant risk factors associated with both susceptibility to smoking and experimentation with smoking such as peer pressure, perceived peer norms, and culturally based gender-specific norms (p<0.05). Religious influence and perceived negative consequences of smoking were significant protective factors in this sample (p<0.05). When susceptibility to smoking was analyzed by gender, religious influence was a protective factor for female participants (p=0.002) but not for male participants (p>0.05), and gender-specific norms were a risk factor for male participants (p=0.02) but not for female participants (p>0.05).

Weglicki et al. [49,50] conducted a study to compare cigarette and water-pipe smoking between Arab and non-Arab American youth. The sample consisted of 1872 students from Midwestern high schools; 70% of the samples were Arab Americans. Compared to non-Arab American adolescents, Arab Americans had significantly lower rates of cigarette smoking (ever and current) (20.1% and 6.9% versus 39.3% and 21.9%, respectively; p<0.01) but a significantly higher rate of water-pipe smoking (ever and current) (38% and 16.7% versus 21.3% and 11.3%, respectively; p<0.01). In addition, participants who reported family members smoking water pipes at home were 6.3 times more likely to be current water-pipe smokers.

El Hajj et al. [51] conducted the latest study in Colorado to examine tobacco use among Arab immigrants living in Colorado and the effect of some cultural predictors such as socioeconomic status on the smoking prevalence in this population as well as understanding the effect of acculturation on their tobacco use. The sample consisted of 100 adult Arab immigrants living in Colorado. The results showed that 19% of the participants were current cigarette smokers which is higher then the state average (16%) and 21% were current hookah smokers. When compared with the population in Colorado, Arab immigrants were twice as likely to use tobacco products. Participants in the sample who were more integrated into Arab culture were more likely to use tobacco products (p=0.03), to be current hookah smokers (p=0.008), to have family members who smoke cigarettes (p=0.02) and friends who use tobacco products (p=0.007). In addition, analysis showed that Arabic culture was the best predictor of family members who smoke cigarettes (R2=0.047) and of having friends who smoke hookah (R2=0.091).

Smoking cessation: Few researchers have addressed smoking cessation attempts among Arab Americans. Athamneh et al. [52] conducted a study in Houston, Texas to investigate the predictors of intention to quit water-pipe smoking among Arab American adults (n=340) and found that only 27% of the sample reported having the intention to quit. There was no significant relationship between the intention to quit water-pipe smoking and gender, income, marital status, or education. Several factors were associated with lower intentions to quit smoking; these included older age, cultural acceptability of water-pipe smoking, and perceptions of water-pipe smoking as less harmful than cigarette smoking. In another study, several barriers to smoking cessation and water-pipe use were reported among Arab Americans. El-Shahawy and Haddad [53] investigated the correlation between nicotine dependence and barriers to smoking cessation in a sample of 131 Arab Americans smokers living in Richmond, Virginia. The mean age for the sample was 28 and females comprised 28.6% of the sample. The authors found a significant difference in nicotine dependence between the exclusive cigarette smokers (Mean score for nicotine dependence=2.55) and the dualsmokers (cigarettes and water pipe; Mean score for nicotine dependence=3.71), who had a significantly higher nicotine dependence (p=0.006). Similarly, the barriers for smoking cessation such as “fear of failing to quit,” “thinking about never being able to smoke again,” “gaining weight,” or “no encouragement or help from friends,” were significantly higher for dual smokers compared to exclusive cigarettes smokers (Mean scores for barriers to cessation=45.21 vs. 38.47; p=0.005). In another study conducted in 2016, the authors [54] examined the effect of theory of planned behavior (TPB) constructs on the intention to quit water pipe smoking among 340 Arab Americans adults in Houston. The study sample consisted mainly of males (67%) and married (50%) with a mean age of 30 years. Out of the 340 Arab American water pipe smokers, only 27.43% (n=93) reported having an intention to quit. In the study, analysis showed that only half the constructs of the TPB were significantly associated with the intention to quit water pipe smoking; that is, behavioral evaluation and subjective norms.

