Research Article Open Access

Seaweed Incorporated Diet Improves Astaxanthin Content of Shrimp Muscle Tissue

Kunal Mondal1*, Subhra Bikash Bhattacharyya2 and Abhijit Mitra21Faculty of Fishery Sciences, West Bengal University of Animal and Fishery Sciences, Kolkata-700094, India

2Department of Oceanography, Techno India University, Kolkata- 700091, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Kunal Mondal

Faculty of Fishery Sciences

West Bengal University of Animal and Fishery Sciences

Kolkata-700094, India

E-mail: chow@affrc.go.jp

Received date March 09, 2015; Accepted date April 25, 2015; Published date April 27, 2015

Citation: Mondal K, Bhattacharyya SB, Mitra A (2015) Seaweed Incorporated Diet Improves Astaxanthin Content of Shrimp Muscle Tissue. J Marine Sci Res Dev 5:161. doi:10.4172/2155-9910.1000161

Copyright: © 2015 Mondal K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Marine Science: Research & Development

Abstract

Marine shrimp (Penaeus monodon) is one of the major candidate species for export oriented aquaculture which dominates the seafood market in regions of European Union, Southeast Asia and USA. Carotenoid rich seafood has now become one of the important criteria in determining the quality of the product to be exported. Recent trends in supplementing fish diets with natural pigment source is an alternative to the utilization of expensive synthetic pigments. In this context, green seaweed Enteromorpha intestinalis was selected as a source of carotenoid for inclusion in the formulated diet of Penaeus monodon. Astaxanthin being an important category of carotenoid pigment was monitored in shrimp muscle tissue during the feeding trial. Significant variation (p<0.05) was observed between the experimental groups as confirmed through ANOVA thus exhibiting higher astaxanthin content of shrimps (18.70 ± 4.48 ppm) fed with seaweed incorporated diet as compared to control (15.80 ± 2.33 ppm). The present experiment therefore emphasizes on the quality improvement of aquaculture product through dietary inclusion of seaweed as a source of astaxanthin.

Keywords

Penaeus monodon; Seaweed; Astaxanthin content; Quality improvement

Introduction

Inclusion of algae as dietary supplement in animals have been investigated by researchers for years as a source of pigment [1]. In context to aquaculture, the effects of dietary inclusion of algae have resulted in improved performance including better animal product quality [2-4]. To be more specific the commercial production of shrimps and prawns as an edible item represents one of the fastest growing areas of aquaculture [5] with high consumer appeal and attractive market due to their body colouration or pigmentation which is a direct measure of its body astaxanthin content. Carotenoid utilization by various aquatic species is well documented since it plays a regulatory role in providing antioxidant and pro-vitamin ‘A’ activity, enhancing immune response, improved reproductive performance, growth, maturation and photo-protection [6]. These natural compounds also help the species to combat against stressful environment [7]. Algae and higher group of plants are the major producers of carotenoid which comprises a family of over 600 natural fat soluble pigments [8]. Studies reveal that alternative utilization of plant pigments in formulated diets have improved the body pigmentation of farmed crustaceans, particularly penaeids in order to achieve better market price [9,10].

Therefore the present work is an attempt to utilize E. intestinalis as a natural astaxanthin source for farmed tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) in relation to its quality improvement.

Materials and Methods

Collection of seaweed and preparation of experimental diets

Live and healthy E. intestinalis was collected from Bali Island (22°04’35.17’’ N latitude and 88°44’ 55.70’’ E longitude) of Sundarbans mangrove eco-region during low tide condition. The collected material was rinsed in ambient water and then with distilled water, oven-dried at 50°C and finally processed to make powder. Experimental diet was formulated through incorporation of the particular seaweed (Diet ENT) at a level of 5%. Simultaneously a control diet (Diet C) was also formulated to study the comparative performance (Table 1).

| Ingredients | Diet C | Diet ENT |

|---|---|---|

| Fish meal | 35 | 30 |

| Soybean oil cake | 11 | 11 |

| Mustard oil cake | 11 | 11 |

| Rice polish | 23 | 23 |

| Wheat flour | 16 | 16 |

| Oyster shell dust | 2 | 2 |

| Shark oil | 2 | 2 |

| Enteromorphaintestinalis (as a | - | 5 |

| source of natural astaxanthin) |

Table 1: Formulation of experimental diets.

