Review Article Open Access

Reduction in Acquisitive Crime During a Heroin-Assisted Treatment: a Post-Hoc Study

Demaret I1,2*, Deblire C1,2, Litran G1,2, Magoga C1,2, Quertemont E3, Ansseau M2 and Lemaitre A11Institute for Human and Social Sciences, University of Liège, 4000, Belgium

2Department of Psychiatry, University of Liège, 4000, Belgium

3Department of Psychology, Cognition and Behaviour, University of Liège, 4000, Belgium

- Corresponding Author:

- Isabelle Demaret

Institute for Human and Social Sciences

Boulevard du Rectorat 3 (B31) at 4000 Liège, Belgium

Tel: 003243663158

E-mail: isabelle.demaret@ulg.ac.be

Received date: February 13, 2015; Accepted date: February 18, 2015; Published date: February 25, 2015

Citation: Demaret I, Deblire C, Litran G, Magoga C, Quertemont E, et al. (2015) Reduction in Acquisitive Crime During a Heroin-Assisted Treatment: a Post-Hoc Study. J Addict Res Ther 6:208. doi:10.4172/2155-6105.1000208

Copyright: © 2015 Demaret I, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy

Abstract

Background: We investigated the evolution of the criminal involvement of severe heroin addicts recruited in a randomised controlled trial comparing heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) to methadone treatment.

Method: During the trial, detailed questions were asked on crimes committed and experienced at baseline and every 3 months during 12 months. We analysed our data in a post-hoc study.

Results: Severe heroin addicts included in the trial showed a high level of criminal involvement in the past but their involvement had decreased at baseline. At the 12-month assessment, crimes committed and experienced decreased significantly in both groups but the difference between the groups was not significant.

Conclusion: A new opioid maintenance treatment, with methadone or diacetylmorphine, can help severe heroin users to decrease their criminal involvement.

Keywords

Heroin-assisted treatment; Diacetylmorphine; Methadone; Criminal involvement

Introduction

Drug and crime are frequently associated in case of regular use of illicit drug [1,2]. The association is especially strong between expensive drugs use, as heroin or cocaine, and acquisitive crime, as selling illicit drugs, prostitution, shoplifting and other thefts [3-5]. However, there is no definite causal link: each heroin user is not delinquent and crimes can precede or follow the first use of illicit drug [1,3,6].

Opioid maintenance treatment can help heroin addicts to reduce crimes intended to acquire income for heroin use [2,7]. If methadone treatment can help most of the street heroin addicts [8,9], for severe heroin users pursuing street heroin use while in Methadone Treatment (MT), Heroin-Assisted Treatment (HAT) is another solution [10]. Patients in HAT showed also a reduction of crimes [5,11-14].

As in other countries, heroin addiction remains a critical problem in Belgium in some urban areas. In 2007, among the 200.000 inhabitants of the commune of Liège more than 1% of the inhabitants aged from 15 to 64 were addicted to heroin [15]. Following the example of other experiments conducted in Europe [13,14,16-18] and in Canada [19], a trial comparing HAT to existing MT was conducted in Belgium. The result of the study was present elsewhere [20]. We focused our present post-hoc analysis on the evolution of the criminal involvement of the 74 heroin addicts included in the trial.

Methods

Ethics

The Ethics Committee of the University of Liège approved this trial on March 16, 2010. It was registered in the European database of all clinical trials with the Eudra CT number 2010-019026-13. The trial was accepted by the National Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products on May 7, 2010. Each participant signed the informed consent form approved by the Ethics committee.

Trial design

TADAM, a Treatment Assisted by Diacetylmorphine (DAM) was a randomised controlled trial comparing HAT with MT during 12 months. Between January 17, 2011 and January 16, 2012, 74 participants were included in the trial: 36 participants were randomised in the experimental group and 38 in the control group. The detailed method of the trial has been already described in details [20].