To date, few interventions have been developed to facilitate smoking cessation in Arab Americans. We were able to identify one smoking cessation program in Arab American adolescents [12,55] and one in Arab American men [56]. The first study, which targeted Arab American adolescents, used an intervention titled the Project Toward No Tobacco Use (Project TNT), which was culturally-tailored in collaboration with ACCESS, the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services in Detroit, Michigan, which is home to the largest Arab American community in the US [12,55]. The Project TNT intervention has helped many Arab American adolescents stop smoking, and the results have been published in 7 articles [12,43,44,56-58] The intervention, which was composed of educational materials on smoking cessation, was tailored for youth through interactive power point presentations and video clips; the program was provided in both Arabic and English languages and featured Middle Eastern and non-Middle Eastern figures [53] Students who received the intervention reported a significantly lower rate of ever use of cigarette smoking after one year at 23.3% (Odds Ratio [OR]=1.31, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.64). Students who received the intervention were also 1.43 times (95% CI: 1.03, 2.01) more likely to abstain from smoking in the past 30 days than those who did not receive the intervention. In addition, the authors discussed that post-intervention, Arab American adolescents reported greater experimentation with water-pipe smoking than cigarettes (38% vs . 22%), and more current (16% vs. 6%) and regular (7% vs. 3%) use of water pipes than cigarettes, respectively. The water-pipe experimentation post-intervention probably occurred because the intervention targeted cigarette use only. Thus, future interventions in Arab American adolescents should target water-pipe smoking as well as cigarette smoking cessation.

The second intervention, which targeted Arab American adults, was conducted in Virginia and aimed at the development and pilot testing of a culturally-tailored and linguistically-sensitive Arabic-language smoking cessation program [57]. The intervention utilized the How to Quit Smoking in Arabic (HQSA) program and was comprised of 5 stages over a total of 12 weeks. Out of the 11 male participants who participated in the pilot study and completed all stages of the intervention, 8 reported that they were ready to stop smoking and 3 had stopped smoking by the three-month follow-up. Participants also provided feedback that helped in evaluating and revising the intervention to meet the cultural and linguistic needs of the Arab American population. Some of the feedback mentioned the use of a few colloquial terms that varied among different Arab nationalities, including the use of the word “In Sha’allah” (if God wills), as well as the difficulty in keeping up with a journal for daily activities, which is not part of Arab culture.

The two interventions demonstrated promising results for smoking cessation in Arab American populations. However, the results also highlighted the need for additional research and intervention studies to address the studies’ limitations. For example, the intervention targeting Arab American adults was a pilot study of 11 participants and was limited to males who were all recruited from one faith-based center. Data were collected based on self-report and no biological validation was used. Future studies should include diverse recruitment strategies, inclusion of Arab American women, and biological measures to validate the results of smoking cessation interventions.

Acculturation and smoking: Acculturation, which is the continuous process of interaction between different cultures, can influence healthrelated behaviors such as smoking, especially over time [9,16,30,36]. Although measuring the degree of acculturation is complex, researchers have either used validated instruments that can capture aspects of the acculturation process, or proxy indicators such as length of stay in the country or the language spoken at home. For example, one study used three proxy indicators for acculturation (language spoken at home, number of years in the US, first language learned) and found that the number of years spent in the US and the age when an individual moved to the US were positively correlated with the number of smoked cigarettes per day (F=3.4, p<0.00). Similarly, these factors were negatively correlated with the number of attempts to quit smoking (OR=0.93, CI: 0.87, 0.98; and OR=0.93, CI: 0.88, 0.98 respectively) [10].

In another cross-sectional study [58], 96 Arab American smokers (71%) and ex-smokers (29%) were recruited from the Midwest area; the sample consisted of mostly men (81.3%) who had lived in the US for five years or more (62%) and were approximately 35 years of age. The findings revealed a significant positive correlation between acculturation and tobacco dependence as well as between tobacco exposure and tobacco dependence [59,60]. Acculturation was measured using the Male Arab American Acculturation scale that has four subscales (separation, assimilation, integration, and marginalization). There was a positive significant correlation between separation versus assimilation and nicotine dependence (r=0.18, p<0.05) but no significant relationship between integration and marginalization and nicotine dependence. Indeed, Arab Americans who behaved like and spent the most time with their ethnic peers were more dependent on nicotine.

