Risk Factors to Urinary Tract Infection Related to Prenatal Care in Pregnancy Women Attending Public Care Units of South Brazil

Received: 18-Oct-2018 / Accepted Date: 17-Dec-2018 / Published Date: 24-Dec-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000399

Abstract

Considered as a public health problem, the Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) presents high incidence in pregnant women. Intimate hygiene after sexual relations, environment, body and hand hygiene, hydric ingestion, age and socioeconomic and educational level are some of the predisposing factors to the development of UTI. To identify the pregnant women’s knowledge about the socio-economic and educational level and how these women relate these conditions to the predisposing factors for the development of UTI. This is a transversal study in pregnant women, registered in the Brazilian System of the Follow-up Program of Humanization of Pre-natality and Birth (SispreNatal) in the period from 2015 to 2016. The data were analyzed using the SPSS, version 22 and descriptive statistics such as frequencies, percentages and means were estimated. The Committee of Ethics in Research approved the questionnaire under the process of the University of Santa Catarina State. From the 781 pregnant women included in SispreNatal, 92 (12.5%) accepted to participate in the research, 46 of them belonging to the neighborhood of São Pedro and 46 to the neighborhood Efapi, most of them (n=43, 46.8%) concluded high school. The UTI was present in 47 (51%) of the pregnant women, being more frequent in the neighborhood of São Pedro (n=26, 56.5%). Concerning the preventive orientations of UTI, only 30 (32.6%) pregnant women received some information. From these 30, 11 (36.7%) described the symptomatology as the perception of the infection, considering that 9 (9.7%) related the feminine etiology as a predisposing factor for the development of UTI. Our data met the immediate needs of the health services, but more efficient educational measures in the municipal public politics are suggested, although the identification of predisposing factors is complex.

Keywords: Environment and public health; Primary prevention; Pregnancy; Urinary tract infections

Introduction

The Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) affect approximately 15% of women, mainly in the first trimester of pregnancy [1,2]. Considered as a public health problem, during this gestational period, the UTI has a high incidence due to the anatomical and physiological alterations in the woman, producing reflections over her health and the fetus’s [3-6]. Besides to the increased incidence of symptomatic infections over pregnant women, the therapeutic and prophylactic treatment of antimicrobial can be committed because the toxicity of some drugs is one of the factors that harm the development of the fetus [7]. However, an early clinical diagnosis associated with complementary examinations (qualitative and quantitative of urine and urine culture), during prenatal assistance, provides qualified evidence for an adequate and immediate therapeutic treatment and an excellent maternal and gestational prognosis [8].

The etiologic agents responsible for these UTIs in most of the infections belong to the patient’s microbiota and, due to the use of antimicrobials, bacterial selection, local colonization, fungi and the catheter care can be altered. In this microbiota, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas spp. and Proteus mirabilis are the most frequent and mainly responsible for the infections. Gram-positives are the least frequent agents and among them, there is the Enterococcus [9,10] (Table 1).

| Factors | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Intimate hygiene after sexual relations | It needs to occur from the genital to the anal region before and after sexual intercourse. | Hamdan et al. [11] |

| Sexual frequency | Sexually active pregnant women have a higher risk of UTI. | Law et al. [9] |

| Body and hands hygiene | Body and hands hygiene after physiological needs. | Chenoweth et al. [12] Tadesse et al. [13] |

| Obesity | Obese people are more prone to UTI. | Abdel et al. [14] |

| Immunity | The balanced immune and innate answers reduce the risks of infection for the mother and the fetus. | Nowicket et al. [15] Madan et al. [16] Chaemsaithong et al. [17] |

| Hydric ingestion | Daily intake, minimum 2 L of water, increasing the volume of urine and preventing the fixation of bacteria in the vesicle wall. | Berbel et al. [18] |

| Environment | Public toilets and sinks are sources of bacterial contamination. The absence of basic sanitation conditions determines the human´s health. | Medeiros Jr. et al. [19] Sant’anna et al. [20] |

| Age | Pregnant, anemic, diabetic adolescent women are more likely to develop UTIs | Vettore et al. [21] |

| Socioeconomic and educational level | Pregnant women from a low socioeconomic level, usually black, under 29, nulliparas, start prenatal assistance late. Low schooling contributes to the development of UTI and for asymptomatic infection. | Ennis et al. [22] Jolley et al. [23] Vettore et al. [21] Wing et al. [24] |

| Nutrition | Fruit and vegetables are sources of vitamins and infections. | Emiru et al. [5] |

Table 1: Predisposing factors for the development of UTI according to study analysis.