Feeding trial

A feeding trial was run at experimental aquaria for 90 days of duration. Shrimp juveniles were procured from hatchery and stocked in aquaria at a density of 2 individuals/m2. Experimental diets were randomly assigned, the shrimps were fed twice daily and the uneaten feed was checked at regular intervals.

Analysis of astaxanthin content in shrimp muscle tissue

The astaxanthin content was analyzed according to the standard spectrophotometric method [11]. Its value in % was converted to ppm level for easy interpretation of data. The body colouration of shrimps after boiling was compared with Roche SalmoFan™ colour score.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were finally subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All statistical calculations were performed with SPSS 9.0 for Windows.

Results and Discussion

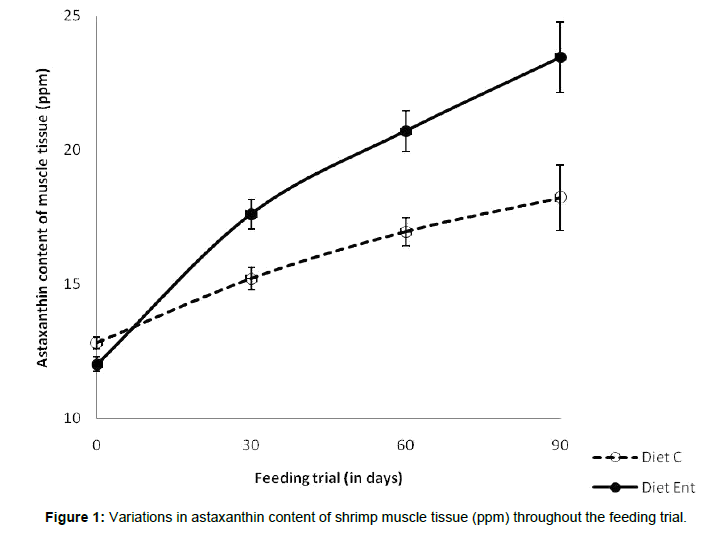

The astaxanthin content in muscle tissue was higher in shrimps fed with Diet ENT as compared to Diet C throughout the feeding trial (Figure 1). A darker orange-red colouration was observed in shrimps fed with Diet ENT after boiling them in water for 5 minutes when compared with Roche SalmoFanTM colour score. The colour score was 30 for Diet ENT fed shrimps whereas a score of 27 was recorded from shrimps fed with Diet C. ANOVA results showed significant variation (p<0.05) in average astaxanthin contents which may be attributed to the capability of P. monodon to easily convert the fraction of seaweed astaxanthin into tissue astaxanthin. The seaweed sample selected for the investigation is found to contain ~120.78 ppm astaxanthin as reported from the present study region [12-14]. Carotenoid, particularly astaxanthin content of feed is one of the major factor influencing the colour development in animals [15] but at the same time scientific knowledge about several factors like dietary pigment source, their dosage level, feeding duration, dietary composition and magnitude of carotenoid esterification is also required to identify these interaction processes [16-20]. The study showed significantly different astaxanthin content of the shrimp species which are in agreement to the observations that crustaceans exhibit strong tendency towards selection of specific carotenoids at a specific rate for their metabolic absorption [16]. Similar work conducted from the present study region reveal that P. monodon when fed with diet containing red algae Catenella repens at a level of 5% improved the body astaxanthin content [21]. The search for natural astaxanthin was not only limited to the seaweed resources, rather salt-marsh grass Porteresia coarctata was also tested as a natural dietary astaxanthin source in P. monodon feed with better results from the present geographical locale [12,22]. In continuation, such natural carotenoid supply to the diet of shrimps has been studied for P. japonicus and Litopenaeus vannamei too from different parts of the globe. The ingredients of natural origin that have been used in the diet are red yeast (Phaffia rhodozyma) and microalgae Dunaliella salina [23]; Chnoospora minima [24]; Spirulina sp. [25,26]; Haematococcus pluvialis [26] and Isochrysis galbana [27]. An usual trend of marked increase in the body carotenoid content has been observed when organisms were fed with plant pigment source diets. For e.g. feed supplemented with 50 ppm algal material (Dunaliella salina) improved the body colouration of P. monodon [28]. Three types of diet when provided to P. semisulcatus containing natural carotenoid sources like red pepper and marigold flower resulted in higher carotenoid accumulation in body tissues [29]. However researchers from Mexico also reported that feed incorporated with cultivated green alga Ulva clathrata significantly improved the body pigmentation of farmed shrimp L. vannamei [30].

