Review on Ebola Virus Disease: Its Outbreak and Current Status

Received: 03-Oct-2015 / Accepted Date: 23-Oct-2015 / Published Date: 25-Oct-2015 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000204

Abstract

Background: Ebola virus disease (EVD) is caused by Ebola viruses (EBOV), members of the group of hemorrhagic fevers and it is one of the most dangerous infection diseases with mortality rates up to 90%. Ebola was firstly described in 1976 and since then occurred sporadically in Central Africa. Till 2014, twenty four outbreaks were described, but the number of deaths not exceeding 300 per outbreak. As of May 20, 2015 the cumulative number, suspected, and laboratory-confirmed cases attributed to Ebola virus was 26, 969, including 11,135 deaths. Pathogenesis: Ebola Viruses do not replicate through cell division, but instead insert their own genetic sequencing into the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of the host cell and subsequently hijack all cellular processes, including transcription and translation. In essence, the host cell becomes a factory of viral proteins. As new viral capsules are formed, they bud from the host cell, taking a part of the host cell’s outer membrane, thus cloaking themselves against detection by the host’s immune system. In some cases, the patient’s immune system can produce enough antibodies to defeat the infection. With EVD, the virus can often reproduce so rapidly that the immune system never catches up. Transmission: The natural reservoir of EBOV is believed to be bats, particularly fruit bats, and it is primarily transmitted between humans and from animals to humans through body fluids. Clinical presentation: Symptoms of EVD include abrupt onset of fever, myalgias, and headache in the early phase, followed by vomiting, diarrhea and possible progression to hemorrhagic rash, life-threatening bleeding, and multi organ failure in the later phase. Treatment: There are no approved treatments or vaccines available for EVD until today; the mainstay of therapy is supportive care. However, there are a bunch of therapeutic approaches on the track which could have the real impact on control and prevention of this global threat. High fatality, combined with the absence of treatment and vaccination options, makes Ebola virus an important public health pathogen and biothreat pathogen of category A.

Keywords: Ebola virus disease; Hemorrhagic fever; Outbreak; Supportive care; Reservoir; West Africa

163210Abbreviations

ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase. AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; BDBV: Bundibugyo Ebola virus; CDC: Center for Disease and Prevention; DIC: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid; DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo; EBOV: Ebola virus; EHF: Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever; ELISA: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; EVD: Ebola Virus Disease; GP: Glycoprotein; HCWs: Health Care Workers; IL: Interleukin; MAbs: Monoclonal Antibody; NGO: Non-Governmental Organization; NHPs: Non- Human Primates; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; PPE: Personal protective equipment; RNA: Ribonucleic acid; RESTV Reston Ebola Virus; SUDV: Sudan Ebola Virus; TAFV: Tai Forest Ebola Virus; UNCEF United Nation Children Fund; UK: United Kingdom; US: United States; WAEO West Africa Ebola Outbreak ; WHO: World Health Organization; ZEBOV: Zaire Ebola Virus.

Introduction

Background

Ebola virus disease (formerly called Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever) is a severe, often fatal, disease in humans and nonhuman primates, which is caused by the Ebola virus. Between 1976 and 2014 twenty-four epidemics of Ebola virus disease (EVD) were verified, mostly caused by Zaire Ebola virus (ZEBOV) in Equatorial Africa. Most outbreaks have been small, but the virus captured the attention of the world due to death rates that can be as high as 90% as well as the visceral manner in which it kills [1-3].

In March 2014, World Health Organization (WHO) reported a major Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, western African nations. The 2014 EVD outbreak in West Africa caused by ZEBOV is the longest, largest, deadliest, and the most complex in history. As of 11 February 2015, there were 22,859 EVD cases and a total of 9,162 deaths. Compared to the cumulative sum of past episodes in 36 years (1976-2012), 2,232 infected people and 1,503 deaths there are now over ten times the total number infection cases and over six times the total number of fatalities [1,4,5]. The Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa affected impoverished post-conflict countries with weak health systems and no experience with Ebola. [6].

Ebola is a public health nightmare because it can be contacted relatively easily (especially in a hospital setting where proper precautions are not taken) and is almost always fatal. EVD can be transmitted between humans through direct contact with bodily fluids (e.g., blood, sweat) from an infected person or contaminated objects. Whereas aerosol infection has not been reported clinically, despite it has been demonstrated in experimental infection in monkeys [7,8]. One of the reasons that Ebola is so dangerous that its symptoms are varied and appear quickly, yet resemble those of other viruses so much that the hemorrhagic fever is not rapidly diagnosed [2]. The current outbreak gives an opportunity to evaluate vaccine efficacy, safety and there is an acute need for a vaccine [9].

