Simultaneous Fractionated Cisplatin and Radiation Therapy in the Treatment of Advanced Operable Stage III and IV Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity and Pharynx

Received: 26-Sep-2015 / Accepted Date: 27-Oct-2015 / Published Date: 04-Nov-2015 DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000215

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate simultaneous fractionated cisplatin and radiation therapy in the treatment of advanced operable Stage III and IV squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and pharynx.

Methods: A retrospective chart review of a database with Stage III and IV squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and pharynx patients was conducted. A total of 105 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and pharynx underwent chemoradiotherapy treatment of two types: CTRT consisted of pre-operative cisplatin, 20 mg/m2 intravenously for 4 consecutive days during weeks 1, 4, and 7 of radiotherapy; control chemotherapy consisted of several regimens: cisplatin, 75 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 22, and 43 of radiotherapy; carboplatin, 100 mg/m2 and taxol, 45 mg/m2 once per week during radiotherapy; or CTRT regimen following surgery. Toxicity to treatment, clinical response, biopsy result, incidence or recurrence, surgery, overall and disease-free survival were measured.

Results: A total of 91 patients underwent CTRT and 14 patients underwent control. Overall, CTRT experienced less high-grade toxicity (14% vs 50%, P<0.05). CTRT had trends of higher clinical complete response (73% vs 57%) and higher incidence of histologic complete response as evidenced by negative biopsy (67% vs 57%). Among patients who had post-treatment surgery, 48% of CTRT surgeries were radical compared to 100% of control surgeries (P=0.07). CTRT had less distant metastasis compared to control (7% vs 50%, P=0.06). Regarding expiratory status, CTRT had less death with disease (56% vs 75%, P=0.33). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a trend toward increased long-term survival among CTRT compared to control.

Conclusion: Overall, CTRT experienced significantly less toxicity. CTRT showed trends toward higher clinical complete response and histologic complete response compared to control. CTRT also had trends toward less distant metastases and less death with disease compared to control.

Keywords: Squamous cell carcinoma, Head and neck, Cisplatin, Radiotherapy

251178Introduction

Squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck (SCCHN) make up approximately 3 percent of all cancer cases in the United States [1]. SCCHN are most common in the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. These cancers are curable when detected at an early stage, but most patients present with locally advanced Stage III or IV disease [2]. Traditional treatment for such cancers has involved radical surgery and/or post-operative radiotherapy [3]. More recently, multi-modality therapies have become useful for improving locoregional control and organ preservation, although survival is still poor [2]. Multi-modality therapies involve a combination of surgery, nontraditional radiation therapy, and chemotherapy integration. However, the roles of each technique are not yet standardized.

While no single treatment regimen has been defined as most effective in treating SCCHN, several studies have identified certain multi-modality combinations that produce greater success in terms of organ preservation, survival, locoregional control, and toxicity to treatment. Common multi-modality treatments include docetaxel plus cisplatin followed by fluorouracil infusion for 4 days every 3 weeks; high-dose cisplatin given on days 1, 22, and 43 of radiotherapy; daily low-dose concomitant cisplatin; and a weekly combination of carboplatin and taxol [2,4-6]. These regimens are just a sample of the variety of SCCHN treatments that have been attempted. Many other combinations of radiotherapy and chemotherapy exist. Thus, it is difficult to determine which treatment is best for the patients.

In recent years, investigators have found that concurrent chemotherapy and radiation prior to surgery show synergistic effects in tumor treatment, improving overall disease control and survival [3]. Organ preservation, which is highly valued by most patients, is also improved due to less post-chemoradiotherapy surgery. Several pilot investigations have suggested that low-dose, fractionated cisplatin administered simultaneously with concomitant high-dose radiotherapy may be effective in curing cancer while preserving head and neck function [7-9]. The objective of the present study was to evaluate patients with advanced operable Stage III and IV SCCHN who were treated pre-operatively with 20 mg/m2 IV cisplatin given on 4 consecutive days every 3 weeks during high-dose irradiation therapy (CTRT).

