Editorial Open Access

Setting a Higher Standard in Cancer Care: Isn' t it Time to Bring about a Change in Cancer Palliation?

Michael Silbermann1* and Mohammed A Jaloudi21Technion, The Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC), Israel Institute of Technology and Haifa, Israel

2Department of Oncology, Tawam Hospital, Al-Ain, Abu Dhabi, UAE

- *Corresponding Author:

- Michael Silbermann

Israel Institute of Technology

The Middle East Cancer Consortium, Israel

Tel: 972-482-447-94

Fax: 972-483-463-38

E-mail: cancer@mecc-research.com

Received date December 30, 2013; Accepted date January 05, 2014; Published date January 10, 2014

Citation: Silbermann M, Jaloudi MA (2014) Setting a Higher Standard in Cancer Care: Isn’t it Time to Bring about a Change in Cancer Palliation? J Palliat Care Med 4:e128. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000e128

Copyright: © 2014 Silbermann M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

For most cancer patients in the Middle East, “palliative” is a vague term, a medical approach they have hardly heard of let alone understand. The focus of palliative care is to prevent patients from suffering with the aim to provide relief. It’s about providing the best possible quality of life by minimizing the burden of a chronic, life-threatening disease [1]. It is, therefore, important to correct the misunderstanding of the role of palliative care in treating cancer patients. To date, regrettably, many still view palliative care as “giving up”. Yet, by complying with the patient’s desire for self-dignity, we fulfill his/her basic human and constitutional right [2].

Unfortunately, we still face barriers to the effective integration of palliative care in cancer care, including gaps in education and research and a cultural stigma that equates palliative care with end-of-life care. It is our obligation, therefore, to address these obstacles in order to achieve the seamless integration of palliative care across the continuum of cancer care for all patients and their families [3]. Let’s remember that for most cancer patients, one of the most noticeable benefits of palliative care (which is also called supportive care) is the relief of physical pain, since if patients feel better physically, they are able to continue with their cancer treatment [4].

In the past two years, the Tawam Hospital in Al-Ain, Abu Dhabi, in the United Arab Emirates, in affiliation with Johns Hopkins Medicine, initiated, sponsored and supported annual conferences (the International Emirates Oncology Conference) to improve physician and nursing training in cancer care generally and palliative care in particular. This year’s conference, held at the Emirates Palace in Abu Dhabi on November 14-16, 2013, dedicated an entire session to pain assessment, as well as management and the use of opioids for cancer patients.

To date, most Middle Eastern countries are categorized as low- or middle-income countries suffering from limited treatment options for most cancers, while patients present late with advanced malignancies [5]. For the most part, these patients suffer from moderate to severe pain, which, if unrelieved, may escalate suffering and functional impairment, and affect sleep and appetite, leading to emotional distress. Due to the reality that there are relatively few oncologists and palliative care specialists in many of the Middle Eastern countries, many cancer patients are treated by health professionals lacking the essential skills for pain management, as there was no provision for palliative care in their training. Several international declarations (Korean [6], Cape Town [7]) have stated that pain-relieving drugs should to be available and accessible at all levels, including the community. Regretfully, however, this is not the case in most Middle Eastern countries.

In order to improve and sustain palliative care services in a country, four fundamental measures need to be considered: government policy, drug availability, education and implementation [8].

Opioids are key in the management of severe pain, with morphine consumption a proxy measure of the degree of pain control. In order to further elucidate the current situation as related to the availability and accessibility of opioids for the management of cancer pain, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) partnered with the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) in launching a global survey: The Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) project. Its aims included evaluating the formulary availability and cost to the consumer of the seven opioid formulations deemed essential by the WHO and the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC). In addition, the study aimed to evaluate the actual barriers that impede accessibility [9]. The Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC), which was invited to join this project as a collaborating partner organization, succeeded in bringing in 16 out of 24 Middle Eastern countries (representing 76% of the target countries) to actively participate in this project. On a population basis, the current Middle Eastern dataset is relevant to 329 million of the region’s 403 million people, representing 82% of the target population.

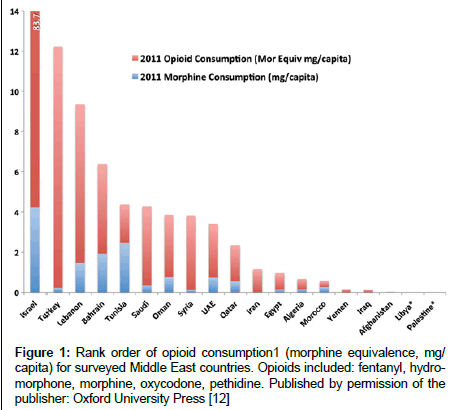

It became apparent that by and large the Middle East still has very low medical opioid consumption [10,11] (Figure 1). In contrast to the global consumption of opioids, which has increased significantly during the last 30 years, there has been very little increase in the Middle East (Figure 2).