Health beliefs and smoking: Individuals’ health beliefs that are related to their susceptibility to or severity of a disease, as well as their beliefs of the barriers and benefits of certain health behaviors, strongly influence health behaviors such as smoking [61] In a study by Haddad et al. [10], 59.3% of respondents who were asked about general harmful effects of smoking stated that it had no harmful effects; in addition, fewer than 33% of respondents were concerned about the negative effects of smoking on their health. Prestige and social acceptance in the new culture were the most frequently reported reasons for smoking. Of the 69 participants who were non-smokers, only 7 reported that the harmful effects of smoking were good reasons to avoid the habit. None of the studies found and included in this review applied a model such as the Health Belief Model, which is an effective tool in examining smoking behavior and barriers to cessation in Arab Americans.

Sociocultural factors and smoking: In addition to health beliefs, sociocultural factors play a key role in the smoking behavior of adolescents. In a qualitative study that explored opinions about tobacco use and cessation programs among 28 Arab American adolescents, the authors [58] reported that being cool, hanging out with friends, easy accessibility to cigarettes, and feeling good after smoking were the reasons adolescents chose to smoke. Additionally, one of the main barriers to smoking cessation was having friends who smoke. Despite awareness of the dangers of smoking, the adolescents were mainly concerned with the present effects of smoking on their health, such as the possibility that their growth might be stunted or that they would be unable to play sports. In another study, Kassem et al. [61] examined the initiation, and pros and cons of hookah use in a sample of 458 adult Arab Americans (mean age: 28.4 years). Results showed that 41.2% of the participants first tried hookah smoking at an age younger than 18 years, and the majority were with friends when they first tried hookah smoking. However, early hookah initiators were 1.9 times more likely than late hookah initiators to be with family when first tried hookah (p=0.004). A total of 61.2% of participants were ‘ever dual smokers’ while 31% were ‘current dual smokers’ and men were more likely than women to be current dual smokers (p=0.035). Participants mainly enjoyed the flavors of hookah tobacco, and their major complaints were coughing, dizziness, and headaches.

Discussion

The reviewed studies in this systematic review showed that smoking, both cigarettes and water pipe, is highly prevalent among Arab Americans. Investigating the acculturation process among immigrants has been an increasingly important topic in multicultural research and in understanding the health outcomes of the immigrant populations in the US. Acculturation has been linked to health behaviors and health outcomes among immigrants [9,30,36]. According to the research, Arab Americans have high rates of smoking and low rates of smoking cessation [11,60]. In addition, because they are ethnic minority immigrants, they are vulnerable to a range of health disparities, such as high rates of smoking, obesity, and low rates of yearly regular checkups, which can negatively affect their health outcomes in the long-term. Strong evidence is available to support the existence of health disparities among ethnic minorities in the US and its impact on their health outcomes [61,62]. These disparities are related to several intersecting factors including the language barrier, lack of resources, education, acculturation, poverty, immigrant status, lack of health insurance, discrimination, and cultural and religious factors [63]. In addition, Arab Americans are a very heterogeneous group from diverse socio-economic backgrounds and can be found in all fifty states across the US. The reviewed studies were mostly conducted in the Midwest near Michigan and in Virginia. The findings of these studies do not adequately represent Arabs in the US. Michigan, for example, has one of the highest populations of Arabs in the US; however, this population represents a disproportionate amount of lower-income Arab Americans compared to other Arab Americans living in different states [64].

Despite the increasing numbers of Arab Americans in the US and their high rate of smoking prevalence, findings of this systematic review reveal that limited research has been conducted on smoking behavior in Arab Americans. Of the studies that exist, the majority focused on smoking prevalence, smoking cessation, acculturation, and health beliefs in Arab Americans adolescents. To date, only two smoking cessation programs have been developed for Arab Americans, despite the high prevalence of both cigarette and water-pipe smoking in this community. The review also demonstrated that there have been no studies conducted in the US investigating the relationship between acculturation, smoking behavior, and cancer in Arab Americans.

