Shiga Toxine Associates With Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome A Rare Cause Of Severe Neurological Involvement

Received: 01-Nov-2023 / Manuscript No. JNID-23-120613 / Editor assigned: 03-Nov-2023 / PreQC No. JNID-23-120613 / Reviewed: 20-Nov-2023 / QC No. JNID-23-120613 / Revised: 25-Nov-2023 / Manuscript No. JNID-23-120613 / Published Date: 29-Nov-2023 DOI: 10.4172/2314-7326.1000473 QI No. / JNID-23-120613

Abstract

Background: Hemolytic uremic syndrome is a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia discrabed as a clinical triad of acute kidney injury, hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. The infectieuse etiology is most frequent, especially following contamination by Shiga toxin produced by Escherichia Coli. We présent the case of à patient with shiga toxin produced by Escherichia Coli presenting a multi-organ failure.

Case presentation : A 48-year-old man, presented no bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain 2 hours after eating a poorly preserved meat. Following the gradual worsening of clinical signs and the appearance of bloody diarrhea and respiratory distress, the patient was admitted in our hospital’s emergency department. Clinical examination reveals an apyretic, tachycard and polypneic patient. The pulmonary auscultation finds bilateral rousing rales. The initial laboratory test showed acute renal failure. Haemolytic anaemia was suspected in the presence of anaemia with elevated LDH and haptoglobin levels and thrombocytopenia. A thoraco-abdomino-pelvic Computed Tomography scan showed circumferential rectocolic thickening in favor of infectious colitis, acute lesional pulmonary edema and Balthazar stage C pancreatitis. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia Coli producing Shiga toxin 2 was found in stool analysis. The most likely diagnosis was hemolytic uremic syndrome due to Shiga toxin producing Esherichia coli. On the eighth day, the patient presented a malignant hypertensive spike followed by bilateral blindness and then the appearance of generalised epileptic seizures. The patient mental statut worsened and he was died 20 days after onset symptoms.

Conclusion: Hemolytic uremic syndrome due to Shiga toxine producing by Esherichia Coli is a rare condition in adults. The prognosis depends on damage to vital organs, particularly the central nervous system. Improving the prognosis requires early diagnosis and replacement therapy for renal function or even plasmapheresis.

Keywords

Hemolytic uremic syndrome; Shiga toxin; Acute kidney injury; Neurological involvement.

Introduction

Hemolytic uremic syndrome is a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia described as a clinical triad of acute kidney injury, hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia [1].

The infectious etiology is the most common, especially following contamination by Shiga toxin produced by Escherichia Coli [2]. It is a rare condition in adults [3]. The extra-renal manifestations of this syndrome can affect the heart, lungs, pancreas, digestive tract and central nervous system [4 ]. The involvement of the central nervous system is rare and has a grave prognosis [3].

We report the case of a patient with Shiga toxin-producing by Escherichia coli presenting with multi-organ failure.

Case report

A 48-year-old man, with no relevant medical history, presented non-bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain 2 hours after eating poorly preserved meat. An initial treatment based on oral rehydratation solutions and analgesics was given. Following the gradual worsening of clinical signs and the appearance of bloody diarrhea and respiratory distress, the patient was admitted to our hospital’s emergency department.

Clinical examination revealed an apyretic and polypneic patient. His respiratory rate was 35 cycles per minute, his oxygen saturation was 87% and his heart rate was 118 bpm. The pulmonary auscultation found bilateral rousing rales. The initial laboratory tests showed acute renal failure, with creatinine at 19,5mg/L , urea at 3,96 g/L , and hyperkalaemia at 6,4 mmol/L. Haemolytic anaemia was suspected in the presence of anaemia at 8 g/ dl with elevated LDH and haptoglobin levels and thrombocytopenia at 95,000 /mm.

The patient was put on high concentration oxygen. A thoracoabdomino- pelvic computed tomography scan showed circumferential recto-colic bowel wall thickening in favor of infectious colitis, acute lesional pulmonary edema and Balthazar stage C pancreatitis. The patient was immediately transferred to intensive care to receive rehydration, oxygenation, broad-spectrum antibioticsand treatment for reduced kalaemia.