Assessments

The research team assessed participants on their criminal involvement with the Europe ASI and questions on crimes, committed or experienced. Illicit drug users are also frequent victims of thefts or assaults [3]. 13 questions concerned illegal acts committed: different forms of thefts (as shop-lifting and burglary), fencing, forgery/fraud, prostitution, selling illicit drugs and assaults (including homicide). 5 questions concerned victimisation: thefts, assaults, sexual abuse and being deceived while buying illicit drugs. For each participant, we compared criminal proceedings recorded by the public prosecutor’s department to self-reported crimes during the same period. Our analysis was mainly based upon self-reported data as drug users generally report more criminal acts than are prosecuted [21]. Prosecutions were used to verify the self-reported. If more acts were prosecuted than self-reported during the previous month, we registered the number of prosecutions.

The researchers, independent from the treating staff, assessed participants at baseline at the policlinic of the Liège University Hospital. After baseline, participants treated by DAM where assessed in the HAT centre and other participants were invited at the policlinic or, when necessary, were interviewed in prison or in their residential treatment centre. At each assessment, participants who were not (or were no more) in HAT received between 15 and 60 euro (depending on the presence of medical examination, blood and urine sample). At 12 months, the research team assessed 70 participants (35 in each group).

Results

Participant characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were found between the groups. The retention rate in the allocated treatment centre was higher for the experimental group: 27 (74%) versus 13 (34%). The difference was statistically significant (p=0.00052) but this retention rate did not take into account participants treated in MT outside of their allocated centre or abstinent. Including all participants in opioid maintenance treatment or voluntarily abstinent at the 12-month assessment, the difference between the groups was no more significant: 30 (83%) remained in the experimental group (27 in HAT, 2 in MT and 1 abstinent) and 30 (79%) in the control group (all in MT).

| Baseline characteristicsa | n = 74 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |

| Male sex | 65 (88%) |

| Age – years | 43 [7] |

| Belgian | 62 (84%) |

| Employed during previous month | 2 (3%) |

| Social or medical welfare as main source of income | 58 (78%) |

| No stable housing in past month | 21 (28%) |

| Criminal involvement ("during life) | |

| Ever convicted | 72 (97%) |

| Ever condemned | 56 (76%) |

| Ever incarcerated | 47 (64%) |

| Criminal involvementb | 74 (100%) |

| Illegal activitiesb | 72 (97%) |

| - Assaults | 29 (39%) |

| - Acquisitive crimes (thefts, selling illicit drugs, forgery/fraud, fencing or prostitution) | 72 (97%) |

| Victimisationb | 72 (97%) |

| - Assaults and sexual abuse | 47 (64%) |

| - Acquisitive crimes (thefts or deceit while dealing) | 72 (97%) |

| Drug use | |

| Regular street heroin use – years | 20 [7] |

| Street heroin in past month – days | 27 [5] |

| Cocaine in past monthb | 34 (46%) |

| Ever injected | 60 (81%) |

| Habitual use of street heroin through injection | 12 (16%) |

| Previous addiction treatment | |

| Regular methadone use – years | 14 [7] |

| Number of previous drug treatments | 9 [13] |

aData are number of participants (%) or mean [s.d.]

dSelf-reported data complemented with toxicological analysis or registered criminal

proceedings

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the 74 participants randomised in TADAM trial.