Conclusion

Improved product quality of P. monodon clearly reflects the transforming potential of algal astaxanthin into the body tissues by the particular culture species. Thus the present study provides a baseline information about the natural astaxanthin pool of Sundarbans mangrove eco-region which may serve as an alternative to synthetic astaxanthin in animal diets that are much more expensive in terms of costing.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India for providing financial assistance.

References

- Strand A, Herstad O, Liaaen-Jensen S (1998) Fucoxanthin metabolites in egg yolks of laying hens. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 119: 963-974.

- Moss SM (1994) Growth rates, nucleic acid concentrations and RNA/DNA ratios of juvenile white shrimp, Penaeusvannamei Boone, fed different algal diets. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 182: 193-204.

- Penaflorida VD, Golez NV (1996) Use of seaweed meals from KappaphycusalvareziiandGracilariaheterocladaas binders in diets of juvenile shrimpPenaeusmonodon. Aquaculture 143: 393-401.

- Cruz-Suarez LE, Ricque-Marie D, Tapia-Salazar M, Guajardo-Barbosa C (2000) Uso de harina de kelp (Macrocystispyrifera) en alimentosparacamaro´ n, in Avances en Nutricio´nAcui´cola V -Memorias del QuintoSimposiumInternacional de Nutricio´nAcui´cola, Me´rida, Me´xico. Universidad Auto´noma de Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Mexico. p. 227-266

- Rosenberry B (2005) World shrimp farming 2005. Shrimp News International p. 276.

- Howell BK, Matthews AD (1991) The carotenoids of wild and blue disease affected farmed tiger shrimp (Penaeusmonodon, Fabricus). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 98: 375-379.

- Meyers SP (1994) Developments in world aquaculture, feed formulations and role of carotenoids. Pure and Applied Chemistry 66: 1069-1076.

- Britton G, Armitt GMS, Lau YMA, Patel K, Shone CC (1981) Carotenoproteins, in Carotenoid Chemistry and Biochemistry (Pergamon press). Oxford: p. 237-251.

- Lorenz T (1998) A review of the carotenoid astaxanthin as a pigment source and vitamin for cultured Penaeus prawn. NatuRosea Technical Bulletin 51: 1-7.

- Liao IC, Chien YH (1994) Culture of kuruma prawn Penaeusjaponicus in Asia. World Aquaculture 25: 18-33.

- Schuep W, Schierle J (1995) Astaxanthin determination of stabilized, added astaxanthin in fish feeds and pre-mixes, in Carotenoids Isolation and Analysis (BirkhauserVerlag Basel). p. 273-276.

- Mitra A, Ghosh R, Mallik A, Mondal K, Zaman S, Banerjee K (2013) Study on the role of mangrove based astaxanthin in shrimp nutrition, in Sensitivity of Mangrove Ecosystem to Changing Climate (Springer Publishers, India). Springer: p 297-310.

- Banerjee K, Ghosh R, Homechaudhuri S, Mitra A (2009) Biochemical composition of marine macroalgae from Gangetic Delta at the Apex of Bay of Bengal. African Journal of Basic and Applied Science 1: 96-104.

- Chakraborty S, Santra SC (2008) Biochemical composition of eight benthic algae collected from Sunderban. Indian Journal of Marine Sciences 37: 329-332.

- Moretti VM, Mentasti T, Bellagamba F, Luzzana U, Caprino F, et al.(2006) Determination of astaxanthin stereoisomers and colour attributes in flesh of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchusmykiss) as a tool to distinguish the dietary pigmentation source. Journal of Food Additives and Contaminants 23: 1056-1063.

- Meyers SP, Latscha T (1997) Carotenoids, in Crustacean Nutrition, Advances in World Aquaculture (Baton Rouge, LA, USA). p. 164-193.