Methods

With the approval of the Inspira Health Network Institutional Review Board, medical records of 91 patients with Stage III and IV squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and/or pharynx who received CTRT were reviewed retrospectively and compared with an unselected control group of 14 patients who underwent other accepted standard, medical and surgical treatment regimens, and received at least part of their care at the Inspira health Network, Vineland, NJ. CTRT chemotherapy consisted of pre-operative cisplatin, 20 mg/m2 intravenously for 4 consecutive days during weeks 1, 4, and 7 of radiotherapy. CTRT patients were included in the outcomes evaluation, on an intent-to-treat basis, if they had at least one course of concomitant chemotherapy during radiation therapy. All control patients completed the cancer treatment regimen prescribed for each. The Southern New Jersey Head and Neck Treatment Network is a group of medical oncologists and radiation oncologists who have treated patients of the senior author (GJS) with CTRT, based on the successes of previously published pilot trials of this regimen and their positive clinical experiences with it. Conversely, control chemotherapy consisted of several regimens: cisplatin, 75 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 22, and 43 of radiotherapy; carboplatin, 100 mg/m2 and taxol, 45 mg/m2 once per week during radiotherapy; or CTRT regimen following surgery. The treatment regimens of control patients are described in Table 1, including the drug regimen, surgery, and location of treatment. Both the CTRT and control groups were treated between June 1992 and October 2011. Determination of whether patients received CTRT or control regimens was at the discretion of the treating physician. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the definition of need for surgery was not controlled. However, all operations at all institutions were performed by trained head and neck surgical oncologists.

Over the course of the study, the radiation therapy technique varied as the technology changed. In the earlier portion of the study, patients were treated with a regimen consisting of single daily fractionation with 6 MV photons and 3D treatment planning followed by a boost, in which they were treated with a hyperfractionated (two fractions/day) regimen with concurrent chemotherapy. In 2006, patients were treated with normal fractionation to a higher total dose, between 70-74 Gy. In the latter part of the treatment study, the patients were treated with a field-within-a-field technique utilizing head and neck IMRT. PTVs were treated between 70-74 Gy. Most treatment regimens were delivered with 6 MV photons with either customized blocks or multileaf collimator generated blocks. Verification was performed using port films and later changed to stereoscopic imaging followed by cone beam CT.

The study variables included age, sex, race, vital status, alcohol use, tobacco use, tumor site, tumor grade, clinical stage, surgery, chemoradiotherapy regimen, clinical response, post-CTRT biopsy result, recurrence, and toxicity to treatment. Clinical stage was determined according to the classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging [10]. Post-chemoradiotherapy biopsy determined whether or not patients whose cancers regressed completely clinically (Clinical Complete Response – CCR) had achieved either a histologically complete response (HCR) or still had residual tumor. Patients with residual disease were recommended for curative surgery. Toxicity to treatment was determined according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [11].

Statistical analysis was performed using the chi-squared equation for categorical variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare age. Overall survival and disease-specific survival were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier logarithmic rank test. Median follow-up was 20 months, with a range of 1 to 128 months. The level of significance was set as p<0.05 (SAS/STAT(R) 9.22 User’s Guide).

| Patient Characteristics | CTRT (SD)A n=91 | CONTROL (SD)B n=14 |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.4 (12.7) | 58.1 (9.6) | 0.717 |