Most studies recommended that, the best chance for survival once infected is early diagnosis followed by comprehensive supportive care. While diagnostic tests exist, they often result in false negatives in those who have recently begun to experience symptoms, so isolation and retesting is often the best course of action [10].

Classification

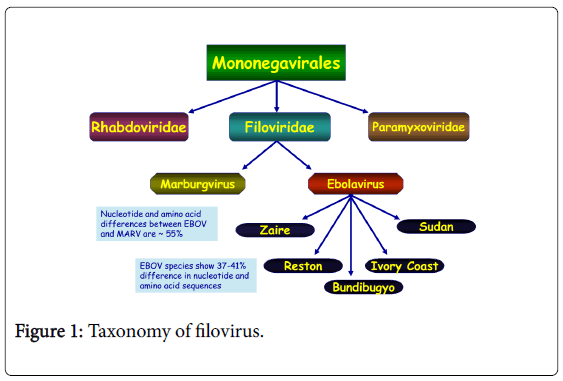

Ebola virus, formerly designated Zaire Ebola virus is one of five known viruses within the genus Ebola virus, family filoviridae, and order mononegavirales [11,12].

Filovirus outbreak is one of the most fatal viral diseases worldwide affecting humans and nonhuman primates (NHPs) and therefore, EBOV is identified as a bio-safety level 4 pathogens and CDC category A agents of bioterrorism [13] (Figure 1).

Outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease

Ebola outbreaks between 1976 and 2014, adapted from WHO are given in Table 1.

| Year | Country | EboV subtype | Number of human cases | Number of deaths | Mortality | Source and spread of infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village | ||||||

| 1976 | Sudan, Nzara and Marida | Sudan virus | 284 | 151 | 53% | Spread by close contact within hospitals, many hospital staff were infected |

| 1976 | Zaire, Yambuku | Ebola virus | 318 | 280 | 88% | Contaminated needles and syringes in hospitals |

| 1976 | England | Sudan virus | 1 | 0 | Laboratory infection, accident-stick of contaminated needles | |

| 1977 | Zaire, Tandala | Sudan virus | 1 | 1 | 100% | Noted retrospectively |

| 1979 | Sudan, Nzara and Marida | Sudan virus | 34 | 22 | 65% | Recurrent outbreak at the same site as the 1976 |

| 1989 | USA, Viriginia, and Pennsylvania | Restone virus | 0 | 0 | EboV was introduced in to quarantine facility by monkeys from the Philippines | |

| 1989-1990 | Philippines | Restone virus | 3 | 0 | Source: macaques from USA. Three workers (animal facility) developed antibodies, did not get sick | |

| 1990 | USA, Viriginia | 4 | 0 | The same to 1989 | ||

| 1994 | Gabon | Ebola virus | 52 | 31 | 60% | Initially thought to be yellow fever, identified as Ebola in 1995 |

| 1994 | Cote d’Ivoire | Tai Forest virus | 1 | 0 | Scientist become ill after autopsy on a wild chimpanzee (Tai Forest) | |

| 1995 | Democratic Republic of Congo (Zaire | Ebola virus | 315 | 250 | 81% | Case-patient worked in the forest, spread through families and hospitals |

| 1996 | Gabon | Ebola virus | 37 | 21 | 57% | Chimpanzee found dead in the forest was eaten by hunters, spread in family members |

| 1996-1997 | Gabon | Ebola virus | Case-patient was a hunter from forest camp, spread by cloth contact | |||

| 1996 | South Africa | Ebola virus | 2 | 1 | 50% | Infected medical professional traveled |

| 1996 | Russia | Ebola virus | 1 | 1 | 100% | Laboratory contamination |

| 2000-2001 | Uganda | Sudan virus | 425 | 224 | 53% | Providing medical care to Ebola case-patient without using adequate personal protective measures |

| 2001-2002 | Gabon | Ebola virus | 65 | 53 | 82% | Outbreak occurred over border of Gabon and Republic of Congo |

| 2001-2002 | Republic of the Congo | Ebola virus | 57 | 43 | 75% | Outbreak occurred over border of Gabon and Republic of the Congo |

| 2002-2003 | Republic of the Congo | Ebola virus | 143 | 128 | 89% | Outbreak in the districts of Mbomo and kelle in Cuvette Ouest Department |

| 2003 | Republic of the Congo | Ebola virus | 35 | 29 | 83% | Outbreak in villages located in Mbomo district, Cuvette Ouest Department |

| 2004 | Sudan, Yambio | Sudan virus | 17 | 7 | 41% | Outbreak concurrent with an outbreak of measles, and several cases were later reclassified as measles |

| 2004 | Russia | Ebola virus | 1 | 1 | 100% | Laboratory infection |

| 2007 | Democratc republic of the Congo | Ebola virus | 264 | 187 | 71% | The outbreak was declared over November 20. Last death on October 10 |