A stool analysis identified the presence of enterohemorrhagic Shiga toxin-producing by Escherichia coli. The most likely diagnosis agreed upon was hemolytic uremic syndrome due to Shiga toxin producing by Escherichia coli.

Given the increase in kidney function, the patient underwent hemodialysis at a frequency of one session every 2 days as well as plasma exchange and blood transfusion.

The initial clinical evolution was marked by improvement. On the eighth day, the patient presented a malignant hypertensive spike followed by bilateral blindness and then the appearance of generalized epileptic seizures that required intubation.

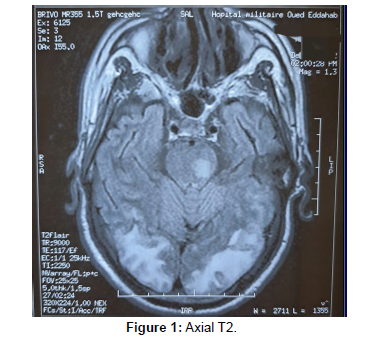

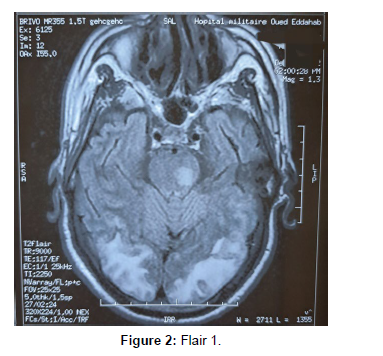

An emergency brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without intravenous contrast was carried out and showed signs in favor of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome with centropontic lesions (Figures 1-2).

The patient’s mental status worsened and passed away after 16 days of admission and 20 days after his onset symptoms.

Discussion

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) is a complex disorder characterized with the clinical triad of acute renal failure, haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia [3].

The term HUS includes two entities: typical HUS caused by shiga toxin produced by Escherichia coli, and atypical HUS caused by deregulation of the alternative complement pathway [5].

While HUS associated with Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) is a rare entity in adults [3], it remains a frequent cause of acute kidney injury in children, accounting for 85% to 90% of cases [2], and can cause significant morbidity and mortality during the acute phase [6].

In addition to the renal damage caused by STEC, extra-renal manifestations can occur, especially in the central nervous system, gastrointestinal, pancreatic, musculoskeletal and cardiac systems [6]. The pathophysiology of HUS is complex [7]. STEC HUS causes thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) with the formation of micro thrombi in the small vessels of organs, particularly the kidney [8].

It is assumed that E. coli adhere to cells in the intestinal mucosa during infection and secrete Shiga toxin (Stx), which damages blood vessels in the digestive tract, allowing Stx to enter the bloodstream and reach target organs. Stx binds to cells expressing glycosphingolipid globotriaosylamide (Gb3Cer) receptors. Stx is then endocytosed and induces intracellular inhibition of protein synthesis, causing cell death by apoptosis [9]. Endothelial dysfunction thus activates a cascade of events leading to leukocyte attraction, fibrin deposition and, consequently, microthrombus formation [10].

The digestive tract may be affected from the oesophagus to the perianal region. Bloody diarrhea is common in the prodromal phase of STEC HUS and may continue beyond this phase it [6]. Various disorders could be observed, such as ileus, intestinal distension, intestinal stricture, perforation, necrosis, rectal prolapse, hepatocellular and cholestasis [11, 12 ]. Complications such as pseudomembranous colitis and toxic megacolon have also been reported [13].

Pancreatitis is a serious complication of STEC infection. Elevated amylase and lipase levels are common during the acute phase [6]. The positive diagnosis and severity of the disease are confirmed by an abdominal CT scan [14, 15].

The involvement of the central nervous system is one of the rarest complications, but one that significantly increases morbidity and mortality [6]. Clinical signs range from epileptic seizures to decreased levels of consciousness and focal motor deficits [16]. While some patients do not develop neurological damage, others may develop long-term sequelae. Signorini et al. report the case of a 20-month-old girl with STEC HUS who developed severe neurological disorders, including seizures, coma, fixed midriasis, blindness, aphasia, strabismus and motor deficits [17]. Cerebral MRI remains the diagnostic method procedure of choice for analyzing these lesions. It usually reveals symmetrical hyperintensities in the basal ganglia and thalamus [18].