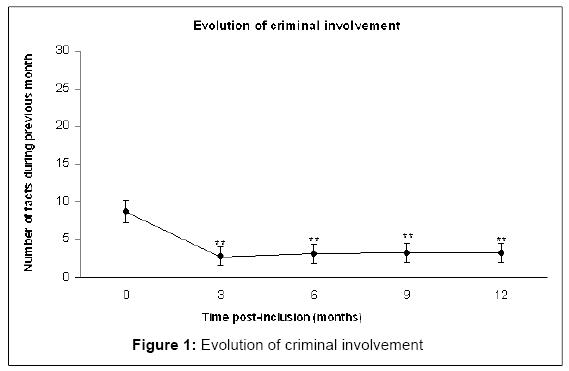

Among participants criminally involved during the month before baseline (24 in the experimental group versus 23 in the control group), participants who reduced their criminal involvement after 12 months were more numerous in the experimental group (n=20; 83% versus n=17; 74%). The difference between the groups was higher if we included only participants who showed improvement after 12 months: 17 (71%) decreased criminal acts in the experimental group versus 11 (52%) in the control group. However, as shown by our main analysis (Figure 1 and Table 1), no significant main effect of the group was noticed [F(1.62)=1.46; p=0.23] and no significant interaction [F(4.248)=1.56; p=0.19], but both groups significantly reduced their criminal involvement as indicated by a significant main effect of time post-inclusion [F(4.248)=8.96; p<0.001](20).

Between baseline and the 12-month assessment, the mean number of crimes during the last month decreased by 65% for all participants but crimes by perpetrator decreased only by 33% (Table 2). Participants committed mainly the same type of crimes: during the 6 previous months, each perpetrator committed on average 1.5 different types of crimes at baseline and 1.2 at the 12-month assessment. During the previous month, the average was 1.4 types of crimes at baseline and 1.0 at the 12-month assessment. At the 12-month assessments, no perpetrator reported more than 2 different types of crimes.

| Criminal involvement during 6 previous months | Baseline | 12-month assessment | |||||||||||

| Perpetrators / Victims | % (N=74) | Crimes | Crimes by participants (N=74) | Crimes by perpetrators / victims | Perpetrators / Victims | % (N=70) | Crimes | Crimes by participants (N=70) | Crimes by perpetrators / victims | ||||

| Criminal involvement | 63 | 85% | 3 618 | 48.9 | 57.4 | 40 | 57% | 812 | 11.6 | 20.3 | |||

| Illegal activities | 47 | 64% | 3 331 | 45.0 | 70.9 | 29 | 41% | 736 | 10.5 | 25.4 | |||

| - Assaults | 4 | 5% | 18 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 6 | 9% | 21 | 0.3 | 3.5 | |||

| - Acquisitive crimes | 46 | 62% | 3 313 | 44.8 | 72.0 | 27 | 39% | 715 | 10.2 | 26.5 | |||

| -- thefts | 28 | 38% | 826 | 11.2 | 29.5 | 14 | 20% | 117 | 1.7 | 8.4 | |||

| -- selling illicit drugs | 25 | 34% | 2 012 | 27.2 | 80.5 | 10 | 14% | 342 | 4.9 | 34.2 | |||

| -- forgery/fraud, fencing | 8 | 11% | 223 | 3.0 | 27.9 | 3 | 4% | 4 | 0.1 | 1.3 | |||

| -- prostitution | 2 | 3% | 252 | 3.4 | 126.0 | 2 | 3% | 252 | 3.4 | 126.0 | |||

| Victimisation | 42 | 57% | 287 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 25 | 36% | 76 | 1.1 | 3.0 | |||

| - Assaults | 6 | 8% | 11 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 5 | 7% | 5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | |||

| - Acquisitive crimes | 41 | 55% | 276 | 3.7 | 6.7 | 24 | 34% | 71 | 1.0 | 3.0 | |||

| -- thefts | 24 | 32% | 154 | 2.1 | 6.4 | 17 | 24% | 27 | 0.4 | 1.6 | |||

| -- deceived while buying drugs | 28 | 38% | 122 | 1.6 | 4.4 | 14 | 20% | 44 | 0.6 | 3.1 | |||

| Criminal involvement during 30 previous days | Baseline | 12-month assessment | |||||||||||

| Perpetrators / Victims | % (N=74) | Crimes | Crimes by participants (N=74) | Crimes by perpetrators / victims | Perpetrators / Victims | % (N=70) | Crimes | Crimes by participants (N=70) | Crimes by perpetrators / victims | ||||