| 2007-2008 | Uganda | Bundibugyo virus | 149 | 37 | 25% | First reported occurrence of a new strain |

| 2008 | Philippines | Reston virus | 6 | 0% | Six workers (pig farm) developed antibodies, did not become ill | |

| 2008-2009 | Democratic republic of the Congo | Ebola virus | 32 | 15 | 47% | Not well identified |

| 2011 | Uganda | Sudan virus | 1 | 1 | 100% | The Uganda Ministry of Health informed the public a patient with suspected Ebola died on May 6, 2011 |

| 2012 | Uganda, Kibaale | Sudan | 11 | 4 | 36% | Laboratory tests of blood samples were conducted by the UVRI and the CDC |

| 2012 | Democratic republic of the Congo | Bundibugyo virus | 36 | 13 | 36% | This outbreak had no link to the contemporaneous Ebola outbreak in the kibaale, Uganda |

| 2012-2013 | Uganda | Sudan virus | 6 | 3 | 50% | CDC assisted the ministry of Health in the epidemiology and diagnosis of the outbreak |

| 2014 | Democratic republic of the Congo | Zaire virus | 66 | 49 | 74% | The outbreak was unrelated to the outbreak of West Africa |

Figure 4: Completed facial reconstruction (half-profile, plasticine).

West Africa outbreaks

Ebola virus disease cases West Africa outbreak were given in Table 2.

| Country | All cases | Health care workers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | |

| Guinea | 3548 | 2346 | 187 | 94 |

| Sierra Leone | 12,206 | 3857 | 303 | 221 |

| Liberia | 10,042 | 4486 | 374 | 188 |

| Total | 25,791 | 10,689 | 864 | 503 |

Table 2: Ebola Virus Disease cases West Africa outbreak at 12/4/15 [15].

Virology and Pathogenesis

The genome of Ebola virus is 18,959 nucleotides in length and 80 nanometers (nm) in width containing only seven Open Reading Frames (ORFs). Despite limited encoding capacity, this virus expands its gene functions by forming more proteins and assigning more functions to each of them. Nine proteins have been known to be translated, including nucleoprotein (NP), the polymerase cofactor viral protein (VP35), the major matrix protein (VP40), glycoprotein (GP), soluble glycoprotein (sGP), small soluble glycoprotein (ssGP), transcription activator (VP30), the minor matrix protein (VP24), and viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L). The GP, a surface protein inserted into the viral membrane, functions during virus entry into the host cells by binding to its receptor and fusion with cell membrane [16].

Viral genes including 3’-UTR (un translated regions)-NP-VP35- VP40-GP-VP30-VP24-L-5’-UTR, that are transcribed by the viral RNA dependent RNA Polymerase present in the virion. The single strand of RNA is covered by helically arranged viral nucleoproteins NP and VP30, which are linked by matrix proteins VP24 and VP40 to the lipid bilayer that coats the virion [17]. Viral protein 35 (VP35), encoded by filoviruses, is a multifunctional dsRNA binding protein that plays important roles in viral replication, innate immune evasion, and pathogenesis. The multifunctional nature of these proteins also presents opportunities to develop countermeasures that target distinct functional regions. The EBOV matrix protein is VP40, which is also found localized under the lipid envelope of the virus where it bridges the viral lipid envelope and nucleocapsid. The VP40 is effectively a peripheral protein that mediates the plasma membrane binding and budding of the virus prior to egress. The Ebola virus structural glycoprotein (known as GP 1, 2) is responsible for the virus’ ability to bind to and infect targeted cells. The viral RNA polymerase encoded by the L gene, partially uncoated the nucleocapsid and transcribes the genes into positive-strand mRNAs, which are then translated into structural and nonstructural proteins [13,16].

Pathogenesis

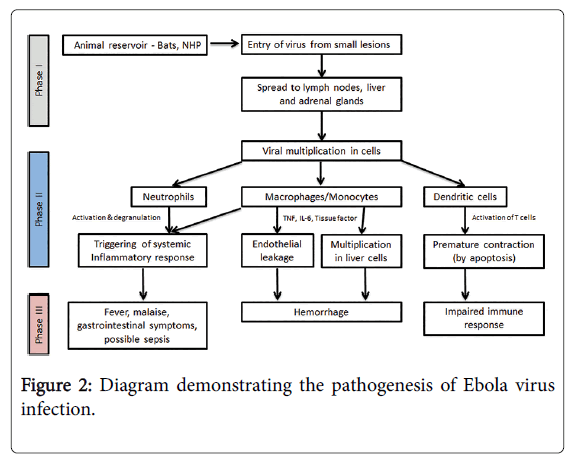

The path physiology of Ebola is not yet fully understood, however, most studies report that the incubation period varies depending on the type of exposure (i.e., six days for percutaneous and ten days for contact exposure). The WHO Ebola response team’s findings have documented that the mean incubation period was 11.4 days, which did not vary by country. Following viral transmission, symptoms usually appear in approximately eight to ten days (range, 2-21 days). Because of the difficulty of performing clinical studies under outbreak conditions, almost all data on the pathogenesis of Ebola virus disease have been obtained from laboratory experiments employing mice, guinea pigs, and nonhuman primates. However, case reports and largescale observational studies of patients in the 2014-2015 West Africa outbreaks are providing urgently needed data on the pathogenesis of the disease in humans [18,19] (Figure 2).