| Sex (male/female) | 70/21 | 10/4 | 0.655 |

| Race (white/other) | 65/26 | 11/3 | 0.578 |

| Alcohol use | 54 | 9 | 0.729 |

| Tobacco use | 71 | 13 | 0.196 |

| Tumor site (oral cavity/pharynx) | 65/28 | 11/3 | 0.502 |

| Tumor stage (III/IV) | 18/73 | 1/13 | 0.252 |

| Tumor grade (I/II/III) | 10/45/13 | 1/4/5 | 0.617 |

| A: CTRT treatment consisted of pre-operative cisplatin, 20 mg/m2intravenously for 4 consecutive days during weeks 1, 4, and 7 of radiotherapy. B: CONTROL treatment consisted of several regimens: cisplatin, 75 mg/m2intravenously on days 1, 22, and 43 of radiotherapy; carboplatin, 100 mg/m2and taxol, 45 mg/m2once per week during radiotherapy; or CTRT regimen following surgery. |

|||

Table 1: Clinical Characteristics of 105 Patients Who Received Treatment for Stage III and IV Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity and Pharynx Between June 1992 and October.

Results

Patient demographics and tumor characteristics for CTRT and control are displayed in Table 1. Of the 105 patients evaluated in this study, 75 had squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and 30 of the pharynx. No significant differences between CTRT and control regarding age, sex, race, alcohol/tobacco use, tumor site, clinical stage, or tumor grade were found. In the CTRT group, 30 patients (33%) had N0 disease, compared to 5 (36%) patients in the control group. The remaining patients had nodal disease: CTRT had 10 (11%) N1 tumors, 26 (29%) N2 tumors, and 25 (28%) N3 tumors; control had 3 (21%) N1 tumors, 3 (21%) N2 tumors, and 3 (21%) N3 tumors. The CTRT patient group had 80% Stage IV carcinoma (73/91) compared to 93% (13/14) in the control group. Primary CTRT tumors were 1 unknown (1.5%), 1 (1.5%) T1, 19 (21%) T2, and 29 (32%) T3, and 41 (45%) T4. Among control primary tumors there were no unknown or T1, 3 (21%) T2, and 6 (43%) T3, and 5 (36%) T4. No patient in this study had distant metastases at the time of primary treatment. No significant differences were found for tumor stage or TNM.

Toxicity from chemotherapy and radiation therapy is displayed in Table 2. Acute morbidity in CTRT included grade III dehydration, bleeding, and/or hospitalization in 12 (13%) patients and grade IV dehydration in 1 (1%) patient. No CTRT patients had grade V toxicity. In control, morbidity included 5 (33%) patients with grade III toxicity, 1 patient (7%) with grade IV clotting, and 1 (7%) patient with grade V hypoxemia. No toxicity was noted in 38% (35) of CTRT patients and in 0% of control patients (P<0.01). High-grade toxicity (grade 3-5) was significantly increased in control compared to CTRT (50% versus 14%; P<0.05). Three CTRT patients did not complete all cycles of chemotherapy. All control patients completed their prescribed cancer treatment. Although the specific application of radiation therapy evolved during the years in which CTRT patients were treated from daily fractionation to IMRT, toxicity and rates of CCR and HCR did not vary throughout the study.

| Toxicity Grade | CTRT n=91 | CONTROL n=13A | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No toxicity 0 |

35 (38%) | 0-Jan | 35 | P<0.01 |

| Low gradetoxicity 1 |

21 (23%) | 2 (15%) | 23 | |

| 2 | 22 (24%) | 4 (31%) | 26 | P=0.475 |

| High grade toxicity 3 |

12 (13%) | 5 (38%) | 17 | |

| 4 | 1 (1%) | 1 (8%) | 2 | P=0.130 |

| 5 | 0 | 1 (8%) | 1 | |

| Total | 91 | 13 | 104 | P<0.05 |

| A: 1 Control patient was unavailable for toxicity determination | ||||

Table 2: Toxicity to chemotherapy/radiation therapy (determined by the NCI common terminology criteria for adverse events).