Gender and religion are other important factors that need to be addressed in Arab American studies. Most studies reviewed showed that males had higher smoking rates than females for both cigarette and water-pipe smoking. A study examining Muslim US students also reported that males were twice as likely to be lifetime water-pipe smokers than females [65]. Male dominance, gender roles and norms, and patriarchy in Arab societies can be interpreted as some of the reasons for gender differences in smoking; however, more studies that specifically investigate these gender differences are needed, while controlling for other socio-demographic variables. In the reviewed studies, religion, religiosity, and their impact on daily life and health behaviors, specifically smoking, have not been addressed. Despite the fact that Arabs in the Arab world are mostly Muslims, Arabs in the US are mostly Christians [66]. In addition, cultural traditions and religion are very entangled among Arabs, thus making it difficult to differentiate whether a specific behavior is supported by the culture or the religion. For example, fatalism and total reliance on God’s will are common beliefs of both Muslim and non-Muslim Arabs [67], making these important factors influencing certain health beliefs and behaviors such as smoking and its association with cancer. Therefore, religion and religiosity are also important to address in future studies investigating smoking and smoking cessation in Arab Americans.

This systematic review signifies the need for future studies focusing on determining the health beliefs and sociocultural factors that influence smoking prevalence in Arab Americans, and the effect of acculturation on smoking rates over time in order to develop culturally appropriate smoking cessation interventions for this population. In addition, future research needs to address the limitations of present studies by including female participants, expanding recruitment strategies, examining a broader range of geographical areas, and conducting additional research on water-pipe smoking. In this way, researchers in health promotion can develop interventions to reduce the high rates of smoking among Arab Americans as well as prevent diseases such as cancer, stroke, heart disease, and diabetes in both primary smokers and their family members, who are exposed to second hand smoke. A limitation for this review, only articles published in English were included. This may have created some bias concerning the conclusions (i.e, a language bias). Non off the reviewed studies used randomized control design, also most of the studies used a convenient sample which limit generalizability.

Conclusion

Evidence clearly exists that establishes a connection between high smoking rates and health disparities. To our knowledge we are the first to review Arab American smoking behavior. This systematic review provides a description of Arab Americans’ smoking behavior, specifically focusing on the relationship between this behavior and the acculturation level and health beliefs in this population. Findings demonstrated the scarcity of research on smoking in Arab Americans. This knowledge gap has impeded the development of interventions that aim to improve health outcomes and reduce health disparities in this vulnerable, ethnic minority population. Given the rapid increase of Arab American residents in the US, more research about the smoking behavior, use, and cessation attempts of this population is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Debra McDonald from the University of Florida College of Nursing for editing the final manuscript.

References

- Bullen C (2008) Impact of tobacco smoking and smoking cessation on cardiovascular risk and disease. Expert Rev of CardiovascTher 6: 883-895.

- Gandini S, Botteri E, Iodice S, Boniol M, Lowenfels AB, et al. (2008) Tobacco smoking and cancer: A meta analysis. Int J Cancer 122: 155-164.

- Gritz ER, Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, Mehta NV, et al. (2006) Successes and failures of the teachable moment. smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer 106: 17-27.

- Salim EI, Jazieh AR, Moore MA (2011) Lung cancer incidence in the Arab league countries: Risk factors and control. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 12: 17-34.

- Twombly R (2005) Cancer surpasses heart disease as leading cause of death for all but the very elderly. J Natl Cancer Inst 97: 330-331.

- World Health Organization (2013) World health report 2013: Research for universal health coverage.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) Adult cigarette smoking in the United States: Current estimate.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2001) Tobacco use among specific populations.

- Forzley M (2005) Advancing the health of Arab Americans: Key points to obtaining resources and establishing programs focused on special populations. Ethn Dis 15: 190-92.

- Haddad L, El-Shahawy O, Shishani K, Madanat H, Alzyoud S (2012) Cigarette use attitudes and effects of acculturation among immigrants in USA: A preliminary study. Health 4: 785-793.

- Rice VH, Kulwicki A (1992) Cigarette use among Arab Americans in the Detroit metropolitan area. Public Health Rep 107: 589-594.