Phase I can be characterized as the transfer of EBOV from an animal carrying the virus to a human, usually via small cutaneous lesions. Similar principles apply in human-to-human transmission during Ebola outbreaks. Phase II can be characterized as the early symptomatic stage - usually between days four and ten - where symptoms of a viral illness appear and gradually progress toward more advanced manifestations of the disease. Finally, Phase III represents the advanced Ebola virus disease, with hemorrhagic manifestations, impaired immunity, and end-organ failure. Adapted from Journal of Global Infectious Diseases/Oct-Dec 2014/Vol-6/Issue-4. NHP: Nonhuman Primate; TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor; IL: Interleukin

Cell entry and tissue damage

After entering the body through mucous membranes, breaks in the skin, or parentally, Ebola virus infects many different cell types. Macrophages and dendrite cells are probably the first to be infected; filoviruses replicate readily within these ubiquitous’’ sentinel’’ cells, causing their necrosis and releasing large numbers of new viral particles into extracellular fluid [13,20]. Rapid systemic spread is aided by virus-induced suppression of type l interferon responses. Dissemination to regional lymph nodes results in further rounds of replication, followed by spread through the bloodstream to dendrite cells and fixed and mobile macrophages in the liver, spleen, thymus, and other lymphoid tissues. Necropsies of infected animals have shown that many cell types (except for lymphocytes and neurons) may be infected, including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, hepatocytes, adrenal cortical cells, and epithelial cells. Fatal infection is characterized by multifocal necrosis in tissues such as the liver and spleen [21]. And resulted Impairment of adaptive immunity, Coagulation defect, Systemic inflammatory response, gastrointestinal dysfunction

Viral Reservoirs and Mode of Transmission

Viral reservoirs

The natural reservoir for Ebola has not identified until today; however, bats are considered to the most likely candidate species. Three types of fruit bats (Hypsignathus monstrous, Epomops franqueti and Myonycteris torquata) were found to possibly carry the virus without getting sick [2]. Bats were known to roots in the cotton factory in which the first cases of the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks were observed, and they have also been implicated in Marburg virus infection in 1975 and 1980. Of 24 plant and 19 vertebrate species experimentally inoculated with EBOV, only bats displayed no clinical signs of disease, which is considered evidence that these bats are a reservoirs species of EBOV. In a 2002 -2003 survey of 1,030 animals including 679 bats from Gabon and the Republic of the Congo, 13 fruit bats were found to contain EBOV RNA (Figure 3).

Mode of transmission

Epidemics of Ebola virus disease are generally through to begin when an individual becomes infected through contact with the meat or body fluids of an infected animal. Once the patient becomes ill or dies, the virus then spreads to others who come into direct contact with the infected individual’s blood, skin or other body fluids. Studies in laboratory primates have found that animals can be infected with Ebola virus through droplet inoculation of virus into the animal mouth or eyes suggesting that human infection can result from the inadvertent transfer of virus to these sites from contaminated hands [22,23].

Person-to-person transmission occurs through direct contact with blood, body fluids, or skin of patients with Ebola virus disease, including those who have died from the infection. Kissing the body is also common. These practices can be extremely dangerous because Ebola victims are often most contagious just after death, when the viral load in their blood is at its highest [10,24].

According to the WHO, the most infectious body fluids are blood, feces, and vomit. Infectious virus has also been detected in urine, semen, saliva, and breast milk [25,26]. Ebola virus can also be spread through direct contact with the skin of patient, but the risk of developing infection from this type of exposure is lower than from exposure to body fluids [27].

A number of studies examining airborne transmission broadly concluded that transmission from pigs to primates could happen without direct contact, because pigs with EVD get very high Ebola virus concentrations in their lungs, and not their bloodstream. Therefore pigs with EVD can spread the disease through droplets in the air or on the ground when they sneeze or cough. By contrast, humans and other primates accumulate the virus throughout their body and specifically in their blood, but not very much in their lungs [2].

Human infection with Ebola virus can occur through contact with wild animals such as hunting, butchering, and preparing meat from infected animals [4].