- Bjerkeng B (2000) Carotenoid pigmentation of salmonid fishes - recent progress, inAdvances en Nutricio´nAcui´cola V -Memorias del QuintoSimposiumInternacional de Nutricio´nAcui´cola, Me´rida, Me´xico, Universidad Auto´noma de Nuevo Leo´ n, Monterrey, Mexico. p. 89.

- Buttle LG, Crampton VO, Williams PD (2001) The effect of feed pigment type on flesh pigment deposition and colour in farmed Atlantic salmon, Salmosalar L. Aquaculture Research 32: 103-111.

- Gomes E, Dias J, Silva P, Valente L, Empis J, et al.(2002) Utilization of natural and synthetic sources of carotenoids in the skin pigmentation of gilthead sea bream (Sparusaurata). Journal of European Food Research Technology 214: 287- 293.

- White DA, Page GI, Swaile J, Moody AJ, Davies SJ (2002) Effect of esterification on the absorption of astaxanthin in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchusmykiss (Walbaum). Aquaculture Research 33: 343-350.

- Banerjee K, Mitra A, Mondal K (2010) Cost-effective and eco-friendly shrimp feed from red seaweed Catenellarepens (Gigartinales: Rhodophyta). Current Biotica 8: 23-43.

- Mitra A, Mondal K, Banerjee K (2011) Effect of salt-marsh grass (Porteresiacoarctata) diet on growth performance of black tiger shrimp,Penaeusmonodon, inDiversification of Aquaculture (Narendra Publishing House, New Delhi), p. 219-232.

- Chien YH, Jeng S (1992) Pigmentation of kuruma prawn Penaeusjaponicus Bate, by various pigment sources and levels and feeding regimes. Aquaculture 102: 333-346.

- Menasveta P, Worawattanamateekul W, Latscha T, Clark JS (1993) Correction of black tiger prawn (PenaeusmonodonFabricus) colouration by astaxanthin. Aquaculture Engineering 12: 203-213.

- Liao WL, Nur-E-Bohran SA, Okada S, Matsui T, Yamaguchi K (1993) Pigmentation of cultured black tiger prawn by feeding with a Spirulina supplemented diet. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 59: 165-169.

- Chien YH, Shiau WC (1998) The effects of Haematococcuspluvialis, Spirulinapacificaand synthetic astaxanthin on the pigmentation, survival, growth andoxygen consumption of kuruma prawn, Penaeusjaponicus Bate, in Book of Abstracts of World Aquaculture '98 Baton Rouge (World Aquaculture Society, LA, USA), p. 156.

- Pan CH, Chen YH, Chen JH (2001) Effects of light regime, algae in water and dietary astaxanthin on pigmentation, growth and survival of black tiger prawn Penaeusmonodonpost-larvae. Zoological Studies 40: 371-382.

- Boonyaratpalin M, Thongrod S, Supamattaya K, Britton G, Schlipalius LE (2001) Effects of ß-carotene source, Dunaliellasalina, and astaxanthin on pigmentation, growth, survival and health of Penaeusmonodon. Aquaculture Research 32: 182-190.

- Gocer M, Yanar M, Kumlu M, Yanar Y (2006) The effects of red pepper, marigold flower and synthetic astaxanthin on pigmentation, growth and proximate composition of Penaeussemisulcatus. Turkish Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences 30: 359-365.

- Cruz-Sua´rez LE, Tapia-Salazar M, Nieto-Lo´pez MG, Guajardo-Barbosa C, Ricque-Marie D (2009) Comparison of Ulvaclathrata and the kelps MacrocystispyriferaandAscophyllumnodosumas ingredients in shrimp feed. AquacultureNutrition 15: 421- 430.

Relevant Topics

- Algal Blooms

- Blue Carbon Sequestration

- Brackish Water

- Catfish

- Coral Bleaching

- Coral Reefs

- Deep Sea Fish

- Deep Sea Mining

- Ichthyoplankton

- Mangrove Ecosystem

- Marine Engineering

- Marine Fisheries

- Marine Mammal Research

- Marine Microbiome Analysis

- Marine Pollution

- Marine Reptiles

- Marine Science

- Ocean Currents

- Photoendosymbiosis

- Reef Biology

- Sea Food

- Sea Grass

- Sea Transportation

- Seaweed

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16456

- [From(publication date):

August-2015 - Apr 01, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11753

- PDF downloads : 4703