- Rice VH, Templin T, Kulwicki A (2003) Arab-American adolescent tobacco use: Four pilot studies. Prev Med 37: 492-498.

- Berry JW (2005) Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. Int J IntercultRelat 29: 697-712.

- Berry JW (2001) A psychology of immigration. J SocIss 57: 615-631.

- Castro VS (2003) Acculturation and psychological adaptation. Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Jadalla A, Lee J (2012) The relationship between acculturation and general health of Arab Americans. J TranscultNurs 23: 159-165.

- Taylor SAJ (2015) Culture and behaviour in mass health interventions: Lessons from th e global polio eradication initiative. Crit Public Health 25: 192-204.

- Arab American Institute (2015) Arab American demographics.

- Kayyali RA (2006) The Arab Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Ibish H (2001) 1998-2000 report on hate crimes and discrimination against Arab Americans. American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee.

- Naber N (2000) Ambiguous insiders: An investigation of Arab American invisibility. Ethn Racial Stud 23: 37-61.

- Barry DT (2005) Measuring acculturation among male Arab immigrants in the United States: An exploratory study. J Immigr Health 7: 179-184.

- Jamal A, Naber N (2008) Race and Arab Americans before and after 9/11. (1st edn), Syracuse University Press, New York.

- Naber N (2006) Arab American femininities: Beyond Arab virgin/ American(ized) whore. Feminist Stud 32: 87-111.

- Abboud S, Jemmott LS, Sommers MS (2015) “We are Arabs:” The embodiment of virginity through Arab and Arab American women’s lived experiences. Sex Cult 19: 715-736.

- Institute of Medicine (2012) How far have we come in reducing health disparities? Progress since 2000: Workshop summary. National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- Abraido-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Florez KR (2005) Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation?: Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. SocSci Med 61: 1243-1255.

- Choi S, Rankin S, Stewart A, Oka R (2008) Effects of acculturation on smoking behavior in Asian Americans: A meta-analysis. J CardiovascNurs 23: 67-73.

- Guthrie BJ, Young AM, Williams DR, Boyd CJ, Kintner EK (2002) African American girls’ smoking habits and day-to-day experiences with racial discrimination. Nurs Res 51: 183-190.

- Klonoff EA, Landrine H (1996) Acculturation and cigarette smoking among African American adults. J Behav Med 19: 501-514.

- Zhang J, Wang Z (2008) Factors associated with smoking in Asian American adults: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 10: 791-801.

- Arcia E, Skinner M, Bailey D, Correa V (2001) Models of acculturation and health behaviors among Latino immigrants to the US. SocSci Med 53: 41-53.

- Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B (2004) Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. SocSci Med 59: 973-986.

- Klonoff EA, Landrine H (1999) Acculturation and cigarette smoking among African Americans: Replication and implications for prevention and cessation programs. J Behav Med 22: 195-204.

- Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L (2009) Defining and measuring acculturation: A systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. SocSci Med 69: 983-991.

- Smyth NJ (2004) Introduction. J Hum BehavSoc Environ 7: 1-4.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009)Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151: 264-269.

- Baker OG, Rice V (2008) Predictors of narghile (water-pipe) smoking in a sample of American Arab Yemeni adolescents. J TranscultNurs 19: 24-32.

- Haddad L, El-Shahawy O, Ghadban R, Barnett TE, Johnson E (2015) Waterpipe smoking and regulation in the United States: A comprehensive review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12: 6115-6135.

- Templin T, Rice V, Gadelrab H, Weglicki L, Hammad A, et al. (2005) Trends in tobacco use among Arab/Arab-American adolescents: Preliminary findings. Ethn Dis 15: 65-68.

- Rice VH, Weglicki LS, Templin T, Hammad A, Jamil H, et al. (2006) Predictors of Arab American adolescent tobacco use. Merrill Palmer Q (Wayne State Univ Press). 52: 327-342.

- Islam SM, Johnson CA (2003) Correlates of smoking behavior among Muslim Arab-American adolescents. Ethn Health 8: 319-337.