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Clinical presentation

The incubation period and duration of the disease course of Ebola virus disease varies between 2-21 days with an average of 4-10 days [16].

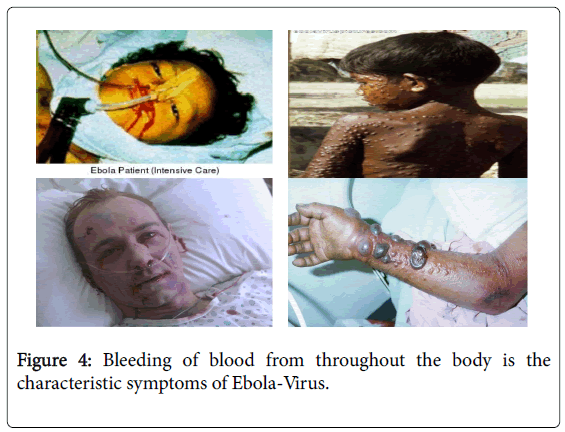

Symptoms

Symptoms usually begin with a sudden flu-like symptoms like quickly on-coming fever, mayopathy, and headache, which are soon followed by bloody vomit and diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, anorexia (loss of appetite), body weakness, abdominal pain, arthralgia (neurologic pain in joints), back pain, mucosal redness of the oral cavity, dysphasia (difficult in swallowing), conjunctivitis, rashes on the body [3]. Some days later, typically begins five to seven days after the first symptoms victims can begin to bleed through the eyes, nose, or mouth. A hemorrhagic rash can develop on the entire body, which also bleeds. Muscle pain and swelling of the pharynx also occur in most victims. The most common signs and symptoms reported from West Africa during the current outbreak from symptom-onset to the time the case was detected include: fever (87%), fatigue (76%), vomiting (68%), diarrhea (66%), and loss of appetite (65%). Unexplained bleeding has been reported from only 18% of patients, most often blood in the stool (about 6%) [13] (Figure 4).

Diagnosis and Differential diagnosis

When Ebola virus disease is suspected in person, his or her travel and work history, along with an exposure to wildlife, are important factors to consider with respect to further diagnostic efforts.

Nonspecific laboratory testing

Possible laboratory indicators of Ebola virus disease include a low platelet count; an initially decreased white blood cell count followed by an increased white blood cell count; elevated levels of the liver enzymes alanine-aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST); and abnormalities in blood clotting often consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) such as a prolonged prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and bleeding time [2].

Specific laboratory testing

The diagnosis of EVD is confirmed by isolating the virus, detecting antibodies against the virus in a person’s blood. Isolating the virus by cell culture, detecting the viral RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and detecting proteins by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are methods best used in early stages of the disease and also for detecting the virus in human remains. Detecting antibodies against the virus is most reliable in later stages of the disease and in those who recover. IgM antibodies are detectable two days after symptom onset and IgG antibodies can be detected 6 to18 days after symptom onset [28] (Table 3).

| Hemoglobin and Hematocrit | Progressive decline(with hemorrhage) |

|---|---|

| White blood cells | Early leucopenia with lymphopenia and subsequent neutrophilia, left shift with atypical lymphocytes, in fatal cases leuocytosis |

| Platelets | Thrombocytopenia |

| Liver-associated enzymes | Highly raised serum aminotransferase (aspartate aminotranferase), hyperproteinaemia |

| Renal functions | Hematuria, proteinuria |

| Coagulations | Prolongation of prothrombine and partial thromboplastin time and fibrin split produce are detectable |

| Other serum chemistry values | Serum amylase concentration may be raised |

Table 3: Most important para clinical findings in the course of Ebola virus disease.

Differential diagnosis

Early symptoms may resemble other tropical infectious diseases like influenza, malaria, typhoid fever, leptospirosis, relapsing fever, anthrax, typhus, non typhoidal salmonellosis, Dengue fever, Chikungunya fever, yellow fever, Lassa fever, Marburg fever, fulminant viral hepatitis, meningococcal septicemia and various forms of encephalitis, which are also prevalent in these countries. Confounding noninfectious syndromes with hemorrhage such as acute leukemia, lupus erythematous, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and hemolytic uremic syndrome also fall into the differential diagnosis [16].