Urine is sterile and the presence of fungi or bacteria can cause bacteriuria and an infectious process. Also, this risk is increased in populations presenting low socioeconomic and educational levels, being the main risk factor for asymptomatic bacteriuria (BA) [21,23]. In the Brazilian guideline about measures for the prevention of infection related to health assistance (IRAS) published in 2017, it is possible to affirm that, in general, the bacteriuria must not be treated, except in special situations in which the doctor finds treatment relevant. Moreover, the guideline defines that the UTI related to non-catheterrelated health assistance is any symptomatic infection of the urinary tract in a patient without the use of permanent vesical catheter at the moment or for the last 24 h. Regarding this guideline, it is important to mention that there is no prescription for the implantation of simple preventive measures related to pregnant women, not using permanent vesical catheter and/or urine drainage catheter, nor there is a perception of the public politics regarding their morbidity and costs, whether they be expensive or not, of UTIs in pregnant women in relation to other UTIs related to permanent vesical catheter [25].

Furthermore, the predisposing factors to BA include sexual behavior, increase in age, multiparity, individual susceptibility, low socioeconomic and educational level and history of UTIs during childhood [25]. The same predisposing factors can be attributed to cystitis [26]. However, more clarification to the population under social vulnerability may reduce risks of reinfections during pregnancy and postpartum periods [21].

In this sense, the study outlined the socioeconomic and educational level of pregnant women and the way they relate these conditions to the predisposing factors for the development of UTIs in two neighborhoods in Chapeco, in the west of Santa Catarina, Brazil.

Methods

The study was conducted in the neighborhoods Efapi and São Pedro which are located in the city of Chapeco, in the west of Santa Catarina, Brazil. The two neighborhoods were chosen for the development of the research for being geographically opposed in the urban perimeter of the city and for presenting different characteristics of social and economic development. These neighborhoods were opted because Epafi has a large majority of the working class linked to the agroindustrial sector and the São Pedro district linked to the commerce sector. These neighborhoods represent the profile of the workers of the municipality. The two neighborhoods were chosen for the development of the research for being geographically opposed in the urban perimeter of the city and for presenting different characteristics of social and economic development.

This is an observational quantitative research of transversal design, developed from November 2015 to February 2016. There were 781 pregnant women included in the System of the Follow-up Program of Humanization of Pre-natality and Birth (SispreNatal) in the city of Chapecó, SC. The average time for the following-up attributed to each pregnancy was seven months, approximately, because in Brazil the first obstetric consultation of the pregnant women in the public health system occur most of the time from the second month of gestation.

SispreNatal is a Brazilian System of Follow-up Program of Humanization of Pre-natality and Birth that develops actions to promote, prevent and assist the health of pregnant women and newborns with the objective to reduce the high rates of maternal, perinatal and neonatal mortalities. It amplifies the access, the covering and the quality of prenatal follow-up, from assistance to birth and postpartum as well as neonatal assistance, subsidizing cities, states and the federal district with important information for the planning, follow-up and evaluation of developed actions, via Program of Humanization of Pre-natality and Birth.

During the survey, the Epapi Ward had 48 pregnant women registered and in Sao Pedro, there were 46 pregnant women, total 94. The sample was the entire population of pregnant women in these two districts registered in Sispre Natal. Except for two Haitian immigrants in the Efapi neighborhood, who refused to sign the ethical terms of the survey, the others agreed to participate. Considering that the two districts represent cultural, social and economic similarity of the other districts of the studied municipality, the sampling was satisfactory to meet the research objectives. This is because the municipality has the same education and health management system in its territory.

The interview had questions about prenatal care data using the Unified Health System (SUS) that covered the identification of each pregnant woman (age, level of education, marital status, paid job, number of previous pregnancies, obstetric history, diabetes, anemia, preterm birth history), the laboratory tests collected and their results and, finally, about the therapy used to confirm UTI. This prenatal care is performed by a multi-professional team and the doctor is responsible for requesting tests to diagnose and treat UTI.