| Criminal involvement | 47 | 64% | 638 | 8.6 | 13.6 | 22 | 31% | 223 | 3.2 | 10.1 | |||

| Illegal activities | 37 | 50% | 585 | 7.9 | 15.8 | 16 | 23% | 194 | 2.8 | 12.1 | |||

| - Assaults | 3 | 4% | 8 | 0.1 | 2.7 | 3 | 4% | 6 | 0.1 | 2.0 | |||

| - Acquisitive crimes | 37 | 50% | 577 | 7.8 | 15.6 | 14 | 20% | 191 | 2.7 | 13.6 | |||

| -- thefts | 19 | 26% | 173 | 2.3 | 9.1 | 5 | 7% | 66 | 0.9 | 13.2 | |||

| -- selling illicit drugs | 22 | 30% | 334 | 4.5 | 15.2 | 6 | 9% | 111 | 1.6 | 18.5 | |||

| -- forgery/fraud, fencing | 5 | 7% | 28 | 0.4 | 5.6 | 2 | 3% | 2 | 0.0 | 1.0 | |||

| -- prostitution | 2 | 3% | 42 | 0.6 | 21.0 | 1 | 1% | 12 | 0.2 | 12.0 | |||

| Victimisation | 22 | 30% | 53 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 9 | 13% | 26 | 0.4 | 2.9 | |||

| - Assaults | 1 | 1% | 3 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| - Acquisitive crimes | 22 | 30% | 50 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 9 | 13% | 26 | 0.4 | 2.9 | |||

| -- thefts | 10 | 14% | 23 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 5 | 7% | 5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | |||

| -- deceived while buying drugs | 15 | 20% | 27 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 5 | 7% | 21 | 0.3 | 4.2 | |||

Table 2: Details of criminal involvement before baseline and before the last assessment.

Discussion

Compared to participants in other trials[13,14,16-19,22], our participants showed the same level of criminal involvement in the past but were less involved in illegal activities at baseline (Table 3). The main crimes committed by our population were acquisitive crime. This lower rate of delinquency at baseline in our trial could be related to the higher rate of social assistance welfare in our population (78%).

| Demaret et al., 2014 | Perneger et al., 1998 | van den Brink et al., 2003 | March et al., 2006 | Haasen et al., 2007 | Oviedo-Joekes et al., 2009 | Strang et al., 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of beginning of recruitment | 2011 | 1995 | 1998 | 2003 | 2002 | 2005 | 2005 |

| Number of participants | 74 | 51 | 549 | 62 | 1015 | 251 | 127 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age | 43 | 32 | 39 | 37 | 36 | 40 | 37 |

| Men | 88% | 75% | 80% | 90% | 80% | 61% | 73% |

| Employment | 3% | - | 8% | 5% | - | 16% | 2% |

| Social or medical assistance | 78% | 46% | 58% | - | 49% | 36% | - |

| Unstable housing | 28% | - | 13%2 | 21%3 | 31%4 | 73%5 | - |

| Criminological data | |||||||

| Illegal incomes as main source of income during previous month | 11% | - | 27% | - | 23% | - | - |

| Illegal activities during previous month | 50%6 | - | - | - | 73% | 74%6 | - |

| Ever convicted | 93% | - | - | - | 96% | 94% | - |

| Ever incarcerated | 64% | - | 82% | - | 75% | - | 73% |

| Drug use and treatment | |||||||

| Life time drug use | |||||||

| Heroine | 20 | - | 16 | 20 | 14 | 14 | 16 |

| Methadone | 14 | - | 12 | - | - | - | - |

1 Any hepatitis

2 Stable housing = 87%

3 Homeless

4 Stable housing situation = 70%

5 Homeless or living in shelter or hotel room

Table 3: Comparison with other heroin-assisted treatment trials.