The GOPI study is the first comprehensive study of opioid availability and the accessibility of opioid in the Middle East [12].

The main findings in this survey are as follows:

Formulary Availability and Cost of Opioids for Cancer Pain

Saudi Arabia, Israel and Qatar had all seven essential opioid formulations available: codeine; immediate-release per os morphine (tablet or liquid); controlled-release per os morphine; injectable morphine; oxycodone per os immediate release; fentanyl transdermal; and methadone per os immediate release. In the majority of countries (11 of 16), the cost of these medications was free, or <25% of the drug cost was charged to the patient.

Regulatory Restrictions to Accessibility

Almost all countries have considerable restrictions on the accessibility of opioid analgesics.

Requirement for Permission/Registration of Patients to Render them Eligible to Receive an Opioid Prescription

Turkey, Morocco and Israel had no restriction on the eligibility of a patient to receive a prescription for opioid analgesics. In all other countries, patients required a permit or needed to be registered to receive opioids even in an inpatient setting.

Requirement for Physicians and Other Clinicians to Receive Special Authority/a License to Prescribe Opioids

In Morocco, Afghanistan and Israel, all physicians were permitted to prescribe opioids. In most other countries, special authorization was required for both surgeons and family doctors.

Prescription Limits

Eight countries allow physicians to prescribe an amount of opioid analgesics to a patient for more than 2 weeks.

Limitations on Dispensing Privileges

Morocco and Afghanistan reported opioids as being available from any pharmacy, and that they were usually available. Most other countries reported that opioids were available only in hospital pharmacies.

Provision for Opioid Prescribtion in Emergency Situations

Only in Afghanistan were pharmacies allowed to prescribe in emergency situations. Few countries allowed for telephone or faxed prescriptions or nurse-generated prescriptions.

AcUse of Stigmatizing Terminology for Opioid Analgesics in Regulations

Eight countries had negative language in drug laws: Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Syria and Turkey.

Cancer continues to be a growing problem throughout the world, with a substantial increase in cancer incidence in developing countries (predicted at 70% by the year 2020). Significantly, inadequate treatment of acute and chronic pain is an enormous problem the world over, but especially in resource-poor countries: 80% of the world population lacks adequate access to pain treatment [13-17], especially as most cancer patients in the Middle East present with advanced disease [18,19]. The issue of very low opioid consumption in Middle Eastern countries is well known [20-24], with all surveyed countries, except Israel, indicating <10% of the anticipated Adequacy of Consumption Measure (ACM) for opioids (Table 1).

| S-DDD | %ACM 2006 | S-DDD | %ACM 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–1997 | 2009–2007 | |||

| Afghanistan | ND | ND | ND | 0.01 |

| Algeria | 60 | 0.3 | 160 | 0.63 |

| Bahraina | 100 | 5.8 | 225 | 6.55 |

| Egypt | 45 | 0.76 | 50 | 1.29 |

| Iran | 20 | 1.46 | 40 | 1.7 |

| Iraq | 5 | ND | 10 | 0.21 |

| Israel | 1300 | 38 | 3500 | 42.31 |

| Jordana | 50 | 5.81 | 80 | 5.24 |

| Kuwaita | 70 | 5.12 | 185 | 13.16 |

| Lebanon | 80 | 0.476 | 180 | 3.55 |

| Libya | 10 | 4.85 | 75 | 2.43 |

| Morocco | 20 | 0.54 | 30 | 0.82 |

| Oman | 40 | 3.15 | 60 | 2.99 |

| Palestine | – | – | – | – |

| Qatar | 110 | 7.1 | 160 | 4.24 |

| Saudi | 50 | 4 | 190 | 5.76 |

| Syria | 20 | 3.81 | 80 | 5.16 |

| Tunisia | 60 | 3.46 | 120 | 2.64 |

| Turkey | 120 | 5.74 | 580 | 7.28 |

| UAEa | 40 | 1.84 | 180 | 4.68 |

| Yemen | 0 | 0.12 | 10 | 0.24 |

Note: %ACM, percentage of Adequacy of Consumption Measure; S-DDD, defined daily dose per million persons per day. Published by permission of the publisher: Oxford University Press.

Table 1: Comparison of DDD and %ACM [12-14] aCountries that did not respond to GOPI survey.