Cardiac involvement is rare. It can manifest itself with high blood pressure, congestive heart failure or haemodynamic instability. The latter may be the result of tachyarrhythmia caused by HUS, electrolyte imbalance or toxic myocarditis followed by dilated cardiomyopathy [11, 19].

Conclusion

Hemolytic uremic syndrome due to Shiga toxin-producing by Esherichia Coli is a rare condition in adults. The prognosis depends on the damage to vital organs, particularly the central nervous system. Improving the prognosis requires early diagnosis and renal replacement therapy or even plasmapheresis.

Acknowledgement

All the authors are thankful for providing the necessary facilities for the preparation the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare no funding in this report.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Noris M, Remuzzi G (2005) Hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 16:1035.

- Cody EM, Dixon BP (2019) Hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am 66:235-46.

- Abdelrahman A, Nada A, Park E, Humera A (2020) Neurological involvement and MRI brain fndings in an adult with hemolytic uremic syndrome. Radiology Case Reports; 15:2056-2058.

- Khalid M, Andreoli S (2019) Extrarenal manifestations of the hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC HUS). Pediatr Nephrol 34: 2495-507.

- Goodship THJ, Cook HT, Fakhouri F (2017) Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy: conclusions from a ‘Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes’ (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int 91: 539-551.

- Myda K, Sharon A (2019) Extrarenal manifestations of the hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC HUS). Pediatric Nephrology 34:2495-2507.

- Fakhouri F, Zuber J, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Loirat C (2017) Haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet (London, England) 390:681-96.

- Zoja C, Buelli S, Morigi M (2010) Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: pathophysiology of endothelial dysfunction. Pediatr Nephrol 25:2231-2240.

- Wengenroth M, Hoeltje J, Repenthin J, Meyer T, Bonk F, et al. (2013) Central Nervous System Involvement in Adults with Epidemic Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 34:1016-21.

- Fitzpatrick MM, Shah V, Trompeter RS, Dillon MJ, Barratt TM, et al. (1992) Interleukin-8 and polymorphoneutrophil leucocyte activation in hemolytic uremic syndrome of childhood. Kidney Int 42: 951-956.

- Scheiring J, Andreoli SP, Zimmerhackl LB (2008) Treatment and outcome of Shiga toxinassociated hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Pediatr Nephrol 23: 1749-6.

- Riley MR, Lee KK (2004) Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome and acute hepatocellular cholestasis: a case report. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 38: 352-354.

- Tapper D, Tarr P, Avner E, Brandt J, Waldhausen J, et al. (1995) Lessons learned in the management of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. J Pediatr Surg 30:158-163.

- Andreoli S, Bergstein J (1987) Exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency and calcinosis after hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Pediatr 110:816-817.

- Robitaille P, Gonthier M, Grignon A, Russo P (1997) Pancreatic injury in the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 11:631-632.

- Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Fakhouri F, Garnier A (2013) Genetics and outcome of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a nation-wide French series comparing children and adults. CJASN 8: 554-562.

- Signorini E, Lucchi S, Mastrangelo M, Rapuzzi S, Edefonti A et al. (2000) Central nervous system involvement in a child with hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 14:990-992.

- Steinborn M, Leiz S, Rüdisser K (2004) CT and MRI in haemolytic uraemic syndrome with central nervous system involvement: distribution of lesions and prognostic value of imaging fndings. Pediatr Radiol 34: 805-10.

- Oakes RS, Siegler RL, McReynolds MA (2006) Predictors of fatality in postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatrics 117: 1656-62.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Jaouhari SD, Bouhabba N, Hamdani Z, Baalal H, Kherrasse A (2023)Shiga Toxine Associates With Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome A Rare Cause OfSevere Neurological Involvement. J Neuroinfect Dis 14: 473. DOI: 10.4172/2314-7326.1000473

Copyright: © 2023 Jaouhari SD, et al. This is an open-access article distributedunder the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permitsunrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided theoriginal author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 212

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Sep 18, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 173

- PDF downloads: 39