Participants of both group decreased significantly their criminal involvement during the project. The number of perpetrators decreased more in the experimental group but the difference between the groups was not significant. Other trials found a significantly greater reduction of crimes in the group treated with HAT than in the group treated with MT [5,13,14,17]. The reduction could be a consequence of less street heroin use and detachment from the drug scene [5].

A few number of perpetrators committed a lot of crimes in each groups: at the 12-month assessment, the 253 prostitution crimes committed during the previous 6 months were reported by only 2 women (in the experimental group). On the same period, 1 participant in the experimental group reported 180 acts of selling illicit drugs and 8 participants in the methadone group reported 156 acts of selling illicit drugs. This configuration (few perpetrators and many acts by perpetrators) had two consequences: first, to find a difference between the groups, a greater number of perpetrators is necessary and, second, the great proportion of acts by perpetrator indicate a specialisation of some participants. Another evidence for this specialisation is that each perpetrator reported at the last assessment in average 1.0 type of fact during the previous months.

Although 93% of the participants reported a delinquent past, 36% did not report any offence during the 6 months before baseline and were not prosecuted. The association between drug dependence and criminality is not ineluctable even for severe heroin users.

Strengths and limits

The absence of statistically significant difference between both groups in our trial could be related to the small number of perpetrators at baseline (47 during the previous 6 months and 37 during the previous month) combined to the high number of acts committed by each perpetrator. With a small number of participants, as in our trial, prevalence is more sensible to changes than incidence. However, on a societal point of view, the total number of crimes committed has more consequences than the number of delinquents.

Participants could have underreported the number of their criminal activities to give a more socially desirable response, but, even in this case, self-reported data are more sensible than registered prosecutions [21].

35 participants reported illegal activities during the previous month in response to one general question in the Europe ASI, but 2 more participants reported crimes during the same period according to the 13 questions of our delinquency questionnaire. Detailed questions about crimes enable participants to remember better what they did than a general question [23].

Conclusion

Acquisitive crime linked to heroin use can be reduced by an opioid maintenance treatment as HAT. However, even a new methadone treatment for severe heroin users can also help patients to decrease their criminal behaviour related to street heroin use.

Acknowledgements

The TADAM trial was funded at 80% by the Federal Minister of Social Affairs and Public Health. It was also funded by the City and the University of Liège. Only the perpetrators were involved in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data as in the writing of this paper.

We thank each participant of the TADAM trial; the staff from the HAT centre and from the partner centres; the staff of the University of Liège who always helped us quickly to solve administrative problems; the public prosecutor’s office who let us examine the prosecution records of our participants; the staff of the policlinic of the Liège University Hospital, especially the nurses; the experts of our Scientific committee; the researchers from other countries who gave us information and helped us to visit their HAT centres; the staff from these centres; the Psychiatric Platform of Liège who invited us to the meetings of the addiction network of the Province of Liège; the founders of the trial and the Drug Cell of the Federal Public Service of Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment who were in charge of the administrative follow up of the TADAM assessment.

References

- Coid J, Carvel A,Kittler Z, Healey A, Henderson J (2000) Opiates, criminal behaviour and methadone treatment. Home Office, London 116.

- Gossop M,Trakada K, Stewart D,Witton J (2005) Reductions in criminal convictions after addiction treatment: 5-year follow-up. Drug Alcohol Depend 79: 295-302.

- Ansseau M (2005) DHCoDalivranced'haroAne sous contralemedical: Etude de faisabilityet de suivi. Academia press,Gand,Belgique.

- Lasnier B,Brochu S, Boyd N, Fischer B (2010) A heroin prescription trial: case studies from Montreal and Vancouver on crime and disorder in the surrounding neighbourhoods. Int J Drug Policy 21: 28-35.

- Löbmann R,Verthein U (2009) Explaining the effectiveness of heroin-assisted treatment on crime reductions. Law Hum Behav 33: 83-95.

- Brochu S (2005) Drogue etcriminalita: une relation complexe. Presses de University de Montreal,Montreal.