Prevention and Treatment

Prevention

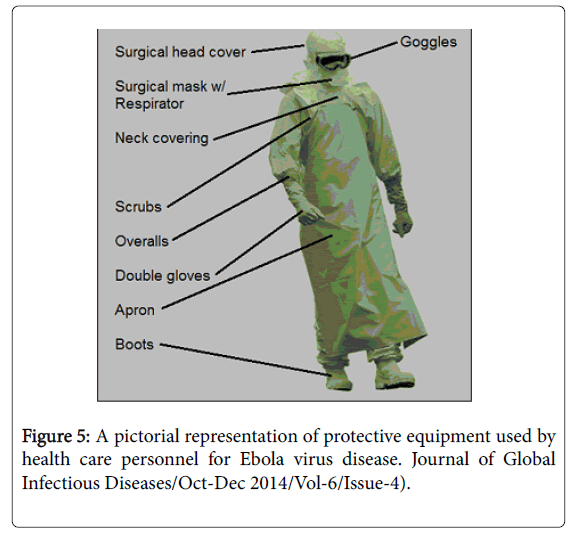

General approach: People who care for those infected with Ebola should wear protective clothing including masks, gloves, gowns and goggles. In 2014, the CDC began recommending that medical personal protective equipment (PPE); in addition, a designated person, appropriately trained in biosafety, should be watching each step of these procedures to ensure they are done correctly [2] (Figure 5).

Several concurrent strategies should be employed to prevent the spread of Ebola virus. Strict infection control measures and the proper use of personal protective equipment are essential to prevent transmission to healthcare workers. In addition, individuals who have been exposed to Ebola virus should be monitored, so that they can be identified quickly if signs and symptoms develop. During the 2014 outbreak, kits were put together to help families treat Ebola disease in their homes, which include protective clothing as well as chlorine powder and other cleaning supplies. Education of those who provide care in these techniques, and the provision of such barrier-separation supplies has been a priority of Doctors without Borders. Ebola virus can be eliminated with heat (heating for 30 to 60 minutes at 60 °C or boiling for 5 minutes). To disinfect surfaces, some lipid solvents such as some alcohol-based products, detergents, sodium-hypochlorite (bleach) or calcium hypochlorite (bleaching powder), and other suitable disinfectants may be used at appropriate concentrations [22,29,30].

Bus meat, an important source of protein in the diet of some Africans, should be handled and prepared with appropriate protective clothing and thoroughly cooked before consumption. If a person with Ebola disease dies, direct contact with the body should be avoided. Certain burial rituals, which may have included making various direct contacts with a dead body, require reformulation such that they consistently maintain a proper protective barrier between the dead body and the laving [31].

Contact tracing is considering important to contain an outbreak. If any of these contacts comes down with the disease, they should be isolated, tested and treated. Then the process is repeated by tracing the contacts’ contacts [32].

Isolation and quarantine: Isolation refers to separating those who are sick from those who are not. Quarantine refers to separating those who may have been exposed to a disease until they either show signs of the disease or are no longer at risk. In the United States, the law allows quarantine of those infected with Ebola virus. During the 2014 Ebola disease outbreak, Liberia closed schools [33,34].

Environmental infection control: If a patient with suspected or confirmed Ebola virus disease is being cared for in a healthcare setting, specific precautions should be taken to reduce the potential risk of virus transmission through contact with contaminated surfaces. The CDC has provided specific recommendations for environmental infection control in hospitals, general healthcare settings in West Africa, and provides information about restrictions on travel and transport of asymptomatic persons who have been exposed to Ebola virus. Asymptomatic persons who have had a possible exposure at any risk level should be monitored for signs and symptoms of Ebola virus disease. Monitoring should continue for 21 days after the last known exposure; the development of fever and/or other clinical manifestations suggestive of Ebola virus disease should be reported immediately [22].

Breastfeeding and infant care: Ebola virus can be transmitted by close contact of an infected mother with her children. Thus, the CDC recommends that mothers with Ebola virus disease avoid close contact with their infants if the infant can receive adequate care and nutrition in other ways [35,36].

Precautions during the convalescent period: Patients recovering from Ebola virus disease may continue to have virus present in certain body fluids (e.g. urine, semen, vaginal secretions, and breast-milk) even if virus is no longer detectable in the blood. However, the risk of transmission secondary to virus in these sites remains unclear. To prevent sexual transmission of Ebola through semen, the WHO recommends that men abstain from sex (including oral sex) for three months after onset of symptoms, or use condoms if abstinence is not possible. There are currently no recommendations to guide when infected women can resume sexual activity and/or breast feeding [37].

Pregnancy

The CDC and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology have issued recommendations for the care of pregnant women with Ebola virus disease. Strict infection control precautions must be used when caring for all pregnant patients with Ebola virus disease. Case reports suggest that there is a high risk for fetal death and pregnancyassociated hemorrhage. However, there are no data to suggest whether cesarean or vaginal delivery is preferred or when the baby should be delivered [38].

Vaccines

Due to the pathogencity of the virus, no conventional vaccines consisting of inactivated/killed virus, or made from an attenuated viral strain, are being developed for Ebola because of the risk of incomplete inactivation of the virus or of reversion to a fully active form. Instead, these vaccines are based on relatively new approaches that have been made possible with the advancement of molecular biology and recombinant genetic technologies introduced during the last 10-20 years. Clinical trials for several candidate vaccines are in various phases and a safe and effective vaccine is hoped for by the end of 2015. Currently, two vaccine candidates are entering efficacy trials in humans [39,40].