Notably, however, even in countries with very limited opioid formularies, transdermal fentanyl was usually among those medicines available, as has been recently reported [10].

One of the important lessons to be learned from this study is that education in palliative care is paramount in ensuring a change in culture and practice. Addressing the barrier of health professionals’ lack of knowledge and skill in pain management is crucial and timely, as is advocacy of the need for palliative care practices [5], since inadequate training of health care workers in the use of opioids contributes to the absence of badly needed advocacy for the availability of these drugs. In a survey of final- year medical students in Saudi Arabia, half of the respondents considered cancer pain as untreatable, 40% considered it a minor problem, and almost 60% considered the risk of substance developing syndrome to be high even with a legitimate opioid prescription [25]. In a survey of 122 physicians in six university hospitals in Teheran, inadequate education and training in this aspect of care was highlighted as a significant barrier to pain management [26]. The problem of lack of training is critical among non-oncology specialists in hospitals, and more specifically in the community. Almost 70% of oncologists at the National Center for Cancer Care and Research in Qatar reported an awareness of guidelines for pain relief, but only 60% indicated that they applied them in their practice [27].

In a recent letter to the editor of the Journal of Clinical Oncology, Charalambous H and Silbermann M called for all oncology trainees, as well as oncology specialists, to obtain palliative care training [28], as did Jazieh in Saudi Arabia [29]. At the same time, the public at large should be informed and educated, as most patients and their families are concerned about the use of opioids for the management of cancer pain [14,30,31].

The palliative care session in this year’s Emirates Oncology Conference served as an additional link in the chain of ongoing educational activities in the region, whereby Tawam Hospital together with international and national organizations – i.e., the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the Arab Medical Association Against Cancer (AMAAC), Euro-Arab School of Oncology (EASO), Breast- Gynecological International Cancer Society (BGICS), and the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC) together with the United Arab Emirates University (UAEU) and the Abu Dhabi Health Services (SEHA) – have taken steps to improve physicians’ and nurses’ training in cancer pain control through the use of opioids. The data and findings of the recent ESMO & EAPC survey served as an important basis for fruitful discussions for future training programs in the region. Such collaboration between a regional referring hospital and education -oriented organizations will eventually make better use of existing resources and promote a better future for cancer patients, their families and the caregivers themselves. The ultimate goal would be to create a nucleus of local advocates who will further disseminate knowledge and firsthand experience associated with care generally and pain management in particular.

Further, we hope that such a collaborative effort will produce tailormade recommendations for individual countries in the region through local governments, health care professionals, other key decisionmaking bodies, and the general public. Such efforts will eventually pay dividends via advocacy, education and regulatory reforms. We must bear in mind that although such progress is incremental, it is real, embedding the potential for practical regulatory and clinical changes through concerted and sustained efforts.

The WHO Secretariat has been requested by member states to submit a resolution to the 2014 World Health Assembly laying out the importance of palliative care and appropriate access to opioids in public health. We hope that the recent findings regionally and globally in this area will strengthen such a resolution, setting out a road map for the international community to improve availability and access to better cancer care services [32]. While each country in our region will be responsible for improving cancer care services for its residents, there is a growing potential for the impact of global and regional organizations, which can provide powerful support for advocacy with national regulatory authorities.

In the past, it has often been easier for individual associations, societies and NGOs to work independently within their country. Yet, a collaborative and coordinated approach, which we hope will emanate from the Emirates Oncology Conferences, harnessing the expertise of professional leaders across the field of cancer care, can create a united voice and reach the tipping point for real change and sustained impact [32]. We believe that through the collaboration and efforts of the leading oncology services and organizations in the region who participate in the EOCs, several regulatory issues related to pain control can be overcome.

References

- Berman A (2012) Living life in my own way--and dying that way as well. Health Aff (Millwood) 31: 871-874.

- Martin C, Granton J (2012) Rasouli case may help reduce misunderstanding about role of palliative care. The Globe and MAIL Inc.

- Ramchandran K, Von Roenn JH (2013) Palliative care always. Oncology 27: 13-6, 27-30, 32-4 passim.

- Tutt B (2012) Palliative care may offer survival benefits. Oncolog 57: 4-6.

- Namukwaya E, Leng M, Downing J, Katabira E (2011) Cancer pain management in resource-limited settings: a practice review. Pain Res Treat 2011: 393404.

- The Korea Declaration (2005) Report of the Second Global Summit on National Hospice and Palliative Care Associations, Seoul.