Data source and data collection

Each Center of Health of the participating family is constituted by three teams of the Family Health Strategy. As an inclusion criterion in the study, the registered users in the Prenatal SUS with their first prenatal consultation from November 2015 to February 29th, 2016 were adopted as well as free will to participate in the research through signing the Free and Clarified Consent Term. A questionnaire with a pre-established script was applied to the pregnant women, which approached issues about their sociodemographic conditions and their knowledge about the UTIs. The interview was carried out in the health units of the two neighborhoods where the consultations were carried out by the multi-professional team.

The questionnaire reliability was defined through the elaboration of questions to meet the central objective of the research. The questionnaire had internal consistency so the answer of one question did not influence other answer.

Statistical analysis and ethical aspects

The data collected were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 22). Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, percentages and means, were used to analyze the result. This study was approved by Research Ethics Committee of Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, respecting the ethical issues recommended in Resolution 466/2012 from the National Council of Health, Ministry of Brazilian Health.

Results

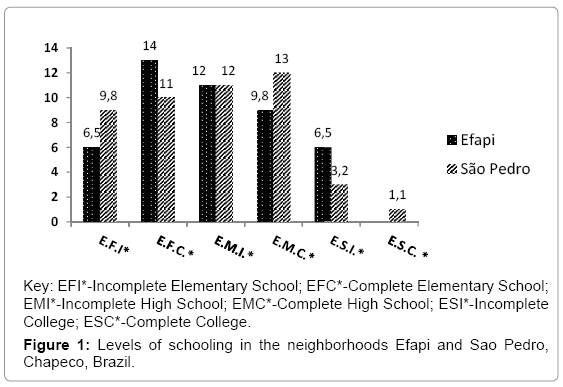

Of 781 pregnant women included in the Pre-Natal and Birth Humanization Program Monitoring System (SispreNatal) in the municipality of Chapeco, SC, there were 92 (12.5%) who accepted to participate in the study, 46 were from São Pedro neighborhood and 46 from Efapi neighborhood. From 92 pregnant women interviewed, most of them went High School 221(n=43, 46.8%). Only one pregnant woman did not answer the question. The National Brazilian Common Curricular Basis (BNCC) characterizes essential part of learning for the student of elementary school (from the first to the ninth year) and for the student of high school (from the first to the third year) specific and pedagogical items of education in relation to Arts and Sciences (Portuguese language, English language, Physical Education, Math, Geography, History, Arts, Sciences) [27]. Thus, the pregnant women from the Efapi neighborhood presented a higher level of complete elementary school (9 years of study). On the other side, the pregnant women of the neighborhood of Sao Pedro were characterized for presenting a higher index for high school (three complete years) and one of them had finished college at the date of the research (Figure 1).

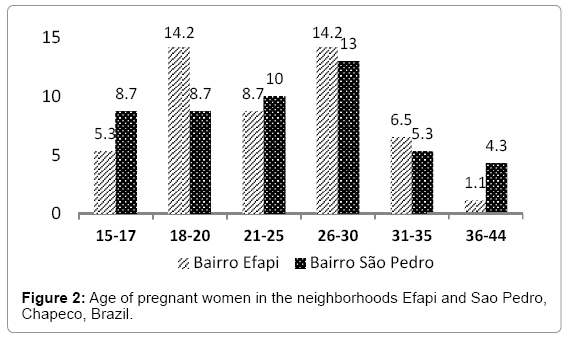

The highlighted data in the two neighborhoods indicate low socioeconomic index, being a result of low education level and a high number of young pregnant women. Regarding their age, 13 (14%) pregnant women belong to the group aged 15 to 17 and 21 (22.8%) to the group aged 18 to 20 years old. In these two groups, the frequency of UTI was above 62% (Figure 2).

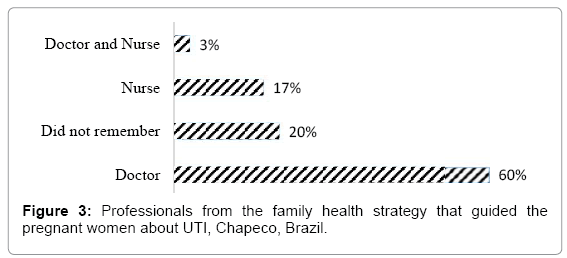

From 92 pregnant women, 47 (51%) developed some UTI during pregnancy, being more frequent in the neighborhood of São Pedro (n=26, 56.5%). As for the information and/or orientations from the health team on UTIs, the pregnant women, only 30 (32.6%) received some kind of information. And 18 of them (60.0%) received medical orientation, 5 (17.0%) from nurses, 1 (3.0%) from doctors and nurses and 6 (20.0%) did not remember who professional guided them (Figure 3).