The first is cAd3-ZEBOV developed by GlaxoSmithKline and tested by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). The second is the rVSV tested by the New Link Genetics Corporation after being licensed from the Public Health Agency of Canada. Both vaccines demonstrated promising rates of efficacy in nonhuman primates, but the translation of these results to human subjects has not yet been accomplished [40,41].

Treatment

Approach to therapy

There are no approved treatments available for EVD. Clinical management should focus on supportive care of complications, such as hypovolemia, electrolyte abnormalities, hematologic abnormalities, refractory shock, hypoxia, hemorrhage, septic shock, multi-organ failure. The mainstay of treatment for Ebola virus disease involves supportive care to maintain adequate cardiovascular function while the immune system mobilizes an adaptive response to eliminate the infection. In addition, several experimental antiviral therapies have been used in patients with Ebola virus disease during the 2014 outbreak in West Africa. The efficacy of these agents is unclear and is an active area of investigation. In addition, the availability of these drugs is limited [13,17].

Antiviral therapy

There are no approved medications for the treatment of Ebola virus disease or for post-exposure prophylaxis in persons who have been exposed to the virus but have not yet become ill. There is urgent need for evaluation of several experimental therapies that had been developed specifically to treat or prevent Ebola or Marburg virus infection, but have only been tested in laboratory animals. In addition, there is renewed interest in the potential value of convalescent plasma and whole blood transfusions from Ebola survivors. Although experimental treatments for Ebola virus infection are under development, they have not yet been fully tested for safety or effectiveness [42].

Non-clinical and clinical data made available for:

• Three nucleoside polymerase inhibitors: BCX4430, brincidofovir, and favipiravir;

• Two oligonucleotide based products: TKM-100802 and AVI-7537;

• A cocktail of monoclonal antibodies: ZMapp

Competing Interests

The Authors’ declare that there are no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

FAG has made substantial contributions to conception and gathering of information and has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and has given final approval of the version to be published. MFS has made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. BKG has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors’ are grateful to all the health care professionals, researchers and governments working to prevent this global terror risking their life, family and community. We are also grateful to all the information resources included in this review article with.

References

- Shears P (2015). Ebola Virus Disease in Africa: Epidemiology and Health Facility related Transmission: Department of Infection Control Wirral University Hospital, UK; 90:1-9.

- Thippeswamy NB (2015) Ebola Virus Disease: New Horizons in Biotechnology. India, P 007-014.

- Karunakar T, Kumar E, Naresh K, Sriram R (2013) A review on Ebola virus, Inter J of Pharmacotherapy 3(2): 55-59.

- Krejcova L, Michaleket P, Chudobova D, Heger Z, Hynek D, et al. (2015) West Africa Ebola Outbreak 2014, Journal of Metallomics and Nanotechnologies 1: 6-12.

- World Health Organization. (2014). "The first cases of Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa".

- Gostin LO, Friedman EA (2015) A retrospective and prospective analysis of the west African Ebola virus disease epidemic: robust national health systems at the foundation and an empowered WHO at the apex. Lancet 385: 1902-1909.

- Peters CJ, LeDuc JW (1999) An introduction to Ebola: the virus and the disease.J Infect Dis 179 Suppl 1: ix-xvi.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) Interim guidance for environmental infection control in hospital for Ebola.

- Norheim G, Oftung F (2014) Vaccine-based mitigation of the 2014 Ebola Viral Disease (EVD) epidemic: Gap analysis and proposal for Norwegian initiatives.

- James J, Charlotte F, Daniel K, Carafano J (2015) The Ebola Outbreak of 2013-2014: An Assessment of U.S. Actions. Special report, No.166.

- Green A (2014) Ebola emergency meeting establishes new control centre.Lancet 384: 118.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) Review of Human to Human transmission of Ebola virus.

- Woldu, AM, Lenjisa LJ, Tegegne TG, Satessa GD (2014) Emerging Therapeutic Approaches to Combat the Pandemicity of the Deadly Ebola Virus. American Journal of Phytomedicine and Clinical Therapeutics. ISSN 2321-27483.

- Castillo M (2012) "Ebola virus claims 31 lives in Democratic Republic of the Congo". United States: CBS News.

- World Health Organization (2015) The Ebola outbreak in Liberia is over.

- Bagherani N, Smoller BR, Kannangara AP, Gianfaldoni S, Wang X, et al. (2015) An Overview on Ebola. Department of Dermatology, University of Rome, Italy, Volume 2: 64-73.