- Alzyoud S, Haddad L, El Shahawy O, Ghadban R, Kheirallah K, et al. (2014) Patterns of waterpipe use among Arab immigrants in the USA: A pilot study. Br J Med Med Research 4: 816-827.

- Kulwicki A, Smiley K, Devine S (2007) Smoking behavior in pregnant Arab Americans. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 32: 363-367.

- Baker O (2005) Relationship of parental tobacco use, peer influence, self-esteem, and tobacco use among Yemeni-American adolescents: Mid-range theory testing. Ethnic Dis 15: 69-71.

- Weglicki LS, Templin TN, Rice VH, Jamil H, Hammad A (2008) Comparison of cigarette and water-pipe smoking by Arab and Non–Arab-American youth. Am J Prev Med 35: 334-339.

- Weglicki LS, Templin T, Hammad A, Jamil H, Abou-Mediene S, et al. (2007) Tobacco use patterns among high school students: Do Arab American youth differ? Ethnic Dis 17: 22-24.

- El Hajj, Cook PF, Magilvy K, Galbraith ME, Gilbert L, et al. (2015) Tobacco Use Among Arab Immigrants Living in Colorado Prevalence and Cultural Predictors. J TranscultNurs.

- Athamneh L, Sansgiry SS, Essien EJ, Abughosh S (2015) Predictors of intention to quit waterpipe smoking: A survey of Arab Americans in Houston, Texas. J Addict.

- El-Shahawy O, Haddad L (2015) Correlation between nicotine dependence and barriers to cessation between exclusive cigarette smokers and dual (water pipe) smokers among Arab Americans. Subst Abuse Rehabil 6: 25-32.

- Athamneh L, Essien EJ, Sansgiry SS, Abughosh S (2015) Intention to quit water pipe smoking among Arab Americans: Application of the theory of planned behavior. Jethnicity in substance abuse pp: 1-11.

- Rice VH, Weglicki LS, Templin T, Jamil H, Hammad A (2010) Intervention effects on tobacco use in Arab and non-Arab American adolescents. Addict Behav 35: 46-48.

- Haddad L, Corcoran J (2013) Culturally tailored smoking cessation for Arab American male smokers in community settings: A pilot study. Tob Use Insights 6: 17-23.

- Kulwicki A, Hill Rice V (2003) Arab American adolescent perceptions and experiences with smoking. Public Health Nurs 20: 177-183.

- Rice VH (2005) Arab-American youth tobacco program. Ethn Dis 15: 54-56.

- Al-Faouri I, Weglicki L, Rice VH, Kulwicki A, Jamil H, et al. (2005) Culturally sensitive smoking cessation intervention program redesign for Arab-American youth. Ethn Dis 15: 62-64.

- Al-Omari H, Scheibmeir M (2009) Arab Americans' acculturation and tobacco smoking. J TranscultNurs 20: 227-233.

- Kassem, Jackson SR, Daffa RM, Liles S, Hovell MF (2015) Arab-American hookah smokers: initiation, and pros and cons of hookah use. Am j health behavior 39: 680-697.

- Champion VL, Skinner CS (2008) The health belief model. (4th edn), John Wiley & Sons, San Francisco, pp:45-65.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) Cigarette smoking in the United States, 2011.

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S (2012) More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. SocSci Med 75: 2099-2106.

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA (2009) Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 32: 20-47.

- Çiftçi A, Reid-Marks L, Shawahin L (2014) Health disparities and immigrants.. Santa Barbara, Praeger, CA, pp: 51-71.

- Read JG, Amick B, Donato KM (2005) Arab immigrants: A new case for ethnicity and health? SocSci Med 61: 77-82.

- Arfken CL, Abu-Ras W, Ahmed S (2015) Pilot study of waterpipe tobacco smoking among US Muslim college students. J Relig Health 54: 1543-1554.

- Arab American National Museum (2015) Arab Americans: An integral part of American society. Arab American National Museum Educational Series.

- Shah SM, Ayash C, Pharaon NA, Gany FM(2008) Arab American immigrants in New York: Health care and cancer knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. J Immigr Minor Health 10: 429-436.

--

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 19991

- [From(publication date):

August-2016 - Nov 21, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 19190

- PDF downloads : 801