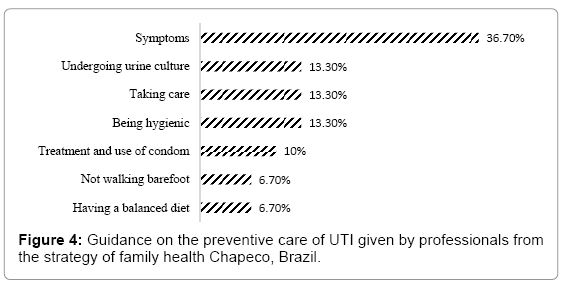

From these 30 (32.6%) pregnant women who were interviewed on the information received about preventive care of UTI, 11 (36.7%) described the symptomology as perception of the infection 9 of them (9.7%) made a relation between the etiology of the infection and the feminine anatomy as predisposing factors for the development of UTI and 18 pregnant women (18.4%) did not know how to answer. There were 75% (66) who argued with factors, 45.4% (40) of Efapi neighborhood and 29.4% (26) of Sao Pedro neighborhood (Figure 4).

Regarding the predisposing factors to UTI, 44 (47%) pregnant women mentioned microorganisms, sexual habits, personal and intimate hygiene, diet quality, pregnancy, immunity, environment cleaning, water, smoking, walking barefoot, according to their level of education, shown in Table 2.

| Level of schooling of the pregnant women (n%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | EFI | EFC | EMI | EMC | ESI | ESC | TOTAL (N=45) |

| Microorganisms | - | - | - | - | 2.2% | - | 4.5% |

| Sexual habits | 2.2% | - | 6.7% | 6.7% | 2.2% | - | 17.8% |

| Personal hygiene | - | 4.5% | - | 2.2% | 2.2% | - | 8.9% |

| Diet | 2.2% | 4.5% | 4.5% | - | - | 11.1% | |

| Immunity | - | 2.2% | - | - | 2.2 % | - | 4.5% |

| Gestational factors | - | - | - | 2.2% | - | - | 2.2% |

| Contaminated water | - | - | 2.2% | - | - | 2.2% | 4.5% |

| Environment cleaning | - | 2.2% | - | - | - | - | 2.2% |

| Walking barefoot | 4.5% | 20% | 4.5% | 6.7% | 6.7% | - | 42% |

| Total | 11.4% | 32% | 22.7% | 18% | 13.6% | 9% | - |

Key: EFI-Incomplete Elementary School; FFC-Complete Elementary School; EMIIncomplete High School; EMC-Complete High School; ESI-Incomplete College; ESC-Complete College.

Table 2: Predisposing factors to UTI and level of education of the pregnant women.

Discussion

Although historically, the two neighborhoods had their origins in different socioeconomic contexts, the results slightly differed in relation to the pregnant women’s knowledge about the predisposing factors for the development of UTI and about preventive strategies for such an infection. It was also observed that among the neighborhoods studied, the level of education was not the decisive factor for the effectiveness of the pregnant women’s self-care once the weaknesses of the learning process reflect the low quality of the Brazilian public educational system. Our findings show that the educational level of pregnant women in both neighborhoods is between Elementary School (41.3%) and High School (46.8%) and when associated with UTI risk, the sexual activity, the cultural environment (walking barefoot) and personal hygiene were mainly found. In a cross-sectional study conducted in Brazil, UTI risk factors in 1,005 pregnant women were evaluated, where 501 with UTI and 590 without UTI and a higher frequency of younger pregnant women (65%, 20 to 34 years old) with UTI, an educational level (>8 years) in 52.7% pregnant women with UTI and 71.7% of them were living with a partner [21]. When it was associated with the management of urinary tract infection in the prenatal SUS with the profile of the pregnant women, there was an inadequacy in the management of care in the history of prematurity, neonatal mortality, number of previous pregnancies, pre-pregnancy nutritional status, anemia and diabetes [21]. This inadequacy in management suggests that it is difficult for healthcare professionals to communicate with pregnant women and understand the guidelines or information about their obstetric clinic and infection. With this incomprehension, there is a non-adherence to the clinical follow-up in the treatment of UTI.