Response to pre-operative treatment is listed in Table 3. A clinically complete response was seen in 73% (66/91) of CTRT patients versus 57% (8/14) in control (P=0.240). Post-chemoradiotherapy biopsy revealed a histologically complete response in 61 out of 91 CTRT patients (67%) and in 8 out of 14 control patients (57%) (P=0.467).

| Treatment Response | CTRT n=91 |

CONTROL n=14 |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Response | |||

| Clinically Complete Response | 66 (73%) | 8 (57%) | |

| Partial Response | 25 (27%) | 6 (43%) | P=0.240 |

| Biopsy Result | |||

| Histologically Complete Response | 61 (68%) | 8 (57%) | |

| Residual Disease | 30 (33%) | 6 (43%) | P=0.467 |

| Type of Surgery | |||

| Radical Surgery | 12 (13%) | 4 (29%) | |

| Neck Dissection Only | 11 (12%) | 0 | P=0.072 |

Table 3: Response to pre-operative treatment.

Curative cancer surgery results are seen in Table 3. CTRT and control did not differ in the number of patients who required curative surgery (23/91 versus 4/14; P=0.7913). However, 11 of the CTRT patients had neck dissection only (48% of surgeries) and 12 (52%) had composite resection of the primary tumors with neck dissection and reconstruction. In Control, all 4 (100%) operations were radical composite resections. Thus, organ preservation was achieved in 79/91 (87%) of CTRT, but in only 10/14 (71%) of control patients (P=0.136).

Cancer recurrence and survival data are tabulated in Table 4. Median follow-up time was 20 months, with a range from 1 to 128 months. Recurrences developed in 29 out of 91 (32%) CTRT, and in 6 out of 14 (43%) control (P=0.417). The control group had 14% distant metastases, whereas CTRT had 2% distant metastases (P<0.05). Regarding overall survival, 59 out of 91 CTRT patients are still alive, while 6 out of 14 control patients are alive (65% versus 43%; P=0.115). Overall, 21% of CTRT patients died with disease compared to 50% of control patients (P<0.05).

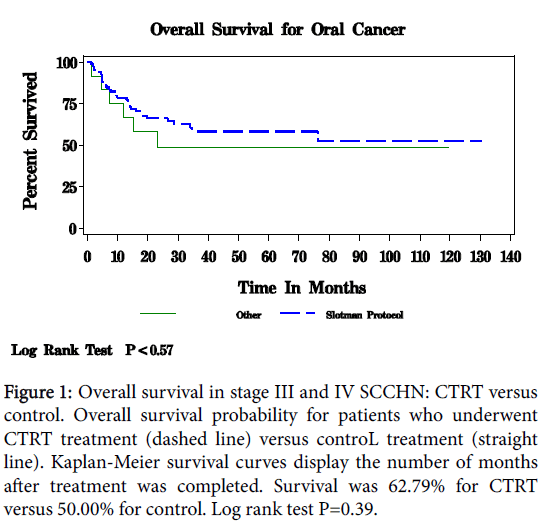

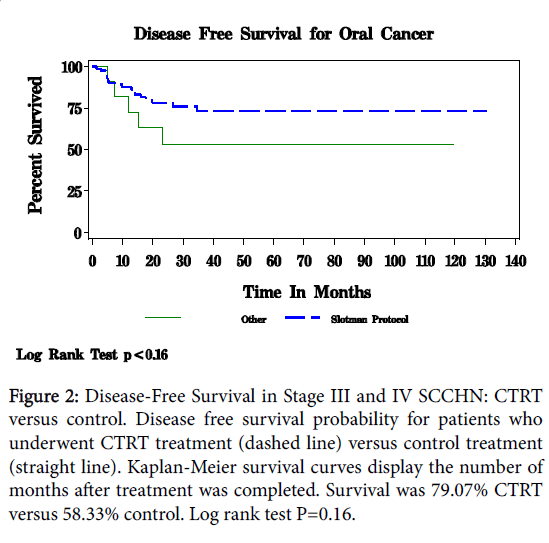

Figure 1 displays the overall Kaplan-Meier survival for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and pharynx. With a median follow-up of 20 months, survival overall was 62.79% for CTRT and 50.00% in the control group (P<0.57). Disease-free survival is depicted in Figure 2. For CTRT, disease-free survival was 79.07% for CTRT versus 58.33% in control patients (P<0.16).