- Sarathi K, Stanislaw P, Stawicki (2014) The Emergence of Ebola as a Global Health Security Threat: From “Lessons Learned†to Coordinated Multilateral Containment Efforts, J Glob Infect Dis6:164-77

- Chertow DS, Kleine C, Edwards JK, Scaini R, Giuliani R, et al. (2014) Ebola virus disease in West Africa--clinical manifestations and management.N Engl J Med 371: 2054-2057.

- Lyon GM, Mehta AK, Varkey JB, Brantly K, Plyler L, et al. (2014) Clinical care of two patients with Ebola virus disease in the United States.N Engl J Med 371: 2402-2409.

- Bray M, Geisbert TW (2005) Ebola virus: the role of macrophages and dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever.Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37: 1560-1566.

- Basler CF (2005) Interferon antagonists encoded by emerging RNA viruses. Modulation of Host Gene Expression and Innate Immunity by viruses. Palese p (ED), Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands 197.

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute (2014) Ebola viral disease interim Guideline, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 1-83

- Weingartl HM, Nfon C, Kobinger G (2013) Review of Ebola virus infections in domestic animals.DevBiol (Basel) 135: 211-218.

- Bausch DG, Towner JS, Dowell SF, Kaducu F, Lukwiya M, et al. (2007) Assessment of the risk of Ebola virus transmission from bodily fluids and fomites.J Infect Dis 196 Suppl 2: S142-147.

- Kreuels B, Wichmann D, Emmerich P, Schmidt-Chanasit J, de Heer G, et al. (2014) A case of severe Ebola virus infection complicated by gram-negative septicemia.N Engl J Med 371: 2394-2401.

- Towner JS, Rollin PE, Bausch DG, Sanchez A, Crary SM, et al. (2004) Rapid diagnosis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever by reverse transcription-PCR in an outbreak setting and assessment of patient viral load as a predictor of outcome.J Virol 78: 4330-4341.

- Dowell SF, Mukunu R, Ksiazek TG, Khan AS, Rollin PE, et al. (1999) Transmission of Ebola hemorrhagic fever; a study of risk factors in family members, Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo,1995.Commission de Luttecontre les Epidemies a kikwit. Infect Dis 179 Suppl 1:S87.

- Goeijenbier M, van Kampen JJ, Reusken CB, Koopmans MP, van Gorp EC (2014) Ebola virus disease: a review on epidemiology, symptoms, treatment and pathogenesis.Neth J Med 72: 442-448.

- Peters CJ (1998) Hemorrhagic Fevers in the African Health Care Setting. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Infect Dis

- Baron RC, McCormick JB, Zubeir OA (1983) Ebola virus disease in southern Sudan: hospital dissemination and intrafamilial spread.Bull World Health Organ 61: 997-1003.

- Centers for Disease Control and prevention and World Health Organization (1998) Infection control for viral hemorrhagic Fevers in the Africa Health Care setting.

- Centers for Disease Control. gov. (2014) “About Quarantine and Isolationâ€.

- Lewis D (2014) “Liberia shuts schools, considers quarantine to curb Ebolaâ€. Reuters.

- Kortepeter MG, Bausch DG, Bray M (2011) Basic clinical and laboratory features of filoviral hemorrhagic fever.J Infect Dis 204 Suppl 3: S810-816.

- Centers for Disease Control (2014) “Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Preventionâ€

- Kilmarx PH, Clarke KR, Dietz PM, Hamel MJ, Husain F, et al. (2014) Ebola virus disease in health care workers--Sierra Leone, 2014.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63: 1168-1171.

- Jamieson DJ, Uyeki TM, Callaghan WM, Meaney-Delman D, Rasmussen SA (2014) What obstetrician-gynecologists should know about Ebola: a perspective from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.ObstetGynecol 124: 1005-1010.

- Jocelyn Y (2014). Antiviral InteliStrat in the 2014 Ebola Virus Outbreak in West Africa: Current Perspectives for Prevention and Treatment, Journal of Human Virology &Retrovirology1:4.

- Hampton T (2014) Largest-ever outbreak of Ebola virus disease thrusts experimental therapies, vaccines into spotlight.JAMA 312: 987-989.

- Cheepsattayakorn A, Cheepsattayakorn R (2015) Ebola Virus Disease: Updated Path physiology and Clinical Aspects. Ann ClinPathol 3: 1048.

- West TE (2014) Clinical Presentation and Management of Severe Ebola Virus Disease, Ann Am ThoracSoc 11:1341-50.

Citation: Gebretadik FA, Seifu MF, Gelaw BK (2015) Review on Ebola Virus Disease: Its Outbreak and Current Status. Epidemiology (sunnyvale) 5:204. DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000204

Copyright: ©2015 Gebretadik FA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 21235

- [From(publication date): 12-2015 - Mar 31, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 19608

- PDF downloads: 1627