This quantitative data about low education level is a determiner of social risk in populations with low socioeconomic level and women without information on the importance of prenatal assistance have higher risks to develop gestational complications, especially teenage pregnant women [21,28]. The low education level verified in the interviewed population reflects, indirectly, the social economic conditions [21-24] and, its immediate reflex is the high index of pregnancy in low age categories. Females with this profile firstly opt for constituting a family instead of a social and economic stability. In this way, unprepared for work and presenting little understanding of factors can make them vulnerable to infections increase the scenery aggravated by risks concerning UTI. A study analyzed 2.188 (5.7%) puerperal women that presented UTI during pregnancy and when relating the variable UTI to education and familiar income found out that there was a smaller proportion of infection among pregnant women with higher level of education (p=0.002) and higher familiar income (p<0.001) [29].

There were 367 pregnant women evaluated on UTI risk factors in North West Ethiopia and the gestational age (second semester, p=0.251=0.558, third semester, p=0.287=0.596), multiparity, (multiparous, p=0.717=1.181, primiparous, p=0.134=0.536) and educational level (variation among illiterate women who can read and write to those with higher education) were not clinically significant with the infection [5]. However, the association between sexual activity (p=0.0032=3.5), maternal anemia (p=0.003=3.377) and family monthly income (<$37.85 and $37.85 to $75.70) (p=0.006, 0.039 respectively) with UTI, there was clinical significance. This study showed an association of UTIs between symptomatic pregnant women (>105CFC/mL and clinical symptoms) and asymptomatic (presence of two consecutive urine specimens of the same uropathogenic, without urinary symptoms). In another study, the prevalence of UTI among pregnant women (gestational age 29 weeks) was 14% (n=235) regardless of the woman's age, gestational age and multiresistance to the antibiotic of the microorganism found (E. coli). This shows the similarity of studies conducted on the African continent, however, the search for information for the factors related to UTI in the pregnant women is not elucidated, since each country has the clinical guidelines of health public services [11].

Regardless the answers, relating the infections with the microorganisms (2.2%), gestational cycle (2.2%), intimate hygiene (8.9%), diets (11.1%), immunity, contaminated water (4.5%), clean environment (2.2%) and walking barefoot (42%), the following considerations are shown: 1) Only 44 of the 92 interviewed (47%) risked to answer this question. Regarding the others who did not know or did not want to answer had low education or did not receive any information at the health service during the prenatal medical visit. In this context, low education level becomes a risk factor, which makes the pregnant woman vulnerable. The level of education influences the understanding of the explanations provided by health professionals about the emergence and control of infections. Understanding that pregnant women are predisposed because of anatomical and physiological factors, other care, such as intimate hygiene, is more carefully observed [11,17]. However, the answers such as contaminated water can cause UTI should not be disregarded since the pregnant woman may have a colonization of uropathogenic enterobacteria due to the ingestion of contaminated water. Although the two districts had treated water for the population, the development of UTIs in this population is not justified. 2) Regarding certain myths, such as relating the appearance of UTI to walking barefoot, as stated by 42% of our pregnant women, there is no scientific evidence that walking barefoot increases the risk for the development of UTI. However, in small proportions, this can be applied to recurrent infections. In these cases, there is recurrence when bacteria infect the epithelium and remain there, resurfacing when the immune system becomes compromised. Consequently, there is the resurgence of symptoms, especially in pregnant women who are in a vulnerable group [30]. 3) However, the answers has sense in many contexts, such as the infections to the microorganisms of the microbiota of each individual as a risk factor. The contamination of faucets in public toilets was highlighted as one of the sources of dissemination of pathogenic bacteria, such as Escherichia coli. In Brazil, most faucets in public spaces are threaded and manually operated and the ideal is pressure. Thread taps require increased hand exposure and consequently increase contamination [19].

Although the development of UTI may occur for multiple factors, none of the answers given by the pregnant women, such as walking barefoot, taking rain showers and getting cold, should be discarded. According to some experts, it is possible to affirm that information such as the ones identified in the research, such as walking barefoot, need to be evaluated in a group involving the other predisposing factors [31]. It is important to highlight the influence of cold in the musculature to explain that walking barefoot is a risk factor to UTI, increasing the urinary frequency and interfering with the adaptive immunological system thus making the individual susceptible to infections.