| Patient Characteristics | CTRT n=91 |

CONTROL n=14 |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dead | |||

| Died with disease | 18 (20%) | 6 (43%) | |

| Died disease-free | 8 (9%) | 0-Jan | P=0.117 |

| Recurrence | |||

| Local | 27 (30%) | 4 (29%) | |

| Distant | 2 (2%) | 2 (14%) | P=0.064 |

Table 4: Overall survival, end of life status and recurrence data.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the simultaneous administration of low-dose fractionated cisplatin chemotherapy and high-dose irradiation (CTRT) may be an effective primary treatment for patients with advanced operable Stage III and IV SCCHN of the oral cavity and pharynx. Toxicity to treatment was significantly lower with CTRT compared with control and with other standard regimens reported in the literature. Biopsy revealed a trend of more histologic complete responses in CTRT compared to control. No differences were found regarding curative surgery; however, organ preservation was achieved in a higher percentage of CTRT patients. CTRT had fewer distant metastases versus control. Furthermore, patients who underwent CTRT remained disease-free and expired of other causes more frequently than did the control group. Lastly, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicate a trend toward better disease-free survival among CTRT patients. Our review of the literature indicates that these treatment effects of CTRT on Stage III and IV SCCHN compared with other cancer protocols have not been reported previously and are significant findings of this study.

While clinical adverse events were common among control patients who underwent other treatment regimens for SCCHN, CTRT toxicity was minimal. Only 13% of CTRT patients suffered grade 3 toxicity, 1 patient had grade 4 toxicity, and no patients experienced grade 5 toxicity. In addition, 38% of CTRT patients completed treatment with no toxicity at all. Previously published clinical trials of concomitant chemoradiotherapy almost universally have reported increased toxicities due to the potency of the drug combinations [3]. In their evaluation of high-dose 100 mg/m2 cisplatin on days 2, 16, and 30 of radiotherapy plus 5-FU, Bourhis et al. observed grade 3 and higher toxicity in 83% of their patients [12]. Unfortunately, these very high rates of toxicity also are common among studies of high-dose cisplatin given every three weeks [4,13]. Alternatively, a study with weekly lowdose cisplatin (30 mg/m2) during radiotherapy still observed grade 3 to 4 mucositis in 35.2% [14]. In contrast, an early pilot investigation of the regimen that became CTRT (20 mg/m2 cisplatin on day 1 to 4 and 22 to 25 of radiotherapy) reported only 27% grade 3 toxicity and no grade 4 or 5 toxicity, similar to the present results [9]. The results of the present study suggest that chemoradiotherapy protocols in treating SCCHN need to move in the direction of low-dose chemotherapy in fractionated administrations so as to improve patient tolerance of preoperative treatment without compromising therapeutic effectiveness.

Figure 1: Overall survival in stage III and IV SCCHN: CTRT versus control. Overall survival probability for patients who underwent CTRT treatment (dashed line) versus controL treatment (straight line). Kaplan-Meier survival curves display the number of months after treatment was completed. Survival was 62.79% for CTRT versus 50.00% for control. Log rank test P=0.39.

In addition to significantly reducing toxicity, the CTRT chemoradiotherapy combination analyzed in this study resulted in highly effective treatment effects against the cancers. Our complete response rate (CCR) was 73%, and our negative biopsy (as indicated by a histologically complete response (HCR)) was 67%. These outcomes are favorable to those of Paccagnella et al., who treated SCCHN patients with either two cycles of cisplatin 20 mg/m2, days 1-4, plus 5- FU 800 mg/m2/day during weeks 1 and 6 of radiotherapy or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 plus cisplatin 80 mg/ M2, day 1, and 5-FU 800 mg/m2/day every 3 weeks [15]. The two arms of this study achieved CCR rates of 21.2% and 50%, respectively. Another study tested 100 mg/m2 cisplatin every 3 weeks plus 5-FU versus the cisplatin regimen plus UFT 200 mg/M2/d and vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 every 21 days [16]. Again, CCR rates were only 36% and 31%, respectively. Conversely, a pilot CTRT study by Goodman et al. in which patients were treated with cisplatin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4 and 18 to 20 during radiotherapy had an HCR rate of 54% [17]. Consequently, CTRT has significantly better rates of complete response and negative biopsy than other studies regarding the treatment of SCCHN.