- BuktenA,Skurtveit S,Gossop M, Waal H,Stangeland P, et al. (2012) Engagement with opioid maintenance treatment and reductions in crime: a longitudinal national cohort study. Addiction 107: 393-399.

- Amato L,Davoli M,Perucci CA,Ferri M,Faggiano F, et al. (2005) An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. J SubstAbuse Treat 28: 321-329.

- Mattick RP,Kimber J, Breen C,Davoli M (2008) Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev:CD002207.

- Ferri M,Davoli M,Perucci CA (2011) Heroin maintenance for chronic heroin-dependent individuals. Cochrane Database SystRev : CD003410.

- Killias M,Aebi MF,Ribeaud D,Rabasa J (2002) Rapport final sur les effets de la prescription de stupAfiantssur ladAlinquance des toxicomanes. UniversitA de Lausanne, Lausanne.

- Killias M,Aebi M,&Ribeaud D (1998) Effects of heroin prescription on police contacts among drug-addicts. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Reserach 6:433-438.

- Perneger TV,Giner F,del Rio M, Mino A (1998) Randomised trial of heroin maintenance programme for addicts who fail in conventional drug treatments. BMJ 317: 13-18.

- van den Brink W,Hendriks VM,Blanken P,Koeter MW, van Zwieten BJ, et al. (2003) Medical prescription of heroin to treatment resistant heroin addicts: two randomised controlled trials. BMJ 327: 310.

- Demaret I,HernA P,LemaitreA,Ansseau M (2011) Feasibility assessment of heroin-assisted treatment in Liage, Belgium. ActaPsychiatricaBelgica 111:3-8.

- Haasen C,Verthein U,Degkwitz P, Berger J,Krausz M, et al. (2007) Heroin-assisted treatment for opioid dependence: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 191: 55-62.

- March JC, Oviedo-Joekes E,Perea-Milla E, Carrasco F; PEPSA team (2006) Controlled trial of prescribed heroin in the treatment of opioid addiction. J SubstAbuse Treat 31: 203-211.

- Strang J,Metrebian N,Lintzeris N, Potts L,Carnwath T, et al. (2010) Supervised injectable heroin or injectable methadone versus optimised oral methadone as treatment for chronic heroin addicts in England after persistent failure in orthodox treatment (RIOTT): a randomised trial. Lancet 375: 1885-1895.

- Oviedo-Joekes E,Brissette S, Marsh DC,Lauzon P,Guh D, et al. (2009) Diacetylmorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction. N Engl J Med 361: 777-786.

- Demaret I (2014) Efficacy of heroin-assisted treatment in Belgium: a randomised controlled trial. EurAddict Res In press.

- Darke S1 (1998) Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend 51: 253-263.

- Oviedo-Joekes E,Nosyk B,Brissette S,Chettiar J,Schneeberger P, et al. (2008) The North American Opiate Medication Initiative (NAOMI): profile of participants in North America's first trial of heroin-assisted treatment. J Urban Health 85: 812-825.

- van der Zanden BP,Dijkgraaf MG,Blanken P, van Ree JM, van den Brink W (2007) Patterns of acquisitive crime during methadone maintenance treatment among patients eligible for heroin assisted treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend 86: 84-90.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction Recovery

- Alcohol Addiction Treatment

- Alcohol Rehabilitation

- Amphetamine Addiction

- Amphetamine-Related Disorders

- Cocaine Addiction

- Cocaine-Related Disorders

- Computer Addiction Research

- Drug Addiction Treatment

- Drug Rehabilitation

- Facts About Alcoholism

- Food Addiction Research

- Heroin Addiction Treatment

- Holistic Addiction Treatment

- Hospital-Addiction Syndrome

- Morphine Addiction

- Munchausen Syndrome

- Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

- Nutritional Suitability

- Opioid-Related Disorders

- Relapse prevention

- Substance-Related Disorders

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 13877

- [From(publication date):

March-2015 - Nov 21, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9517

- PDF downloads : 4360