The orientations given by the health professionals, such as taking care of one’s diet, not walking barefoot, use of condom, intimate bodily daily hygiene, adequate ingestion of water, quitting smoking, routine examinations (urine culture), need to be analyzed in a broader context because our findings were solely built on symptoms, that is, centered on the prevention instead of health promotion. Besides, some orientations such as the hydric ingestion were not rigorously followed so much that 32 (35%) affirmed to have drunk <900 mL of water/day when the recommended ingestion would be 2 L/day [18].

Face to the previously presented elements, all the interviewees (100%) demonstrated having meager perception and comprehension of the predisposing factors to UTI. This gap for knowledge favors the risks of expositions to infections, hindering, in this way, the identification of the causes and the adoption of effective strategies to promote and prevent infections related to the urinary tract.

Conclusion

Although our study had limitations in the data analysis by failing to associate the profile of those interviewed who did not answer some questions regarding their level of education, it is unanimously affirmed that both the Brazilian education system and the public health system are not being able to attend some of their basic skills. It is generally perceived that pregnant women cannot internalize the information received in the health services although they have a moderate level of education (elementary school), which, consequently, places them in a group at risk in the face of vulnerabilities. For this reason, it is the responsibility of the health system to evaluate the management strategies of this population.

Limitations and Recommendation

The study presented some limiting factors such as the absence of primary sources for the identification of the pregnant women’s knowledge about the predisposing factors to infections (school, health professional orientation, media or everyday life) and also the noncharacterization of the level of incomplete education such as in progress or drop out.

Although the identification of predisposing factors to UTI is complex, either for health professionals or for the population, our data met the immediate needs of the health services suggesting, in this way, more efficient educative measures of the city’s public policies. It was also observed the necessity for bigger investments in the qualification of the health professionals to provide adequate assistance to pregnant women since they are users of the Brazilian health services. Nevertheless, the ideal orientation would be to subsidize this population with the knowledge to promote health instead of generic information about prevention and treatment. The way the orientations are presented, they do not enlarge the perception of the pregnant women about the risks of UTI.

Acknowledgment

This study was conducted in total fulfillment of the requirements at the State University of Santa Catarina, Brazil.

References

- Duarte G, Marcolin AC, Quintana SM, Cavalli RC (2008) Urinary tract infection in pregnancy. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 30(2): 93-100.

- Nogueira NAP, Moreira MAA (2006) Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women of the Centro de Saúde Ambulatorial Abdoral Machado, Crateus-CE. Rev Bras Anal Clin 38: 19-21.

- Nascimento WLS, Oliveira FM, Araujo GLS (2012) Urinary tract infection in pregnant women who use the single health system. Ensaios e Ciência: Ciências Biológicas, Agrárias e da Saúde 16: 111-123.

- Calegari SS, Konopka CK, Balestrin B, Hoffmann MS, Souza FS, et al. (2012) Results of two treatment regimens for pyelonephritis during pregnancy and correlation with pregnancy outcome. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet34: 369-375.

- Emiru T, Beyene G, Tsegaye W, Melaku S (2013)Associated risk factors of urinary tract infection among pregnant women at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar, North West Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 25: 292.

- Farkash E, Weintraub AY, Sergienko R, Wiznitzer A, Zlotnik A, et al. (2012)Acute antepartum pyelonephritis in pregnancy: A critical analysis of risk factors and outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 162: 24-27.

- Leekha S, Terrell CL, Edson RS (2011) General principles of antimicrobial therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 86: 156-167.

- Baumgarten MCS, Silva VG, Mastalirb FP, Klausb F, d’Azevedoc PA (2011) Urinary tract infection in pregnancy: Review of literature. UNOPAR Cient Cienc Biol Saúde 13: 333-342.

- Law H, Fiadjoe P (2012) Urogynaecological problems in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 32: 109-112.

- Reyes-Hurtado A, Gomez-rios A, Rodriguez-Ortiz JA (2013) Validity of partial urine and gramen diagnosis of urinary tract infection in pregnancy. Hospital Simón BolÃvar, Bogotá, Colombia, 2009-2010. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol 64: 53-59.

- Hamdan HZ, Ziad AH, Ali SK, Adam I (2011) Epidemiology of urinary tract infections and antibiotics sensitivity among pregnant women at Khartoum North Hospital. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 18: 2.