Figure 2: Disease-Free Survival in Stage III and IV SCCHN: CTRT versus control. Disease free survival probability for patients who underwent CTRT treatment (dashed line) versus control treatment (straight line). Kaplan-Meier survival curves display the number of months after treatment was completed. Survival was 79.07% CTRT versus 58.33% control. Log rank test P=0.16.

Radical, curative head and neck surgery, with its high complication rates and resulting cosmetic and functional morbidities, has been a major concern in the treatment of SCCHN, particularly in elderly patients. Organ preservation is extremely important to the patient; however, organ function is often compromised when surgery is used to treat SCCHN. Additionally, patients with SCCHN frequently present with unresectable, advanced stage disease at diagnosis [18]. Thus, CTRT was specifically designed to eliminate surgery from the treatment regimen whenever possible. Patients who responded to this treatment not only had a negative biopsy, but also were able to retain full function of their upper aerodigestive tract. Furthermore, only 13% of patients who underwent CTRT required composite resections with complex reconstruction; thus organ preservation was achieved in 87% of CTRT patients. Conversely, a comparison study of two treatments, cisplatin 100 mg/m2 on day 1, 23, and 45 during radiotherapy versus cisplatin 40 mg/m2 weekly for 6 weeks, found that 44.6% and 37% of patients, respectively, required post-treatment surgery [19]. Thus, although CTRT did not differ from control regarding overall surgery, CTRT was more successful in reducing the need for post-treatment surgery when compared to other regimens.

Metastatic disease developed in 2% of the CTRT patients after treatment, while 14% of patients in the control group experienced distant recurrence. The randomized clinical trial reported by Posner et al. documented distant metastasis in 5% of the TPF regimen group and in 9% of the PF group [2]. Thus, the results here indicate that metastatic disease after CTRT distant metastases is comparable to and possibly lower than these published regimens.

The Kaplan-Meier curve for overall survival indicates a diseasefree survival for 79% of CTRT patients compared to 58% of control patients at three years post-treatment. Cohen’s review of eight prominent chemoradiotherapy studies for advanced stage SSCHN found survival percentages ranging from 17.5% to 55% for three year follow-up periods [3]. In the present investigation, this trend toward increased long-term survival as evidenced by both of the Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival and disease-free survival suggest that CTRT is comparable with other treatment regimens in terms of survival, and may possibly be more successful. Future studies of CTRT should focus on consistent follow-up with patients for fine to ten years.

There are several limitations in the present study. Of course, a retrospective review is lower on the evidence-based medicine scale than would be a prospective investigation. Incomplete information on individual patients and follow-up data that was not universal restricted analyses, as well. Additionally, the control group was not enrolled by pre-established criteria, and, therefore, varied in the treatments that were applied, resulting in a very heterogeneous array of therapeutic control regimens. Consequently, this study was not a strict two-armed study. Nevertheless, all of the non-CTRT cancer treatments of the control group were currently accepted standard of care for Stage III and IV SCCHN, and thus comprised a reasonably realistic comparison to CTRT. Radiation therapy varied modestly within both patient groups. However, the CTRT chemotherapy regimen was administered consistently. Lastly, the sample sizes were limited by the retrospective nature of the study.