- Mpanga Sebuyira L, Mwangi-Powell F, Pereira J, Spence C (2003) The Cape Town Palliative Care Declaration: home-grown solutions for sub-Saharan Africa. J Palliat Med 6: 341-343.

- Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD (2007) The public health strategy for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 33: 486-493.

- Cherny NI, Cleary J, Scholten W, Radbruch L, Torode J (2013) The Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) project to evaluate the availability and accessibility of opioids for the management of cancer pain in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East: Introduction and methodology. Ann Oncol 24: XI, 7-13.

- Silbermann M (2011) Current trends in opioid consumption globally and in Middle Eastern countries. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 33 Suppl 1: S1-5.

- Silbermann M (2010) Opioid use in Middle Eastern countries in comparison to the United States- status quo. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 11: 1-7.

- Cleary J, Silbermann M, Scholten W, Radbruch L, Torode J, et al. (2013) Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in the Middle East: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI). Ann Oncol 24: XI51-59.

- Dohlman LE, Warfield CA (2012) Pain management in developing countries. Am Soc Anesthesiologists 76: 18-20.

- Al Qadire M, Tubaishat A, Aljezawi MM (2013) Cancer pain in Jordan: prevalence and adequacy of treatment. Int J Palliat Nurs 19: 125-130.

- Yamout R, Ayoub E, Naccache N, Abou Zeid H, Matar MT, et al. (2013) Opioid drugs. What is next for Lebanon. Lebanese Medical J 61:210-215.

- Al-Bahrani B (2013) Prospects of changing pattern of opioid consumption in Middle Eastern countries: current situation and future challenges. Oman National Oncology Center, Royal Hospital, Muscat, Personal communication.

- Lopez-Gonzalez L (2013) First ever guidelines to manage pain in cancer patients to be released.

- Al-Kahiry W, Omer HH, Saeed NM, Hamid GA (2011) Late presentation of breast cancer in Aden, Yemen. Gulf J Oncol 9: 7-11.

- Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, Hessissen L, Madani A, et al. (2012) MECC regional initiative in pediatric palliative care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 34 Suppl 1: S1-11.

- Silbermann M, Arnaout M, Daher M, Nestoros S, Pitsillides B, et al. (2012) Palliative cancer care in Middle Eastern countries: accomplishments and challenges. Ann Oncol 23 Suppl 3: 15-28.

- Silbermann M, Epner DE, Charalambous H, Baider L, Puchalski CM, et al. (2013) Promoting new approaches for cancer care in the Middle East. Ann Oncol 24 Suppl 7: vii5-10.

- Seya MJ, Gelders SF, Achara OU, Milani B, Scholten WK (2011) A first comparison between the consumption of and the need for opioid analgesics at country, regional, and global levels. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 25: 6-18.

- Duthey B, Scholten W (2013) Adequacy of Opioid Analgesic Consumption at Country, Global, and Regional Levels in 2010, Its Relationship With Development Level, and Changes Compared With 2006. J Pain Symptom Manage .

- International Narcotics Control Board (2011) Report of the International Narcotics Control Board on the Availability of Internationally Controlled Drugs: Ensuring Adequate Access for Medical and Scientific Purposes. United Nations, New York, 88

- Kaki AM (2011) Medical students' knowledge and attitude toward cancer pain management in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 32: 628-632.

- Eftekhar Z, Mohaghegh MA, Yarandi F, Eghtesadi-Araghi P, Moosavi-Jarahi A, et al. (2007) Knowledge and attitudes of physicians in Iran with regard to chronic cancer pain. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 8: 383-386.

- Zeinah GF, Al-Kindi SG, Hassan AA (2013) Attitudes of medical oncologists in Qatar toward palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 30: 548-551.

- Charalambous H, Silbermann M (2012) Clinically based palliative care training is needed urgently for all oncologists. J Clin Oncol 30: 4042-4043.

- Jazieh AR (2013) Capacity building in palliative care. J Palliative Care Med 3:138.

- McCarthy P, Chammas G, Wilimas J, Alaoui FM, Harif M (2004) Managing children's cancer pain in Morocco. J Nurs Scholarsh 36: 11-15.

- Faris M, Al-Bahrani B, Emam Khalifa A, Ahmad N (2010) Evaluation of the prevalence, pattern and management of cancer pain in oncology department, The Royal Hospital, Oman. Gulf J Oncol 1: 23-28.

- Cleary J, Radbruch L, Torode J, Cherny NI (2013) Next steps in access and availability of opioids for the treatment of cancer pain: reaching the tipping point? Ann Oncol 11: 60-64.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15019

- [From(publication date):

February-2014 - Jul 19, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10377

- PDF downloads : 4642