- Chenoweth CE, Gould CV, Saint S (2014)Diagnosis, management and prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 28: 105-119.

- Tadesse E, Teshome M, Merid Y, Kibret B, Shimelis T (2014) Asymptomatic urinary tract infection among pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic of Hawassa Referral Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 17: 155

- Abdel MP, Ast MP, Lee YY, Lyman S, Valle AGD (2014) All-cause in-hospital complications and urinary tract infections increased in obese patients undergoing total Knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 29: 1430-1334.

- Nowicki B, Sledzinska A, Samet A, Nowicki S (2011) Pathogenesis of gestational urinary tract infection: Urinary obstruction versus immune adaptation and microbial virulence. BJOG 118: 109-112.

- Madan I, Than NG, Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, Miranda J, et al. (2014)The peripheral whole-blood transcriptome of acute pyelonephritis in human pregnancya. J Perinat Med 42: 31-53.

- Chaemsaithong P, Romero R, Korzeniewski SJ, Schwartz AG, Stampalija T, et al. (2013)Soluble trail in normal pregnancy and acute pyelonephritis: A potential explanation for the susceptibility of pregnant women to microbial products and infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 26: 1568-1575.

- Berbel LAS, Gural NRG, Schirr F (2011) Nursing guidelines for prenatal for the prevention of urinary tract infection. Revista Eletrônica da Faculdade Evangélica do Paraná FEPAR 1: 13-22.

- Medeiros MC, Silveira GS, Pereira JBB, Chavasco JM, Chavasco JK (2012)Verification of nature of fecal contaminants in Surface of public bathroom taps. Rev UNICOR 10: 297-303.

- Sant’anna, CF, Cezar-Vaz MR, Cardoso LS, Erdmann AL, Soares JFS (2010) Social determinants of health: Community features and nurse work in the family health care. Rev Gaucha Enferm 31: 92-99.

- Vettore MV, Dias M, Vettore MV, Leal MC (2013) Evaluation of the management of prenatal urinary tract infection in pregnant women of the Unified Health System in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Rev Bras Epidemiol 16: 338-351.

- Ennis M, Callaway L, Lust K (2011) Adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the management of pyelonephritis in pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 51: 505-509.

- Jolley JA, Kim S, Wing DA (2012) Acute pyelonephritis and associated complications during pregnancy in 2006 in US hospitals. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 25: 2494-2498.

- Wing DA, Fassett MJ, Getahun D (2014) Acute pyelonephritis in pregnancy: An 18-year retrospective analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 210: 219.e1-6.

- Matuszkiewicz-Rowińska J, Małyszko J, Wieliczko M (2015) Urinary tract infections in pregnancy: Old and new unresolved diagnostic and therapeutic problems. Arch Med Sci 11: 67-77.

- Kamgang F. de P.S, Maise H.C & Moodley J (2016) Pregnant women admitted with urinary tract infections to a public sector hospital in South Africa: Are there lessons to learn? South Afr J Infect Dis 31: 79-83.

- Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC) (2016) Proposta preliminar. 2nd edition. Ministério da Educação, BrasÃlia, pp.396.

- Hackenhaar AA, Albernaz AP (2013) Prevalence and associated factors with hospitalization for treatment of urinary tract infection during pregnancy. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 35: 199-204.

- Bánhidy F, Acs N, Puhó EH, Czeizel AE (2007) Pregnancy complications and birth outcomes of pregnant women with urinary tract infections and related drug treatments. Scand J Infect Dis 39: 390-397.

- Khasriya R, Sathiananthamoorthy S, Ismail S, Kelsey M, Wilson M, et al. (2013) Spectrum of bacterial colonization associated with urothelial cells from patients with chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. J Clin Microbiol 51: 2054-2062.

- Stefanello J, Nakano AMS, Gomes FA (2008) Beliefs and taboos related to the care after delivery: Their meaning for a women group. Acta Paul Enferm 21: 275-281.

Citation: Korb A, Barimacker SV, dos Santos MST, Fincatto S, Vendruscolo C, et al. (2018) Risk Factors to Urinary Tract Infection Related to Prenatal Care in Pregnancy Women Attending Public Care Units of South Brazil. J Preg Child Health 5:399. DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000399

Copyright: © 2018 Korb A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 6643

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Dec 02, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 5468

- PDF downloads: 1175