By comparing the CTRT regimen not only to our control group, but also to other SCCHN regimen publications, the therapeutic benefits of CTRT and their potential for future application are identified. The impressively high CCR and HCR rates achieved in this study while simultaneously reducing toxicity are major improvements to the multi-modality treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Reduced distant metastases is another positive outcome from CTRT. Lastly, CTRT is comparable in terms of survival with other published regimens, adding effective disease control to minimized adverse treatment effects. Based on the results presented in this paper, we believe that pre-surgery fractionated low-dose cisplatin administered simultaneously with high-dose radiotherapy is a feasible and useful for the management of advance, operable Stage III and Stage IV SCCHN.

References

- http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-036845.pdf.

- Posner MR, Hershock DM, Blajman CR, Elizabeth Mickiewicz, Eric Winquist, et al. (2007) Cisplatin and fluoracil alone or with docetaxel in head and neck cancer. NEJM 357: 1705-1715.

- Cohen EEW, Lingen MW, Vokes EE. (2004) The expanding role of systemic therapy in head and neck cancer J Clin Oncol 22: 1743-1752.

- Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, Wagner H Jr, Kish JA, et al. (2003) An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 21: 92-98.

- Wolff HA, Overbeck T, Roedel RM, Hermann RM, Herrmann MK, et al. (2009) Toxicity of daily low dose cisplatin in radiochemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135: 961-967.

- Agarwala SS, Cano E, Heron DE, JohnsonJ, MyersE, et al. (2007) Long-term outcomes with concurrent carboplatin, paclitaxel and radiation therapy for locally advanced, inoperable head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol 18: 1224–1229.

- Puc MM, Chrzanowski FA, Tran HS, Liu L, Glicksman AS, et al. (2000) Preoperative chemotherapy-sensitized radiation therapy for cervical metastases in head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126: 337-342.

- Koness RJ, Glicksman A, Liu L, Coachman N, Landman C, et al. (1997) Recurrence patterns with concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy and accelerated hyperfractionated radiotherapy in stage III and IV head and neck cancer patients. Am J Surg 174: 532-535.

- Glicksman AS, Wanebo HJ, Slotman G, Li Liu, Christine Landmann, et al. (1997) Concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy and hyperfractionated radiotherapy with late intensification in advanced head and neck cancer. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys 39: 721-729.

- Greene FL (2002) AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook: From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer, New York.

- National Cancer Institute (2009) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. NCI, NIH, DHHS, NIH publication.

- Bourhis J, Lapeyre M, Tortochaux J, Lusinchi A, Etessami A, et al. (2011) Accelerated radiotherapy and concomitant high dose chemotherapy in non resectable stage IV locally advanced HNSCC: Results of a GORTEC randomized trial Rad Onc 100: 56-61.

- Castro G, Snitcovsky IML, Gebrim EM, Leitão GM, Nadalin W, et al. (2007) High-dose cisplatin concurrent to conventionally delivered radiotherapy is associated with unacceptable toxicity in unresectable, non-metastatic stage IV head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 64: 1475-1482.

- Rampino M, Ricardi U, Munoz F, Reali A, Barone C, et al. (2011) Concomitant adjuvant chemoradiotherapy with weekly low-dose cisplatin for high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a phase II prospective trial. Clin Oncol 23: 134-140.

- Paccagnella A, Ghi MG, Loreggian L, Buffoli A, Koussis H, et al. (2010) Concomitant chemoradiotherapy versus induction docetaxel, cisplatin and 5 fluorouracil (TPF) followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer: a phase II randomized study. Ann Oncol 21: 1515-1522.

Citation: Slotman GJ (2015) Simultaneous Fractionated Cisplatin and Radiation Therapy in the Treatment of Advanced Operable Stage III and IV Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity and Pharynx. Otolaryngol (Sunnyvale) 6:215. DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000215

Copyright: © 2015 Slotman GJ. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 10286

- [From(publication date): 11-2015 - Apr 04, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 9455

- PDF downloads: 831